Sakhnin

Sakhnin

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Saḥnin, Saknin (Israeli pronunciation) |

View of Sakhnin | |

Sakhnin | |

| Coordinates: 32°52′N 35°18′E / 32.867°N 35.300°ECoordinates: 32°52′N 35°18′E / 32.867°N 35.300°E | |

| Grid position | 177/252 PAL |

| Country |

|

| District | Northern |

| Founded |

1500 BCE (as Sagone) 1995 (Israeli city) |

| Government | |

| • Type | City (from 1995) |

| • Mayor | Mazin G'Nayem |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,816 dunams (9.816 km2 or 3.790 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 30,548 |

| • Density | 3,100/km2 (8,100/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Sukhnin, from personal name,[2] |

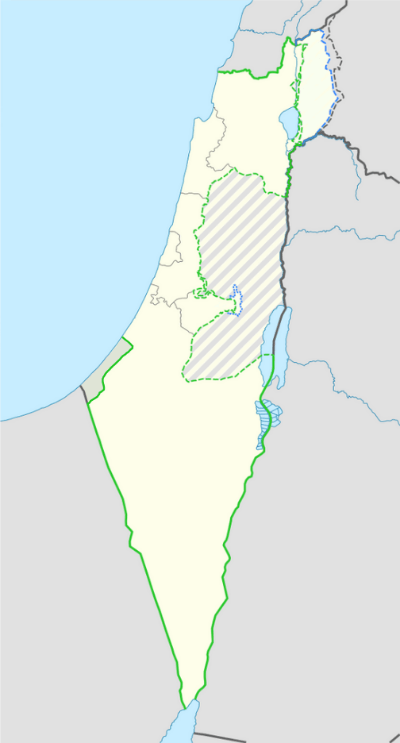

Sakhnin (Arabic: سخنين; Hebrew: סַחְ'נִין or סִכְנִין Sikhnin) is an Arab city in Israel's Northern District. It is located in the Lower Galilee, about 23 kilometres (14 mi) east of Acre. Sakhnin was declared a city in 1995. In 2017 its population was 30,548,[1] mostly Muslim with a sizable Christian minority.[3] Sakhnin is home to the largest population of Sufi Muslims within Israel, with approximately 80 members.

Geography

Sakhnin is built over three hills and is located in a valley surrounded by mountains, the highest one being 602 meters high. Its rural landscape is almost entirely covered by olive and fig groves as well as oregano and sesame shrubs.

History

Settlement at Sakhnin dates back 3,500 years to its first mention in 1479 BCE by Thutmose II, whose ancient Egyptian records mention it as a centre for production of indigo dye. Sargon II also makes mention of it as Suginin.

Sakhnin is situated on an ancient site, where remains from columns and cisterns have been found.[4] It was mentioned as Sogane, a town fortified in 66, by Josephus.[5] A cistern, excavated near the mosque in the old city centre, revealed pottery fragments dating from the 1st to the 5th century CE.[6]

In the Crusader era, it was known as Zecanin.[7] In 1174 it was one of the casales (villages) given to Phillipe le Rous.[8] In 1236 descendants of Phillipe le Rous confirmed the sale of the fief of Saknin.[9]

Ottoman era

In 1596, Sakhnin appeared in Ottoman tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Akka of the Liwa of Safad. It had a population of 66 households and 8 bachelors, all Muslim. It paid taxes on wheat, barley, olives, cotton, and a water mill.[10][11]

In 1859 the British Consul Rogers estimated the population to be 1,100, and the cultivated area 100 feddans,[12] while in 1875 Victor Guérin found 700 inhabitant, both Muslims, Greek Orthodox and ”Schismatic Greek".[13]

In 1881, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described Sakhnin as follows: "A large village of stone and mud, amid fine olive-groves, with a small mosque. The water supply is from a large pool about half a mile to the south-east. The inhabitants are Moslems and Christians".[14]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Sakhnin had about 1,915 inhabitants; 1,640 Muslims, 150 Catholic Christians and 125 Greek Christians.[15]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Sakhnin had a population of 1,575; 1,367 Muslims and 208 Christians;[16] 87 Orthodox and 121 Greek Catholic (Melchite).[17] The population increased in the 1931 census to a total of 1,891; 1688 Muslims, 202 Christians, and 1 Jew, in a total of 400 houses.[18]

By 1945, Sakhnin had 2,600 inhabitants; 2310 Muslims and 290 Christians.[19] The total jurisdiction of the village was 70,192 dunams of land.[20] 3,622 dunams were used for plantations and irrigable land, 29,366 dunams for cereals,[21] while 169 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[22]

State of Israel

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Sakhnin surrendered to Israeli forces on July 18, 1948, during Operation Dekel, but was re-captured by Arab forces shortly afterwards. It finally fell without battle during Operation Hiram, 29–31 October 1948. Many of the inhabitants fled north but some stayed and were not expelled by the Israeli soldiers.[23] The town remained under Martial Law until 1966.

In 1976, it became the site of the first Land Day marches, in which six Israeli Arabs were killed by Israeli forces during violent protests of government confiscation of 5,000 acres (20 km2) of Arab-owned land near Sakhnin. And in 1976 three more civilians were killed during clashes with the police, and in Jerusalem and the Aqsa Intifada in 2000 two men were killed.

Sports

In 2003, the town's football club, Bnei Sakhnin, became one of the first Arab teams to play in the Israeli Premier League, the top tier of Israeli football.[24] The following year, the club won the State Cup, and was the first Arab team to do so; consequently, it participated in the UEFA Cup the following season, losing out to Newcastle United. The team received a new home with the 2005 opening of Doha Stadium, funded by the Israeli government and the Qatar National Olympic Committee, whose capital it is named after. The stadium has a capacity of 5,000.[24]

Sakhnin is also the hometown of Abbas Suan, an Israeli international footballer who previously played for Bnei Sakhnin. The town and their soccer team are the subject of the 2010 documentary film After The Cup: Sons of Sakhnin United[25]

On 19 September 2008, Bnei Sakhnin played a game with the Spanish team Deportivo de La Coruña.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 116

- ↑ סח'נין 2014

- ↑ Dauphin, 1998, pp. 663-664

- ↑ Tsafrir et al, 1994, p. 235

- ↑ Tahan, 2005, Sakhnin

- ↑ Frankel, 1988, p. 255

- ↑ Strehlke, 1869, p. 8, No. 7; cited in Röhricht, 1893, RHH, p. 137, No. 517; cited in Ellenblum, 2003, p. 109, note 16 and Frankel, 1988, p. 255

- ↑ Strehlke, 1869, p. 64, No.81; cited Röhricht, 1893, RHH, p. 269, No. 1069; cited in Frankel, 1988, p. 265

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 191

- ↑ Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 writes that the Safad register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 286

- ↑ Guérin, 1880, pp. 469- 471

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, pp. 285–286

- ↑ Schumacher, 1888, p. 174

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Acre, p.37

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 50

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 102

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 4

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 41

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 81

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 131

- ↑ Morris, 1987, p. 226

- 1 2 Soccer: In Israel and Italy, storied teams rise International Herald Tribune, 15 April 2007

- ↑ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1616504/

- ↑ El Deportivo de La Coruña vuelve a Europa EL PAÍS, 26 July 2008

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C. R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Ellenblum, Ronnie (2003). Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521521871.

- Frankel, Rafael (1988). "Topographical notes on the territory of Acre in the Crusader period". Israel Exploration Journal. 38 (4): 249–272.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (1987). The Birth of the Palestinian refugee problem, 1947-1949. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33028-9.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century. Columbia University.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Strehlke, E., ed. (1869). Tabulae Ordinis Theutonici ex tabularii regii Berolinensis codice potissimum. Berlin: Weidmanns.

- Tahan, Hagit (2005-12-29). "Sakhnin" (117). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Tsafrir, Y.; Leah Di Segni; Judith Green (1994). (TIR): Tabula Imperii Romani: Judaea, Palaestina. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. ISBN 965-208-107-8.

External links

- Sakhnin municipality site

- Welcome To Sakhnin

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 5: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- 'Not quite Zurich' Eretz magazine