Ceuta

| Ceuta | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous city | |||

| |||

.svg.png) Location of Ceuta within Spain | |||

| Coordinates: 35°53′18″N 5°18′56″W / 35.88833°N 5.31556°WCoordinates: 35°53′18″N 5°18′56″W / 35.88833°N 5.31556°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Autonomous city | Ceuta | ||

| First settled | 5th century BC | ||

| End of Muslim rule | 14 August 1415 | ||

| Ceded to Spain | 1 January 1668 | ||

| Autonomy status | 14 March 1995 | ||

| Founded by | Carthaginians | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Autonomous city | ||

| • Body | Council of Government | ||

| • Mayor-President | Juan Jesús Vivas (PP) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 18.5 km2 (7.1 sq mi) | ||

| • Land | 18.5 km2 (7.1 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) | ||

| Highest elevation | 349 m (1,145 ft) | ||

| Population (2011)[1] | |||

| • Total | 82,376 | ||

| • Density | 4,500/km2 (12,000/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) |

Ceutan ceutí (es) | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | ES-CE | ||

| Postal code | 51001–51005 | ||

| Official language | Spanish | ||

| Parliament | Cortes Generales | ||

| Congress | 1 deputy (out of 350) | ||

| Senate | 2 senators (out of 264) | ||

| Website | Ceuta.es | ||

Ceuta (/ˈsjuːtə,

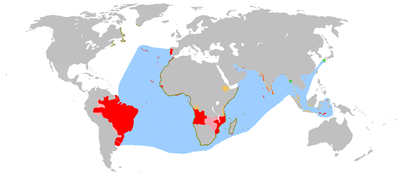

Ceuta, like Melilla and the Canary Islands, was a free port before Spain joined the European Union.[3] As of 2011, it has a population of 82,376.[1] Its population consists of Christians, Muslims and small minorities of Sephardic Jews and ethnic Sindhi Hindus.

Spanish is the official language, while Darija Arabic is also spoken by 40–50% of the population, which is of Moroccan origin.[4][5]

History

.jpg)

Ceuta's location has made it an important commercial trade and military way-point for many cultures, beginning with the Carthaginians in the 5th century BC, who called the city Abyla; initially, this was also its name in Greek and Latin. It was known variously in Ancient Greek as: Ἀβύλη, Ἀβύλα, Ἀβλύξ, or Ἀβίλη στήλη (Abyle-Latn, Abila-Latn, Ablyx or Abile Stele, "Pillar of Abyle")[6] and in the Latin derivation from Greek as Abyla Mons Columna ("Mount Abyla" or "Column of Abyla"). Together with Gibraltar on the European side, it formed one of the famous "Pillars of Hercules".[6][7] Later, it was renamed for a formation of seven surrounding smaller mountains, collectively referred to as Septem Fratres ('[The] Seven Brothers') by Pomponius Mela, which lent their name to a Roman fortification known as Castellum ad Septem Fratres.[6]

It changed hands again approximately 400 years later, when Vandal tribes ousted the Romans. After being controlled by the Visigoths, it then became an outpost of the Byzantine Empire. Ceuta was an important Christian center since the fourth century (as recent discovered ruins of a Roman basilica show[8]).

In the 7th century the Umayyads tried to conquer the region but were unsuccessful. Byzantine governor Julian (described as King of the Ghomara), who was a vassal of the Visigothic kings of Iberia, changed his allegiance after the king Roderic raped his daughter, and exhorted the Muslims to invade the Iberian Peninsula. Under the leadership of the Berber general Tariq ibn Ziyad, the Muslims used Ceuta as a staging ground for an assault on the Visigothic Iberian Peninsula. After Julian's death, the Berbers took direct control of the city, which the indigenous Berber tribes resented. They destroyed Ceuta during the Kharijite rebellion led by Maysara al-Matghari in 740.

Ceuta lay in ruins until it was resettled in the 9th century by Mâjakas, chief of the Majkasa Berber tribe, who started the short-lived Banu Isam dynasty.[9] His great-grandson briefly allied his tribe with the Idrisids, but the Banu Isam rule ended in 931 when he abdicated in favor of Abd ar-Rahman III, the Umayyad Caliph of Cordoba. Ceuta reverted to Moorish Andalusian rule in 927 along with Melilla, and later Tangier, in 951.

Chaos ensued with the fall of the Umayyad caliphate in 1031. Following this Ceuta and the rest of Muslim Iberia were controlled by successive North African dynasties. Starting in 1084, the Almoravid Berbers ruled the region until 1147, when the Almohads conquered the land. Apart from Ibn Hud's rebellion of 1232, they ruled until the Tunisian Hafsids established control. The Hafsids' influence in the west rapidly waned, and Ceuta's inhabitants eventually expelled them in 1249. After this, a period of political instability persisted, under competing interests from the Kingdom of Fez and the Kingdom of Granada. The Kingdom of Fez finally conquered the region in 1387, with assistance from the Crown of Aragon.

15th to 16th century

.jpg)

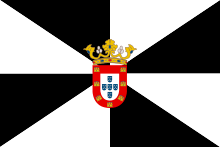

On the morning of 21 August 1415, king John I of Portugal led his sons and their assembled forces in a surprise assault that would come to be known as the Conquest of Ceuta. The battle was almost anti-climactic, because the 45,000 men who traveled on 200 Portuguese ships caught the defenders of Ceuta off guard and only suffered eight casualties. By nightfall the town was captured. On the morning of August 22, Ceuta was in Portuguese hands. Álvaro Vaz de Almada, 1st Count of Avranches was asked to hoist what was to become the flag of Ceuta, which is identical to the flag of Lisbon, but in which the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Portugal was added to the center; the original Portuguese flag and coat of arms of Ceuta remained unchanged, and the modern-day Ceuta flag features the configuration of the Portuguese shield.

John's son Henry the Navigator distinguished himself in the battle, being wounded during the conquest. The looting of the city proved to be less profitable than expected for John I; he decided to keep the city to pursue further enterprises in the area.[10]

From 1415 to 1437 Pedro de Meneses, 1st Count of Vila Real became the first governor of Ceuta.

The Benemerine sultan started the Siege of Ceuta (1418) but was defeated by the first governor of Ceuta before reinforcements arrived in the form of John, Constable of Portugal and his brother Henry the Navigator who were sent with troops to defend Ceuta.

Under King John I of Portugals son, Duarte, the colony at Ceuta rapidly became a drain on the Portuguese treasury. Trans-Saharan trade journeyed instead to Tangier. It was soon realised that without the city of Tangier, possession of Ceuta was worthless. In 1437, Duarte's brothers Henry the Navigator and Fernando, the Saint Prince persuaded him to launch an attack on the Marinid sultanate. The resulting Battle of Tangier (1437), led by Henry, was a debacle. In the resulting treaty, Henry promised to deliver Ceuta back to the Marinids in return for allowing the Portuguese army to depart unmolested, which he reneged on.

Possession of Ceuta would indirectly lead to further Portuguese expansion. The main area of Portuguese expansion, at this time, was the coast of Magreb, where there was grain, cattle, sugar, and textiles, as well as fish, hides, wax, and honey.[11]

Ceuta had to endure alone for 43 years, until the position of the city was consolidated with the taking of Ksar es-Seghir (1458), Arzila and Tangier (1471) by the Portuguese.

The city was recognized as a Portuguese possession by the Treaty of Alcáçovas (1479) and by the Treaty of Tordesilhas (1494).

In the 1540s the Portuguese began building the Royal Walls of Ceuta as they are today including bastions, a navigable moat and a drawbridge. Some of these bastions are still standing, like the bastions of Coraza Alta, Bandera and Mallorquines.[12]

Luís de Camões lived in Ceuta between 1549 and 1551, losing his right eye in battle, which influenced his work of poetry Os Lusíadas.

In 1578 King Sebastian of Portugal died at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir (known as the Battle of Three Kings) in what is today northern Morocco, without descendants, triggering the 1580 Portuguese succession crisis. His granduncle, the elderly Cardinal Henry, succeeded him as King, but Henry also had no descendants, having taken holy orders. When the cardinal-king died two years after Sebastian's disappearance, three grandchildren of King Manuel I of Portugal claimed the throne: Infanta Catarina, Duchess of Braganza, António, Prior of Crato, and Philip II of Spain (Uncle of former King Sebastian of Portugal), who would go on to be crowned King Philip I of Portugal in 1581, uniting the two crowns and overseas empires known as the Iberian Union,[13] which allowed the two kingdoms to continue without being merged.

17th to 19th century

During the Iberian Union 1580 to 1640, Ceuta attracted many residents of Spanish origin.[14] Ceuta became the only city of the Portuguese Empire that sided with Spain when Portugal regained its independence in the Portuguese Restoration War of 1640.

On 1 January 1668 by the Treaty of Lisbon, King Afonso VI of Portugal recognized the formal allegiance of Ceuta to Spain and formally ceded Ceuta to King Carlos II of Spain.

The city was attacked by Moroccan forces under Moulay Ismail during the Siege of Ceuta (1694-1727). During the longest siege in history, the city underwent changes leading to the loss of its Portuguese character. While most of the military operations took place around the Royal Walls of Ceuta, there were also small-scale penetrations by Spanish forces at various points on the Moroccan coast, and seizure of shipping in the Strait of Gibraltar.

Disagreements regarding the border of Ceuta resulted in the Hispano-Moroccan War (1859–60), which ended at the Battle of Tetuán.

20th to 21st century

In July 1936, General Francisco Franco took command of the Spanish Army of Africa and rebelled against the Spanish republican government; his military uprising led to the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939. Franco transported troops to mainland Spain in an airlift using transport aircraft supplied by Germany and Italy. Ceuta became one of the first casualties of the uprising: General Franco's rebel nationalist forces seized Ceuta, while at the same time the city came under fire from the air and sea forces of the official republican government.[15]

The Llano Amarillo monument was erected to honor Francisco Franco, it was inaugurated on 13 July 1940. The tall obelisk has since been abandoned, but the shield symbols of the Falange and Imperial Eagle remain visible.[16]

When Spain recognized the independence of Spanish Morocco in 1956, Ceuta and the other plazas de soberanía remained under Spanish rule. Spain considered them integral parts of the Spanish state, but Morocco has disputed this point.

Culturally, modern Ceuta is part of the Spanish region of Andalusia. It was attached to the province of Cádiz until 1925, the Spanish coast being only 20 km (12.5 miles) away. It is a cosmopolitan city, with a large ethnic Arab Muslim minority as well as Sephardic Jewish and Hindu minorities.[17]

On 5 November 2007, King Juan Carlos I visited the city, sparking great enthusiasm from the local population and protests from the Moroccan government.[18] It was the first time a Spanish head of state had visited Ceuta in 80 years.

Since 2010, Ceuta (and Melilla) have declared the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha or Feast of the Sacrifice, as an official public holiday. It is the first time a non-Christian religious festival has been officially celebrated in Spain since the Reconquista.[19][20]

Ecclesiastical history

The Catholic Diocese of Ceuta existed from 1417 to 1879. It was a suffragan of the Patriarchate of Lisbon until 1675 and the end of the Iberian Union, when Ceuta chose to remain linked to the king of Spain. Since then it has been a suffragan of the archbishopric of Seville.[21] The Diocese of Tanger was suppressed and incorporated to that of Ceuta in 1570.[22]

In 1851, upon the signature of the concordat between the Holy See and Spain, the diocese of Ceuta was agreed to be suppressed, being combined into the Diocese of Cádiz y Ceuta.[23] Until then in the Diocese of Cádiz y Algeciras, the bishop was usually the apostolic administrator of Ceuta. The agreement was not implemented until 1879.

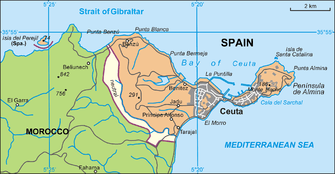

Geography

Ceuta is dominated by Monte Anyera, a hill along its western frontier with Morocco. The mountain is guarded by a military fort.

Monte Hacho on the Peninsula of Almina overlooking the port is one of the possible locations for the southern pillar of the Pillars of Hercules of Greek legend (the other possibility being Jebel Musa).[24]

Climate

Ceuta has a maritime-influenced Subtropical/Mediterranean climate, similar to nearby Spanish and Moroccan cities such as Tarifa, Algeciras or Tangiers.[25] The average diurnal temperature variation is relatively low; the average annual temperature is 18.8 °C (65.8 °F) with average yearly highs of 21.4 °C (70.5 °F) and lows of 15.7 °C (60.3 °F) though the Ceuta weather station has only been in operation since 2003.[26] Ceuta has relatively mild winters for the latitude, while summers are warm yet milder than in the interior of Southern Spain, due to the moderating effect of the Straits of Gibraltar. Summers are very dry, but yearly precipitation is still at 849 millimetres (33.4 in),[26] which could be considered a humid climate if the summers were not so arid.

| Climate data for Ceuta city (1m altitude) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.7 (71.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

33.7 (92.7) |

35.3 (95.5) |

40.2 (104.4) |

38.9 (102) |

34.8 (94.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

27.2 (81) |

25.6 (78.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61) |

16.7 (62.1) |

17.8 (64) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.9 (84) |

28.5 (83.3) |

26.1 (79) |

22.9 (73.2) |

18.9 (66) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

15.0 (59) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.0 (77) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.1 (52) |

11.6 (52.9) |

12.2 (54) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.1 (70) |

21.7 (71.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

12.2 (54) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.2 (45) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

12.2 (54) |

7.4 (45.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 122 (4.8) |

145 (5.71) |

90 (3.54) |

57 (2.24) |

21 (0.83) |

3 (0.12) |

1 (0.04) |

3 (0.12) |

37 (1.46) |

82 (3.23) |

127 (5) |

161 (6.34) |

849 (33.43) |

| Average precipitation days | 7 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 54 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 75 | 68 | 71 | 66 | 67 | 61 | 70 | 72 | 75 | 73 | 73 | 70 |

| Source: Weather.com,[27] WorldWeatherOnline,[28][26] and Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[29] | |||||||||||||

Politics

Since 1995, Ceuta is, along with Melilla, one of the two autonomous cities of Spain.[30]

Ceuta is known officially in Spanish as Ciudad Autónoma de Ceuta (English: Autonomous City of Ceuta), with a rank between a standard Spanish city and an autonomous community. Ceuta is part of the territory of the European Union. The city was a free port before Spain joined the European Union in 1986. Now it has a low-tax system within the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union. As of 2006, its population was 75,861.

Ceuta has held elections every four years since 1979, for its 25-seat assembly. The leader of its government was the Mayor until the Autonomy Statute had the title changed to the Mayor-President. As of 2011, the People's Party (PP) won 18 seats, keeping Juan Jesús Vivas as Mayor-President, which he has been since 2001. The remaining seats are held by the regionalist Caballas Coalition (4) and the Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE, 3).[31]

Due to its small population, Ceuta elects only one member of the Congress of Deputies, the lower house of the Spanish legislature. As of 2011 election, this post is held by Francisco Márquez de la Rubia of the PP.[32]

Subdivisions

Ceuta is subdivided into 63 barriadas (neighbourhoods), such as Barriada de Berizu, Barriada de P. Alfonso, Barriada del Sarchal, and El Hacho.[33][34][35]

Dispute with Morocco

The government of Morocco has repeatedly called for Spain to transfer the sovereignty of Ceuta and Melilla, together with the rest of the Spanish plazas de soberanía on the North African coast, on the grounds of asserting its territorial integrity. Morocco has claimed the territories are colonies.[36]

Economy

The official currency of Ceuta is the euro. It is part of a special low tax zone in Spain.[37] Ceuta is one of two Spanish port cities on the northern shore of Africa, along with Melilla. They are historically military strongholds, free ports, oil ports, and also fishing ports.[38] Today the economy of the city depends heavily on its port (now in expansion) and its industrial and retail centres.[37] Ceuta Heliport is now used to connect the city to mainland Spain by air. Lidl, Decathlon Group and El Corte Inglés (hardware) have branches in Ceuta. There is also a casino. Border trade between Ceuta and Morocco is active because of advantage of tax-free status. Thousands of Moroccan women are involved in porter trade daily. Moroccan dirham is actually used in such trade, despite the fact that prices are marked in euro.[39] [40][41]

Transport

The city receives high numbers of ferries each day from Algeciras in Andalusia in the south of Spain, along with Melilla and the Canary Islands. The closest airport is Sania Ramel Airport in Morocco. There is a bus service throughout the city which does not pass into neighbouring Morocco.

A single road border checkpoint allows for cars to travel between Morocco and Ceuta. The rest of the border is closed and inaccessible.

Demographics

Due to its location, Ceuta is home to a mixed ethnic and religious population. The two main religious groups are Christians and Muslims. As of 2006 approximately 50% of the population was Christian and approximately 49% Muslim.[42] However, by 2012, the portion of Ceuta's population that identify as Roman Catholic was 68.0%, while the portion of Ceuta's population that identify as Muslim was 28.3%.[43]

Spanish is the primary and official language of the enclave.[44] Moroccan Arabic is widely spoken,[45] as are Berber and French.[46]

Religion

Christianity has been present in Ceuta (called in Roman times Septem[47] or Septum[48]) continuously since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The ruins of a basilica in downtown Ceuta confirm this reality.[49]

In 1415, on conquering the city from the Muslims, the Portuguese started the construction of the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Ceuta was established two years later, and in 1851 was merged into the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cadiz y Ceuta. The present cathedral, dating from the late 17th century, combines baroque and neoclassical elements.

Education

The University of Granada offers undergraduate programs at their campus in Ceuta. Like all areas of Spain, Ceuta is also served by the National University of Distance Education (UNED).

Primary and secondary education is possible only in Spanish however a growing number of schools are entering the Bilingual Education Program.

Migrants

As in Melilla, Ceuta is attractive to migrants who try to use it as an entry to Europe. As a result the enclave is surrounded by double fences that are 6 meters high and hundreds of migrants congregate near the fences waiting for a chance to cross them. The fences are regularly stormed by migrants trying to claim asylum once they enter Ceuta.[50]

Notable people from Ceuta

1083 to 1700

- Qadi Ayyad (1083 in Ceuta – 1149) born in Ceuta, then belonging to the Almoravids was the great imam of that city

- Al-Idrisi (1100 in Ceuta – 1165 in Ceuta) was an Arab Muslim geographer, cartographer and Egyptologist. He lived in Palermo at the court of King Roger II of Sicily, known for the "Tabula Rogeriana"

- Abu al-Abbas as-Sabti (Ceuta 1129 - Marrakesh 1204) is the patron saint of Marrakesh

- Joseph ben Judah of Ceuta (c. 1160–1226) was a Jewish physician and poet, and disciple of Moses Maimonides

- Abu al-Abbas al-Azafi (1162 in Ceuta – 1236) a religious and legal scholar, member of the Banu al-Azafi who ruled Ceuta

- Mohammed ibn Rushayd (1259 in Sabta – 1321) was a judge, writer and scholar of Hadith

- Álvaro of Braganza ( 1440 - 1504) was a president of Council of Castile.

1700 to 1800

- George Camocke (1666-1732) was a Royal Navy captain and former admiral for Spain who was exiled to Ceuta to live out the last years of his life.

- Don Fernando de Leyba (1734 in Ceuta - 1780) was a Spanish officer who served as the third governor of Upper Louisiana from 1778 until his death.

- Brigadier General Francisco Antonio García Carrasco Díaz (1742 in Ceuta – 1813 in Lima, Peru ) was a Spanish soldier and Royal Governor of Chile

- Sebastián Kindelán y O'Regan (1757 in Ceuta – 1826 Santiago de Cuba) was a colonel in the Spanish Army who served as governor of East Florida 1812/1815, of Santo Domingo 1818/1821 and was provisional governor of Cuba 1822/1823

- Isidro de Alaix Fábregas Count of Vergara and Viscount of Villarrobledo, (1790 in Ceuta – 1853 in Madrid) was a Spanish general of the First Carlist War who backed Isabella II of Spain

1800 to 1950

- General Francisco Llano de la Encomienda (1879 in Ceuta – 1963 in Mexico City) was a Spanish soldier. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–39) he remained loyal to the Second Spanish Republic

- General Antonio Escobar Huertas (1879 in Ceuta – executed 1940 in Barcelona) was a Spanish military officer

- África de las Heras Gavilán (Ceuta, 1909 – Moscow, 1988) was a Spanish Communist, naturalized Soviet citizen, and KGB spy who went by the code name Patria

- Eugenio Martín (born 1925 in Ceuta) is a Spanish film director and screenwriter

- Jacob Hassan, PhD (1936 in Ceuta – 2006 in Madrid) was a Spanish-Jewish philologist

- José Martínez Sánchez (born 1945 in Ceuta), nicknamed Pirri, is a retired Spanish footballer, mainly played for Real Madrid, appearing in 561 competitive games and scoring 172 goals

- Manuel Chaves González (born 1945 in Ceuta) is a Spanish politician of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party. He served as the Third Vice President of the Spanish Government from 2009 to 2011

- Ramón Castellano de Torres (born 1947 in Ceuta) is a Spanish artist, thought by some to be an expressionist painter

- José Ramón López (1950) was a sprint canoer. He won the silver medal in the 1976 Summer Olympics.

1950 to date

- Miguel Bernardo Bianquetti (born 1951 in Ceuta), known as Migueli is a Spanish retired footballer who played central defender.

- Francisco Lesmes and Rafael Lesmes Bobed brothers and Spanish footballers.

- Ignacio Velázquez Rivera (born 1953), first Mayor-President of Melilla

- Juan Jesús Vivas Lara (Ceuta 1953) became the Mayor-President of Ceuta in Spain in 2001

- Pedro Aviles Gutiérrez (Ceuta, 1956) is a Spanish novelist from Madrid.

- Nayim (Ceuta, 1966) is a retired Spanish footballer; he scored a last-minute goal for Real Zaragoza in the 1995 UEFA Cup Winners' Cup Final.

- Eva María Isanta Foncuberta (born 1971 in Ceuta) is a Spanish actress [51]

- Mohamed Taieb Ahmed (1975, Ceuta) is a Spanish-Moroccan drug lord [52] responsible for trafficking hashish across the Strait of Gibraltar and into Spain.

- Lorena Miranda (Ceuta, 1991) is a Spanish female water polo player. She won the silver medal in Water polo at the 2012 Summer Olympics.

Twin towns and sister cities

Ceuta is twinned with:

See also

- AD Ceuta, former football club

- Arab Baths in Ceuta

- Benzú

- Hotel Tryp Ceuta

- Ceuta border fence

- Ceuta and Melilla (disambiguation)

- Plazas de soberanía – Spanish exclaves on the Moroccan coast

- Porteadoras – mule ladies, bale workers

- Royal Walls of Ceuta

- Spanish Morocco

References

- 1 2 "Decision Spain >> Resources >> Municipalities without testimony >> Ceuta + Melilla". Decision Espana. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Ceuta. Oxford Dictionaries.

- ↑ Ferrer-Gallardo, Xavier. "The Spanish–Moroccan border complex: Processes of geopolitical, functional and symbolic rebordering". Political Geography. 27 (3): 301–321. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.12.004.

- ↑ Verónica Rivera (December 2006). "IMPORTANCIA Y VALORACIÓN SOCIOLINGÜÍSTICA DEL DARIJA EN EL CONTEXTO DE LA EDUCACIÓN SECUNDARIA PÚBLICA EN CEUTA" [Importance and Socio-Linguistic Valuation of Darija in the Context of Public Secondary Education in Ceuta]. REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA DE ESTUDIOS FILOLÓGICOS (in Spanish) (12). ISSN 1577-6921.

- ↑ Fernández García, Alicia (2016). "Nacionalismo y representaciones lingüísticas en Ceuta y en Melilla". Revista de Filología Románica. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. 33 (1): 23–46. doi:10.5209/RFRM.55230. ISSN 0212-999X.

- 1 2 3 Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, illustrated by numerous engravings on wood. William Smith, LLD (London:Walton and Maberly, Upper Gower Street and Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row; John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1854), Abyla )

- ↑ A Latin Dictionary. Founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. revised, enlarged, and in great part rewritten by. Charlton T. Lewis, Ph.D. and. Charles Short, LL.D. (Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1879), "Abyla"

- ↑ Publiceuta. "Basílica Tardorromana de Ceuta. Guía turística de Ceuta". www.ceutaturistica.com. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Bernard Lewis; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1994). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 690. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ López de Coca Castañer, José Enrique (1998). "Granada y la expansión portuguesa en el Magreb extremo". Historia. Instituciones. Documentos. Seville: Universidad de Sevilla (25): 351. ISSN 0210-7716.

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G., A History of Spain and Portugal, Vol.1, Chap.10 "The Expansion"

- ↑ "Ceuta". fortified-places.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑

- Kamen, Henry (1999). Philip of Spain. Yale University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780300078008.

- ↑ Griffin, H (2010). Ceuta Mini Guide. Mirage. ISBN 978-0-9543335-3-9.

- ↑ "History of Ceuta". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ↑ "Franco monument now part of a rubbish dump in Ceuta". Archived from the original on 7 December 2012.

- ↑ "Resistir en el monte del Renegado". El País. 22 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ "Ceuta y Melilla son España, dice Juan Carlos I; Sebta y Melilia son nuestras, responde Mohamed VI". Blogs.periodistadigital.com. 22 February 1999. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ "Muslim Holiday in Ceuta and Melilla". Spainforvisitors.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "Public Holidays and Bank Holidays for Spain". Qppstudio.net. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "Diocese of Ceuta". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Tingis". Newadvent.org. 1 July 1912. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Cadiz". Newadvent.org. 1 November 1908. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ↑ H. Micheal Tarver, Emily Slape, eds. (25 July 2016). The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. I. ABC-CLIO. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-61069-422-3.

- ↑ "Ceuta, Spain — Climate Summary". weatherbase. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Valores climatológicos normales. Ceuta" [Normal climate values. Ceuta]. AEMET (in Spanish). Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Ceuta, Spain". Weather.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Ceuta Monthly Climate Averages". World Weather Online. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Valores extremos. Ceuta — Selector" [Extreme values. Ceuta - Selector]. AEMET (in Spanish). Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Ley Orgánica 1/1995, de 13 de marzo, Estatuto de Autonomía de Ceuta". Noticias.juridicas.com. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ "Resultados Electorales en Ceuta: Elecciones Municipales 2011 en EL PAÍS" (in Spanish). EDICIONES EL PAÍS S.L. 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Congress / Listing of Members by electoral district". Congreso de los Diputados (in Spanish). 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "El servicio de Policia de Barriadas podria funcionar a partir del 15 de septiembre" [The Police Service of Barriadas could work from September 15]. El Pueblo de Ceuta (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ "Map of Ceuta". planetware.

- ↑ "Códigos postales de Ceuta en Ceuta". Codigo-postal.info. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ Gold, Peter (2000). Europe or Africa? A contemporary study of the Spanish North African enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. Liverpool University Press. pp. XII–XIII. ISBN 0-85323-985-1.

- 1 2 "Economic Data of Ceuta, de ceutna digital". Ceuta.es. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- ↑ O'Reilly, Gerry; O'Reilly, J. G. (1994). IBRU, Boundary and Territory Briefing. Ceuta and the Spanish Sovereign Territories: Spanish and Moroccan. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9781897643068. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ↑ "Morocco 'mule women' in back-breaking trade from Spain enclave". 2017-10-06. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "The economics of exclaves". 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Moroccan women used as 'mules' to avoid tariffs | DW | 11.05.2018". DW.COM. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ Roa, J. M. (2006). "Scholastic achievement and the diglossic situation in a sample of primary-school students in Ceuta". Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa. 8 (1).

- ↑ "Interactivo: Creencias y prácticas religiosas en España". lavanguardia.com. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Languages Across Europe – Spanish". BBC. 2014-10-14. Archived from the original on 2018-04-05.

- ↑ Sayahi, Lotfi (2011). "Spanish in Contact with Arabic". In Díaz-Campos, Manuel. The Handbook of Hispanic Sociolinguistics. Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 476–477. ISBN 978-1-4051-9500-3.

- ↑ Roa-Venegas, José María (2006). "Scholastic Achievement and the Diglossic Situation in a Sample of Primary-School Students in Ceuta". Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa. 8 (1): 3, 12 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ Walter E. Kaegi (4 November 2010). Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- ↑ A Cyclopædia of Biblical Literature. 2. John Kitto, William Lindsay Alexander. 1864. p. 350.

- ↑ Villada, Fernando. "Ceuta huellas del cristianismo en Ceuta". academia.edu. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Hundreds of migrants storm fence to reach Spanish enclave of Ceuta". BBC. 17 February 2017.

- ↑ IMDb retrieved 19 October 2017

- ↑ "Vuelve 'El Nene'". Interviu. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ceuta. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ceuta. |

- (in Spanish) Official Ceuta government website

- www.ceuta.si Ceuta tourism website

- Web Oficial Servicios Turísticos de Ceuta

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)