Harrisonburg, Virginia

Harrisonburg is an independent city in the Shenandoah Valley region of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. It is also the county seat of the surrounding Rockingham County,[8] although the two are separate jurisdictions. As of the 2010 census, the population was 48,914,[9] with a census-estimated 2019 population of 53,016.[5] The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Harrisonburg with Rockingham County for statistical purposes into the Harrisonburg, Virginia Metropolitan Statistical Area, which has a 2011 estimated population of 126,562.[10]

Harrisonburg, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| City of Harrisonburg | |

Rockingham County Courthouse in Court Square in downtown Harrisonburg | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Friendly City, Rocktown, H'burg, The Burg, Friendly by Nature | |

Harrisonburg  Harrisonburg  Harrisonburg | |

| Coordinates: 38°26′58″N 78°52′08″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | None (Independent city) |

| Founded | 1779 |

| Incorporated | 1916 |

| Founded by | Thomas Harrison |

| Named for | Thomas Harrison |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager government |

| • City Manager | Eric Campbell[1] |

| • Mayor | Deanna R. Reed (D)[2] |

| • City Council[3] | Council Members

|

| • House Delegate | Tony Wilt (R) |

| • State Senator | Mark Obenshain (R) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17.39 sq mi (45.04 km2) |

| • Land | 17.34 sq mi (44.91 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.13 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,325 ft (404 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 48,914 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 53,016 |

| • Density | 2,800/sq mi (1,100/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 22801–22803, 22807 |

| Area code(s) | 540 |

| FIPS code | 51-35624[6] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1498489[7] |

| Website | www.harrisonburgva.gov |

Harrisonburg is home to James Madison University (JMU), a public research university with an enrollment of over 20,000 students,[11] and Eastern Mennonite University (EMU), a private, Mennonite-affiliated liberal arts university. Although the city has no historical association with President James Madison, JMU was nonetheless named in his honor as Madison College in 1938 and renamed as James Madison University in 1977.[12] EMU largely owes it existence to the sizable Mennonite population in the Shenandoah Valley, to which many Pennsylvania Dutch settlers arrived beginning in the mid-18th century in search of rich, unsettled farmland.[13]

The city has become a bastion of ethnic and linguistic diversity in recent years. Over 1,900 refugees have been settled in Harrisonburg since 2002.[14] As of 2014, Hispanics or Latinos of any race comprise 19% of the city's population.[15] Harrisonburg City Public Schools (HCPS) students speak 55 languages in addition to English, with Spanish, Arabic, and Kurdish being the most common languages spoken.[16] Over one-third of HCPS students are English as a second language (ESL) learners.[17] Language learning software company Rosetta Stone was founded in Harrisonburg in 1992,[18] and the multilingual "Welcome Your Neighbors" yard sign originated in Harrisonburg in 2016.[14]

History

The earliest documented English exploration of the area prior to settlement was the "Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition", led by Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood, who reached Elkton, and whose rangers continued and in 1716 likely passed through what is now Harrisonburg.

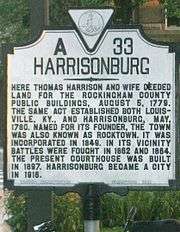

Harrisonburg, previously known as "Rocktown", was named for Thomas Harrison, a son of English settlers.[20] In 1737, Harrison settled in the Shenandoah Valley, eventually laying claim to over 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) situated at the intersection of the Spotswood Trail and the main Native American road through the valley.[21]

In 1779, Harrison deeded 2.5 acres (1.0 ha) of his land to the "public good" for the construction of a courthouse. In 1780, Harrison deeded an additional 50 acres (20 ha).[22] This is the area now known as "Historic Downtown Harrisonburg."

In 1849, trustees chartered a mayor–council form of government, although Harrisonburg was not officially incorporated as an independent city until 1916. Today, a council–manager government administers Harrisonburg.[23]

On June 6, 1862, an American Civil War skirmish took place at Good's Farm, Chestnut Ridge near Harrisonburg between the forces of the Union and the forces of the Confederacy at which the C.S. Army Brigadier General, Turner Ashby (1828–1862), was killed.

Newtown

When the slaves of the Shenandoah Valley were freed in 1865, they set up near modern-day Harrisonburg a town called Newtown.[24] This settlement was eventually annexed by the independent city of Harrisonburg some years later, probably around 1892. Today, the old city of Newtown is in the Northeast section of Harrisonburg and which is referred to as Downtown Harrisonburg.[25] It remains the home of the majority of Harrisonburg's predominantly black churches, such as the First Baptist and Bethel AME. The modern Boys and Girls Club of Harrisonburg is located in the old Lucy Simms schoolhouse used for the black students in the days of segregation.[26]

Project R4 and R16

A large portion of this black neighborhood was dismantled in the 1960s when – in the name of urban renewal – the city government used federal redevelopment funds from the Housing Act of 1949 to force black families out of their homes and then bulldozed the neighborhood. This effort, called "Project R-4", focused on the city blocks east of Main, north of Gay, west of Broad, and south of Johnson. This area makes up 32.5 acres. "Project R-16" is a smaller tag on project which focused on the 7.5 acres south of Gay street.[27][25][28][29][30]

According to Bob Sullivan, an intern working in the city planner's office in 1958, the city planner at the time, David Clark had to convince the city council that Harrisonburg even had slums. Newtown, a low socioeconomic status housing area, was declared a slum. Federal law mandated that the city needed to have a referendum on the issue before R4 could begin. The vote was close with 1,024 votes in favor and 978 against R4. Following the vote, the Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority was established in 1955 to carry out the project. All of the members were white men. The project began and, due to eminent domain, the government could force the people of Newtown to sell their homes.[31] They were offered rock bottom prices for their homes. Many people couldn't afford a new home and had to move into public housing projects and become dependent on the government. Other families left Harrisonburg. It is estimated between 93 and 200 families were displaced.[28][27]

In addition to families, many of the businesses of Newtown that were bought out could not afford to reestablish themselves. Locals say many prominent black businesses like the Colonnade which served as a pool hall, dance hall, community center, and tearoom were unable to reopen.[32] Kline's, a white-owned business, was actually one of the few businesses in the area that was able to reopen. The city later made $500,000 selling the seized property to redevelopers. Before the project, the area brought in $7000 in taxes annually. By 1976, The areas redeveloped in R4 and R16 were bringing in $45,000 in annual taxes.These profit gains led Lauren McKinney to regard the project as “one of only two ‘profitable’ redevelopment schemes in the state of Virginia.” [27]

Cultural landmarks were also influenced by the projects. Although later rebuilt, The Old First Baptist Church of Harrisonburg was demolished.[32][33] Newtown Cemetery, a Historic African American Cemetery, was also impacted. It appears no Burials were destroyed, however, the western boundary was paved over and several headstones now touch the street.[34][32]

Infrastructure

_in_Harrisonburg%2C_Virginia.jpg)

Major highways in Harrisonburg include Interstate 81, the main north-south highway in western Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. Other significant roads serving the city include U.S. Route 11, U.S. Route 33, Virginia State Route 42, Virginia State Route 253 and Virginia State Route 280.

In early 2002, the Harrisonburg community discussed the possibility of creating a pedestrian mall downtown. Public meetings were held to discuss the merits and drawbacks of pursuing such a plan. Ultimately, the community decided to keep its Main Street open to traffic. From these discussions, however, a strong voice emerged from the community in support of downtown revitalization.

On July 1, 2003, Harrisonburg Downtown Renaissance was incorporated as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization with the mission of rejuvenating the downtown district.[35]

In 2004, downtown was designated as the Harrisonburg Downtown Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places and a designated Virginia Main Street Community,[36] with the neighboring Old Town Historic District residential community gaining historic district status in 2007. Several vacant buildings have been renovated and repurposed for new uses, such as the Hardesty-Higgins House and City Exchange, used for the Harrisonburg Tourist Center and high-end loft apartments, respectively.

