Geography of Japan

| |

| Continent | Asia |

|---|---|

| Region | East Asia, North East Asia |

| Coordinates | 36°N 138°E / 36°N 138°E |

| Area | Ranked 61st |

| • Total | 377,973.89[1] km2 (145,936.53 sq mi) |

| • Land | 87.93099% |

| • Water | 12.06901% |

| Coastline | 29,751 km (18,486 mi) |

| Borders | No land borders |

| Highest point |

Mount Fuji 3,776 m (12,388 ft)[2] |

| Lowest point |

Hachirōgata −4 m (−13 ft)[2] |

| Longest river |

Shinano River 367 km (228 mi)[3] |

| Largest lake |

Lake Biwa 671 km2 (259 sq mi)[4] |

| Climate | varied; warm subtropical in south to cool continental in north[2] |

| Terrain | mostly rugged and mountainous[2] |

| Natural Resources | Marine resources. Small deposits of coal, oil, iron and minerals.[2] |

| Natural Hazards | volcanoes, tsunamis, earthquakes and typhoons[2] |

| Environmental Issues | air pollution; acidification of lakes and reservoirs; overfishing; deforestation[2] |

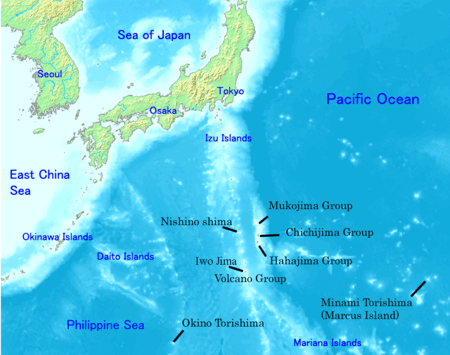

Japan is an island nation comprising a stratovolcanic archipelago over 3,000 km (1,900 mi) along East Asia's Pacific coast.[5] It consists of 6,852 islands.[6] The main islands are Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku and Hokkaido. The Ryukyu Islands and Nanpō Islands are south of the main islands. The territory extends 377,973.89 km2 (145,936.53 sq mi).[1] It is the largest island country in East Asia and fourth largest island country in the world. Japan has the sixth longest coastline 29,751 km (18,486 mi) and the eight largest Exclusive Economic Zone of 4,470,000 km2 (1,730,000 sq mi) in the world.[7]

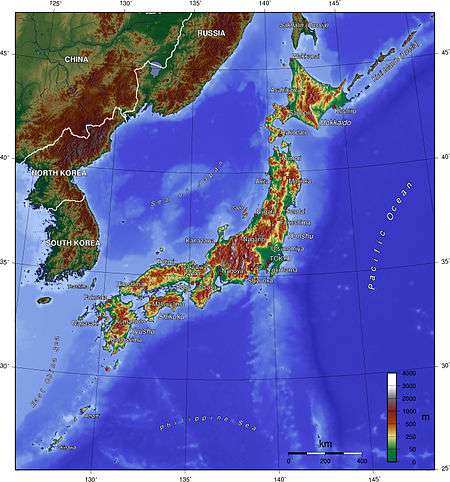

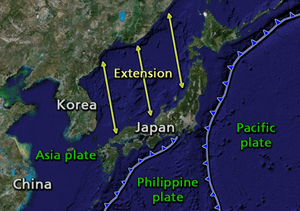

The terrain is mostly rugged and mountainous with 66% forest.[8] The population is clustered in urban areas on the coast, plains and valleys.[9] Japan is located in the northwestern Ring of Fire on multiple tectonic plates.[10] East of the Japanese archipelago are three oceanic trenches. The Japan Trench is created as the oceanic Pacific Plate subducts beneath the continental Okhotsk Plate.[11] The continuous subduction process causes frequent earthquakes, tsunami and stratovolcanoes.[12] The islands are also affected by typhoons. The subduction plates have pulled the Japanese archipelago eastward, created the Sea of Japan and separated it from the Asian continent by back-arc spreading 15 million years ago.[10]

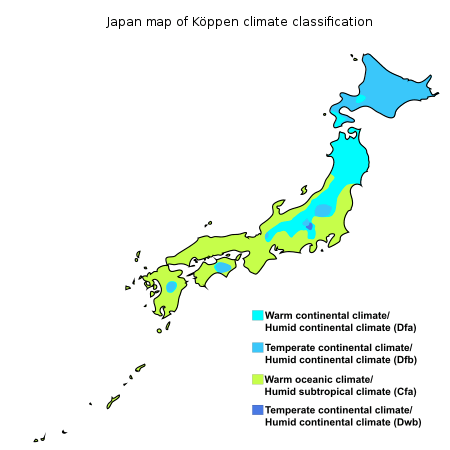

The climate of the Japanese archipelago varies from humid continental in the north (Hokkaido) to humid subtropical and tropical rainforest in the south (Okinawa Prefecture). These differences in climate and landscape have allowed the development of a diverse flora and fauna, with some rare endemic species, especially in the Ogasawara Islands.

Japan extends from 20° to 45° north longitude (Okinotorishima to Benten-jima) and from 122° to 153° east latitude (Yonaguni to Minami Torishima).[13] Japan is surrounded by sea. To the north the Sea of Okhotsk separates it from the Russian Far East, to the west the Sea of Japan separates it from the Korean Peninsula, to the southwest the East China Sea separates the Ryukyu Islands from China and Taiwan, to the east is the Pacific Ocean.

Overview

The Japanese archipelago is over 3,000 km (1,900 mi) long in a north-to-southwardly direction from the Sea of Okhotsk to the Philippine Sea in the Pacific Ocean.[5] The major islands, sometimes called the "Home Islands", are (from east to west) Hokkaido, Honshu (the "mainland"), Shikoku and Kyushu. There are 6,852 islands in total,[6] including the Nansei Islands, the Nanpō Islands and islets, with 430 islands being inhabited and others uninhabited. In total, as of 2018, Japan's territory is 377,973.89 km2 (145,936.53 sq mi), of which 364,543.89 km2 (140,751.18 sq mi) is land and 13,430 km2 (5,190 sq mi) water.[1] Japan has the sixth longest coastline in the world (29,751 km (18,486 mi)). It is the largest island country in East Asia and fourth largest island country in the world. There are a wide range of climatic zones and ecosystems.

Due to Japan's many far-flung outlying islands and long coastline, the country has extensive marine resources. The Exclusive Economic Zone of Japan covers 4,470,000 km2 (1,730,000 sq mi) and is the eighth largest in the world. It is more than 11 times the land area of the country.[7]

Japan has a population of 126,672,000 in 2016.[14] It is the tenth most populous country in the world and second most populous island country. 81% of the population lives on Honshu, 10% on Kyushu, 4.2% on Hokkaido, 3% on Shikoku, 1.1% in Okinawa Prefecture and 0.7% on other Japanese islands such as the Nanpō Islands.

Area

- total: 377,973.89 km2 (145,936.53 sq mi) [1]

- land: 364,543.89 km2 (140,751.18 sq mi)

- water: 13,430 km2 (5,190 sq mi)

- notes: Includes the Bonin Islands, Daitō Islands, Minami-Tori-shima, Okinotorishima, the Ryukyu Islands, and the Volcano Islands. This includes the Senkaku Islands which are owned by Japan and disputed by the PRC. It excludes the disputed Northern Territories (Kuril islands) and Liancourt Rocks (Japanese:Takeshima, Korean:Dokdo).

Location: Japan is a long island chain between the Sea of Okhotsk, the Sea of Japan and the Philippine Sea. It is in the Pacific Ocean, East Asia and North East Asia. Japan is east of Siberia, the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan.

Map references: Asia, East Asia, North East Asia, Pacific Ocean

Terrain: mostly rugged and mountainous with about 70% mountainous land (comparable to Norway).

Land boundaries: the ocean, no land borders.

Coastline: 29,751 km (18,486 mi)

Population: 126,672,000 (2016)

Maritime territory

- Territorial sea: 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi); between 3 and 12 nmi (5.6 and 22.2 km; 3.5 and 13.8 mi) in the international straits—La Pérouse (or Sōya Strait), Tsugaru Strait, Osumi, and Eastern and Western Channels of the Korea or Tsushima Strait.

- Exclusive economic zone of Japan: 4,470,000 km2 (1,730,000 sq mi). It stretches from the baseline out to 200 nautical miles (nmi) from its coast.

- Contiguous zone: 24 nmi (44.4 km; 27.6 mi)

Climate: varies from humid continental climate in the north (Hokkaido) to humid subtropical and tropical rainforest climate in the south (Okinawa Prefecture) of the Japanese archipelago.

Natural resources: small deposits of coal, oil, iron and minerals. There is a major fishing industry and untapped marine resources in the Exclusive Economic Zone of Japan.

Land use

- arable land: 11.65%

- permanent crops: 0.83%

- other: 87.52% (2012)

Irrigated land: 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) (2010)

Total renewable water resources: 430 km3 (100 cu mi) (2011)

Freshwater withdrawal (domestic/industrial/agricultural):

- total: 90.04 km3 (21.60 cu mi) per year (20%/18%/62%)

- per capita: 714.3 m3 (25,230 cu ft) per year (2007)

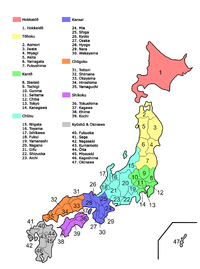

Regions

Japan is informally divided into eight regions from north to south:[15]

- Hokkaidō

- Tōhoku region

- Kantō region

- Chūbu region

- Kansai (or Kinki) region

- Chūgoku region

- Shikoku

- Kyūshū

Each contains several prefectures, except the Hokkaido region, which covers only Hokkaido Prefecture.

The regions are not official administrative units, but have been traditionally used as the regional division of Japan in a number of contexts. For example, maps and geography textbooks divide Japan into the eight regions, weather reports usually give the weather by region, and many businesses and institutions use their home region as part of their name (Kinki Nippon Railway, Chūgoku Bank, Tohoku University, etc.). While Japan has eight High Courts, their jurisdictions do not correspond with the eight regions.

Composition, topography and geography

About 73% of Japan is mountainous, with a mountain range running through each of the main islands. Japan's highest mountain is Mount Fuji, with an elevation of 3,776 m (12,388 ft). Japan's forest cover rate is 68.55% since the mountains are heavily forested. The only other developed nations with such a high forest cover percentage are Finland and Sweden.[8]

Since there is little level ground, many hills and mountainsides at lower elevations around towns and cities are often cultivated. As Japan is situated in a volcanic zone along the Pacific deeps, frequent low-intensity earth tremors and occasional volcanic activity are felt throughout the islands. Destructive earthquakes occur several times a century. Hot springs are numerous and have been exploited as an economic capital by the leisure industry.

The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan measures Japan's territory annually in order to continuously grasp the state of the national land. As of January 31, 2018 (Heisei 30) Japan's territory is 377,973.89 square kilometres (145,936.53 sq mi). It increased in area due to the volcanic eruption activity of Nishinoshima (西之島) and the natural expansion of the island.[1]

According to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, this is the “Trends and Actual Condition of Land Use in Japan” in 2002 (Heisei 14). Japan's territory was 377,900 km2 (145,900 sq mi) in 2002.<ref="mlit-2011">"土地総合情報ライブラリー 平成16年土地の動向に関する年次報告 第2章 土地に関する動向" (PDF) (in Japanese). 国土交通省. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-01-20. Retrieved 2007-02-17. </ref>

| Forest | Agricultural land | Residential area | Water surface, rivers, waterways | Roads | Wilderness | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66.4% | 12.8% | 4.8% | 3.6% | 3.4% | 0.7% | 8.3% |

| 251,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi) | 48,400 km2 (18,700 sq mi) | 18,100 km2 (7,000 sq mi) | 13,500 km2 (5,200 sq mi) | 13,000 km2 (5,000 sq mi) | 2,600 km2 (1,000 sq mi) | 31,300 km2 (12,100 sq mi) |

Mountains and volcanoes

{{Citation needed|reason=Mountains and volcanoes paragraphs need citations|date=October 2018}}

The mountainous islands of the Japanese archipelago form a crescent off the eastern coast of Asia. They are separated from the mainland by the Sea of Japan, which historically served as a protective barrier. The country consists of four major islands: Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu; with more than 6,500 adjacent smaller islands and islets ("island" defined as land more than 100 m in circumference),[16] including the Izu Islands and Ogasawara Islands in the Nanpō Islands, and the Satsunan Islands, Okinawa Islands, and Sakishima Islands of the Ryukyu Islands.

The national territory also includes the Volcano Islands (Kazan Retto) such as Iwo Jima, located some 1,200 kilometers south of mainland Tokyo. A territorial dispute with Russia, dating from the end of World War II, over the two southernmost of the Kuril Islands, Etorofu and Kunashiri, and the smaller Shikotan Island and Habomai Islands northeast of Hokkaido remains a sensitive spot in Japanese–Russian relations (as of 2005). Excluding disputed territory, the archipelago covers about 378,000 square kilometers. No point in Japan is more than 150 kilometers from the sea.

The four major islands are separated by narrow straits and form a natural entity. The Ryukyu Islands curve 970 kilometers southward from Kyūshū.

The distance between Japan and the Korean Peninsula, the nearest point on the Asian continent, is about 200 kilometers at the Korea Strait. Japan has always been linked with the continent through trade routes, stretching in the north toward Siberia, in the west through the Tsushima Islands to the Korean Peninsula, and in the south to the ports on the south China coast.

The Japanese islands are the summits of mountain ridges uplifted near the outer edge of the continental shelf. About 73 percent of Japan's area is mountainous, and scattered plains and intermontane basins (in which the population is concentrated) cover only about 27 percent. A long chain of mountains runs down the middle of the archipelago, dividing it into two halves, the "face", fronting on the Pacific Ocean, and the "back", toward the Sea of Japan. On the Pacific side are steep mountains 1,500 to 3,000 meters high, with deep valleys and gorges.

Central Japan is marked by the convergence of the three mountain chains—the Hida, Kiso, and Akaishi mountains—that form the Japanese Alps (Nihon Arupusu), several of whose peaks are higher than 3,000 meters. The highest point in the Japanese Alps is Mount Kita at 3,193 meters. The highest point in the country is Mount Fuji (Fujisan, also erroneously called Fujiyama), a volcano dormant since 1707 that rises to 3,776 m (12,388 ft) above sea level in Shizuoka Prefecture. On the Sea of Japan side are plateaus and low mountain districts, with altitudes of 500 to 1,500 meters.

The populated plains or mountain basins are not extensive in area. The largest, the Kantō Plain, where Tokyo is situated, covers only 13,000 square kilometers. Other important plains are the Nōbi Plain surrounding Nagoya, the Kinai Plain in the Osaka–Kyoto area, the Sendai Plain around the city of Sendai in northeastern Honshū, and the Ishikari Plain on Hokkaidō. Many of these plains are along the coast, and their areas have been increased by land reclamation throughout recorded history.

Rivers, lakes and coasts

{{Citation needed|reason=Rivers, lakes and coasts paragraphs need citations|date=October 2018}}

Rivers are generally steep and swift, and few are suitable for navigation except in their lower reaches. Although most rivers are less than 300 kilometers in length, their rapid flow from the mountains provides a valuable, renewable resource: hydroelectric power generation. Japan's hydroelectric power potential has been exploited almost to capacity. Seasonal variations in flow have led to extensive development of flood control measures. Most of the rivers are relatively short. The longest, the Shinano River, which winds through Nagano Prefecture to Niigata Prefecture and flows into the Sea of Japan, is 367 km (228 mi) long. The largest freshwater lake is Lake Biwa 671 km2 (259 sq mi), northeast of Kyoto.

Extensive coastal shipping, especially around the Seto Inland Sea (Seto Naikai), compensates for the lack of navigable rivers. The Pacific coastline south of Tokyo is characterized by long, narrow, gradually shallowing inlets produced by sedimentation, which has created many natural harbors. The Pacific coastline north of Tokyo, the coast of Hokkaidō, and the Sea of Japan coast are generally unindented, with few natural harbors.

In November 2008, Japan filed a request to expand its claimed continental shelf.[17] In April 2012, the U.N. Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf recognized around 310,000 square kilometres (120,000 sq mi) of seabed around Okinotorishima, giving Japan priority over access to seabed resources in nearby areas. According to U.N. Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, the approved expansion is equal to about 82% of Japan's total land area.[17] The People's Republic of China and South Korea have opposed Japan's claim because they view Okinotorishima not as an island, but as a group of rocks.

Land Reclamation

The Japanese archipelago is mainly rugged and mountainous (73%) so the relatively small amount of habitable land has prompted significant terrain modification by humans over many centuries.

Approximately 0.5% of Japan’s total area is estimated to be reclaimed land (umetatechi). Some reclamation projects began as early as the 12th century. Land was reclaimed from the sea and from river deltas by building dikes and drainage, and rice paddies on terraces carved into mountainsides. Post-World War II was when the majority of land reclamation was undertaken. During Japan’s period of rapid economic growth following WWII, approximately 80 to 90% of the country’s tidal flatland was reclaimed. During Japan’s post-war economic miracle, various coastal areas across Japan undertook vast land reclamation projects to house maritime and industrial factories. This included Osaka Bay, Higashi Ogishima in Kawasaki and Nagasaki Airport. Kobe also changed shape with the construction of Port Island, Rokko Island and Kobe Airport. Late 20th and early 21st century projects include artificial islands such as Chubu Centrair International Airport in Ise Bay, Kansai International Airport in the middle of Osaka Bay, Yokohama Hakkeijima Sea Paradise and Wakayama Marina City.[18]

The village of Ogata in Akita, Japan, was established on land reclaimed from Lake Hachirogata (Japan's second largest lake at the time) starting in 1957. By 1977, the amount of land reclaimed totaled 172.03 square kilometres (66.42 sq mi).[19]

Examples of land reclamation in Japan:

- Kyogashima, Kobe - first man-made island built by Tairano Kyomori in 1173[18]

- The Hibiya Inlet, Tokyo - first large scale reclamation project started in 1592[18]

- Dejima, Nagasaki - built during Japan’s national isolation period in 1634. It was the sole trading post in Japan during the Sakoku period and was originally inhabited by Portuguese and then Dutch traders.[18]

- Tokyo Bay, Japan – 249 square kilometres (96 sq mi)[20] artificial island (2007).

- Kobe, Japan – 23 square kilometres (8.9 sq mi) (1995).[18]

Composition

Reclaimed land is made up of landfill from waste materials, dredged earth and sand, sediment, sluge, soil removed from construction sites. It is not just used to create man-made islands in harbors, but is also used to make embankments in inland areas.[18]

From November 8, 2011, Tokyo City began accepting rubble and waste from the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami region. This rubble was processed and, provided with imposed radiation levels, was used as landfill to create new man-made islands in Tokyo Bay. Local residents complained about possible contamination. Yamashita Park in Yokohama City was constructed using rubble from the great Kantō earthquake in 1923.[18]

Sometimes toxic substances are detected in a landfill. There is a high tendency for contamination to occur on man-made islands and reclaimed land that was once used by heavy industry that released chemicals into the ground. The biggest example of soil pollution is on the man-made island near Toyosu where Tokyo Gas once had a factory. Highly concentrated chemical substances were detected in the soil. Smaller cases of contamination can be found in various sites. This led to a rapid expansion of the soil-decontamination industry since 1998.[18]

Geology

Tectonic Plates

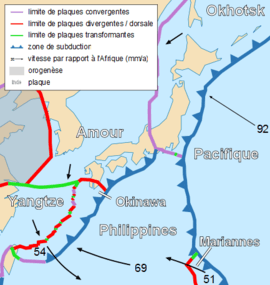

The islands of Japan were created by tectonic plate movements over several 100 millions of years from the mid-Silurian (443.8 Mya) to the Pleistocene (11,700 years ago).

- Tohoku (upper half of Honshu), Hokkaido, Kuril islands and Sakhalin (Karafuto) are located on the Okhotsk Plate. This is a minor tectonic plate bounded to the north by the North American Plate.[21][22] The Okhotsk Plate is bounded on the east by the Pacific Plate at the Kuril-Kamchatka Trench and the Japan Trench. It is bounded on the south by the Philippine Sea Plate at the Nankai Trough. On the west its bounded by the Eurasian Plate, and possibly on the southwest by the Amurian Plate. The north-eastern boundary is a left-lateral moving transform fault (Ulakhan Fault). [23]

- The southern half of Honshu, Shikoku and most of Kyushu are located on the Amurian Plate.

- The southern tip of Kyushu and the Ryukyu islands are located on the Okinawa Plate.

- The Nanpo Islands are on the Philippine Plate

The Pacific Plate and Philippine Plate are subduction plates. They are deeper than the Eurasian plate. The Philippine Sea Plate moves beneath the continental Amurian Plate and Okinawa Plate to the south. The Pacific Plate moves under the Okhotsk Plate to the north. These subduction plates have pulled Japan eastward and opened the Sea of Japan by back-arc spreading around 15 million years ago.[10] The Strait of Tartary and the Korea Strait opened much later. La Pérouse Strait formed about 60,000 to 11,000 years ago closing the path used by mammoths which had earlier moved to northern Hokkaido.[24]

The subduction zone is where the oceanic crust slides beneath the continental crust or other oceanic plates. This is because the oceanic plate's litosphere has a higher density.Subduction zones are sites that usually have a high rate of volcanism and earthquakes.[25] Additionally, subduction zones develop belts of deformation[26] The subduction zones on the east side of the Japanese archipelago cause frequent low intensity earth tremors. Major earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis occur several times per century. It is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire.[10] Northeastern Japan, north of Tanakura fault had high volcanic activity 14-17 million years before present.[27]

Oceanic Trenches

East of the Japanese archipelago are three oceanic trenches in the Pacific Ring of Fire.

- The Kuril–Kamchatka Trench is in the northwest Pacific Ocean. It lies off the southeast coast of Kamchatka and parallels the Kuril Island chain to meet the Japan Trench east of Hokkaido.[28]

- The Japan Trench extends 8,000 km (5,000 mi) from the Kuril Islands to the northern end of the Izu Islands, and is 8,046 m (5.000 mi) at its deepest.[29]

- The Izu-Ogasawara Trench is south of the Japan Trench in the western Pacific Ocean. It consists of the Izu Trench (at the north) and the Bonin Trench (at the south, west of the Ogasawara Plateau).[30] It stretches to the northern most section of the Mariana Trench.[31] The Izu-Ogasawara Trench is an extension of the Japan Trench. Here, the Pacific Plate is being subducted beneath the Philippine Sea Plate, creating the Izu Islands and Bonin Islands on the Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc system.[32]

The Japan Trench is created as the oceanic Pacific Plate subducts beneath the continental Okhotsk Plate. The subduction process causes bending of the down going plate, creating a deep trench. Continuing movement on the subduction zone associated with the Japan Trench is one of the main causes of tsunamis and earthquakes in northern Japan, including the megathrust 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. The rate of subduction associated with the Japan Trench has been recorded at about 7.9-9.2 cm/yr.[11]

Today the Japanese archipelago is considered a mature island arc and is the result of several generations of subducting plates. Approximately 15,000 km (9,300 mi) of oceanic floor has passed under the Japanese archipelago in the last 450 million years, with most being fully subducted.[10]

Composition

The Japanese islands are formed of the mentioned geological units parallel to the subduction front. The parts of islands facing the Pacific Ocean's Plate are typically younger and display a larger proportion of volcanic products, while island parts facing the Sea of Japan are mostly heavily faulted and folded sedimentary deposits. In north-west Japan are thick quaternary deposits. This makes determination of the geological history and composition especially difficult and it is not yet fully understood.[33]

Growing Archipelago

The Japanese Archipelago grows due to perpetual tectonic plate movements, earthquakes, stratovolcanoes and land reclamation in the Ring of Fire.

For example during the twentieth century several new volcanoes emerged, including Shōwa-shinzan on Hokkaido and Myōjin-shō off the Bayonnaise Rocks in the Pacific.[12] The 1914 Sakurajima eruption produced lava flows which connected the former island with the Osumi Peninsula in Kyushu.[34] It is the most active volcano in Japan.[35] The subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the Philippine Sea Plate created the Izu Islands and Bonin Islands on the Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc system.[32]

During the 2013 eruption southeast of Nishinoshima, a new unnamed volcanic island emerged from the sea.[36] Due to erosion and shifting sands, the new island merged with Nishinoshima and ceased to be a separate entity.[37][38] A 1911 survey determined the caldera was 107 m (351 ft) at its deepest.[39] This land formed naturally and increased the size of Japan.[1]

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami caused portions of northeastern Japan shifted by as much as 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) closer to North America,[40] making some sections of Japan's landmass wider than before.[41] Those areas of Japan closest to the epicenter experienced the largest shifts.[41] A 400-kilometre (250 mi) stretch of coastline dropped vertically by 0.6 metres (2 ft 0 in), allowing the tsunami to travel farther and faster onto land.[41] One early estimate suggested that the Pacific plate may have moved westward by up to 20 metres (66 ft),[42] and another early estimate put the amount of slippage at as much as 40 m (130 ft).[43] On 6 April the Japanese coast guard said that the quake shifted the seabed near the epicenter 24 metres (79 ft) and elevated the seabed off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture by 3 metres (9.8 ft).[44] A report by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, published in Science on 2 December 2011, concluded that the seabed in the area between the epicenter and the Japan Trench moved 50 metres (160 ft) east-southeast and rose about 7 metres (23 ft) as a result of the quake. The report also stated that the quake had caused several major landslides on the seabed in the affected area.[45]

Sea of Japan

History

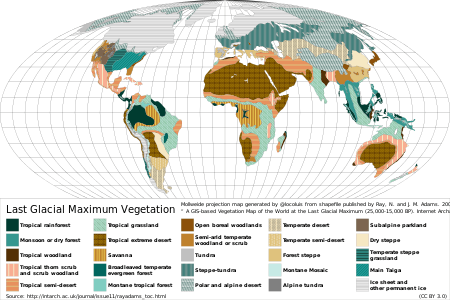

During the Pleistocene (2.58 million years BCE) glacial cycles, the Japanese islands may at times have been connected to the Eurasian Continent via the Korea Strait and Korean Peninsula or Sakhalin (Karafuto). At times, the Sea of Japan was said to be a frozen inner lake due to the lack of warm Tsushima Current and various plants and large animals, such as the Palaeoloxodon naumanni are believed to have spread into Japan.[46]

The Sea of Japan was a landlocked sea when the land bridge of East Asia existed circa 18,000 BCE. During the glacial maximum the marine elevation was 200 meters lower than 2018 CE. Thus Tsushima island in the Korea Strait was a land bridge that connected Kyushu and the southern tip of Honshu with the Korean peninsula. There was still several kilometers of sea to the west of the Ryukyu islands and most of the Sea of Japan was open sea due it having a mean depth of 1,752 m (5,748 ft). Comparatively, most of the Yellow Sea (Yellow Plane) had a Semi-arid climate (dry steppe), due it being relatively shallow with a mean depth of 44 m (144 ft). The Korean Peninsula was landlocked on the entire west and south side in the Yellow Plane.[47] The onset of formation of the Japan Arc was in the Early Miocene (23 million years ago).[48] The Early Miocene period was when the Sea of Japan started to open, and the northern and southern parts of the Japanese archipelago separated from each other.[48] The Sea of Japan expanded during the Miocene.[48]

The north part of the Japanese archipelago was further fragmented later until orogenesis of the northeastern Japanese archipelago began in the later Late Miocene.[48] The south part of the Japanese archipelago remained as a relatively large landmass.[48] The land area had expanded northward in the Late Miocene.[48] The orogenesis of high mountain ranges in northeastern Japan started in Late Miocene and lasted in Pliocene.[48]

As world sea level dropped during the advance of the last Ice Age (115,000 BCE till 9682 BCE), the exit straits of the Sea of Japan one by one dried and closed. The deepest, and thus the last to close, is the western channel of the Korea Strait. There is controversy as to whether or not the Sea of Japan became a huge cold inland lake.[49] The Japanese archipelago's Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, the Ryukyu islands and Nanpō Islands had a taiga biome (open boreal woodlands). It was characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces and larches. Hokkaido, Karafuto (Sakhalin) and the Kuril islands had mammoth steppe biome (steppe-tundra). The vegetation was dominated by palatable high-productivity grasses, herbs and willow shrubs.

