Yongle Emperor

| Yongle Emperor 永樂帝 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Ming Empire | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 17 July 1402 – 12 August 1424 | ||||||||||||||||

| Coronation | 17 July 1402 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Jianwen Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Hongxi Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Born |

2 May 1360 Yingtian, Yuan Empire | ||||||||||||||||

| Died |

12 August 1424 (aged 64) Yumuchuan, Nuergan, Ming Empire | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial |

19 December 1424 Changling Mausoleum, Ming Dynasty Tombs, Beijing | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | House of Zhu | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Hongwu Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xiaocigao | ||||||||||||||||

| Yongle Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) "Yongle Emperor" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 永樂帝 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 永乐帝 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | “Perpetual Happiness” | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Yongle Emperor (Yung-lo in Wade–Giles; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424) — personal name Zhu Di (WG: Chu Ti) — was the third emperor of the Ming dynasty in China, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dynasty. He was originally enfeoffed as the Prince of Yan (燕王) in May 1370,[1] with the capital of his princedom at Beiping (modern Beijing). Amid the continuing struggle against the Mongols of the Northern Yuan dynasty, Zhu Di consolidated his own power and eliminated rivals such as the general Lan Yu. He initially accepted his father's appointment of his eldest brother Zhu Biao and then his nephew Zhu Yunwen as crown prince, but when Zhu Yunwen ascended the throne as the Jianwen Emperor and began executing and demoting his powerful uncles, Zhu Di found pretext for rising in rebellion against his nephew.[1] Assisted in large part by eunuchs mistreated by the Hongwu and Jianwen Emperors, who both favored the Confucian scholar-bureaucrats,[2] Zhu Di survived the initial attacks on his princedom and drove south to launch the Jingnan Campaign against the Jianwen Emperor in Nanjing. In 1402, he successfully overthrew his nephew and occupied the imperial capital, Nanjing, after which he was proclaimed Emperor and adopted the era name Yongle, which means "perpetual happiness".

Eager to establish his own legitimacy, Zhu Di voided the Jianwen Emperor's reign and established a wide-ranging effort to destroy or falsify records concerning his childhood and rebellion.[1] This included a massive purge of the Confucian scholars in Nanjing[1] and grants of extraordinary extralegal authority to the eunuch secret police.[2] One favorite was Zheng He, who employed his authority to launch major voyages of exploration into the South Pacific and Indian Oceans. The difficulties in Nanjing also led the Yongle Emperor to re-establish Beiping (present-day Beijing) as the new imperial capital. He repaired and reopened the Grand Canal and, between 1406 and 1420, directed the construction of the Forbidden City. He was also responsible for the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, considered one of the wonders of the world before its destruction by the Taiping rebels in 1856. As part of his continuing attempt to control the Confucian scholar-bureaucrats, the Yongle Emperor also greatly expanded the imperial examination system in place of his father's use of personal recommendation and appointment. These scholars completed the monumental Yongle Encyclopedia during his reign.

The Yongle Emperor died while personally leading a military campaign against the Mongols. He was buried in the Changling Tomb, the central and largest mausoleum of the Ming Dynasty Tombs located north of Beijing.

Youth

The Yongle Emperor was born Zhu Di (朱棣) on 2 May 1360, the fourth son of the new leader of the central Red Turbans, Zhu Yuanzhang. Zhu Yuanzhang would later rise to become the Hongwu Emperor, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty. According to surviving Ming historical records, Zhu Di's mother was the Hongwu Emperor's primary consort, Empress Ma, the view Zhu Di himself maintained. Some contemporaries maintained, however, that Zhu Di's mother was a non-Han Chinese concubine of his father's,[1][3] and that the official records were changed during his reign to list him as a son of the Empress Ma in order to sanction his succession on the "death" of the Jianwen Emperor.

The Mongols circulated a legend found in Altan Tobchi that the Yongle Emperor was the son of a Mongol empress who was pregnant with a Mongol child and captured after the Ming took over Beijing, and that she prayed that her pregnancy would be extended miraculously so the Hongwu Emperor would not suspect the child wasn't his, and that her pregnancy was extended by a miracle to 13 months instead of 9 months. This legend is disproven by the fact that it was only in 1368 when Beijing was captured and entered by the Hongwu Emperor (Zhu Yuanzhang) while the May 2, 1360 was the birthdate of the Yongle Emperor (Zhu Di) which was much earlier than the capture of Beijing.[4][5]

Zhu Di grew up as a prince in a loving, caring environment. His father supplied nothing but the best education and, trusting them alone, reestablished the old feudal principalities for his many sons. Zhu Di was created Prince of Yan, a location important for being both the former capital of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty and the frontline of battle against Northern Yuan dynasty, a successor state to the Yuan dynasty. When Zhu Di moved to Beiping, he found a city that had been devastated by famine and disease, but he worked with his father's general Xu Da – who was also his own father-in-law – to continue the pacification of the region. The official Ming histories portray a Zhu Di who impressed his father with his energy, daring, and leadership amid numerous successes; nonetheless, the Ming dynasty suffered numerous reverses during his tenure and the great victory at Buir Lake was won not by Zhu Di but by his brother's partisan Lan Yu. Similarly, when the Hongwu Emperor sent large forces to the north, they were not placed under Zhu Di's command.

