Racial segregation in the United States

Racial segregation in the United States, as a general term, refers to the segregation of facilities, services, and opportunities such as housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation in the United States along racial lines. The term mainly refers to the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from European Americans, but it is also used with regards to the separation of other ethnic minorities from majority mainstream communities.[1] While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as the separation of roles within an institution. Notably, in the United States Armed Forces up until 1948, black units were typically separated from white units but were nevertheless still led by white officers.[2]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

| Segregation by region |

| Similar practices by region |

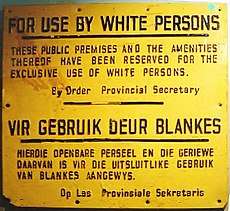

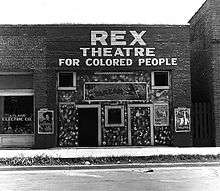

Signs were used to indicate where African Americans could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat.[3] Segregated facilities extended from white only schools to white only graveyards.[4] The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), so long as "separate but equal" facilities were provided, a requirement that was rarely met in practice.[5] The doctrine was overturned in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) unanimously by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, and in the following years the Warren Court further ruled against racial segregation in several landmark cases including Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964), which helped bring an end to the Jim Crow laws.[6][7][8][9]

Racial segregation follows two forms. De jure segregation mandated the separation of races by law, and was the form imposed by slave codes before the Civil War and by Black Codes and Jim Crow laws following the war. De jure segregation was outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.[10] In specific areas, however, segregation was barred earlier by the Warren Court in decisions such as the Brown v. Board of Education decision that overturned school segregation in the United States. De facto segregation, or segregation "in fact", is that which exists without sanction of the law. De facto segregation continues today in areas such as residential segregation and school segregation because of both contemporary behavior and the historical legacy of de jure segregation.[11]

History

Reconstruction in the South

Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1870 providing the right to vote, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875 forbidding racial segregation in accommodations. As a result, Federal occupation troops in the South assured blacks the right to vote and to elect their own political leaders. The Reconstruction amendments asserted the supremacy of the national state and the formal equality under the law of everyone within it. However, it did not prohibit segregation in schools.[13]

When the Republicans came to power in the Southern states after 1867, they created the first system of taxpayer-funded public schools. Southern Blacks wanted public schools for their children but they did not demand racially integrated schools. Almost all the new public schools were segregated, apart from a few in New Orleans. After the Republicans lost power in the mid-1870s, Southern Democrats retained the public school systems but sharply cut their funding. [14]

Almost all private academies and colleges in the South were strictly segregated by race.[15] The American Missionary Association supported the development and establishment of several historically black colleges, such as Fisk University and Shaw University. In this period, a handful of northern colleges accepted black students. Northern denominations and their missionary associations especially established private schools across the South to provide secondary education. They provided a small amount of collegiate work. Tuition was minimal, so churches supported the colleges financially, and also subsidized the pay of some teachers. In 1900, churches—mostly based in the North—operated 247 schools for blacks across the South, with a budget of about $1 million. They employed 1600 teachers and taught 46,000 students.[16][17] Prominent schools included Howard University, a federal institution based in Washington; Fisk University in Nashville, Atlanta University, Hampton Institute in Virginia, and many others. Most new colleges in the 19th century were founded in northern states.

By the early 1870s, the North lost interest in further reconstruction efforts and when federal troops were withdrawn in 1877, the Republican Party in the South splintered and lost support, leading to the conservatives (calling themselves "Redeemers") taking control of all the southern states. 'Jim Crow' segregation began somewhat later, in the 1880s.[18] Disfranchisement of the blacks began in the 1890s. Although the Republican Party had championed African-American rights during the Civil War and had become a platform for black political influence during Reconstruction, a backlash among white Republicans led to the rise of the lily-white movement to remove African Americans from leadership positions in the party and incite riots to divide the party, with the ultimate goal of eliminating black influence.[19] By 1910, segregation was firmly established across the South and most of the border region, and only a small number of black leaders were allowed to vote across the Deep South.[20]:117

Jim Crow era

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of blacks was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537. The Supreme Court sustained the constitutionality of a Louisiana statute that required railroad companies to provide "separate but equal" accommodations for white and black passengers, and prohibited whites and blacks from using railroad cars that were not assigned to their race.[22]

Plessy thus allowed segregation, which became standard throughout the southern United States, and represented the institutionalization of the Jim Crow period. Everyone was supposed to receive the same public services (schools, hospitals, prisons, etc.), but with separate facilities for each race. In practice, the services and facilities reserved for African-Americans were almost always of lower quality than those reserved for whites, if they existed at all; for example, most African-American schools received less public funding per student than nearby white schools. Segregation was never mandated by law in the Northern states, but a de facto system grew for schools, in which nearly all black students attended schools that were nearly all-black. In the South, white schools had only white pupils and teachers, while black schools had only black teachers and black students.[23]

Some streetcar companies did not segregate voluntarily. It took 15 years for the government to break down their resistance.[24]

On at least six occasions over nearly 60 years, the Supreme Court held, either explicitly or by necessary implication, that the "separate but equal" rule announced in Plessy was the correct rule of law,[25] although, toward the end of that period, the Court began to focus on whether the separate facilities were in fact equal.

The repeal of "separate but equal" laws was a major focus of the Civil Rights Movement. In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the Supreme Court outlawed segregated public education facilities for blacks and whites at the state level. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 superseded all state and local laws requiring segregation. However, compliance with the new law was glacial at best, and it took years with many cases in lower courts to enforce it.

New Deal era

The New Deal of the 1930s was racially segregated; blacks and whites rarely worked alongside each other in New Deal programs. The largest relief program by far was the Works Progress Administration (WPA); it operated segregated units, as did its youth affiliate, the National Youth Administration (NYA).[26] Blacks were hired by the WPA as supervisors in the North; however of 10,000 WPA supervisors in the South, only 11 were black.[27] Historian Anthony Badger argues, "New Deal programs in the South routinely discriminated against blacks and perpetuated segregation."[28] In its first few weeks of operation, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in the North were integrated. By July 1935, however, practically all the CCC camps in the United States were segregated, and blacks were strictly limited in the supervisory roles they were assigned.[29] Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith argue that "even the most prominent racial liberals in the New Deal did not dare to criticize Jim Crow."[30] Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes was one of the Roosevelt Administration's most prominent supporters of blacks and former president of the Chicago chapter of the NAACP. In 1937 when Senator Josiah Bailey Democrat of North Carolina accused him of trying to break down segregation laws, Ickes wrote him to deny that:

- I think it is up to the states to work out their social problems if possible, and while I have always been interested in seeing that the Negro has a square deal, I have never dissipated my strength against the particular stone wall of segregation. I believe that wall will crumble when the Negro has brought himself to a high educational and economic status…. Moreover, while there are no segregation laws in the North, there is segregation in fact and we might as well recognize this.[31][32]

Hypersegregation

In an often-cited 1988 study, Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton compiled 20 existing segregation measures and reduced them to five dimensions of residential segregation.[33] Dudley L. Poston, Michael Micklin argue that Massey and Denton "brought conceptual clarity to the theory of segregation measurement by identifying five dimensions".[34]

African Americans are considered to be racially segregated because of all five dimensions of segregation being applied to them within these inner cities across the U.S. These five dimensions are evenness, clustering, exposure, centralization and concentration.[35]

Evenness is the difference between the percentage of a minority group in a particular part of a city, compared to the city as a whole. Exposure is the likelihood that a minority and a majority party will come in contact with one another. Clustering is the gathering of different minority groups into a single space; clustering often leads to one big ghetto and the formation of hyperghettoization. Centralization measures the tendency of members of a minority group to be located in the middle of an urban area, often computed as a percentage of a minority group living in the middle of a city (as opposed to the outlying areas). Concentration is the dimension that relates to the actual amount of land a minority lives on within its particular city. The higher segregation is within that particular area, the smaller the amount of land a minority group will control.

