Khalji dynasty

| Khalji Sultanate | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1290–1320 | |||||||||||

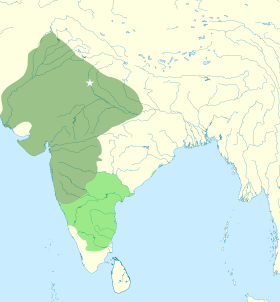

Territory controlled by the Khaljis (dark green) and their tributaries (light green) | |||||||||||

| Capital | Delhi | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (official)[1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||

• 1290–1296 | Jalal ud din Firuz Khalji | ||||||||||

• 1296–1316 | Alauddin Khalji | ||||||||||

• 1316 | Shihab ad-Din Umar | ||||||||||

• 1316–1320 | Qutb ad-Din Mubarak | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1290 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1320 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||

The Khalji or Khilji[lower-alpha 1] dynasty was a Muslim dynasty which ruled large parts of the Indian subcontinent between 1290 and 1320.[2][3][4] It was founded by Jalal ud din Firuz Khalji and became the second dynasty to rule the Delhi Sultanate of India. The dynasty is known for their faithlessness and ferocity, conquests into the Hindu south,[2] and for successfully fending off the repeated Mongol invasions of India.[5][6]

Origins

The Khaljis were of Turko-Afghan origin:[7] a Turkic people that had settled in Afghanistan before moving to Delhi.[8] The ancestors of Jalaluddin Khalji had lived in the Helmand and Lamghan regions for over 200 years.[9]

There is some debate about the ethnic group that the Khaljis belonged to, when the dynasty ruled. The Khalaj people in western Iran speak the Khalaj language,[10] The modern Pashto-speaking Ghilzai Afghans are also descendants of Khalaj people; their transformation into an ethnic Afghan group can be dated to earlier than the 16th century. After a number of ethnic transformations, the Afghan Khalaj became the Ghilzay tribe of Afghans.[11] Between the 10th and 13th centuries, some sources refer to the Khalaj people as of Turkic, but some others do not.[12] Ibn Khordadbeh (9th century) mentions the Khalaj people while describing the "land of the Turks". But the distance between the Amu Darya and the Talas is such as it would have been impossible for the tribes living beyond the Amu Darya to use the Talas pastures as winter quarters, leading to the conclusion that the text has been corrupted somehow or that some Khalaj still lived near the Khallukh at the time. Minorsky argues that the early history of the Khalaj tribe is obscure and adds that the identity of the name Khalaj is still to be proved.[13] Mahmud al-Kashgari (11th century) does not include the Khalaj among the Oghuz Turkic tribes, but includes them among the Oghuz-Turkman (where Turkman meant "Like the Turks") tribes. Kashgari felt the Khalaj did not belong to the original stock of Turkish tribes but had associated with them and therefore, in language and dress, often appeared "like Turks".[12] The 11th century Tarikh-i Sistan and the Firdausi's Shahnameh also distinguish and differentiate the Khalaj from the Turks.[14] Minhaj-i-Siraj Juzjani (13th century) never identified Khalaj as Turks, but was careful not to refer to them as Afghans. They were always a category apart from Turks, Tajiks and Afghans.[12] Muhammad ibn Najib Bakran's Jahan-nama explicitly describes them as Turkic,[15] although he notes that that their complexion had become darker (compared to the Turks) and their language had undergone enough alterations to become a distinct dialect. The modern historian Irfan Habib has argued that the Khaljis were not related to the Turkic people and were instead ethnic Afghans. Habib pointed out that, in some 15th century Devanagari Sati inscriptions, the later Khaljis of Malwa have been referred to as "Khalchi" and "Khilchi", and that the 17th century chronicle Padshahnama, an area near Boost in Afghanistan (where the Khalaj once resided) as "Khalich". Habib theorizes that the earlier Persian chroniclers misread the name "Khalchi" as "Khalji", but this is unlikely, as this would mean that every Persian chronicler writing between the 13th and 17th centuries made the same mistake. Habib also argues that no 13th century source refers to the Turkish background of the Khaljis, but this assertion is wrong, as Muhammad ibn Najib Bakran's Jahan-nama explicitly describes the Khalaj people as Turkic.[15]

