List of Chinese inventions

|

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

| By subject |

| By era |

China has been the source of many innovations, scientific discoveries and inventions.[1] This includes the Four Great Inventions: papermaking, the compass, gunpowder, and printing (both woodblock and movable type). The list below contains these and other inventions in China attested by archaeological or historical evidence.

The historical region now known as China experienced a history involving mechanics, hydraulics and mathematics applied to horology, metallurgy, astronomy, agriculture, engineering, music theory, craftsmanship, naval architecture and warfare. By the Warring States period (403–221 BC), inhabitants of the Warring States had advanced metallurgic technology, including the blast furnace and cupola furnace, while the finery forge and puddling process were known by the Han Dynasty (202 BC–AD 220). A sophisticated economic system in imperial China gave birth to inventions such as paper money during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). The invention of gunpowder during the mid 9th century led to an array of inventions such as the fire lance, land mine, naval mine, hand cannon, exploding cannonballs, multistage rocket and rocket bombs with aerodynamic wings and explosive payloads. With the navigational aid of the 11th century compass and ability to steer at high sea with the 1st century sternpost rudder, premodern Chinese sailors sailed as far as East Africa.[2][3][4] In water-powered clockworks, the premodern Chinese had used the escapement mechanism since the 8th century and the endless power-transmitting chain drive in the 11th century. They also made large mechanical puppet theaters driven by waterwheels and carriage wheels and wine-serving automatons driven by paddle wheel boats.

The contemporaneous Peiligang and Pengtoushan cultures represent the oldest Neolithic cultures of China and were formed around 7000 BC.[5] Some of the first inventions of Neolithic China include semilunar and rectangular stone knives, stone hoes and spades, the cultivation of millet, rice, and the soybean, the refinement of sericulture, the building of rammed earth structures with lime-plastered house floors, the creation of pottery with cord-mat-basket designs, the creation of pottery tripods and pottery steamers and the development of ceremonial vessels and scapulimancy for purposes of divination.[6][7] The British sinologist Francesca Bray argues that the domestication of the ox and buffalo during the Longshan culture (c. 3000–c. 2000 BC) period, the absence of Longshan-era irrigation or high-yield crops, full evidence of Longshan cultivation of dry-land cereal crops which gave high yields "only when the soil was carefully cultivated," suggest that the plough was known at least by the Longshan culture period and explains the high agricultural production yields which allowed the rise of Chinese civilization during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–c. 1050 BC).[8] Later inventions such as the multiple-tube seed drill and heavy moldboard iron plough enabled China to sustain a much larger population through greater improvements in agricultural output.

For the purposes of this list, inventions are regarded as technological firsts developed in China, and as such does not include foreign technologies which the Chinese acquired through contact, such as the windmill from the Middle East or the telescope from early modern Europe. It also does not include technologies developed elsewhere and later invented separately by the Chinese, such as the odometer, water wheel, and chain pump. Scientific, mathematical or natural discoveries, changes in minor concepts of design or style and artistic innovations do not appear on the list.

Four Great Inventions

The following is a list of the Four Great Inventions—as designated by Joseph Needham (1900–1995), a British scientist, author and sinologist known for his research on the history of Chinese science and technology.[9]

Paper

- This sub-section is about paper making; for the writing material first used in ancient Egypt, see papyrus.

Although it is recorded that the Han Dynasty (202 BC – AD 220) court eunuch Cai Lun (50 AD – AD 121) invented the pulp papermaking process and established the use of new materials used in making paper, ancient padding and wrapping paper artifacts dating to the 2nd century BC have been found in China, the oldest example of pulp papermaking being a map from Fangmatan, Tianshui;[10] by the 3rd century, paper as a writing medium was in widespread use, replacing traditional but more expensive writing mediums such as strips of bamboo rolled into threaded scrolls, strips of silk, wet clay tablets hardened later in a furnace, and wooden tablets.[11][12][13][14][15] The earliest known piece of paper with writing on it was discovered in the ruins of a Chinese watchtower at Tsakhortei, Alxa League, where Han Dynasty troops had deserted their position in AD 110 following a Xiongnu attack.[16] In the paper making process established by Cai in 105, a boiled mixture of mulberry tree bark, hemp, old linens and fish nets created a pulp that was pounded into paste and stirred with water; a wooden frame sieve with a mat of sewn reeds was then dunked into the mixture, which was then shaken and then dried into sheets of paper that were bleached under the exposure of sunlight; K.S. Tom says this process was gradually improved through leaching, polishing and glazing to produce a smooth, strong paper.[13][14]

Printing

- For the separate invention of movable type printing in medieval Europe, see printing press and Johannes Gutenberg.

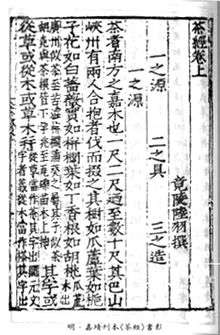

Woodblock printing: The earliest specimen of woodblock printing is a single-sheet dharani sutra in Sanskrit that was printed on hemp paper between 650 and 670 AD; it was unearthed in 1974 from a Tang tomb near Xi'an.[17] A Korean miniature dharani Buddhist sutra discovered in 1966, bearing extinct Chinese writing characters used only during the reign of China's only self-ruling empress, Wu Zetian (r.690–705), is dated no earlier than 704 and preserved in a Silla Korean temple stupa built in 751.[18] The first printed periodical, the Kaiyuan Za Bao was made available in AD 713. However, the earliest known book printed at regular size is the Diamond Sutra made during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), a 5.18 m (17 ft) long scroll which bears the date 868 AD.[19] Joseph Needham and Tsien Tsuen-hsuin write that the cutting and printing techniques used for the delicate calligraphy of the Diamond Sutra book are much more advanced and refined than the miniature dharani sutra printed earlier.[19]

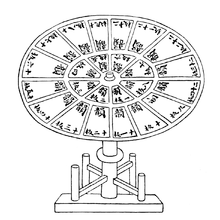

Movable type: The polymath scientist and official Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song Dynasty (960–1279) was the first to describe the process of movable type printing in his Dream Pool Essays of 1088. He attributed the innovation of reusable fired clay characters to a little-known artisan named Bi Sheng (990–1051).[20][21][22][23] Bi had experimented with wooden type characters, but their use was not perfected until 1297 to 1298 with the model of the official Wang Zhen (fl. 1290–1333) of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), who also arranged written characters by rhyme scheme on the surface of round table compartments.[21][24] It was not until 1490 with the printed works of Hua Sui (1439–1513) of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) that the Chinese perfected metal movable type characters, namely bronze.[25][26] The Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) scholar Xu Zhiding of Tai'an, Shandong developed vitreous enamel movable type printing in 1718.[27]

Gunpowder

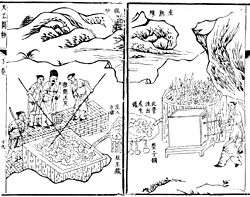

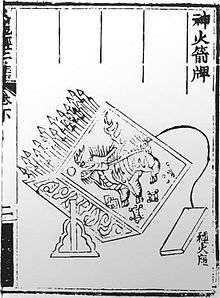

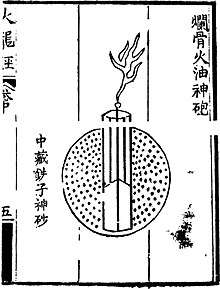

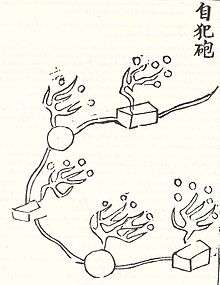

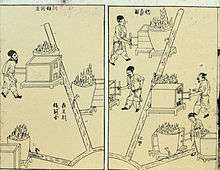

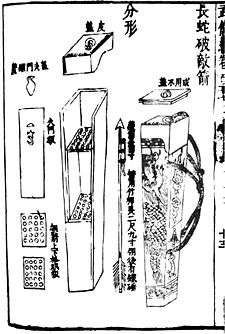

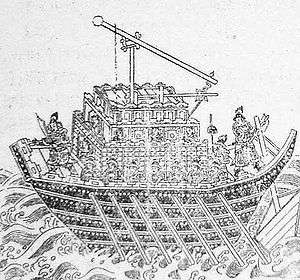

Evidence of gunpowder's first use in China comes from the Tang dynasty (618–907).[28] The earliest known recorded recipes for gunpowder were written by Zeng Gongliang, Ding Du and Yang Weide in the Wujing Zongyao, a military manuscript compiled in 1044 during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Its gunpowder formulas describe the use of incendiary bombs launched from catapults, thrown down from defensive walls, or lowered down the wall by use of iron chains operated by a swape lever.[29][30][31] Bombs launched from trebuchet catapults mounted on forecastles of naval ships ensured the victory of Song over Jin forces at the Battle of Caishi in 1161, while the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) used gunpowder bombs during their failed invasion of Japan in 1274 and 1281.[30] During the 13th and 14th centuries, gunpowder formulas became more potent (with nitrate levels of up to 91%) and gunpowder weaponry more advanced and deadly, as evidenced in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) military manuscript Huolongjing compiled by Jiao Yu (fl. 14th to early 15th century) and Liu Bowen (1311–1375). It was completed in 1412, a long while after Liu's death, with a preface added by the Jiao in its Nanyang publication.[32]