In 2008, downtown Harrisonburg spent over $1 million in cosmetic and sidewalk infrastructure improvements (also called streetscaping and wayfinding projects). The City Council appropriated $500,000 for custom street signs to be used as "wayfinding signs" directing visitors to areas of interest around the city. Another $500,000 were used to upgrade street lighting, sidewalks, and landscaping along Main Street and Court Square.[37]

In 2014, Downtown Harrisonburg was named a Great American Main Street by the National Main Street Association and downtown was designated the first culinary district in the commonwealth of Virginia.

Norfolk Southern also owns a small railyard in Harrisonburg. The Chesapeake and Western corridor from Elkton to Harrisonburg has very high volumes of grain and ethanol. The railroad serves two major grain elevators inside the city limits. In May 2017 Norfolk Southern 51T derailed in Harrisonburg spilling corn into Blacks Run. No one was injured.

Shenandoah Valley Railroad interchanges with the NS on south side of Harrisonburg and with CSX and Buckingham Branch Railroad in North Staunton.

Harrisonburg Transit provides public transportation in Harrisonburg. Virginia Breeze provides intercity bus service between Blacksburg, Harrisonburg, and Washington, D.C..[38]

Culture

Harrisonburg has won several awards[39] in recent years, including "#6 Favorite Town in America" by Travel + Leisure in 2016,[40] the "#15 Best City to Raise an Outdoor Kid" by Backpacker in 2009,[41] and the "#3 Happiest Mountain Town" by Blue Ridge Country Magazine in 2016.[42]

Harrisonburg holds the title of "Virginia's first Culinary District" (awarded in 2014).[43] The "Taste of Downtown" (TOD) week-long event takes place annually to showcase local breweries and restaurants.[44] Often referred to as "Restaurant Week," the TOD event offers a chance for culinary businesses in downtown Harrisonburg to create specials, collaborations, and try out new menus.[45]

The creative class of Harrisonburg has grown alongside the revitalization of the downtown district. The designation of "first Arts & Cultural District in Virginia" was awarded to Downtown Harrisonburg in 2001.[46] Contributing to Harrisonburg's cultural capital are a collection of education and art centers, residencies, studios, and artist-facilitated businesses, programs, and collectives.

Some of these programs include:

- Larkin Arts, a community art center that opened in 2012 and has four symbiotic components: an art supply store, a fine arts gallery, a school with three classrooms, and five private studio spaces.[47][48]

- Old Furnace Artist Residency (OFAR)[49] and SLAG Mag: Artist residency and arts&culture quarterly zine focused on community engagement and social practice projects started in 2013.[50]

- The Super Gr8 Film Festival, founded in 2009. The 2013 festival featured more than 50 locally produced films, and all of the films in the festival were shot using vintage cameras and Super 8 film.[51]

- Arts Council of the Valley, including the Darrin-McHone Gallery and Court Square Theater, provides facilities and funding for various arts programs and projects.[52]

- OASIS Fine Art and Craft, opened in 2000, is a cooperative gallery of over 35 local artists and artisans exhibiting and selling their work. It offers fine hand-crafted pottery, jewelry, fiber art, wood, metal, glass, wearable art, paintings, and photography.[53]

- The Virginia Quilt Museum, established in 1995, is dedicated to preserving, celebrating, and nurturing Virginia's quilting heritage. It features a permanent collection of nearly 300 quilts, a Civil War Gallery, antique and toy sewing machines, and rotating exhibits from across the United States.[54]

Historic sites

In addition to the Hardesty-Higgins House, Thomas Harrison House, Harrisonburg Downtown Historic District, and Old Town Historic District, the Anthony Hockman House, Rockingham County Courthouse, Lucy F. Simms School, Whitesel Brothers, and Joshua Wilton House are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[55]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 17.4 square miles (45.1 km2), of which 17.3 square miles (44.8 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km2) (0.3%) is water.[56]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,023 | — | |

