AirTrain JFK

| AirTrain JFK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | People mover | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Connects JFK International Airport to various points within Queens, New York City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership |

approximately 17,773 paid approximately 27,000 within airport (2014 average) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | December 17, 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Bombardier Transportation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Elevated railway/people mover | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | 32 Bombardier Innovia Metro vehicles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 8.1 miles (13 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Third rail 750 V DC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 60 mph (97 km/h) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AirTrain JFK is an 8.1-mile-long (13 km) elevated people mover system serving the John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City, New York, United States. The system, which operates 24/7 service, consists of three lines and ten stations. It connects the airport's six terminals with the New York City Subway and the Long Island Rail Road in Howard Beach and Jamaica. Bombardier Transportation operates AirTrain JFK under contract with the airport's owner, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

A railroad link to JFK Airport was proposed in 1968 as part of the Program for Action, a wide-ranging proposal to improve transit in the New York metropolitan area. Such a link was not actually constructed for almost three decades because of a lack of funding. From the 1970s to the early 1990s, various plans surfaced to build the JFK Airport railroad line. Meanwhile, the JFK Express subway service and shuttle buses provided an unpopular transport system to and around JFK. In-depth planning for a dedicated transport system at JFK began in 1990. An environmental impact statement for a JFK light-rail system was released in 1997, and construction of the current people-mover system began a year later. During construction, AirTrain JFK encountered several lawsuits, as well as a death during one of the system's test runs. AirTrain JFK opened on December 17, 2003, after several delays.

AirTrain charges a $5 fare for all passengers entering or exiting at either Jamaica or Howard Beach, though passengers traveling within the airport can ride the system for free. The system was originally projected to carry 4 million annual paying passengers and 8.4 million annual inter-terminal passengers every year. However, AirTrain has consistently exceeded ridership projections since opening, and in 2014, the system had 6.4 million paying passengers and 10 million inter-terminal passengers.

History

Context

There have been proposals for a railroad link between Manhattan and JFK Airport since 1968, when the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) proposed an ambitious subway and railroad expansion in the New York City area as part of the Program for Action.[1][2] The plan called for the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) to be extended to JFK Airport along the Van Wyck Expressway.[3] As originally proposed, the LIRR route would have been built during the Program for Action's second phase. It entailed extending the LIRR through the under-construction 63rd Street Tunnel's lower level before turning southward in Manhattan and ending at a new "Metropolitan Transportation Center" below Third Avenue and 48th Street.[1] William J. Ronan—the chairman of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates Newark, LaGuardia, and JFK Airports in the New York City area—proposed bringing the link to Penn Station instead.[4] The site of the proposed Manhattan terminal was moved to 33rd Street, next to Penn Station, in 1969.[5]

Many Rockaway and central Queens residents wanted the link to run along the disused Rockaway Beach Branch, rather than along the Van Wyck, so that Rockaway residents could also use the route to travel to Manhattan quickly.[6] The New York City Board of Estimate approved the revised plan for a link between Penn Station and JFK via the Rockaway Beach Branch in 1969.[7] Later during the planning process, a Woodhaven Junction stop was added along the link's route in response to requests by residents of the Woodhaven neighborhood.[8]

The $210 million LIRR plan faced much criticism, and one section in central Queens attracted heavy opposition. New York State Senator John J. Santucci, representing the Rockaways, raised concerns that a 2,900-foot (880 m) tunnel for the link, which would connect to the Rockaway Beach Branch, would require razing part of Forest Park, a plan his constituents opposed.[9] Santucci said the link's construction would irreversibly destroy part of the park, destroying a community landmark by "stripping away the resources of the people for the luxury of the few".[10] In October 1974, the president of the Hammel Holland Seaside Civic Association wrote to Mayor Abraham Beame, "It is our earnest plea to you that your decision on this rape of Forest Park be rescinded." The association's president added that although it would be cost-ineffective to create a premium service to JFK Airport, the Rockaway Beach Branch should still be reactivated for local passengers.[11]

Ultimately, most of the lines for the Program for Action were canceled altogether due to the New York City fiscal crisis of 1975.[12] In April 1976, Port Authority Chairman Ronan said that the link was "not feasible" due to the economic downturn and a corresponding decrease in air traffic.[4] In 1978, after the Program for Action had been mostly scrapped, independent organizations pushed for the construction of a direct subway link from the IND Rockaway Line south of Aqueduct–North Conduit Avenue.[13] A later study for a dedicated two-lane rapid transit bus line to JFK along the Rockaway Beach Branch, called the "Transitway", was released in 1982. The line would also host taxis, limousines, and vans going to the airport.[14] The Port Authority scrapped the plan the following year in the face of near-unanimous opposition from the communities along the route.[15]

Following the failure of the JFK rail link, the MTA started operating the JFK Express (advertised as "The Train to The Plane"), a premium-fare New York City Subway service that connected Midtown Manhattan to the IND Rockaway Line's Howard Beach–JFK Airport station.[16][17] It ran from 1978 until 1990, transporting passengers to the Howard Beach station.[3] At Howard Beach, passengers would ride a shuttle bus to the airport.[17][18] For many years, the shuttle buses transported passengers between the different airport terminals within JFK's Central Terminal Area, as well as between Howard Beach and the terminals.[19] The JFK Express service was unpopular with passengers because of its high cost. Additionally, the shuttle buses from Howard Beach would often get stuck in traffic.[20][21]

In 1987 the Port Authority proposed an inter-terminal rail connector at JFK as part of a $3 billion renovation program at JFK, LaGuardia, and Newark airports. It would connect a new five-story, $500 million transportation center with all of the airport's terminals.[22] The two-track system would be able to accommodate 2,000 riders an hour and would also travel to another new structure, a $450 million terminal proposed by Pan American World Airways.[23] If built, the rail connector and the transport hub would alleviate traffic at the airport. During the previous year, all three airports had experienced an unusually large increase in passenger counts and were now accommodating one-and-a-half to two times their design capacity.[24] This construction was proposed in conjunction with the JFK Expressway, which was already under construction.[23] Architect Henry N. Cobb of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners created a design for the terminal and the proposed people mover system.[25] However, the Port Authority withdrew its plans for the large transport hub in 1990 after objections from the airlines, which could not pay for the costly renovation.[25][26]

Plan for direct rail link

By the 1990s, there was also a need for a direct link between Midtown Manhattan and JFK Airport, which are 15 miles (24 km) away by road. During rush hour, the travel time from JFK to Manhattan could average up to 80 minutes by bus. Outside of rush hours, a taxi could make that journey in 45 minutes, while a bus could cover the same distance in an hour.[2] The Port Authority, foreseeing economic growth for the New York City area and increased air traffic at JFK, began planning for a direct rail link between Manhattan and JFK. In 1990, the United States Congress passed the Aviation Safety and Capacity Expansion Act (H.R. 5170). This allowed airport authorities to impose fees on passengers departing from their respective airports, then using these funds to improve the airports.[2] After the act was passed, the Port Authority added a Passenger Facility Charge (PFC) of $3 for every passenger departing from JFK.[2][26][27] This charge was implemented in 1991 and was projected to add an annual $120 million of funding for JFK Airport.[28]

In 1990, the MTA proposed a direct rail link to the two Queens airports (LaGuardia and JFK), which would be funded jointly by agencies in the federal, state, and city government.[21] The rail line was to begin in Midtown Manhattan, crossing the East River via the Queensboro Bridge's lower-level outer roadways, which had been formerly used by trolley cars.[29] It would stop at Queens Plaza, then travel northeast using the right-of-way of the Sunnyside Yards and Brooklyn-Queens Expressway to access LaGuardia Airport.[30] After stopping at LaGuardia, the line would continue southeast, parallel to the Grand Central Parkway and an intermediate stop near Shea Stadium in Willets Point, with a connection to the 7 and <7> trains at the Willets Point Boulevard subway station.[21][30] Continuing south along the parkway, the line would have another intermediate stop in Jamaica, connecting to the LIRR at Jamaica Station, and then proceed nonstop down the Van Wyck Expressway to JFK Airport.[21][30] However, the Port Authority found in April 1991 that the ridership demand might not justify the cost of the rail link between the two airports. As a result, the MTA reduced the priority of building the link.[31]

In September 1991, Governor Mario Cuomo put his support behind this rail plan, which would cost $1.6 billion if built.[26] Queens borough president Claire Shulman also endorsed the rail link.[20][29] The Regional Plan Association (RPA), a transport-advocacy group, opposed the link, and its leaders called the plan "misguided".[29] The East Side Coalition on Airport Access's executive director later said of the plan, "We are going to end up with another Second Avenue subway, another 63rd Street tunnel, another uncompleted project in this city."[29]

By 1992, the rail link proposal had gained traction with the Port Authority, which had started reviewing blueprints for the JFK rail link. At the time, it was thought that the link could be partially open by 1998.[28] In 1994, the Port Authority set aside $40 million for engineering and marketing of the new line, and created an environmental impact statement (EIS).[32] The EIS, conducted by the New York State Department of Transportation and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), found the plan to be feasible. However, the project attracted opposition from area residents and advocacy groups.[33] The PFC funds being collected by the Port Authority were supposed to fund the project, whose budget had grown to $2.6 billion.[32] The project was to start in 1996, but there were disputes over where to locate the Manhattan terminal. The intersection of Lexington Avenue and 59th Street was originally proposed for the terminal's site due to its high concentration of airport travelers. Manhattan community leaders, however, were concerned over the volume of traffic that would result from building the terminal there.[29][32] Many East Midtown residents opposed the Manhattan terminal outright because it would cause more limousine and taxi traffic in the neighborhood. It would remove two travel lanes from the Queensboro Bridge as well.[34] The Port Authority did not consider a connection to Grand Central Terminal or Penn Station, which both have a higher ridership base, because such a connection would be too expensive and complicated.[29] To pay for the project, the Port Authority would charge a one-way ticket price of between $9 and $12.[29]

By February 1995, plans for the link were in jeopardy, as the cost of the proposed link had increased from $2.6 billion to over $3 billion in the previous year alone. This caused the Port Authority to consider abridging the rail link plan, seeking federal and state funding, or partnering with private investors. Mario Cuomo's successor, George Pataki, expressed skepticism about the JFK rail link's viability during the previous year's gubernatorial campaign.[29] Instead of going to Manhattan directly, the rail link might have connected to Queens subway stations to reduce costs.[29]

Curtailment of plan

The direct rail link between LaGuardia/JFK and Manhattan was canceled outright in May 1995.[35][20][36] The plan had failed to gain traction politically, as it would have involved raising tolls and PATH fares to pay for the new link.[35] The 1990s economic recession also meant there was little chance of the entire plan being implemented due to its rising price.[35][37] The proposed JFK Airport connection was downsized to a 7.5-mile (12.1 km) monorail or people mover.[20] The original plan was to create a monorail, similar to the AirTrain Newark monorail that would open the following year.[38] In August 1995, the FAA approved the Port Authority's request to use the already collected PFC money to fund the new monorail plan instead.[37] By this time, the Port Authority hoped to begin construction in 1997 and open the $827 million line to Howard Beach by 2002.[36][37] It had already collected $114 million in PFC fees for the canceled JFK rail link project, and was planning to collect another $325 million from the charge.[36] By 1997, the agency had collected $441 million in PFC funds.[39]

The Port Authority voted to proceed with the scaled-down system in 1996.[40] A final environmental impact statement (FEIS) for the JFK people mover, conducted by the Port Authority and released in 1997, examined eight possible transport improvements that could be constructed in order to provide this direct connection.[41] Ultimately, a light rail with the qualities of a people mover, tentatively called the "JFK Light Rail System", was selected as the most feasible mode of transportation for the new system.[42] It would replace the shuttle buses that traveled between the terminals as well as to and from Howard Beach.[43] The FEIS determined that an automated system with frequent headways was the best design.[44] The light rail would run from the airport terminals to either Jamaica or Howard Beach.[45][46] It had been almost 30 years between the first JFK rail link proposal and the approval of the light rail system. According to The New York Times, twenty-one proposals for direct rail links to New York-area airports had been canceled during that period.[45]

While Governor Pataki supported this revised, $1.5 billion people mover plan, Mayor Rudy Giuliani voiced his opposition over the fact that it was not a direct rail link from Manhattan, and thus would not be profitable because of the need to transfer from Jamaica.[45][39][47] Giuliani also did not like that the city had to effectively pay $300 million toward the new light rail system. The Port Authority was originally planning to pay for only $1.2 billion of the project, with the other $300 million to be used to pay the rent at the airport instead.[45][39] In order to give his agreement, Giuliani wanted the Port Authority to study extending the Astoria elevated to LaGuardia Airport, as well as making the light-rail system compatible with the subway or LIRR to allow possible future interoperability.[48] In late 1997, Giuliani agreed to the plan on the condition that the state reimburse the city $300 million of the system's cost, with the city paying the $300 million for the line from 2002 through 2017.[45][49] As part of the agreement, the state would also conduct a study on a similar train link to LaGuardia Airport.[49]

In 1999, the RPA published an unofficial proposal for several new New York City Subway services, including one service that would travel directly to JFK Airport via the JFK Light Rail.[50] The new set of extensions proposed by the RPA, dubbed "MetroLink", consisted of 31 new subway stations, three stations converted from commuter rail use, and 12 mi (19 km) of new routes. One of the proposed subway services would have started at Grand Central–42nd Street; traveled south along the Second Avenue Subway and the Montague Street Tunnel to Brooklyn; used the LIRR Atlantic Branch to travel eastward from Atlantic Terminal to Jamaica; and then used the JFK Light Rail's trackage to travel south to JFK Airport.[51]

Construction

The Port Authority could only use the funds from the Passenger Facility Charge for the exclusive benefit of airport passengers. As a result, only the sections linking Jamaica and Howard Beach to JFK Airport were approved and built. The expectation was that airport travelers would be the sole passengers on the system.[44] The federal government approved the use of PFC funds for the new light rail system in February 1998, allowing construction to proceed. However, some $200 million of the funding could not be paid off using the PFC tax.[52]

Construction of the system began in May 1998.[53][54] Most of the system was built one span at a time, with cranes mounted on temporary structures erecting new spans as they progressed along the structures. However, some sections were built using a balanced cantilever design, where spans were first built on their own and then connected to each other using the span-by-span method.[55] The fact that the Jamaica branch had to be built in the middle of the Van Wyck Expressway, combined with the varying length and curves of the track spans, caused complications during construction. One lane was closed in each direction during off-peak hours, causing congestion on the Van Wyck.[54]

The AirTrain JFK route ran mostly along existing rights-of-way, but three commercial properties, including a gas station and a vacant building, were expropriated and demolished to make way for the AirTrain alignment.[56] Members of the New York City Planning Commission approved several buildings along the route being condemned in May 1999 but voiced concerns about the logistics of the project. These concerns included the projected high price of the tickets, ridership demand, and unwieldy transfers at Jamaica.[57]

Community leaders supported the project because of its connections to the Jamaica and Howard Beach station. However, almost all the civic groups along the Jamaica branch's route opposed it due to concerns about nuisance, noise, and traffic.[57] There were multiple protests against the AirTrain project; during one such protest in 2000, a crane caught fire in a suspected arson.[58] Homeowners in the vicinity believed the concrete supports would lower the price of their houses.[54] Residents were also concerned about the noise that an elevated structure would create. This was a major reason for the cancellation of the LaGuardia Airport connection.[20] According to a 2012 study, the majority of residents' complaints were due to "nuisance violations".[54] The Port Authority responded to residents' concerns by imposing strict rules regarding disruptive or loud construction activity. It also implemented a streamlined damage claim process which quickly compensated homeowners who suffered damage to their homes as a result of the construction.[59] Through 2002, there were 550 nuisance complaints over the AirTrain's construction, of which 98% had been resolved by April of that year.[60] On the other hand, at least one community board—Queens Community Board 12, which includes South Jamaica along the AirTrain's route—recorded few complaints about AirTrain construction.[61]

The Air Transportation Association of America (ATA), a lobbying group and trade organization representing several airlines, formed alliances with several community groups who opposed the AirTrain's construction.[62] In January 1999, the ATA filed a lawsuit in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit against the FAA over alleged misuse use of Passenger Facility Charge funds for the project. In March, Judge Laurence Silberman ruled the FAA did not misuse PFC funds in constructing the Van Wyck section of the AirTrain; however, he also found that after the AirTrain's public comment period had lapsed, the FAA had incorrectly continued to collect and make use of comments posted after the deadline. As a result, he vacated the project's approval.[63][64] The FAA then opened a second request for public comment; approval was granted again.[64][65] In 2000, the Southeast Queens Concerned Neighbors (SQCN) and the Committee for Better Transit (CBT), two advocacy groups consisting of local residents, also filed a federal lawsuit claiming that the FEIS had published misleading statements about the effects of the elevated structure on southern Queens neighborhoods.[66] The ATA, along with the SQCN and the CBT, appealed the funding decision in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.[67] The ATA subsequently withdrew from the lawsuit following negotiations with the Port Authority. However, the CBT proceeded with an appeal, which it lost.[67] In denying the lawsuit, Judge Robert Katzmann wrote that "...the FAA's interpretation of the PFC statute is reasonable and consistent with the statute's purpose".[68]

By the time the AirTrain case appeal was decided in October 2000, two-thirds of the system's viaduct structures had been constructed. [67] The system was ready for its first test trains by December 2000.[66] The state spent $75 million to renovate the Howard Beach station, which brought it into ADA compliance and facilitated passengers' transfers to and from the AirTrain.[69] The new Howard Beach station was completed in May 2001.[70] The Port Authority also contributed $100 million toward the Jamaica LIRR station renovations, with the State of New York paying for the rest of the $387 million project. The purpose of this renovation was, in part, to facilitate AirTrain connections.[69] Renovation of the Jamaica station started in May 2001 after the completion of the Howard Beach station.[70] By this time, the system's guideway rails were complete, and the guideways were being constructed. The first two AirTrain cars were delivered in March 2001 and underwent testing at the AirTrain maintenance facility near Lefferts Boulevard.[61] The guideways were completed in August 2001.[71] However, a proposed parking structure near the Jamaica terminal—part of a long-term plan to redevelop downtown Jamaica—was largely unfunded by 2002, the year the AirTrain was originally supposed to open.[72]

Opening and effects

Service was to begin in October 2002.[53][60] The Howard Beach branch was supposed to open first, with the Jamaica branch opening later, in 2003.[73] As part of the original plan, the Jamaica station would be completed by 2005.[60] However, the start of passenger service was delayed because of several incidents during the system's testing process.[74] In July 2002, an AirTrain derailed, injuring three workers on board the train.[74] On September 27, 2002, a train operator died in another derailment during a test run,[75] which delayed the system's opening.[76] The National Transportation Safety Board investigated the crash[74] and found that the train had sped excessively on a curve at the time of the crash.[77][78] After the death, Southeast Queens residents feared the project could become a "boondoggle".[59] By this time, the system had cost $1.9 billion to build.[27][79]

Following the fatal crash, the entire system was set to open in June 2003.[80] Its opening date was later postponed to December 17, 2003.[79] AirTrain JFK and the rest of the airport, like other Port Authority properties, did not receive subsidies from the state or city for its operating costs. This was one of the reasons cited for AirTrain JFK's relatively high fare.[81]

After AirTrain JFK began operations, Jamaica saw a boom in commerce, and a 15-screen movie theater opened in the area less than a year after the system opened.[82] Several projects were also developed in anticipation of the AirTrain's opening. By June 2003, a 50,000-square-foot (4,600 m2), 16-story building was being planned for Sutphin Boulevard across from the new station. Other nearby projects built in the preceding five years included the Jamaica Center Mall, Joseph P. Addabbo Federal Building, the Civil Court, and the Food and Drug Administration Laboratory and Offices.[83] In 2004, the city proposed rezoning a 40-block swath of Jamaica, centered around the AirTrain station, as a commercial area. This mixed-use "airport village" was to consist of 5,000,000 square feet (460,000 m2) of space. By the time the rezoning was proposed, a 400,000-square-foot (37,000 m2), 13-floor structure in the area was already being planned by a developer.[82] The idea was for Jamaica to be re-envisioned as a "regional center", according to the RPA, since during the average weekday, 100,000 LIRR riders and 53,000 subway riders used stations in the core of Jamaica. A proposal calling for a 250-room hotel above the AirTrain terminal was canceled after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.[82] The Port Authority estimated that the AirTrain JFK would carry 12.4 million passengers a year.[82] The Jamaica station's renovation was completed in 2006, three years after the system opened.[84]

Even before the AirTrain was completed, there were plans to eventually extend it to Manhattan.[85] Between September 2003 and April 2004, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, the MTA, the Port Authority, and the New York City Economic Development Corporation conducted a feasibility study of the Lower Manhattan–Jamaica/JFK Transportation Project. It would use the LIRR's Atlantic Branch to Downtown Brooklyn and a tunnel to Lower Manhattan. This would provide faster service to JFK without having to change trains, and LIRR service to Lower Manhattan via a transfer at Jamaica, in a manner similar to the plan proposed by the RPA in 1999. Under this proposal, baggage could be checked in Manhattan and transferred directly to planes at the airport.[86] The study examined several alternatives, including using the existing Cranberry Street Tunnel or Montague Street Tunnel under the East River, or building an entirely new cross-river tunnel.[87] The project was halted in 2008 before an environmental impact statement could be created.[88] By the time the project was canceled, its projected total cost had risen from $6 billion to between $8.6 and $9.9 billion.[89]

Following President Donald Trump's signing of Executive Order 13769 in January 2017, which restricted immigration from some countries, protests were held at JFK Airport. Taxi drivers refused to take passengers to or from the airport, so the Port Authority closed the AirTrain as a precaution against overcrowding.[90] Governor Andrew Cuomo later reversed this shutdown.[91][92]

Renovation of JFK Airport

On January 4, 2017, the office of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a plan to renovate the entire airport at a cost of $7–10 billion.[93][94] As part of the project, the AirTrain JFK would either see lengthened trainsets or a direct track connection to the rest of New York City's transportation system. There would also be a rebuilding of the Jamaica station so that there is a direct connection to the Long Island Rail Road and New York City Subway.[95] Shortly after Cuomo's announcement, the Regional Plan Association published a study of a possible direct rail link from Manhattan.[96][97] In July 2017, Cuomo's office began accepting proposals for master plans to renovate the airport.[98][99]

In October 2018, Cuomo released details of his $13 billion plan to rebuild passenger facilities and approaches to JFK Airport. The redesign proposal includes adding cars to AirTrain consists to increase capacity, in addition to widening connector ramps between the Van Wyck Expressway and Grand Central Parkway in Kew Gardens, and adding another lane in each direction to the Van Wyck.[100][101] If the proposal is approved, construction on the new airport facilities is expected to begin in 2020.[102][103]

System

Routes

AirTrain JFK connects John F. Kennedy International Airport's airport terminals and parking areas with LIRR and subway lines at Jamaica and Howard Beach stations, and is located entirely within the New York City borough of Queens. The system consists of three routes: one route each connecting the terminals with the Howard Beach and Jamaica stations, and one route looping continuously around the central terminal area.[104][105][106]

The Howard Beach route begins and ends at Howard Beach–JFK Airport, with a direct transfer to the New York City Subway's IND Rockaway Line (A train).[107] It also stops at Lefferts Boulevard for transfers to shuttle bus service to long term parking lots A and B and to the airport employee parking lot, as well as to the B15 bus to Brooklyn.[104][105][106] The line segment from Howard Beach to Federal Circle, which crosses the employee and long-term parking lots, is about 1.8 miles (2.9 km) long.[108]

The Jamaica route begins and ends at Jamaica station, adjacent to the Long Island Rail Road with a connection available to Sutphin Boulevard–Archer Avenue–JFK Airport on the New York City Subway's Archer Avenue Line (E, J, and Z trains).[109][107] The AirTrain and LIRR stations connect to the subway station by an elevator bank. Transfers to Nassau Inter-County Express, MTA Regional Bus, and private bus routes are available at the station.[104][105][106] Heading west from Jamaica, the line travels above the north side of 94th Avenue before curving southward onto the Van Wyck Expressway. The segment of line from Jamaica to Federal Circle is about 3.1 miles (5.0 km) long.[108]

The Howard Beach and Jamaica routes merge at Federal Circle for car rental companies and shuttle buses to hotels and the airport's cargo areas. South of Federal Circle, the routes share track for 1.5 miles (2.4 km), entering a tunnel before the tracks separate in two directions for the 2-mile (3.2 km) terminal loop.[110] Both routes continue in a counterclockwise direction and stop at each of the six terminals, serving Terminals 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8.[106]

The All Terminals loop, an airport terminal circulator, serves the six terminal stations. It operates in the opposite direction as the Howard Beach and Jamaica branches, making a continuous clockwise loop around the terminals. Connections to the Q3, Q10 and B15 local buses are available at Terminal 5.[104][105][106]

As planned, counterclockwise trains, to and from Jamaica and Howard Beach, would have run every two minutes during peak hours, for a frequency of 30 trains per hour. Each branch would have been served by a train every four minutes, with a frequency of 15 trains per hour.[111] The final environmental impact statement planned for even higher frequencies of 40 trains per hour, or a train every 90 seconds in the central terminal area.[112] However, as of 2014, actual frequencies were much lower, with each branch being served by one train every seven to 12 minutes during peak hours, or 5 to 8.5 trains per hour. During midday, trains arrived every 10 to 15 minutes on each branch. Each branch was served by a train every 15 to 20 minutes during late nights, and every 16 minutes during weekends.[113] Trains made the journey between the terminals and either Jamaica or Howard Beach in about eight minutes.[114]

Stations

All AirTrain JFK stations are fully compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) by means of elevators in each station.[115] Each platform is 240 feet (73 m) long and can fit up to four cars.[116] The stations contain platform screen doors for passenger safety and climate control,[107] and to ensure the safe operation of the unmanned trains.[44] Stations also contain safety systems like CCTV cameras, alarms, and emergency contact points. Each station is also manually staffed by attendants.[44]

All of the stations have an island platform layout except for Federal Circle, which has a split platform layout.[106] The Jamaica and Howard Beach stations are designed as "gateway stations" where, upon entering, passengers transferring from the subway and LIRR are given the impression that they have entered the airport.[117]

| Station[115] | Lines[115] | Connections[113] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Howard Beach 40°39′40″N 73°49′46″W / 40.661043°N 73.829455°W |

|

|

|

| Lefferts Boulevard 40°39′41″N 73°49′22″W / 40.661374°N 73.822660°W |

|

|

|

| Federal Circle 40°39′36″N 73°48′13″W / 40.659898°N 73.803602°W |

|

|

|

| Jamaica 40°41′57″N 73°48′29″W / 40.69904°N 73.80807°W |

|

|

|

| Terminal 1 40°38′37″N 73°47′22″W / 40.643577°N 73.789348°W |

|

|

|

| Terminal 2 40°38′31″N 73°47′15″W / 40.642048°N 73.787378°W |

|

|

Originally named Terminals 2 and 3.[118] |

| Terminal 4 40°38′38″N 73°46′56″W / 40.643974°N 73.782273°W |

|

|

|

| Terminal 5 40°38′49″N 73°46′48″W / 40.646878°N 73.780067°W |

|

|

Originally named Terminals 5 and 6.[118] |

| Terminal 7 40°38′54″N 73°47′00″W / 40.648266°N 73.783422°W |

|

|

|

| Terminal 8 40°38′48″N 73°47′19″W / 40.646781°N 73.788709°W |

|

|

Originally named Terminals 8 and 9.[118] |

Except for Terminal 2 & 4, all stations in the airport are freestanding structures, connected to their respective terminal buildings by an aerial walkway. Terminal 2 requires you to take an elevator to street level and cross via covered sidewalks. Terminal 4 opened in 2013 with the station inside the terminal building itself.[119]

Specifications

The total route length of the system is 8.1 miles (13.0 km), with the terminal-area loop being 1.8 miles (2.9 km).[43] The system consists of 6.3 miles (10.1 km) of single-track and 3.2 miles (5.1 km) of double-track guideways.[120] The tracks are set at a gauge of 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm).[116] This enables possible future conversion to LIRR or subway use, or a possible connection to LIRR or subway tracks for a one-trip ride into Manhattan.[53][121][122][114] However, AirTrain's current rolling stock, or train cars, are not able to use either LIRR or subway tracks due to their inadequate structural strength and different method of propulsion. In particular, the linear induction motor system that propels the AirTrain vehicles cannot be used on LIRR and subway tracks because the train cars on these lines are manually propelled by traction motors.[122] If a one-seat ride is ever implemented, a hybrid-use vehicle would be needed to operate on both subway/LIRR and AirTrain tracks.[122][114]

The system is mostly elevated. The elevated sections were built with precast single and dual guideways, while the underground sections used cut-and-cover, and the at-grade sections used concrete ties and ballast trackbeds. The single guideways carry one track each and are 19 feet 3 inches (5.87 m) wide, while the double guideways carry two tracks each and are 31 feet 0 inches (9.45 m) wide. Columns support the precast concrete elevated sections at intervals of no more than 40 feet (12 m).[116] The system has seven electrical substations to ensure that in the case of power outages at one substation, trains can still operate.[107] The elevated structures were designed to resist minor seismic events, utilizing seismic isolation bearings and soundproof barriers to protect from small earthquakes as well as prevent noise pollution.[55] The AirTrain uses steel tracks[112] that are continuously welded across all joints except at the terminals; the elevated guideways are also continuously joined.[123] Trains use double crossovers at the Jamaica and Howard Beach terminals in order to switch to the track going in the opposite direction. There are also crossover switches north and south of Federal Circle, counterclockwise from Terminal 8, and clockwise from Terminal 1.[124] In case of an emergency, a control tower can automatically guide the train to its next stop where passengers can disembark; there are no emergency exits between stations.[60]

Fares

AirTrain JFK is free to use within the terminal area, as well as to and from hotel and car-rental shuttle buses at Federal Circle. Passengers entering or leaving the system at the Jamaica or Howard Beach stations pay a $5 fare using a MetroCard. A $1 fee is charged for all new MetroCard purchases.[125] Transferring to the Q3, Q10, or B15 buses from Terminal 5, or to the subway at Howard Beach and Jamaica, requires an extra $2.75 fare, since the MTA does not offer free transfers from the AirTrain. Passengers would pay $7.75 if they transferred between the AirTrain and the subway at either Howard Beach or Jamaica. Entering the LIRR at Jamaica costs $14.25 during peak hours and $9 during off-peak periods with the LIRR CityTicket.[126]

AirTrain JFK MetroCards can be purchased from vending machines at Jamaica and Howard Beach with cash, credit card, or ATM card. One reduced fee option is the "30-Day AirTrain JFK MetroCard", which is $40 for unlimited rides and valid only on AirTrain JFK.[127] The AirTrain JFK 10-Trip MetroCard costs $25 and is good for ten trips on the AirTrain only until midnight six months after first use.[127] This card is only accepted on AirTrain JFK, and one trip is deducted for each use.[125] When the AirTrain JFK system first opened, it only accepted pay-per-ride MetroCards for fare payment.[79] This option is still available; however, standard unlimited MetroCards are not accepted on AirTrain JFK.[127]

As originally planned, the fee to enter or exit at Howard Beach and Jamaica would have been $5, with airport and airline employees receiving a discounted fare of $2.[112] The original proposal also called for fare-free travel between airport terminals,[112] which was ultimately implemented.[125]

Ridership

When AirTrain JFK was being planned, it was expected that 11,000 passengers per day would pay to ride the system between the airport and either Howard Beach or Jamaica. 23,000 more daily passengers would use the AirTrain to travel between terminals. This would amount to about 4 million paying passengers and 8.4 million in-airport passengers per year.[56] The system would cause a reduction of approximately 75,000 vehicle miles driven per day, as well as accommodate over 3,000 daily riders from Manhattan, according to the FEIS.[128] During the first month of service, an average of 15,000 daily passengers rode either the paid or unpaid sections of the system, less than the 34,000 expected daily riders.[129] This made it the second-busiest airport transportation system in the United States, even though it had been open for only a month.[107] Since then, ridership has continued to rise.[130][131] AirTrain JFK transported 1 million riders within its first six months.[132]

In 2014, the most recent year for which statistics are available, AirTrain JFK carried 6,487,118 paying passengers, with another 10 million using the service for free on-airport travel.[130] This represents a 247% increase over 2004, the first full year of operation, when 2,623,791 riders paid. Of the 53.2 million passengers who used JFK in 2014, twelve percent paid a fare to travel on AirTrain JFK.[131] The ridership of AirTrain JFK has risen each year from 2004 to 2014.[130][131] The AirTrain's $5 fare is cheaper than the $45 taxi ride between Manhattan and JFK, which may be a factor in the AirTrain's increasing ridership.[133]

Rolling stock

AirTrain JFK uses Bombardier Transportation's Innovia Metro rolling stock and technology, similar to what is also used on the SkyTrain in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, and on the Kelana Jaya Line in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.[107] The computerized trains are fully automated and use a communications-based train control system with moving block signals to dynamically determine the locations of the trains. The cars do not have conductors or motormen, making AirTrain JFK a wholly driverless system.[107] The CBTC system uses Thales Group's SelTrac technology.[134] Trains are operated from and maintained at a 10-acre (4 ha) train yard between Lefferts Boulevard and Federal Circle, atop a former employee parking lot.[135] The system uses pre-recorded announcements by New York City traffic reporter Bernie Wagenblast, who had previously worked with the Port Authority for two decades.[136]

The 32 individual (non-articulated) Mark II vehicles operating on the line draw power from a 750V DC top-running third rail. A linear induction motor pushes magnetically against an aluminum strip in the center of the track. The vehicles also have steerable trucks that can navigate sharp curves and steep grades, as well as align precisely with the platform doors at the stations.[137][107] The cars can run at up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h).[124] Each car is 57 feet 9 inches (17.60 m) long by 10 feet 2 inches (3.10 m) wide,[116] with dimensions similar to rolling stock used on the B Division of the New York City Subway. Trains can run in either direction, and can consist of between one and four cars.[107] Each car has 26 seats and can carry 97 passengers with luggage or 205 without luggage.[116] A car's operating capacity is only 75 to 78 passengers because most passengers are expected to carry luggage.[137] There are two doors per side per car; each pair of doors is about 10 feet 5 inches (3.18 m) wide.[116] The trains can operate on trackage with a minimum railway curve radius of 230 feet (70 m).[124][116]

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 "Full text of "Metropolitan transportation, a program for action. Report to Nelson A. Rockefeller, Governor of New York."". November 7, 1967. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES2.

- 1 2 UCL Bartlett 2011, p. 32.

- 1 2 "JFK rail link "not feasible," Ronan says" (PDF). The Daily News. Tarrytown, NY. Associated Press. April 21, 1976. Retrieved September 11, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "33d St. Terminal Picked for Kennedy Rail Link; Underground Site Will Have at Least Two Tracks". The New York Times. June 2, 1969. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ↑ "Urge Rockaway Tie-in With JFK Subway Spur" (PDF). The Wave. Rockaway Beach, NY. February 8, 1973. p. 1. Retrieved September 5, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "NYC Okays Speed Trains Between JFK, Penn Depot" (PDF). Herald Statesman. Yonkers, NY. November 14, 1969. p. 4. Retrieved September 13, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Short, Dorsey (September 30, 1974). "JFK Speed Line Will Have Woodhaven Stop" (PDF). Ridgewood Times. p. 1. Retrieved September 5, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Airport Rail Line Needs Subway in Park" (PDF). The Wave. Rockaway Beach, NY. February 15, 1973. p. 1. Retrieved September 5, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Short, Dorsey (March 22, 1973). "Santucci Says Rail Link May Destroy Forest Park" (PDF). Ridgewood Times. p. 8. Retrieved September 5, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Better Transit Eyes Link Of JFK-Subway—Fetscher" (PDF). The Wave. Rockaway Beach, NY. October 7, 1974. p. 3. Retrieved September 5, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Raskin, Joseph B. (November 1, 2013), The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City's Unbuilt Subway System, Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-8232-5369-2

- ↑ "Better Transit Eyes Link Of JFK-Subway—Fetscher" (PDF). The Wave. Rockaway Beach, NY. March 8, 1978. p. 1. Retrieved September 5, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Plan Transitway Hearing" (PDF). Ridgewood Times. July 8, 1982. Retrieved September 13, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Port Authority Drops Transitway Plan". Ridgewood Times. January 27, 1983. pp. 1, 10 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Grynbaum, Michael M. (November 25, 2009). "If You Took the Train to the Plane, Sing the Jingle". City Room. The New York Times. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- 1 2 "New "JFK Express" Service Begun in Howard Beach" (PDF). New York Leader Observer. September 28, 1978. Retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Herszenhorn, David M. (August 20, 1995). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: HOWARD BEACH; Rethinking Plans For Those Trains To the Planes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Sims, Calvin (March 18, 1990). "M.T.A. Proposes Rail Line to Link Major Airports". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Schmitt 1987, pp. 1, 2.

- 1 2 Schmitt 1987, p. 2.

- ↑ Schmitt 1987, p. 1.

- 1 2 Goldberger, Paul (June 17, 1990). "Architecture View: Blueprint an Airport that Might Have Been". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Steinberg, Jacques (December 28, 1991). "Port Authority Plans Changes At Kennedy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 Topousis, Tom (November 26, 2000). "JFK Revamp Takes Off Facelift Will See Airport Flying into the Future". New York Post. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 Dao, James (December 21, 1992). "Dream Train to Airports Takes Step Nearer Reality". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Levy, Clifford J. (February 1, 1995). "Port Authority May Scale Back Airport Rail Line". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Firestone 1994, p. 1.

- ↑ Strom, Stephanie (April 27, 1991). "Proposal to Link Airports by Rail Is Dealt Setback". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Lambert, Bruce (June 19, 1994). "Neighborhood Report: East Side; Site for Airport Link Is Disputed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Firestone 1994, pp. 1, 2.

- ↑ Firestone 1994, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Purnick, Joyce (June 5, 1995). "Metro Matters: The Train to the Plane Turns to Pie in the Sky". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Donohue, Pete (August 2, 1995). "JFK Light Rail Moves Forward". Daily News. New York. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Levy, Clifford J. (August 2, 1995). "A Monorail For Kennedy Is Granted Key Approval". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Levy, Clifford J. (July 23, 1995). "A Worry in Queens: Newark Airport's Monorail Might Work". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Macfarquhar, Neil (June 14, 1997). "Disagreement Over Rent Stalls Airport Rail Project". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Sullivan, John (May 10, 1996). "Port Authority Approves a Rail Link to Kennedy Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES3.

- ↑ EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES4.

- 1 2 Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Newman, Andy (October 2, 1997). "Officials Agree On Modest Plan For a Rail Link To One Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ EIS Volume 1 1997, pp. ES11, 1.4.

- ↑ Levy, Clifford J. (May 3, 1996). "Pataki Supports Two-Train Link to Kennedy Airport That GiulianiOpposes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Macfarquhar, Neil (March 13, 1997). "Agency Says J.F.K. Rail Plan Is Ready, but Mayor Balks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 Feiden, Douglas (October 1, 1997). "JFK-RAIL PLAN TO GET RUDY'S OK". NY Daily News. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Regional Plan Association 1999, pp. 2, 12.

- ↑ Regional Plan Association 1999, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Wald, Matthew L. (February 10, 1998). "Plan Approved for a Kennedy Rail Link". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Chan, Sewell (January 12, 2005). "Train to JFK Scores With Fliers, but Not With Airport Workers". The New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 UCL Bartlett 2011, p. 22.

- 1 2 Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 10.

- 1 2 EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES10.

- 1 2 Herszenhorn, David M. (May 4, 1999). "Still Opposed, Planners Let Airport Link Go Ahead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Schwartzman, Bryan (June 8, 2000). "JFK Airtrain Project Fire Suspicious: Police". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 3 4 Dentch, Courtney (April 18, 2002). "AirTrain System Shoots for October Start Date". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 Scheinbart, Betsy (March 29, 2001). "No Hitches in AirTrain Construction". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Barnes, Julian E. (November 15, 1998). "Neighborhood Report: New York Up Close; Designs for a Kennedy Rail Terminal Provoke Foes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ↑ Text of Air Transport Association of America, Petitioner, v. Federal Aviation Administration, United States Department Oftransportation, and United States of America, Respondents. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Intervenor, 169 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 1999) is available from: Justia

- 1 2 "FAA Statement on JFK Airport Light Rail System" (Press release). Federal Aviation Administration. August 16, 1999. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ↑ Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 5.

- 1 2 "POSTINGS: Work Continues on Rail Route to JFK; First Test Nears for AirTrain". The New York Times. September 17, 2000. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Bertrand, Donald (October 18, 2000). "Court Spurns AirTrain Lawsuit Upholds Use Of Airport Taxes". Daily News. New York. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Text of Southeast Queens Concerned Neighbors, Inc. and the Committee for Better Transit, Inc. Petitioners, v. Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, and United States of America Respondents, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Intervenors. 229 F.3d 387 (2nd Cir. 2000) is available from: CourtListener FindLaw

- 1 2 Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 4.

- 1 2 Scheinbart, Betsy (May 10, 2001). "AirTrain construction starts on Jamaica station". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ Scheinbart, Betsy (August 23, 2001). "AirTrain's guideway above Van Wyck is complete". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Scheinbart, Betsy (January 3, 2002). "No money for parking at AirTrain". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Newman, Philip (July 18, 2002). "AirTrain on track to begin runs to Jamaica next year". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Boniello, Katherine; Dentch, Courtney (October 3, 2002). "Feds investigate fatal AirTrain accident". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Tarek, Shams (October 4, 2002). "Following AirTrain Accident, A Community Mourns". Southeast Queens Press. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ↑ Shen, Maxine (September 28, 2002). "Airport Train Horror:Driver Killed in Test Run". New York Post. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy (October 18, 2002). "Inquiry Shows Speed of Test Run Caused Derailment of AirTrain". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ↑ Dentch, Courtney (October 10, 2002). "AirTrain Was Near Top Speed at Time of Crash: Feds". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Stellin, Susan (December 14, 2003). "Travel Advisory: A Train to the Plane, At Long Last". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ↑ Dentch, Courtney (February 27, 2003). "AirTrain May Start Service by June Despite Sept. Crash". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Holusha, John (February 29, 2004). "Commercial Property; Jamaica Seeks to Build on AirTrain". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (July 6, 2003). "Change at Jamaica". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ↑ Ain, Stewart (September 9, 2006). "Jamaica Station, $300 Million Later". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Dentch, Courtney (February 12, 2004). "Agencies Seek Extension of AirTrain Service". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ "Feasibility Study". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Lower Manhattan-Jamaica/JFK Transportation Project, Summary Report, Prepared for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and PANYNJ". Scribd. Parsons/SYSTRA Engineering, Inc. December 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ↑ Brown, Eliot (March 24, 2009). "The Tunnel From Nowhere". New York Observer. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Eli (January 29, 2017). "The Scene at JFK as Taxi Drivers Strike Following Trump's Immigration Ban". USA Today. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ↑ Hawkins, Andrew J. (January 28, 2017). "JFK airport roiled by protests against Trump's immigration ban". The Verge. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Eli (January 28, 2017). "Protest Grows 'Out of Nowhere' at Kennedy Airport After Iraqis Are Detained". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ↑ Barone, Vincent (January 4, 2017). "Cuomo unveils plan to breathe new life into JFK airport". am New York. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ↑ Kirby, Jen (January 5, 2017). "New York City's Second-Worst Airport Might Also Get an Upgrade". Daily Intelligencer. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ↑ "A Vision Plan for John F. Kennedy International Airport" (PDF). Airport Advisory Panel; Government of New York. January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017 – via Governor of New York.

- ↑ "Creating a One-Seat Ride to JFK" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. January 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ↑ Plitt, Amy (January 6, 2017). "One-Seat Rides to JFK Airport Are a Reality in This Public Transit Proposal". Curbed NY. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ↑ "New York launches next stage in JFK Airport overhaul". Deutsche Welle. Reuters and Bloomberg. July 19, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Governor of New York (July 18, 2017). "Governor Cuomo Announces RFP for Planning and Engineering Firm to Implement JFK Airport Vision Plan". Government of New York. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ "Cuomo's $13 Billion Solution to the Mess That Is J.F.K. Airport". The New York Times. October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Cuomo: JFK Airport renovation includes central hub, 2 new terminals". Newsday. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Governor Cuomo Announces $13 Billion Plan to Transform JFK Into a World-Class 21st Century Airport". governor.ny.gov. Government of New York. October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ↑ Rivoli, Dan. "Kennedy Airport to get $13 billion renovation and two new terminals". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "To & From JFK". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "JFK Airport AirTrain". Jfk-airport.net. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "AirTrain JFK opens for service". Railway Gazette International. March 1, 2004. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- 1 2 EIS Volume 1 1997, p. 1.12.

- ↑ Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ EIS Volume 1 1997, p. 1.13.

- ↑ Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 EIS Volume 1 1997, p. 1.5.

- 1 2 Port Authority 2014, pp. 1, 2.

- 1 2 3 Arema 1999, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Port Authority 2014, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bombardier Transportation 2004, p. 2.

- ↑ Arema 1999, pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 3 Bombardier Transportation 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ "Delta Opens New JFK Terminal 4 Hub". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ↑ Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 1.

- ↑ Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 3 Englot & Bakas 2002, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 "Cost and Tickets – AirTrain – Ground Transportation – John F. Kennedy International Airport". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ↑ "Airtrain JFK: Make the Connection". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "MTA/New York City Transit: Fares and MetroCard". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ EIS Volume 1 1997, pp. ES10–ES11.

- ↑ Dentch, Courtney (February 22, 2004). "AirTrain Ridership On Track to Meet Year-End Goal: PA". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Office of Governor Andrew Cuomo (February 10, 2015). "Governor Cuomo Announces AirTrain JFK Reaches Record High Ridership of 6.4 Million in 2014" (Press release). Government of New York. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Governor Cuomo Announces AirTrain JFK Reaches Record High Ridership in 2014". LongIsland.com. February 12, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ↑ Simon, Mallory (June 17, 2004). "AirTrain Awaits Millionth Rider Six Months Later". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ↑ Levere, Jane L. (August 10, 2009). "Trains and Vans May Beat Taxis to the Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ↑ "SelTrac™ CBTC Signalling Projects" (PDF). Thales Group. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 1, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ↑ EIS Volume 1 1997, pp. ES9, 1.18.

- ↑ "Bernie Wagenblast: The Voice of Public Transportation in the Region". PANYNJ PORTfolio. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. January 12, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- 1 2 Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 4.

Bibliography

- "The Airtrain Airport Access System John F. Kennedy International Airport" (PDF). American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association. 1999. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- "Advanced Rapid Transit System AirTrain JFK International Airport, New York, USA" (PDF). Bombardier Transportation. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "AirTrain JFK: The Fast, Affordable Connection" (PDF) (September 2014 ed.). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. September 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Englot, Joseph M.; Bakas, Paul T. (September 2002). "Performance/Design Criteria for the Airtrain JFK Guideway" (PDF). AREMA 2002 Annual Conference & Exposition. Washington, DC.

- Firestone, David (July 31, 1994). "The Push Is On for Link to Airports: Port Authority Confident of Rail Plan Despite Opposition". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Gosling, Geoffrey D.; Freeman, Dennis (May 2012). "Case Study Report: John F. Kennedy International Airport AirTrain" (PDF). Mineta Transportation Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- JFK International Airport Light Rail System: Environmental Impact Statement. Vol. 1. Federal Aviation Administration; New York State Department of Transportation. 1997. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- JFK International Airport Light Rail System: Environmental Impact Statement. Vol. 2. Federal Aviation Administration; New York State Department of Transportation. 1997. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- JFK International Airport Light Rail System: Environmental Impact Statement. Vol. 3. Federal Aviation Administration; New York State Department of Transportation. 1997. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "MetroLink" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. January 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Project Profile; USA; New York Airtrain" (PDF). University College London Bartlett School of Planning. September 6, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- Schmitt, Eric (February 2, 1987). "New York Airports: $3 Billion Program". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

External links

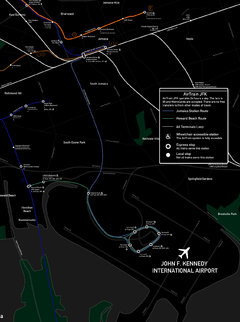

Route map:

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

- Official website