Compass

Although an ancient hematite artifact from the Olmec era in Mexico dating to roughly 1000 BC indicates the possible use of the lodestone compass long before it was described in China, the Olmecs did not have iron which the Chinese would discover could be magnetised by contact with lodestone.[34] Descriptions of lodestone attracting iron were made in the Guanzi, Master Lu's Spring and Autumn Annals and Huainanzi.[35][36][37] The Chinese by the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) began using north-south oriented lodestone ladle-and-bowl shaped compasses for divination and geomancy and not yet for navigation.[38][39][40] The Lunheng, written by Han dynasty writer, scientist, and philosopher Wang Chong (27 – c. 100 AD) stated in chapter 52: "This instrument resembles a spoon and when it is placed on a plate on the ground, the handle points to the south".[41][42] There are, however, another two references under chapter 47 of the same text to the attractive power of a magnet according to Needham (1986),[43] but Li Shu-hua (1954) considers it to be lodestone, and states that there is no explicit mention of a magnet in Lunheng.[33] The Chinese polymath Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song Dynasty (960–1279) was the first to accurately describe both magnetic declination (in discerning true north) and the magnetic needle compass in his Dream Pool Essays of 1088, while the Song dynasty writer Zhu Yu (fl. 12th century) was the first to mention use of the compass specifically for navigation at sea in his book published in 1119.[22][39][44][45][46][47][48] Even before this, however, the Wujing Zongyao military manuscript compiled by 1044 described a thermoremanence compass of heated iron or steel shaped as a fish and placed in a bowl of water which produced a weak magnetic force via remanence and induction; the Wujing Zongyao recorded that it was used as a pathfinder along with the mechanical south-pointing chariot.[49][50]

Pre-Shang

Inventions which originated in what is now China during the Neolithic age and prehistoric Bronze Age are listed in alphabetical order below.

- Alcoholic beverage and the process of fermentation: The earliest archaeological evidence of fermentation and the consumption of alcoholic beverages was discovered in neolithic China dating from 7000–6600 BC. Examination and analysis of ancient pottery jars from the neolithic village of Jiahu in Henan province in northern China revealed fermented residue left behind by the alcoholic beverages they once contained. According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, chemical analysis of the residue revealed that the fermented drink was made from fruit, rice and honey.[51][52] Elsewhere in the world, fermented beverages have been found dating from 6000 BC in Georgia,[53] 3150 BC in ancient Egypt,[54] 3000 BC in Babylon,[55] 2000 BC in pre-Hispanic Mexico,[55] and 1500 BC in Sudan.[56]

- Bell: Clapper-bells made of pottery have been found in several archaeological sites.[57] The earliest metal bells, with one found in the Taosi site, and four in the Erlitou site, dated to about 2000 BC, may have been derived from the earlier pottery prototype.[58] Early bells not only have an important role in generating metal sound, but arguably played a prominent cultural role. With the emergence of other kinds of bells during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1050 BC), they were relegated to subservient functions; at Shang and Zhou sites, they are also found as part of the horse-and-chariot gear and as collar-bells of dogs.[59]

- Coffin, wooden: The earliest evidence of wooden coffin remains, dated at 5000 BC, was found in the Tomb 4 at Beishouling, Shaanxi. Clear evidence of a wooden coffin in the form of a rectangular shape was found in Tomb 152 in an early Banpo site. The Banpo coffin belongs to a four-year-old girl, measuring 1.4 m (4.5 ft) by 0.55 m (1.8 ft) and 3–9 cm thick. As many as 10 wooden coffins have been found from the Dawenkou culture (4100–2600 BC) site at Chengzi, Shandong.[60][61] The thickness of the coffin, as determined by the number of timber frames in its composition, also emphasized the level of nobility, as mentioned in the Classic of Rites,[62] Xunzi[63] and Zhuangzi.[64] Examples of this have been found in several Neolithic sites; the double coffin, the earliest of which was found in the Liangzhu culture (3400–2250 BC) site at Puanqiao, Zhejiang, consists of an outer and an inner coffin, while the triple coffin, with its earliest finds from the Longshan culture (3000–2000 BC) sites at Xizhufeng and Yinjiacheng in Shandong, consists of two outer and one inner coffins.[65]

- Cookware and pottery vessel: The earliest pottery, used as vessels, was discovered in 2012, found in Xianrendong Cave located in the Jiangxi province of China.[66] The pottery dates to 20,000 to 19,000 BP.[67][68] The vessels may have been used as cookware, manufactured by hunter-gatherers.[68] The Israeli archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef reported that "When you look at the pots, you can see that they were in a fire."[69]

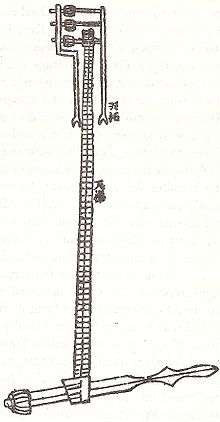

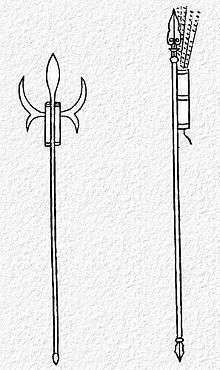

- Dagger-axe: The dagger-axe or ge was developed from agricultural stone implement during the Neolithic, dagger-axe made of stone are found in the Longshan culture (3000–2000 BC) site at Miaodian, Henan. It also appeared as ceremonial and symbolic jade weapon at around the same time, two being dated from about 2500 BC, are found at the Lingjiatan site in Anhui.[70] The first bronze ge appeared at the early Bronze Age Erlitou site,[70] where two were being found among the over 200 bronze artifacts (as of 2002) at the site,[71] three jade ge were also discovered from the same site.[72] Total of 72 bronze ge in Tomb 1004 at Houjiazhuang, Anyang,[73] 39 jade ge in tomb of Fu Hao and over 50 jade ge at Jinsha site were found alone.[70] It was the basic weapon of Shang (c. 1600 – 1050 BC) and Zhou (c.1050–256 BC) infantry, although it was sometimes used by the "striker" of charioteer crews. It consisted of a long wooden shaft with a bronze knife blade attached at a right angle to the end. The weapon could be swung down or inward in order to hook or slash, respectively, at an enemy.[74] By the early Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), military use of the bronze ge had become limited (mostly ceremonial); they were slowly phased out during the Han Dynasty by iron spears and iron ji halberds.[75]

- Deepwater drilling: Some of the earliest evidence of water wells are located in China. The Chinese discovered and made extensive use of deep drilled groundwater for drinking. The Chinese text The Book of Changes, originally a divination text of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 -771 BC), contains an entry describing how the ancient Chinese maintained their wells and protected their sources of water.[76] Archaeological evidence and old Chinese documents reveal that the prehistoric and ancient Chinese had the aptitude and skills for digging deep water wells for drinking water as early as 6000 to 7000 years ago. A well excavated at the Hemudu excavation site was believed to have been built during the Neolithic era.[77][78] The well was cased by four rows of logs with a square frame attached to them at the top of the well. 60 additional tile wells southwest of Beijing are also believed to have been built around 600 BC for drinking and irrigation.[77][79]

- Bricks, fired: The oldest fired bricks were found at the Neolithic Chinese site of Chengtoushan, dating back to 4400 BC.[80] They were made of red clay, baked on all sides, and used as flooring for houses. By 3300 BC, fired bricks were being used at Chengtoushan to pave roads and form building foundations, roughly at the same time as the Indus Valley Civilisation. While sun-dried bricks were used much earlier in Mesopotamia, fired bricks are significantly stronger as a building material. Bricks continued to be used during 2nd millennium BC at a site near Xi'an.[81] Fired bricks were found in Western Zhou (1046–771 BC) ruins, where they were produced on a large scale. The carpenter's manual Yingzao Fashi, published in 1103 during the medieval Chinese Song dynasty described the brick making process and glazing techniques then in use.[82][83][84]

- Gnomon: A painted stick dating from 2300 BCE excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the oldest gnomon known in China.[85] The gnomon was widely used in ancient China from the second century BC onward in order determine the changes in seasons, orientation, and geographical latitude. The ancient Chinese used shadow measurements for creating calendars that are mentioned in several ancient texts. According to the collection of Zhou Chinese poetic anthologies Classic of Poetry, one of the distant ancestors of King Wen of the Zhou dynasty used to measure gnomon shadow lengths to determine the orientation around the 14th-century BC.[86][87]

- Jadeworking: Chinese jade has played a role in China's science and technological history.[88] During Neolithic times, the key known sources of nephrite jade in China for utilitarian and ceremonial jade items were the now depleted deposits in the Ningshao area in the Yangtze River Delta (Liangzhu culture 3400–2250 BC) and in an area of the Liaoning province and Inner Mongolia (Hongshan culture 4700–2200 BC).[89] Dushan Jade was being mined as early as 6000 BC and the jade stone is the primary hardstone of Chinese sculpture. Jade was prized for its hardness, durability, musical qualities, and beauty.[90] In particular, its subtle, translucent colors and protective qualities[90] caused it to become associated with Chinese conceptions of the soul and immortality.[91] The most prominent early use was the crafting of the Six Ritual Jades found since the 3rd-millennium BC Liangzhu culture.[92]