The accounts describing the Khaljis' rise to power in India indicate that they were regarded as a race quite distinct from the Turks in late 13th century Delhi.[16] Over the centuries, the Khaljis had intermarried with the local Afghans and adopted their manners, culture, customs, and practices.[9][17] They were looked down as non-Turks by Turks. Therefore, the Turkish nobles wrongly looked upon them as Afghans. They were considered Afghans in the Delhi Court.[18][19][20]

History

| Delhi Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruling dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Jalal-ud-din Khalji

Khaljis were vassals of the Mamluk dynasty of Delhi and served the Sultan of Delhi, Ghiyas ud din Balban. Balban's successors were murdered over 1289-1290, and the Mamluk dynasty succumbed to the factional conflicts within the Mamluk dynasty and the Muslim nobility. As the struggle between the factions razed, Jalal ud din Firuz Khalji led a coup and murdered the 17-year-old Mamluk successor Muiz ud din Qaiqabad - the last ruler of Mamluk dynasty[21]

Jalaluddin Firuz Khalji, who was around 70 years old at the time of his ascension, was known as a mild-mannered, humble and kind monarch to the general public.[22][23]

Jalaluddin succeeded in overcoming the opposition of the Turkish nobles and ascended the throne of Delhi in January 1290.</ref> Jalal-ud-din was not universally accepted: During his six-year reign (1290–96), Balban's nephew revolted due to his assumption of power and the subsequent sidelining of nobility and commanders serving the Mamluk dynasty.[24] Jalal-ud-din suppressed the revolt and executed some commanders, then led an unsuccessful expedition against Ranthambhor and repelled a Mongol force on the banks of the Sind River in central India with the help of his nephew Juna Khan.[25]

Alauddin Khalji

Alauddin Khalji was the nephew and son-in-law of Jalal-ud-din, raided the Hindu Deccan peninsula and Deogiri - then the capital of the Hindu state of Maharashtra, looting their treasure.[21][26] He returned to Delhi in 1296, murdered his uncle who was also his father-in-law, then assumed power as Sultan.[27]

Ala al-din Khalji continued expanding Delhi Sultanate into South India, with the help of generals such as Malik Kafur and Khusraw Khan, collecting large war booty (Anwatan) from those they defeated.[28] His commanders collected war spoils from Hindu kingdoms, paid khums (one fifth) on ghanima (booty collected during war) to Sultan's treasury, which helped strengthen the Khalji rule.[29]

_black.png)

Alauddin Khalji reigned for 20 years. He attacked and seized Hindu states of Ranthambhor (1301 AD), Chittorgarh (1303), Māndu (1305) and plundered the wealthy state of Devagiri,[30] also withstood two Mongol raids.[31] Ala al-din is also known for his cruelty against attacked kingdoms after wars. Historians note him as a tyrant and that anyone Ala al-din Khalji suspected of being a threat to this power was killed along with the women and children of that family. In 1298, between 15,000 and 30,000 people near Delhi, who had recently converted to Islam, were slaughtered in a single day, due to fears of an uprising.[32] He also killed his own family members and nephews, in 1299-1300, after he suspected them of rebellion, by first gouging out their eyes and then beheading them.[26]

In 1308, Alauddin's lieutenant, Malik Kafur captured Warangal, overthrew the Hoysala Empire south of the Krishna River and raided Madurai in Tamil Nadu.[30] He then looted the treasury in capitals and from the temples of south India. Among these loots was the Warangal loot that included one of the largest known diamond in human history, the Koh-i-noor.[29] Malik Kafur returned to Delhi in 1311, laden with loot and war booty from Deccan peninsula which he submitted to Aladdin Khalji. This made Malik Kafur, born in a Hindu family and who had converted to Islam before becoming Delhi Sultanate's army commander, a favorite of Alauddin Khalji.[25]

In 1311, Alauddin ordered a massacre of between 15,000 and 30,000 Mongol settlers, who had recently converted to Islam, after suspecting them of plotting an uprising against him.[32][33]

The last Khalji sultans

Aladdin Khalji died in December 1315. Thereafter, the sultanate witnessed chaos, coup and succession of assassinations.[21] Malik Kafur became the sultan but lacked support from the amirs and was killed within a few months.

