Chinese armour

Chinese armour was predominantly lamellar from the Warring States period (481 BC - 221 BC) onward, prior to which animal parts such as rhinoceros hide, leather, and turtle shells were used for protection. Lamellar armour was supplemented by scale armour starting from the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) forward, partial plate armour from the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589), and mail and mountain pattern armour from the Tang dynasty (618–907). During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), brigandine began to supplant lamellar armour and was used to a great degree into the Qing dynasty (1644–1912.). By the 19th century most Qing armour, which was of the brigandine type, were purely ceremonial, having kept the outer studs for aesthetic purposes, and omitted the protective metal plates.

Ancient armour

Shang dynasty (c. 1600 BC–c. 1046 BC)

During the Shang dynasty armour consisted of breastplates made of shell tied together. Later on bronze became popular and bronze helmets appeared. Initially, armour was exclusively for nobles; regular folks had no protection except for a leather covered bamboo shield.[1]

Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 BC–256 BC)

Armour in the Zhou dynasty consisted of either a sleeveless coat of rhinoceros or buffalo hide, or leather scale armour. Helmets were largely similar to Shang predecessors but less ornate. Chariot horses were sometimes protected by tiger skins.[2]

Warring States (c. 475 BC–221 BC)

In the 4th century BC, rhinoceros armour was still used. In the following passage Guan Zhong advises Duke Huan of Qi to convert punishments to armour and weapons:

Ordain that serious crimes are to be redeemed with a suit of rhinoceros armour and one halberd, and minor crimes with a plaited leather shield and one halberd. Misdemeanours are to be punished with [a fine of] a quota of metal [jin fen 金分], and doubtful cases are to be pardoned. A case should be delayed for investigation for three [days] without allowing arguments or judgements; [by the time] the case is judged [the subject will have produced] one bundle of arrows. Good metal [mei jin 美金] should be cast into swords and halberd[-heads] and tested on dogs and horses, while poorer metal [e jin 惡金] should be cast into agricultural implements and tested on earth.[3]

— Guan Zhong

Ferrous metallurgy

However, by the mid-4th century BC, lamellar armour of leather, bronze and iron appeared. Lamellar consisted of individual armour pieces that were either riveted or laced together to form a suit of armour.[4]

In the 3rd century BC, both iron weapons and armour became more common. According to the Xunzi, "the hard iron spears of Wan (宛) [a city in Chu, near modern Nanyang (南陽), Henan] are as cruel as wasps and scorpions."[5] Iron weapons also gave Chinese armies an edge over barbarians. Han Fei recounts that during a battle with the Gonggong (共工) tribe, "the iron-tipped lances reached the enemy, and those without strong helmets and armour were injured."[6] As a result of the increasing effectiveness of iron weapons and armour, shields and axes became less common.[7] The efficiency of crossbows however outpaced any progress in defensive armour. It was considered a common occurrence in ancient China for commoners or peasants to kill a lord with a well aimed crossbow bolt, regardless of whatever armour he might have been wearing at the time.[8]

Shun taught the ways of good government for the following three years, and then took up shield and battle-ax and performed the war dance, and the Miao submitted. But in the war with the Gonggong, men used iron lances with steel heads that reached to the enemy, so that unless one was protected by a stout helmet and armor he was likely to be wounded. Hence shields and battle-axes served for ancient times, but no longer serve today. So I say that as circumstances change the ways of dealing with them alter too.[9]

— Han Fei

Armour was mostly restricted to elite guard units and each state distributed armour in their own ways. The state of Chu favorited elite armoured crossbow units known for their endurance, and were capable of marching 160km 'without resting.'[4] Wei's elite forces were capable of marching over 40km in one day while wearing heavy armour, a large crossbow with 50 bolts, a helmet, a side sword, and three days worth of rations. Those who met these standards earned an exemption from corvée labor and taxes for their entire family.[10]

According to Su Qin, the state of Han made the best weapons, capable of cleaving through the strongest armour, shields, leather boots and helmets.[11] Their soldiers wore iron facemasks.[4]

The Qin calculated fines in terms of one or two coats of armour, lower crimes in terms of shields, and the lowest in terms of coins.[12] Qin soldiers sometimes threw off their armour and engaged in fast charges.[13]

By the end of the 3rd century BC at least a few horsemen wore armour of some kind.[4]

Warring States bronze helmet

Warring States bronze helmet Warring States helmet

Warring States helmet Warring States helmet

Warring States helmet Warring States helmet

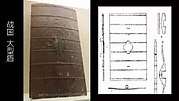

Warring States helmet Warring States rectangular shield (91.8cm tall, 49.6cm wide)

Warring States rectangular shield (91.8cm tall, 49.6cm wide) Qin shield (35.6cm tall, 23.5cm wide, 0.4cm thick)

Qin shield (35.6cm tall, 23.5cm wide, 0.4cm thick) Qin stone armour

Qin stone armour

Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD)

Han dynasty armour was largely the same as the Qin dynasty with minor variations. Infantry wore suits of rawhide, hardened leather, or iron lamellar armour and caps or iron helmets. Some riders wore armour and carried shields but substantial horse armour is not attested to until the late 2nd century.[14]

| Item | Inventory | Imperial Heirloom |

|---|---|---|

| Jia armour | 142,701 | 34,265 |

| Kai armour | 63,324 | |

| Thigh armour | 10,563 | |

| Iron thigh armour | 256 | |

| Iron lamellar armour (pieces?) | 587,299 | |

| Helmets | 98,226 | |

| Horse armour | 5,330 | |

| Shields | 102,551 |

During the late 2nd century BC, the government created a monopoly on the ironworks, which may have caused a decrease in quality of iron and armour. Bu Shi claimed that the resulting products were inferior because they were made to meet quotas rather than for practical use. These monopolies as debated in the Discourses on Salt and Iron were abolished by the beginning of the 1st century AD. In 150 AD, Cui Shi made similar complaints about the issue of quality control in government production due to corruption: "...not long thereafter the overseers stopped being attentive, and the wrong men have been promoted by Imperial decree. Greedy officers fight over the materials, and shifty craftsmen cheat them... Iron [i.e. steel] is quenched in vinegar, making it brittle and easy to... [?] The suits of armour are too small and do not fit properly."[15]

Composite bows were considered effective against unarmoured enemies at 165 yards, and against armoured opponents at 65 yards.[16]

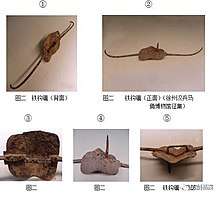

Two types of Han lamellar armour

Two types of Han lamellar armour Han iron scale or lamellar armour

Han iron scale or lamellar armour Han lamellar armour type 1

Han lamellar armour type 1 Han lamellar armour type 2

Han lamellar armour type 2 Han iron helmet

Han iron helmet Han shieldbearer

Han shieldbearer Han horseman with shield

Han horseman with shield

Three Kingdoms (220–280)

By the Three Kingdoms period many cavalrymen wore armour and some horses were equipped with their own armour as well. In one battle, the warlord Cao Cao boasted that with only ten sets of horse armour he had faced an enemy with three hundred sets.[17] The horse armour may however have just been partial frontal barding.[18]

Beginning in the 3rd century, references to "dark armour" (xuan kai or xuan jia 玄鎧/玄甲) appear. This is probably in reference to the association of high quality steel with black ferrous material.[19]

Jin dynasty and the Sixteen Kingdoms (265–439)

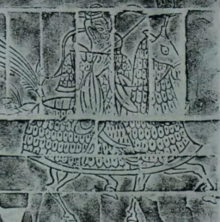

Cataphract-like horse armour appeared in northeastern China in the mid 4th century during the Eastern Jin dynasty, probably as a result of Xianbei influence. By the end of the 4th century murals depicting horse armour covering the entire body were found in tombs as far as Yunnan.[20]

Sources mention the capture of thousands of "armored horses" in a single battle.[17]

Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589)

During the Northern and Southern dynasties period (420-589), a style of armour called "cord and plaque" became popular, as did shields and long swords. "Cord and plaque" armour consisted of double breast plates in the front and back held in position by two shoulder straps and waist cords, in conjunction with the usual lamellar armour. "Cord and plaque" wearing figurines are also often depicted holding an oval or rectangular shield and a long sword.[21] Types of armour had also apparently become distinct enough for there to be separate categories for light and heavy armour.[22]

In the 6th century, Qimu Huaiwen introduced to Northern Qi the process of 'co-fusion' steelmaking, which used metals of different carbon contents to create steel. Apparently sabers made using this method were capable of penetrating 30 armour lamellae. It's not clear if the armour was of iron or leather.