- Lacquer: Lacquer was used in China since the Neolithic period and came from a substance extracted from the lac tree found in China.[93] A red wooden bowl, which is believed to be the earliest known lacquer container,[94] was unearthed at a Hemudu (c. 5000 BC – c. 4500 BC) site.[95] The British sinologist and historian Michael Loewe says coffins at many early Bronze Age sites seem to have been lacquered, and articles of lacquered wood may also have been common, but the earliest well-preserved examples of lacquer come from Eastern Zhou Dynasty (771 – 256 BC) sites.[96] However, Wang Zhongshu disagrees, stating that the oldest well-preserved lacquerware items come from a Xiajiadian (c.2000 – c.1600 BC) site in Liaoning excavated in 1977, the items being red lacquered vessels in the shape of Shang Dynasty bronze gu vessels.[95] Wang states that many lacquerware items from the Shang Dynasty (c.1600 – c.1050 BC), such as fragments of boxes and basins, were found, and had black designs such as the Chinese dragon and taotie over a red background.[95] Queen Fu Hao (died c. 1200 BC) was buried in a lacquered wooden coffin.[97] There were three imperial workshops during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) established solely for the purpose of crafting lacquerwares; fortunately for the historian, Han lacquerware items were inscribed with the location of the workshop where they were produced and the date they were made, such as a lacquerware beaker found in the Han colony in northwestern Korea with the inscription stating it was made in a workshop near Chengdu, Sichuan and dated precisely to 55 AD.[98]

- Millet cultivation: The discovery in northern China of domesticated varieties of broomcorn and foxtail millet from 8500 BC, or earlier, suggests that millet cultivation might have predated that of rice in parts of Asia.[99] Clear evidence of millet began to cultivate by 6500 BC at sites of Cishan, Peiligang and Jiahu.[100] Archaeological remains from Cishan sum up to over 300 storage pits, 80 with millet remains, with a total millet storage capacity estimated for the site of about 100,000 kg of grain.[101] By 4000 BC, most Yangshao areas were using an intensive form of foxtail millet cultivation, complete with storage pits and finely prepared tools for digging and harvesting the crop. The success of the early Chinese millet farmers is still reflected today in the DNA of many modern East Asian populations, such studies have shown that the ancestors of those farmers probably arrived in the area between 30,000 and 20,000 BP, and their bacterial haplotypes are still found in today populations throughout East Asia.[102]

- Rowing oar: Rowing oars have been used since the early Neothilic period; a canoe-shaped pottery and six wooden oars dating from the 6000 BC have been discovered in a Hemudu culture site at Yuyao, Zhejiang.[103][104] In 1999, an oar measuring 63.4 cm (2 ft) in length, dating from 4000 BC, has also been unearthed at Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan.[105]

- Plastromancy: The earliest use of turtle shells comes from the archaeological site in Jiahu site. The shells, containing small pebbles of various size, colour and quantity, were drilled with small holes, suggesting that each pair of them was tied together originally. Similar finds have also been found in the Dawenkou burial sites of about 4000–3000 BC, as well as in Henan, Sichuan, Jiangsu and Shaanxi.[106] The turtle-shell shakers for the most part are made of the shell of land turtles,[107] identified as Cuora flavomarginata.[108] Archaeologists believe that these shells were used either as rattles in ceremonial dances, shamantic healing tools or ritual paraphernalia for divinational purposes.[109]

- Ploughshare, triangular-shaped: Triangular-shaped stone ploughshares are found at the sites of Majiabang culture dated to 3500 BC around Lake Tai. Ploughshares have also been discovered at the nearby Liangzhu and Maqiao sites roughly dated to the same period. David R. Harris says this indicates that more intensive cultivation in fixed, probably bunded, fields had developed by this time. According to Mu Yongkang and Song Zhaolin's classification and methods of use, the triangular plough assumed many kinds and were the departure from the Hemudu and Luojiajiao spade, with the Songze small plough in mid-process. The post-Liangzhu ploughs used draft animals.[110][111]

- Pottery steamer: Archaeological excavations show that using steam to cook began with the pottery cooking vessels known as yan steamers; a yan composed of two vessel, a zeng with perforated floor surmounted on a pot or caldron with a tripod base and a top cover. The earliest yan steamer dating from about 5000 BC was unearthed in the Banpo site.[112] In the lower Yangzi River, zeng pots first appeared in the Hemudu culture (5000–4500 BC) and Liangzhu culture (3200–2000 BC) and used to steam rice; there are also yan steamers unearthed in several Liangzhu sites, including 3 found at the Chuodun and Luodun sites in southern Jiangsu.[113] In the Longshan culture (3000–2000 BC) site at Tianwang in western Shandong, 3 large yan steamers were discovered.[114]

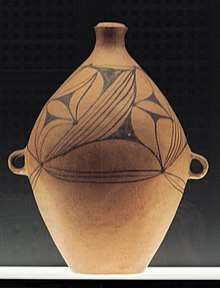

- Pottery urn: The first evidence of pottery urn dating from about 7000 BC comes from the early Jiahu site, where a total of 32 burial urns are found,[115] another early finds are in Laoguantai, Shaanxi.[65] There are about 700 burial urns unearthed over the Yangshao (5000–3000 BC) areas and consisting more than 50 varieties of form and shape. The burial urns were used mainly for children, but also sporadically for adults, as shown in the finds at Yichuan, Lushan and Zhengzhou in Henan.[60] A secondary burials containing bones from child or adult are found in the urns in Hongshanmiao, Henan.[116] Small hole was drilled in most of the child and adult burial urns, and is believed to enable the spirit to access.[117] It is recorded in the Classic of Rites that the earthenware coffins were used in the time of legendary period,[118] the tradition of burying in pottery urns lasted until the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD) when it gradually disappeared.[65]

.jpg)

- Quern stones: Quern stones were used in China at least 10,000 years ago to grind wheat into flour. The production of flour by rubbing wheat by hand took several hours.[119] Due to their form, dimensions, and the nature of the treatment of the surfaces, they reproduce precisely the most ancient implements used for grinding cereal grain into flour. Saddle querns were known in China during the Neolithic Age but rotary stone mills did not appear until the Warring States Period.[120] A prehistoric quern dating back to 23,000 BCE was found at the Longwangchan archaeological site, in Hukou, Shaanxi in 2007. The site is located in the heartland of the northern Chinese loess plateau near the Yellow River.[121]

- Rammed earth: The archaeological evidence of the use of rammed earth has been discovered in Neolithic archaeological sites of the Yangshao and Longshan cultures along the Chinese Yellow River, dating back to 5000 BC. By 2000 BC, rammed-earth architectural techniques were commonly used for walls and foundations in China.[122]

- Rice cultivation: In 2002, a Chinese and Japanese group reported the discovery in eastern China of fossilised phytoliths of domesticated rice apparently dating back to 11,900 BC or earlier. However, phytolith data are controversial in some quarters due to potential contamination problems.[123] It is likely that demonstrated rice was cultivated in the middle Yangtze Valley by 7000 BC, as shown in finds from the Pengtoushan culture at Bashidang, Changde, Hunan. By 5000 BC, rice had been domesticated at Hemudu culture near the Yangtze Delta and was being cooked in pots.[124] Although millet remained the main crop in northern China throughout history, several sporadic attempts were made by the state to introduce rice around the Bohai Gulf as early as the 1st century.[125]

- Saltern: One of the earliest salterns for the harvesting of salt is argued to have taken place on Lake Yuncheng, Shanxi by 6000 BC.[126] Strong archaeological evidence of salt making dating to 2000 BC is found in the ruins of Zhongba at Chongqing.[127][128]

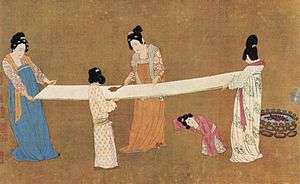

- Sericulture: Sericulture is the production of silk from silkworms. The oldest silk found in China comes from the Chinese Neolithic period and is dated to about 3630 BC, found in Henan province.[129] Silk items excavated from the Liangzhu culture site at Qianshanyang, Wuxing District, Zhejiang date to roughly 2570 BC, and include silk threads, a braided silk belt and a piece of woven silk.[129] A bronze fragment found at the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1050 BC) site at Anyang (or Yinxu) contains the first known written reference to silk.[130]

- Soybean cultivation: The cultivation of soybeans began in the eastern half of northern China by 2000 BC, but is almost certainly much older.[131] Liu et al. (1997) stated that soybean originated in China and was domesticated about 3500 BC.[132] By the 5th century, soybeans were being cultivated in much of East Asia, but the crop did not move beyond this region until well into the 20th century.[133] Written records of the cultivation and use of the soybean in China date back at least as far as the Western Zhou Dynasty.[134]

- Wet field cultivation and paddy field: Wet field cultivation, or the paddy field, was developed in China. The earliest paddy field dates to 6280 BP, based on carbon dating of the grains of rice and soil organic matter found at the Chaodun site in Kushan County.[135] Paddy fields have also been excavated by archaeologists at Caoxieshan, a site of the Neolithic Majiabang culture.[136]

Shang and later

Inventions which made their first appearance in China after the Neolithic age, specifically during and after the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1050 BC), are listed in alphabetical order below.

A

- Acupuncture: Acupuncture, the traditional Chinese medicinal practice of inserting needles into specific points of the body for therapeutic purposes and relieving pain, was first mentioned in the Huangdi Neijing compiled from the 3rd to 2nd centuries BC (Warring States period to Han Dynasty).[137] The oldest known acupuncture sticks made of gold, found in the tomb of Liu Sheng (d. 113 BC), date to the Western Han (203 BC – 9 AD); the oldest known stone-carved depiction of acupuncture was made during the Eastern Han (25–220 AD); the oldest known bronze statue of an acupuncture mannequin dates to 1027 during the Song Dynasty (960–1279).[138]

- Animal zodiac: The earliest and most complete version of the animal zodiac mentions twelve animals which differ slightly from the modern version (for instance, the Dragon is absent, represented by a worm).[139] Each animal matches the Earthly Branches and were written on bamboo slips from Shuihudi, dated to the late 4th century BC,[140] as well as from Fangmatan, dating to the late 3rd century BC.[140] Before these archaeological finds, the Lunheng written by Wang Chong (27 – c. 100 AD) during the 1st century provided the earliest transmitted example of a complete duodenary animal cycle.[141]

- Armillary sphere, hydraulic-powered: Hipparchus (c. 190 – c. 120 BC)[142] credited the Ancient Greek mathematician, geographer, astronomer, and poet Eratosthenes (276–194 BC) as the first to invent the armillary sphere representing the celestial sphere. However, the Chinese astronomer Geng Shouchang of the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) invented it separately in China in 52 BC, while the Han dynasty polymath Zhang Heng (78–139 AD) was the first to apply motive power to the rotating armillary sphere by a set of complex gears rotated by a waterwheel which in turn was powered by the constant pressure head of an inflow clepsydra clock, the latter of which he improved with an extra compensating tank between the reservoir and the inflow vessel.[143][144][145][146][147]

- Artillery: Early Chinese artillery had vase-like shapes. This includes the "long range awe inspiring" cannon dated from 1350 and found in the 14th century Ming Dynasty treatise Huolongjing.[148] With the development of better metallurgy techniques, later cannons abandoned the vase shape of early Chinese artillery. This change can be seen in the bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon," an early example of field artillery.[149]

B

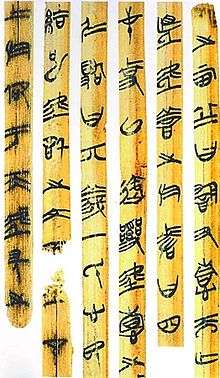

- Bamboo and wooden slips: Bamboo and wooden slips (Chinese: 简牍; pinyin: jiǎndú) were the main medium for documents in China before the widespread introduction of paper by the 2nd century AD. (Silk was occasionally used, but was prohibitively expensive.) The long, narrow strips of wood or bamboo typically carry a single column of brush-written text each, with space for several tens of visually complex ancient Chinese characters. For longer texts, many slips may be bound together in sequence with thread. Each strip of wood or bamboo is said to be as long as a chopstick and as wide as two. The earliest surviving examples of wood or bamboo slips date from the 5th century BC during the Warring States period. However, references in earlier texts surviving on other media make it clear that some precursor of these Warring States period bamboo slips was in use as early as the late Shang period (from about 1250 BC). Bamboo or wooden strips were the standard writing material during the Han dynasty and excavated examples have been found in abundance.[151] Bamboo tablets were used to write on before paper was invented by Cai Lun during the Han dynasty. Slats of bamboo stalks were sewn together used to make a kind of folding book.[152] Subsequently, the invention of paper during the Han dynasty began to displace bamboo and wooden strips from mainstream uses, and by the 4th century AD bamboo had been largely phased out as a medium for writing in China.

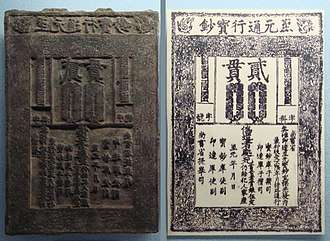

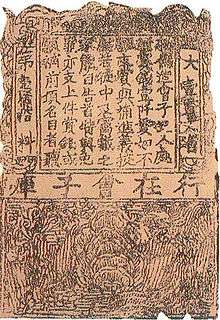

- Banknote: Paper currency was first developed in China. Its roots were in merchant receipts of deposit during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), as merchants and wholesalers desired to avoid the heavy bulk of copper coinage in large commercial transactions.[153][154][155] During the Song Dynasty (960–1279), the central government adopted this system for their monopolized salt industry, but a gradual reduction in copper production—due to closed mines and an enormous outflow of Song-minted copper currency into the Japanese, Southeast Asian, Western Xia and Liao Dynasty economies—encouraged the Song government in the early 12th century to issue government-printed paper currency alongside copper to ease the demand on their state mints and debase the value of copper.[156] In the early 11th century, the Song Dynasty government authorised sixteen private banks to issue notes of exchange in Sichuan, but in 1023 the government commandeered this enterprise and set up an agency to supervise the manufacture of banknotes there. The earliest paper currency was limited to certain regions and could not be used outside specified bounds, but once paper was securely backed by gold and silver stores, the Song Dynasty government initiated a nationwide paper currency, between 1265 and 1274.[155] The concurrent Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) also printed paper banknotes by at least 1214.[157]

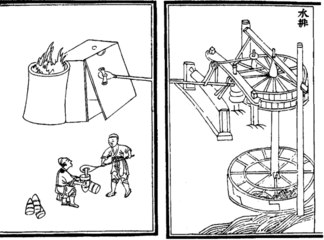

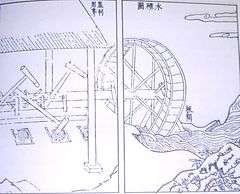

- Bellows, hydraulic-powered: The manufacturing of different alloys in China often required a continuous stream of air that was able to be blown over through molten metals. The use of double-action piston bellows was described by Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu around 500 BC to produce a continuous stream of air.[158] Although it is unknown if metallurgic bellows (i.e. air-blowing device) in the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) were of the leather bag type or the wooden fan type found in the later Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), the Eastern Han dynasty mechanical engineer and politician Du Shi (d. 38 AD) applied the use of rotating waterwheels to power the bellows of his blast furnace smelting iron, a method which continued in use in China thereafter, as evidenced by subsequent records; it is a significant invention in that iron production yields were increased and it employed all the necessary components for converting rotary motion into reciprocating motion.[147][159][160][161][162]

- Belt drive: The mechanical belt drive, using a pulley machine, was first mentioned in the text the Dictionary of Local Expressions by the Han Dynasty philosopher, poet, and politician Yang Xiong (53–18 BC) in 15 BC, used for a quilling machine that wound silk fibers on to bobbins for weavers' shuttles.[150] The belt drive is an essential component to the invention of the spinning wheel.[163][164] The belt drive was not only used in textile technologies, it was also applied to hydraulic powered bellows dated from the 1st century AD.[163]

- Belt hook: The belt hook was a fastener used in China. Belt hooks date to the 7th century BC in China,[165] and were made with bronze, iron, gold, and jade.[165] Texts claim that the belt hook arrived in China from Central Asia during the Warring States period, but archaeological evidence of belt hooks in China predate the Warring States Period.[166]

- Bintie: Bintie (simplified Chinese: 镔铁; traditional Chinese: 鑌鐵) was a type of refined iron, which was known for its hardness. It was often used in the making of Chinese weapons. The metal alloy was an important article of income in medieval Yuan China as technological advances from the preceding Song dynasty improved Yuan smelting technology. Bintie was referred as "fine steel", due to its high carbon content.[167][168]

- Biological pest control: The first report of the use of an insect species to control an insect pest comes from "Nan Fang Cao Mu Zhuang" (南方草木狀 Plants of the Southern Regions) (ca. 304 AD), attributed to Western Jin dynasty botanist Ji Han (嵇含, 263–307), in which it is mentioned that "Jiaozhi people sell ants and their nests attached to twigs looking like thin cotton envelopes, the reddish-yellow ant being larger than normal. Without such ants, southern citrus fruits will be severely insect-damaged".[169] The ants used are known as huang gan (huang = yellow, gan = citrus) ants (Oecophylla smaragdina). The practice was later reported by Ling Biao Lu Yi (late Tang Dynasty or Early Five Dynasties), in Ji Le Pian by Zhuang Jisu (Southern Song Dynasty), in the Book of Tree Planting by Yu Zhen Mu (Ming Dynasty), in the book Guangdong Xing Yu (17th century), Lingnan by Wu Zhen Fang (Qing Dynasty), in Nanyue Miscellanies by Li Diao Yuan, and others.[169]

- Blast furnace: Although cast iron tools and weapons have been found in China dating to the 5th century BC, the earliest discovered Chinese blast furnaces, which produced pig iron that could be remelted and refined as cast iron in the cupola furnace, date to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, while the vast majority of early blast furnace sites discovered date to the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) period immediately following 117 BC with the establishment of state monopolies over the salt and iron industries during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141 – 87 BC); most ironwork sites discovered dating before 117 BC acted merely as foundries which made castings for iron that had been smelted in blast furnaces elsewhere in remote areas far from population centres.[170][171]

- Bombard weaponry: The oldest representation of a bombard can be found in the Chinese town of Ta-tsu. In 1985, the Canadian historian Robin Yates visited the Buddhist cave temples when he saw a sculpture on the wall depicting a demon holding a hand-held bombard. The muzzle seems to have a blast and flames coming from it which some believe is proof of some type of super gun. Yates examined the cave and believed the drawings dated back to the late 12th century.[172]