| 1870 | 2,036 | 99.0% | |

| 1880 | 2,831 | 39.0% | |

| 1890 | 2,792 | −1.4% | |

| 1900 | 3,521 | 26.1% | |

| 1910 | 4,879 | 38.6% | |

| 1920 | 5,875 | 20.4% | |

| 1930 | 7,232 | 23.1% | |

| 1940 | 8,768 | 21.2% | |

| 1950 | 10,810 | 23.3% | |

| 1960 | 11,916 | 10.2% | |

| 1970 | 14,605 | 22.6% | |

| 1980 | 19,671 | 34.7% | |

| 1990 | 30,707 | 56.1% | |

| 2000 | 40,468 | 31.8% | |

| 2010 | 48,914 | 20.9% | |

| Est. 2019 | 53,016 | [5] | 8.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[57] 1790-1960[58] 1900-1990[59] 1990-2000[60] 2010-2012[9] | |||

As of the census[61] of 2010, 48,914 people, 15,988 households, and 7,515 families resided in the city. The population density was 2,811.1/mi2 (1087.0/km²). The 15,988 housing units averaged 918.9/mi2 (355.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 78.4% White, 6.4% Black or African American, 0.3% Native American, 3.5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 8.2% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 15.7% of the population, up from 8.85% according to the census of 2000.

Of the 15,988 households, 22.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 32.7% were married couples living together, 10.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 53.0% were not families. About 27.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59, and the average family size was 3.06.

In the city, the population was distributed as 15.0% under the age of 18, 48.9% from 18 to 24, 21.2% from 25 to 44, 13.2% from 45 to 64, and 9.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $37,850, and for a family was $53,642. The per capita income for the city was $16,992. About 11.5% of families and 31.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.6% of those under age 18 and 9.5% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 34.8% 6,262 | 56.8% 10,212 | 8.4% 1,513 |

| 2012 | 42.1% 6,565 | 55.5% 8,654 | 2.4% 374 |

| 2008 | 41.2% 6,048 | 57.5% 8,444 | 1.3% 183 |

| 2004 | 55.9% 6,165 | 42.9% 4,726 | 1.3% 139 |

| 2000 | 57.7% 5,741 | 35.0% 3,482 | 7.4% 735 |

| 1996 | 55.3% 4,945 | 37.4% 3,346 | 7.2% 646 |

| 1992 | 51.2% 4,935 | 35.4% 3,414 | 13.3% 1,283 |

| 1988 | 64.9% 5,376 | 33.8% 2,799 | 1.4% 113 |

| 1984 | 68.2% 5,221 | 31.1% 2,384 | 0.7% 56 |

| 1980 | 58.5% 3,388 | 32.7% 1,896 | 8.8% 512 |

| 1976 | 63.0% 3,376 | 33.7% 1,803 | 3.3% 179 |

| 1972 | 77.3% 3,626 | 21.1% 992 | 1.6% 75 |

| 1968 | 65.7% 2,859 | 23.8% 1,036 | 10.5% 457 |

| 1964 | 50.7% 1,820 | 49.2% 1,765 | 0.1% 5 |

| 1960 | 72.0% 2,172 | 27.7% 836 | 0.2% 7 |

| 1956 | 78.3% 2,265 | 19.7% 571 | 2.0% 57 |

| 1952 | 77.8% 2,238 | 22.1% 635 | 0.1% 3 |

| 1948 | 58.6% 1,377 | 31.9% 751 | 9.5% 224 |

| 1944 | 50.0% 1,302 | 49.7% 1,292 | 0.3% 8 |

| 1940 | 40.3% 1,000 | 58.9% 1,462 | 0.8% 19 |

| 1936 | 38.9% 894 | 60.5% 1,390 | 0.6% 13 |

| 1932 | 39.3% 665 | 58.8% 995 | 1.9% 32 |

| 1928 | 62.7% 1,037 | 37.3% 616 | |

| 1924 | 49.7% 631 | 49.1% 624 | 1.2% 15 |

| 1920 | 53.9% 704 | 45.5% 594 | 0.7% 9 |

| 1916 | 47.6% 319 | 51.6% 346 | 0.8% 5 |

Like most of the Shenandoah Valley, Harrisonburg has traditionally been a Republican stronghold. It was one of the first areas of Virginia where old-line Southern Democrats began splitting their tickets. The city went Republican at every presidential election from 1944 to 2004. In 2008, however, Barack Obama carried the city by a margin of 16 percent—exceeding the margin by which George W. Bush carried it four years earlier. The city has gone Democratic in every presidential election since then, and has become one of the few Democratic mainstays in one of the more conservative parts of Virginia.