The pattern of hypersegregation began in the early 20th century. African-Americans who moved to large cities often moved into the inner-city in order to gain industrial jobs. The influx of new African-American residents caused many European American residents to move to the suburbs in a case of white flight. As industry began to move out of the inner-city, the African-American residents lost the stable jobs that had brought them to the area. Many were unable to leave the inner-city, however, and they became increasingly poor.[36] This created the inner-city ghettos that make up the core of hypersegregation. Though the Civil Rights Act of 1968 banned discrimination in sale of homes, the norms set before the laws continue to perpetuate this hypersegregation.[37] Data from the 2000 census shows that 29 metropolitan areas displayed black-white hypersegregation; in 2000. Two areas—Los Angeles and New York City—displayed Hispanic-white hypersegregation. No metropolitan area displayed hypersegregation for Asians or for Native Americans.[38]

Racism

For much of the 20th century, it was a popular belief among many whites that the presence of blacks in white neighborhoods would bring down property values. The United States government began making low-interest mortgages available to families through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veteran's Administration. Black families were legally entitled to these loans but they were sometimes denied these loans because the planners who were behind this initiative labeled many black neighborhoods throughout the country as being "in decline". The rules for loans did not say that "black families cannot get loans"; rather, they said that people who were from "areas in decline" could not get loans.[39] While a case could be made that the wording did not appear to compel segregation, it tended to have that effect. In fact, this administration was formed as part of the New Deal for all Americans but it mostly affected black residents of inner city areas; most black families did in fact live in the inner city areas of large cities and they almost entirely occupied these areas after the end of World War II when whites began to move to new suburbs.[40]

In addition to encouraging white families to move into suburbs by granting them loans which enabled them to do so, the government uprooted many established African American communities by building elevated highways through their neighborhoods. In order to build these elevated highways, the government destroyed tens of thousands of single-family homes. Because these properties were summarily declared to be "in decline," families were given pittances for their properties, and forced to move into federally-funded housing which was called "the projects". To build these projects, still more single family homes were demolished.[41]

President Woodrow Wilson did not oppose segregation practices by autonomous department heads of the federal Civil Service, according to Brian J. Cook in his work, Democracy And Administration: Woodrow Wilson's Ideas And The Challenges Of Public Management.[42] White and black people would sometimes be required to eat separately, go to separate schools, use separate public toilets, park benches, train, buses, and water fountains, etc. In some locales, in addition to segregated seating, it could be forbidden for stores or restaurants to serve different races under the same roof.

Public segregation was challenged by individual citizens on rare occasions but had minimal impact on civil rights issues, until December, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks refused to be moved to the back of a bus for a white passenger. Parks' civil disobedience had the effect of sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Parks' act of defiance became an important symbol of the modern Civil Rights Movement and Parks became an international icon of resistance to racial segregation.

Segregation was also pervasive in housing. State constitutions (for example, that of California) had clauses giving local jurisdictions the right to regulate where members of certain races could live. In 1917, the Supreme Court in the case of Buchanan v. Warley declared municipal resident segregation ordinances unconstitutional. In response, whites resorted to the restrictive covenant, a formal deed restriction binding white property owners in a given neighborhood not to sell to blacks. Whites who broke these agreements could be sued by "damaged" neighbors.[43] In the 1948 case of Shelley v. Kraemer, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled that such covenants were unenforceable in a court of law. However, residential segregation patterns had already become established in most American cities, and have often persisted up to the present from the impact of white flight and Redlining).

In most cities, the only way blacks could relieve the pressure of crowding that resulted from increasing migration was to expand residential borders into surrounding previously white neighborhoods, a process that often resulted in harassment and attacks by white residents whose intolerant attitudes were intensified by fears that black neighbors would cause property values to decline. Moreover, the increased presence of African Americans in cities, North and South, as well as their competition with whites for housing, jobs, and political influence sparked a series of race riots. In 1898 white citizens of Wilmington, North Carolina, resenting African Americans' involvement in local government and incensed by an editorial in an African-American newspaper accusing white women of loose sexual behavior, rioted and killed dozens of blacks. In the fury's wake, white supremacists overthrew the city government, expelling black and white office holders, and instituted restrictions to prevent blacks from voting. In Atlanta in 1906, newspaper accounts alleging attacks by black men on white women provoked an outburst of shooting and killing that left twelve blacks dead and seventy injured. An influx of unskilled black strikebreakers into East St Louis, Illinois, heightened racial tensions in 1917. Rumors that blacks were arming themselves for an attack on whites resulted in numerous attacks by white mobs on black neighborhoods. On July 1, blacks fired back at a car whose occupants they believed had shot into their homes and mistakenly killed two policemen riding in a car. The next day, a full scaled riot erupted which ended only after nine whites and thirty-nine blacks had been killed and over three hundred buildings were destroyed.

With the migration to the North of many black workers at the turn of the 20th century, and the friction that occurred between white and black workers during this time, segregation was and continues to be a phenomenon in northern cities as well as in the South. Whites generally allocate tenements as housing to the poorest blacks. It would be well to remember, though, that while racism had to be legislated out of the South, many in the North, including Quakers and others who ran the Underground Railroad, were ideologically opposed to Southerners' treatment of blacks. By the same token, many white Southerners have a claim to closer relationships with blacks than wealthy northern whites, regardless of the latter's stated political persuasion.[44]

Anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) prohibited whites and non-whites from marrying each other. These state laws always targeted marriage between whites and blacks, and in some states also prohibited marriages between whites and Native Americans or Asians. As one of many examples of such state laws, Utah's marriage law had an anti-miscegenation component that was passed in 1899 and repealed in 1963. It prohibited marriage between a white and anyone considered a Negro (Black American), mulatto (half black), quadroon (one-quarter black), octoroon (one-eighth black), "Mongolian" (East Asian), or member of the "Malay race" (a classification used to refer to Filipinos). No restrictions were placed on marriages between people who were not "white persons". (Utah Code, 40–1–2, C. L. 17, §2967 as amended by L. 39, C. 50; L. 41, Ch. 35.).