- Bomb, cast iron: The first accounts of bombs made of cast iron shells packed with explosive gunpowder—as opposed to earlier types of casings—were written in the 13th century in China.[173] The term was coined for this bomb (i.e. "thunder-crash bomb") during a Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) naval battle of 1231 against the Mongols.[174] The History of Jin (compiled by 1345) states that in 1232, as the Mongol general Subutai (1176–1248) descended on the Jin stronghold of Kaifeng, the defenders had a "thunder-crash bomb" which "consisted of gunpowder put into an iron container ... then when the fuse was lit (and the projectile shot off) there was a great explosion the noise whereof was like thunder, audible for more than a hundred li, and the vegetation was scorched and blasted by the heat over an area of more than half a mou. When hit, even iron armour was quite pierced through."[174] The Song Dynasty (960–1279) official Li Zengbo wrote in 1257 that arsenals should have several hundred thousand iron bomb shells available and that when he was in Jingzhou, about one to two thousand were produced each month for dispatch of ten to twenty thousand at a time to Xiangyang and Yingzhou.[175] The significance of this, as British sinologist, scientist, and historian Joseph Needham states, is that a "high-nitrate gunpowder mixture had been reached at last, since nothing less would have burst the iron casing."[176]

- Borehole drilling: By at least the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), the Chinese used deep borehole drilling for mining and other projects; The British sinologist and historian Michael Loewe states that borehole sites could reach as deep as 600 m (2000 ft).[177] K.S. Tom describes the drilling process: "The Chinese method of deep drilling was accomplished by a team of men jumping on and off a beam to impact the drilling bit while the boring tool was rotated by buffalo and oxen."[178] This was the same method used for extracting petroleum in California during the 1860s (i.e. "Kicking Her Down").[178][179] A Western Han Dynasty bronze foundry discovered in Xinglong, Hebei had nearby mining shafts which reached depths of 100 m (328 ft) with spacious mining areas; the shafts and rooms were complete with a timber frame, ladders and iron tools.[180][181] By the first century BC, Chinese craftsmen cast iron drill bits and drillers were able to drill boreholes up to 4800 feet (1500 m) deep.[182][183][184] By the eleventh century AD, the Chinese were able to drill boreholes up to 3000 feet in depth. Drilling for boreholes was time consuming and long. As the depth of the holes varied, the drilling of a single well could up to nearly one full decade.[178] It wasn't up until the 19th century that Europe and the West would catch up and rival ancient Chinese borehole drilling technology.[184][179]

- Brandy: The traditional making of brandy has its roots in medieval China during the Tang dynasty. The Chinese started to distill brandy by heating wine in the 6th century AD.[185][186] By the 7th century AD, distilled wine was known and widespread through China. The production of frozen brandy was widespread among Central Asian tribes in the frigid climate in the third century AD.[187] This process was recorded in the Chinese compendium Records of the Investigations of Things by Zhang Hua of the Jin dynasty in 290 AD.[188]

- Breeching strap: The breeching strap traces its roots back to the Chinese invented breast-strap or "breastcollar" harness developed during the Warring States (481–221 BC) era.[189] The Chinese breast harness became known throughout Central Asia by the 7th century,[190] introduced to Europe by the 8th century.[190] The breeching strap would allow the horse to hold or brake the load as horse harnesses were previously attached to vehicles by straps around their necks as previously designed harnesses would constrict the horses neck preventing the horse from pulling heavier loads.[191] The breeching strap acted as a brake when a cart tries to run forward when moving downwards on a slope and also make it possible to maneuver the cart in the reverse direction.[192][191]

- Brine mining: Around 500 BCE, the ancient Chinese dug hundreds of brine wells, some of which were over 100 meters (330 feet) in depth. Large brine deposits under the earth's surface were drilled by drilling boreholes.[178] Bamboo towers were erected, similar in style to modern-day oil derricks.[193] Bamboo was used for ropes, casing, and derricks since it was salt resistant.[194] Iron wedges were hung from a bamboo cable tool attached to a lever on a platform constructed atop the tower. The derricks required two to three men jumping on and off the lever that moved the iron wedge pounded into the ground to dig a hole deep enough into the ground to hit the brine.[194][193]

- Bristle toothbrush: According to the United States Library of Congress website, the Chinese have used the bristle toothbrush since 1498, during the reign of the Hongzhi Emperor (r. 1487–1505) of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644); it also adds that the toothbrush was not mass-produced until 1780, when they were sold by a William Addis of Clerkenwell, London, England.[195] In accordance with the Library of Congress website, scholar John Bowman also writes that the bristle toothbrush using pig bristles was invented in China during the 1490s.[26] While Bonnie L. Kendall agrees with this, she noted that a predecessor existed in ancient Egypt in the form of a twig that was frayed at the end.[196]

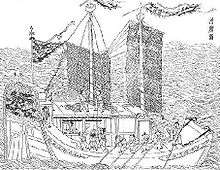

- Bulkhead partition: The 5th century book Garden of Strange Things by Liu Jingshu mentioned that a ship could allow water to enter the bottom without sinking, while the Song Dynasty author Zhu Yu (fl. 12th century) wrote in his book of 1119 that the hulls of Chinese ships had a bulkhead build; these pieces of literary evidence for bulkhead partitions are confirmed by archaeological evidence of a 24 m (78 ft) long Song Dynasty ship dredged from the waters off the southern coast of China in 1973, the hull of the ship divided into twelve walled compartmental sections built watertight, dated to about 1277.[197][198] Western writers from Marco Polo (1254–1324), to Niccolò Da Conti (1395–1469), to Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) commented on bulkhead partitions, which they viewed as an original aspect of Chinese shipbuilding, as Western shipbuilding did not incorporate this hull arrangement until the early 19th century.[199][200]

C

- Candle clock: Candle clocks have been used in China since at least the 6th century AD. The earliest reference of a candle clock is in a poem by You Jiangu around 520 AD.[203]

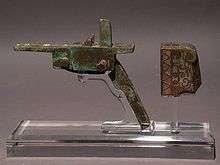

- Cannon: The earliest known depiction of a cannon is a sculpture from the Dazu Rock Carvings in Sichuan dated to 1128,[204] however the earliest archaeological samples and textual accounts do not appear until the 13th century. The primary extant specimens of cannon from the 13th century are the Wuwei Bronze Cannon dated to 1227, the Heilongjiang hand cannon dated to 1288, and the Xanadu Gun dated to 1298. However, only the Xanadu gun contains an inscription bearing a date of production, so it is considered the earliest confirmed extant cannon. The Xanadu Gun is 34.7 cm in length and weighs 6.2 kg. The other cannon are dated using contextual evidence.[205]

- Cast iron: Confirmed by archaeological evidence, cast iron, made from melting pig iron, was developed in China by the early 5th century BC during the Zhou Dynasty (1122–256 BC), the oldest specimens found in a tomb of Luhe County in Jiangsu province; despite this, most of the early blast furnaces and cupola furnaces discovered in China date after the state iron monopoly under Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC) was established in 117 BC, during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD); Donald Wagner states that a possible reason why no ancient Chinese bloomery process has been discovered thus far is because the iron monopoly, which lasted until the 1st century AD when it was abolished for private entrepreneurship and local administrative use, wiped out any need for continuing the less-efficient bloomery process that continued in use in other parts of the world.[170][206][207][208][209] Wagner states that most iron tools in ancient China were made of cast iron in consideration of the low economic burden of producing cast iron, whereas most iron military weapons were made of more costly wrought iron and steel, signifying that "high performance was essential" and preferred for the latter.[210] As cast iron is comparatively brittle, it is not suitable for purposes where a sharp edge or flexibility is required. It is strong under compression, but not under tension. Cast iron found many uses in ancient Chinese society as it was poured into moulds to make ploughshares, cooking utensils as well as weapons and pagodas.[211] Cast iron would not become available in Europe until the 15th century, where Henry VIII initiated the casting of cannons and cannonballs in England.[212]

- Celadon: Named after a pale-tinted spring green colour, Chinese archaeologist Wang Zhongshu (1982) asserts that shards having this type of ceramic glaze have been recovered from Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD) tomb excavations in Zhejiang; he also asserts that this type of ceramic became well known during the Three Kingdoms (220–265).[213] Richard Dewar (2002) disagrees with Wang's classification, stating that true celadon—which requires a minimum 1260 °C (2300 °F) furnace temperature, a preferred range of 1285° to 1305 °C (2345° to 2381 °F), and reduced firing—was not created until the beginning of the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127).[214] The unique grey or green celadon glaze is a result of iron oxide's transformation from ferric to ferrous iron (Fe2O3 → FeO) during the firing process.[214] Longquan celadon wares, which the archeologist Nigel Wood at the University of Oxford writes were first made during the Northern Song, had bluish, blue-green, and olive green glazes and high silica and alkali contents which resembled later porcelain wares made at Jingdezhen and Dehua rather than stonewares.[215]

- Chain drive, endless power-transmitting: The Greek Philon of Byzantium (3rd or 2nd century BC)[216] described a chain drive and windlass used in the operation of a polybolos (a repeating ballista),[217][218] "but the chain drive did not continuously transmit power from shaft to shaft and hence they were not in the direct line of ancestry of the chain-drive proper".[219] A continuously driven chain drive first appeared in 11th century China. Perhaps inspired by chain pumps which had been known in China since at least the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) when they were mentioned by the Han dynasty philosopher Wang Chong (27 – c. 100 AD),[220] the endless power-transmitting chain drive was first used in the gearing of the clock tower built at Kaifeng in 1090 by the Song Chinese politician, mathematician and astronomer Su Song (1020–1101).[221][222][223]

