History of paper

Paper, a thin unwoven material made from milled plant fibers, is primarily used for writing, artwork, and packaging; it is commonly white. The first papermaking process was documented in China during the Eastern Han period (25–220 AD), traditionally attributed to the court official Cai Lun. During the 8th century, Chinese papermaking spread to the Islamic world, where pulp mills and paper mills were used for papermaking and money making. By the 11th century, papermaking was brought to Europe. By the 13th century, papermaking was refined with paper mills utilizing waterwheels in Spain. Later European improvements to the papermaking process came in the 19th century with the invention of wood-based papers.

Although precursors such as papyrus and amate existed in the Mediterranean world and pre-Columbian Americas, respectively, these materials are not defined as true paper. Nor is true parchment considered paper[lower-alpha 1]; used principally for writing, parchment is heavily prepared animal skin that predates paper and possibly papyrus. In the twentieth century with the advent of plastic manufacture some plastic "paper" was introduced, as well as paper-plastic laminates, paper-metal laminates, and papers infused or coated with different products that give them special properties.

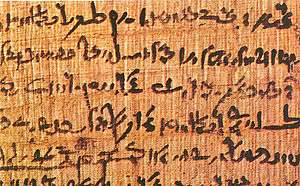

Precursors: papyrus

The word "paper" is etymologically derived from papyrus, Ancient Greek for the Cyperus papyrus plant. Papyrus is a thick, paper-like material produced from the pith of the Cyperus papyrus plant which was used in ancient Egypt and other Mediterranean societies for writing long before paper was used in China.[1]

Papyrus is prepared by cutting off thin ribbon-like strips of the interior of the Cyperus papyrus, and then laying out the strips side-by-side to make a sheet. A second layer is then placed on top, with the strips running at right angle to the first. The two layers are the pounded together into a sheet. The result is very strong, but has an uneven surface, especially at the edges of the strips. When used in scrolls, repeated rolling and unrolling causes the strips to come apart again, typically along vertical lines. This effect can be seen in many ancient papyrus documents.[2]

Paper contrasts with papyrus in that the plant material is broken down through maceration or disintegration before the paper is pressed. This produces a much more even surface, and no natural weak direction in the material which falls apart over time.[3]

It is lucky chance that the date of CE 105 was recorded, because Cai Lun, the official involved, who seems to have introduced some improvements in paper manufacture, worked at the palace as a eunuch. Yet just because the new technology was not trumpeted at the time does not mean that it had no effect. On the contrary: up to this point China was lagging behind those Mediterranean societies where papyrus was used and where light, inexpensive scrolls could be created. But thereafter the advantage swung the other way, since papyrus, which is composed of organic material not as highly processed as paper, was prone to splitting and deterioration at a much greater rate; this may be why vellum eventually came to dominate, especially in the harsher climate of Northern Europe. Paper, by contrast, gave a good, uniform writing surface that could be smoothly rolled and unrolled without damage, while remaining relatively durable.[4]

— T.H. Barrett

Paper in China

Archaeological evidence of papermaking predates the traditional attribution given to Cai Lun,[5] an imperial eunuch official of the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220), thus the exact date or inventor of paper can not be deduced. The earliest extant paper fragment was unearthed at Fangmatan in Gansu province, and was likely part of a map, dated to 179–141 BC.[6] Fragments of paper have also been found at Dunhuang dated to 65 BC and at Yumen pass, dated to 8 BC.[7]

"Cai Lun's" invention, recorded hundreds of years after it took place, is dated to 105 AD. The innovation is a type of paper made of mulberry and other bast fibres along with fishing nets, old rags, and hemp waste which reduced the cost of paper production, which prior to this, and later, in the West, depended solely on rags.[7][8][4]