Over the next three years, another three sultans assumed power violently and/or were killed in coups. Following Malik Kafur's death, the amirs installed a six-year-old named Shihab-ud-din Omar as sultan and his teenage brother, Qutb ud din Mubarak Shah, as regent. Qutb killed his younger brother and appointed himself sultan. To win over the loyalty of the amirs and the Malik clan, Mubarak Shah offered Ghazi Malik the position of army commander in the Punjab. Others were given a choice between various offices and death. After ruling in his own name for less than four years, Mubarak Shah was murdered in 1320 by one of his generals, Khusraw Khan. Amirs persuaded Ghazi Malik – who was still army commander in the Punjab – to lead a coup. Ghazi Malik's forces marched on Delhi, captured Khusraw Khan and beheaded him. Upon becoming sultan, Ghazi Malik renamed himself Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq. He would become the first ruler of the Tughluq dynasty.[26]

Economic policy and administration

Alauddin Khalji changed the tax policies to strengthen his treasury to help pay the keep of his growing army and fund his wars of expansion.[34][35] He raised agriculture taxes from 20% to 50% – payable in grain and agricultural produce (or cash),[36] eliminating payments and commissions on taxes collected by local chiefs, banned socialization among his officials as well as inter-marriage between noble families to help prevent any opposition forming against him; he cut salaries of officials, poets and scholars in his kingdom.[34][35]

Alauddin Khalji enforced four taxes on non-Muslims in the Sultanate - jizya (poll tax), kharaj (land tax), kari (house tax) and chari (pasture tax).[37][38] He also decreed that his Delhi-based revenue officers assisted by local Muslim jagirdars, khuts, mukkadims, chaudharis and zamindars seize by force half of all produce any farmer generates, as a tax on standing crop, so as to fill sultanate granaries.[34][39][40] His officers enforced tax payment by beating up Hindu and Muslim middlemen responsible for rural tax collection.[34] Furthermore, Alauddin Khalji demanded, state Kulke and Rothermund, from his "wise men in the court" to create "rules and regulations in order to grind down the Hindus, so as to reduce them to abject poverty and deprive them of wealth and any form of surplus property that could foster a rebellion;[37] the Hindu was to be so reduced as to be left unable to keep a horse to ride on, to carry arms, to wear fine clothes, or to enjoy any of the luxuries of life".[34] At the same time, he confiscated all landed property from his courtiers and officers.[37] Revenue assignments to Muslim jagirdars were also cancelled and the revenue was collected by the central administration.[41] Henceforth, state Kulke and Rothermund, "everybody was busy with earning a living so that nobody could even think of rebellion."[37]

Alauddin Khalji taxation methods and increased taxes reduced agriculture output and the Sultanate witnessed massive inflation. In order to compensate for salaries that he had cut and fixed for Muslim officials and soldiers, Alauddin introduced price controls on all agriculture produce, goods, livestocks and slaves in kingdom, as well as controls on where, how and by whom these could be sold. Markets called shahana-i-mandi were created.[41][42][43] Muslim merchants were granted exclusive permits and monopoly in these mandi to buy and resell at official prices. No one other than these merchants could buy from farmers or sell in cities. Alauddin deployed an extensive network of Munhiyans (spies, secret police) who would monitor the mandi and had the power to seize anyone trying to buy or sell anything at a price different than the official controlled prices.[34][43][44] Those found violating these mandi rules were severely punished, such as by cutting out their flesh.[25] Taxes collected in form of seized crops and grains were stored in sultanate's granaries.[45] Over time, farmers quit farming for income and shifted to subsistence farming, the general food supply worsened in north India, shortages increased and Delhi Sultanate witnessed increasingly worse and extended periods of famines.[25][46] The Sultan banned private storage of food by anyone.[34] Rationing system was introduced by Alauddin as shortages multiplied; however, the nobility and his army were exempt from the per family quota-based food rationing system.[46] The shortages, price controls and rationing system caused starvation deaths of numerous rural people, mostly Hindus. However, during these famines, Khalji's sultanate granaries and wholesale mandi system with price controls ensured sufficient food for his army, court officials and the urban population in Delhi.[35][47] Price controls instituted by Khalji reduced prices, but also lowered wages to a point where ordinary people did not benefit from the low prices. The price control system collapsed shortly after the death of Alauddin Khalji, with prices of various agriculture products and wages doubling to quadrupling within a few years.[48]

