Embroidery

Embroidery is the craft of decorating fabric or other materials using a needle to apply thread or yarn.

Embroidery may also incorporate other materials such as pearls, beads, quills, and sequins. In modern days, embroidery is usually seen on caps, hats, coats, blankets, dress shirts, denim, dresses, stockings, and golf shirts. Embroidery is available with a wide variety of thread or yarn color.

Some of the basic techniques or stitches of the earliest embroidery are chain stitch, buttonhole or blanket stitch, running stitch, satin stitch, cross stitch. Those stitches remain the fundamental techniques of hand embroidery today.

History

Origins

The process used to tailor, patch, mend and reinforce cloth fostered the development of sewing techniques, and the decorative possibilities of sewing led to the art of embroidery.[1] Indeed, the remarkable stability of basic embroidery stitches has been noted:

It is a striking fact that in the development of embroidery ... there are no changes of materials or techniques which can be felt or interpreted as advances from a primitive to a later, more refined stage. On the other hand, we often find in early works a technical accomplishment and high standard of craftsmanship rarely attained in later times.[2]

The art of embroidery has been found worldwide and several early examples have been found. Works in China have been dated to the Warring States period (5th–3rd century BC).[3] In a garment from Migration period Sweden, roughly 300–700 AD, the edges of bands of trimming are reinforced with running stitch, back stitch, stem stitch, tailor's buttonhole stitch, and whip-stitching, but it is uncertain whether this work simply reinforced the seams or should be interpreted as decorative embroidery.[4]

Ancient Greek mythology has credited the goddess Athena with passing down the art of embroidery along with weaving, leading to the famed competition between herself and the mortal Arachne.[5]

Historical applications and techniques

Depending on time, location and materials available, embroidery could be the domain of a few experts or a widespread, popular technique. This flexibility led to a variety of works, from the royal to the mundane.

Elaborately embroidered clothing, religious objects, and household items often were seen as a mark of wealth and status, as in the case of Opus Anglicanum, a technique used by professional workshops and guilds in medieval England.[6] In 18th-century England and its colonies, samplers employing fine silks were produced by the daughters of wealthy families. Embroidery was a skill marking a girl's path into womanhood as well as conveying rank and social standing.[7]

Conversely, embroidery is also a folk art, using materials that were accessible to nonprofessionals. Examples include Hardanger from Norway, Merezhka from Ukraine, Mountmellick embroidery from Ireland, Nakshi kantha from Bangladesh and West Bengal, and Brazilian embroidery. Many techniques had a practical use such as Sashiko from Japan, which was used as a way to reinforce clothing.[8][9]

The Islamic world

Embroidery was an important art in the Medieval Islamic world. The 17th-century Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi called it the "craft of the two hands". Because embroidery was a sign of high social status in Muslim societies, it became widely popular. In cities such as Damascus, Cairo and Istanbul, embroidery was visible on handkerchiefs, uniforms, flags, calligraphy, shoes, robes, tunics, horse trappings, slippers, sheaths, pouches, covers, and even on leather belts. Craftsmen embroidered items with gold and silver thread. Embroidery cottage industries, some employing over 800 people, grew to supply these items.[10]

In the 16th century, in the reign of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, his chronicler Abu al-Fazl ibn Mubarak wrote in the famous Ain-i-Akbari: "His majesty (Akbar) pays much attention to various stuffs; hence Irani, Ottoman, and Mongolian articles of wear are in much abundance especially textiles embroidered in the patterns of Nakshi, Saadi, Chikhan, Ari, Zardozi, Wastli, Gota and Kohra. The imperial workshops in the towns of Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur and Ahmedabad turn out many masterpieces of workmanship in fabrics, and the figures and patterns, knots and variety of fashions which now prevail astonish even the most experienced travelers. Taste for fine material has since become general, and the drapery of embroidered fabrics used at feasts surpasses every description."[11]

Automation

The development of machine embroidery and its mass production came about in stages in the Industrial Revolution. The earliest machine embroidery used a combination of machine looms and teams of women embroidering the textiles by hand. This was done in France by the mid-1800s.[12] The manufacture of machine-made embroideries in St. Gallen in eastern Switzerland flourished in the latter half of the 19th century.[13]

Classification

Embroidery can be classified according to what degree the design takes into account the nature of the base material and by the relationship of stitch placement to the fabric. The main categories are free or surface embroidery, counted embroidery, and needlepoint or canvas work.[14]

In free or surface embroidery, designs are applied without regard to the weave of the underlying fabric. Examples include crewel and traditional Chinese and Japanese embroidery.

Counted-thread embroidery patterns are created by making stitches over a predetermined number of threads in the foundation fabric. Counted-thread embroidery is more easily worked on an even-weave foundation fabric such as embroidery canvas, aida cloth, or specially woven cotton and linen fabrics . Examples include cross-stitch and some forms of blackwork embroidery.

While similar to counted thread in regards to technique, in canvas work or needlepoint, threads are stitched through a fabric mesh to create a dense pattern that completely covers the foundation fabric.[15] Examples of canvas work include bargello and Berlin wool work.

Embroidery can also be classified by the similarity of appearance. In drawn thread work and cutwork, the foundation fabric is deformed or cut away to create holes that are then embellished with embroidery, often with thread in the same color as the foundation fabric. When created with white thread on white linen or cotton, this work is collectively referred to as whitework.[16] However, whitework can either be counted or free. Hardanger embroidery is a counted embroidery and the designs are often geometric.[17] Conversely, styles such as Broderie anglaise are similar to free embroidery, with floral or abstract designs that are not dependent on the weave of the fabric.[18]

Materials

The fabrics and yarns used in traditional embroidery vary from place to place. Wool, linen, and silk have been in use for thousands of years for both fabric and yarn. Today, embroidery thread is manufactured in cotton, rayon, and novelty yarns as well as in traditional wool, linen, and silk. Ribbon embroidery uses narrow ribbon in silk or silk/organza blend ribbon, most commonly to create floral motifs.[19]

Surface embroidery techniques such as chain stitch and couching or laid-work are the most economical of expensive yarns; couching is generally used for goldwork. Canvas work techniques, in which large amounts of yarn are buried on the back of the work, use more materials but provide a sturdier and more substantial finished textile.[20]

In both canvas work and surface embroidery an embroidery hoop or frame can be used to stretch the material and ensure even stitching tension that prevents pattern distortion. Modern canvas work tends to follow symmetrical counted stitching patterns with designs emerging from the repetition of one or just a few similar stitches in a variety of hues. In contrast, many forms of surface embroidery make use of a wide range of stitching patterns in a single piece of work.[21]

Machine

Contemporary embroidery is stitched with a computerized embroidery machine using patterns digitized with embroidery software. In machine embroidery, different types of "fills" add texture and design to the finished work. Machine embroidery is used to add logos and monograms to business shirts or jackets, gifts, and team apparel as well as to decorate household linens, draperies, and decorator fabrics that mimic the elaborate hand embroidery of the past.

There has also been a development in free hand machine embroidery, new machines have been designed that allow for the user to create free-motion embroidery which has its place in textile arts, quilting, dressmaking, home furnishings and more.[22] Users can use the embroidery software to digitize the digital embroidery designs. These digitized design are then transferred to the embroidery machine with the help of a flash drive and then the embroidery machine embroiders the selected design onto the fabric.

Qualifications

City and Guilds qualification[23] in Embroidery allows embroiderers to become recognized for their skill. This qualification also gives them the credibility to teach. For example, the notable textiles artist, Kathleen Laurel Sage,[24] began her teaching career by getting the City and Guilds Embroidery 1 and 2 qualifications. She has now gone on to write a book on the subject.[25]

Gallery

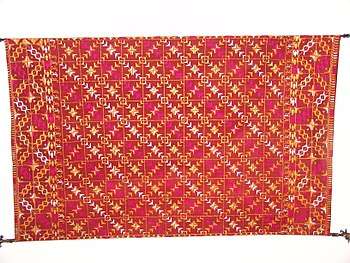

Sindhi embroidery GAJJ, Gajj is a type of ladies shirt embroidered with hand stitched.

Sindhi embroidery GAJJ, Gajj is a type of ladies shirt embroidered with hand stitched. Sindhi embroidery GAJJ 2

Sindhi embroidery GAJJ 2- Detail of embroidered silk gauze ritual garment. Rows of even, round chain stitch used for outline and color. 4th century BC, Zhou tomb at Mashan, Hubei, China.

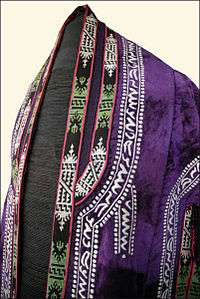

English cope, late 15th or early 16th century. Silk velvet embroidered with silk and gold threads, closely laid and couched. Contemporary Art Institute of Chicago textile collection.

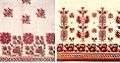

English cope, late 15th or early 16th century. Silk velvet embroidered with silk and gold threads, closely laid and couched. Contemporary Art Institute of Chicago textile collection. Extremely fine underlay of St. Gallen Embroidery

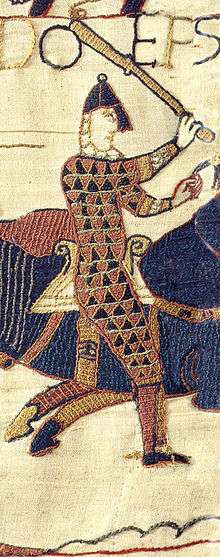

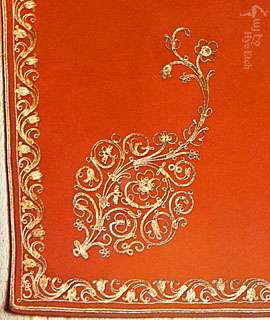

Extremely fine underlay of St. Gallen Embroidery Traditional Turkish embroidery. Izmir Ethnography Museum, Turkey.

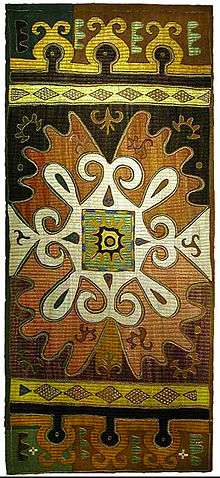

Traditional Turkish embroidery. Izmir Ethnography Museum, Turkey. Traditional Croatian embroidery.

Traditional Croatian embroidery. Brightly coloured Korean embroidery.

Brightly coloured Korean embroidery. Uzbekistan embroidery on a traditional women's parandja robe.

Uzbekistan embroidery on a traditional women's parandja robe. Traditional Peruvian embroidered floral motifs.

Traditional Peruvian embroidered floral motifs. Woman wearing a traditional embroidered Kalash headdress, Pakistan.

Woman wearing a traditional embroidered Kalash headdress, Pakistan. Decorative embroidery on a tefillin bag in Jerusalem, Israel.

Decorative embroidery on a tefillin bag in Jerusalem, Israel. Bookmark of black fabric with multicolored Bedouin embroidery and tassel of embroidery floss

Bookmark of black fabric with multicolored Bedouin embroidery and tassel of embroidery floss.jpg) Chain-stitch embroidery from England circa 1775

Chain-stitch embroidery from England circa 1775 Traditional Bulgarian Floral embrodery from Sofia and Trun.

Traditional Bulgarian Floral embrodery from Sofia and Trun.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gillow and Bryan 1999, p. 12

- ↑ Marie Schuette and Sigrid Muller-Christensen, The Art of Embroidery translated by Donald King, Thames and Hudson, 1964, quoted in Netherton and Owen-Crocker 2005, p. 2

- ↑ Gillow and Bryan 1999, p. 178

- ↑ Coatsworth, Elizabeth: "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery", in Netherton and Owen-Crocker 2005, p. 2

- ↑ Synge, Lanto (2001). Art of Embroidery: History of Style and Technique. Woodbridge, England: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 32. ISBN 9781851493593.

- ↑ Levey and King 1993, p. 12

- ↑ Power, Lisa (27 March 2015). "NGV embroidery exhibition: imagine a 12-year-old spending two years on this..." The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "Handa City Sashiko Program at the Society for Contemporary Craft". Japan-America Society of Pennsylvania. 7 Oct 2016. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ "Sashiko | Seamwork Magazine". www.seamwork.com. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

- ↑ "Saudi Aramco World :The Skill of the Two Hands".

- ↑ "Saudi Aramco World :Mughal Maal".

- ↑ Knight, Charles (1858). Pictorial Gallery of Arts. England.

- ↑ Röllin, Peter. Stickerei-Zeit, Kultur und Kunst in St. Gallen 1870–1930. VGS Verlagsgemeinschaft, St. Gallen 1989, ISBN 3-7291-1052-7 (in German)

- ↑ Corbet, Mary (October 3, 2016). "Needlework Terminology: Surface Embroidery". Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ↑ Gillow and Bryan 1999, p. 198

- ↑ Readers Digest 1979, pp. 74–91

- ↑ Yvette Stanton. Early Style Hardanger. Vetty Creations. ISBN 978-0-9757677-7-1.

- ↑ Catherine Amoroso Leslie (1 January 2007). Needlework Through History: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 34, 226, 58. ISBN 978-0-313-33548-8. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ van Niekerk 2006

- ↑ Readers Digest 1979, pp. 112–115

- ↑ Readers Digest 1979, pp. 1–19, 112–117

- ↑ "Using logo embroidery". Oekaki Renaissance. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ "Creative".

- ↑ "A Little About Me". Kathleen Laurel Sage.

- ↑ The Zen Cart® Team; et al. "Embroidered Soldered and Heat Zapped Surfaces by Kathleen Laurel Sage".

References

- Berman, Pat (2000). "Berlin Work". American Needlepoint Guild. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- Caulfeild, S.F.A.; B.C. Saward (1885). The Dictionary of Needlework.

- Crummy, Andrew (2010). The Prestonpans Tapestry 1745. Burke's Peerage & Gentry, for Battle of Prestonpans (1745) Heritage Trust.

- Embroiderers' Guild Practical Study Group (1984). Needlework School. QED Publishers. ISBN 0-89009-785-2.

- Gillow, John; Bryan Sentance (1999). World Textiles. Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-2621-5.

- Lemon, Jane (2004). Metal Thread Embroidery. Sterling. ISBN 0-7134-8926-X.

- Levey, S. M.; D. King (1993). The Victoria and Albert Museum's Textile Collection Vol. 3: Embroidery in Britain from 1200 to 1750. Victoria and Albert Museum. ISBN 1-85177-126-3.

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, (2005). Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-123-6.

- Quinault, Marie-Jo (2003). Filet Lace, Introduction to the Linen Stitch. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4120-1549-9.

- Readers Digest (1979). Complete Guide to Needlework. Readers Digest. ISBN 0-89577-059-8.

- van Niekerk, Di (2006). A Perfect World in Ribbon Embroidery and Stumpwork. ISBN 1-84448-231-6.

- Vogelsang, Gillian; Willem Vogelsang, editors (2015). TRC Needles. The TRC Digital Encyclopaedia of Decorative Needlework. Textile Research Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands.

- Wilson, David M. (1985). The Bayeux Tapestry. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-25122-3.

External links