Kiln

A kiln (/kɪln/ or /kɪl/,[1] originally pronounced "kill", with the "n" silent) is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay into pottery, tiles and bricks. Various industries use rotary kilns for pyroprocessing—to calcinate ores, to calcinate limestone to lime for cement, and to transform many other materials.

Etymology and pronunciation

The word kiln descends from the Old English cylene (/ˈkylene/, which was adapted from the Latin culīna 'kitchen, cooking-stove, burning-place. During the Middle English Period, the "n" was not pronounced, as evidenced by kiln having frequently been spelled without the "n",[2] Another word, "miln", a place where wheat is ground, also had a silent "n". Whereas the spelling of "miln" was changed to "mill" to match its pronunciation, "kiln" maintained its spelling, which most likely led to a common mispronunciation, which has now become commonly used. However, there are small bastions where the original pronunciation has endured. Kiln, Mississippi, a small town known for its wood drying kilns that once served the timber industry, is still referred to as "the Kill" by locals.[3]

Unwittingly adding the "n" sound at the end of "kiln" is due to people being introduced to the word through the written language before ever hearing the actual pronunciation. Linguists call this phenomenon "reading pronunciation" where an incorrect pronunciation is read aloud, becomes widespread, eventually reported by dictionaries, and the "original pronunciation, passed from parent to child, mouth to ear, for many generations is lost."[4]

Phonetically, the "ln" in "kiln" is categorized as a digraph: a combination of two letters that make only one sound, such as the "mn" in "hymn". From English Words as Spoken and Written for Upper Grades by James A. Bowen 1900: "The digraph ln, n silent, occurs in kiln. A fall down the kiln can kill you."[5] Bowen was pointing out the humorous fact that "kill" and "kiln" are homophones.[6]

Uses of kilns

Pit fired pottery was produced for thousands of years before the earliest known kiln, which dates to around 6000 BC, and was found at the Yarim Tepe site in modern Iraq.[7] Neolithic kilns were able to produce temperatures greater than 900 °C (1652 °F).[8] Uses include:

- Annealing, fusing and deforming glass, or fusing metallic oxide paints to the surface of glass

- Heat treatment for metallic workpieces

- Ceramics

- Brickworks

- Melting metal for casting

- Smelting ore to extract metal

- Pyrolysis of chemical materials

- Heating limestone with clay in the manufacture of Portland cement, the Cement kiln

- Heating limestone to make quicklime or calcium oxide, the Lime kiln

- Heating gypsum to make plaster of Paris

- For cremation (at high temperature)

- Drying of tobacco leaves

- Drying malted barley for brewing and other fermentations

- Drying hops for brewing (known as a hop kiln or oast house)

- Drying corn (grain) before grinding or storage, sometimes called a corn kiln, corn drying kiln.[9]

- Drying green lumber so it can be used immediately

- Drying wood for use as firewood

- Heating wood to the point of pyrolysis to produce charcoal

Ceramic kilns

Kilns are an essential part of the manufacture of all ceramics. Ceramics require high temperatures so chemical and physical reactions will occur to permanently alter the unfired body. In the case of pottery, clay materials are shaped, dried and then fired in a kiln. The final characteristics are determined by the composition and preparation of the clay body and the temperature at which it is fired. After a first firing, glazes may be used and the ware is fired a second time to fuse the glaze into the body. A third firing at a lower temperature may be required to fix overglaze decoration. Modern kilns often have sophisticated electrical control systems to firing regime, although pyrometric devices are often also used.

Clay consists of fine-grained particles, that are relatively weak and porous. Clay is combined with other minerals to create a workable clay body. Part of the firing process includes sintering. This heats the clay until the particles partially melt and flow together, creating a strong, single mass, composed of a glassy phase interspersed with pores and crystalline material. Through firing, the pores are reduced in size, causing the material to shrink slightly. This crystalline material predominantly consists of silicon and aluminium oxides.

In the broadest terms, there are two types of kiln: intermittent and continuous, both sharing the same basic characteristics of being an insulated box with a controlled inner temperature and atmosphere.

A continuous kiln, sometimes called a tunnel kiln, is a long structure in which only the central portion is directly heated. From the cool entrance, ware is slowly transported through the kiln, and its temperature is increased steadily as it approaches the central, hottest part of the kiln. From there, it continues through the kiln, and the surrounding temperature is reduced until it exits the kiln nearly at room temperature. A continuous kiln is energy-efficient, because heat given off during cooling is recycled to pre-heat the incoming ware. In some designs, the ware is left in one place, while the heating zone moves across it. Kilns in this type include:

- Hoffmann kiln

- Bull’s Trench kiln

- Habla (Zig-Zag) kiln

- Roller kiln: A special type of kiln, common in tableware and tile manufacture, is the roller-hearth kiln, in which wares placed on bats are carried through the kiln on rollers.