Historical impact

The tax system introduced during the Khalji dynasty had a long term influence on Indian taxation system and state administration,

Alauddin Khalji's taxation system was probably the one institution from his reign that lasted the longest, surviving indeed into the nineteenth or even the twentieth century. From now on, the land tax (kharaj or mal) became the principal form in which the peasant's surplus was expropriated by the ruling class.

— The Cambridge Economic History of India: c.1200-c.1750, [49]

Slavery

Within Sultanate's capital city of Delhi, during Alauddin Khalji's reign, at least half of the population were slaves working as servants, concubines and guards for the Muslim nobles, amirs, court officials and commanders.[50] Slavery in India during Khalji, and later Islamic dynasties, included two groups of people - persons seized during military campaigns, and people who failed to pay tax on time. The first group were people seized during military campaigns.[51] The second group of people were revenue defaulters. If a family failed to pay the annual tax in full on time, their property was seized and even some cases all their family members seized then sold as slaves.[52] The institution of slavery and bondage labor became pervasive during the Khalji dynasty; male slaves were referred to as banda, qaid, ghulam, or burdah, while female slaves were called bandi, kaniz or laundi.

Architecture

Ala-ud-din Khalji is credited with the early Indo-Mohammedan architecture, a style and construction campaign that flourished during Tughlaq dynasty. Among works completed during Khalji dynasty, are Alai Darwaza - the southern gateway of Qutb complex enclosure, the Idgah at Rapri, and the Jamat Khana (Khizri) Mosque in Delhi.[53] The Alai Darwaza, completed in 1311, was included as part of Qutb Minar and its Monuments UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993.[54]

Perso-Arabic inscriptions on monuments have been traced to the Khalji dynasty era.[1]

Disputed historical sources

Historians have questioned the reliability of historical accounts about the Khalji dynasty. Genuine primary sources and historical records from 1260 to 1349 period have not been found.[55] One exception is the short chapter on Delhi Sultanate from 1302-1303 AD by Wassaf in Persia, which is duplicated in Jami al-Tawarikh, and which covers the Balban rule, start of Jalal-ud-din Chili's rule and circumstances of succession of Alauddin Khalji. A semi-fictional poetry (mathnawis) by Yamin al-Din Abul Hasan, also known as Amir Khusraw Dihlawi, is full of adulation for his employer, the reigning Sultan. Abu Hasan's adulation-filled narrative poetry has been used as source of Khalji dynasty history, but this is a disputed source.[55][56] Three historical sources, composed 30 to 115 years after the end of Khalji dynasty, are considered more independent but also questioned given the gap in time. These are Isami's epic of 1349, Diya-yi Barani's work of 1357 and Sirhindi's account of 1434, which possibly relied on now lost text or memories of people in Khalji's court. Of these Barani's text is the most referred and cited in scholarly sources.[55][57]

List of rulers of Delhi (1290–1320)

| Titular Name | Personal Name | Reign[58] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shāyista Khān

(Jalal-ud-din) |

Malik Fīroz ملک فیروز خلجی |

1290–1296 | |

| Ala-ud-din علاءالدین |

Ali Gurshasp علی گرشاسپ خلجی |

1296–1316 | |

| Shihab-ud-din شھاب الدین |

Umar Khan عمر خان خلجی |

1316 | |

| Qutb-ud-din قطب الدین |

Mubarak Khan مبارک خان خلجی |

1316–1320 | |

| Khusro Khan ended the Khalji dynasty in 1320. | |||

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 "Arabic and Persian Epigraphical Studies - Archaeological Survey of India". Asi.nic.in. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- 1 2 "Khalji Dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

This dynasty, like the previous Slave dynasty, was of Turkish origin, though the Khaljī tribe had long been settled in Afghanistan. Its three kings were noted for their faithlessness, their ferocity, and their penetration of the Hindu south.