Education

School systems

Serving about 4,400 students (K–12), Harrisonburg City Public Schools comprises six elementary schools, two middle schools, and a high school. Eastern Mennonite School, a private school, serves grades K–12 with an enrollment of about 386 students.[63]

Higher education

- James Madison University (public)

- Eastern Mennonite University (private, Mennonite-affiliated)

- National College (private, for-profit)

- American National University (private, for-profit)

High schools

Middle schools

- Skyline Middle School

- Thomas Harrison Middle School

Elementary schools

- Bluestone Elementary

- Smithland Elementary

- Spotswood Elementary

- Stone Spring Elementary

- Waterman Elementary

- W.H. Keister Elementary

Private schools

- Blue Ridge Christian School

- Eastern Mennonite School

- Redeemer Classical School (K–8)

Points of interest

- Hardesty-Higgins House Visitor Center

- Edith J. Carrier Arboretum

- Downtown Harrisonburg

- Harrisonburg's Old Post Office Mural (Now US Bankruptcy Court)

- Virginia Quilt Museum - located downtown and dedicated to preserving, celebrating, and nurturing Virginia's quilting heritage. The museum was established in 1995 and features a permanent collection of nearly 300 quilts, a Civil War Gallery, antique and toy sewing machines, and rotating exhibits from across the United States.[54]

Events

- The Alpine Loop Gran Fondo road-cycling event hosted by professional cyclist Jeremiah Bishop starts and finishes in downtown Harrisonburg.[64]

- The annual Harrisonburg International Festival celebrates international foods, dance, music, and folk art.[65]

- Valley Fourth - Downtown Harrisonburg's Fourth of July celebrations that bring in over 12,000 people. The festival includes a morning run, food trucks, beer and music garden, kids' area, art market, craft and clothing vendors, and fireworks.

- Christmas/Holiday Parade- dates vary.

- Taste of Downtown - food event, yearly in March.

- MACROCK - an independent music conference held in the downtown area of Harrisonburg, Virginia the first weekend of April annually since 1997

- Skeleton Festival - This event blends aspects of Halloween and Dia de los Muertos in a big, community celebration. Activities kick off with trick-or-treating at downtown businesses and culminate with a fun, all-ages party at the Turner Pavilion & Park. The festival features kid, dog, and adult costume contests; face painting; fire dancing; food trucks; live music; a community ofrenda; video art; "trunk or treating"; wacky shacks, goober blobs and whisker biscuits. www.skeletonfestival.com

- Rocktown Beer & Music Festival- This event is very well attended each Spring. It features over 75 different beers and ciders. The band lineup changes each year and food is supplied by some of the local downtown restaurants. www.rocktownfestival.com

Sports

- Eastern Mennonite Royals (NCAA Division III, Old Dominion Athletic Conference)

- 2010 Division III Men's Basketball Elite 8 qualifiers

- 2004 Women's Basketball Sweet 16 qualifiers

- Harrisonburg Turks (Valley Baseball League)

- James Madison Dukes (NCAA Division I, Football Championship Subdivision, Colonial Athletic Association)

- 1994 NCAA Division I Field Hockey Championship National Champions

- 2004 Division I-AA National Champions

- 2016 NCAA Division I Football Championship National Champions

- 2018 NCAA Division I Women's Lacrosse Championship National Champions

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally cool to cold winters. Harrisonburg has a humid subtropical climate, Cfa on climate maps according to the Köppen climate classification, but has four clearly defined seasons that vary significantly, if not having brief changes from summer to winter.[66] The USDA hardiness zone is 6b, which means average minimum winter temperature of −5 to 0 °F (−21 to −18 °C).

