Cao Cao

| Cao Cao 曹操 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Ming dynasty illustration of Cao Cao in the Sancai Tuhui. | |||||||||||||

| King of Wei (魏王) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 216 – 15 March 220 | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Cao Pi | ||||||||||||

| Duke of Wei (魏公) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 213–216 | ||||||||||||

| Imperial Chancellor (丞相) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 208 – 15 March 220 | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Cao Pi | ||||||||||||

| Minister of Works (司空) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 196–208 | ||||||||||||

| Born |

c. 155 Qiao County, Pei State, Han Empire | ||||||||||||

| Died |

15 March 220 (aged 64–65) Luoyang, Han Empire | ||||||||||||

| Burial |

11 April 220 Cao Cao Mausoleum | ||||||||||||

| Spouse |

| ||||||||||||

| Issue (among others) | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Father | Cao Song | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Lady Ding | ||||||||||||

| Cao Cao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Cao Cao" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 曹操 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

|

Early figures |

|

Founding figures |

|

Later figures |

![]()

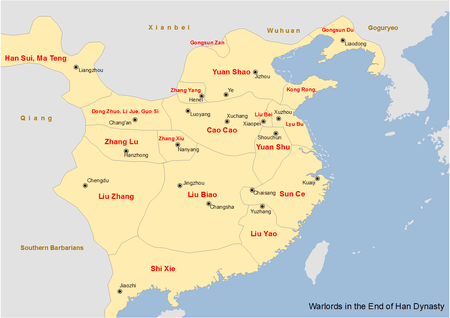

During the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty, Cao Cao was able to secure the most populated and prosperous cities of the central plains and northern China. Cao Cao had much success as the Han chancellor, but his handling of the Han emperor Liu Xie was heavily criticised and resulted in a continued and then escalated civil war. Opposition directly gathered around warlords Liu Bei and Sun Quan, whom Cao Cao was unable to quell.

Cao Cao was also skilled in poetry, calligraphy and martial arts and wrote many war journals.

Early life

Cao Cao was born in Qiao (present-day Bozhou, Anhui) in 155.[2] His father Cao Song was a foster son of Cao Teng, who in turn was one of the favourite eunuchs of Emperor Huan. Some historical records, including the Biography of Cao Man, claim that Cao Song's original family name was Xiahou. However, recent studies show that these records are wrong.

Cao was known for his craftiness as an adolescent. According to the Biography of Cao Man, Cao Cao's uncle complained to Cao Song about Cao Cao's indulgence in hunting and music with Yuan Shao. In retaliation, Cao Cao feigned a fit before his uncle, who immediately rushed to inform Cao Song. When Cao Song went to see his son, Cao Cao behaved normally. When asked, Cao Cao replied, "I have never had a fit, but I lost the love of my uncle, and therefore he deceived you." Afterwards, Cao Song ceased to believe his brother regarding Cao Cao, and thus Cao Cao became even more blatant and insistent in his wayward pursuits.

At that time, there was a man named Xu Shao who lived in Runan and was famous for his ability to evaluate a person's potentials and talents. Cao Cao paid him a visit in hopes of receiving an evaluation that would help him politically. At first, Xu Shao refused to make a statement; however, under persistent questioning, he finally said, "You would be a capable minister in peaceful times and an unscrupulous hero in chaotic times."[3] Cao Cao laughed and left. There are two other versions of this comment in other unofficial historical records.

Early career and Yellow Turban Rebellion (175–188)

At the age of 20, Cao Cao was appointed district captain of Luoyang. Upon taking up the post, he placed rows of multicolored stakes outside his office and ordered his deputies to flog those who violated the law, regardless of their status. An uncle of Jian Shuo, one of the most powerful and influential eunuchs under Emperor Ling, was caught walking in the city after the evening curfew by Cao Cao's men and was flogged. This prompted Jian Shuo and other higher authorities to ostensibly promote Cao Cao to the post of governor of Dunqiu County while actually moving him out of the imperial capital. Cao Cao remained in this position for little more than a year, being dismissed from office in 178 for his distant family ties with the disgraced Empress Song.[4] Around 180, Cao Cao returned to court as a Consultant (議郎) and presented two memoranda against the eunuchs' influence in court and government corruption during his tenure, to limited effect.[2]

When the Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out in 184, Cao Cao was recalled to Luoyang and appointed Captain of the Cavalry (騎都尉) and sent to Yingchuan in Yu Province to suppress the rebels. He was successful and was sent to Ji'nan (濟南) as Chancellor (相) to prevent the spread of Yellow Turban influence there. In Ji'nan, Cao Cao aggressively enforced the ban on unorthodox cults, destroyed shrines, and supported state Confucianism. He offended the local leading families in the process, and resigned on grounds of poor health around 187, fearing that he had put his family in danger.[5] He was offered the post of Administrator of Dong Commandery (東郡), but he declined and returned to his home in Pei County. Around that time, Wang Fen (王芬) tried to recruit Cao Cao to join his coup to replace Emperor Ling with the Marquis of Hefei, but Cao Cao refused. The plot came to nothing, and Wang Fen killed himself.[6]