- Chain stitch: The earliest archaeological evidence of chain stitch embroidery dates from 1100 BC in China. Excavated from royal tombs, the embroidery was made using threads of silk.[224] Chain stitch embroidery has also been found dating to the Warring States period. Chain stitch designs spread to Iran through the Silk Road.[225]

- Chopsticks: The Han dynasty historian and writer Sima Qian (145–86 BC) wrote in the Records of the Grand Historian that King Zhou of Shang was the first to make chopsticks out of ivory in the 11th century BC; the most ancient archaeological find of a pair of chopsticks, made of bronze, comes from Shang Tomb 1005 at Houjiazhuang, Anyang, dated roughly 1200 BC. By 600 BC, the use of chopsticks had spread to Yunnan (Dapona in Dali),[226][227] and Töv Province by the 1st century.[228] The earliest known textual reference to the use of chopsticks comes from the Han Feizi, a philosophical text written by writer and philosopher Han Fei (c. 280–233 BC) in the 3rd century BC.[229]

- Chromium, use of: The use of chromium was invented in China no later than 210 BC when the Terracotta Army was interred at a site not far from modern Xi'an; modern archaeologists discovered that bronze-tipped crossbow bolts at the site showed no sign of corrosion after more than 2,000 years, because they had been coated in chromium. Chromium was not used anywhere else until the experiments of French pharmacist and chemist Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1763–1829) in the late 1790s.[230]

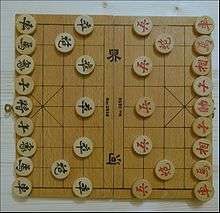

- Chuiwan: Chuiwan, a game similar to the Scottish-derived sport of golf, was first mentioned in China by Song dynasty writer Wei Tai (fl. 1050–1100) in his Dongxuan Records (東軒錄);[231] it was popular amongst men and women in the Song Dynasty (960–1279) and Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), while it was popular among urban men in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) in much the same way that tennis was for early urban Europeans during the Renaissance (according to Andrew Leibs).[232] In 1282, the writer Ning Zhi published the Book of Chuiwan, which described the rules, equipment, and playing field of chuiwan, as well as included commentary of those who mastered its tactics.[232] The game was played on flat and sloping grassland terrain and—much like the tee of modern golf—had a "base" area where the first of three strokes were played.[233]

- Civil service examinations: During the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), the xiaolian system of recruiting government officials through formal recommendations was the chief method of filling bureaucratic posts, although there was an Imperial Academy to train potential candidates for office and some offices required its candidates to pass formal written tests before appointment.[234][235][236][237] However, it was not until the Sui Dynasty (581–618) that civil service examinations became open to all adult males not belonging to the merchant class (although civil service examinations was a path to social advancement in Imperial Chinese society to candidates regardless of wealth, social status, or family background) and were used as a universal prerequisite for appointments to office, at least in theory.[238][239] The civil service system was implemented on a much larger scale during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), when an elite core of dynastic-founding and professional families lost their majority in government to a broad strata of lesser gentry families from throughout the country.[240][241] The civil examination system was later adopted by China's other East Asian neighbors Japan and Korea.[242] The imperial examination system attracted much attention and greatly inspired political theorists in the Western World, and as a Chinese institution was one of the earliest to receive such foreign attention.[243] The Chinese examination system was introduced to the Western world in reports by European missionaries and diplomats, and encouraged the British East India Company to use a similar method to select prospective employees. Following the initial success in that company, the British government adopted a similar testing system for screening civil servants in 1855.[244] Other European nations, such as France and Germany, followed suit. Modeled after these previous adaptations, the United States established its own testing program for certain government jobs after 1883.

- Co-fusion steel process: Although British scientist, sinologist, and historian Joseph Needham speculates that it could have existed beforehand, the first clear written evidence of the fusion of wrought iron and cast iron to make steel comes from the 6th century AD in regards to the Daoist swordsmith Qiwu Huaiwen, who was put in charge of the arsenal of Northern Wei general Gao Huan from 543 to 550 AD.[245] The Tang Dynasty (618–907) Newly Reorganized Pharmacopoeia of 659 also described this process of mixing and heating wrought iron and cast iron together, stating that the steel product was used to make sickles and Chinese sabers. In regards to the latter text, Su Song (1020–1101) made a similar description and noted the steel's use for making swords.

- Coke as fuel: By the 11th century, during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), the demands for charcoal used in the blast and cupola furnaces of the iron industry led to large amounts of deforestation of prime timberland; to avoid excessive deforestation, the Song Dynasty Chinese began using coke made from bituminous coal as fuel for their metallurgic furnaces instead of charcoal derived from wood.[246][247][248]

- Color printing: By at least the Yuan Dynasty, China had invented color printing for paper. British art historian Michael Sullivan writes that "the earliest color printing known in China, and indeed in the whole world, is a two-color frontispiece to a Buddhist sutra scroll, dated 1346".[249]

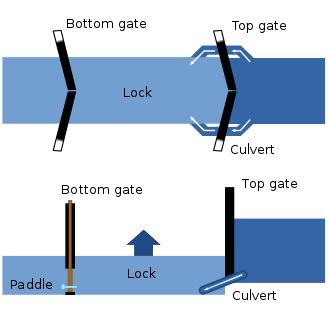

- Contour canal: After numerous conquests and consolidation of his empire, China's first emperor Qin Shi Huang (r. 221–210 BC) commissioned the engineer Shi Lu to build a new waterway canal which would pass through a mountain range and connect the Xiang and Lijiang rivers.[48] The result of this project was the Lingqu Canal, complete with thirty-six lock gates, and since it closely follows a contour line (i.e. following the contours of the natural saddle in the hills), it is the oldest known contour canal in the world.[48]

- Counting rods: Counting rods were used by ancient Chinese for more than two thousand years. In 1954, forty-odd counting rods of the Warring States period were found in Zuǒjiāgōngshān (左家公山) Chu Grave No.15 in Changsha, Hunan.[250][251] In 1973, archeologists unearthed a number of wood scripts from a Han dynasty tomb in Hubei. On one of the wooden scripts was written: “当利二月定算

- Crank and crankshaft: The earliest hand-operated cranks appeared in China during the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD), as Han era glazed-earthenware tomb models portray, and was used thereafter in China for silk-reeling and hemp-spinning, for the agricultural winnowing fan, in the water-powered flour-sifter, for hydraulic-powered metallurgic bellows, and in the well windlass.[254] In order to create a handle by means of a wheel to easily rotate their grain winnowers, the Chinese invented the crank handle and applied the centrifugal fan principle in the 2nd century BC.[255][256] The crank handle was used in well-windlasses, querns, mills, and many silk making machines.[255][256] The rotary winnowing fan greatly increased the efficiency of separating grain from husks and stalks. Harvesting grain by the use of rotary winnowing fan would not reach the Western World until the eighteenth century, where harvested grain was initially thrown up in the air by shovels or winnowing baskets.[257][258] However, the potential of the crank of converting circular motion into a reciprocal one never seems to have been fully realized in China, and the crank was typically absent from such machines until the turn of the 20th century.[259]

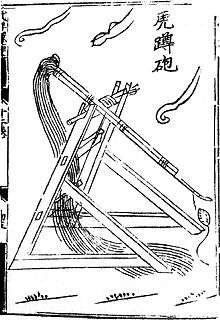

- Crossbow and repeating crossbow: According to British art historian Matthew Landruss and Gerald Hurley, Chinese crossbows may have been invented as far back as 2000 BC,[260][261] while the American historian Anne McCants at the Massachusetts institute of Technology speculates that they existed around 1200 BC.[262] In China bronze crossbow bolts dating as early as the mid 5th century BC were found at a State of Chu burial site in Yutaishan, Hubei.[263] The earliest handheld crossbow stocks with bronze trigger, dating from the 6th century BC, comes from Tomb 3 and 12 found at Qufu, Shandong, capital of the State of Lu.[202][264] Other early finds of crossbows were discovered in Tomb 138 at Saobatang, Hunan dated to the mid 4th century BC.[265][266] Repeating crossbows, first mentioned in the Records of the Three Kingdoms, were discovered in 1986 in Tomb 47 at Qinjiazui, Hubei dated to around the 4th century BC.[267] The earliest textual evidence of the handheld crossbow used in battle dates to the 4th century BC.[268] Handheld crossbows with complex bronze trigger mechanisms have also been found with the Terracotta Army in the tomb of Qin Shihuang (r. 221–210 BC) that are similar to specimens from the subsequent Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), while crossbowmen described in the Han Dynasty learned drill formations, some were even mounted as cavalry units, and Han dynasty writers attributed the success of numerous battles against the Xiongnu to massed crossbow fire.[269][270]

- Cuju (football): The game of football known as cuju was first mentioned in China by two historical texts; the Zhan Guo Ce (compiled from the 3rd to 1st centuries BC) and the Records of the Grand Historian (published in 91 BC) by Sima Qian (145–86 BC).[271] Both texts recorded that during the Warring States period (403–221 BC) the people of Linzi city, capital of the State of Qi, enjoyed playing cuju along with partaking in many other pastimes such as cockfighting.[271] Besides being a recreational sport, playing cuju was also considered a military training exercise and means for soldiers to keep fit.[271]