Notable people

Born

- Brian Bocock, former MLB player

- Pasco Bowman II, Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (1983–1999)

- Nelson Chittum, former MLB player

- James H. Cravens, U.S. Representative from Indiana (1841–1843)

- Clement Conger, White House Curator (1970–1990)

- Dell Curry, former NBA player; father of NBA players Stephen Curry and Seth Curry

- Donald DePoy, fifth-generation bluegrass musician, music educator, and music event organizer

- Page Dunlap, former LPGA Tour member and 1986 winner of the individual NCAA Division I Women's Golf Championship

- Dan Forest, 34th Lieutenant Governor of North Carolina (2013–present)

- Alan Knicely, former MLB player

- Tom Lough, former modern pentathlete and competitor in the 1968 Summer Olympics[67]

- Old Crow Medicine Show, Americana string band

- John Paul Jr., U.S. Representative from Virginia (1922-1923); U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Virginia (1929-1932); Judge for the Western District of Virginia (1932-1958), whose school desegregation rulings set off Massive Resistance by Virginia officials

- Thomas F. Riley, Brigadier general in the Marine Corps, later served as Orange County Supervisor 1974-1994

- Kaitlyn Vincie, Fox NASCAR reporter and NASCAR Race Hub presenter

Raised

- Samuel B. Avis, U.S. Representative from West Virginia (1913–1915)

- John H. Gibbons, nuclear physicist; Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (1993–1998)

- William Conrad Gibbons, historian and Vietnam War expert

- Akeem Jordan, current NFL player

- Edgar Amos Love, co-founder of Omega Psi Phi fraternity

- John Otho Marsh Jr., U.S. Representative from Virginia (1963–1971); Secretary of the Army (1981–1989)

- Bill Mims, Justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia (2010–present); former Attorney General of Virginia (2009–2010)

- Ralph Sampson, former NBA player

- Howard Stevens, former NFL player

- Maggie Stiefvater, bestselling young adult fiction author

- Josh Sundquist, paralympian, bestselling author, and motivational speaker

- Kristi Toliver, current WNBA player and NBA assistant coach

- Landon Turner, current NFL player

- John Wade, former NFL player

Resident

- Jeremiah Bishop, cross-country mountain bike racer

- John T. "Judge" Harris, U.S. Representative from Virginia (1859–1861, 1871–1881)

- Daryl Irvine, former MLB player

- John R. Jones, brigadier general in Confederate States Army

- Gus Niarhos, former MLB player

- Mark Obenshain, Republican nominee in Virginia Attorney General Election of 2013; member of the Senate of Virginia (2004–present)

- Charles Triplett "Trip" O'Ferrall, U.S. Representative for Virginia (1883-1894), 42nd Governor of Virginia (1894–1898)

- John Birdsell Oren, U.S. Coast Guard Rear admiral

- Sofia Samatar, award-winning writer[68]

- Howard Zehr, pioneer of restorative justice

See also

- Harrisonburg Department of Public Transportation

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Harrisonburg, Virginia

- Virginia Mennonite Conference

References and notes

- "City Manager Eric Campbell". Harrisonburgva.gov. August 24, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- 2017–2021;

- "City Council | City of Harrisonburg, VA". Harrisonburgva.gov. August 24, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "2018 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Harrisonburg – Populated Place". Geographic Names Information System. USGS. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2011". 2011 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. April 20, 2009. Archived from the original (CSV) on April 27, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- "JMU Facts & Figures". James Madison University. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "JMU Historical Timeline". JMU Centennial Office. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- Schum, Guy (February 14, 2012). "The Plain People". Virginialiving.com. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Where Did Those 'We're Glad You're Our Neighbor' Signs Come From?". WAMU.org. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- USA (April 1, 2000). "Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends". Pewhispanic.org. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "ESL Students in HCPS". Harrisonburg.k12.va.us. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Harrisonburg City Schools - English as a Second Language". Harrisonburg.k12.va.us. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Rosetta Stone History". Rosettastone.com. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- Kane, Joseph Nathan, Aiken, Charles Curry (2004). The American Counties. Scarecrow Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-8108-5036-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Harrison, J. Houston (1935). Settlers by the Long Grey Trail J.K. Ruebush. p 214-249

- Julian Smith, 2007, Moon Virginia p. 246

- "A Brief History of Harrisonburg". Harrisonburgva.gov. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Government Structure of Harrisonburg". Harrisonburgva.gov. April 8, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- Stephens City, Virginia was also called Newtown at this time.