- ↑ Dynastic Chart The Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 2, p. 368.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 80–89. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 62. ISBN 1-5988-4337-0. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ↑ Barua, Pradeep (2005). The state at war in South Asia. U of Nebraska Press. p. 437. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Gijsbert Oonk (2007). Global Indian Diasporas: Exploring Trajectories of Migration and Theory. Amsterdam University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-90-5356-035-8.

- ↑ Burjor Avari (2013). Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A History of Muslim Power and Presence in the Indian Subcontinent. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-415-58061-8.

The Khaljis were a Turkic people who had long been settled in Afghanistan.

- 1 2 Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava 1953, p. 150.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani 1999, p. 181.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani 1999, pp. 181-182.

- 1 2 3 Sunil Kumar 1994, p. 36.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani 1999, pp. 180-181.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani 1999, pp. 180.

- 1 2 Sunil Kumar 1994, p. 31.

- ↑ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 82.

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish 2006, p. 320:"The members of the new dynasty, although they were also Turkic, had settled in Afghanistan and brought a new set of customs and culture to Delhi."

- ↑ Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava 1966, p. 98:"His ancestors, after having migrated from Turkistan, had lived for over 200 years in the Helmand valley and Lamghan, parts of Afghanistan called Garmasir or the hot region, and had adopted Afghan manners and customs. They were, therefore, wrongly looked upon as Afghans by the Turkish nobles in India as they had intermarried with local Afghans and adopted their customs and manners. They were looked down as non Turks by Turks"

- ↑ Abraham Eraly 2015, p. 126:"The prejudice of Turks was however misplaced in this case, for Khaljis were actually ethnic Turks. But they had settled in Afghanistan long before the Turkish rule was established there, and had over the centuries adopted Afghan customs and practices, intermarried with the local people, and were therefore looked down on as non-Turks by pure-bred Turks."

- ↑ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia 2002, p. 28:"The Khaljis were a Turkish tribe but having been long domiciled in Afghanistan, had adopted some Afghan habits and customs. They were treated as Afghans in Delhi Court. They were regarded as barbarians. The Turkish nobles had opposed the ascent of Jalal-ud-din to the throne of Delhi."

- 1 2 3 Peter Jackson 2003.

- ↑ Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava 1966, p. 141.

- ↑ A. B. M. Habibullah (1992) [1970]. "The Khaljis: Jalaluddin Khalji". In Mohammad Habib; Khaliq Ahmad Nizami. A Comprehensive History of India. 5: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. p. 312. OCLC 31870180.

- ↑ Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 81-86.

- 1 2 3 4 Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, Chapter 2, Oxford University Press

- 1 2 3 William Wilson Hunter, The Indian Empire: Its Peoples, History, and Products, p. 334, at Google Books, WH Allen & Co., London, pp 334-336

- ↑ P. M. Holt et al. 1977, pp. 8-14.

- ↑ Frank Fanselow (1989), Muslim society in Tamil Nadu (India): an historical perspective, Journal Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs, 10(1), pp 264-289

- 1 2 3 Hermann Kulke & Dietmar Rothermund 2004.

- 1 2 Sastri (1955), pp 206–208

- ↑ "Khalji Dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- 1 2 Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 231-235, Oxford University Press

- ↑ The Life and Works of Sultan Alauddin Khalji- By Ghulam Sarwar Khan Niazi

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hermann Kulke & Dietmar Rothermund 2004, p. 171-174.

- 1 2 3 P. M. Holt et al. 1977, pp. 9-13.