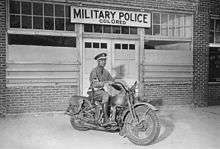

In World War I, blacks served in the United States Armed Forces in segregated units. Black soldiers were often poorly trained and equipped, and were often put on the frontlines in suicide missions. The 369th Infantry (formerly 15th New York National Guard) Regiment distinguished themselves, and were known as the "Harlem Hellfighters".[45][46]

The U.S. military was still heavily segregated in World War II. The Army Air Corps (forerunner of the Air Force) and the Marines had no blacks enlisted in their ranks. There were blacks in the Navy Seabees. The army had only five African-American officers.[47] In addition, no African American would receive the Medal of Honor during the war, and their tasks in the war were largely reserved to non-combat units. Black soldiers had to sometimes give up their seats in trains to the Nazi prisoners of war.[47] World War II saw the first black military pilots in the U.S., the Tuskegee Airmen, 99th Fighter Squadron,[48] and also saw the segregated 183rd Engineer Combat Battalion participate in the liberation of Jewish survivors at Buchenwald.[49] Despite the institutional policy of racially segregated training for enlisted members and in tactical units; Army policy dictated that black and white soldiers would train together in officer candidate schools (beginning in 1942).[50][51] Thus, the Officer Candidate School became the Army's first formal experiment with integration- with all Officer Candidates, regardless of race, living and training together.[51]

During World War II, 110,000 people of Japanese descent (whether citizens or not) were placed in internment camps. Hundreds of people of German and Italian descent were also imprisoned (see German American internment and Italian American internment). While the government program of Japanese American internment targeted all the Japanese in America as enemies, most German and Italian Americans were left in peace and were allowed to serve in the U.S. military.

Pressure to end racial segregation in the government grew among African Americans and progressives after the end of World War II. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, ending segregation in the United States Armed Forces.

A club central to the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, the Cotton Club in Harlem, New York City was a whites-only establishment, with blacks (such as Duke Ellington) allowed to perform, but to a white audience.[52] The first black Oscar recipient Hattie McDaniel was not permitted to attend the premiere of Gone with the Wind with Georgia being racially segregated, and at the Oscars ceremony at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles she was required to sit at a segregated table at the far wall of the room; the hotel had a no-blacks policy, but allowed McDaniel in as a favor.[53] On September 11, 1964, John Lennon announced The Beatles would not play to a segregated audience in Jacksonville, Florida.[54] City officials relented following this announcement.[54] A contract for a 1965 Beatles concert at the Cow Palace in California specifies that the band "not be required to perform in front of a segregated audience".[54]

Despite all the legal changes that have taken place since the 1940s and especially in the 1960s (see Desegregation), the United States remains, to some degree, a segregated society, with housing patterns, school enrollment, church membership, employment opportunities, and even college admissions all reflecting significant de facto segregation. Supporters of affirmative action argue that the persistence of such disparities reflects either racial discrimination or the persistence of its effects.

Gates v. Collier was a case decided in federal court that brought an end to the trusty system and flagrant inmate abuse at the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, Mississippi. In 1972 federal judge, William C. Keady found that Parchman Farm violated modern standards of decency. He ordered an immediate end to all unconstitutional conditions and practices. Racial segregation of inmates was abolished. And the trusty system, which allowed certain inmates to have power and control over others, was also abolished.[55]

More recently, the disparity between the racial compositions of inmates in the American prison system has led to concerns that the U.S. Justice system furthers a "new apartheid".[56]

Scientific

The intellectual root of Plessy v. Ferguson, the landmark United States Supreme Court decision upholding the constitutionality of racial segregation, under the doctrine of "separate but equal", was, in part, tied to the scientific racism of the era. However, the popular support for the decision was more likely a result of the racist beliefs held by most whites at the time.[57] Later, the court decision Brown v. Board of Education would reject the ideas of scientific racists about the need for segregation, especially in schools. Following that decision both scholarly and popular ideas of scientific racism played an important role in the attack and backlash that followed the court decision.[57]

The Mankind Quarterly is a journal that has published scientific racism. It was founded in 1960, partly in response to the 1954 United States Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, which ordered the desegregation of US schools.[58][59] Many of the publication's contributors, publishers, and Board of Directors espouse academic hereditarianism. The publication is widely criticized for its extremist politics, anti-semitic bent and its support for scientific racism.[60]

In the South

After the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops, which followed from the Compromise of 1877, the Democratic governments in the South instituted state laws to separate black and white racial groups, submitting African-Americans to de facto second-class citizenship and enforcing white supremacy. Collectively, these state laws were called the Jim Crow system, after the name of a stereotypical 1830s black minstrel show character.[61] Sometimes, as in Florida's Constitution of 1885, segregation was mandated by state constitutions.

Racial segregation became the law in most parts of the American South until the Civil Rights Movement. These laws, known as Jim Crow laws, forced segregation of facilities and services, prohibited intermarriage, and denied suffrage. Impacts included:

- Segregation of facilities included separate schools, hotels, bars, hospitals, toilets, parks, even telephone booths, and separate sections in libraries, cinemas, and restaurants, the latter often with separate ticket windows and counters.[62]

- Laws prohibited blacks from being present in certain locations. For example, blacks in 1939 were not allowed on the streets of Palm Beach, Florida after dark, unless required by their employment.[63]

- State laws prohibiting interracial marriage ("miscegenation") had been enforced throughout the South and in many Northern states since the Colonial era. During Reconstruction, such laws were repealed in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Texas and South Carolina. In all these states such laws were reinstated after the Democratic "Redeemers" came to power. The Supreme Court declared such laws constitutional in 1883. This verdict was overturned only in 1967 by Loving v. Virginia.[64]

- The voting rights of blacks were systematically restricted or denied through suffrage laws, such as the introduction of poll taxes and literacy tests. Loopholes, such as the grandfather clause and the understanding clause, protected the voting rights of white people who were unable to pay the tax or pass the literacy test. (See Senator Benjamin Tillman's open defense of this practice.) Only whites could vote in Democratic Party primary contests.[64] Where and when black people did manage to vote in numbers, their votes were negated by systematic gerrymander of electoral boundaries.

- In theory the segregated facilities available for negroes were of the same quality as those available to whites, under the separate but equal doctrine. In practice this was rarely the case. For example, in Martin County, Florida, students at Stuart Training School "read second-hand books...that were discarded from their all-white counterparts at Stuart High School. They also wore secondhand basketball and football uniforms.... The students and their parents built the basketball court and sidewalks at the school without the help of the school board. 'We even put in wiring for lights along the sidewalk, but the school board never connected the electricity.'"[65]

An African-American historian, Marvin Dunn, described segregation in Miami, Florida, around 1950:

My mother shopped there [Burdines Department Store] but she was not allowed to try on clothes or to return clothes. Blacks were not allowed to use the elevator or eat at the lunch counter. All the white stores were similar in this regard. The Greyhound Bus Station had separate waiting rooms and toilets for blacks and whites. Blacks could not eat at the counter in the bus station. The first black police officers for the city had been hired in 1947…but they could not arrest white people. My parents were registered as Republicans until the 1950s because they were not allowed to join the Democrat Party before 1947.[66]

In the North

Formal segregation also existed in the North. Some neighborhoods were restricted to blacks and job opportunities were denied them by unions in, for example, the skilled building trades. Blacks who moved to the North in the Great Migration after World War I sometimes could live without the same degree of oppression experienced in the South, but the racism and discrimination still existed.

Despite the actions of abolitionists, life for free blacks was far from idyllic, due to northern racism. Most free blacks lived in racial enclaves in the major cities of the North: New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati. There, poor living conditions led to disease and death. In a Philadelphia study in 1846, practically all poor black infants died shortly after birth. Even wealthy blacks were prohibited from living in white neighborhoods due to whites' fear of declining property values.[67]

While it is commonly thought that segregation was a Southern phenomenon, segregation was also to be found in "the North". The Chicago suburb of Cicero, for example, was made famous when Civil Rights advocate Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. led a march advocating open (race-unbiased) housing.