In the intermittent kiln. the ware to be fired is placed into the kiln. The kiln is closed, and the internal temperature increased according to a schedule. After the firing is completed, both the kiln and the ware are cooled. The ware is removed, the kiln is cleaned and the next cycle begins. Kilns in this type include:[10]

- Clamp kiln

- Skove kiln

- Scotch kiln

- Down-Draft kiln

- Shuttle Kilns: this is a car-bottom kiln with a door on one or both ends. Burners are positioned top and bottom on each side, creating a turbulent circular air flow. This type of kiln is generally a multi-car design and is used for processing whitewares, technical ceramics and refractories in batches. Depending upon size and mass of ware, shuttle kilns may be equipped with car moving devices to transfer fired and unfired ware in and out of the kiln. Shuttle kilns can be either updraft or downdraft in design. A Shuttle Kiln derives its name from the fact that kiln cars can enter a shuttle kiln from either end of the kiln for processing, whereas a tunnel kiln has flow in only one direction.

Kiln technology is very old. The development of the kiln from a simple earthen trench filled with pots and fuel, pit firing, to modern methods happened in stages. One improvement was to build a firing chamber around pots with baffles and a stoking hole. This conserved heat. A chimney stack improves the air flow or draw of the kiln, thus burning the fuel more completely.

Chinese kiln technology has always been a key factor in the development of Chinese pottery, and until recent centuries was far ahead of other parts of the world. The Chinese developed effective kilns capable of firing at around 1,000°C before 2000 BC. These were updraft kilns, often built below ground. Two main types of kiln were developed by about 200 AD and remained in use until modern times. These are the dragon kiln of hilly southern China, usually fuelled by wood, long and thin and running up a slope, and the horseshoe-shaped mantou kiln of the north Chinese plains, smaller and more compact. Both could reliably produce the temperatures of up to 1300°C or more needed for porcelain. In the late Ming, the egg-shaped kiln or zhenyao was developed at Jingdezhen, but mainly used there. This was something of a compromise between the other types, and offered locations in the firing chamber with a range of firing conditions.[11]

Both Ancient Roman pottery and medieval Chinese pottery could be fired in industrial quantities, with tens of thousands of pieces in a single firing.[12] Early examples of simpler kilns found in Britain include those that made roof-tiles during the Roman occupation. These kilns were built up the side of a slope, such that a fire could be lit at the bottom and the heat would rise up into the kiln.

Traditional kilns include:

- Dragon kiln of south China: thin and long, climbing up a hillside. This type spread to the rest of East Asia giving the Japanese Anagama kiln, arriving via Korea in the 5th century. This kiln usually consists of one long firing chamber, pierced with smaller ware stacking ports on one side, with a firebox at one end and a flue at the other. Firing time can vary from one day to several weeks. Traditional anagama kilns are also built on a slope to allow for a better draft. The Japanese Noborigama kiln is an evolution from Anagama design as a multi-chamber kiln where wood is stacked from the front firebox at first, then only through the side-stoking holes with the benefit of having air heated up to 600 °C (1,112 °F) from the front firebox, enabling more efficient firings.

- Khmer Kiln: quite similar to the Anagama kiln; however, traditional Khmer Kilns had a flat roof. Chinese, Korean or Japanese kilns have an arch roof. These types of kiln vary in size and can measure in the tens of meters. The firing time also varies and can last several days.

- Bottle kiln: a type of intermittent kiln, usually coal-fired, formerly used in the firing of pottery; such a kiln was surrounded by a tall brick hovel or cone, of typical bottle shape. The tableware was enclosed in sealed fireclay saggars, as the heat and smoke from the fires passed through the oven it would be fired at temperatures up to 1,400 °C (2,552 °F).

- Biscuit kiln: The first firing would take place in the biscuit kiln

- Glost kiln: The biscuit-ware was glazed and given a second glost firing in the larger glost kilns

- Mantou kiln of north China, smaller and more compact than the dragon kiln.

- Muffle Kiln: This was used to fire over-glaze decoration, at a temperature under 800 °C (1,472 °F). in these cool kilns the smoke from the fires passed through flues outside the oven.

- Catenary arch kiln: Typically used for the firing of pottery using salt, these by their form (a catenary arch) tend to retain their shape over repeated heating and cooling cycles, whereas other types require extensive metalwork supports.

- Sèvres kiln: invented in Sèvres, France, it efficiently generated high-temperatures 1,240 °C (2,264 °F) to produce waterproof ceramic bodies and easy-to-obtain glazes. It features a down-draft design that produces high temperature in shorter time, even with wood-firing.

- Bourry box kiln, similar to previous one.

Modern kilns

With the industrial age, kilns were designed to use electricity and more refined fuels, including natural gas and propane. Many large industrial pottery kilns use natural gas, as it is generally clean, efficient and easy to control. Modern kilns can be fitted with computerized controls allowing for fine adjustments during the firing. A user may choose to control the rate of temperature climb or ramp, hold or soak the temperature at any given point, or control the rate of cooling. Both electric and gas kilns are common for smaller scale production in industry and craft, handmade and sculptural work.

The temperature of some kilns is controlled by pyrometric cones—devices that begin to melt at specific temperatures.

Modern kilns include:

- Retort kiln: a type of kiln which can reach temperatures around 1,500 °C (2,732 °F) for extended periods of time. Typically, these kilns are used in industrial purposes, and feature movable charging cars which make up the bottom and door of the kiln.

- Electric kilns: kilns operated by electricity were developed in the 20th century, primarily for smaller scale use such as in schools, universities, and hobby centers. The atmosphere in most designs of electric kiln is rich in oxygen, as there is no open flame to consume oxygen molecules. However, reducing conditions can be created with appropriate gas input, or by using saggars in a particular way.

- Feller kiln: brought contemporary design to wood firing by re-using unburnt gas from the chimney to heat intake air before it enters the firebox. This leads to an even shorter firing cycle and less wood consumption. This design requires external ventilation to prevent the in-chimney radiator from melting, being typically in metal. The result is a very efficient wood kiln firing one cubic metre of ceramics with one cubic meter of wood.

- Microwave assisted firing: this technique combine microwave energy with more conventional energy sources, such as radiant gas or electric heating, to process ceramic materials to the required high temperatures. Microwave-assisted firing offers significant economic benefits.

- Top-hat kiln: an intermittent kiln of a type sometimes used to fire pottery. The ware is set on a refractory hearth, or plinth, over which a box-shaped cover is lowered.

Wood-drying kiln

Green wood coming straight from the felled tree has far too high a moisture content to be commercially useful and will rot, warp and split. Both hardwoods and softwood must be left to dry out until the moisture content is between 18% and 8%. This can be a long process, or it is speeded up by use of a kiln. A variety of kiln technologies exist today: conventional, dehumidification, solar, vacuum and radio frequency.

- Conventional wood dry

- [13] are either package-type (side-loader) or track-type (tram) construction. Most hardwood lumber kilns are side-loader kilns in which fork trucks are used to load lumber packages into the kiln. Most softwood kilns are track types in which the timber (US. lumber) is loaded on kiln/track cars for loading the kiln. Modern high-temperature, high-air-velocity conventional kilns can typically dry 1-inch-thick (25 mm) green wood in 10 hours down to a moisture content of 18%. However, 1-inch-thick green Red Oak requires about 28 days to dry down to a moisture content of 8%.

- Heat is typically introduced via steam running through fin/tube heat exchangers controlled by on/off pneumatic valves. Humidity is removed by a system of vents, the specific layout of which are usually particular to a given manufacturer. In general, cool dry air is introduced at one end of the kiln while warm moist air is expelled at the other. Hardwood conventional kilns also require the introduction of humidity via either steam spray or cold water misting systems to keep the relative humidity inside the kiln from dropping too low during the drying cycle. Fan directions are typically reversed periodically to ensure even drying of larger kiln charges.

- Most softwood kilns operate below 115 °C (239 °F) temperature. Hardwood kiln drying schedules typically keep the dry bulb temperature below 80 °C (176 °F). Difficult-to-dry species might not exceed. 60 °C (140 °F)

- Dehumidification kilns

- are similar to other kilns in basic construction and drying times are usually comparable. Heat comes primarily from an integral dehumidification unit that also removes humidity. Auxiliary heat is often provided early in the schedule to supplement the dehumidifier.

- Solar kilns

- are conventional kilns, typically built by hobbyists to keep initial investment costs low. Heat is provided via solar radiation, while internal air circulation is typically passive.

- Vacuum and radio frequency kilns

- reduce the air pressure to attempt to speed up the drying process. A variety of these vacuum technologies exist, varying primarily in the method heat is introduced into the wood charge. Hot water platten vacuum kilns use aluminum heating plates with the water circulating within as the heat source, and typically operate at significantly reduced absolute pressure. Discontinuous and SSV (super-heated steam) use atmosphere pressure to introduce heat into the kiln charge. The entire kiln charge comes up to full atmospheric pressure, the air in the chamber is then heated and finally a vacuum is pulled as the charge cools. SSV run at partial-atmospheres, typically around 1/3 of full atmospheric pressure, in a hybrid of vacuum and conventional kiln technology (SSV kilns are significantly more popular in Europe where the locally harvested wood is easier to dry than the North American woods. RF/V (radio frequency + vacuum) kilns use microwave radiation to heat the kiln charge, and typically have the highest operating cost due to the heat of vaporization being provided by electricity rather than local fossil fuel or waste wood sources.

The economics of different wood drying technologies are based on the total energy, capital, insurance/risk, environmental impacts, labor, maintenance, and product degradation costs. These costs which can be a significant part of plant costs, involve the differential impact of the presence of drying equipment in a specific plant. Every piece of equipment from the green trimmer to the infeed system at the planer mill is part the "drying system". The true costs of the drying system can only be determined when comparing the total plant costs and risks with and without drying.

Kiln dried firewood was pioneered during the 1980s, this was later adopted extensively in Europe due to the economic and practical benefits of selling wood with a lower moisture content.[14] [15][16]

The total (harmful) air emissions produced by wood kilns, including their heat source, can be significant. Typically, the higher the temperature the kiln operates at, the larger amount of emissions are produced (per pound of water removed). This is especially true in the drying of thin veneers and high-temperature drying of softwoods.

Gallery

Brickmaking kilns, Mekong delta. The cargo boat in the foreground is carrying the rice chaff used as fuel for the firing.

Brickmaking kilns, Mekong delta. The cargo boat in the foreground is carrying the rice chaff used as fuel for the firing. A wood fired pottery kiln in Hoi An Vietnam.

A wood fired pottery kiln in Hoi An Vietnam. A Catenary Arch kiln used for firing high temperature electron tube grade aluminium oxide ceramics

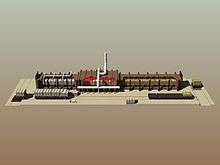

A Catenary Arch kiln used for firing high temperature electron tube grade aluminium oxide ceramics A two-story porcelain kiln with furnaces á alandier in Sèvres, France circa 1880

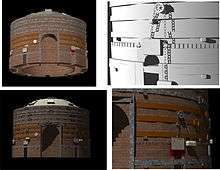

A two-story porcelain kiln with furnaces á alandier in Sèvres, France circa 1880 CAD representation of a Beehive Kiln

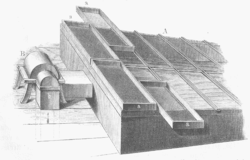

CAD representation of a Beehive Kiln CAD representation of a Tunnel kiln

CAD representation of a Tunnel kiln

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Kiln". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ↑ "kiln". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Ellis, Dan (2000). Kiln Kountry - Home of Brett Favre. ISBN 9780967946412.

- ↑ Dick Margulis (8 April 2007). "Jumpin' up and down yelling "KILN! KILN!"". words/myth/amper & virgule. Dick Margulis. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ↑ Bowen, James A (1915). "English Words as Spoken and Written, for Upper Grades: Designed to Teach the Powers of Letters and the Construction and Use of Syllables".

- ↑ Alfred Aloisi. "kill, kiln". Homophone.com. Alfred Aloisi. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ↑ Piotr Bienkowski; Alan Millard (15 April 2010). Dictionary of the Ancient Near East. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8122-2115-2.

- ↑ James E. McClellan III; Harold Dorn. Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. JHU Press; 14 April 2006. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6. p. 21.

- ↑ Conran, Sheelagh; et al. (2011). Past Times, Changing Fortunes. Proceedings of a public seminar on archaeological discoveries on national road schemes. ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY, Monograph Series No.8. Dublin: Transport Infrastructure Ireland. pp. 73–84. ISBN 9780956418050.

- ↑ "Small Scale Brickmaking".

- ↑ Rawson, 364, 369-370; Vainker, 222-223; JP Hayes article from the Grove Dictionary of Art

- ↑ Vainker, 222-223; JP Hayes article from the Grove Dictionary of Art

- ↑ Rasmussen 1988.

- ↑ Maviglio, S. 1986. From stump to stove in three days. Yankee. 50(12): 95-96(December).

- ↑ http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fplrn/fplrn254.pdf

- ↑ "Important information and facts about our firewood". www.certainlywood.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-10-27.

References

- Hamer, Frank and Janet. The Potter's Dictionary of Materials and Techniques. A & C Black Publishers, Limited, London, England, Third Edition 1991. ISBN 0-8122-3112-0.

- Smith, Ed. Dry Kiln Design Manual. J.E. Smith Engineering and Consulting, Blooming Grove, Texas. Available for purchase from author J.E. Smith

- M. Kornmann and CTTB, "Clay bricks and roof tiles, manufacturing and properties", Soc. industrie minérale, Paris,(2007) ISBN 2-9517765-6-X

- Rasmussen, E.F. (1988). Forest Products Laboratory, U.S. Department of Agriculture., ed. Dry Kiln Operators Manual. Hardwood Research Council.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kilns. |

| Look up kiln in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |