Dialect

The term dialect (from Latin dialectus, dialectos, from the Ancient Greek word διάλεκτος, diálektos, "discourse", from διά, diá, "through" and λέγω, légō, "I speak") is used in two distinct ways to refer to two different types of linguistic phenomena:

- One usage refers to a variety of a language that is a characteristic of a particular group of the language's speakers.[1] Under this definition, the dialects or varieties of a particular language are closely related and, despite their differences, are most often largely mutually intelligible, especially if close to one another on the dialect continuum. The term is applied most often to regional speech patterns, but a dialect may also be defined by other factors, such as social class or ethnicity.[2] A dialect that is associated with a particular social class can be termed a sociolect, a dialect that is associated with a particular ethnic group can be termed as ethnolect, and a regional dialect may be termed a regiolect.[3] According to this definition, any variety of a given language constitutes "a dialect", including any standard varieties. In this case, the distinction between the "standard language" (i.e. the "standard" dialect of a particular language) and the "nonstandard" dialects of the same language is often arbitrary and based on social, political, cultural, or historical considerations.[4][5][6] In a similar way, the definitions of the terms "language" and "dialect" may overlap and are often subject to debate, with the differentiation between the two classifications often grounded in arbitrary and/or sociopolitical motives.[7]

- The other usage of the term "dialect", often deployed in colloquial settings, refers (often somewhat pejoratively) to a language that is socially subordinated to a regional or national standard language, often historically cognate or genetically related to the standard language, but not actually derived from the standard language. In other words, it is not an actual variety of the "standard language" or dominant language, but rather a separate, independently evolved but often distantly related language.[8] In this sense, unlike in the first usage, the standard language would not itself be considered a "dialect", as it is the dominant language in a particular state or region, whether in terms of linguistic prestige, social or political status, official status, predominance or prevalence, or all of the above. Meanwhile, under this usage, the "dialects" subordinate to the standard language are generally not variations on the standard language but rather separate (but often loosely related) languages in and of themselves. Thus, these "dialects" are not dialects or varieties of a particular language in the same sense as in the first usage; though they may share roots in the same family or subfamily as the standard language and may even, to varying degrees, share some mutual intelligibility with the standard language, they often did not evolve closely with the standard language or within the same linguistic subgroup or speech community as the standard language and instead may better fit the criteria of a separate language.

For example, most of the various regional Romance languages of Italy, often colloquially referred to as Italian "dialects", are, in fact, not actually derived from modern standard Italian, but rather evolved from Vulgar Latin separately and individually from one another and independently of standard Italian, long prior to the diffusion of a national standardized language throughout what is now Italy. These various Latin-derived regional languages are, therefore, in a linguistic sense, not truly "dialects" or varieties of the standard Italian language, but are instead better defined as their own separate languages. Conversely, with the spread of standard Italian throughout Italy in the 20th century, regional versions or varieties of standard Italian have developed, generally as a mix of national standard Italian with a substratum of local regional languages and local accents. While "dialect" levelling has increased the number of standard Italian speakers and decreased the number of speakers of other languages native to Italy, Italians in different regions have developed variations of standard Italian particular to their region. These variations on standard Italian, known as regional Italian, would thus more appropriately be called "dialects" in accordance with the first linguistic definition of "dialect", as they are in fact derived partially or mostly from standard Italian.[9][8][10]

A dialect is distinguished by its vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation (phonology, including prosody). Where a distinction can be made only in terms of pronunciation (including prosody, or just prosody itself), the term accent may be preferred over dialect. Other types of speech varieties include jargons, which are characterized by differences in lexicon (vocabulary); slang; patois; pidgins; and argots. The particular speech patterns used by an individual are termed an idiolect.

Standard and non-standard dialect

A standard dialect (also known as a standardized dialect or "standard language") is a dialect that is supported by institutions. Such institutional support may include government recognition or designation; presentation as being the "correct" form of a language in schools; published grammars, dictionaries, and textbooks that set forth a correct spoken and written form; and an extensive formal literature that employs that dialect (prose, poetry, non-fiction, etc.). There may be multiple standard dialects associated with a single language. For example, Standard American English, Standard British English, Standard Canadian English, Standard Indian English, Standard Australian English, and Standard Philippine English may all be said to be standard dialects of the English language.

A nonstandard dialect, like a standard dialect, has a complete vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, but is usually not the beneficiary of institutional support. Examples of a nonstandard English dialect are Southern American English, Western Australian English, New York English, New England English, Mid-Atlantic American or Philadelphia / Baltimore English, Scouse, Brummie, Cockney, and Tyke. The Dialect Test was designed by Joseph Wright to compare different English dialects with each other.

Dialect or language

There is no universally accepted criterion for distinguishing two different languages from two dialects (i.e. varieties) of the same language.[11] A number of rough measures exist, sometimes leading to contradictory results. The distinction is therefore subjective and depends upon the user's frame of reference. For example, there has been discussion about whether or not the Limón Creole English should be considered "a kind" of English or a different language. This creole is spoken in the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica (Central America) by descendants of Jamaican people. The position that Costa Rican linguists support depends upon which University they represent.

The most common, and most purely linguistic, criterion is that of mutual intelligibility: two varieties are said to be dialects of the same language if being a speaker of one variety confers sufficient knowledge to understand and be understood by a speaker of the other; otherwise, they are said to be different languages. However, this definition becomes problematic in the case of dialect continua, in which it may be the case that dialect B is mutually intelligible with both dialect A and dialect C but dialects A and C are not mutually intelligible with each other. In this case, the criterion of mutual intelligibility makes it impossible to decide whether A and C are dialects of the same language or not. The mutual intelligibility criterion also flounders in cases in which a speaker of dialect X can understand a speaker of dialect Y, but not vice versa.

Sociolinguistic definitions

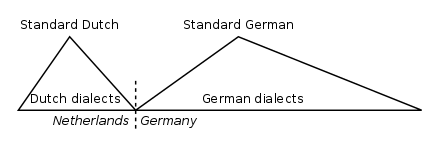

Another occasionally used criterion for discriminating dialects from languages is the sociolinguistic notion of linguistic authority. According to this definition, two varieties are considered dialects of the same language if (under at least some circumstances) they would defer to the same authority regarding some questions about their language. For instance, to learn the name of a new invention, or an obscure foreign species of plant, speakers of Westphalian and East Franconian German might each consult a German dictionary or ask a German-speaking expert in the subject. Thus these varieties are said to be dependent on, or heteronomous with respect to, Standard German, which is said to be autonomous. In contrast, speakers in the Netherlands of Low Saxon varieties similar to Westphalian would instead consult a dictionary of Standard Dutch. Similarly, although Yiddish is classified by linguists as a language in the Middle High German group of languages, a Yiddish speaker would consult a different dictionary in such a case.

Within this framework, W. A. Stewart defined a language as an autonomous variety together with all the varieties that are heteronomous with respect to it, noting that an essentially equivalent definition had been stated by Charles A. Ferguson and John J. Gumperz in 1960.[13][14] Similarly, a heteronomous variety may be considered a dialect of a language defined in this way.[13] In these terms, Danish and Norwegian, though mutually intelligible to a large degree, are considered separate languages.[15] In the framework of Heinz Kloss, these are described as languages by ausbau (development) rather than by abstand (separation).[16]

Dialect and language clusters

In other situations, a closely related group of varieties possess considerable (though incomplete) mutual intelligibility, but none dominates the others. To describe this situation, the editors of the Handbook of African Languages introduced the term dialect cluster. Dialect clusters were treated as classificatory units at the same level as languages.[17] A similar situation, but with a greater degree of mutual unintelligibility, has been termed a language cluster.[18]

Political factors

In many societies, however, a particular dialect, often the sociolect of the elite class, comes to be identified as the "standard" or "proper" version of a language by those seeking to make a social distinction and is contrasted with other varieties. As a result of this, in some contexts, the term "dialect" refers specifically to varieties with low social status. In this secondary sense of "dialect", language varieties are often called dialects rather than languages:

- if they have no standard or codified form,

- if they are rarely or never used in writing (outside reported speech),

- if the speakers of the given language do not have a state of their own,

- if they lack prestige with respect to some other, often standardised, variety.