- Hagi, Randi B. "The Legacy of Harrisonburg's 'Urban Renewal'". www.wmra.org. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Welcome [landing page]". Celebrating Simms: The story of the Lucy F. Simms School. James Madison University & the Shenandoah Valley Black Heritage Center in association with Billo Harper. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- Hagi, Randi B. "The Role of Race and Money in Harrisonburg's 'Urban Renewal'". www.wmra.org. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Remembering Project R4". Eightyone.info. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "projects r-4 and r-16". Shenandoah Living Archive Prototype. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Harrisonburg's Urban Renewal Projects, R4 & R16". Learn Share Illuminate. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "A GUIDE TO THE HARRISONBURG REDEVELOPMENT & HOUSING AUTHORITY PHOTOGRAPHS, 1960-1987: SC 0235," Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority Photographs, 1960-1987, SC 0235, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA. https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=jmu/vihart00185.xml

- "Mapping African American Life in Harrisonburg". public.imaginingamerica.org. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "First Baptist History". firstbaptisthbgva.org. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Newtown Cemetery National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). December 20, 2014.

- Bolsinger, Andrew Scot (October 28, 2002). "Downtown". Daily News-Record. Harrisonburg, VA. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "Harrisonburg Downtown Historic District". Virginia Main Street Community: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary. National Park Service. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- Creswell, Kelly (August 14, 2007). "Harrisonburg Streetscape". WHSV TV 3. Gray Television, Inc. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "The Virginia Breeze: Bus from Blacksburg to Washington, DC". The Virginia Breeze: Bus from Blacksburg to Washington, DC | DRPT. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Awards and Recognitions". City of Harrisonburg, VA. July 10, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- "America's Favorite Towns". Travel + Leisure. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- "The Best Cities to Raise an Outdoor Kid: The Winning 25 - Page 3 of 6 - Backpacker". Backpacker. July 1, 2009. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- "The Top 61 Happiest Mountain Towns in the Blue Ridge". BlueRidgeCountry.com. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- Hellman, Reed (August 14, 2017). "'Farm to table' means just that in Virginia's first Culinary District". Recreation News. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- "Annual Events". Downtown Harrisonburg. Harrisonburg Downtown Renaissance. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- "Taste of Downtown". Downtown Harrisonburg. Harrisonburg Downtown Renaissance. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- "Main Street vibe". Harrisonburg, VA: Friendly by Nature. Harrisonburg Tourism. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- "SCCF OUT & ABOUT: LARKIN ARTS, HARRISONBURG". Staunton Creative Community Fund. September 17, 2012. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- Stacy, Sarah. "Larkin Arts hosts second annual juried art show". DNR Harrisonburg. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014.

- "2014 Open Engagement Program". Open Engagement.

- Jenner, Andrew. "Visiting With the Old Furnace Artist Residency". Old South High. Old South High. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- Jenkins, Jermiah. "Lurid Pictures + Super Gr8 Film Fest = Awesome Harrisonburg". Old South High. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- "About Us". Arts Council of the Valley. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- "Home - OASIS Fine Art & Craft". Oasisfineartandcraft.org. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Virginia Quilt Museum". VQM.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- David Leip. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". Uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- Eastern Mennonite School profile Archived July 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- "Alpine Loop Gran Fondo". Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- "Harrisonburg International Festival". Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- "Climate Summary for Harrisonburg, Virginia". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Tom Lough Olympic Results". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- Samatar, Sofia (2018). From The White Mosque CMW Journal, vol. 10, no. 4. Retrieved 2019-16-01.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Harrisonburg. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harrisonburg, Virginia. |