Rise to power

The Hongwu Emperor was long-lived and survived his first heir, Zhu Biao, the Crown Prince. He worried about his succession and issued a series of dynastic instructions for his family, the Huang Ming Zu Xun. These instructions made it clear that the rule would pass only to children from the emperor's primary consort, excluding the Prince of Yan in favour of Zhu Yunwen, Zhu Biao's son.[1] When the Hongwu Emperor died on 24 June 1398, Zhu Yunwen succeeded his grandfather as the Jianwen Emperor. In direct violation of the dynastic instructions, the Prince of Yan attempted to mourn his father in Nanjing, bringing a large armed guard with him. The imperial army was able to block him at Huai'an and, given that three of his sons were serving as hostages in the capital, the prince withdrew in disgrace.[1]

The Jianwen Emperor's harsh campaign against his weaker uncles (dubbed 削蕃, lit. "Weakening the Marcher Lords") made accommodation much more difficult, however: Zhu Di's full brother, Zhu Su (朱橚), was arrested and exiled to Yunnan; the Prince of Dai Zhu Gui (朱桂) was reduced to a commoner; the Prince of Xiang Zhu Bai (朱柏) committed suicide under duress; the Princes of Qi and Min, Zhu Fu (朱榑) and Zhu Bian (朱楩) respectively, were demoted all within the later half of 1398 and the first half of 1399. Faced with certain hostility, Zhu Di pretended to fall ill and then "went mad" for a number of months before achieving his aim of freeing his sons from captivity to visit him in the north in June 1399. On 5 August, Zhu Di declared that the Jianwen Emperor had fallen victim to "evil counselors" (奸臣) and that the Hongwu Emperor's dynastic instructions obliged him to rise in arms to remove them, a conflict known as the Jingnan Campaign.[1]

In the first year, Zhu Di survived the initial assaults by superior forces under Geng Bingwen (耿炳文) and Li Jinglong (李景龍) thanks to superior tactics and capable Mongol auxiliaries. He also issued numerous justifications for his rebellion, including questionable claims to have been the son of Empress Ma and bold-faced lies that his father had attempted to name him as the rightful heir, only to be thwarted by bureaucrats scheming to empower Zhu Biao's son. Whether because of this propaganda or for personal motives, Zhu Di began to receive a steady stream of turncoat eunuchs and generals who provided him with invaluable intelligence allowing a hit-and-run campaign against the imperial supply depots along the Grand Canal. By 1402, he knew enough to be able to avoid the main hosts of the imperial army while sacking Xuzhou, Suzhou, and Yangzhou. The betrayal of Chen Xuan gave him the imperial army's Yangtze River fleet; the betrayal of Li Jinglong and the prince's half-brother Zhu Hui (朱橞) opened the gates of Nanjing on 13 July. Amid the disorder, the imperial palace quickly caught fire: Zhu Di enabled his own succession by claiming three bodies – charred beyond recognition – as the Jianwen emperor, his consort, and their son but rumours circulated for decades that the Jianwen Emperor had escaped in disguise as a Buddhist monk.[1][6][7]

Having captured the capital, Zhu Di now left aside his former arguments about rescuing his nephew from evil counsel and voided the Jianwen Emperor's entire reign, taking 1402 as the 35th year of the Hongwu era.[1] His own brother Zhu Biao, whom the Jianwen Emperor had posthumously elevated to emperor, was now posthumously demoted; Zhu Biao's surviving two sons were demoted to commoners and placed under house arrest; and the Jianwen Emperor's surviving younger son was imprisoned and hidden for the next 55 years. After a brief show of humility where he repeatedly refused offers to take the throne, Zhu Di accepted and proclaimed that the next year would be the first year of the Yongle era. On 17 July 1402, after a brief visit to his father's tomb, Zhu Di was crowned emperor of the Ming Empire at the age of 42. He would spend most of his early years suppressing rumours and outlaws.

Becoming the emperor

With many scholar-bureaucrats in Nanjing refusing to recognise the legitimacy of his claim to the throne, the Yongle Emperor began a thorough purge of them and their families, including women and children. Other supporters of the Jianwen Emperor's regime were extirpated throughout the country, while a reign of terror was seen due to eunuchs settling scores with the two prior administrations.[2]

Chinese law had long allowed for the execution of families along with principals: The Classic of History records insubordinate officers being threatened with it as far back as the Shang dynasty. The Hongwu Emperor had fully restored the practice, punishing rebels and traitors with death by a thousand cuts as well as the death of their grandparents, parents, uncles and aunts, siblings by birth or by bond, children, nephews and nieces, grandchildren, and all cohabitants of whatever family,[8][9] although children were sometimes spared and women were sometimes permitted to choose slavery instead. Four of the purged scholars became known as the Four Martyrs, the most famous of whom was Fang Xiaoru, the former tutor to the Jianwen Emperor: threatened with execution of all nine degrees of his kinship, he fatuously replied "Never mind nine! Go with ten!" and – alone in Chinese history – he was sentenced to execution of 10 degrees of kinship: along with his entire family, every former student or peer of Fang Xiaoru that the Yongle Emperor's agents could find was also killed. It was said that as he died, cut in half at the waist, Fang used his own blood to write the character 篡 ("usurper") on the floor and that 872 other people were executed in the ordeal.

The Yongle Emperor followed traditional rituals closely and held many popular beliefs. He did not overindulge in the luxuries of palace life, but still used Buddhism and Buddhist festivals to help calm civil unrest. He stopped the warring between the various Chinese tribes and reorganised the provinces to best provide peace within the Ming Empire. The Yongle Emperor was said to be an "ardent Buddhist" by Ernst Faber.[10]

Due to the stress and overwhelming amount of thinking involved in running a post-rebellion empire, the Yongle Emperor searched for scholars to serve in his government. He had many of the best scholars chosen as candidates and took great care in choosing them, even creating terms by which he hired people. He was also concerned about the degeneration of Buddhism in China.

Reign

Relations with Tibet

Tibetan Buddhism was patronised by Yongle.[11][12]

In 1403, the Yongle Emperor sent messages, gifts, and envoys to Tibet inviting Deshin Shekpa, the fifth Gyalwa Karmapa of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, to visit the imperial capital – apparently after having a vision of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. After a long journey, Deshin Shekpa arrived in Nanjing on 10 April 1407 riding on an elephant towards the imperial palace, where tens of thousands of monks greeted him.

Deshin Shekpa convinced the Yongle Emperor that there were different religions for different people, which does not mean that one is better than the others. The Karmapa was very well received during his visit and a number of miraculous occurrences were reported. He also performed ceremonies for the imperial family. The emperor presented him with 700 measures of silver objects and bestowed the title of 'Precious Religious King, Great Loving One of the West, Mighty Buddha of Peace'.[13]

Aside from the religious matter, the Yongle Emperor wished to establish an alliance with the Karmapa similar to the one the 13th- and 14th-century Yuan khans had established with the Sakyapa.[14] He apparently offered to send armies to unify Tibet under the Karmapa but Deshin Shekpa demurred, as parts of Tibet were still firmly controlled by partisans of the former Yuan dynasty.[15]

Deshin Shekpa left Nanjing on 17 May 1408.[16] In 1410, he returned to Tsurphu where he had his monastery rebuilt following severe damage from an earthquake.

Selecting an heir

When it was time for him to choose an heir, the Yongle Emperor wanted to choose his second son, Zhu Gaoxu. Zhu Gaoxu had an athletic-warrior personality which contrasted sharply with his elder brother's intellectual and humanitarian nature. Despite much counsel from his advisers, the Yongle Emperor chose his older son, Zhu Gaozhi (the future Hongxi Emperor), as his heir apparent mainly due to advice from Xie Jin. As a result, Zhu Gaoxu became infuriated and refused to give up jockeying for his father's favour and refusing to move to Yunnan Province, where his princedom was located. He even went so far as to undermine Xie Jin's counsel and eventually killed him.

National economy and construction projects

After the Yongle Emperor's overthrow of the Jianwen Emperor, China's countryside was devastated. The fragile new economy had to deal with low production and depopulation. The Yongle Emperor laid out a long and extensive plan to strengthen and stabilise the new economy, but first he had to silence dissension. He created an elaborate system of censors to remove corrupt officials from office that spread such rumors. The emperor dispatched some of his most trusted officers to reveal or destroy secret societies, bandits, and loyalists to his other relatives. To strengthen the economy, he fought population decline by reclaiming land, using the most he could from the existing labour force, and maximising textile and agricultural production.

The Yongle Emperor also worked to reclaim production rich regions such as the Lower Yangtze Delta and called for a massive reconstruction of the Grand Canal. During his reign, the Grand Canal was almost completely rebuilt and was eventually moving imported goods from all over the world. The Yongle Emperor's short-term goal was to revitalise northern urban centres, especially his new capital at Beijing. Before the Grand Canal was rebuilt, grain was transferred to Beijing in two ways; one route was simply via the East China Sea, from the port of Liujiagang (near Suzhou); the other was a far more laborious process of transferring the grain from large to small shallow barges (after passing the Huai River and having to cross southwestern Shandong), then transferred back to large river barges on the Yellow River before finally reaching Beijing.[17] With the necessary tribute grain shipments of four million shi (one shi equal to 107 liters) to the north each year, both processes became incredibly inefficient.[17] It was a magistrate of Jining, Shandong who sent a memorandum to the Yongle Emperor protesting the current method of grain shipment, a request that the emperor ultimately granted.[18]

The Yongle Emperor ambitiously planned to move his capital to Beijing. According to a popular legend, the capital was moved when the emperor's advisers brought the emperor to the hills surrounding Nanjing and pointed out the emperor's palace showing the vulnerability of the palace to artillery attack.

The emperor planned to build a massive network of structures in Beijing in which government offices, officials, and the imperial family resided. After a painfully long construction time (1407–1420), the Forbidden City was finally completed and became the imperial capital for the next 500 years.

The Yongle Emperor finalised the architectural ensemble of his father's Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum in Nanjing by erecting a monumental "Square Pavilion" (Sifangcheng) with an eight-metre-tall tortoise-borne stele, extolling the merits and virtues of the Hongwu Emperor. In fact, the Yongle Emperor's original idea for the memorial was to erect an unprecedented stele 73 metres tall. However, due to the impossibility of moving or erecting the giant parts of that monuments, they have been left unfinished in Yangshan Quarry, where they remain to this day.[19]

Even though the Hongwu Emperor may have meant for his descendants to be buried near his own Xiaoling Mausoleum (this was how the Hongwu Emperor's heir apparent, Zhu Biao was buried), the Yongle Emperor's relocation of the capital to Beijing necessitated the creation of a new imperial burial ground. On the advice of fengshui experts, the Yongle Emperor chose a site north of Beijing, where he and his successors were to be buried. Over the next two centuries, thirteen emperors in total were laid to rest in the Ming Dynasty Tombs.

Religion and philosophy

The Yongle Emperor sponsored and created many cultural traditions. He promoted Confucianism and kept traditional ritual ceremonies with a rich cultural theme. His respect for classical culture was apparent. He commissioned his Grand Secretary, Xie Jin, to write a compilation of every subject and every known book of the Chinese. The massive project's goal was to preserve Chinese culture and literature in writing. The initial copy took 17 months to transcribe and another copy was transcribed in 1557. The book, named the Yongle Encyclopedia, is still considered one of the most marvellous human achievements in history, despite it being gradually lost by time.

The Yongle Emperor's tolerance of Chinese ideas that did not agree with his own philosophies was well known. He treated Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism equally (though he favoured Confucianism). Strict Confucianists considered him hypocritical, but his even-handed approach helped him win the support of the people and unify China. His love for Chinese culture sparked a sincere hatred for Mongol culture. He considered it rotten and forbade the use of popular Mongol names, habits, language, and clothing. Great lengths were taken by the Yongle Emperor to eradicate Mongol culture from China.

The Yongle Emperor called for the construction and repair of Islamic mosques during his reign. Two mosques were built by him, one in Nanjing and the other in Xi'an and they still stand today. Repairs were encouraged and the mosques were not allowed to be converted to any other use.[20][21]

Military campaigns

Wars against the Mongols

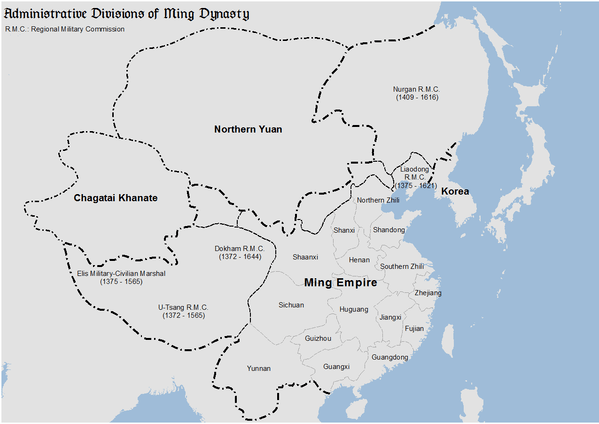

Mongol invaders were still causing many problems for the Ming Empire. The Yongle Emperor prepared to eliminate this threat. He mounted five military expeditions into the Mongol steppes and crushed the remnants of the Yuan dynasty that had fled north after being defeated by the Hongwu Emperor. He repaired the northern defences and forged buffer alliances to keep the Mongols at bay in order to build an army. His strategy was to force the Mongols into economic dependence on the Chinese and to launch periodic initiatives into Mongolia to cripple their offensive power. He attempted to compel Mongolia to become a Chinese tributary, with all the tribes submitting and proclaiming themselves vassals of the Ming Empire, and wanted to contain and isolate the Mongols. Through fighting, the Yongle Emperor learned to appreciate the importance of cavalry in battle and eventually began spending much of his resources to keep horses in good supply. The emperor spent his entire life fighting the Mongols. Failures and successes came and went, but it should be noted that after the emperor's second personal campaign against the Mongols, the Ming Empire was at peace for over seven years.

Tang Taizong was cited by Yongle as his model for being familiar with both China and the steppe people.[22]

The "Heavenly Qaghan" Tang Emperor Taizong was imitated by Yongle as was the Tang's multi-ethnic nature.[23]

Conquest of Vietnam

Vietnam was a significant source of difficulties during the Yongle Emperor's reign. In 1406, the emperor responded to several formal petitions from members of the Trần dynasty, however on arrival to Vietnam, both the Trần prince and the accompanying Chinese ambassador were ambushed and killed. In response to this insult, the Yongle Emperor sent two armies led by Zhang Fu and Mu Sheng to conquer Vietnam. As the Ho royal family were all executed,[24]:112–113 Vietnam was integrated as a province of China, just as it had been up until 939. With the Ho monarch defeated in 1407, the Chinese began a serious and sustained effort to sinicise the population. All classical Vietnamese printing blocks, books and materials were burned. For this reason almost no vernacular chữ nôm texts survive from before the Ming invasion. Various ancient sites such as pagoda Bao Minh were looted and destroyed. On 2 December 1407, the Yongle Emperor gave orders to Zhang Fu that innocent Vietnamese were not to be harmed, ordering family members of rebels to be spared such as young males if they themselves were not involved in rebellion.[25] Efforts to colonize Vietnam into a Chinese province was met by fierce resistance, first from the Trần aristocrats who fought the Later Trần rebellion in the Red River Delta, and then from the frontier population among the Vietnamese and Muong people in mountainous Thanh Hoa and Nghe An provinces. In early 1418, Lê Lợi, who founded the Lê dynasty, started a major rebellion against Ming rule. By the time the Yongle Emperor died in 1424, the Vietnamese rebels under Lê Lợi's leadership had captured nearly the entire province. By 1427, the Xuande Emperor gave up the effort started by his grandfather and formally acknowledged Vietnam's independence on condition they accept vassal status.

Diplomatic missions and exploration of the world

As part of his desire to expand Chinese influence throughout the known world, the Yongle Emperor sponsored the massive and long term treasure voyages led by admiral Zheng He. While Chinese ships continued travelling to Japan, Ryukyu, and many locations in Southeast Asia before and after the Yongle Emperor's reign, Zheng He's expeditions were China's only major sea-going explorations of the world (although the Chinese may have been sailing to Arabia, East Africa, and Egypt since the Tang dynasty[27] or earlier). The first expedition was launched in 1405 (18 years before Henry the Navigator began Portugal's voyages of discovery). The expeditions were under the command of Zheng He and his associates (Wang Jinghong, Hong Bao, etc.). Seven expeditions were launched between 1405 and 1433, reaching major trade centres of Asia (as far as Tenavarai (Dondra Head), Hormuz and Aden) and northeastern Africa (Malindi). Some of the ships used were apparently the largest sail-powered wooden ships in human history.[28]

The Chinese expeditions were a remarkable technical and logistical achievement. The Yongle Emperor's successors, the Hongxi and Xuande Emperors, felt that the costly expeditions were harmful to the Ming Empire. The Hongxi Emperor ended further expeditions and the descendants of the Xuande Emperor suppressed much of the information about Zheng He's treasure voyages.

On 30 January 1406, the Yongle Emperor expressed horror when the Ryukyuans castrated some of their own children to become eunuchs to serve in the Ming imperial palace. The emperor said that the boys who were castrated were innocent and did not deserve castration, and he returned the boys to Ryukyu and instructed them not to send eunuchs again.[29]

In 1411, a smaller fleet, built in Jilin and commanded by another eunuch Yishiha, who was a Jurchen, sailed down the Sungari and Amur Rivers. The expedition established a Nurgan Regional Military Commission in the region, headquartered at the place the Chinese called Telin (特林; now the village of Tyr, Russia). The local Nivkh or Tungusic chiefs were granted ranks in the imperial administration. Yishiha's expeditions returned to the lower Amur several more times during the reigns of the Yongle and Xuande Emperors, the last one visiting the region in the 1430s.[30][31][32]

After the death of Timur, who intended to invade China, relations between the Ming Empire and Shakhrukh's state in Persia and Transoxania state considerably improved, and the states exchanged large official delegations on a number of occasions. Both the Ming Empire's envoy to Samarkand and Herat, Chen Cheng, and his counterpart, Ghiyasu'd-Din Naqqah, recorded detailed accounts of their visits to each other's states.

One of the Yongle Emperor's consorts was a Jurchen princess, which resulted in many of the eunuchs serving him being of Jurchen origin, notably Yishiha.[33][34]

The Yongle Emperor instituted a Ming governor on Luzon during Zheng He's voyages and appointed Ko-ch'a-lao (許柴佬; Xu Chailao) to that position in 1405.[35][36] China also had vassals among the leaders in the archipelago.[37][38] China attained ascendancy in trade with the area in the Yongle Emperor's reign.[39] The local rulers on Luzon were "confirmed" by the governor or "high officer" appointed by the Yongle Emperor.[40]

States in Luzon,[41][42] Sulu (under King Paduka Pahala),[40][43] Sumatra,[44] and Brunei[45][46] all established diplomatic relations with the Ming Empire and exchanged envoys and sent tribute to the Yongle Emperor.

The Yongle Emperor exchanged ambassadors with Shahrukh Mirza, sending Chen Cheng to Samarkand and Herat, and Shahrukh sent Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh to Beijing.

Death

On 1 April 1424, the Yongle Emperor launched a large campaign into the Gobi Desert to chase an army of fleeing Oirats. Frustrated at his inability to catch up with his swift opponents, Yongle fell into a deep depression and then into illness, possibly owing to a series of minor strokes. On 12 August 1424, the Yongle Emperor died. He was entombed in Changling (長陵), a location northwest of Beijing.

Legacy

Many have seen the Yongle Emperor as in a lifelong pursuit of power, prestige, and glory. He respected and worked hard to preserve Chinese culture by designing monuments such as the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, while undermining and expelling from Chinese society people from foreign cultures. He deeply admired and wished to save his father's accomplishments and spent a lot of time proving his claim to the throne. His reign was a mixed blessing for the Chinese populace. The Yongle Emperor's economic, educational, and military reforms provided unprecedented benefits for the people, but his despotic style of government set up a spy agency. Despite these negatives, he is considered an architect and keeper of Chinese culture, history, and statecraft and an influential ruler in Chinese history.

He is remembered very much for his cruelty, just like his father. He killed most of the Jianwen Emperor's palace servants, tortured many of his nephew's loyalists to death, killed or by other means badly treated their relatives.[47][48][49][50] His successor freed most of the survivors.

Family

- Parents:

- Zhu Yuanzhang (高皇帝 朱元璋; 1328 – 1398)

- Empress Ma (孝慈高皇后 馬秀英; 1332 – 1382), personal name Xiuying

- Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Xu (仁孝文皇后 徐儀華; 1362 – 1407), personal name Yihua

- Princess Yong'an (永安公主 朱玉英; 1377 – 1417), personal name Yuying

- Zhu Gaochi (仁宗 朱高熾; 1378 – 1425)

- Princess Yongping (永平公主; 1379 – 1444)

- Zhu Gaoxu (漢王 朱高煦; 1380 – 1426)

- Zhu Gaosui (趙簡王 朱高燧; 1383 – 1431)

- Princess Ancheng (安成公主; 1384 – 1443)

- Princess Xianning (咸寧公主; 1385 – 1440)

- Third rank consort Zhang (昭懿貴妃 張氏)

- Third rank consort Wang (昭獻貴妃 王氏; d. 1420)

- Fourth rank consort Wu (康穆惠妃 吳氏)

- Zhu Gaoxi (朱高爔; 1392)

- Fourth rank consort Gwon of Andong (恭獻賢妃 安東權氏; 1391 – 1410)

- Fourth rank consort Choi (康靖惠妃 崔氏; 1395 – 1424)

- Fourth rank consort Han of Cheongju (康惠惠妃 清州韓氏; d. 1424)

- Fourth rank consort Liu (昭順德妃 劉氏)

- Fourth rank consort Li (康懿順妃 李氏)

- Fourth rank consort Guo (惠穆順妃 郭氏)

- Fourth rank consort Zhang (貞靜順妃 張氏)

- Fourth rank consort Yu (忠敬賢妃 喻氏; d. 1421)

- Fourth rank consort Chen (恭順麗妃 陳氏)

- Fourth rank consort Yang (端靜淑妃 楊氏)

- Fourth rank consort Wang (恭和賢妃 王氏)

- Fourth rank consort Wang (昭肅賢妃 王氏)

- Fourth rank consort Wang (昭惠順妃 王氏)

- Fourth rank consort Qian (惠穆順妃 錢氏)

- Fourth rank consort Long (安順惠妃 龍氏)

- Unknown

- Princess Changning (常寧公主; 1387 – 1408)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Chan Hok-lam. "Legitimating Usurpation: Historical Revisions under the Ming Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424)". The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History. Chinese University Press, 2007. ISBN 9789629962395. Accessed 12 Oct 2012.

- 1 2 3 Crawford, Robert B. "Eunuch Power in the Ming Dynasty". T'oung Pao, 2d Series, Vol. 49, Livr. 3 (1961), pp. 115-148. Accessed 9 Oct 2012.

- ↑ Levathes, Louise. When China Ruled The Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne 1405–1433, p. 59. Oxford Univ. Press (New York), 1994.

- ↑ Louise Levathes (1994). When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne 1405-1433. Simon & Schuster. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-671-70158-1.

- ↑ Louise Levathes (2 December 2014). When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. Open Road Distribution. ISBN 978-1-5040-0736-8.

- ↑ Lü Bi (吕毖). A Short History of the Ming Dynasty (《明朝小史》), Vol. 3. (in Chinese)

- ↑ Gu Yingtai (谷應泰). Major Events in Ming History (《明史紀事本末》), Vol. 16. (in Chinese)

- ↑ Chinamonitor.org. "Examination of China's Death Penalty: Torture from the Time of the Ming" (《中国死刑观察--明初酷刑》). (in Chinese)

- ↑ Ni Zhengmao (倪正茂). An Exploration of Comparative Law (比较法学探析). China Legal Publishing (中国法制出版社), 2006.

- ↑ Ernst Faber (1902). Chronological handbook of the history of China: a manuscript left by the late Rev. Ernst Faber. Pub. by the General Evangelical Protestant missionary society of Germany. p. 196. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ↑ http://www.history.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/readings/robinson_culture_courtiers_ch.8.pdf

- ↑ https://www.sav.sk/journals/uploads/040214374_Slobodn%C3%ADk.pdf p 166.

- ↑ Brown, 34.

- ↑ Sperling, 283–284.

- ↑ Brown, 33–34.

- ↑ Sperling, 284.

- 1 2 Brook, 46–47.

- ↑ Brook, 47.

- ↑ Yang, Xinhua (杨新华); Lu, Haiming (卢海鸣) (2001), 南京明清建筑 (Ming and Qing architecture of Nanjing), 南京大学出版社 (Nanjing University Press), pp. 595–599, 616–617, ISBN 7-305-03669-2

- ↑ China archaeology and art digest, Volume 3, Issue 4. Art Text (HK) Ltd. 2000. p. 29. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Dru C. Gladney (1996). Muslim Chinese: ethnic nationalism in the People's Republic. Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 269. ISBN 0-674-59497-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Robinson, David M., Delimiting the Realm under the Ming Dynasty (PDF), p. 22

- ↑ http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ics/journal/articles/v60p299.pdf p. 304.

- ↑ Maspero, G., 2002, The Champa Kingdom, Bangkok: White Lotus Co., Ltd., ISBN 9747534991

- ↑ "Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource". Geoff Wade, translator. Singapore: Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press, National University of Singapore. p. 1014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ↑ Duyvendak, J.J.L. (1939), "The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century", T'oung Pao, Second Series, 34 (5): 402, JSTOR 4527170

- ↑ Based on descriptions of the coast from 860. Ronan, Colin; Needham, Joseph (1986), The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, 3, p. 133

- ↑ National Geographic, May 2004

- ↑ Wade, Geoff (July 1, 2007). "Ryukyu in the Ming Reign Annals 1380s-1580s" (PDF). Working Paper Series (93). Asia Research Institute National University of Singapore: 75. SSRN 1317152. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ L. Carrington Godrich, Chaoying Fang (editors), "Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644". Volume I (A-L). Columbia University Press, 1976. ISBN 0-231-03801-1. (Article on Ishiha, pp. 685–686)

- ↑ Tsai (2002), pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Shih-shan Henry Tsai (1996). The eunuchs in the Ming dynasty (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-7914-2687-4. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

While Hai Tong and Hou Xian were busy courting the Mongols and Tibetans, a Ming eunuch of Manchurian stock, Yishiha, also quietly carried the guidon in the exploration of Northern Manchuria and Eastern Siberia. In 1375, the Ming dynasty established the Liaodong Regional Military Commission at Liaoyang, using twenty-five guards (each guard consisted of roughly 5,600 soldiers) to control Southern Manchuria. In 1409, six years after the Yongle Emperor ascended the throne, he launched three campaigns to shore up Ming influence in the lower Amur River valley. The upshot was the establishment of the Nuerkan Regional Military Commission with several battalions (1,120 soldiers theoretically made up a battalion) deployed along the Songari, Ussuri, Khor, Urmi, Muling and Nen Rivers. The Nuerkan Commission, which parallelled that of the Liaodong Commission, was a special frontier administrations; therefore the Ming government permitted its commanding officers to transmit their offices to their sons and grandsons without any dimunition in rank. In the meantime, The Ming court periodically sent special envoys and inspectors to the region, making sure that the chiefs of various tribes remained loyal to the Ming emperor. But the one enboy who was most active and played the most significant role in the region was the eunuch Yishiha.

- ↑ Taisuke Mitamura (1970). Chinese eunuchs: the structure of intimate politics. C.E. Tuttle Co. p. 54. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Shih-shan Henry Tsai (1996). The eunuchs in the Ming dynasty (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-7914-2687-4. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

Yishiha belonged to the Haixi tribe of the Jurchen race. The Ming shi provides no background information on this Manchurian castrato except that Yishiha worked under two powerful early Ming eunuchs, Wang Zhen, and Cao Jixiang. It is also likely that Yishiha gained prominence by enduring the hard knocks of court politics and serving imperial concubines of Manchurian origin, as the Yongle Emperor kept Jurchen women in his harem. At any rate, in the spring of 1411, the Yongle Emperor commissioned Yishiha to vie for the heart and soul of the peoples in Northern Manchuria and Eastern Siberia. Yishiha led a party of more than 1,000 officers and soldiers who boarded twenty-five ships and sailed along the Amur River for several days before reaching the Nuerkan Command post. Nuerkan was located on the east bank of the Amur River, approximately 300 li from the river's entrance and 250 li form the present-day Russian town of Nikolayevka. Yishiha's immediate assignment was to confer titles on tribal chiefs, giving them seals and uniforms. He also actively sought new recruits to fill out the official ranks for the Regional Commission.17

- ↑ Ho 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Karnow 2010,

- ↑ Yust 1949, p. 75.

- ↑ Yust 1954, p. 75.

- ↑ "Philippine Almanac & Handbook of Facts" 1977, p. 59.

- 1 2 Villegas, Ramón N. (1983). Kayamanan: The Philippine Jewelry Tradition. Central Bank of the Philippines. p. 107. ISBN 9711039001. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Paz, Victor; Solheim, II, Wilhelm G., eds. (2004). Southeast Asian Archaeology: Wilhelm G. Solheim II Festschrift (illustrated ed.). University of the Philippines Press. p. 476. ISBN 9715424511. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Woods, Damon L. (2006). The Philippines: A Global Studies Handbook (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 16. ISBN 1851096752. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Finlay, Robert (2010). The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History. Volume 11 of California World History Library (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 226. ISBN 0520945387. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Reid, Anthony; Alilunas-Rodgers, Kristine, eds. (1996). Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast China and the Chinese. Contributor Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 26. ISBN 0824824466. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (1993). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680: Expansion and crisis, Volume 2. Volume 2 of Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680 (illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. p. 206. ISBN 0300054122. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Wink, André (2004). Indo-Islamic society: 14th - 15th centuries. Volume 3 of Al-Hind Series. BRILL. p. 238. ISBN 9004135618. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Bo Yang, 中國人史綱, ch.28

- ↑ 宋端儀, 立齋閑錄, vol.2

- ↑ 陸人龍, 型世言, ch.1

- ↑ 建文帝出亡宁德之谜揭秘八:建文帝出亡闽东金邶寺

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A.; Guerrero, Milagros (1975). History of the Filipino People (4 ed.). R. P. Garcia. ISBN 9712345386. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1962). Philippine History. Inang Wika Publishing Company. ISBN 9712345386. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Alip, Eufronio Melo (1954). Political and Cultural History of the Philippines, Volumes 1-2 (revised ed.). Alip & Sons. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Antonio, Eleanor D.; Dallo, Evangeline M.; Imperial, Consuelo M.; Samson, Maria Carmelita B.; Soriano, Celia D. (2007). Turning Points I' 2007 Ed (unabridged ed.). Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 9712345386. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Bishop, Carl Whiting (1942). War Background Studies. Contributor Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Bishop, Carl Whiting (1942). Origin of Far Astern Civilizations: A Brief Handbook, Issues 1-7. Contributor Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Brook, Timothy. (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0

- Brown, Mick. (2004). The Dance of 17 Lives: The Incredible True Story of Tibet's 17th Karmapa, p. 34. Bloomsbury Publishing, New York and London. ISBN 1-58234-177-X.