The status of "language" is not solely determined by linguistic criteria, but it is also the result of a historical and political development. Romansh came to be a written language, and therefore it is recognized as a language, even though it is very close to the Lombardic alpine dialects. An opposite example is the case of Chinese, whose variations such as Mandarin and Cantonese are often called dialects and not languages in China, despite their mutual unintelligibility.

Modern nationalism, as developed especially since the French Revolution, has made the distinction between "language" and "dialect" an issue of great political importance. A group speaking a separate "language" is often seen as having a greater claim to being a separate "people", and thus to be more deserving of its own independent state, while a group speaking a "dialect" tends to be seen not as "a people" in its own right, but as a sub-group, part of a bigger people, which must content itself with regional autonomy. The distinction between language and dialect is thus inevitably made at least as much on a political basis as on a linguistic one, and can lead to great political controversy or even armed conflict.

The Yiddish linguist Max Weinreich published the expression, A shprakh iz a dialekt mit an armey un flot ("אַ שפּראַך איז אַ דיאַלעקט מיט אַן אַרמײ און פֿלאָט": "A language is a dialect with an army and navy") in YIVO Bleter 25.1, 1945, p. 13. The significance of the political factors in any attempt at answering the question "what is a language?" is great enough to cast doubt on whether any strictly linguistic definition, without a socio-cultural approach, is possible. This is illustrated by the frequency with which the army-navy aphorism is cited.

Terminology

By the definition most commonly used by linguists, any linguistic variety can be considered a "dialect" of some language—"everybody speaks a dialect". According to that interpretation, the criteria above merely serve to distinguish whether two varieties are dialects of the same language or dialects of different languages.

The terms "language" and "dialect" are not necessarily mutually exclusive, although it is often perceived to be. Thus there is nothing contradictory in the statement "the language of the Pennsylvania Dutch is a dialect of German".

There are various terms that linguists may use to avoid taking a position on whether the speech of a community is an independent language in its own right or a dialect of another language. Perhaps the most common is "variety";[19] "lect" is another. A more general term is "languoid", which does not distinguish between dialects, languages, and groups of languages, whether genealogically related or not.[20]

Examples

German

When talking about the German language, the term German dialects is only used for the traditional regional varieties. That allows them to be distinguished from the regional varieties of modern standard German.

The German dialects show a wide spectrum of variation. Some of them are not mutually intelligible. German dialectology traditionally names the major dialect groups after Germanic tribes from which they were assumed to have descended.[21]

The extent to which the dialects are spoken varies according to a number of factors: In Northern Germany, dialects are less common than in the South. In cities, dialects are less common than in the countryside. In a public environment, dialects are less common than in a familiar environment.

The situation in Switzerland and Liechtenstein is different from the rest of the German-speaking countries. The Swiss German dialects are the default everyday language in virtually every situation, whereas standard German is only spoken in education, partially in media, and with foreigners not possessing knowledge of Swiss German. Most Swiss German speakers perceive standard German to be a foreign language.

The Low German varieties spoken in Germany are often counted among the German dialects. This reflects the modern situation where they are roofed by standard German. This is different from the situation in the Middle Ages when Low German had strong tendencies towards an ausbau language.

The Frisian languages spoken in Germany are excluded from the German dialects.