Techniques

During the Shang (1600–1050 BC) and Zhou (1050–256 BC) dynasties of ancient China, documents were ordinarily written on bone or bamboo (on tablets or on bamboo strips sewn and rolled together into scrolls), making them very heavy, awkward, and hard to transport. The light material of silk was sometimes used as a recording medium, but was normally too expensive to consider. The Han dynasty Chinese court official Cai Lun (c. 50–121) is credited as the inventor of a method of papermaking (inspired by wasps and bees) using rags and other plant fibers in 105 AD.[4] However, the discovery of specimens bearing written Chinese characters in 2006 at Fangmatan in north-east China's Gansu Province suggests that paper was in use by the ancient Chinese military more than 100 years before Cai, in 8 BC, and possibly much earlier as the map fragment found at the Fangmatan tomb site dates from the early 2nd century BC.[6] It therefore would appear that "Cai Lun's contribution was to improve this skill systematically and scientifically, fix a recipe for papermaking".[9]

The record in the Twenty-Four Histories says[10]

- In ancient times writings and inscriptions were generally made on tablets of bamboo or on pieces of silk called chih. But silk being costly and bamboos heavy they were not convenient to use. Tshai Lun then initiated the idea of making paper from the bark of trees, remnants of hemp, rags of cloth and fishing nets. He submitted the process to the emperor in the first year of Yuan-Hsing (105 AD) and received praise for his ability. From this time, paper has been in use everywhere and is universally called the paper of Marquis Tshai.

The production process may have originated from the practice of pounding and stirring rags in water, after which the matted fibres were collected on a mat. The bark of Paper Mulberry was particularly valued and high quality paper was developed in the late Han period using the bark of tan (檀; sandalwood). In the Eastern Jin period a fine bamboo screen-mould treated with insecticidal dye for permanence was used in papermaking. After printing was popularized during the Song dynasty the demand for paper grew substantially. In the year 1101, 1.5 million sheets of paper were sent to the capital.[10]

Uses

Open, it stretches; closed, it rolls up. it can be contracted or expanded; hidden away or displayed.[7]

— Fu Xian

Among the earliest known uses of paper was padding and wrapping delicate bronze mirrors according to archaeological evidence dating to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han from the 2nd century BC.[11] Padding doubled as both protection for the object as well as the user in cases where poisonous "medicine" were involved, as mentioned in the official history of the period.[11] Although paper was used for writing by the 3rd century AD,[12] paper continued to be used for wrapping (and other) purposes. Toilet paper was used in China from around the late 6th century.[13] In 589, the Chinese scholar-official Yan Zhitui (531–591) wrote: "Paper on which there are quotations or commentaries from Five Classics or the names of sages, I dare not use for toilet purposes".[13] An Arab traveler who visited China wrote of the curious Chinese tradition of toilet paper in 851, writing: "... [the Chinese] do not wash themselves with water when they have done their necessities; but they only wipe themselves with paper".[13]

During the Tang dynasty (618–907) paper was folded and sewn into square bags to preserve the flavor of tea. In the same period, it was written that tea was served from baskets with multi-colored paper cups and paper napkins of different size and shape.[11] During the Song dynasty (960–1279) the government produced the world's first known paper-printed money, or banknote (see Jiaozi and Huizi). Paper money was bestowed as gifts to government officials in special paper envelopes.[13] During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), the first well-documented Europeans in Medieval China, the Venetian merchant Marco Polo remarked how the Chinese burned paper effigies shaped as male and female servants, camels, horses, suits of clothing and armor while cremating the dead during funerary rites.[14]

Impact of paper

According to Timothy Hugh Barrett, paper played a pivotal role in early Chinese written culture, and a "strong reading culture seems to have developed quickly after its introduction, despite political fragmentation."[15] Indeed the introduction of paper had immense consequences for the book world. It meant books would no longer have to be circulated in small sections or bundles, but in their entirety. Books could now be carried by hand rather than transported by cart. As a result individual collections of literary works increased in the following centuries.[16]

Textual culture seems to have been more developed in the south by the early 5th century, with individuals owning collections of several thousand scrolls. In the north an entire palace collection might have been only a few thousand scrolls in total.[17] By the early 6th century, scholars in both the north and south were capable of citing upwards of 400 sources in commentaries on older works.[18] A small compilation text from the 7th century included citations to over 1,400 works.[19]