- Cupola furnace: American anthropologist Vincent C. Pigott of the University of Pennsylvania states that the cupola furnace existed in China at least by the Warring States period (403–221 BC),[272] while Donald B. Wagner writes that some iron ore melted in the blast furnace may have been cast directly into molds, but most, if not all, iron smelted in the blast furnace during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) was remelted in a cupola furnace; it was designed so that a cold blast injected at the bottom traveled through tuyere pipes across the top where the charge (i.e. of charcoal and scrap or pig iron) was dumped, the air becoming a hot blast before reaching the bottom of the furnace where the iron was melted and then drained into appropriate molds for casting.[273]

D

- Dao: Daos are single-edged Chinese swords, primarily used for slashing and chopping. The most common form is also known as the Chinese sabre, although those with wider blades are sometimes referred to as Chinese broadswords. In China, the dao is considered one of the four traditional weapons, along with the gun (stick or staff), qiang (spear), and the jian (sword). The earliest dao date from the Shang Dynasty in China's Bronze Age, and are known as zhibeidao (直背刀) – straight backed knives. As the name implies, these were straight-bladed or slightly curved weapons with a single edge. Originally bronze, these weapons were made of iron or steel by the time of the late Warring States period as metallurgical knowledge became sufficiently advanced to control the carbon content. Originally less common as a military weapon than the jian – the straight, double-edged blade of China – the dao became popular with cavalry during the Han dynasty due to its sturdiness, superiority as a chopping weapon, and relative ease of use – it was generally said that it takes a week to attain competence with a dao/saber, a month to attain competence with a qiang/spear, and a year to attain competence with a jian/straight sword. Soon after dao began to be issued to infantry, beginning the replacement of the jian as a standard-issue weapon.[274][275] Late Han dynasty dao had round grips and ring-shaped pommels, and ranged between 85 and 114 centimeters in length. These weapons were used alongside rectangular shields.[276]

- Dental amalgam: Dental amalgam were used in the first part of the Tang Dynasty in China (618-907 A.D.), and in Germany by Dr. Strockerus in about 1528.[277] Evidence of a dental amalgam first appears in the Tang Dynasty medical text Hsin Hsiu Pen Tsao written by Su Kung in 659, manufactured from tin and silver.[278] Historical records hint that the use of amalgams may date even earlier in the Tang Dynasty.[278] It was during the Ming Dynasty that the composition of an early dental amalgam was first published, and a text written by Liu Wen Taiin 1505 states that it consists of "100 shares of mercury, 45 shares of silver and 900 shares of tin."[278]

- Diabolo: Chinese archaeologists theorize that Chinese Diabolos (or Chinese yo-yo) originated from Chinese spinning top. In Hemudu Excavation, wooden tops were excavated. In order to extend the spinning time of the tops, whip were used to spin the top. This released a sound and gradually evolved into the term "Kongzhu" (Chinese: 空竹; pinyin: Kōng zhú; literally: "Air Bamboo" ). It was speculated that the Chinese poet Cao Zhi in the Three Kingdoms period had composed the poem "Rhapsody of Diabolos 《空竹赋》", making it the first record of Diabolo in Chinese history. The authenticity of the poem "Rhapsody of Diabolos 《空竹赋》" however required further research and evidence of proof. By the medieval Tang dynasty, Chinese Diabolo became widespread as a form of toy. The Taiwanese scholar Wu Shengda 吳盛達 however argued that records of Chinese Diabolo only appeared during late Ming dynasty Wanli period, with its details well recorded in the book Dijing Jingwulue, referring to Diabolos as "Kong Zhong" (simplified Chinese: 空钟; traditional Chinese: 空鐘; pinyin: Kōng zhong; literally: "Air Bell" ). Diabolos evolved from the Chinese yo-yo, which was originally standardized in the 12th century.[279][280] The first mention of a diabolo in the Western World was made by a missionary, Father Amiot, in Beijing in 1792 during Lord Macartney's ambassadorship, after which examples were brought to Europe,[281] as was the sheng (eventually adapted to the harmonica and accordion).[282][283]

- Dominoes: The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) writer Xie Zhaozhe (1567–1624) initiated the legend that dominoes were first presented to the imperial court in 1112.[284] However, the oldest confirmed written mention of dominoes in China comes from the Former Events in Wulin (i.e. the capital Hangzhou) written by the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) author Zhou Mi (1232–1298), who listed "pupai" (gambling plaques or dominoes) as well as dice as items sold by peddlers during the reign of Emperor Xiaozong of Song (r. 1162–1189).[284] Andrew Lo asserts that Zhou Mi meant dominoes when referring to pupai, since the Ming author Lu Rong (1436–1494) explicitly defined pupai as dominoes (in regards to a story of a suitor who won a maiden's hand by drawing out four winning pupai from a set).[284] The earliest known manual written about dominoes is the Manual of the Xuanhe Period (1119–1125) written by Qu You (1347–1433).[284] In the Encyclopedia of a Myriad of Treasures, Zhang Pu (1602–1641) described the game of laying out dominoes as pupai, although the character for pu had changed (yet retained the same pronunciation).[284] Traditional Chinese domino games include Tien Gow, Pai Gow, Che Deng, and others. The thirty-two-piece Chinese domino set (made to represent each possible face of two thrown dice and thus have no blank faces) differs from the twenty-eight-piece domino set found in the Western World during the mid 18th century (in France and Italy).[285] Dominoes first appeared in Italy during the 18th century, and although it is unknown how Chinese dominoes developed into the modern game, it is speculated that Italian missionaries in China may have brought and introduced the game to Europe.[286]

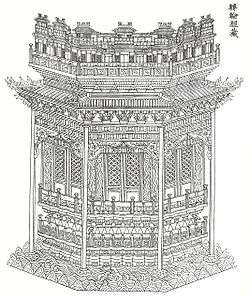

- Dougong: A dougong is a building bracket which is unique to Chinese architecture. Since at least the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 1050–771 BC), they were placed between the top of a column and a crossbeam to support the concave roofs of beam-in-tier buildings which were archetypal of Chinese architecture.[287] Each dougong is formed by double bow-shaped arms (拱, gong) supported by a wooden block (斗, dou) on each side.[287] Dougong were also used for decorative and ceremonial rather than entirely pragmatic purposes of support, such as on solid brick pagodas like the Iron Pagoda built in 1049. The Yingzao Fashi building manual published in 1103 by the Song Dynasty (960–1279) official Li Jie featured illustrations and descriptions of dougong.[288]

- Dragon boats: The use of dragon boats for racing and dragons are believed by modern scholars, sinologists, and anthropologists to have originated in southern central China more than 2500 years ago, in Dongting Lake and along the banks of the Chang Jiang (now called the Yangtze) during the same era when the Olympic games of ancient Greece were being established at Olympia).[289]

- Dragon kiln: Dragon kilns were traditional Chinese kilns used for Chinese ceramics. According to recent excavations in Shangyu District in the northeast of Zhejiang province and elsewhere, the origins of the dragon kiln may go back as far as the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 to 1046 BCE), and is linked to the introduction of stoneware, fired at 1200 °C or more. These kilns were much smaller than later examples, at some 5–12 metres long, and also sloped far less.[290] The type had certainly developed by the Warring States period,[291] and by the Eastern Wu kingdom (220–280 CE), there were over 60 kilns at Shangyu. Thereafter it remained the main design used in southern China until the Ming dynasty. The pottery areas of south China are mostly hilly, whereas those on the plains of north China typically lack suitable slopes; here the mantou kiln type predominated.[292] The Nanfeng Kiln in Guangdong province is several centuries old and still functioning. It was a producer of Shiwan ware as well as architectural ceramics, and today also functions as a tourist attraction.[293]

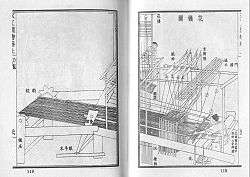

- Drawloom: The earliest confirmed drawloom fabrics come from the State of Chu and date c. 400 BC.[294] Most scholars attribute the invention of the drawloom to the ancient Chinese, although some speculate an independent invention from ancient Syria since drawloom fabrics found in Dura-Europas are thought to date before 256 AD.[294][295] Dieter Kuhn states that an analysis of texts and textiles from the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) proves that the figured fabrics of that era were also crafted with the use of a drawloom.[296] The drawloom was certainly known in Persia by the 6th century AD.[294] Eric Broudy asserts there is virtually no evidence of its use in Europe until the 17th century, while the button drawloom was allegedly invented by Jean le Calabrais in the 15th century.[297] Mary Carolyn Beaudry disagrees, stating that it was used in the medieval Italian silk industry.[296]

- Drilling rig: The technique of percussion drilling for oil and gas originated during the ancient Chinese Han Dynasty in 500 BC, when percussion drilling ("churn drilling") was used to extract natural gas in Sichuan province.[298][298][299] Iron bits were fastened to long bamboo poles, which were centered within a bamboo derrick. The poles were repeatedly hoisted, using cables woven from bamboo fiber. With the assistance of levers, very heavy bits could be raised, of sufficient weight to percussively bore through rock when repeatedly dropped.[298] Han dynasty oil wells were around 10m deep; by the 10th century, depths of 100 meters could be achieved.[298] By the 16th century, Chinese oil prospectors were using percussion drilling to create wells over 2000 feet deep.[299] A modernized variant of the technique was used by American businessman Edwin Drake to drill Pennsylvania's first oil well in 1859, using small steam engines to power the drilling process.[298]