- Corpuz, Onofre D. (1957). The bureaucracy in the Philippines. Institute of Public Administration, University of the Philippines. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Demetrio, Francisco R. (1981). Myths and Symbols: Philippines (2 ed.). National Book Store. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Del Castillo y Tuazon, Antonio (1988). Princess Urduja, Queen of the Orient Seas: Before and After Her Time in the Political Orbit of the Shri-vi-ja-ya and Madjapahit Maritime Empire : a Pre-Hispanic History of the Philippines. A. del. Castillo y Tuazon. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Farwell, George (1967). Mask of Asia: The Philippines Today. Praeger. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Fitzgerald, Charles Patrick (1966). A concise history of East Asia. Praeger. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Ho, Khai Leong, ed. (2009). Connecting and Distancing: Southeast Asia and China (illustrated ed.). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9812308563. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Karnow, Stanley (2010). In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines (unabridged ed.). Random House LLC. ISBN 0307775437. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Krieger, Herbert William (1942). Peoples of the Philippines, Issue 4. Volume 3694 of Publication (Smithsonian Institution). Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Lucman, Norodin Alonto (2000). Moro Archives: A History of Armed Conflicts in Mindanao and East Asia. FLC Press. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Liao, Shubert S. C., ed. (1964). Chinese participation in Philippine culture and economy. Bookman. Archived from the original on Nov 9, 2006. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Manuel, Esperidion Arsenio (1948). Chinese Elements in the Tagalog Language: With Some Indication of Chinese Influence on Other Philippine Languages and Cultures, and an Excursion Into Austronesian Linguistics. Contributor Henry Otley Beyer. Filipiniana Publications. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Ostelius, Hans Arvid (1963). Islands of Pleasure: A Guide to the Philippines. G. Allen & Unwin. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Panganiban, José Villa; Panganiban, Consuelo Torres (1965). The literature of the Pilipinos: a survey (5 ed.). Limbagang Pilipino. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Panganiban, José Villa; Panganiban, Consuelo Torres- (1962). A Survey of the Literature of the Filipinos (4 ed.). Limbagang Pilipino. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Quirino, Carlos (1963). Philippine Cartography, 1320–1899 (2 ed.). N. Israel. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Ravenholt, Albert (1962). The Philippines: A Young Republic on the Move. Van Nostrand. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Sevilla, Fred; Balagtas, Francisco (1997). Francisco Balagtas and the roots of Filipino nationalism: life and times of the great Filipino poet and his legacy of literary excellence and political activism. Trademark Pub. Corp. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Spencer, Cornelia (1951). Seven Thousand Islands: The Story of the Philippines. Aladdin Books. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Sperling, Elliot. "The 5th Karma-pa and some aspects of the relationship between Tibet and the early Ming." In: Tibetan Studies in Honour of Hugh Richardson. Edited by Michael Aris and Aung San Suu Kyi, pp. 283–284. (1979). Vikas Publishing house, New Delhi.

- Tan, Antonio S. (1972). The Chinese in the Philippines, 1898–1935: A Study of Their National Awakening. R. P. Garcia Publishing Company. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Yust, Walter, ed. (1949). Encyclopædia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 9. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 9. Volume 9 of EncyclopÆdia Britannica: A New Survey of Universal Knowledge. Contributor Walter Yust. EncyclopÆdia Britannica. 1954. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1957). The Philippines since pre-Spanish times.-v. 2. The Philippines since the British invasion. Volume 1 of Philippine Political and Cultural History (revised ed.). Philippine Education Company. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1979). The Pageant of Philippine History: Political, Economic, and Socio-cultural, Volume 1. Philippine Education Company. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Philippines (Republic). Office of Cultural Affairs (1965). The Philippines: a Handbook of Information. Contributor National Economic Council (Philippines) (revised ed.). Republic of the Philippines, Department of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Philippine Chinese Historical Association (1975). The Annals of Philippine Chinese Historical Association, Volumes 5-8 (revised ed.). Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- IAHA Conference (1962). Biennial Conference Proceedings, Issue 1. Philippine Historical Association. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- The Philippines: A Handbook of Information. Contributor Philippine Information Agency. Philippine Information Agency. 1955. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- University of Manila Journal of East Asiatic Studies, Volume 7. Contributors Manila (Philippines) University, University of Manila (revised ed.). University of Manila. 1959. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Unitas, Volume 30, Issues 1-2. Contributor University of Santo Tomás. University of Santo Tomás. 1957. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- The Researcher, Volume 2, Issue 2. Contributors University of Pangasinan, Dagupan Colleges. Dagupan Colleges. 1970. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Philippine Social Sciences and Humanities Review, Volumes 24–25. Contributor University of the Philippines. College of Liberal Arts. 1959. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Philippine Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews, Volume 24, Issues 1–2. Contributors Philippine Academy of Social Sciences, Manila, University of the Philippines. College of Liberal Arts. College of Liberal Arts, University of the Philippines. 1959. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Studies in Public Administration, Issue 4. Contributor University of the Philippines. Institute of Public Administration. Institute of Public Administration, University of the Philippines. 1957. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Proceedings [of The] Second Biennial Conference, Held at Taiwan Provincial Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Republic of China, October 6–9, 1962. Tʻai-pei. 1963. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Yearbook. 1965. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Philippine Almanac & Handbook of Facts. 1977. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- International Institute of Differing Civilizations (1961). Compte rendu. Contributor International Colonial Institute. The Institute. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry, Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle, University of Washington Press, 2002. ISBN 0-295-98124-5. Partial text on Google Books.

- Louise Levathes, When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433, Oxford University Press, 1997, trade paperback, ISBN 0-19-511207-5

- 《明實錄太宗實錄》 in the Veritable Records of the Ming

Yongle Emperor Born: 2 May 1360 Died: 12 August 1424 | ||

| Chinese royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| New creation | Prince of Yan 1370 – 1402 |

Merged in the Crown |

| Regnal titles | ||

| Preceded by The Jianwen Emperor |

Emperor of China Ming Dynasty 1402 – 1424 |

Succeeded by The Hongxi Emperor |