- ↑ Irfan Habib 1982, pp. 61-62.

- 1 2 3 4 Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund (1998), A History of India, 3rd Edition, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-15482-0, pp 161-162

- ↑ Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 196-202.

- ↑ Elliot and Dowson (1871), The History of India as told by its own Historians, p. 182, at Google Books, Vol. 3, pp 182-188

- ↑ N. Jayapalan (2008), Economic History of India: Ancient to Present Day, Atlantic Publishers, pp. 81-83, ISBN 978-8-126-90697-0

- 1 2 Kenneth Kehrer (1963), The Economic Policies of Ala-ud-Din Khalji, Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society, vol. 16, pp. 55-66

- ↑ Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava 1953, pp. 156-158.

- 1 2 Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 244-248.

- ↑ M.A. Farooqi (1991), The economic policy of the Sultans of Delhi, Konark publishers, ISBN 978-8122002263

- ↑ Irfan Habib (1984), The price regulations of Alauddin Khalji - a defense of Zia Barani, Indian Economic and Social History Review, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 393-414

- 1 2 K.S. Lal (1967), History of the Khaljis, Asian Publishing House, ISBN 978-8121502115, pp 201-204

- ↑ Vincent A Smith (1983), The Oxford History of India, Oxford University Press, pp 245-247

- ↑ Irfan Habib 1982, pp. 87-88.

- ↑ Irfan Habib 1982, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri et al (1982), The Cambridge Economic History of India: c. 1200-1750, Orient Longman, pp 89-93

- ↑ Irfan Habib (1978), Economic history of the Delhi Sultanate: An essay in interpretation, Indian Council of Historical Research, Vol 4, No. 2, pp 90-98, 289-297

- ↑ Scott Levi (2002), Hindu beyond Hindu Kush: Indians in Central Asian Slave Trade, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol 12, Part 3, pp 281-283

- ↑ Alexander Cunningham (1873), Archaeological Survey of India, Report for the year 1871-72, Volume 3, page 8

- ↑ UNESCO, Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi, World Heritage Site

- 1 2 3 Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 49-52.

- ↑ Elliot and Dawson (1871), The History of India as told by its own Historians, Vol. 3, pp 94-98

- ↑ Irfan Habib (1981), "Barani's theory of the history of the Delhi Sultanate", Indian Historical Review, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp 99-115

- ↑ Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 385.

- ↑ Peter Gottschalk (27 October 2005). Beyond Hindu and Muslim: Multiple Identity in Narratives from Village India. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-19-976052-7.

- ↑ Heramb Chaturvedi (2016). Allahabad School of History 1915-1955. Prabhat. p. 222. ISBN 978-81-8430-346-9.

Bibliography

- Abraham Eraly (2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin Books. p. 178. ISBN 978-93-5118-658-8.

- Ahmad Hasan Dani (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1540-7.

- Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava (1966). The History of India, 1000 A.D.-1707 A.D. (Second ed.). Shiva Lal Agarwala. OCLC 575452554.

- Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava (1953). The Sultanate of Delhi. S. L. Agarwala. OCLC 555201052.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- Irfan Habib (1982). "Northern India under the Sultanate: Agrarian Economy". In Tapan Raychaudhuri; Irfan Habib. The Cambridge Economic History of India. 1, c.1200-c.1750. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-22692-9.

- Kishori Saran Lal (1950). History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Allahabad: The Indian Press. OCLC 685167335.

- Marshall Cavendish (2006). World and Its Peoples: The Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 0-7614-7571-0.

- Peter Malcolm Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29138-5.

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic. ISBN 81-269-0123-3.

- Sunil Kumar (1994). "When Slaves were Nobles: The Shamsi Bandagan in the Early Delhi Sultanate". Studies in History. 10 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1177/025764309401000102.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Khalji dynasty |

![]()

- Khilji - A Short History of Muslim Rule in India I. Prasad, University of Allahabad

- The Role of Ulema in Indo-Muslim History, Aziz Ahmad, Studia Islamica, No. 31 (1970), pp. 1–13