Italian

Italy is home to a vast array of native regional minority languages, most of which are Romance-based and have their own local variants. These regional languages are often referred to colloquially or in non-linguistic circles as Italian "dialects", or dialetti (standard Italian for "dialects"). However, the majority of the regional languages in Italy are in fact not actually "dialects" of standard Italian in the strict linguistic sense, as they are not derived from modern standard Italian but instead evolved locally from Vulgar Latin independent of standard Italian, with little to no influence from what is now known as "standard Italian." They are therefore better classified as individual languages rather than "dialects."

In addition to having evolved, for the most part, separately from one another and with distinct individual histories, the Latin-based regional Romance languages of Italy are also better classified as separate languages rather than true "dialects" due to the often high degree in which they lack mutual intelligibility. Though mostly mutually unintelligible, the exact degree to which the regional Italian languages are mutually unintelligible varies, often correlating with geographical distance or geographical barriers between the languages, with some regional Italian languages that are closer in geographical proximity to each other or closer to each other on the dialect continuum being more or less mutually intelligible. For instance, a speaker of purely Eastern Lombard, a language in Northern Italy's Lombardy region that includes the Bergamasque dialect, would have severely limited mutual intelligibility with a purely standard Italian speaker and would be nearly completely unintelligible to a speaker of a pure Sicilian language variant. Due to Eastern Lombard's status as a Gallo-Italic language, an Eastern Lombard speaker may, in fact, have more mutual intelligibility with a Occitan, Catalan, or French speaker than with a standard Italian or Sicilian language speaker. Meanwhile, a Sicilian language speaker would have a greater degree of mutual intelligibility with a speaker of the more closely related Neapolitan language, but far less mutual intelligibility with a person speaking Sicilian Gallo-Italic, a language that developed in isolated Lombard emigrant communities on the same island as the Sicilian language.

Modern standard Italian itself is heavily based on the Latin-derived Florentine Tuscan language. The Tuscan-based language that would eventually become modern standard Italian had been used in poetry and literature since at least the 12th century, and it first spread throughout Italy among the educated upper class through the works of authors such as Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli, and Petrarch. Dante's Florentine-Tuscan literary Italian thus slowly became the language of the literate and upper class in Italy, and it spread throughout the peninsula as the lingua franca among the Italian educated class as well as Italian traveling merchants. The economic prowess and cultural and artistic importance of Tuscany in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance further encouraged the diffusion of the Florentine-Tuscan Italian throughout Italy and among the educated and powerful, though local and regional languages remained the main languages of the common people.

During the Risorgimento, proponents of Italian republicanism and Italian nationalism, such as Alessandro Manzoni, stressed the importance of establishing a uniform national language in order to better create an Italian national identity. With the unification of Italy in the 1860s, standard Italian became the official national language of the new Italian state, while the various unofficial regional languages of Italy gradually became regarded as subordinate "dialects" to Italian, increasingly associated negatively with lack of education or provincialism. However, at the time of the Italian Unification, standard Italian still existed mainly as a literary language, and only 2.5% of Italy's population could speak standard Italian.[22]

In the early 20th century, the vast conscription of Italian men from all throughout Italy during World War I is credited with facilitating the diffusion of standard Italian among less educated Italian men, as these men from various regions with various regional languages were forced to communicate with each other in a common tongue while serving in the Italian military. With the eventual spread of the radio and television throughout Italy and the establishment of public education, Italians from all regions were increasingly exposed to standard Italian, while literacy rates among all social classes improved. Today, the majority of Italians are able to speak standard Italian, though many Italians still speak their regional language regularly or as their primary day-to-day language, especially at home with family or when communicating with Italians from the same town or region. However, to some Italians, speaking a regional language, especially in a formal setting or outside of one's region, may carry a stigma or negative connotations associated with being lower class, uneducated, boorish, or overly informal.

Italians in different regions today may also speak regional varieties of standard Italian, or regional Italian dialects, which, unlike the majority of languages of Italy, are actually dialects of standard Italian rather than separate languages. A regional Italian dialect is generally standard Italian that has been heavily influenced or mixed with local or regional native languages and accents.