Huaiwen made sabres [dao 刀] of 'overnight iron' [su tie 宿鐵]. His method was to anneal [shao 燒] powdered cast iron [sheng tie jing 生鐵精] with layers of soft [iron] blanks [ding 鋌, presumably thin plates]. After several days the result is steel [gang 剛]. Soft iron was used for the spine of the sabre, He washed it in the urine of the Five Sacrificial Animals and quench-hardened it in the fat of the Five Sacrificial Animals: [Such a sabre] could penetrate thirty armour lamellae [zha 札]. The 'overnight soft blanks' [Su rou ting 宿柔鋌] cast today [in the Sui period?] by the metallurgists of Xiangguo (襄國) represent a vestige of [Qiwu Huaiwen's] technique. The sabres which they make are still extremely sharp, but they cannot penetrate thirty lamellae.[23]

The Northern Wei employed the "iron-clad" Erzhu tribe who fought as armoured cavalry.[21]

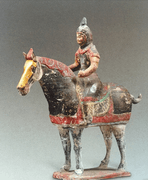

Northern Wei heavy cavalry funerary figurine.

Northern Wei heavy cavalry funerary figurine. Cavalry of Northern Wei.

Cavalry of Northern Wei. Northern Wei cavalry.

Northern Wei cavalry. Cavalry of the Southern dynasties.

Cavalry of the Southern dynasties. Western Wei cavalry

Western Wei cavalry A soldier of the Northern and Southern dynasties.

A soldier of the Northern and Southern dynasties. NS dynasties shieldbearers in "cord and plaque" armour

NS dynasties shieldbearers in "cord and plaque" armour

Medieval armour

Sui dynasty (581–618)

The Sui dynasty made prodigious use of heavy cavalry. Both men and horses were heavily armoured.[24]

The History of Sui provides an account of the "first cavalry battalions" of the dynasty's 24 armies. They wore "bright-brilliant" (mingguang) armour made of decarburized steel connected by dark green cords, their horses wore iron armour with dark green tassels, and they were distinguished by lion banners. Other battalions were also distinguished by their own colors, patterns, and flags, but neither the bright-brilliant armour or iron armour are mentioned.[25][26]

Tang dynasty (618–907)

By the Tang dynasty it was possible for armour to provide immense personal protection. In one instance Li Shimin's cousin, Li Daoxuan, was able to cut his way through the entire enemy mass of Xia soldiers and then cut his way back again, repeating the operation several times before the battle was won, at which point he had so many arrows sticking out of his armour that he looked like a "porcupine."[27] The effective range of a composite bow against armoured troops in this era was considered to be around 75 to 100 yards.[28]

Infantry armour became more common in the Tang era and roughly 60 percent of active soldiers were equipped with armour of some kind.[29] Armour could be manufactured natively or captured as a result of war. For instance 10,000 suits of iron armour were captured during the Goguryeo–Tang War.[30] Armour and mounts, including pack animals, were supplied by the state through state funds, and thus considered state property. Private ownership of military equipment such as horse armour, long lances, and crossbows was prohibited. Possession was taken as intent of rebellion or treason.[31] The army staff kept track of armour and weapons with detailed records of items issued. If a deficiency was discovered, the corresponding soldier was ordered to pay restitution.[32] The state also provided clothing and rations for border garrisons and expeditionary armies. Soldiers not on active duty were expected to pay for themselves, although "professional" soldiers were given tax exemptions.[33]

Li Shimin's elite cavalry forces were known to have worn distinctive black "iron clad" armour,[34] but heavy cavalry declined as Turkic influence became more prevalent and light cavalry became the dominant mode of mounted warfare. Tang expeditionary forces to Central Asia preferred a mixture of light and heavy Chinese horse archers. After the An Lushan rebellion of the mid 9th century and losing the northwestern pastures to the Tibetans, Chinese cavalry almost disappeared altogether as a relevant military force.[35] Many southern horses were considered too small or frail to carry an armoured soldier.[36]

Mail was already known to the Chinese since they first encountered it in 384 AD when their allies in the nation of Kuchi arrived wearing "armor similar to chains". However they did not procure a suit of mail until 718 AD when Central Asians presented to the Tang emperor a coat of "link armour". Mail was never used in any significant numbers (typically belonging to high ranks and those who could afford it) and the dominant form of armour continued to be lamellar. [37]

Tang cavalry figurines

Tang cavalry figurines Tang cavalry figurine

Tang cavalry figurine Tang cavalry figurine

Tang cavalry figurine Tang soldier wearing lamellar armour

Tang soldier wearing lamellar armour Tang soldier in a mural

Tang soldier in a mural Tang soldier with horse

Tang soldier with horse

Mountain pattern armour

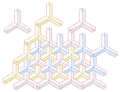

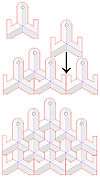

References to mountain pattern armour (Chinese: 山文铠; pinyin: shānwénkǎi) appear as early as the Tang dynasty, but historical texts provide no explanation or diagram of how it actually worked. There are also no surviving examples of it. Everything that is known about mountain pattern armour comes from paintings and statues, typically of the Song and Ming periods. It is not unique to China and has been found in depictions in Korea, Vietnam, Japan, and even Thailand, however non-religious depictions are limited to only China, Korea, and Vietnam. Reconstruction projects of this type of armour have largely failed to produce good results.[38]

The current theory is that this type of armour is made from a multitude of small pieces of iron or steel shaped like the Chinese character for the word "mountain" (山). The pieces are interlocked and riveted to a cloth or leather backing. It covers the torso, shoulders and thighs while remaining comfortable and flexible enough to allow movement. Also during this time, senior Chinese officers used mirror armour (Chinese: 护心镜; pinyin: hùxīnjìng) to protect important body parts, while cloth, leather, lamellar, and/or Mountain pattern armor were used for other body parts. This overall design was called "shining armor" (Chinese: 明光甲; pinyin: míngguāngjiǎ).[39]

There is an alternative theory that mountain pattern armour is simply a result of very stylistic depictions of mail armour, but known depictions of mail armour in Chinese art do not match with mountain pattern armour either.[40]

Scale armor with overlapping star-shaped pieces

Scale armor with overlapping star-shaped pieces Scale armor with interlocking mountain-shaped pieces

Scale armor with interlocking mountain-shaped pieces Tang tomb guardians wearing mountain pattern armour

Tang tomb guardians wearing mountain pattern armour Tang tomb guardian with mountain pattern armour

Tang tomb guardian with mountain pattern armour Tang soldier wearing mail and mountain pattern armour

Tang soldier wearing mail and mountain pattern armour Close up view of the Ming dynasty painting "Departure Herald" showing riders wearing lamellar and mountain pattern armour

Close up view of the Ming dynasty painting "Departure Herald" showing riders wearing lamellar and mountain pattern armour A statue of a deity wearing mountain pattern armour

A statue of a deity wearing mountain pattern armour Close up mountain pattern armour of a statue

Close up mountain pattern armour of a statue Ming statue wearing mail armour weave

Ming statue wearing mail armour weave Ming depiction of mail armour - it looks like scale, but this was a common artistic convention. The text says "steel wire connecting ring armour."

Ming depiction of mail armour - it looks like scale, but this was a common artistic convention. The text says "steel wire connecting ring armour."

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960)

Paper armour

During the wars between the Later Zhou and Southern Tang, civilians on the Tang side formed "White Armor Armies", named after the white paper armour they wore. These Tang civilian armies experienced some success in driving off small contingents of Zhou forces but avoided confrontation with the larger army.[41] The White Armour militia army was later revived to fight against the Song dynasty, but they were ineffective and disbanded.[42]

Later Ming texts provide descriptions of paper armour. One version was made of silk paper and functioned as a gambeson, worn under other armour or by itself. Silk paper could also be used for arm guards. Another version used thicker, more flexible paper, hammered soft, and fastened with studs. It's said that this type of paper armour performed better when soaked with water.[43]

Paper armour was still worn by the Hui people in Yunnan in the late 19th century. Bark paper armour in layers of thirty to sixty sheets in addition to silk and cotton was considered to be fairly good protection against musket balls and bayonets, which got stuck in the layers of paper, but not breech loading rifles at close quarters.[44]

Silk paper armour

Silk paper armour Paper arm guard

Paper arm guard Sleeved paper armour

Sleeved paper armour Barbarian paper armour

Barbarian paper armour

Liao dynasty (907–1125)

The Khitans of the Liao dynasty employed heavy armoured cavalry as the core of their army. In battle they arrayed light cavalry in the front and two layers of armoured cavalry in the back. Even foragers were armoured.[45]

Song dynasty (960–1279)

During the Song dynasty (960–1279) it became fashionable to create warts on pieces of armour to imitate cold forged steel, a product typically produced by non-Han people in modern Qinghai. Warts created from cold work were actually spots of higher carbon in the original steel, thus aesthetic warts on non-cold forged steel served no purpose. According to Shen Kuo, armour constructed of cold forged steel was impenetrable to arrows shot at a distance of 50 paces. Even if the arrow happened to hit a drill hole, the arrowhead was the one which was ruined.[46] However crossbows were still prized for their ability to penetrate heavy armour.[47]

The History of Song notes that Song "tools of war were exceedingly effective, never before seen in recent times,"[48] and "their weapons and armor were very good",[48] but "their troops weren't always effective."[48]

Lamellar armoured axe wielder

Lamellar armoured axe wielder Song dynasty soldiers wearing lamellar and mountain pattern armour.

Song dynasty soldiers wearing lamellar and mountain pattern armour. Song guards with lamellar armour

Song guards with lamellar armour Song soldiers in lamellar armour

Song soldiers in lamellar armour Song statue with mountain pattern armour

Song statue with mountain pattern armour Pavise

Pavise

Western Xia (1038–1227)

The Western Xia made modest use of heavy cavalry, of which it had 3,000 at its height.[49]

Jurchen Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

The Jurchens had a reputation for making high quality armour and weapons.[49] Both metal and quilted armour were worn by Jurchens. The Jurchen army was organized into units of a thousand and a hundred. Every hundred was composed of two fifty men social and economic units called punian. Each punian was supposed to have 20 men equipped with armour and lances or halberds. These 20 men formed a standard two rank five deep battle formation while the others formed three ranks of archers.[50]

In 1232 the Jurchens used cast iron bombs against the Mongols at the siege of Kaifeng. The History of Jin states that the fire created by the blast could penetrate even iron armour.[51]

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

According to Meng Hong, the reason for the Mongols' success was that they possessed more iron than previous steppe peoples.[52]

Both Chinese and European sources concur that Mongols wore substantial armour capable of stopping arrows. A Song source notes that one way to pierce heavily clad Mongol warriors was to use small arrows capable of entering the eye slits of their helmet.[53] According to Thomas the Archdeacon, Mongol arrows were capable of penetrating all known types of armour at the time, but their own leather armour could withstand the arrows of their enemies. However he also mentions that the Mongols feared crossbows.[54]

- Yuan brigandine

Yuan mail

Yuan mail Yuan mail coif

Yuan mail coif- Yuan helmet

- Yuan helmet

- Yuan helmet

Late imperial armour

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

During the Ming dynasty, most soldiers did not wear armour, which was reserved for officers and a small portion of the several hundred thousand strong army.[55] Horse armour was only used for a small portion of cavalry, which was itself a minute portion of the Ming army.[56]

Brigandine armour was introduced during the Ming era and consisted of riveted plates covered with fabric.[56]

Partial plate armour in the form of a cuirass sewn together with fabric is mentioned in the Wubei Yaolue, 1638. It's not known how common plate armour was during the Ming dynasty, and no other source mentions it.[57]

Although armour never lost all meaning during the Ming dynasty, it became less and less important as the power of firearms became apparent. It was already acknowledged by the early Ming artillery officer Jiao Yu that guns "were found to behave like flying dragons, able to penetrate layers of armor."[58] Fully armoured soldiers could and were killed by guns. The Ming Marshall Cai was one such victim. An account from the enemy side states, "Our troops used fire tubes to shoot and fell him, and the great army quickly lifted him and carried him back to his fortifications."[59] It's possible that Chinese armour had some success in blocking musket balls later on during the Ming dynasty. According to the Japanese, during the Battle of Jiksan, the Chinese wore armour and used shields that were at least partially bulletproof.[60] Frederick Coyett later described Ming lamellar armour as providing complete protection from "small arms", although this is sometimes mistranslated as "rifle bullets".[61] English literature in the early 19th century also mentions Chinese rattan shields that were "almost musket proof",[62] however another English source in the late 19th century states that they did nothing to protect their users during an advance on a Muslim stronghold, in which they were all invariably shot to death.[44]