The personal nature of texts was remarked upon by a late 6th century imperial librarian. According to him, the possession of and familiarity with a few hundred scrolls was what it took to be socially accepted as an educated man.[20]

According to Endymion Wilkinson, one consequence of the rise of paper in China was that "it rapidly began to surpass the Mediterranean empires in book production."[7] During the Tang dynasty, China became the world leader in book production. In addition the gradual spread of woodblock printing from the late Tang and Song further boosted their lead ahead of the rest of the world.[21]

From the fourth century CE to about 1500, the biggest library collections in China were three to four times larger than the largest collections in Europe. The imperial government book collections in the Tang numbered about 5,000 to 6,000 titles (89,000 juan) in 721. The Song imperial collections at their height in the early twelfth century may have risen to 4,000 to 5,000 titles. These are indeed impressive numbers, but the imperial libraries were exceptional in China and their use was highly restricted. Only very few libraries in the Tang and Song held more than one or two thousand titles (a size not even matched by the manuscript collections of the grandest of the great cathedral libraries in Europe).[22]

— Endymion Wilkinson

However despite the initial advantage afforded to China by the paper medium, by the 9th century its spread and development in the middle east had closed the gap between the two regions. Between the 9th to early 12th centuries, libraries in Cairo, Baghdad, and Cordoba held collections larger than even the ones in China, and dwarfed those in Europe. From about 1500 the maturation of paper making and printing in Southern Europe also had an effect in closing the gap with the Chinese. The Venetian Domenico Grimani's collection numbered 15,000 volumes by the time of his death in 1523. After 1600, European collections completely overtook those in China. The Bibliotheca Augusta numbered 60,000 volumes in 1649 and surged to 120,000 in 1666. In the 1720s the Bibliotheque du Roi numbered 80,000 books and the Cambridge University 40,000 in 1715. After 1700, libraries in North America also began to overtake those of China, and toward the end of the century, Thomas Jefferson's private collection numbered 4,889 titles in 6,487 volumes. The European advantage only increased further into the 19th century as national collections in Europe and America exceeded a million volumes while a few private collections, such as that of Lord Action, reached 70,000.[22]

European book production began to catch up with China after the introduction of the mechanical printing press in the mid fifteenth century. Reliable figures of the number of imprints of each edition are as hard to find in Europe as they are in China, but one result of the spread of printing in Europe was that public and private libraries were able to build up their collections and for the first time in over a thousand years they began to match and then overtake the largest libraries in China.[21]

— Endymion Wilkinson

Paper became central to the three arts of China – poetry, painting, and calligraphy. In later times paper constituted one of the 'Four Treasures of the Scholar's Studio,' alongside the brush, the ink, and the inkstone.[23]

Paper in Asia

After its origin in central China, the production and use of paper spread steadily. It is clear that paper was used at Dunhuang by AD 150, in Loulan in the modern-day province of Xinjiang by 200, and in Turpan by 399. Paper was concurrently introduced in Japan sometime between the years 280 and 610.[24]

Vietnam

Paper spread to Vietnam in the 3rd century.[16]

Korea

Paper spread to Korea in the 4th century.[16]

Japan

Paper spread to Japan in the 5th century.[16]

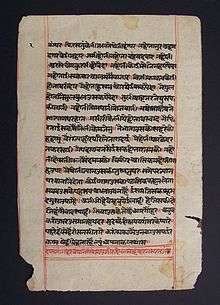

India

Paper spread to India in the 7th century.[16][25] However, the use of paper was not widespread there until the 12th century.[26]

Islamic world

After the defeat of the Chinese in the Battle of Talas in 751 (present day Kyrgyzstan), the invention spread to the Middle East.[27]

The legend goes,[28] the secret of papermaking was obtained from two Chinese prisoners from the Battle of Talas, which led to the first paper mill in the Islamic world being founded in Samarkand in Sogdia (modern-day Uzbekistan). There was a tradition that Muslims would release their prisoners if they could teach ten Muslims any valuable knowledge.[29] There are records of paper being made at Gilgit in Pakistan by the sixth century, in Samarkand by 751, in Baghdad by 793, in Egypt by 900, and in Fes, Morocco around 1100.[30]

The laborious process of paper making was refined and machinery was designed for bulk manufacturing of paper. Production began in Baghdad, where a method was invented to make a thicker sheet of paper, which helped transform papermaking from an art into a major industry.[31] The use of water-powered pulp mills for preparing the pulp material used in papermaking, dates back to Samarkand in the 8th century,[32] though this should not be confused with paper mills (see Paper mills section below). The Muslims also introduced the use of trip hammers (human- or animal-powered) in the production of paper, replacing the traditional Chinese mortar and pestle method. In turn, the trip hammer method was later employed by the Chinese.[33] Historically, trip hammers were often powered by a water wheel, and are known to have been used in China as long ago as 40 BC or maybe even as far back as the Zhou Dynasty (1050 BC–221 BC).[34]

By the 9th century, Muslims were using paper regularly, although for important works like copies of the revered Qur'an, vellum was still preferred.[35] Advances in book production and bookbinding were introduced.[36] In Muslim countries they made books lighter—sewn with silk and bound with leather-covered paste boards; they had a flap that wrapped the book up when not in use. As paper was less reactive to humidity, the heavy boards were not needed. By the 12th century in Marrakech in Morocco a street was named "Kutubiyyin" or book sellers which contained more than 100 bookshops.[37]

In 1035 a Persian traveler visiting markets in Cairo noted that vegetables, spices and hardware were wrapped in paper for the customers after they were sold.[38] Since the First Crusade in 1096, paper manufacturing in Damascus had been interrupted by wars, but its production continued in two other centres. Egypt continued with the thicker paper, while Iran became the center of the thinner papers. Papermaking was diffused across the Islamic world, from where it was diffused further west into Europe.[39] Paper manufacture was introduced to India in the 13th century by Muslim merchants, where it almost wholly replaced traditional writing materials.[35]

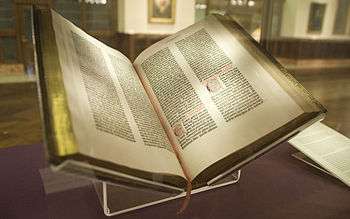

Paper in Europe

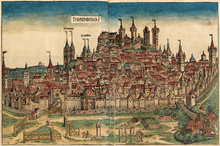

The oldest known paper document in the West is the Mozarab Missal of Silos from the 11th century, probably using paper made in the Islamic part of the Iberian Peninsula. They used hemp and linen rags as a source of fiber. The first recorded paper mill in the Iberian Peninsula was in Xàtiva in 1056.[40][41] Papermaking reached Europe as early as 1085 in Toledo and was firmly established in Xàtiva, Spain by 1150. It is clear that France had a paper mill by 1190, and by 1276 mills were established in Fabriano, Italy and in Treviso and other northern Italian towns by 1340. Papermaking then spread further northwards, with evidence of paper being made in Troyes, France by 1348, in Holland sometime around 1340–1350, in Mainz, Germany in 1320, and in Nuremberg by 1390 in a mill set up by Ulman Stromer.[42] This was just about the time when the woodcut printmaking technique was transferred from fabric to paper in the old master print and popular prints. There was a paper mill in Switzerland by 1432 and the first mill in England was set up by John Tate in 1490 near Stevenage in Hertfordshire,[43] but the first commercially successful paper mill in Britain did not occur before 1588 when John Spilman set up a mill near Dartford in Kent.[44] During this time, paper making spread to Poland by 1491, to Austria by 1498, to Russia by 1576, to the Netherlands by 1586, to Denmark by 1596, and to Sweden by 1612.[30]

Arab prisoners who settled in a town called Borgo Saraceno in the Italian Province of Ferrara introduced Fabriano artisans in the Province of Ancona the technique of making paper by hand. At the time they were renowned for their wool-weaving and manufacture of cloth. Fabriano papermakers considered the process of making paper by hand an art form and were able to refine the process to successfully compete with parchment which was the primary medium for writing at the time. They developed the application of stamping hammers to reduce rags to pulp for making paper, sizing paper by means of animal glue, and creating watermarks in the paper during its forming process. The Fabriano used glue obtained by boiling scrolls or scraps of animal skin to size the paper; it is suggested that this technique was recommended by the local tanneries. The introduction of the first European watermarks in Fabriano was linked to applying metal wires on a cover laid against the mould which was used for forming the paper.[45]

They adapted the waterwheels from the fuller's mills to drive a series of three wooden hammers per trough. The hammers were raised by their heads by cams fixed to a waterwheel's axle made from a large tree trunk.[46][47]

Americas

In the Americas, archaeological evidence indicates that a similar bark-paper writing material was used by the Mayans no later than the 5th century AD.[48] Called amatl or amate, it was in widespread use among Mesoamerican cultures until the Spanish conquest. The earliest sample of amate was found at Huitzilapa near the Magdalena Municipality, Jalisco, Mexico, belonging to the shaft tomb culture. It is dated to 75 BC.[49]

The production of amate is much more similar to paper than papyrus. The bark material is soaked in water, or in modern methods boiled, so that it breaks down into a mass of fibres. They are then laid out in a frame and pressed into sheets. It is a true paper product in that the material is not in its original form, but the base material has much larger fibres than those used in modern papers. As a result, amate has a rougher surface than modern paper, and may dry into a sheet with hills and valleys as the different length fibres shrink.

European papermaking spread to the Americas first in Mexico by 1575 and then in Philadelphia by 1690.[30]

Paper mills

The use of human and animal powered mills was known to Chinese and Muslim papermakers. However, evidence for water-powered paper mills is elusive among both prior to the 11th century.[50][51][52][53] The general absence of the use of water-powered paper mills in Muslim papermaking prior to the 11th century is suggested by the habit of Muslim authors at the time to call a production center not a "mill", but a "paper manufactory".[54]

Donald Hill has identified a possible reference to a water-powered paper mill in Samarkand, in the 11th-century work of the Persian scholar Abu Rayhan Biruni, but concludes that the passage is "too brief to enable us to say with certainty" that it refers to a water-powered paper mill.[55] This is seen by Halevi as evidence of Samarkand first harnessing waterpower in the production of paper, but notes that it is not known if waterpower was applied to papermaking elsewhere across the Islamic world at the time.[56] Burns remains sceptical, given the isolated occurrence of the reference and the prevalence of manual labour in Islamic papermaking elsewhere prior to the 13th century.[57]

Clear evidence of a water-powered paper mill dates to 1282 in the Spanish Kingdom of Aragon.[58] A decree by the Christian king Peter III addresses the establishment of a royal "molendinum", a proper hydraulic mill, in the paper manufacturing centre of Xàtiva.[58] The crown innovation originates from the Muslim Mudéjar community in the Moorish quarter of Xàtiva, where paper mills were a Muslim Mudejar operated enterprise.[59] However, it appears to be resented by sections of the local Muslim papermakering community; the document guarantees them the right to continue the way of traditional papermaking by beating the pulp manually and grants them the right to be exempted from work in the new mill.[58] Paper making centers began to multiply in the late 13th century in Italy, reducing the price of paper to one sixth of parchment and then falling further; paper making centers reached Germany a century later.[60]

The first paper mill north of the Alps was established in Nuremberg by Ulman Stromer in 1390; it is later depicted in the lavishly illustrated Nuremberg Chronicle.[61] From the mid-14th century onwards, European paper milling underwent a rapid improvement of many work processes.[62]

Fiber sources

Before the industrialisation of the paper production the most common fibre source was recycled fibres from used textiles, called rags. The rags were from hemp, linen and cotton.[63] A process for removing printing inks from recycled paper was invented by German jurist Justus Claproth in 1774.[63] Today this method is called deinking. It was not until the introduction of wood pulp in 1843 that paper production was not dependent on recycled materials from ragpickers.[63]

19th-century advances in papermaking

Although cheaper than vellum, paper remained expensive, at least in book-sized quantities, through the centuries, until the advent of steam-driven paper making machines in the 19th century, which could make paper with fibres from wood pulp. Although older machines predated it, the Fourdrinier papermaking machine became the basis for most modern papermaking. Nicholas Louis Robert of Essonnes, France, was granted a patent for a continuous paper making machine in 1799. At the time he was working for Leger Didot with whom he quarrelled over the ownership of the invention. Didot sent his brother-in-law, John Gamble, to meet Sealy and Henry Fourdrinier, stationers of London, who agreed to finance the project. Gamble was granted British patent 2487 on 20 October 1801. With the help particularly of Bryan Donkin, a skilled and ingenious mechanic, an improved version of the Robert original was installed at Frogmore Paper Mill, Hertfordshire, in 1803, followed by another in 1804. A third machine was installed at the Fourdriniers' own mill at Two Waters. The Fourdriniers also bought a mill at St Neots intending to install two machines there and the process and machines continued to develop.

However, experiments with wood showed no real results in the late 18th century and at the start of the 19th century. By 1800, Matthias Koops (in London, England) further investigated the idea of using wood to make paper, and in 1801 he wrote and published a book titled Historical account of the substances which have been used to describe events, and to convey ideas, from the earliest date, to the invention of paper.[64] His book was printed on paper made from wood shavings (and adhered together). No pages were fabricated using the pulping method (from either rags or wood). He received financial support from the royal family to make his printing machines and acquire the materials and infrastructure needed to start his printing business. But his enterprise was short lived. Only a few years following his first and only printed book (the one he wrote and printed), he went bankrupt. The book was very well done (strong and had a fine appearance), but it was very costly.[65][66][67]

Then in the 1830s and 1840s, two men on two different continents took up the challenge, but from a totally new perspective. Both Friedrich Gottlob Keller and Charles Fenerty began experiments with wood but using the same technique used in paper making; instead of pulping rags, they thought about pulping wood. And at about the same time, by mid-1844, they announced their findings. They invented a machine which extracted the fibres from wood (exactly as with rags) and made paper from it. Charles Fenerty also bleached the pulp so that the paper was white. This started a new era for paper making. By the end of the 19th-century almost all printers in the western world were using wood in lieu of rags to make paper.[68]

Together with the invention of the practical fountain pen and the mass-produced pencil of the same period, and in conjunction with the advent of the steam driven rotary printing press, wood based paper caused a major transformation of the 19th century economy and society in industrialized countries. With the introduction of cheaper paper, schoolbooks, fiction, non-fiction, and newspapers became gradually available by 1900. Cheap wood based paper also meant that keeping personal diaries or writing letters became possible and so, by 1850, the clerk, or writer, ceased to be a high-status job.

The original wood-based paper was acidic due to the use of alum and more prone to disintegrate over time, through processes known as slow fires. Documents written on more expensive rag paper were more stable. Mass-market paperback books still use these cheaper mechanical papers (see below), but book publishers can now use acid-free paper for hardback and trade paperback books.

Determining provenance

Determining the provenance of paper is a complex process that can be done in a variety of ways. The easiest way is using a known sheet of paper as an exemplar. Using known sheets can produce an exact identification. Next, comparing watermarks with those contained in catalogs or trade listings can yield useful results. Inspecting the surface can also determine age and location by looking for distinct marks from the production process. Chemical and fiber analysis can be used to establish date of creation and perhaps location.[69]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of paper. |

Notes

- ↑ Confusingly, parchment paper is a treated paper used in baking, and unrelated to true parchment.

References

- ↑ "Papyrus definition". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 38

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 38

- 1 2 3 Barrett 2008, p. 34.

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 2

- 1 2 David Buisseret (1998), Envisaging the City, U Chicago Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-226-07993-6

- 1 2 3 4 Wilkinson 2012, p. 908.

- ↑ Papermaking. (2007). In: Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 9, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ "eNewsletter". World Archeological Congress. August 2006. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- 1 2 Tsien 1985, p. 40 uses Wade-Giles transcription

- 1 2 3 Tsien 1985, p. 122

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 1

- 1 2 3 4 Tsien 1985, p. 123

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 105

- ↑ Barrett 2008, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilkinson 2012, p. 909.

- ↑ Barrett 2008, p. 37.

- ↑ Barret 2008, p. 37-38.

- ↑ Barrett 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Barrett 2008, p. 39.

- 1 2 Wilkinson 2012, p. 935.

- 1 2 Wilkinson 2012, p. 934.

- ↑ Barret 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ DeVinne, Theo. L. The Invention of Printing. New York: Francis Hart & Co., 1876. p. 134

- ↑ Tsien 1985, pp. 2–3

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 3

- ↑ Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998. (pp 58) ISBN 0-471-29198-6

- ↑ Quraishi, Silim "A survey of the development of papermaking in Islamic Countries", Bookbinder, 1989 (3): 29–36.

- ↑ Shirazi, Imam Muhammad. The Prophet Muhammad – A Mercy to the World. Createspace Independent Pub, 2013, p. 74

- 1 2 3 Harrison, Frederick. A Book about Books. London: John Murray, 1943. p. 79. Mandl, George. "Paper Chase: A Millennium in the Production and Use of Paper". Myers, Robin & Michael Harris (eds). A Millennium of the Book: Production, Design & Illustration in Manuscript & Print, 900–1900. Winchester: St. Paul’s Bibliographies, 1994. p. 182. Mann, George. Print: A Manual for Librarians and Students Describing in Detail the History, Methods, and Applications of Printing and Paper Making. London: Grafton & Co., 1952. p. 79. McMurtrie, Douglas C. The Book: The Story of Printing & Bookmaking. London: Oxford University Press, 1943. p. 63.

- ↑ Mahdavi, Farid (2003), "Review: Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World by Jonathan M. Bloom", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, MIT Press, 34 (1): 129–30, doi:10.1162/002219503322645899

- ↑ Lucas, Adam (2006), Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology, Brill Publishers, pp. 65 & 84, ISBN 90-04-14649-0

- ↑ Dard Hunter (1978), Papermaking: the history and technique of an ancient craft, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-23619-6

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2. p. 184.

- 1 2 Fischer, Steven R. (2004), A History of Writing, London: Reaktion Books, p. 264, ISBN 1-86189-101-6

- ↑ Al-Hassani, Woodcock and Saoud, "1001 Inventions, Muslim heritage in Our World", FSTC Publishing, 2006, reprinted 2007, pp. 218-219.

- ↑ The famous Kutubiya mosque is named so because of its location in this street

- ↑ Diana Twede (2005), "The Origins of Paper Based Packaging" (PDF), Conference on Historical Analysis & Research in Marketing Proceedings, 12: 288–300 [289], archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011, retrieved 2010-03-20

- ↑ Mahdavi, Farid (2003), "Review: Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World by Jonathan M. Bloom", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, MIT Press, 34 (1): 129–30, doi:10.1162/002219503322645899

- ↑ Richard Leslie Hills: Papermaking in Britain 1488–1988: A Short History. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015, ISBN 978-1-4742-4127-4 (Reprint), S. 2.

- ↑ Filipe Duarte Santos: Humans on Earth: From Origins to Possible Futures. Springer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-05359-7, S. 116.

- ↑ Fuller, Neathery Batsell (2002). "A Brief history of paper". Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ Historie ručního papíru

- ↑ "Dartford, cradle of Britain's papermaking industry". Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ Hills, Richard (1936). "Early Italian papermaking : a crucial technical revolution": 37–46.

- ↑ Papiernicze, Rękodzieło; Dąbrowski, Józef (1991). "The Papermaking Craft": 152.

- ↑ Dabrowski, Jozef (July 2008). "Paper Manufacture in Central and Eastern Europe Before the Introduction of Paper-making Machines" (PDF): 6.

- ↑ The Construction of the Codex In Classic- and post classic-Period Maya Civilization Maya Codex and Paper Making

- ↑ Benz, Bruce; Lorenza Lopez Mestas; Jorge Ramos de la Vega (2006). "Organic Offerings, Paper, and Fibers from the Huitzilapa Shaft Tomb, Jalisco, Mexico". Ancient Mesoamerica. 17 (2). pp. 283–296.

- ↑ Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin 1985, pp. 68–73

- ↑ Lucas 2005, p. 28, fn. 70

- ↑ Burns 1996, pp. 414f.:

It has also become universal to talk of paper "mills" (even of 400 such mills at Fez!), relating these to the hydraulic wonders of Islamic society in east and west. All our evidence points to non-hydraulic hand production, however, at springs away from rivers which it could pollute.

- ↑ Thompson 1978, p. 169:

European papermaking differed from its precursors in the mechanization of the process and in the application of water power. Jean Gimpel, in The Medieval Machine (the English translation of La Revolution Industrielle du Moyen Age), points out that the Chinese and Muslims used only human and animal force. Gimpel goes on to say : "This is convincing evidence of how technologically minded the Europeans of that era were. Paper had traveled nearly halfway around the world, but no culture or civilization on its route had tried to mechanize its manufacture."'

- ↑ Burns 1996, pp. 414f.:

Indeed, Muslim authors in general call any "paper manufactory" a wiraqah – not a "mill" (tahun)

- ↑ Donald Routledge Hill (1996), A history of engineering in classical and medieval times, Routledge, pp. 169–71, ISBN 0-415-15291-7

- ↑ Leor Halevi (2008), "Christian Impurity versus Economic Necessity: A Fifteenth-Century Fatwa on European Paper", Speculum, Cambridge University Press, 83: 917–945 [917–8], doi:10.1017/S0038713400017073

- ↑ Burns 1996, pp. 414−417

- 1 2 3 Burns 1996, pp. 417f.

- ↑ Thomas F. Glick (2014). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 385.

- ↑ Burns 1996, p. 417

- ↑ Stromer 1960

- ↑ Stromer 1993, p. 1

- 1 2 3 Göttsching, Lothar; Pakarinen, Heikki (2000), "1", Recycled Fiber and Deinking, Papermaking Science and Technology, 7, Finland: Fapet Oy, pp. 12–14, ISBN 952-5216-07-1

- ↑ Koops, Matthias. Historical account of the substances which have been used to describe events, and to convey ideas, from the earliest date, to the invention of paper. London: Printed by T. Burton, 1800.

- ↑ Carruthers, George. Paper in the Making. Toronto: The Garden City Press Co-Operative, 1947.

- ↑ Matthew, H.C.G. and Brian Harrison. "Koops. Matthias." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: from the earliest times to the year 2000, Vol. 32. London: Oxford University Press, 2004: 80.

- ↑ Burger, Peter. Charles Fenerty and his Paper Invention. Toronto: Peter Burger, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9783318-1-8 pp.30–32

- ↑ Burger, Peter. Charles Fenerty and his Paper Invention. Toronto: Peter Burger, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9783318-1-8

- ↑ Suarez, S.J., Michael F.; Woudhuysen, H.R. (2013). The Book: A Global History. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199679416.

Sources

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Bloom, Jonathan (2001). Paper before print: the history and impact of paper in the Islamic world. Yale University Press.

- Burns, Robert I. (1996), "Paper comes to the West, 800–1400", in Lindgren, Uta, Europäische Technik im Mittelalter. 800 bis 1400. Tradition und Innovation (4th ed.), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 413–422, ISBN 3-7861-1748-9

- Febvre, Lucien; Martin, Henri-Jean (1997), The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450–1800, London: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-108-2

- Lucas, Adam Robert (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture, 46 (1): 1–30, doi:10.1353/tech.2005.0026

- Stromer, Wolfgang von (1960), "Das Handelshaus der Stromer von Nürnberg und die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Papiermühle", Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 47: 81–104

- Stromer, Wolfgang von (1993), "Große Innovationen der Papierfabrikation in Spätmittelalter und Frühneuzeit", Technikgeschichte, 60 (1): 1–6

- Thompson, Susan (1978), "Paper Manufacturing and Early Books", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 314: 167–176, Bibcode:1978NYASA.314..167T, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb47791.x

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985), Paper and Printing, Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Vol. 5 part 1, Cambridge University Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute