Leptis Parva

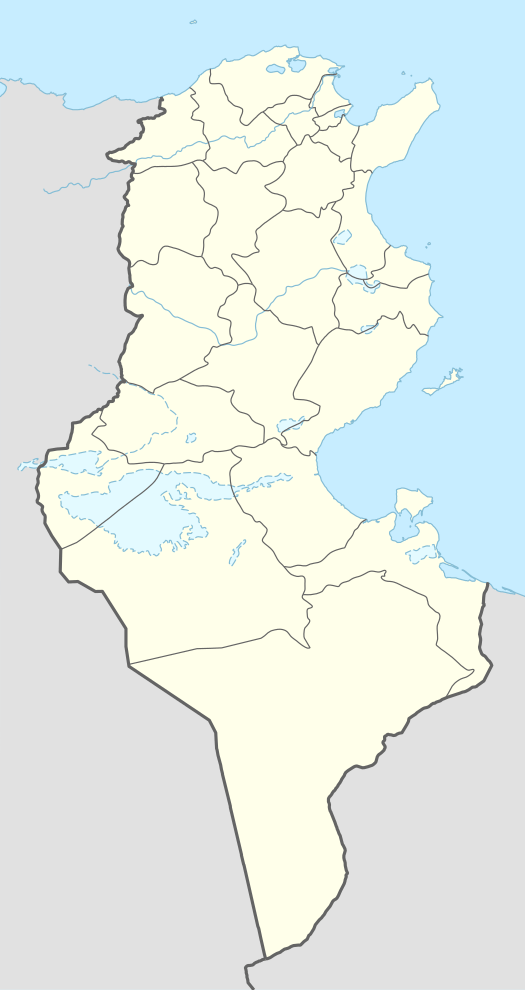

Shown within Tunisia | |

| Alternative name | Leptis Minor, Leptis Parva, Leptiminus |

|---|---|

| Location | Tunisia |

| Region | Monastir Governorate |

| Coordinates | 35°40′40″N 10°52′00″E / 35.67778°N 10.86667°ECoordinates: 35°40′40″N 10°52′00″E / 35.67778°N 10.86667°E |

Leptis or Lepcis, known by later writers as Leptis Minor, Leptis Parva or Leptiminus, to distinguish it from Leptis Magna, was a Phoenician colony founded on the African coast between Hadrumetum and Thapsus on the Sinus Neapolitanus, just south of the modern city of Monastir, Tunisia. Leptis was one of the wealthiest cities in the region, and flourished both under Carthage and in Roman times.[1]

History

Like other Phoenician cities on the African coast, Leptis was originally a colony of Tyre, although in historic times it paid tribute to Carthage.[1][2] The name Leptis signified a naval station in the Phoenician language, indicating that it was probably established as a waypost between other colonies.[1] It was located in the fertile coastal district of Emporia, in the region of Byzacium, the later Roman province of Byzacena.[3][4] For most of its history it was known simply as Leptis or Lepcis, but later writers term it Leptis Minor, Leptis Parva, or Leptiminus to distinguish it from Leptis Magna in Tripolitania.[1]

Early history

Leptis is first mentioned in the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, written in the middle or latter part of the fourth century BC, as one of the cities in the country of the lotus-eaters.[5] After the First Punic War, Leptis was at the center of the Mercenary War, a revolt of the Carthaginian mercenaries led by Mathos, which was only suppressed through the coöperation of Hamilcar Barca and Hanno the Great in 238 BC.[6] At the time of the Second Punic War, Leptis was one of the wealthiest cities of Emporia, paying Carthage a tribute equivalent to one Attic talent, roughly fifty-seven pounds or twenty-six kilograms of silver, per day.[7]

It was at Leptis that Hannibal's army disembarked on their return to Africa in 203 BC.[8] In the following year, Leptis was one of few cities in north Africa of which the Romans had yet gained control, and from which they were able to draw supplies, the rest of Africa still remaining under the control of the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal.[9]

Following the conclusion of the war in 201 BC, Emporia was overrun by Masinissa, who claimed the district by ancient right, and the Carthaginians appealed to Rome for adjudication of the matter, as they were obliged to do by the treaty ending the war. The senate appointed a commission to look into the matter, including Scipio Africanus, the conqueror of Carthage. Although Scipio was uniquely positioned to resolve the dispute, the commission left the rightful possession of Emporia undecided, and Masinissa was able to organize much of the territory into the kingdom of Numidia, although Leptis itself remained unconquered.[7]