Northern blacks were forced to live in a white man's democracy, and while not legally enslaved, were subject to definition by their race. In their all-black communities, they continued to build their own churches and schools and to develop vigilance committees to protect members of the black community from hostility and violence.[67]

In the 1930s, however, job discrimination ended for many African Americans in the North, after the Congress of Industrial Organizations, one of America's lead labor unions at the time, agreed to integrate the union.[68]

School segregation in the North was also a major issue.[69] In Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, towns in the south of those states enforced school segregation, despite state laws outlawing the practice of it.[69] Indiana also required school segregation by state law.[69] During the 1940s, however, NAACP lawsuits quickly depleted segregation from the Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New Jersey southern areas.[69] In 1949, Indiana officially repealed its school segregation law as well.[69] The most common form of segregation in the northern states came from anti-miscegenation laws.[70]

The state of Oregon went farther than even any of the Southern states, specifically excluding blacks from entering the state, or from owning property within it. School integration did not come about until the Mid 1970s. As of 2017, the population of Oregon was about 2% black.[71][72]

Sports

Segregation in sports in the United States was also a major national issue.[73] In 1900, just four years after the US Supreme Court separate but equal constitutional ruling, segregation was enforced in horse racing, a sport which had previously seen many African American jockeys win Triple Crown and other major races.[74] Widespread segregation would also exist in bicycle and automobile racing.[74] In 1890, however, segregation would lessen for African-American track and field athletes after various universities and colleges in the northern states agreed to integrate their track and field teams.[74] Like track and field, soccer was another which experienced a low amount of segregation in the early days of segregation.[74] Many colleges and universities in the northern states would also allow African Americans on to play their football teams as well.[74]

Segregation was also hardly enforced in boxing.[74] In 1908, Jack Johnson, would become the first African American to win the World Heavyweight Title.[74] However, Johnson's personal life (i.e. his publicly acknowledged relationships with white women) made him very unpopular among many Caucasians throughout the world.[74] It was not until 1937, when Joe Louis defeated German boxer Max Schmeling, that the general American public would embrace, and greatly accept, an African American as the World Heavyweight Champion.[74]

In 1904, Charles Follis became the first African American to play for a professional football team, the Shelby Blues,[74] and professional football leagues agreed to allow only a limited number of teams to be integrated.[74] In 1933, however, the NFL, now the only major football league in the United States, reversed its limited integration policy and completely segregated the entire league.[74] However, the NFL color barrier would permanently break in 1946, when the Los Angeles Rams signed Kenny Washington and Woody Strode and the Cleveland Browns hired Marion Motley and Bill Wallis.[74]

Prior to the 1930s, basketball would also suffer a great deal of discrimination as well.[74] Black and whites played mostly in different leagues and usually were forbidden from playing in inter-racial games.[74] However, the popularity of the African American basketball team The Harlem Globetrotters would alter the American public's acceptance of African Americans in basketball.[74] By the end of the 1930s, many northern colleges and universities would allow African Americans to play on their teams.[74] In 1942, the color barrier for basketball was removed after Bill Jones and three other African American basketball players joined the Toledo Jim White Chevrolet NBL franchise and five Harlem Globetrotters joined the Chicago Studebakers.[74]

In 1947, segregation in professional sports would suffer a very big blow after the baseball color line was broken, when Negro Leagues baseball player Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and had a breakthrough season.[74]

By the end of 1949, however, only fifteen states had no segregation laws in effect.[70] and only eighteen states had outlawed segregation in public accommodations.[70] Of the remaining states, twenty still allowed school segregation to take place,[70] fourteen still allowed segregation to remain in public transportation[70] and 30 still enforced laws forbidding miscegenation.[70]

NCAA Division I has two historically black athletic conferences: Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (founded in 1970) and Southwestern Athletic Conference (founded in 1920). The Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (founded in 1912) and Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (founded in 1913) are part of the NCAA Division II, whereas the Gulf Coast Athletic Conference (founded in 1981) is part of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics Division I.

In 1948, the National Association for Intercollegiate Basketball became the first national organization to open their intercollegiate postseason to black student-athletes. In 1953, it became the first collegiate association to invite historically black colleges and universities into its membership.

Contemporary segregation

— Lionel Hampton on Benny Goodman,[75] who helped to launch the careers of many major names in jazz, and during an era of segregation, he also led one of the first racially integrated musical groups.

Black-White segregation is consistently declining for most metropolitan areas and cities, though there are geographical differences. In 2000, for instance, the US Census Bureau found that residential segregation has on average declined since 1980 in the West and South, but less so in the Northeast and Midwest.[76] Indeed, the top ten most segregated cities are in the Rust Belt, where total populations have declined in the last few decades.[77] Despite these pervasive patterns, changes for individual areas are sometimes small.[78] Thirty years after the civil rights era, the United States remains a residentially segregated society in which blacks and whites still often inhabit vastly different neighborhoods.[78][79]

Redlining is the practice of denying or increasing the cost of services, such as banking, insurance, access to jobs,[80] access to health care,[81] or even supermarkets[82] to residents in certain, often racially determined,[83] areas. The most devastating form of redlining, and the most common use of the term, refers to mortgage discrimination. Data on house prices and attitudes toward integration suggest that in the mid-20th century, segregation was a product of collective actions taken by whites to exclude blacks from their neighborhoods.[84]

The creation of expressways in some cases divided and isolated black neighborhoods from goods and services, many times within industrial corridors. For example, Birmingham's interstate highway system attempted to maintain the racial boundaries that had been established by the city's 1926 racial zoning law. The construction of interstate highways through black neighborhoods in the city led to significant population loss in those neighborhoods and is associated with an increase in neighborhood racial segregation.[85]

The desire of some whites to avoid having their children attend integrated schools has been a factor in white flight to the suburbs,[86] and in the foundation of numerous segregation academies and private schools which most African-American students, though technically permitted to attend, are unable to afford.[87] Recent studies in San Francisco showed that groups of homeowners tended to self-segregate to be with people of the same education level and race.[88] By 1990, the legal barriers enforcing segregation had been mostly replaced by indirect factors, including the phenomenon where whites pay more than blacks to live in predominantly white areas.[84] The residential and social segregation of whites from blacks in the United States creates a socialization process that limits whites' chances for developing meaningful relationships with blacks and other minorities. The segregation experienced by whites from blacks fosters segregated lifestyles and leads them to develop positive views about themselves and negative views about blacks.[89]

Segregation affects people from all social classes. For example, a survey conducted in 2000 found that middle-income, suburban Blacks live in neighborhoods with many more whites than do poor, inner-city blacks. But their neighborhoods are not the same as those of whites having the same socioeconomic characteristics; and, in particular, middle-class blacks tend to live with white neighbors who are less affluent than they are. While, in a significant sense, they are less segregated than poor blacks, race still powerfully shapes their residential options.[90]

The number of hypersegregated inner-cities is now beginning to decline. By reviewing census data, Rima Wilkes and John Iceland found that nine metropolitan areas that had been hypersegregated in 1990 were not by 2000.[91] Only two new cities, Atlanta and Mobile, Alabama, became hypersegregated over the same time span.[91] This points towards a trend of greater integration across most of the United States.