Alliance against Dong Zhuo (189–191)

| A summary of the major events in Cao Cao's life | |

|---|---|

| 155 | Born in Qiao. |

| 180s | Led troops against Yellow Turban Rebellion in Yingchuan. |

| 190 | Joined the coalition against Dong Zhuo. |

| 196 | Received Emperor Xian in Xuchang. |

| 200 | Won the Battle of Guandu. |

| 208 | Lost the Battle of Red Cliffs. |

| 213 | Created Duke of Wei and given ten commanderies as his dukedom. |

| 216 | Received the title King of Wei. |

| 220 | Died in Luoyang. |

| — | Enthroned posthumously as Emperor Wu. |

After 18 months in retirement, Cao Cao returned to the capital Luoyang in 188. That year, he was appointed Colonel Who Arranges the Army (典軍校尉), fourth of eight heads of a newly established imperial army, the Army of the Western Garden. The effectiveness of this new force was never tested, since it was disbanded the very next year.[7]

In 189, Emperor Ling died and was succeeded by his eldest son (Emperor Shao), although state power was mainly controlled by Empress Dowager He and her advisors. The empress dowager's brother, General-in-Chief He Jin, plotted with Yuan Shao to eliminate the Ten Attendants (a group of influential eunuchs in the imperial court). He Jin summoned Dong Zhuo, a seasoned general of Liang Province, to lead an army into Luoyang to pressure the empress dowager to surrender power, braving accusations of Dong's "infamy". Before Dong Zhuo arrived, He Jin was assassinated by the eunuchs and Luoyang was thrown into chaos as Yuan Shao's supporters fought the eunuchs. Dong Zhuo's army easily rid the palace grounds of opposition. After he deposed Emperor Shao, Dong Zhuo placed the puppet Emperor Xian on the throne, since he deemed that Emperor Xian was more capable than the original puppet Emperor Shao.

After rejecting Dong Zhuo's offer of appointment, Cao Cao left Luoyang for Chenliu (southeast of present-day Kaifeng, Henan, Cao's hometown), where he built an army. The next year, regional warlords formed a military alliance under Yuan Shao against Dong. Cao Cao joined them, becoming one of the few active fighting members of the coalition. The coalition fell apart after months of inactivity, and China fell into civil war while Dong Zhuo was killed in 192 by Lü Bu.

Carving a territory (191–199)

Conquest of Yan Province (191–195)

Through short-term and regional-scale wars, Cao Cao continued to expand his power. In 191, Cao Cao was appointed Administrator of Dong commandery (Dongjun) in Chenliu. This happened after he successfully fought against the bandit chieftain Bo Rao, and Yuan Shao named him Administrator in the stead of the ineffectual Wang Hong. He cleared Dong of bandits, and when the Inspector of Yan Province Liu Dai died the following year, he was invited by Bao Xun and other officers to become the Governor of Yan Province, and deal with an uprising of Yellow Turbans in Qing Province who raided Yan. Despite several setbacks, Cao Cao managed to subdue the rebels by the end of 192, likely through negotiations, and added their 30,000 troops to his army.[8] In early 193, Cao Cao and Yuan Shao fought against the latter's cousin Yuan Shu, driving him away to the River Huai.[8]

Cao Cao's father Cao Song was killed in autumn 193 by troops of Tao Qian, governor of Xu Province (who claimed to be innocent, and that Cao Song's murderers had been mutineers). Enraged, Cao Cao massacred thousands of civilians in Xu during two punitive expeditions in 193 and 194, to avenge his father.[8] Because he took the bulk of his soldiers to Xu Province in order to defeat Tao Qian, most of his territory was left undefended. A number of discontented officers led by Chen Gong and Zhang Chao (Zhang Miao’s brother) plotted to rebel. They convinced Zhang Miao to be their leader, and to ask Lü Bu to come with reinforcements. Chen Gong invited Lü Bu to be the new Inspector of Yan province. Lü Bu accepted this invitation and led his soldiers into the province. Since Cao Cao’s army was away, many of the local commanders figured that fighting would be a lost cause and surrendered to Lü Bu as soon as he arrived. However three counties – Juancheng, Dong’a, and Fan, remained loyal to Cao Cao and when Cao Cao returned, he gathered his own forces at Juancheng.

Throughout 194 and 195, Cao Cao and Lü Bu fought several battles of some size for the control of Yan Province. Though Lü Bu initially did well in holding Puyang, Cao Cao won almost every engagement outside of Puyang. Cao Cao’s decisive victory came in a battle near Dongming. Lü Bu and Chen Gong led a large army to assault Cao Cao’s forces. At that time, Cao Cao was out with a small army, harvesting grain. Seeing Lü Bu and Chen Gong approaching, Cao Cao hid his soldiers in some woods and behind a dam. He then sent a small force ahead to skirmish with Lü Bu’s army. Once the two forces were committed, he unleashed his hidden soldiers. Lü Bu’s army was devastated by this attack and many of his soldiers fled.

Lü Bu and Chen Gong both fled after that battle. Since Xu province was now under Liu Bei’s command and Liu Bei had been Cao Cao’s enemy in the past, they fled to Xu for safety. Cao Cao decided not to pursue them and instead set about crushing Lü Bu’s loyalists in Yan, consolidating his hold over that province. Eighteen months after the rebellion started, Cao had destroyed Zhang Miao and his family, and regained Yan Province by the end of 195.[8]

Securing the emperor (196)

Cao Cao moved his headquarters from Puyang to Xu city (modern Xuchang) in early 196, and built military agricultural colonies for the settlement of refugees, and supply food for his troops.[8]

Around August 196, Emperor Xian returned to Luoyang under the escort of Yang Feng and Dong Cheng. Cao Cao joined Emperor Xian in autumn 196[8] and convinced him to move the capital to Xu city as suggested by Xun Yu and other advisors, as Luoyang was ruined by war and Chang'an was not under Cao's military control. He was appointed Minister of Works (after negotiating with his nominal superior Yuan Shao), and Director of Retainers (司隸 Sī lì), granting him nominal control over Sili Province.[8] Furthermore, he became General-in-Chief (大將軍) and Marquis of Wuping (武平侯), though both titles had little practical application. While some viewed the emperor as a puppet under Cao Cao's control, Cao adhered to a strict personal code until his death that he would not usurp the throne. When he was approached by his advisors to overthrow the Han dynasty and start his own dynasty, he replied, "If heaven bestows such a fate upon me, let me be King Wen of Zhou."[9]

To maintain a good relationship with Yuan Shao, who had become the most powerful warlord in China when he united the northern four provinces, Cao Cao lobbied to have Yuan appointed Minister of Works. However, this had the opposite effect, as Yuan Shao believed that Cao Cao was trying to humiliate him, since Minister of Works technically ranked lower than General-in-Chief, and therefore refused to accept the title. To pacify Yuan Shao, Cao Cao offered his own position to him, while becoming Minister of Works himself. While this temporarily resolved the conflict, it was the catalyst for the Battle of Guandu later.

Battling Zhang Xiu, Liu Biao, and Lü Bu (197–198)

Liu Biao was a major power at that time, holding all of Jing province. Jing had always been prosperous, but it had grown in size because many people fled from the northern wars and sought refuge there. Therefore, Liu Biao constituted a danger to Cao Cao. Zhang Xiu commanded Liu Biao’s territory on the border with Cao Cao, so Cao Cao went to attack him. In 197 Zhang Xiu surrendered to Cao Cao but later attacked his camp in the night (the Battle of Wancheng), killing many people and forcing Cao Cao to flee.

After taking a few months to recover, Cao Cao attacked Yuan Shu’s forces at Ku, claiming more of the man’s land.

Later in 197, Cao Cao returned south to attack Liu Biao/Zhang Xiu once more. This time, Cao Cao was very successful and greatly damaged their army. Cao Cao attacked Zhang Xiu again in 198 leading to the Battle of Rangcheng and was again victorious. He ultimately retreated from this campaign because he received word that Yuan Shao was planning to march on Xu, though this report turned out to be in error.

In April 198, Cao Cao sent envoys to incite the western warlords to attack Chang'an, still controlled by Dong Zhuo's successor Li Jue. One of Li Jue's subordinates, Duan Wei (段煨), mutinied and killed Li Jue along with his family in the summer of 198. Duan Wei sent Li Jue's head to Xu city (as a token of his submission to Cao Cao).[10]

Meanwhile, Lü Bu was growing more aggressive. He drove Liu Bei out of his territory again and allied with Yuan Shu – who had now declared himself Emperor of Zhong. Since Zhang Xiu had recently been crushed, he was in no position to be a threat in the south, so Cao Cao went east to deal with Lü Bu.

Conquest of Xu and Yu Provinces (199)

Cao Cao defeated Lü Bu in numerous battles and eventually surrounded him at Xiapi. Lü Bu tried to break free but could not do so. Ultimately, many of his officers and soldiers defected to Cao Cao. Some were kidnapped by defectors. Lü Bu grew disheartened and surrendered to Cao Cao, who executed him on 7 February 199.[lower-alpha 1] By eliminating Lü Bu, Cao had obtained effective control of Xu Province.[8]

With Lü Bu gone, Cao Cao set about dealing with Yuan Shu. He sent Liu Bei and Zhu Ling south to attack Yuan Shu. However, the false emperor died in the summer of 199 before Liu Bei and the others arrived. This meant Cao Cao had no major opponents in the Huai River region (Yu Province) anymore either.[8] Meanwhile, in March 199 Yuan Shao had finally finished his war with Gongsun Zan at the Battle of Yijing, and was now planning to move south to defeat Cao Cao. Seeing this, Cao Cao set about preparing his defenses, intending to make his stand at Guandu. On the advice of Jia Xu, Zhang Xiu surrendered to Cao Cao and his forces were integrated into Cao Cao's army after they rejected an envoy from Yuan Shao to ally.

Uniting northern China (200–207)

Liu Bei's betrayal and defeat

Near the end of the year 199, Liu Bei betrayed Cao Cao and killed his commanders in Xu Province, claiming to own the province. Cao Cao wanted to attack Liu Bei quickly so as to not get into a two-front war and while some in the court were worried that Yuan Shao would attack them soon if the main army were east, Guo Jia assured Cao Cao that Yuan Shao would be slow to react, and that Cao Cao could handle Liu Bei if he did it quickly. So on Guo Jia's advice, Cao Cao attacked Liu Bei and utterly defeated him in Xu Province, capturing Guan Yu as well as Liu Bei's family members at the start of 200. Liu Bei himself fled to Yuan Shao, who only sent a part of his army to make an attack on Cao Cao. This incursion was stopped by Yu Jin at the Battle of Dushi Ford in February 200, marking the outbreak of open warfare between Cao and Yuan.

