Bank of Japan

| |||

| Headquarters | Chūō, Tokyo, Japan | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°41′10″N 139°46′17″E / 35.6861°N 139.7715°E | ||

| Established |

June 27, 1882 / October 10, 1882 | ||

| Governor |

Haruhiko Kuroda (March 20, 2013 - ) | ||

| Central bank of | Japan | ||

| Currency |

Japanese yen JPY (ISO 4217) | ||

| Bank rate | 0%-0.10% | ||

| Website | www.boj.or.jp | ||

The Bank of Japan (日本銀行 Nippon Ginkō, BOJ, JASDAQ: 8301) is the central bank of Japan.[1] The bank is often called Nichigin (日銀) for short. It has its headquarters in Chūō, Tokyo.[2]

History

Like most modern Japanese institutions, the Bank of Japan was founded after the Meiji Restoration. Prior to the Restoration, Japan's feudal fiefs all issued their own money, hansatsu, in an array of incompatible denominations, but the New Currency Act of Meiji 4 (1871) did away with these and established the yen as the new decimal currency, which had parity with the Mexican silver dollar.[3] The former han (fiefs) became prefectures and their mints became private chartered banks which, however, initially retained the right to print money. For a time both the central government and these so-called "national" banks issued money. A period of unanticipated consequences was ended when the Bank of Japan was founded in Meiji 15 (October 10, 1882), under the Bank of Japan Act 1882 (June 27, 1882), after a Belgian model. It has since been partly privately owned (its stock is traded over the counter, hence the stock number).[4] A number of modifications based on other national banks were encompassed within the regulations under which the bank was founded.[5] The institution was given a monopoly on controlling the money supply in 1884, but it would be another 20 years before the previously issued notes were retired.[6]

Following the passage of the Convertible Bank Note Regulations (May 1884), the Bank of Japan issued its first banknotes in 1885 (Meiji 18). Despite some small glitches—for example, it turned out that the konjac powder mixed in the paper to prevent counterfeiting made the bills a delicacy for rats—the run was largely successful. In 1897, Japan joined the gold standard,[7] and in 1899 the former "national" banknotes were formally phased out.

Since its Meiji era beginnings, the Bank of Japan has operated continuously from main offices in Tokyo and Osaka.

Reorganization

The Bank of Japan was reorganized in 1942[1] (fully only after May 1, 1942), under the Bank of Japan Act of 1942 (日本銀行法 昭和17年法律第67号), promulgated on February 24, 1942. There was a brief post-war period during the Occupation of Japan when the bank's functions were suspended, and military currency was issued. In 1949, the bank was again restructured.[1]

In the 1970s, the bank's operating environment evolved along with the transition from a fixed foreign currency exchange rate and a rather closed economy to a large open economy with a variable exchange rate.[8]

During the entire post-war era, until at least 1991, the Bank of Japan's monetary policy has primarily been conducted via its 'window guidance' (窓口指導) credit controls (which are the model for the Chinese central bank's primary tool of monetary policy implementation), whereby the central bank would impose bank credit growth quotas on the commercial banks. The tool was instrumental in the creation of the 'bubble economy' of the 1980s. It was implemented by the Bank of Japan's then "Business Department" (営業局), which was headed during the "bubble years" from 1986 to 1989 by Toshihiko Fukui (who became deputy governor in the 1990s and governor in 2003).[9]

A major 1997 revision of the Bank of Japan Act was designed to give it greater independence;[10] however, the Bank of Japan has been criticized for already possessing excessive independence and lacking in accountability before this law was promulgated.[11] A certain degree of dependence might be said to be enshrined in the new Law, article 4 of which states:

- In recognition of the fact that currency and monetary control is a component of overall economic policy, the Bank of Japan shall always maintain close contact with the government and exchange views sufficiently, so that its currency and monetary control and the basic stance of the government's economic policy shall be mutually harmonious.