Residential segregation

Racial segregation is most pronounced in housing. Although in the U.S. people of different races may work together, they are still very unlikely to live in integrated neighborhoods. This pattern differs only by degree in different metropolitan areas.[93]

Residential segregation persists for a variety of reasons. Segregated neighborhoods may be reinforced by the practice of "steering" by real estate agents. This occurs when a real estate agent makes assumptions about where their client might like to live based on the color of their skin.[94] Housing discrimination may occur when landlords lie about the availability of housing based on the race of the applicant, or give different terms and conditions to the housing based on race; for example, requiring that black families pay a higher security deposit than white families.[95]

Redlining has helped preserve segregated living patterns for blacks and whites in the United States because discrimination motivated by prejudice is often contingent on the racial composition of neighborhoods where the loan is sought and the race of the applicant. Lending institutions have been shown to treat black mortgage applicants differently when buying homes in white neighborhoods than when buying homes in black neighborhoods in 1998.[96]

These discriminatory practices are illegal. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibits housing discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, or disability. The Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity is charged with administering and enforcing fair housing laws. Any person who believes that they have faced housing discrimination based on their race can file a fair housing complaint.[97]

Households were held back or limited to the money that could be made. Inequality was present in the workforce which lead over to the residential areas. This study provides this statistic of "The median household income of African Americans were 62 percent of non-Hispanic Whites ($27,910 vs. $44,504)"[98] However, blacks were forced by system to be in urban and poor areas while the whites lived together, being able to afford the more expensive homes. These forced measures promoted poverty levels to rise and belittle blacks.

Massey and Denton proposed that the fundamental cause of poverty among African Americans is segregation. This segregation has created the inner city black urban ghettos that create poverty traps and keep blacks from being able to escape the underclass. It is sometimes claimed that these neighborhoods have institutionalized an inner city black culture that is negatively stigmatized and purports the economic situation of the black community. Sociolinguist, William Labov[99] argues that persistent segregation supports the use of African American English (AAE) while endangering its speakers. Although AAE is stigmatized, sociolinguists who study it note that it is a legitimate dialect of English as systematic as any other.[100] Arthur Spears argues that there is no inherent educational disadvantage in speaking AAE and that it exists in vernacular and more standard forms.[101]

Historically, residential segregation split communities between the black inner city and white suburbs. This phenomenon is due to white flight where whites actively leave neighborhoods often because of a black presence. There are more than just geographical consequences to this, as the money leaves and poverty grows, crime rates jump and businesses leave and follow the money. This creates a job shortage in segregated neighborhoods and perpetuates the economic inequality in the inner city. With the wealth and businesses gone from inner city areas, the tax base decreases, which hurts funding for education. Consequently, those that can afford to leave the area for better schools leave decreasing the tax base for educational funding even more. Any business that is left or would consider opening doesn't want to invest in a place nobody has any money but has a lot of crime, meaning the only things that are left in these communities are poor black people with little opportunity for employment or education."[102]

Today, a number of whites are willing, and are able, to pay a premium to live in a predominantly white neighborhood. Equivalent housing in white areas commands a higher rent.[103] By bidding up the price of housing, many white neighborhoods again effectively shut out blacks, because blacks are unwilling, or unable, to pay the premium to buy entry into white neighborhoods. While some scholars maintain that residential segregation has continued—some sociologists have termed it "hypersegregation" or "American Apartheid"[104]—the US Census Bureau has shown that residential segregation has been in overall decline since 1980.[105] According to a 2012 study found that "credit markets enabled a substantial fraction of Hispanic families to live in neighborhoods with fewer black families, even though a substantial fraction of black families were moving to more racially integrated areas. The net effect is that credit markets increased racial segregation."[106]

As of 2015, residential segregation had taken new forms in the United States with black majority minority suburbs such as Ferguson, Missouri, supplanting the historic model of black inner cities, white suburbs.[107] Meanwhile, in locations such as Washington, D.C., gentrification had resulted in development of new white neighborhoods in historically black inner cities. Segregation occurs through premium pricing by white people of housing in white neighborhoods and exclusion of low-income housing[108] rather than through rules which enforce segregation. Black segregation is most pronounced; Hispanic segregation less so, and Asian segregation the least.[109][110]

Commercial and industrial segregation

Lila Ammons discusses the process of establishing black-owned banks during the 1880s-1990s, as a method of dealing with the discriminatory practices of financial institutions against African-American citizens of the United States. Within this period, she describes five distinct periods that illustrate the developmental process of establishing these banks, which were as followed:

1888–1928

In 1851, one of the first meetings to begin the process of establishing black-owned banks took place, although the ideas and implementation of these ideas were not utilized until 1888.[111] During this period, approximately 60 black-owned banks were created, which gave blacks the ability to access loans and other banking needs, which non-minority banks would not offer African-Americans.

1929–1953

Only five banks were opened during this time, while seeing many black-owned banks closed, leaving these banks with an expected nine-year life span for their operations.[112] With African-Americans continuing to migrate towards Northern urban areas, they were faced with the challenge of suffering from high unemployment rates, due to non-minorities willing to do work that African Americans would previously take part in.[113] At this time the entire banking industry, in the U.S., was suffering however, these banks suffered even more due to being smaller, having higher closure rates, as well as lower rates of loan repayment. The first groups of banks invested their finances back into the Black community, where as banks established during this period invested their finances mainly in mortgage loans, fraternal societies, and U.S. government bonds.[114]

1954–1969

Approximately 20 more banks were established during this period, which also saw African Americans become active citizens by taking part in various social movements centered around economic equality, better housing, better jobs, and the desegregation of society.[115] Through desegregation however, these banks could no longer solely depend on the Black community for business and were forced to become established on the open market, by paying their employees competitive wages, and were now required to meet the needs of the entire society instead of just the Black community.[115]

1970–1979

Urban deindustrialization was occurring, resulting in the number of black-owned banks being increased considerably, with 35 banks established, during this time.[116] Although this change in economy allowed more banks to be opened, this period further crippled the African-American community, as unemployment rates raised more with the shift in the labour market, from unskilled labour to government jobs.[117]

1980–1990s

Approximately 20 banks were established during this time, however all banks were competing with other financial institutions that serve the financial necessities of people at a lower cost.[118]

2000s

Dan Immergluck writes that in 2003 small businesses in black neighborhoods still received fewer loans, even after accounting for business density, business size, industrial mix, neighborhood income, and the credit quality of local businesses.[119] Gregory D. Squires wrote in 2003 that it is clear that race has long affected and continues to affect the policies and practices of the insurance industry.[120] Workers living in American inner-cities have a harder time finding jobs than suburban workers, a factor that disproportionately affects black workers.[121]

Rich Benjamin's book, Searching for Whitopia: An Improbable Journey to the Heart of White America, reveals the state of residential, educational, and social segregation. In analyzing racial and class segregation, the book documents the migration of white Americans from urban centers to small-town, exurban, and rural communities. Throughout the 20th Century, racial discrimination was deliberate and intentional. Today, racial segregation and division result from policies and institutions that are no longer explicitly designed to discriminate. Yet the outcomes of those policies and beliefs have negative, racial impacts, namely with segregation.[122]

Transportation segregation

Local bus companies practiced segregation in city buses. This was challenged in Montgomery, Alabama by Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat to a white passenger, and by Rev. Martin Luther King, who organized the Montgomery bus boycott (1955–1956). A federal court suit in Alabama, Browder v. Gayle (1956), was successful at the district court level, which ruled Alabama's bus segregation laws illegal. It was upheld at the Supreme Court level.