Present

The Sea of Japan has a surface area of about 978,000 km2 (378,000 sq mi), a mean depth of 1,752 m (5,748 ft) and a maximum depth of 3,742 m (12,277 ft). It has a carrot-like shape, with the major axis extending from southwest to northeast and a wide southern part narrowing toward the north. The coastal length is about 7,600 km (4,700 mi) with the largest part (3,240 km or 2,010 mi) belonging to Russia. The sea extends from north to south for more than 2,255 km (1,401 mi) and has a maximum width of about 1,070 km (660 mi).[50]

It has three major basins: the Yamato Basin in the southeast, the Japan Basin in the north and the Tsushima Basin (Ulleung Basin) in the southwest.[24] The Japan Basin is of oceanic origin and is the deepest part of the sea, whereas the Tsushima Basin is the shallowest with the depths below 2,300 m (7,500 ft).[50] On the eastern shores, the continental shelves of the sea are wide, but on the western shores, particularly along the Korean coast, they are narrow, averaging about 30 km (19 mi).

The geographical location of the Japanese archipelago has defined the Sea of Japan for millions of years. Without the Japanese archipelago it would just be the Pacific Ocean. The term has been the international standard since at least the early 19th century.[51] The International Hydrographic Organization, the international governing body for the naming bodies of water around the world, in 2012 recognized the term "Sea of Japan" as the only title for the sea.[52]

Natural Resources

Japan is scarce in critical natural resources and has long been heavily dependent on imported energy and raw materials.[53][2] The oil crisis in 1973 encouraged the efficient use of energy.[54] Japan has therefore aimed to diversify its sources and maintain high levels of energy efficiency.[55]

There are small deposits of coal, oil, iron and minerals in the Japanese archipelago.[2] There is a major fishing industry due to Japan's large maritime territory. There are major untapped marine resources in the Exclusive Economic Zone of Japan. Most of these underwater resources at the seabed have not been exploited yet. As of 2018 there is not much deep sea mining to retrieve minerals or deepwater drilling on the ocean floor in Japan's EEZ.

Japan maintains one of the world's largest fishing fleets and accounts for nearly 15% of the global catch (2014).[56] In 2005, Japan ranked sixth in the world in tonnage of fish caught.[57] Japan captured 4,074,580 metric tons of fish in 2005, down from 4,987,703 tons in 2000 and 9,864,422 tons in 1980.[58] In 2003, the total aquaculture production was predicted at 1,301,437 tonnes.[59] In 2010, Japan's total fisheries production was 4,762,469 fish.[60] Offshore fisheries accounted for an average of 50% of the nation's total fish catches in the late 1980s although they experienced repeated ups and downs during that period.

As of 2011, 46.1% of energy in Japan was produced from petroleum, 21.3% from coal, 21.4% from natural gas, 4.0% from nuclear power and 3.3% from hydropower. Nuclear power is a major domestic source of energy and produced 9.2 percent of Japan's electricity, as of 2011, down from 24.9 percent the previous year.[61] Following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami disaster in 2011, the nuclear reactors were shut down. Thus Japan's industrial sector became even more dependent than before on imported fossil fuels. By May 2012 all of the country's nuclear power plants were taken offline because of ongoing public opposition following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in March 2011, though government officials continued to try to sway public opinion in favor of returning at least some of Japan's 50 nuclear reactors to service.[62] Shinzo Abe’s government seeks to restart the nuclear power plants that meet strict new safety standards and is emphasizing nuclear energy’s importance as a base-load electricity source.[2] As of November 2014, two reactors at Sendai are likely to restart in early 2015.[63] In August 2015, Japan successfully restarted one nuclear reactor at the Sendai Nuclear Power Plant in Kagoshima prefecture, and several other reactors around the country have since resumed operations. Opposition from local governments has delayed several restarts that remain pending.

Reforms of the electricity and gas sectors, including full liberalization of Japan’s energy market in April 2016 and gas market in April 2017, constitute an important part of Prime Minister Abe’s economic program.[2]

On 3 July 2018, Japan's government pledged to increase renewable energy sources from 15% to 22-24% including wind and solar by 2030. Nuclear energy will provide 20% of the country's energy needs as an emissions-free energy source. This will help Japan meet climate change commitments.[64]

Climate

{{Citation needed|reason=Climate paragraphs need citations|date=October 2018}}

Most regions of Japan, such as much of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, belong to the temperate zone with humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) characterized by four distinct seasons. However, its climate varies from cool humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) in the north such as northern Hokkaido, to warm tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south such as Ishigaki in the Yaeyama Islands.

The two primary factors influences in Japan's climate are a location near the Asian continent and the existence of major oceanic currents. Two major ocean currents affect Japan: the warm Kuroshio Current (Black Current; also known as the Japan Current); and the cold Oyashio Current (Parent Current; also known as the Okhotsk Current). The Kuroshio Current flows northward on the Pacific side of Japan and warms areas as north as the South Kantō region; a small branch, the Tsushima Current, flows up the Sea of Japan side. The Oyashio Current, which abounds in plankton beneficial to coldwater fish, flows southward along the northern Pacific, cooling adjacent coastal areas. The intersection of these currents at 36 north latitude is a bountiful fishing ground.

Climate Zones

Japan's varied geographical features divide it into six principal climatic zones.

- Hokkaido (北海道 Hokkaidō): Belonging to the humid continental climate, Hokkaido has long, cold winters and cool summers. Precipitation is not great.

- Sea of Japan (日本海 Nihonkai): The northwest seasonal wind in winter gives heavy snowfall, which south of Tohoku mostly melts before the beginning of spring. In summer it is a little less rainy than the Pacific area but sometimes experiences extreme high temperatures due to the foehn wind phenomenon.

- Central Highland (中央高地 Chūō-kōchi): A typical inland climate gives large temperature variations between summers and winters and between days and nights. Precipitation is lower than on the coast due to rain shadow effects.

- Seto Inland Sea (瀬戸内海 Setonaikai): The mountains in the Chūgoku and Shikoku regions block the seasonal winds and bring mild climate and many fine days throughout the year.

- Pacific Ocean (太平洋 Taiheiyō): The climate varies greatly between the north and the south but generally winters are significantly milder and sunnier than those of the side that faces the Sea of Japan. Summers are hot due to the southeast seasonal wind. Precipitation is very heavy in the south, and heavy in the summer in the north. The climate of the Ogasawara Island chain in the Pacific Ocean ranges from a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) to tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw) with temperatures being warm to hot all year round.

- Ryukyu Islands (南西諸島 Nansei-shotō): The climate of these islands ranges from humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) in the north to tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south with warm winters and hot summers. Precipitation is very high, and is especially affected by the rainy season and typhoons.

Temperature and Rainfall

As an island nation, Japan has the 6th longest coastline in the world.[65][66] A few prefectures are landlocked: Gunma, Tochigi, Saitama, Nagano, Yamanashi, Gifu, Shiga, and Nara. As Mt. Fuji and the coastal Japanese Alps provide a rain shadow, Nagano and Yamanashi Prefectures receive the least precipitation in Honshu, though it still exceeds 900 millimetres (35 in) annually. A similar effect is found in Hokkaido, where Okhotsk Subprefecture receives as little as 750 millimetres (30 in) per year. All other prefectures have coasts on the Pacific Ocean, Sea of Japan, Seto Inland Sea or have a body of salt water connected to them. Two prefectures—Hokkaido and Okinawa—are composed entirely of islands.

Japan is generally a rainy country with high humidity. Because of its wide range of latitude, seasonal winds and different types of ocean currents, Japan has a variety of climates, with a latitude range of the inhabited islands from 24° to 46° north, which is comparable to the range between Nova Scotia and The Bahamas in the east coast of North America. Tokyo is at about 35 degrees north latitude, comparable to that of Tehran, Athens, or Las Vegas.

Regional climatic variations range from humid continental in the northern island of Hokkaido extending down through northern Japan to the Central Highland, then blending with and eventually changing to a humid subtropical climate on the Pacific Coast and ultimately reaching tropical rainforest climate on the Yaeyama Islands of the Ryukyu Islands. Climate also varies dramatically with altitude and with location on the Pacific Ocean or on the Sea of Japan.

Northern Japan has warm summers but long, cold winters with heavy snow. Central Japan in its elevated position, has hot summers and moderate to short winters with some areas having very heavy snow, and southwestern Japan has long hot summer and short mild winters. The generally temperate climate exhibits marked seasonal variation such as the blooming of the spring cherry blossoms, the calls of the summer cicada and fall foliage colors that are celebrated in art and literature.

The hottest temperature ever measured in Japan, 41.1 °C (106.0 °F), occurred in Kumagaya on 23 July 2018.[67] and the coldest was −41.0 °C (−41.8 °F) recorded at Asahikawa, Hokkaidō on 25 January 1902.

Summer

The climate from June to September is marked by hot, wet weather brought by tropical airflows from the Pacific Ocean and Southeast Asia. These airflows are full of moisture and deposit substantial amounts of rain when they reach land. There is a marked rainy season, beginning in early June and continuing for about a month. It is followed by hot, sticky weather. Five or six typhoons pass over or near Japan every year from early August to early October, sometimes resulting in significant damage. Annual precipitation averages between 1,000 and 2,500 mm (40 and 100 in) except for the areas such as Kii Peninsula and Yakushima Island which is Japan's wettest place[68] with the annual precipitation being one of the world's highest at 4,000 to 10,000 mm.[69]

Maximum precipitation, like the rest of East Asia, occurs in the summer months except on the Sea of Japan coast where strong northerly winds produce a maximum in late autumn and early winter. Except for a few sheltered inland valleys during December and January, precipitation in Japan is above 25 millimetres (1 in) of rainfall equivalent in all months of the year, and in the wettest coastal areas it is above 100 millimetres (4 in) per month throughout the year.

Mid June to mid July is generally the rainy season in Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, excluding Hokkaidō since the seasonal rain front or baiu zensen (梅雨前線) dissipates in northern Honshu before reaching Hokkaido. In Okinawa, the rainy season starts early in May and continues until mid June. Unlike the rainy season in mainland Japan, it rains neither everyday nor all day long during the rainy season in Okinawa. Between July and October, typhoons, grown from tropical depressions generated near the equator, can attack Japan with furious rainstorms.

Winter

In winter, the Siberian High develops over the Eurasian land mass and the Aleutian Low develops over the northern Pacific Ocean. The result is a flow of cold air southeastward across Japan that brings freezing temperatures and heavy snowfalls to the central mountain ranges facing the Sea of Japan, but clear skies to areas fronting on the Pacific.

The warmest winter temperatures are found in the Nanpō and Bonin Islands, which enjoy a tropical climate due to the combination of latitude, distance from the Asian mainland, and warming effect of winds from the Kuroshio, as well as the Volcano Islands (at the latitude of the southernmost of the Ryukyu Islands, 24° N). The coolest summer temperatures are found on the northeastern coast of Hokkaidō in Kushiro and Nemuro Subprefectures.

Sunshine

Sunshine, in accordance with Japan’s uniformly heavy rainfall, is generally modest in quantity, though no part of Japan receives the consistently gloomy fogs that envelope the Sichuan Basin or Taipei. Amounts range from about six hours per day in the Inland Sea coast and sheltered parts of the Pacific Coast and Kantō Plain to four hours per day on the Sea of Japan coast of Hokkaidō. In December there is a very pronounced sunshine gradient between the Sea of Japan and Pacific coasts, as the former side can receive less than 30 hours and the Pacific side as much as 180 hours. In summer, however, sunshine hours are lowest on exposed parts of the Pacific coast where fogs from the Oyashio current create persistent cloud cover similar to that found on the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin.

Extreme points

Japan extends from 20° to 45° north longitude (Okinotorishima to Benten-jima) and from 122° to 153° east latitude (Yonaguni to Minami Torishima).[13] These are the points that are farther north, south, east or west than any other location in Japan.

| Heading | Location | Prefecture | Bordering entity | Coordinates† | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (disputed) |

Cape Kamoiwakka on Etorofu | Hokkaido‡ | Sea of Okhotsk | 45°33′26″N 148°45′09″E / 45.55722°N 148.75250°E | [70] |

| North (undisputed) |

Benten-jima | Hokkaidō | La Pérouse Strait | 45°31′38″N 141°55′06″E / 45.52722°N 141.91833°E | [71] |

| South | Okinotorishima | Tokyo | Philippine Sea | 20°25′31″N 136°04′11″E / 20.42528°N 136.06972°E | |

| East | Minami Torishima | Tokyo | Pacific Ocean | 24°16′59″N 153°59′11″E / 24.28306°N 153.98639°E | |

| West | Yonaguni | Okinawa | East China Sea | 24°26′58″N 122°56′01″E / 24.44944°N 122.93361°E | The westernmost Monument of Japan |

Japan's main islands

The four main islands of Japan are Hokkaidō, Honshū, Kyūshū and Shikoku. All of these points are accessible to the public.

| Heading | Location | Prefecture | Bordering entity | Coordinates† | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Cape Sōya | Hokkaidō | La Pérouse Strait | 45°31′22″N 141°56′11″E / 45.52278°N 141.93639°E | |

| South | Cape Sata | Kagoshima | East China Sea | 30°59′39″N 130°39′38″E / 30.99417°N 130.66056°E | |

| East | Cape Nosappu | Hokkaidō | Pacific Ocean | 43°23′06″N 145°49′03″E / 43.38500°N 145.81750°E | |

| West | Kōzakihana | Nagasaki | East China Sea | 33°13′04″N 129°33′09″E / 33.21778°N 129.55250°E |

Extreme altitudes

| Extremity | Name | Altitude | Prefecture | Coordinates† | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest | Mount Fuji | 3,776 m (12,388 ft) | Yamanashi | 35°21′29″N 138°43′52″E / 35.35806°N 138.73111°E | [72] |

| Lowest (man-made) |

Hachinohe mine | −170 m (−558 ft) | Aomori | 40°27′10″N 141°32′16″E / 40.45278°N 141.53778°E | [73] |

| Lowest (natural) |

Hachirōgata | −4 m (−13 ft) | Akita | 39°54′50″N 140°01′15″E / 39.91389°N 140.02083°E | [72] |

Natural hazards

Geological hazards

Earthquakes and Tsunami

Japan is substantially prone to earthquakes, tsunami and volcanoes due to its location along the Pacific Ring of Fire.[74] It has the 15th highest natural disaster risk as measured in the 2013 World Risk Index.[75]

As many as 1,500 earthquakes are recorded yearly, and magnitudes of 4 to 7 are common. Minor tremors occur almost daily in one part of the country or another, causing slight shaking of buildings. Major earthquakes occur infrequently; the most famous in the twentieth century was the great Kantō earthquake of 1923, in which 130,000 people died. Undersea earthquakes also expose the Japanese coastline to danger from tsunamis (津波).

Destructive earthquakes, often resulting in tsunami, occur several times each century.[12] The 1923 Tokyo earthquake killed over 140,000 people.[76] More recent major quakes are the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, a 9.1-magnitude[77] quake which hit Japan on March 11, 2011. It triggered a large tsunami and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, one of the worst disasters in the history of nuclear power.[78]

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake was the largest ever recorded in Japan and is the world's fourth largest earthquake to strike since 1900, according to the U.S. Geological Service. It struck offshore about 371 kilometres (231 mi) northeast of Tokyo and 130 kilometres (81 mi) east of the city of Sendai, and created a massive tsunami that devastated Japan's northeastern coastal areas. At least 100 aftershocks registering a 6.0 magnitude or higher have followed the main shock. At least 15,000 people died as a result.

Reclaimed land and man-made islands are particularly susceptible to liquefaction during an earthquake. As a result, there are specific earthquake resistance standards and ground reform work that applies to all construction in these areas. In an area that was possibly reclaimed in the past, old maps and land condition drawings are checked and drilling is carried out to determine the strength of the ground. However this can be very costly, so for a private residential block of land, a swedish weight sounding test is more common.[18]

Japan has become a world leader in research on causes and prediction of earthquakes. The development of advanced technology has permitted the construction of skyscrapers even in earthquake-prone areas. Extensive civil defence efforts focus on training in protection against earthquakes, in particular against accompanying fire, which represents the greatest danger.

Volcanic eruptions

Japan has 108 active volcanoes. That's 10% of all active volcanoes in the world. Japan has stratovolcanoes near the subduction zones of the tectonic plates. During the twentieth century several new volcanoes emerged, including Shōwa-shinzan on Hokkaido and Myōjin-shō off the Bayonnaise Rocks in the Pacific.[12] In 1991, Japan's Unzen Volcano on Kyushu about 40 km (25 mi) east of Nagasaki, awakened from its 200-year slumber to produce a new lava dome at its summit. Beginning in June, repeated collapse of this erupting dome generated ash flows that swept down the mountain's slopes at speeds as high as 200 km/h (120 mph). Unzen erupted in 1792 and killed more than 15,000 people. It is the worst volcanic disaster in the country's recorded history.[79]

Mount Fuji is a dormant stratovolcano that last erupted on 16 December 1707 till about 1 January 1708.[80][81] The Hōei eruption of Mount Fuji didn't have a lava flow, but it did release some 800 million cubic metres (28×109 cu ft) of volcanic ash. It spread over vast areas around the volcano and reached Edo almost 100 kilometres (60 mi) away. Cinders and ash fell like rain in Izu, Kai, Sagami, and Musashi provinces.[82] In Edo, the volcanic ash was several centimeters thick.[83] The eruption is rated a 5 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.[84] The eruption is rated a 5 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.[85]

Meteorological hazards

Typhoons

Another common hazard are several typhoons that reach Japan from the Pacific every year. Heavy snowfall during the winter in the snow country regions, cause landslides, flooding, and avalanches.

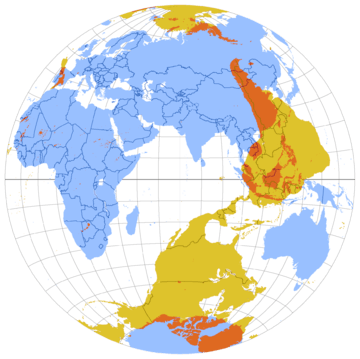

Antipodes

The only part of Japan with antipodes over land are the Ryukyu Islands, though the islands off the western coast of Kyūshū are close.

The northernmost antipodal island in the Ryukyu Island chain, Nakanoshima, is opposite the Brazilian coast near Capão da Canoa. The other islands south to the Straits of Okinawa correspond to southern Brazil, with Gaja Island being opposite the outskirts of Santo Antônio da Patrulha, Takarajima with Jua, Amami Ōshima covering the villages of Carasinho and Fazenda Pae João, Ginoza, Okinawa with Palmas, Paraná, the Kerama Islands with Pato Branco, Tonaki Island with São Lourenço do Oeste, and Kume Island corresponding to Palma Sola. The main Daitō Islands correspond to near Guaratuba, with Oki Daitō Island near Apiaí.

The Sakishima Islands beyond the straits are antipodal to Paraguay, from the Brazilian border almost to Asunción, with Ishigaki overlapping San Isidro de Curuguaty, and the uninhabited Senkaku Islands surrounding Villarrica.

Environmental issues

Environment

Current issues

In the 2006 environment annual report,[86] the Ministry of Environment reported that current major issues are: global warming and preservation of the ozone layer, conservation of the atmospheric environment, water and soil, waste management and recycling, measures for chemical substances, conservation of the natural environment and the participation in the international cooperation.

International agreements

Party to: Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes (Basel Convention), Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Ozone Layer Protection (Montreal Protocol), Ship Pollution (MARPOL 73/78), Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands (Ramsar Convention), Whaling

Signed and ratified: Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "平成29年全国都道府県市区町村別の面積を公表". 国土地理院 (Geospatial Information Authority of Japan). Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Japan". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "Shinano River". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "Lake Biwa". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- 1 2 "Water Supply in Japan". Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Archived from the original (website) on January 26, 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- 1 2 "離島とは(島の基礎知識)". Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Archived from the original (website) on November 13, 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- 1 2 "日本の領海等概念図". 海上保安庁海洋情報部. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- 1 2 "Forest area". The World Bank Group. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ↑ "地形分類" (PDF). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barnes, Gina L. (2003). "Origins of the Japanese Islands: The New "Big Picture"" (PDF). University of Durham. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- 1 2 Sella, Giovanni F.; Dixon, Timothy H.; Mao, Ailin (2002). "REVEL: A model for Recent plate velocities from space geodesy". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 107 (B4): ETG 11–1-ETG 11–30. doi:10.1029/2000jb000033. ISSN 0148-0227.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tectonics and Volcanoes of Japan". Oregon State University. Archived from the original on February 4, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- 1 2 GeoHack - Geography of Japan. GeoHack. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ↑ 最新結果一覧 政府統計の総合窓口 GL08020101. Statistics Bureau of Japan. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ↑ Regions of Japan on japan-guide.com

- ↑ "島とは何か". Center for Research and Promotion of Japanese Islands. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- 1 2 "Japan granted more continental shelf". Upi.com. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Reclaimed Land in Japan". Japan Property Central. Archived from the original on 2018-02-26. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- ↑ "The History of Ogata-Mura | Ogata-mura". Ogata.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-04-17.

- ↑ "Japan Fact Sheet". Japan Reference. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ Seno et al., 1996 Journal of Geophysical Research; https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/96JB00532

- ↑ Apel et al., 2006 Geophysical Research Letters; http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/wol1/doi/10.1029/2006GL026077/full

- ↑ http://www.stephan-mueller-spec-publ-ser.net/4/147/2009/smsps-4-147-2009.pdf

- 1 2 Sea of Japan, Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- ↑ Martínez-López, M.R., Mendoza, C., (2016). "Acoplamiento sismogénico en la zona de subducción de Michoacán-Colima-Jalisco,México" (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana (in Spanish). 68 (2): 199–214.

- ↑ "Orogenese". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). February 14, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Yurie SAWAHATA, Makoto Okada, Jun Hosoi, Kazuo Amano, "Paleomagnetic study of Neogene sediments in strike-slip basins along the Tanakura Fault". confit.atlas.jp. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ Rhea, S., et al., 2010, Seismicity of the Earth 1900–2007, Kuril-Kamchatka arc and vicinity, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010-1083-C, 1 map sheet, scale 1:5,000,000 http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1083/c/

- ↑ O'Hara, Design by J. Morton, V. Ferrini, and S. "GMRT Overview". www.gmrt.org. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

- ↑ "Locator map". Expedition to the Mariana forearc. School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology at the University of Hawaii.

- ↑ Deep current structure above the Izu-Ogasawara Trench

- 1 2 "Crustal structure of the ocean-island arc transition at the mid Izu-Ogasawara(Bonin) arc margin" (PDF). Earth, Planets and Space. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Geology of Japan|Geological Survey of Japan, AIST|産総研地質調査総合センター / Geological Survey of Japan, AIST". gsj.jp. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ Davison C (1916-09-21). "The Sakura-Jima Eruption of January, 1914". Nature. 98 (2447): 57–58. Bibcode:1916Natur..98...57D. doi:10.1038/098057b0.

- ↑ "Sakurajima, Japan's Most Active Volcano". nippon.com. Nippon Communications Foundation. May 16, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ↑ "しんとう". Hokkaidō Shinbun. 12 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Nishinoshima". Kotobank. Asahi Shinbun. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ "Lava flow connects new islet with Nishinoshima island". Asahi Shimbun. 26 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ↑ Nakano, Shun. "Kaitei chikei". Nishinoshima Kazan (in Japanese). Geological Survey of Japan. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ "Quake shifted Japan by over two metres". Deutsche Welle. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Chang, Kenneth (13 March 2011). "Quake Moves Japan Closer to U.S. and Alters Earth's Spin". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (14 March 2011). "How the quake has moved Japan". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Reilly, Michael (12 March 2011). "Japan quake fault may have moved 40 metres". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Japan seabed shifted 24 metres after March quake | Reuters.com Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Jiji Press, "March temblor shifted seabed by 50 metres (160 ft)", Japan Times, 3 December 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Park, S.-C.; Yoo, D.-G.; Lee, C.-W.; Lee, E.-I. (26 September 2000). "Last glacial sea-level changes and paleogeography of the Korea (Tsushima) Strait". Geo-Marine Letters. 20 (2): 64–71. doi:10.1007/s003670000039.

- ↑ Totman, Conrad D. (2004). Pre-Industrial Korea and Japan in Environmental Perspective. ISBN 978-9004136267. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kameda Y. & Kato M. (2011). "Terrestrial invasion of pomatiopsid gastropods in the heavy-snow region of the Japanese Archipelago". BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 118. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-118.

- ↑ Park, S.-C; Yoo, D.-G; Lee, C.-W; Lee, E.-I (2000). "Last glacial sea-level changes and paleogeography of the Korea (Tsushima) Strait". Geo-Marine Letters. 20 (2): 64–71. doi:10.1007/s003670000039.

- 1 2 Sea of Japan, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- ↑ "Japanese Basic Position on the Naming of the "Japan Sea"". Japan Coast Guard. March 1, 2005. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011.

- ↑ Kyodo News, "IHO nixes 'East Sea' name bid", Japan Times, 28 April 2012, p. 2; Rabiroff, Jon, and Yoo Kyong Chang, "Agency rejects South Korea's request to rename Sea of Japan", Stars and Stripes, 28 April 2012, p. 5.

- ↑ "Can nuclear power save Japan from peak oil?". Our World 2.0. February 2, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ↑ Sekiyama, Takeshi. "Japan's international cooperation for energy efficiency and conservation in Asian region" (PDF). Energy Conservation Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Japan". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ↑ "World review of fisheries and aquaculture". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Brown, Felicity (September 2, 2003). "Fish capture by country". The Guardian. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Japan". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ "World fisheries production, by capture and aquaculture, by country (2010)" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Energy". Statistical Handbook of Japan 2013. Statistics Bureau. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ Tsukimori, Osamu (May 5, 2012). "Japan nuclear power-free as last reactor shuts". Reuters. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Japan governor approves Sendai reactor restart". BBC News. November 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Japan aims for 24% renewable energy but keeps nuclear central". Phys.org. July 3, 2018. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ↑ "The length of the coast for the countries of the world". Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ↑ "Coastline Lengths / Countries of the World". world.bymap.org. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ↑ Kochi Prefecture sees highest temperature ever recorded in Japan - 41 Archived 2013-08-13 at the Wayback Machine. - Asahi Shimbun

- ↑ "Japan Climate Charts Index". Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ↑ "Yakushima World Heritage property". Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ↑ "Google Maps (Cape Kamoiwakka)". Google. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "Google Maps (Bentenjima)". Google. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- 1 2 "Japan: Geography". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ 施設見学ガイド 八戸鉱山株式会社 八戸石灰鉱山(八戸キャニオン). The Information Center for Energy and Environment Education (in Japanese). Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ Israel, Brett (March 14, 2011). "Japan's Explosive Geology Explained". Live Science. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ 2013 World Risk Report Archived August 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ James, C.D. (2002). "The 1923 Tokyo Earthquake and Fire" (PDF). University of California Berkeley. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 16, 2007. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ "M 9.1 – near the east coast of Honshu, Japan". Earthquake.usgs.gov. July 11, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ↑ Fackler, Martin; Drew, Kevin (March 11, 2011). "Devastation as Tsunami Crashes Into Japan". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ↑

- ↑ "Active Volcanoes of Japan". AIST. Geological Survey of Japan. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Mount Fuji". Britannica Online. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ↑ Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Annales des empereurs du japon, p. 416.

- ↑ Archived March 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Fuji — Eruption History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Fuji — Eruption History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ Annual Report on the Environment in Japan 2006, Ministry of the Environment

- All Geography of Japan information taken from the "Japan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geography of Japan. |

- "Colton's Japan: Nippon, Kiusiu, Sikok, Yesso and the Japanese Kuriles" a map from 1855

- Terrain of Japan - GJI Maps(Geospatial Information Authority of Japan)