Roman period

The region around Leptis came under Roman control following the Third Punic War in 146 BC. In Roman times, Leptis was a civitas libera, or free city, with its own autonomous government.[3] Based on coins bearing the name of Leptis, it has been conjectured that a Roman colony might have been established at Leptis in later times; but it is uncertain whether these coins refer to Leptis Minor or Leptis Magna, and in any case some free cities minted their own coinage.[1]

The possession of Leptis became an important matter during the Civil War. In 49 BC, Juba I of Numidia was at war with the Leptitani when the war was first carried over into Africa. Juba had long been an ally of Pompeius, and opposed to Caesar, but Caesar's lieutenant, Gaius Scribonius Curio, deemed it safe to attack Utica, as Juba had left his own lieutenant, Sabura, in charge of the countryside around Utica. Curio routed a Numidian force with a night-time cavalry raid, but rashly engaged Sabura's main force and was annihilated at Bagradas, as Juba approached from Leptis with reinforcements.[10]

At the beginning of January, 46 BC, Caesar arrived at Leptis, and received a deputation from the city offering its submission. Caesar placed guards on the city gates to prevent his soldiers from entering the city or harassing its people, and sent his cavalry back to their ships to protect the countryside, although the latter were ambushed by a Numidian force. Shortly afterward, Caesar moved his camp to Ruspina, leaving six cohorts at Leptis, under the command of Gaius Hostilius Saserna.[11]

During the winter and spring of 46, Leptis was one of Caesar's primary bases, and a source of provisions. A cavalry troop sent to Leptis for provisions intercepted a force of Numidian and Gaetulian soldiers, whom they took prisoner after a brief skirmish. Part of Caesar's fleet was anchored off Leptis, where they were taken unawares by Publius Attius Varus, one of Pompeius' admirals, who burned Caesar's transports, and captured two undefended quinquiremes. Learning of the attack, Caesar rode to Leptis, and went in pursuit of Varus with his remaining ships, recapturing one of the quinquiremes, along with a trireme. At Hadrumetum, he burned a number of Pompeian transports, and captured or put to flight a number of galleys.[12]

Leptis continued to flourish in imperial times, before Byzacena was ceded to the Vandals in AD 442. The city was retaken by the Byzantine general Belisarius in 533, during the Vandalic War, forming part of the Praetorian Prefecture of Africa, and then the Exarchate of Africa. The city was largely destroyed during the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb in the latter part of the seventh century, although a ribat was built there, probably on the ruins of an earlier Byzantine fortress. The city itself was abandoned, and never resettled.

Bishopric

From the third century until its destruction, Leptis was represented by bishops in various councils of the Roman Catholic Church, including the Councils of Carthage in 256, 411, 484, and 641. The diocese was also involved in the great conflict of African Christianity as Catholic and Donatist bishops for the town appear on the lists of participants in these councils. Among the noted bishops was Laetus, described as a "zelous and very learned man", numbered among those bishops killed by the Vandal king Huneric, after the council of 484.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, vol. II, pp. 161, 162 ("Leptis").

- ↑ Sallust, Bellum Jugurthinum, 19.

- 1 2 Pliny the Elder, v. 4. s. 3.

- ↑ Pomponius Mela, i. 7. § 2.

- ↑ Pseudo-Scylax, Periplus, 110.

- ↑ Polybius, i. 87.

- 1 2 Livy, xxxiv. 62.

- ↑ Livy, xxx. 25.

- ↑ Appian, Bella Punica, xiii. 94.

- ↑ Caesar, De Bello Civili, ii. 37–44.

- ↑ Hirtius, De Bello Africo, 6, 7, 9, 10.

- ↑ Hirtius, De Bello Africo, 61–64.

- ↑ Butler & Burns, Butler's Lives of the Saints: September, p. 41.

Bibliography

- Pseudo-Scylax, Periplus.

- Polybius, Historiae (The Histories).

- Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), Bellum Jugurthinum (The Jugurthine War).

- Gaius Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili (Commentaries on the Civil War).

- Aulus Hirtius (attributed), De Bello Africo (On the African War).

- Titus Livius (Livy), History of Rome.

- Pomponius Mela, De Situ Orbis (On the Places of the World).

- Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder), Historia Naturalis (Natural History).

- Appianus Alexandrinus (Appian), Bella Punica (The Punic Wars).

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, William Smith, ed., Little, Brown and Company, Boston (1854).

- Alban Butler & Paul Burns, Butler's Lives of the Saints: September, A&C Black, (1995).

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)