In 1961 Congress of Racial Equality director James Farmer, other CORE members and some Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee members traveled as a mixed race group, Freedom Riders, on Greyhound buses from Washington, D.C., headed towards New Orleans. In several states the travelers were subject to violence. In Anniston, Alabama the Ku Klux Klan attacked the buses, setting one bus on fire. After U.S. attorney general Robert F. Kennedy resisted taking action and urged restraint by the riders, Kennedy relented. He urged the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue an order directing that buses, trains, and their intermediate facilities, such as stations, restrooms and water fountains be desegregated.[123][124]

Effects

Education

Segregation in education has major social repercussions. The prejudice that many young African-Americans experience causes them undue stress which has been proven to undermine cognitive development. Eric Hanushek and his co-authors have considered racial concentrations in schools, and they find large and important effects. Black students appear to be systematically and physically hurt by larger concentrations of black students in their school. These effects extend neither to white nor to Hispanic students in the school, implying that they are related to peer interactions and not to school quality.[125] Moreover, it appears that the effect of black concentrations in schools is largest for high-achieving black students.[126]

Even African Americans from poor inner-cities who do attend universities continue to suffer academically due to the stress they suffer from having family and friends still in the poverty-stricken inner cities.[127] Education is also used as a means to perpetuate hypersegregation. Real estate agents often implicitly use school racial composition as a way of enticing white buyers into the segregated ring surrounding the inner-city[128]

The percentage of black children who now go to integrated public schools is at its lowest level since 1968.[129] The words of "American apartheid" have been used in reference to the disparity between white and black schools in America. Those who compare this inequality to apartheid frequently point to unequal funding for predominantly black schools.[130]

In Chicago, by the academic year 2002–2003, 87 percent of public-school enrollment was black or Hispanic; less than 10 percent of children in the schools were white. In Washington, D.C., 94 percent of children were black or Hispanic; less than 5 percent were white.

Jonathan Kozol expanded on this topic in his book The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America.

The "New American apartheid" refers to the allegation that US drug and criminal policies in practice target blacks on the basis of race. The radical left-wing web-magazine ZNet featured a series of 4 articles on "The New American Apartheid" in which it drew parallels between the treatment of blacks by the American justice system and apartheid:

Modern prisoners occupy the lowest rungs on the social class ladder, and they always have. The modern prison system (along with local jails) is a collection of ghettos or poorhouses reserved primarily for the unskilled, the uneducated, and the powerless. In increasing numbers this system is being reserved for racial minorities, especially blacks, which is why we are calling it the New American Apartheid. This is the same segment of American society that has experienced some of the most drastic reductions in income and they have been targeted for their involvement in drugs and the subsequent violence that extends from the lack of legitimate means of goal attainment.[131]

This article has been discussed at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice and by several school boards attempting to address the issue of continued segregation.

In higher education, some disadvantaged groups now demand segregated academic and social enclaves, including dormitories, orientation sessions, and commencement ceremonies. This serves the purpose of making students of color more comfortable and highlighting the challenges they face on historically white-dominated campuses, although it may impair the ability of such students to interact with people outside of their specific group.[132]

Due to education being funded primarily through local and state revenue, the quality of education varies greatly depending on the geographical location of the school. In some areas, education is primarily funded through revenue from property taxes; therefore, there is a direct correlation in some areas between the price of homes and the amount of money allocated to educating the area's youth.[133] A 2010 US Census showed that 27.4% of all African-Americans lived under the poverty line, the highest percentage of any other ethnic group in the United States.[134] Therefore, in predominantly African-American areas, otherwise known as 'ghettos', the amount of money available for education is extremely low. This is referred to as "funding segregation".[133] This questionable system of educational funding can be seen as one of the primary reasons contemporary racial segregation continues to prosper. Predominantly Caucasian areas with more money funneled into primary and secondary educational institutions, allow their students the resources to succeed academically and obtain post-secondary degrees. This practice continues to ethnically, socially and economically divide America.

Alternative certificate programs were introduced in many inner-city schools and rural areas. These programs award a person a teaching license even though he/she has not completed a traditional teaching degree. This program came into effect in the 1980s throughout most states in response to the dwindling number of people seeking to earn a secondary degree in education.[135] This program has been very controversial. It is, "booming despite little more than anecdotal evidence of their success.[…] there are concerns about how they will perform as teachers, especially since they are more likely to end up in poor districts teaching students in challenging situations."[136] Alternative Certificate graduates tend to teach African-Americans and other ethnic minorities in inner-city schools and schools in impoverished small rural towns. Therefore, impoverished minorities not only have to cope with having the smallest amount of resources for their educational facilities but also with having the least trained teachers in the nation. Valorie Delp, a mother residing in an inner-city area whose child attends a school taught by teachers awarded by an alternative certificate program notes:

One teacher we know who is in this program said he had visions of coming in to "save" the kids and the school and he really believes that this idea was kind of stoked in his program. No one ever says that you may have kids who threaten to stab you, or call you unspeakable names to your face, or can't read despite being in 7th grade.[137]

Delp showcases that, while many graduates of these certificate programs have honorable intentions and are educated, intelligent people, there is a reason why teachers have traditionally had to take a significant amount of training before officially being certified as a teacher. The experience they gain through their practicum and extensive classroom experience equips them with the tools necessary to educate today's youth.

Some measures have been taken to try give less affluent families the ability to educate their children. President Ronald Reagan introduced the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act on July 22, 1987.[138] This Act was meant to allow children the ability to succeed if their families did not have a permanent residence. Leo Stagman, a single, African-American parent, located in Berkeley, California, whose daughter had received a great deal of aid from the Act wrote on October 20, 2012 that, "During her education, she [Leo's daughter] was eligible for the free lunch program and received assistance under the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Educational Act. I know my daughter's performance is hers, but I wonder where she would have been without the assistance she received under the McKinney-Vento Act. Many students at BHS owe their graduation and success to the assistance under this law."[139]

Leo then goes on to note that, "the majority of the students receiving assistance under the act are Black and Brown."[139] There have been various other Acts enacted to try and aid impoverished youth with the chance to succeed. One of these Acts includes the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB). This Act was meant to increase the accountability of public schools and their teachers by creating standardized testing which would give an overview of the success of the school's ability to educate their students.[140] Schools which repeatedly performed poorly would have increased attention and assistance from the federal government.[140] One of the intended outcomes of the Act was to narrow the class and racial achievement gap in the United States by instituting common expectations for all students.[140] Test scores have shown to be improving for minority populations, however, they are improving at the same rate for Caucasian children as well. This Act therefore, has done little to close the educational gap between Caucasian and minority children.[141]

There has also been an issue with minority populations becoming educated because to a fear of being accused of "Acting White". It is a hard definition to pin down, however, this is a negative term predominantly used by African-Americans that showing interest in one's studies is a betrayal of the African-American culture as one is trying to be a part of white society rather than staying true to his/her roots. Roland G. Fryer, Jr., at Harvard University has noted that, "There is necessarily a trade-off between doing well and rejection by your peers when you come from a traditionally low-achieving group, especially when that group comes into contact with more outsiders."[142] Therefore, not only are there economic and prehistoric causes of racial educational segregation, but there are also social notions that continue to be obstacles to be overcome before minority groups can achieve success in education.