- Dry docks: The use of dry docks in China goes at least as far back the 10th century A.D.[300] In his book Dream Pool Essays, the Song dynasty polymath Shen Kuo wrote of dry docks for repairing ships.[301][302]

E

- Ephedrine: Ephedrine, known as ma huang in traditional Chinese medicine, originally as an extract of the herb Ephedra sinica, has been documented in China since the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) as an antiasthmatic and stimulant.[303] The industrial manufacture of ephedrine in China began in the 1920s, when the American pharmaceutical company Merck began marketing and selling the drug as ephetonin. Ephedrine exports between China and the West grew from 4 tonnes to 216 tonnes between 1926 and 1928.[304]

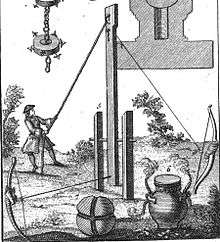

- Escapement, hydraulic-powered (use in clockworks): Although the escapement mechanism was first invented by the Greek Philon of Byzantium for a mechanical washstand,[305] an escapement mechanism for clockworks was first developed by the Buddhist monk, court astronomer, mathematician and engineer Yi Xing (683–727) of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) for his water-powered celestial globe in the tradition of the Han dynasty polymath and inventor Zhang Heng (78–139), and could be found in later Chinese clockworks such as the clock towers developed by the military engineer Zhang Sixun (fl. late 10th century) and polymath inventor Su Song (1020–1101).[154][223][306][307][308][309] Yi Xing's escapement allowed for a bell to be rung automatically every hour, and a drum beaten automatically every quarter-hour, essentially a striking clock.[310] Unlike the modern escapement which employs a suspended oscillating pendulum resting and releasing its hooks on a small rotating gear wheel, the early Chinese escapement employed the use of gravity and hydraulics.[311] In Su Song's clock tower, scoop containers fixed to the spokes of a vertical waterwheel (which acted like a gear wheel) would be filled one by one with siphoned water from a clepsydra tank.[312] When the weight of the water in the scoop filled to an excess, it overcame a counterweight that in turn tripped a lever allowing the scoop to rotate on a pivot and drain its water.[312] However, as the scoop fell, it tripped a coupling tongue that temporarily pulled down on a long vertical chain, the latter yanking down on a balancing lever which would pull upward on a small chain connected to a locking arm, the latter lifting momentarily to release the top arrested spoke before coming back down to repeat the entire process over again.[312] It should be pointed out that the Chinese intermittently working liquid-driven escapement had "only the name in common" with the true mechanical escapement of medieval European mechanical clocks of the 14th century onwards, which worked instead with weights, producing continuous but discrete beats and that derived from the Greek and Roman verge mechanism (alarum) device of earlier mechanisms.[313]

- Exploding cannonballs: The Huolongjing military manual compiled by the Ming dynasty military official Jiao Yu (fl. 14th to early 15th century) and the Ming dynasty military strategist and philosopher Liu Bowen (1311–1375) in the mid 14th century described the earliest known exploding cannonballs, which were made of cast iron with a hollow core packed with gunpowder. Jiao and Liu wrote that when fired, they could set enemy camps ablaze. The earliest evidence for exploding cannonballs in Europe date to the 16th century.[314][315] The Huolongjing also specified the use of poison and blinding gunpowder filled into exploding shells; the effects of this chemical warfare was described as such: "Enemy soldiers will get their faces and eyes burnt, and the smoke will attack their noses, mouths, and eyes."[316]

- Explosives: At its root, the history of chemical explosives lies in the history of gunpowder.[317][318] During the Tang Dynasty in the 9th century, Taoist Chinese alchemists were eagerly trying to find the elixir of immortality.[319] In the process, they stumbled upon the explosive invention of gunpowder made from coal, saltpeter, and sulfur in 1044. Gunpowder was the first form of chemical explosives and by 1161, the Chinese were using explosives for the first time in warfare.[320][321][322] The Chinese would incorporate explosives fired from bamboo or bronze tubes known as bamboo fire crackers. The Chinese also used inserted rats from inside the bamboo fire crackers to fire toward the enemy, creating great psychological ramifications - scaring enemy soldiers away and causing cavalry units to go wild.[323]

F

- Fermented bean curd: According to the 1596 Compendium of Materia Medica written by the Chinese polymath Li Shizhen during the Ming dynasty, the creation of soybean curd is attributed to the Han Dynasty Prince Liu An (179 – 122 BC), king of Huainan. Manufacturing of the bean curd began during the Han Dynasty in China after it was created.[324]

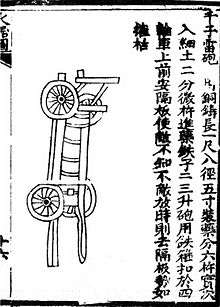

- Field artillery: The medieval Ming dynasty Chinese invented mobile battlefield artillery during the early part of the fourteenth century at the time when gunpowder and the primordial cannon were first being adopted in Europe.[325] One of the earliest documented uses of field artillery is found in the 14th-century Ming Dynasty treatise Huolongjing.[149] The text describes a Chinese cannon called a "thousand ball thunder cannon", manufactured of bronze and fastened with wheels.[149] The book also describes another mobile form of artillery called a "barbarian attacking cannon" consisting of a cannon attached to a two-wheel carriage.[326]

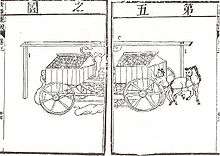

- Field mill: In the Yezhongji ('Record of Affairs at the Capital Ye of the Later Zhao Dynasty') written by Lu Hui (fl. 350 AD), various mechanical devices are described which were invented by two Later Zhao (319–351) engineers known as Xie Fei, a Palace Officer, and Wei Mengbian, the Director of the Imperial Workshops.[327] One of these is the field mill, which was essentially a cart with millstones placed onto the frame; these were mechanically rotated by the movement of the cart's terrain wheels in order to grind wheat and other cereal crops.[328] A similar vehicle these two invented was the "pounding cart", which had wooden statues mounted on the top which were actually mechanical figures who operated real tilt hammers in order to hull rice; again, the device only functioned when the cart was moved forward and the wheels turned.[328] The field mill lost its use in China sometime after the Later Zhao, but it was invented separately in Europe in 1580 by the Italian military engineer Pompeo Targone.[329] It was featured in a treatise by the Italian engineer and writer Vittorio Zonca in 1607, and then in a Chinese book of 1627 (concerning European technology) that was compiled and translated by the German Jesuit polymath Johann Schreck (1576–1630) and the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) Chinese author Wang Zheng (王徵 1571–1644), although by then it was considered by the Chinese to be an original Western contraption.[330]

- Finery forge: In addition to accidental lumps of low-carbon wrought iron produced by excessive injected air in Chinese cupola furnaces, the ancient Chinese also created wrought iron by using the finery forge at least by the 2nd century BC, the earliest specimens of cast and pig iron fined into wrought iron and steel found at the early Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) site at Tieshengguo.[331] Pigott speculates that the finery forge existed in the previous Warring States period (403–221 BC), due to the fact that there are wrought iron items from China dating to that period and there is no documented evidence of the bloomery ever being used in China.[332] The fining process involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation.[331] Wagner writes that in addition to the Han Dynasty hearths believed to be fining hearths, there is also pictoral evidence of the fining hearth from a Shandong tomb mural dated 1st to 2nd century AD, as well as a hint of written evidence in the 4th century AD Daoist text Taiping Jing.[333]

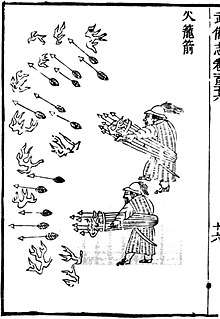

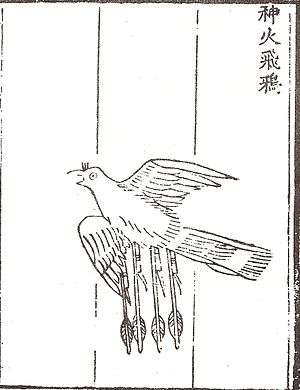

- Fire arrow: One of the earliest weaponized forms of gunpowder was the fire arrow which received its name from the translated Chinese term huǒjiàn (火箭), which literally means fire arrow. In China a 'fire arrow' referred to a gunpowder projectile consisting of a bag of incendiary gunpowder attached to the shaft of an arrow from the 9th century onward. Later on solid fuel rockets utilizing gunpowder were used to provide arrows with propulsive force and the term fire arrow became synonymous with rockets in the Chinese language. In other languages such as Sanskrit 'fire arrow' (agni astra) underwent a different semantic shift and became synonymous with 'cannon.'[334] Fire arrows are the predecessors of fire lances, the first firearm.[335]

- Firecracker: The predecessor of the firecracker was a type of heated bamboo, used as early as 200 BC, that exploded when heated continuously. The Chinese name for firecrackers, baozhu, literally means "exploding bamboo."[336] After the invention of gunpowder, gunpowder firecrackers had a shape that resembled bamboo and produced a similar sound, so the name "exploding bamboo" was retained.[337] In traditional Chinese culture, firecrackers were used to scare off evil spirits.[337]