The languages of Italy are primarily Latin-based Romance languages, with the most widely spoken languages falling within the Italo-Dalmatian language family. This wide category includes:

- Standard Italian and Tuscan;

- the various related Central Italian dialects, such as Romanesco in Rome;

- the Neapolitan group (also known as "Southern Italian"), which encompasses not only Naples' and Campania's speech but also a variety of related neighboring varieties like the Irpinian dialect, Abruzzese and Southern Marchegiano, Molisan, Northern Calabrian or Cosentino, and the Bari dialect;

- the Sicilian group, including Salentino and Calabrian.

The Cilentan dialect of Salerno is considered significantly influenced by both the Neapolitan and Sicilian language groups.

The Sardinian language is considered to be its own Romance language family, separate not only from Italian and the wider Italo-Dalmatian family but basal to all other romance families. It is often subdivided into the Campidanese and Logudorese dialects. The Corsican-related Gallurese and Sassarese which are also spoken in Sardinia, on the other hand, are often considered closely related to or derived from Tuscan and are therefore fully part of the Italo-Dalmatian languages. Furthermore, the Gallo-Romance language of Ligurian and the Catalan Algherese dialect are also spoken in Sardinia, respectively in Carloforte/Calasetta and Alghero.

Aside from the more common Italo-Dalmatian Romance languages in Italy, other native languages in Italy include:

- a variety of Gallo-Italic languages, Gallo-Rhaetian languages, Rhaeto-Romance languages, and Ibero-Romance languages (such as Emilian-Romagnol, Ligurian, Friulian, the Lombard languages, Sicilian Gallo-Italic, Algherese, the Vivaro-Alpine dialect, Ladin, etc.);

- Germanic languages, such as the Cimbrian languages, Southern Bavarian, Walser German and the Mòcheno language;

- the Albanian Arbëresh language;

- the Hellenic Griko language and Calabrian Greek;

- the Serbo-Croatian Slavomolisano dialect; and

- various Slovene languages, including the Gail Valley dialect and Istrian dialect.

The Balkans

The classification of speech varieties as dialects or languages and their relationship to other varieties of speech can be controversial and the verdicts inconsistent. English and Serbo-Croatian illustrate the point. English and Serbo-Croatian each have two major variants (British and American English, and Serbian and Croatian, respectively), along with numerous other varieties. For political reasons, analyzing these varieties as "languages" or "dialects" yields inconsistent results: British and American English, spoken by close political and military allies, are almost universally regarded as varieties of a single language, whereas the national standards of Serbia and Croatia, which are closer to each other than some local vernacular dialects of Serbo-Croatian are to themselves, differing to a similar extent as the formal varieties of English, are treated by some linguists from the region as distinct languages, largely because the two countries oscillate from being brotherly to being bitter enemies. (The Serbo-Croatian language article deals with this topic much more fully.)

Similar examples abound. Macedonian, although largely mutually intelligible with Bulgarian, certain dialects of Serbo-Croatian and to a lesser extent the rest of the South Slavic dialect continuum, is considered by Bulgarian linguists to be a Bulgarian dialect, in contrast with the contemporary international view and the view in the Republic of Macedonia, which regards it as a language in its own right. Nevertheless, before the establishment of a literary standard of Macedonian in 1944, in most sources in and out of Bulgaria before the Second World War, the southern Slavonic dialect continuum covering the area of today's Republic of Macedonia were referred to as Bulgarian dialects.

Lebanon

In Lebanon, a part of the Christian population considers "Lebanese" to be in some sense a distinct language from Arabic and not merely a dialect. During the civil war Christians often used Lebanese Arabic officially, and sporadically used the Latin script to write Lebanese, thus further distinguishing it from Arabic. All Lebanese laws are written in the standard literary form of Arabic, though parliamentary debate may be conducted in Lebanese Arabic.

North Africa

In Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, the Darijas (spoken North African languages) are sometimes considered more different from other Arabic dialects. Officially, North African countries prefer to give preference to the Literary Arabic and conduct much of their political and religious life in it (adherence to Islam), and refrain from declaring each country's specific variety to be a separate language, because Literary Arabic is the liturgical language of Islam and the language of the Islamic sacred book, the Qur'an. Although, especially since the 1960s, the Darijas are occupying an increasing use and influence in the cultural life of these countries. Examples of cultural elements where Darijas' use became dominant include: theatre, film, music, television, advertisement, social media, folk-tale books and companies' names.

Ukraine

The Modern Ukrainian language has been in common use since the late 17th century, associated with the establishment of the Cossack Hetmanate. In the 19th century, the Tsarist Government of the Russian Empire claimed that Ukrainian was merely a dialect of Russian and not a language on its own. According to these claims, the differences were few and caused by the conquest of western Ukraine by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. However, in reality the dialects in Ukraine were developing independently from the dialects in the modern Russia for several centuries, and as a result they differed substantially.

Following the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, the German Empire briefly gained control over Ukraine during World War I, but was eventually defeated by the Entente, with major involvement by the Ukrainian Bolsheviks. After Bolsheviks managed to conquer the rest of Ukraine from the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Whites, Ukraine became part of the USSR, whence a process of Ukrainization was begun, with encouragement from Moscow. However, in the late 1920s - early 1930s, the process started to reverse. Witnessing the Ukrainian cultural revival spurred by the ukrainization in the early 1290s, and fearing that it might lead to an independence movement, Moscow started to remove from power and in some cases physically eliminate the public proponents of ukrainization. The appointment of Pavel Postyshev as the secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine marked the end of ukrainization, and the opposite process of russification started. After World War II, citing Ukrainian collaboration with Nazi Germany in an attempt to gain independence as the reason, Moscow changed its policy towards repression of the Ukrainian language.

Today the boundaries of the Ukrainian language to the Russian language are still not drawn clearly, with an intermediate dialect between them, called Surzhyk, developing in Ukraine.

Moldova

There have been cases of a variety of speech being deliberately reclassified to serve political purposes. One example is Moldovan. In 1996, the Moldovan parliament, citing fears of "Romanian expansionism", rejected a proposal from President Mircea Snegur to change the name of the language to Romanian, and in 2003 a Moldovan–Romanian dictionary was published, purporting to show that the two countries speak different languages. Linguists of the Romanian Academy reacted by declaring that all the Moldovan words were also Romanian words; while in Moldova, the head of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova, Ion Bărbuţă, described the dictionary as a politically motivated "absurdity".

Greater China

Unlike languages that use alphabets to indicate their pronunciation, Chinese characters have developed from logograms that do not always give hints to their pronunciation. Although the written characters have remained relatively consistent for the last two thousand years, the pronunciation and grammar in different regions have developed to an extent that the varieties of the spoken language are often mutually unintelligible. As a series of migration to the south throughout the history, the regional languages of the south, including Gan, Xiang, Wu, Min, Yue and Hakka often show traces of Old Chinese or Middle Chinese. From the Ming dynasty onward, Beijing has been the capital of China and the dialect spoken in Beijing has had the most prestige among other varieties. With the founding of the Republic of China, Standard Mandarin was designated as the official language, based on the spoken language of Beijing. Since then, other spoken varieties are regarded as fangyan (regional speech). Cantonese is still the most commonly-used language in Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Macau and among some overseas Chinese communities, whereas Hokkien has been accepted in Taiwan as an important local language alongside Mandarin.

Interlingua

One language, Interlingua, was developed so that the languages of Western civilization would act as its dialects.[23] Drawing from such concepts as the international scientific vocabulary and Standard Average European, linguists developed a theory that the modern Western languages were actually dialects of a hidden or latent language. Researchers at the International Auxiliary Language Association extracted words and affixes that they considered to be part of Interlingua's vocabulary.[24] In theory, speakers of the Western languages would understand written or spoken Interlingua immediately, without prior study, since their own languages were its dialects.[23] This has often turned out to be true, especially, but not solely, for speakers of the Romance languages and educated speakers of English. Interlingua has also been found to assist in the learning of other languages. In one study, Swedish high school students learning Interlingua were able to translate passages from Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian that students of those languages found too difficult to understand.[25] It should be noted, however, that the vocabulary of Interlingua extends beyond the Western language families.[24]

Selected list of articles on dialects

See also

References

- ↑ Oxford English dictionary.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Online dictionary.

- ↑ Wolfram, Walt and Schilling, Natalie. 2016. American English: Dialects and Variation. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, p. 184.

- ↑ Chao, Yuen Ren (1968). Language and Symbolic Systems. CUP archive.

- ↑ Lyons, John (1981). Language and Linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Johnson, David. How Myths about Language Affect Education: What Every Teacher Should Know.

- ↑ McWorther, John (Jan 19, 2016). "What's a Language, Anyway?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- 1 2 Maiden, Martin; Parry, Mair (1997). The Dialects of Italy. Routledge. p. 2.

- ↑ Loporcaro, Michele (2009). Profilo linguistico dei dialetti italiani (in Italian). Bari: Laterza. ; Marcato, Carla (2007). Dialetto, dialetti e italiano (in Italian). Bologna: Il Mulino. ; Posner, Rebecca (1996). The Romance languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Repetti, Lori (2000). Phonological Theory and the Dialects of Italy. John Benjamins Publishing. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Cysouw, Michael; Good, Jeff. (2013). "Languoid, Doculect, and Glossonym: Formalizing the Notion 'Language'." Language Documentation and Conservation. 7. 331–359. hdl:10125/4606.

- ↑ Chambers, J. K.; Trudgill, Peter (1998). Dialectology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-521-59646-6.

- 1 2 Stewart, William A. (1968). "A sociolinguistic typology for describing national multilingualism". In Fishman, Joshua A. Readings in the Sociology of Language. De Gruyter. pp. 531–545. doi:10.1515/9783110805376.531. ISBN 978-3-11-080537-6. p. 535.

- ↑ Ferguson, Charles A.; Gumperz, John J. (1960). "Introduction". In Ferguson, Charles A.; Gumperz, John J. Linguistic Diversity in South Asia: Studies in Regional, Social, and Functional Variation. Indiana University, Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics. pp. 1–18. p. 5.

- ↑ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 11

- ↑ Kloss, Heinz (1967). "'Abstand languages' and 'ausbau languages'". Anthropological Linguistics. 9 (7): 29–41. JSTOR 30029461.

- ↑ Handbook Sub-committee Committee of the International African Institute. (1946). "A Handbook of African Languages". Africa. 16 (3): 156–159. JSTOR 1156320.

- ↑ Hansford, Keir; Bendor-Samuel, John; Stanford, Ron (1976). "A provisional language map of Nigeria". Savanna. 5 (2): 115–124. p. 118.

- ↑ Finegan, Edward (2007). Language: Its Structure and Use (5th ed.). Boston, MA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-4130-3055-6.

- ↑ "Languoid" at Glottopedia.com

- ↑ Danvas, Kegesa (2016). "From dialect to variation space". Cutewriters. Cutewriters Inc. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- 1 2 Morris, Alice Vanderbilt, General report Archived 2006-08-14 at the Wayback Machine.. New York: International Auxiliary Language Association, 1945.

- 1 2 Gode, Alexander, Interlingua-English Dictionary. New York: Storm Publishers, 1951.

- ↑ Gopsill, F. P., International languages: A matter for Interlingua. Sheffield: British Interlingua Society, 1990.

External links

- Sounds Familiar? – Listen to regional accents and dialects of the UK on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website

- International Dialects of English Archive Since 1997

- whoohoo.co.uk British Dialect Translator

- thedialectdictionary.com – Compilation of Dialects from around the globe

- A site for announcements and downloading the SEAL System