Mississippi is one of the US states where some public schools still remain highly segregated just like the 1960s when discrimination against black people was very rampant.[143] In many communities where black kids represent the majority, white children are the only ones who enroll in small private schools. The University of Mississippi, the state’s flagship academic institution enrolls unreasonably few African-American and Latino young people. These schools are supposed to stand for excellence in terms of education and graduation but the opposite is happening.[144] Private schools located in Jackson City including small towns are populated by large numbers of white students. Continuing school segregation exists in Mississippi, South Carolina, and other communities where whites are separated from blacks.[145]

Segregation is not limited to areas in the Deep South but places like New York as well. The state was more segregated for black students compared to any other Southern state. There is a case of double segregation because students have become isolated both by race and household income. In New York City, 19 out of 32 school districts have fewer white students.[146] The United States Supreme Court tried to deal with school segregation more than six decades ago but impoverished and colored students still do not have equal access to opportunities in education.[147] In spite of this situation, the Government Accountability office circulated a 108-page report that showed from 2000 up to 2014, the percentage of deprived black or Hispanic students in American K-12 public schools increased from nine to 16 percent.[148]

Health

Another impact of hypersegregation can be found in the health of the residents of certain areas. Poorer inner-cities often lack the health care that is available in outside areas. That many inner-cities are so isolated from other parts of society also is a large contributor to the poor health often found in inner-city residents. The overcrowded living conditions in the inner-city caused by hypersegregation means that the spread of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, occurs much more frequently.[149] This is known as "epidemic injustice" because racial groups confined in a certain area are affected much more often than those living outside the area.

Poor inner-city residents also must contend with other factors that negatively affect health. Research has proven that in every major American city, hypersegregated blacks are far more likely to be exposed to dangerous levels of air toxins.[150] Daily exposure to this polluted air means that African-Americans living in these areas are at greater risk of disease.

Crime

One area where hypersegregation seems to have the greatest effect is in violence experienced by residents. The number of violent crimes in the U.S. in general has fallen. The number of murders in the U.S. fell 9% from the 1980s to the 1990s.[151] Despite this number, the crime rates in the hypersegregated inner-cities of America continued to rise. As of 1993, young African-American men are eleven times more likely to be shot to death and nine times more likely to be murdered than their European American peers.[104] Poverty, high unemployment, and broken families, all factors more prevalent in hypersegregated inner-cities, all contribute significantly to the unequal levels of violence experienced by African-Americans. Research has proven that the more segregated the surrounding European American suburban ring is, the rate of violent crime in the inner-city will rise, but, likewise, crime in the outer area will drop.[151]

Poverty

One study finds that an area's residential racial segregation increases metropolitan rates of black poverty and overall black-white income disparities, while decreasing rates of white poverty and inequality within the white population.[152]

Single parenthood

One study finds that African-Americans who live in segregated metro areas have a higher likelihood of single-parenthood than Blacks who live in more integrated places.[153]

Public spending

Research shows that segregation along racial lines contributes to public goods inequalities. Whites and blacks are vastly more likely to support different candidates for mayor than whites and blacks in more integrated places, which makes them less able to build consensus. The lack of consensus leads to lower levels of public spending.[154]

Costs

In April 2017, the Metropolitan Planning Council in Chicago and the Urban Institute, a think-tank located in Washington, DC, released a study estimating that racial and economic segregation is costing the United States billions of dollars every year. Statistics (1990–2010) from at least 100 urban hubs were analyzed. This report reported that segregation affecting Blacks economically was associated with higher rates of homicide.[155]

See also

- American Ghettos

- African-American history

- Civil rights movement (1865–1896)

- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- Civil rights movement

- Apartheid

- Auto-segregation

- Baseball color line

- Black Belt (region of Chicago)

- Black flight

- Black Lives Matter

- Black nationalism

- Black Power

- Black separatism

- Black supremacy

- Desegregation

- Ethnopluralism

- Housing Segregation

- Judicial aspects of race in the United States

- Laissez-Faire Racism

- List of anti-discrimination acts

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Nadir of American race relations

- Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- Race and health

- Race and longevity

- Racial integration

- Racial segregation

- Racial segregation in Atlanta

- Racial tension in Omaha, Nebraska

- Racism against African Americans in the U.S. military

- Racism in the United States

- Second-class citizen

- Segregated prom

- Separate but equal

- St. Augustine movement

- Timeline of racial tension in Omaha, Nebraska

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

References

- C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (3rd ed. 1947).

- Harvard Sitkoff, The Struggle for Black Equality (2008)

- Leon Litwack, Jim Crow Blues, Magazine of History (OAH Publications, 2004)

- "Barack Obama legacy: Did he improve US race relations?". BBC. Retrieved June 5, 2020

- Margo, Robert A. (1990). Race and Schooling in the South, 1880–1950: An Economic History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-226-50510-7.

- "Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1)". Oyez. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States". Oyez. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "The Court's Decision - Separate Is Not Equal". americanhistory.si.edu. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. A National Struggle . The Supreme Court | PBS". www.thirteen.org. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Judy L. Hasday, The Civil Rights Act of 1964: An End to Racial Segregation (2007).

- Krysan, Maria; Crowder, Kyle (2017). Cycle of Segregation: Social Processes and Residential Stratification. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-0871544902.

- Lee, Russell (July 1939). "Negro drinking at "Colored" water cooler in streetcar terminal, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma". Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Library of Congress Home. Retrieved March 23, 2005.

- Barbara J. Fields (1982). "Ideology and Race in American History". In J. Morgan Kousser; James M. McPherson (eds.). Region, Race, and Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of C. Vann Woodward. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-19-503075-4.

- Richard Zuczek (2015). Reconstruction: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic. ABC-CLIO. p. 172. ISBN 9781610699181.

- Berea College in Kentucky was the main exception until state law in 1904 forced its segregation. Heckman, Richard Allen; Hall, Betty Jean (1968). "Berea College and the Day Law". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 66 (1): 35–52. JSTOR 23376786.

- Annual Report: Hampton Negro Conference. 1901. p. 59.

- Joe M. Richardson, Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861–1890 (1986).

- C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (3rd ed. 1974)

- Casdorph, Paul D. (June 15, 2010). "Lily-White Movement". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- Armstead L. Robinson (2005). "Full of Faith, Full of Hope: African-American Experience From Emancipation to Segregation". In William R. Scott; William G. Shade (eds.). African-American Reader: Essays On African-American History, Culture, and Society. Washington: U.S. Department of State. pp. 105–123. OCLC 255903231.

- Marion Post Wolcott (October 1939). "Negro going in colored entrance of movie house on Saturday afternoon, Belzoni, Mississippi Delta, Mississippi". Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Library of Congress Home. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 540 (1896) (quoting the Louisiana statute). From Findlaw. Retrieved on December 30, 2012.

- "Jim Crow's Schools". American Federation of Teachers. August 8, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- Roback, Jennifer (1986). "The Political Economy of Segregation: The Case of Segregated Streetcars". Journal of Economic History. 56 (4): 893–917. doi:10.1017/S0022050700050634.

- Cumming v. Board of Education, 175 U.S. 528 (1899); Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908); Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927); Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938); Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950)

- Charles L. Lumpkins (2008). American Pogrom: The East St. Louis Race Riot and Black Politics. Ohio UP. p. 179. ISBN 9780821418031.

- Cheryl Lynn Greenberg (2009). To Ask for an Equal Chance: African Americans in the Great Depression. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 60. ISBN 9781442200517.

- Anthony J. Badger (2011). New Deal / New South: An Anthony J. Badger Reader. U. of Arkansas Press. p. 38. ISBN 9781610752770.

- Kay Rippelmeyer (2015). The Civilian Conservation Corps in Southern Illinois, 1933–1942. Southern Illinois Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9780809333653.

- Philip A. Klinkner; Rogers M. Smith (2002). The Unsteady March: The Rise and Decline of Racial Equality in America. U of Chicago Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780226443416.

- Harold Ickes, The secret diary of Harold L. Ickes Vol. 2: The inside struggle, 1936–1939 (1954) p 115

- David L. Chappell (2009). A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow. pp. 9–11. ISBN 9780807895573.

- Vincent N. Parrillo (2008). Encyclopedia of Social Problems. SAGE Publications. p. 508. ISBN 9781412941655.

- Dudley L. Poston; Michael Micklin (2006). Handbook of Population. Springer. p. 499. ISBN 9780387257020.

- Douglas S. Massey; Nancy A. Denton (August 1989). "Hypersegregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas: Black and Hispanic Segregation Along Five Dimensions". Demography. 26 (3): 373–391. doi:10.2307/2061599. ISSN 0070-3370. JSTOR 2061599. OCLC 486395765. S2CID 37301240.

- Charles E. Hurst (2007). Social Inequality: Forms, causes, and consequences (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-205-69829-5.

- David R Williams; Chiquita Collins. "Racial Residential Segregation: A Fundamental Cause of Racial Disparities in Health". Public Health Reports. 116 (5): 404–416. ISSN 0033-3549.

- Rima Wilkes; John Iceland (2004). "Hypersegregation in the Twenty First Century". Demography. 41 (1): 23–361. doi:10.1353/dem.2004.0009. JSTOR 1515211. OCLC 486373184. PMID 15074123. S2CID 5777361.

- "Here's Why Big Banks Are Lending to Fewer Blacks and Hispanics". Fortune. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "The Great Depression and the New Deal". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "When a City Turns White, What Happens to Its Black History?". historynewsnetwork.org. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Another Open Letter to Woodrow Wilson W.E.B. DuBois, September, 1913". Teachingamericanhistory.org. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- The Great Migration, Period: 1920s Archived January 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- History of Residential Segregation Archived November 14, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- "Detached Service By Segregated Infantry Units". Worldwar1.com. April 16, 1918. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- "James Reese Europe and The Harlem Hellfighters Band by Glenn Watkins". Worldwar1.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Foner, Eric (February 1, 2012). Give Me Liberty!: An American History (3 ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 696. ISBN 978-0393935530.

- "On Clipped Wings". May 9, 2006. Archived from the original on November 28, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "William A. Scott, III and the Holocaust: The Encounter of African American Liberators and Jewish Survivors at Buchenwald by Asa R. Gordon, Executive Director, Douglass Institute of Government". Asagordon.byethost10.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- morden, Bettie J. (2000) [1990]. "Chapter I The Women's Army Corps, 1942–1945". Women's Army Corps. Army Historical Series. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 30-14. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010.

- MacGregor Jr., Morris J. (1985). "CHAPTER 2 "World War II: The Army"". Integration of the Armed Forces: 1940–1965. Defense Studies Series. United States Army Center of Military History. (link: IAF-fm.htm).

- Ella Fitzgerald. Holloway House Publishing. 1989. p. 27.

- Abramovitch, Seth (February 19, 2015). "Oscar's First Black Winner Accepted Her Honor in a Segregated 'No Blacks' Hotel in L.A." The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- "The Beatles banned segregated audiences, contract shows". BBC. Retrieved July 17, 2017

- "Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice". Archived from the original on August 26, 2006. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- "The New American Apartheid". ZMag.org. June 22, 2004. Archived from the original on July 4, 2004. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Sarat, Austin (1997). Race, Law, and Culture: Reflections on Brown V. Board of Education. pp. 55 and 59. ISBN 978-0-19-510622-0.

- Schaffer, Gavin (2007). "'"Scientific" Racism Again?': Reginald Gates, the Mankind Quarterly and the Question of 'Race' in Science after the Second World War". Journal of American Studies. 41 (2): 253–278. doi:10.1017/S0021875807003477.

- Jackson, John P. (August 2005). Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case Against Brown V. Board of Education. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8147-4271-6.

- e.g., Arvidsson, Stefan (2006). Aryan Idols: Indo-European Mythology as Ideology and Science. translated by Sonia Wichmann. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-02860-6.

- Remembering Jim Crow – Minnesota Public Radio

- ""Jim Crow" Laws". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 229

- The History of Jim Crow Archived June 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Students remember receiving hand-me-down books, uniforms". Palm Beach Post (West Palm Beach, Florida). January 16, 2000. p. 27.

- Dunn, Marvin (2016). A History of Florida Through Black Eyes. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 225. ISBN 978-1519372673.

- "Africans in America" – PBS Series – Part 4 (2007)

- Brueggemann, John; Boswell, Terry (1998). "Realizing Solidarity: Sources of Interracial Unionism During the Great Depression". Work and Occupations. 25 (4): 436–482. doi:10.1177/0730888498025004003.

- "Q&A with Douglas: Northern segregation | University Relations". Web.wm.edu. December 13, 2005. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Falck, Susan. "Jim Crow Legislation Overview". Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- "Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon". Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- "Blacks in Oregon". Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- http://www.jimcrowhistory.org/geography/sports.htm Archived March 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- West, Jean M. "Jim Crow and Sports". The History of Jim Crow. Archived from the original on October 19, 2002.

- "Ibid"; Firestone, Ross pp. 183–184.

- "p. 72" (PDF). Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- "64, 72" (PDF). Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Sethi, Rajiv; Somanathan, Rohini (2004). "Inequality and Segregation". Journal of Political Economy. 112 (6): 1296–1321. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1029.4552. doi:10.1086/424742.

- Douglas S. Massey (August 2004). "Segregation and Strafication: A Biosocial Perspective". Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 1 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1017/S1742058X04040032.

- "Racial Discrimination and Redlining in Cities" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- See: Race and health

- Eisenhauer, Elizabeth (2001). "In poor health: Supermarket redlining and urban nutrition". GeoJournal. 53 (2): 125–133. doi:10.1023/A:1015772503007. S2CID 151164815.

- Thabit, Walter (2003). How East New York Became a Ghetto. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8147-8267-5.

- Cutler, David M.; Glaeser, Edward L.; Vigdor, Jacob L. (1999). "The Rise and Decline of the American Ghetto". Journal of Political Economy. 107 (3): 455–506. doi:10.1086/250069. S2CID 134413201.

- Connerly, Charles E. (2002). "From Racial Zoning to Community Empowerment: The Interstate Highway System and the African American Community in Birmingham, Alabama". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 22 (2): 99–114. doi:10.1177/0739456X02238441.

- Segregation in the United States – MSN Encarta Archived April 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Glenda Alice Rabby, The Pain and the Promise: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Tallahassee, Florida, Athens, Ga., University of Georgia Press, 1999, ISBN 082032051X, p. 255.

- Ap news article

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo; Embrick, David G. (2007). "'Every Place Has a Ghetto...': The Significance of Whites' Social and Residential Segregation". Symbolic Interaction. 30 (3): 323–345. doi:10.1525/si.2007.30.3.323.