War with the Yuan clan

|

|

| China's provinces in 199:

Cao Cao

Others |

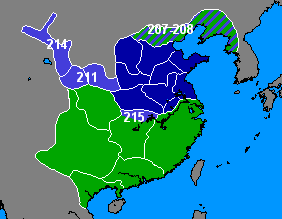

Cao Cao's conquests 207–215:

Cao Cao (206)

Acquisitions

Others |

In 200, Yuan Shao amassed more than 100,000 troops and marched southwards on Xuchang in the name of rescuing the emperor. Cao Cao gathered 20,000 men in Guandu, a strategic point on the Yellow River. The two armies came to a standstill as neither side was able to make much progress. Cao Cao's lack of men did not allow him to make significant attacks, and Yuan Shao's pride forced him to meet Cao's force head-on. Despite his overwhelming advantage in terms of manpower, Yuan Shao was unable to make full use of his resources because of his indecisive leadership and Cao Cao's position.

Besides the middle battleground of Guandu, two lines of battle were present. The eastern line with Yuan Tan of Yuan Shao's army against Zang Ba of Cao Cao's army was a one-sided battle in favour of Cao, as Yuan Tan's poor leadership was no match for Zang's local knowledge of the landscape and his hit-and-run tactics. On the western front, Yuan Shao's nephew, Gao Gan, performed better against Cao Cao's army and forced several reinforcements from Cao's main camp to maintain the western battle. Liu Bei, then a guest in Yuan Shao's army, suggested that he instigate rebellion in Cao Cao's territories as many followers of Yuan were in Cao's lands. The tactic was initially successful but Man Chong's diplomatic skills helped to resolve the conflict almost immediately. Man Chong had been placed as an official there for this specific reason, as Cao Cao had foreseen the possibility of insurrection prior to the battle. Finally, a defector from Yuan Shao's army, Xu You, informed Cao Cao of the location of Yuan's supply depot. Cao Cao broke the stalemate by sending a special group of soldiers to burn all the supplies of Yuan Shao's army, thus winning a decisive and seemingly impossible victory.

Yuan Shao fell ill and died shortly after the defeat in 202, leaving two sons – the eldest son, Yuan Tan and the youngest son, Yuan Shang. As he had designated the youngest son, Yuan Shang, as his successor, rather than the eldest as tradition dictated, the two brothers fought each other, as they fought Cao Cao. Cao Cao used the internal conflict within the Yuan clan to his advantage and defeated the Yuans easily. Gao Gan, governor of Bing Province, defected to Cao Cao in 203. The province of Ji fell to Cao Cao in 204 after the long siege of Ye, the Yuans' capital city. In January and February 205, Cao Cao battled Yuan Tan at Nanpi, and conquered Qing Province. Gao Gan rebelled in 205, but in 206 Cao Cao defeated and killed him, annexing Bing definitively.

Cao Cao assumed effective rule over all of northern China, but Yuan Shang and Yuan Xi had fled to the Wuhuan chieftains for aid after a defect in 206 to Cao Cao. In 207, Cao Cao led a daring campaign beyond Chinese borders in hopes of destroying the Yuan’s once and for all. He fought an alliance of Wuhuan chieftains at White Wolf Mountain. Though outnumbered and isolated, Cao Cao emerged victorious. He killed a number of the Wuhuan chiefs and forced the Yuans to flee once again. This time, they went to Gongsun Kang for help, but he executed them and sent their heads to Cao Cao, granting him nominal control over You Province. Meanwhile, the northern tribes were now terrified of Cao Cao. Most of the remaining Wuhuan submitted to him, along with the Xianbei and Xiongnu.

Red Cliffs campaign (208–210)

Nevertheless, Cao Cao's attempt to extend his domination south of the Yangtze River was unsuccessful. He received an initial success when Liu Biao, the Governor of Jing Province, died, and his successor, Liu Cong surrendered to Cao Cao without resistance.[13] Delighted by this, he pressed on despite objections from his military advisors and hoped the same would happen again. His forces were defeated by a coalition of his arch-rivals Liu Bei and Sun Quan (who later founded the states of Shu Han and Eastern Wu respectively) at the Battle of Red Cliffs in 208.[13]

Throughout 209 and 210, Cao Cao’s commanders were engaged in defensive efforts against Sun Quan. In battles at Jiangling and Yiling, Cao Cao's commanders in northern Jing fought against Sun Quan. They experienced mixed success, and Cao Cao was able to retain some territory in the north of that province. At the same time, they held off an attack on Hefei and put down a revolt in Lu that Sun Quan's forces tried to assist, keeping Sun Quan from moving to attack Shouchun. However, Cao Cao's commanders in southern Jing, cut off from the rest of Cao Cao’s forces, surrendered to Liu Bei.

Campaigns in the northwest (211–220)

By 211, the situation in the south had stabilized and Cao Cao decided to crush his remaining enemies in the north. In Hanzhong commandery, in the north of Yi Province, Zhang Lu lived in revolt against the Han, running his own theocratic state. Cao Cao sent Zhong Yao with an army to force Zhang Lu’s surrender. A number of warlords in Liang Province however united under Han Sui and Ma Chao to oppose Cao Cao, believing that his maneuvers against Zhang Lu were actually directed at them. Cao Cao personally led the army against this alliance. In the Battle of Tong Pass Cao Cao outmaneuvered the rebel army at every turn. The alliance shattered and many of the leaders were killed. Cao Cao spent the next month or two hunting down some of the leaders, many of whom surrendered to him. He then returned home and left Xiahou Yuan to clear up affairs in the region.

In 213, Cao Cao received the title "Duke of Wei" (魏公) and was given the nine bestowments and a fief of ten cities under his domain, known as Wei. That same year, he marched south and attacked Ruxu. Sun Quan's general Lü Meng held off the attacks for about a month, and Cao Cao had to pull back in the end. In 215, Cao Cao moved into and took over Hanzhong. In 216, Cao Cao was promoted to the status of a vassal king – "King of Wei" (魏王). Over the years, Cao Cao, as well as Liu Bei and Sun Quan, continued to consolidate their power in their respective regions. Through many wars, China became divided into three powers – Wei, Shu and Wu, which fought sporadic battles without the balance tipping significantly in anyone's favour. The only exception was when Liu Bei's forces were able to take Hanzhong from Cao Cao's army after a campaign that took two years.

Death

In 220, Cao Cao died in Luoyang at the age of 65, having failed to unify China under his rule. His will instructed that he be buried near Ximen Bao's tomb in Ye without gold and jade treasures, and that his subjects on duty at the frontier were to stay in their posts and not attend the funeral as, in his own words, "the country is still unstable".

Cao Cao's eldest surviving son Cao Pi succeeded him. Within a year, Cao Pi forced Emperor Xian to abdicate and proclaimed himself the first emperor of the state of Cao Wei. Cao Cao was then posthumously titled "Grand Ancestor Emperor Wu of Wei" (魏太祖武皇帝)

Cultural legacy

While historical records indicate Cao Cao as a brilliant ruler, he was represented as a cunning and deceitful man in Chinese opera, where his character is given a white facial makeup to reflect his treacherous personality. When Luo Guanzhong wrote the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, he took much of his inspiration from Chinese opera.

As a result, depictions of Cao Cao as unscrupulous have become much more popular among the common people than his real image. There have been attempts to revise this depiction.[14][15]

As the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms has been adapted to modern forms of entertainment, so has its portrayal of Cao Cao. Given the source material upon which these adaptations are founded, Cao Cao continues to be characterised as a prominent villain.

Through to modern times, the Chinese equivalent of the English idiom "speak of the Devil" is "speak of Cao Cao and Cao Cao arrives" (simplified Chinese: 说曹操,曹操到; traditional Chinese: 說曹操,曹操到; pinyin: shuō Cáo Cāo, Cáo Cāo dào).

After the Communists won the Chinese Civil War in 1949, many people in China began to believe that there were many similarities between Cao Cao and Mao Zedong. Because of this perceived similarity, propagandists began a long-term, sustained effort to improve the image of Cao Cao in Chinese popular culture. In 1959, Peng Dehuai wrote a letter to Mao, in which he compared himself to Zhang Fei: because of Mao's popular association with Cao, Peng's comparison implied that he had an intuitively confrontational relationship with Mao. Mao had the letter widely circulated in order to make Peng's attitude clear to other Party members, and proceeded to purge Peng, eventually ending Peng's career.[16]

Agriculture and education

While waging military campaigns against his enemies, Cao Cao did not forget the bases of society – agriculture and education.

In 194, a locust plague caused a major famine across China. The people resorted to cannibalism out of desperation. Without food, many armies were defeated without fighting. From this experience, Cao Cao saw the importance of an ample food supply in building a strong military. He began a series of agricultural programs in cities such as Xuchang and Chenliu. Refugees were recruited and given wasteland to cultivate. Later, encampments not faced with imminent danger of war were also made to farm. This system was continued and spread to all regions under Cao Cao as his realm expanded. Although Cao Cao's primary intention was to build a powerful army, the agricultural program also improved the living standards of the people, especially war refugees.

By 203, Cao Cao had eliminated most of Yuan Shao's forces. This afforded him more attention on construction within his realm. In autumn of that year, Cao Cao passed an order decreeing the promotion of education throughout the counties and cities within his jurisdiction. An official in charge of education was assigned to each county with more than 500 households. Youngsters with potential and talent were selected for schooling. This prevented a lapse in the training of intellectuals in those years of war, and, in Cao Cao's words, would benefit the people.

Poetry

Cao Cao was an accomplished poet, as were his sons Cao Pi and Cao Zhi. He was also a patron of poets such as Xu Gan.[17] Of Cao Cao's works, only a remnant remain today. His verses, unpretentious yet profound, helped to reshape the poetic style of his time and beyond, eventually contributing to the poetry styles associated with Tang dynasty poetry. Cao Cao, Cao Pi and Cao Zhi are known collectively as the "Three Caos". The Three Caos' poetry, together with additional poets, became known as the Jian'an style, which contributed eventually to Tang and later poetry. Cao Cao also wrote verse in the older four-character per line style characteristic of the Classic of Poetry. Burton Watson describes Cao Cao as: "the only writer of the period who succeeded in infusing the old four-character metre with any vitality, mainly because he discarded the archaic diction associated with it and employed the ordinary poetic language of his time."[18] Cao Cao is also known for his early contributions to the Shanshui poetry genre, with his 4-character-per-line, 14-line poem "View of the Blue Sea" (觀滄海).[19]

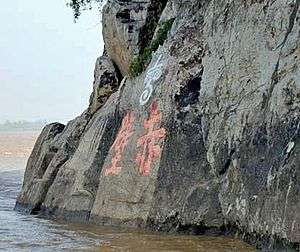

Mausoleum

On 27 December 2009, the Henan Provincial Cultural Heritage Bureau reported the discovery of Cao Cao's tomb in Xigaoxue Village, Anyang County, Henan. The tomb, covering an area of 740 square metres, was discovered in December 2008 when workers at a nearby kiln were digging for mud to make bricks. Its discovery was not reported and the local authorities knew of it only when they seized a stone tablet carrying the inscription 'King Wu of Wei' — Cao Cao's posthumous title — from grave robbers who claimed to have stolen it from the tomb. Over the following year, archaeologists recovered more than 250 relics from the tomb. The remains of three persons — a man in his 60s, a woman in her 50s and another woman in her 20s — were also unearthed and are believed to be those of Cao Cao, one of his wives, and a servant.[20]

Since the discovery of the tomb, there have been many skeptics and experts who pointed out problems with it and raised doubts about its authenticity.[21] In January 2010, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage legally endorsed the initial results from research conducted throughout 2009 suggesting that the tomb was Cao Cao's.[22] However, in August 2010, 23 experts and scholars presented evidence at a forum held in Suzhou, Jiangsu to argue that the findings and the artifacts of the tomb were fake.[23] In September 2010, an article published in an archaeology magazine claimed that the tomb and the adjacent one actually belonged to Cao Huan (a grandson of Cao Cao) and his father Cao Yu.[24]

In 2010, the tomb became part of the fifth batch of Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level in China.[25] As of December 2011, it has been announced that the local government in Anyang is constructing a museum on the original site of the tomb which will be named 'Cao Cao Mausoleum Museum' (曹操高陵博物馆).[26]

Media reports from 2018 describe the tomb complex as having an outer rammed earth foundation, a spirit way, and structures on the east and south sides. Archaeologists have also noted that the tomb's exterior and perimeter appear to be deliberately left unmarked; there are neither structures above the ground around the tomb nor massive piles of debris in the vicinity. This indirectly confirms historical records that Cao Pi had ordered the monuments on the surface to be systematically dismantled to honour his father's wishes to be buried in a simple manner in a concealed location, as well as to prevent tomb robbers from finding and looting the tomb.[27][28][29][30]

In Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a historical novel by Luo Guanzhong, was a romanticisation of the events that occurred in the late Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period. While adhering to historical facts most of the time, the novel inevitably reshaped Cao Cao to some extent, so as to portray him as a cruel and suspicious villain. In some chapters, Luo created fictional or semi-fictional events involving Cao Cao.

See the following for some fictitious stories in Romance of the Three Kingdoms involving Cao Cao:

- List of fictitious stories in Romance of the Three Kingdoms § Cao Cao presents a precious sword

- List of fictitious stories in Romance of the Three Kingdoms § Cao Cao arrested and released by Chen Gong

- Lü Boshe

- List of fictitious stories in Romance of the Three Kingdoms § Guan Yu releases Cao Cao at Huarong Trail

- List of fictitious stories in Romance of the Three Kingdoms § New Book of Mengde

- Battle of Tong Pass (211) § In fiction

- List of fictitious stories in Romance of the Three Kingdoms § Cao Cao's death

In popular culture

Film and television

The "Father of Hong Kong cinema", Lai Man-Wai, played Cao Cao in The Witty Sorcerer, a 1931 comedy film based on the story of Zuo Ci playing tricks on Cao Cao. In the Shaw Brothers film The Weird Man, Cao Cao was seen in the beginning of the film with Zuo Ci. Zuo Ci was playing tricks on him by giving him a tangerine with no fruit inside. This was later referenced in another film titled Five Element Ninjas.

Other notable actors who have portrayed Cao Cao in film and television include:

- Bao Guo'an, in the 1994 Chinese television series Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Bao won two Best Actor awards at the 1995 Golden Eagle Awards and Flying Apsaras Awards for his performance.

- Damian Lau, in the 2008 Hong Kong film Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon.

- Zhang Fengyi, in the 2008–09 Chinese film Red Cliff.

- Chen Jianbin, in the 2010 Chinese television series Three Kingdoms.

- Jiang Wen, in the 2011 Hong Kong film The Lost Bladesman and the 2018 Chinese television series Cao Cao.

- Chow Yun-fat, in the 2012 Chinese film The Assassins.

- Zhao Lixin, in the 2014 Chinese television series Cao Cao.

- Yu Hewei, in the 2017 Chinese television series The Advisors Alliance.

- Tse Kwan-ho, in the 2018 Chinese television series Secret of the Three Kingdoms.

- Wang Kai, in the upcoming Hong Kong film Dynasty Warriors.

Card games

In the selection of hero cards in the Chinese card game San Guo Sha (三国杀), there is also a Cao Cao hero that players can select at the beginning of the game.

Cao Cao is also referenced in Magic: The Gathering, as the card "Cao Cao, Lord of Wei". This card is black, the colour representing ruthlessness and ambition, though not necessarily evil. It was first printed in Portal Three Kingdoms and again in From the Vault: Legends.

Video games

Cao Cao appears in Koei's Romance of the Three Kingdoms video game series. He is also featured as a playable character in Koei's Dynasty Warriors and Warriors Orochi series. He also features in Koei's Kessen II as a playable main character.

Cao Cao also appears in Puzzle & Dragons as part of the Three Kingdoms Gods series.[31]

Cao Cao appears as a Great Person in Civilization IV and later as a Great General in Civilization V.

Cao Cao appears in Creative Assembly's Total War: Three Kingdoms.

Other appearances

As with most of the other relevant generals of the period, Cao Cao is portrayed as a young female character in the Koihime Musō franchise. He is also the central character in the Japanese manga series Sōten Kōro. Barry Hughart's novel The Story of the Stone mentions the Seven Sacrileges of Tsao Tsao, most of which involve family.[32]

Family

- Parents:

- Cao Song (太皇帝 曹嵩; d. 193)

- Lady Ding (丁氏)

- Consorts and Issue:

- Lady Ding (夫人 丁氏; d. 219)

- Lady Bian (武宣皇后 卞氏; 161 – 230)

- Lady Liu (夫人 劉氏)

- Cao Ang (豐愍王 曹昂; 178 – 197)

- Cao Shuo (相殤王 曹鑠)

- Princess Qinghe (清河公主), m. Xiahou Mao

- Lady Huan (夫人 環氏)

- Lady Du (夫人 杜氏)

- Lady Qin (夫人 秦氏)

- Lady Yin (夫人 尹氏)

- Cao Ju (范陽閔王 曹矩)

- Lady Sun (孫氏)

- Lady Li (李氏)

- Lady Zhou (週氏)

- Cao Jun (樊安公 曹均; d. 219)

- Lady Chen (陳氏)

- Cao Gan (趙王 曹幹; 214 – 261)

- Lady Liu (劉氏)

- Cao Ji (廣宗殤公 曹棘)

- Lady Song (宋氏)

- Cao Hui (東平靈王 曹徽; d. 242)

- Lady Zhao (趙氏)

- Cao Mao (樂陵王 曹茂)

- Unknown

- Lady Cao (曹憲), m. Liu Xie, personal name Xian

- Princess Anyang (安陽公主)

Research on ancestry

Cao Cao was a purported descendant of the Western Han dynasty chancellor Cao Shen. In the early 2010s, researchers from Fudan University compared the Y chromosomes collected from a tooth from Cao Cao's granduncle, Cao Ding (曹鼎), with those of Cao Shen and found them to be significantly different. Therefore, the claim about Cao Cao descending from Cao Shen was not supported by genetic evidence.[33] The researchers also found that the Y chromosomes of Cao Ding match those of self-proclaimed living descendants of Cao Cao who hold lineage records dating back to more than 100 generations ago.[34]

Zhu Ziyan, a history professor from Shanghai University, felt that Cao Ding's tooth alone cannot be used as evidence to determine Cao Cao's ancestry. He was sceptical about whether those who claim to be Cao Cao's descendants are really so, because genealogical records dating from the Song dynasty (960–1279) are already so rare in the present day, much less those dating from the Three Kingdoms era (220–280). Besides, according to historical records, Cao Ding was a younger brother of the eunuch Cao Teng, who adopted Cao Cao's biological father, Cao Song. Therefore, Cao Cao had no known blood relations with Cao Ding. In other words, Cao Ding was not Cao Cao's real granduncle (this assuming that there was no intra-family adoption, which was actually common in China). Zhu Ziyan mentioned that Fudan University's research only proves that those self-proclaimed descendants of Cao Cao are related to Cao Ding; it does not directly relate them to Cao Cao.[35]

See also

Notes

- ↑ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 35,38.

- 1 2 de Crespigny (2010), p. 35

- ↑ (治世之能臣,乱世之奸雄。) Chen Shou. Records of Three Kingdoms, Volume 1, Biography of Cao Cao.

- ↑ de Crespigny (2010), pp. 33–34

- ↑ de Crespigny (2010), p. 39

- ↑ de Crespigny (2010), p. 40

- ↑ de Crespigny (2010), p. 43

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 de Crespigny, Rafe (2006). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23-220 AD). Leiden: Brill. p. 35–39. ISBN 9789047411840. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ (若天命在吾,吾为周文王矣。) Chen Shou. Records of Three Kingdoms, Volume 1, Biography of Cao Cao. King Wen was a high official at the end of the Shang dynasty in ancient China. At the time, the corruption of King Zhou of Shang prompted many uprisings, including that of King Wen; but King Wen insisted that he would not take the throne himself as it is improper for him, a subordinate, to harm the Shang dynasty. Instead, he allowed his son (King Wu of Zhou) to destroy the Shang dynasty and establish the Zhou dynasty after his own death, and thus fulfilling his personal code of honour but also ridding the world of a terrible ruler. He was then named King Wen of Zhou posthumously by King Wu of Zhou. Here, Cao Cao was inferring that if the Cao family were to come to power and establish a new dynasty, it would be by his descendants and not him.

- ↑ de Crespigny, Rafe (2006), p. 418.

- ↑ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 624-625.

- ↑ ([侯]成忿懼,十二月,癸酉,成與諸將宋憲、魏續等共執陳宮、高順,率其衆降。[呂]布與麾下登白門樓。兵圍之急,布令左右取其首詣[曹]操,左右不忍,乃下降。 ... 宮請就刑,遂出,不顧,操為之泣涕,幷布、順皆縊殺之,傳首許市。操召陳宮之母,養之終其身,嫁宮女,撫視其家,皆厚於初。) Zizhi Tongjian vol. 62.

- 1 2 de Crespigny, Rafe (2016). Fire over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty 23-220 AD. Leiden: Brill. p. 472. ISBN 9789004325203. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "亦有可聞:魏延為何負上「叛徒」罵名 – 香港文匯報". Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ "谭其骧与郭沫若的学术论争". gmw.cn. Archived from the original on 10 February 2005. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ Domes 91

- ↑ Davis, p. vi

- ↑ Watson, p. 38

- ↑ Yip, 130–33

- ↑ Lin, Shujuan (28 December 2009). "Tomb of legendary ruler unearthed". China Daily. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Zhang, Zhongjiang (29 December 2009). "学者称曹操墓葬确认在河南安阳证据不足 [Experts say there is insufficient evidence to confirm that Cao Cao's tomb is in Anyang, Henan]" (in Chinese). Tengxun News. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Wang, Yun (29 January 2010). "国家文物局认定河南安阳东汉大墓墓主为曹操 [SACH confirms that the Eastern Han tomb in Anyang, Henan belonged to Cao Cao]" (in Chinese). Tengxun News. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ Jiang, Wanjuan (24 August 2010). "Cao Cao's tomb: Experts reveal that findings and artifacts are fake". Global Times. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ "安阳西高穴应为曹奂墓,"曹操墓"尴尬收场(图) [The Xigaoxue tomb in Anyang should be that of Cao Huan. "Cao Cao Tomb" comes to an awkward end. (pictured)]" (in Chinese). 360doc.com. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Yang, Yuguo (3 May 2013). "河南曹操高陵少林寺入选全国重点文物保护单位 [Henan's Cao Cao Mausoleum and Shaolin Monastery are selected to be Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level]" (in Chinese). CRI online. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ "曹操高陵开启新的篇章 安阳将原址建博物馆 [A new chapter opens for the Cao Cao Mausoleum. Anyang government will build a museum on the original site.]" (in Chinese). chinahuanqiu.com. 28 December 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Everington, Keoni (26 March 2018). "Tomb of legendary Chinese general Cao Cao found". Taiwan News. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Zhou, Laura (26 March 2018). "Archaeologists confident they have found body of fabled Chinese warlord Cao Cao". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "梟雄出土 河南考古找到曹操遺骸 [A xiaoxiong is unearthed; Henan archaeologists discover Cao Cao's remains]". Apple Daily (in Chinese). 25 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Archaeologists claim to have found body of China's Cao Cao". Mirage News. 27 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Cao Cao stats, skills, evolution, location | Puzzle & Dragons Database". puzzledragonx.com. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ↑ Hughart, Barry (1988). The Story of the Stone. Doubleday. pp. 13, 55.

- ↑ Wang CC, Yan S, Hou Z, Fu W, Xiong M, Han S, Jin L, Li H. Present Y chromosomes reveal the ancestry of Emperor CAO Cao of 1800 years ago. J Hum Genet. 2012, 57(3):216–18.

- ↑ Chuan-Chao Wang; Shi Yan; Can Yao; Xiu-Yuan Huang; Xue Ao; Zhanfeng Wang; Sheng Han; Li Jin; Hui Li (14 February 2013). "Ancient DNA of Emperor CAO Cao's granduncle matches those of his present descendants: a commentary on present Y chromosomes reveal the ancestry of Emperor CAO Cao of 1800 years ago". Journal of Human Genetics. The Japan Society of Human Genetics. 58 (4): 238–39. doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.5. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "上海學者商榷復旦曹操DNA研究:僅憑曹鼎牙齒難揭身世 [Scholars from Shanghai (University) discuss Fudan (University)'s research on Cao Cao's DNA: A tooth from Cao Ding is insufficient to determine (Cao Cao's) ancestry]". Sina News (in Chinese). 11 December 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ (太祖一名吉利,小字阿瞞。) Pei Songzhi's annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 1.

- ↑ The Australian sinologist Rafe de Crespigny wrote in A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms 23-220 AD that Lü Bu died in the year 198.[11] This date is incorrect even though the 3rd year of the Jian'an era of the reign of Emperor Xian of Han largely corresponds to the year 198 in the Gregorian calendar. That is because the 11th month of the 3rd year of Jian'an was from 16 December 198 to 14 January 199 in the Gregorian calendar, so the 12th month was already into the year 199. The Zizhi Tongjian recorded that Lü Bu surrendered to Cao Cao on the guiyou day of the 12th month of the 3rd year of the Jian'an era. He was executed on the same day.[12] This date corresponds to 7 February 199 in the Gregorian calendar.

References

- Chen Shou (2002). Records of Three Kingdoms. Yue Lu Shu She. ISBN 7-80665-198-5.

- Domes, Jurgen. Peng Te-huai: The Man and the Image, London: C. Hurst & Company. 1985. ISBN 0-905838-99-8.

- A. R. (Albert Richard) Davis, Editor and Introduction (1970). The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse. Penguin Books.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms 23–220 AD. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004156050.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2010). Imperial warlord : a biography of Cao Cao 155-220 AD. Leiden Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18522-7.

- Luo Guanzhong (1986). Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Yue Lu Shu She. ISBN 7-80520-013-0.

- Lo Kuan-chung; tr. C.H. Brewitt-Taylor (2002). Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3467-9.

- Sun Tzu (1983). The Art of War. Delta. ISBN 0-440-55005-X.

- Burton Watson (1971). CHINESE LYRICISM: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03464-4.

- Yi Zhongtian (2006). Pin San Guo (品三國; Analysis of the Three Kingdoms). Joint Publishing (H.K.) Co., Ltd. ISBN 978-962-04-2609-4.

- Yip, Wai-lim (1997). Chinese Poetry: An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres. (Durham and London: Duke University Press). ISBN 0-8223-1946-2

External links

- Cao Cao – Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Works by or about Cao Cao at Internet Archive

- Works by Cao Cao at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Emperor Wu of Cao Wei Born: 155 Died: 15 March 220 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Himself as Duke of Wei |

King of Wei 216–220 |

Succeeded by Cao Pi |

| Political offices | ||

| Vacant Title last held by Dong Zhuoas Chancellor of State |

Imperial Chancellor Eastern Han 208–220 |

Succeeded by Cao Pi |

| Chinese nobility | ||

| New title | Duke of Wei 213–216 |

Succeeded by Himself as King of Wei |