However, since the introduction of the new law, the Bank of Japan has rebuffed government requests to stimulate the economy.[12]

The trail of policies

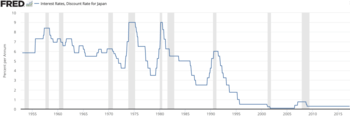

When the Nixon shock happened in August 1971, BOJ should have appreciated the currency in order to avoid inflation. However, they still kept the fixed exchange rate as 360Yen/$ for two weeks, so it caused excess liquidity. In addition, they persisted with the Smithsonian rate (308Yen/$), and continued monetary easing until 1973. This created a greater than 10% inflation rate at that time. In order to control the stagflation, they raised the official bank rate from 7% to 9% and gradually skyrocketing prices ended in 1978. In 1979, when the energy crisis happened, they raised the official bank rate rapidly. BOJ succeeded in a quick economic recovery. After overcoming the crisis, they reduced the official bank rate. In 1980, BOJ reduced the official bank rate from 9.0% to 8.25% in August, to 7.25% in November, and to 5.5% in December in 1981. Reaganomics was set in America, and USD became strong. However, Japan tried to make fiscal reconstruction at that time, so they did not stop their financial regulation. In 1985, the agreement of G5 nations, known as the Plaza agreement, USD slipped down and Yen/USD changed from 240yen/$ to 200yen/$ at the end of 1985. Even in 1986, USD continued to fall and reached 160yen/$. In order to escape deflation, BOJ cut the official bank rate from 5% to 4.5% in January, to 4.0% in March, to 3.5% in April, 3.0% in November. At the same time, the government tried to raise the demand in Japan in 1985, and did economy policy in 1986. However, the market was confused about the rapid fall of USD. After Louvre Accord in February 1987, BOJ decreased the official bank rate from 3% to 2.5%, but JPN/USD was 140yen/$ at that time and reached 125yen/$ in the end of 1987. BOJ kept the official bank rate at 2.5% until May in 1989. The financial and fiscal regulation led to a widespread over-valuing of real estate and investments and Japan faced a bubble at that time. After 1990, the stock market and real asset market fell, at that time BOJ regulated markets until 1991 in order to end the bubble. In 1994, a terrible earthquake happened and Japanese yen became weaker and weaker. JPM/USD reached 80yen/$, so BOJ had to reduce the office bank rate to 0.5% and Japanese yen recovered. The long deflation for 20 years started at that time. In 1999, BOJ started zero-interest-rate policy, but they ended it despite government opposition when the IT bubble happened in 2000. However, Japan faced economic bubble burst in 2001, BOJ adopted the balance of current account as the main operating target for the adjustment of the financial market in March 2001 (quantitative relaxation policy), shifting from the zero-interest-rate policy. From 2003 to 2004, Japanese government did exchange intervention operation in huge amount, and the economy recovered a lot. In March 2006, BOJ finished qualitative easing, and finished the zero-interest-rate policy in June and raised to 0.25%. In 2008, the financial crisis happened, and Japanese economy turned to bad again. BOJ reduced uncollateralized call rate to 0.3% and adopted the supplemental balance of current account policy. In December 2008, BOJ reduced uncollateralized call rate again to 0.1% and they started to buy Japanese Government Bond (JGB). [13]

Curbing deflation

Following the election of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, the Bank of Japan has, with Abe's urging, taken proactive steps to curb deflation in Japan. On October 30, 2012, The Bank of Japan announced that it has undertaken further monetary-easing action for the second time in a month.[14] Under the leadership of new Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, the Bank of Japan released a statement on April 5, 2013 announcing that it would be purchasing securities and bonds at a rate of 60-70 trillion yen a year in an attempt to double Japan's money base in two years.[15] By 2016 it was apparent three years of monetary easing had had little effect on deflation, and the Bank of Japan instigated a review of its monetary stimulus program.[16]

Mission

According to its charter, the missions of the Bank of Japan are

- Issuance and management of banknotes

- Implementation of monetary policy

- Providing settlement services and ensuring the stability of the financial system

- Treasury and government securities-related operations

- International activities

- Compilation of data, economic analyses and research activities

Location

The Bank of Japan is headquartered in Nihonbashi, Chūō, Tokyo, on the site of a former gold mint (the Kinza) and, not coincidentally, near the famous Ginza district, whose name means "silver mint". The Neo-baroque Bank of Japan building in Tokyo was designed by Tatsuno Kingo in 1896.

The Osaka branch in Nakanoshima is sometimes considered as the structure which effectively symbolizes the bank as an institution.

- Bank of Japan

The head office of the Bank of Japan located in Nihonbashi Mainoucho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo.

The head office of the Bank of Japan located in Nihonbashi Mainoucho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo. The Bank of Japan Osaka Branch

The Bank of Japan Osaka Branch

Governor

| Governor of the Bank of Japan | |

|---|---|

| Style | His Excellency |

| Appointer | The Prime Minister |

| Term length | Five years |

| Inaugural holder | Yoshihara Shigetoshi |

| Formation | October 6, 1882 |

The Governor of the Bank of Japan (総裁 sōsai) has considerable influence on the economic policy of the Japanese government. Japanese lawmakers endorse the Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda. He is seen to adopt Reflation policy as part of Abenomics.[17]

List of governors

| # | Governor | Took Office | Left Office |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yoshihara Shigetoshi | October 6, 1882 | December 19, 1887 |

| 2 | Tomita Tetsunosuke | February 21, 1888 | September 3, 1889 |

| 3 | Kawada Koichiro | September 3, 1889 | November 7, 1896 |

| 4 | Iwasaki Yanosuke | November 11, 1896 | October 20, 1898 |

| 5 | Tatsuo Yamamoto | October 20, 1898 | October 19, 1903 |

| 6 | Shigeyoshi Matsuo | October 20, 1903 | June 1, 1911 |

| 7 | Korekiyo Takahashi | June 1, 1911 | February 20, 1913 |

| 8 | Yatarō Mishima | February 28, 1913 | March 7, 1919[18] |

| 9 | Junnosuke Inoue (First) | March 13, 1919 | September 2, 1923 |

| 10 | Otohiko Ichiki | September 5, 1923 | May 10, 1927 |

| 11 | Junnosuke Inoue (Second) | May 10, 1927 | June 12, 1928 |

| 12 | Hisaakira Hijikata | June 12, 1928 | June 4, 1935 |

| 13 | Eigo Fukai | June 4, 1935 | February 9, 1937 |

| 14 | Seihin Ikeda | February 9, 1937 | July 27, 1937 |

| 15 | Toyotaro Yuki | July 27, 1937 | March 18, 1944 |

| 16 | Keizo Shibusawa | March 18, 1944 | October 9, 1945 |

| 17 | Eikichi Araki (First) | October 9, 1945 | June 1, 1946 |

| 18 | Hisato Ichimada | June 1, 1946 | December 10, 1954 |

| 19 | Eikichi Araki (Second) | December 11, 1954 | November 30, 1956 |

| 20 | Masamichi Yamagiwa | November 30, 1956 | December 17, 1964 |

| 21 | Makoto Usami | December 17, 1964 | December 16, 1969 |

| 22 | Tadashi Sasaki | December 17, 1969 | December 16, 1974 |

| 23 | Teiichiro Morinaga | December 17, 1974 | December 16, 1979 |

| 24 | Haruo Maekawa | December 17, 1979 | December 16, 1984 |

| 25 | Satoshi Sumita | December 17, 1984 | December 16, 1989 |

| 26 | Yasushi Mieno | December 17, 1989 | December 16, 1994 |

| 27 | Yasuo Matsushita | December 17, 1994 | March 20, 1998 |

| 28 | Masaru Hayami | March 20, 1998 | March 19, 2003 |

| 29 | Toshihiko Fukui | March 20, 2003 | March 19, 2008 |

| 30 | Masaaki Shirakawa | April 9, 2008 | March 19, 2013 |

| 31 | Haruhiko Kuroda | March 20, 2013 | Incumbent |

Monetary Policy Board

As of April 9, 2018, the board responsible for setting monetary policy consisted of the following 9 members:[19]

- Haruhiko Kuroda, Governor of the BOJ

- Masayoshi Amamiya, Deputy Governor of the BOJ

- Masazumi Wakatabe, Deputy Governor of the BOJ

- Yutaka Harada

- Yukitoshi Funo

- Makoto Sakurai

- Takako Masai

- Hitoshi Suzuki

- Goushi Kataoka

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric. (2005). "Nihon Ginkō" in Japan encyclopedia, p. 708., p. 708, at Google Books

- ↑ "Guide Map to the Bank of Japan Tokyo Head Office Archived 2009-06-04 at the Wayback Machine.." Bank of Japan. Retrieved on December 22, 2009.

- ↑ Nussbaum, "Banks", Bank of Japan, p. 69, at Google Books.

- ↑ Vande Walle, Willy et al. "Institutions and ideologies: the modernization of monetary, legal and law enforcement 'regimes' in Japan in the early Meiji-period (1868-1889)" (abstract). FRIS/Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2007; retrieved 2012-10-17.

- ↑ Longford, Joseph Henry. (1912). Japan of the Japanese, p. 289.

- ↑ Cargill, Thomas et al. (1997). The political economy of Japanese monetary policy, p. 10.

- ↑ Nussbaum, "Banks", Bank of Japan, p. 70, at Google Books

- ↑ Cargill, p. 197.

- ↑ Werner, Richard (2002). "Monetary Policy Implementation in Japan: What They Say vs. What they Do", Asian Economic Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 111–151; Werner, Richard (2001). Princes of the Yen, Armonk: M. E. Sharpe.

- ↑ Cargill, p. 19.

- ↑ Horiuchi, Akiyoshi (1993), "Japan" in Chapter 3, "Monetary policies" in Haruhiro Fukui, Peter H. Merkl, Hubrtus Mueller-Groeling and Akio Watanabe (eds), The Politics of Economic Change in Postwar Japan and West Germany, vol. 1, Macroeconomic Conditions and Policy Responses, London: Macmillan. Werner, Richard (2005), New Paradigm in Macroeconomics, London: Macmillan.

- ↑ See rebuffed requests by the government representatives at BOJ policy board meetings: e.g. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2010-09-09. or refusals to increase bond purchases: Bloomberg News.

- ↑ Kuroda Haruhiko(2013)財政金融政策の成功と失敗

- ↑ "Bank of Japan Expands Asset-Purchase Program". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Riley, Charles (April 4, 2013). "Bank of Japan takes fight to deflation". CNN.

- ↑ Stanley White (31 July 2016). "'Helicopter monet' talk takes flight as Bank of Japan runs out of runway". The Japan Times. Reuters. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ "Japan: The Great Reflation Play Of 2013". TheStreet.com. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ↑ Masaoka, Naoichi. (1914). Japan to America, p. 127.

- ↑ "Policy Board : 日本銀行 Bank of Japan". www.boj.or.jp. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

References

- Cargill, Thomas F., Michael M. Hutchison and Takatoshi Itō. (1997). The political economy of Japanese monetary policy. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262032476; OCLC 502984085

- Longford, Joseph Henry. (1912). Japan of the Japanese. New York: C. Scribner's sons. OCLC 2971290

- Masaoka, Naoichi. (1914). Japan to America: A Symposium of Papers by Political Leaders and Representative Citizens of Japan on Conditions in Japan and on the Relations Between Japan and the United States. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons (Japan Society). OCLC 256220

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301

- Vande Walle, Willy et al. "Institutions and ideologies: the modernization of monetary, legal and law enforcement 'regimes' in Japan in the early Meiji-period (1868-1889)" (abstract). FRIS/Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2007.

- Werner, Richard A. (2005). New Paradigm in Macroeconomics: Solving the Riddle of Japanese Macroeconomic Performance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403920737; ISBN 9781403920744; OCLC 56413058

- _____________. (2003). Princes of the Yen: Japan's Central Bankers and the Transformation of the Economy. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1048-5; OCLC 471605161

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bank of Japan. |

- Official website (in English)

- Building a national currency (1868-99)

- Japan and World Interest Rates, Interest Rates data and chart daily updated by ForexMotion

.jpg)