Some were armed with bows and arrows hanging down their backs ; others had nothing save a shield on the left arm and a good sword in the right hand ; while many wielded with both hands a formidable battle-sword fixed to a stick half the length of a man. Everyone was protected over the upper part of the body with a coat of iron scales, fitting below one another like the slates of a roof; the arms and legs being left bare. This afforded complete protection from rifle bullets (mistranslation-should read "small arms") and yet left ample freedom to move, as those coats only reached down to the knees and were very flexible at all the joints. The archers formed Koxinga's best troops, and much depended on them, for even at a distance they contrived to handle their weapons with so great skill that they very nearly eclipsed the riflemen. The shield bearers were used instead of cavalry. Every tenth man of them is a leader, who takes charge of, and presses his men on, to force themselves into the ranks of the enemy. With bent heads and their bodies hidden behind the shields, they try to break through the opposing ranks with such fury and dauntless courage as if each one had still a spare body left at home. They continually press onwards, notwithstanding many are shot down ; not stopping to consider, but ever rushing forward like mad dogs, not even looking round to see whether they are followed by their comrades or not. Those with the sword-sticks—called soapknives by the Hollanders—render the same service as our lancers in preventing all breaking through of the enemy, and in this way establishing perfect order in the ranks ; but when the enemy has been thrown into disorder, the Sword-bearers follow this up with fearful massacre amongst the fugitives.[61]

— Frederick Coyett

Rocket handlers often wore heavy armour for extra protection so that they could fire at close range.[63]

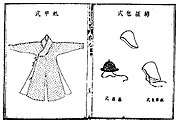

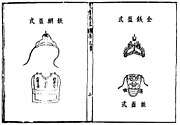

Ming helmet, breastplate, and mask from the Wubei Yaolue

Ming helmet, breastplate, and mask from the Wubei Yaolue Ming arm guards, thigh armour, and back plate from the Wubei Yaolue

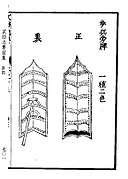

Ming arm guards, thigh armour, and back plate from the Wubei Yaolue Ming breast and back plates

Ming breast and back plates Ming breastplate

Ming breastplate Ming helmet

Ming helmet Ming shieldbearer

Ming shieldbearer

Qing dynasty (1636–1912)

In the 17th century the Qing army was equipped with both lamellar and brigandine armour.[64]

During the 18th century, the Qianlong Emperor said, "Our old Manchu customs respect righteousness and revere justice. Young and old, none are ashamed to fight for them. But after enjoying such a long period of peace, inevitably, people want to avoid putting on armor and joining the ranks of war."[65]

By the 19th century most Qing armour were purely for show. They kept the outer studs of brigandine armour for aesthetic purposes but omitted the protective iron plates.[66] According to one English source in the late 19th century, only the emperor's immediate body guard wore armour of any kind, and these guards were all nobles of the imperial family.[67]

Qing mail

Qing mail Qing mail

Qing mail A Manchu in mail armour.

A Manchu in mail armour. A Manchu officer in brigandine armour.

A Manchu officer in brigandine armour. Qing brigandine

Qing brigandine The Qianlong Emperor in ceremonial armour

The Qianlong Emperor in ceremonial armour Su Yuanchun, who fought in the Sino-French War (1884-1885)

Su Yuanchun, who fought in the Sino-French War (1884-1885)

Armour gallery

Shang bronze helmet

Shang bronze helmet Warring States leather armour

Warring States leather armour.jpg) Qin officer

Qin officer Han bronze helmet

Han bronze helmet Han iron scale armour

Han iron scale armour Nanyue iron lamellar armour

Nanyue iron lamellar armour Han lamellae

Han lamellae Sui soldier wearing cord and plaque armour

Sui soldier wearing cord and plaque armour Tang warrior wearing cord and plaque armour

Tang warrior wearing cord and plaque armour Tang sculpture wearing a tiger cap and mountain pattern armour

Tang sculpture wearing a tiger cap and mountain pattern armour Song axeman depicted with mail and lamellar armour.

Song axeman depicted with mail and lamellar armour. Jurchen Jin lamellar armour and helmet

Jurchen Jin lamellar armour and helmet Ming lamellar and plaque armour

Ming lamellar and plaque armour Ming brigandine

Ming brigandine Ming mail

Ming mail Ming phoenix helmet

Ming phoenix helmet Ming lamellar greaves

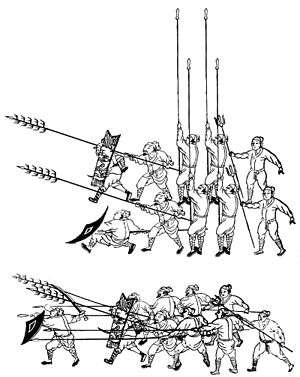

Ming lamellar greaves Ming pikemen wearing brigandine

Ming pikemen wearing brigandine Late Southern Ming lamellar armour

Late Southern Ming lamellar armour Late Southern Ming lamellar armour

Late Southern Ming lamellar armour Qing brigandine

Qing brigandine

Cavalry armour gallery

Qin cavalry

Qin cavalry- Han cavalry

Han cavalry

Han cavalry Evolution of Chinese saddles from left to right: Warring States, Western Han, Late Western Han, Eastern Han, Western Jin, Eastern Jin, Northern Qi, Tang.

Evolution of Chinese saddles from left to right: Warring States, Western Han, Late Western Han, Eastern Han, Western Jin, Eastern Jin, Northern Qi, Tang. Western Jin horse armour and mounting stirrup

Western Jin horse armour and mounting stirrup Western Jin horse figurine

Western Jin horse figurine Former Yan cavalry in procession

Former Yan cavalry in procession Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry Northern Yan chanfron

Northern Yan chanfron Northern Yan chanfron

Northern Yan chanfron Cavalry of the Southern dynasties

Cavalry of the Southern dynasties Western Wei cavalry

Western Wei cavalry Northern Qi cavalry

Northern Qi cavalry Khitan cavalry

Khitan cavalry Tang cavalry

Tang cavalry Song cavalry

Song cavalry Jurchen cavalry

Jurchen cavalry Yuan cavalry

Yuan cavalry Ming cavalry

Ming cavalry- Qing cavalry

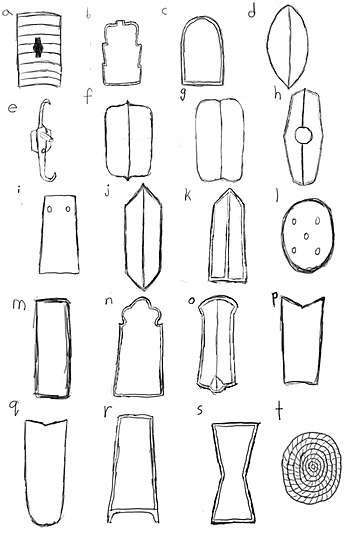

Shield gallery

Warring States shield (94.2cm tall, 60cm wide, 0.3cm thick)

Warring States shield (94.2cm tall, 60cm wide, 0.3cm thick) Warring States shield (46.8cm tall)

Warring States shield (46.8cm tall) Warring States shield (92.5cm tall, 55cm wide)

Warring States shield (92.5cm tall, 55cm wide) Warring States shield (64.5cm tall, 45.5cm wide, 0.7cm thick)

Warring States shield (64.5cm tall, 45.5cm wide, 0.7cm thick) Han shieldsmen tomb figurines

Han shieldsmen tomb figurines Restored Han iron shield

Restored Han iron shield Han shieldbearer

Han shieldbearer Han hook shield

Han hook shield Three Kingdoms shieldbearer

Three Kingdoms shieldbearer Former Yan shieldbearers

Former Yan shieldbearers NS dynasties shieldbearer

NS dynasties shieldbearer Northern Qi shield holder

Northern Qi shield holder NS dynasties shieldbearer

NS dynasties shieldbearer NS dynasties shieldbearer

NS dynasties shieldbearer Tang shieldbearers

Tang shieldbearers Tang cavalry shield

Tang cavalry shield Tang shieldbearer

Tang shieldbearer Tang soldier with shield

Tang soldier with shield Tang shieldbearer

Tang shieldbearer Northern Song soldiers with shields

Northern Song soldiers with shields Dali shieldbearer

Dali shieldbearer SEAsian depiction of Chinese mercenaries

SEAsian depiction of Chinese mercenaries.jpg) Ming "wolf troops" holding shields

Ming "wolf troops" holding shields Ming soldiers with shields

Ming soldiers with shields Ming shield fence

Ming shield fence Ming shields: 1. Hand 2. Swallowtail 3. Pushing

Ming shields: 1. Hand 2. Swallowtail 3. Pushing Ming "rattan" shield

Ming "rattan" shield Ming shield with fire arrow holders

Ming shield with fire arrow holders Ming shield equipped with fire lances

Ming shield equipped with fire lances Ming shieldbearers (bottom left)

Ming shieldbearers (bottom left) Ming soldiers with rattan shields

Ming soldiers with rattan shields Ming shields in Mandarin Duck Formation

Ming shields in Mandarin Duck Formation Qing soldiers with shields

Qing soldiers with shields

See also

References

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 24.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 4 Peers 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 116.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 117.

- ↑ Wager 2008, p. 117.

- ↑ Robinson 2004, p. 10.

- ↑ Han 2003, p. 101.

- ↑ Lewis 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Peers 2013, p. 60.

- ↑ Twitchett 2008, p. 50.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 41.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 75.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 225.

- ↑ Crespigny 2017, p. 159.

- 1 2 Graff 2002, p. 42.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 83.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 322.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 91.

- 1 2 Peers 2006, p. 94.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 99.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 256.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 115.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 147.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 158.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 173.

- ↑ Graff 2016, p. 51.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 193.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 197.

- ↑ Graff 2016, p. 41.

- ↑ Graff 2016, p. 106.

- ↑ Graff 2016, p. 39.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 176.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 116.

- ↑ Graff 2016, p. 161.

- ↑ Liu, Yonghua (刘永华) (September 2003), Ancient Chinese Armour (中国古代军戎服饰), Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House (上海古籍出版社), p. 174, ISBN 7-5325-3536-3

- ↑ The myths of Shan Wen Kia, retrieved 21 March 2018

- ↑ Liu, Yonghua (刘永华) (September 2003), Ancient Chinese Armour (中国古代军戎服饰), Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House (上海古籍出版社), pp. 63–64, ISBN 7-5325-3536-3

- ↑ The myths of Shan Wen Kia, retrieved 21 March 2018

- ↑ Lorge 2015, p. 84.

- ↑ Kurz 2011, p. 106.

- ↑ Paper armours of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 19 May 2018

- 1 2 Mesny 1896, p. 334.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 132.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 322-323.

- ↑ Wright 2005, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 Andrade 2016, p. 22.

- 1 2 Peers 2006, p. 135.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 137.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 143.

- ↑ Peers 2013, p. 149.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 48.

- ↑ Jackson 2005, p. 71.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 208.

- 1 2 Peers 2006, p. 185.

- ↑ ""Plate" armour of the Ming Dynasty". Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 57.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 67.

- ↑ Swope 2009, p. 248.

- 1 2 Coyet 1975, p. 51.

- ↑ Wood 1830, p. 159.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 184.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 216.

- ↑ Perdue 2005, p. 274.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 232.

- ↑ Mesy 1896, p. 334.

- Works cited

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7 .

- Coyet, Frederic (1975), Neglected Formosa: a translation from the Dutch of Frederic Coyett's Verwaerloosde Formosa

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2017), Fire Over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty, 23-220 AD, Brill

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Han, Fei (2003), Han Feizi: Basic Writings, Columbia University Press

- Jackson, Peter (2005), The Mongols and the West, Pearson Education Limited

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2011), China's Southern Tang Dynasty, 937-976, Routledge

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007), The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Lorge, Peter (2015), The Reunification of China: Peace through War under the Song Dynasty, Cambridge University Press

- Mesny, William (1896), Mesny's Chinese Miscellany

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Peers, Chris (2013), Battles of Ancient China, Pen & Sword Military

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005), China Marches West, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Robinson, K.G. (2004), Science and Civilization in China Volume 7 Part 2: General Conclusions and Reflections, Cambridge University Press

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2009), A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598, University of Oklahoma Press

- Twitchett, Denis (2008), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, Cambridge University Press

- Wood, W. W. (1830), Sketches of China

- Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press

- Wright, David (2005), From War to Diplomatic Parity in Eleventh Century China, Brill

- Ancient Chinese Armies: 1500-200BC C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Angus McBridge, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 0-85045-942-7

- Imperial Chinese Armies (1): 200BC-AD589 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Michael Perry, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-514-4

- Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590-1260AD C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Michael Perry, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-599-3

- Medieval Chinese Armies: 1260-1520 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by David Sque, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-254-4

- Late Imperial Chinese Armies: 1520-1840 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Christa Hook, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-655-8