Chicago "L"

|

A Pink Line train approaches Randolph/Wabash. | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locale | Chicago, Illinois, United States | ||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 8[1] | ||

| Line number |

Red Line Orange Line Yellow Line Green Line Blue Line Purple Line Brown Line Pink Line | ||

| Number of stations | 145[1] | ||

| Daily ridership | 767,730 (average weekday, 2015)[2] | ||

| Annual ridership | 238.36 million (2016)[3] | ||

| Chief executive | Dorval R. Carter, Jr. | ||

| Headquarters |

567 West Lake St. Chicago, Illinois | ||

| Website | Chicago Transit Authority | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | June 6, 1892[1] | ||

| Operator(s) | Chicago Transit Authority | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 102.8 mi (165.4 km)[1][note 1] | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||

| Minimum radius of curvature | 90 feet (27,432 mm) | ||

| Electrification | Third rail, 600 V DC | ||

| Top speed | 55 mph (89 km/h) | ||

| |||

The Chicago "L" (short for "elevated")[4] is the rapid transit system serving the city of Chicago and some of its surrounding suburbs in the U.S. state of Illinois. It is operated by the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA). It is the fourth-largest rapid transit system in the United States in terms of total route length, at 102.8 miles (165.4 km) long,[1][note 1] and the second-busiest rail mass transit system in the United States, after the New York City Subway.[5]

Chicago's "L" provides 24-hour service on some portions of its network, being one of only five rapid transit systems in the United States to do so.[note 2] The oldest sections of the Chicago "L" started operations in 1892, making it the second-oldest rapid transit system in the Americas, after New York City's elevated lines.

The "L" has been credited with fostering the growth of Chicago's dense city core that is one of the city's distinguishing features.[6] The "L" consists of eight rapid transit lines laid out in a spoke–hub distribution paradigm focusing transit towards the Loop. Although the "L" gained its name because large parts of the system are elevated,[7][8] portions of the network are also in subway tunnels, at grade level, or open cut.[1]

In 2014, the "L" had an average of 752,734 passenger boardings each weekday, 486,267 each Saturday, and 359,777 each Sunday.[9] In a 2005 poll, Chicago Tribune readers voted it one of the "seven wonders of Chicago",[10] behind the lakefront and Wrigley Field, but ahead of Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower), the Water Tower, the University of Chicago, and the Museum of Science and Industry.

History

Pre-CTA era

.png)

The first "L", the Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad, began revenue service on June 6, 1892, when a steam locomotive pulling four wooden coaches, carrying more than a couple of dozen people, departed the 39th Street station and arrived at the Congress Street Terminal 14 minutes later,[11] over tracks that are still in use by the Green Line. Over the next year, service was extended to 63rd Street and Stony Island Avenue, then the Transportation Building of the World's Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park.[12]

In 1893, trains began running on the Lake Street Elevated Railroad and in 1895 on the Metropolitan West Side Elevated, which had lines to Douglas Park, Garfield Park (since replaced), Humboldt Park (since demolished), and Logan Square. The Metropolitan was the United States' first non-exhibition rapid transit system powered by electric traction motors,[12] a technology whose practicality had been demonstrated in 1890 on the "intramural railway" at the World Fair that had been held in Chicago.[13] Two years later the South Side "L" introduced multiple-unit control, in which the operator can control all the motorized cars in a train, not just the lead unit. Electrification and MU control remain standard features of most of the world's rapid transit systems.

A drawback of early "L" service was that none of the lines entered the central business district. Instead trains dropped passengers at stub terminals on the periphery due to a state law at the time requiring approval by neighboring property owners for tracks built over public streets, something not easily obtained downtown. This obstacle was overcome by the legendary traction magnate Charles Tyson Yerkes, who went on to play a pivotal role in the development of the London Underground, and who was immortalized by Theodore Dreiser as the ruthless schemer Frank Cowperwood in The Titan (1914) and other novels. Yerkes, who controlled much of the city's streetcar system, obtained the necessary signatures through cash and guile—at one point he secured a franchise to build a mile-long "L" over Van Buren Street from Wabash Avenue to Halsted Street, extracting the requisite majority from the pliable owners on the western half of the route, then building tracks chiefly over the eastern half, where property owners had opposed him. The Union Loop opened in 1897 and greatly increased the rapid transit system's convenience. Operation on the Yerkes-owned Northwestern Elevated, which built the North Side "L" lines, began three years later, essentially completing the elevated infrastructure in the urban core although extensions and branches continued to be constructed in outlying areas through the 1920s.

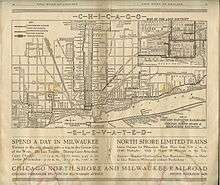

After 1911, the "L" lines came under the control of Samuel Insull, president of the Chicago Edison electric utility (now Commonwealth Edison), whose interest stemmed initially from the fact that the trains were the city's largest consumer of electricity. Insull instituted many improvements, including free transfers and through routing, although he did not formally combine the original firms into the Chicago Rapid Transit Company until 1924. He also bought three other Chicago electrified railroads, the Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad, Chicago Aurora and Elgin Railroad, and South Shore interurban lines, and ran the trains of the first two into downtown Chicago via the "L" tracks. This period of relative prosperity ended when Insull's empire collapsed in 1932, but later in the decade the city with the help of the federal government accumulated sufficient funds to begin construction of two subway lines to supplement and, some hoped, permit eventual replacement of the Loop elevated. The construction of the Subway created the necessity to tunnel under the Chicago River.

The State Street Subway opened on October 17, 1943;[14][15] the Dearborn Subway, on which work had been suspended during World War II, opened on February 25, 1951.[16] The subways were constructed with a secondary purpose of serving as bomb shelters, as evidenced by the close spacing of the support columns (a more extensive plan proposed replacing the entire elevated system with subways). The subways bypassed a number of tight curves and circuitous routings on the original elevated lines (Milwaukee trains, for example, originated on Chicago's northwest side but entered the Loop at the southwest corner), speeding service for many riders.

CTA assumes control

By the 1940s the financial condition of the "L", and of Chicago mass transit in general, had become too precarious to permit continued operation without subsidies, and the necessary steps were taken to enable a public takeover. In 1947, the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) acquired the assets of the Chicago Rapid Transit Company and the Chicago Surface Lines, operator of the city's streetcars. Over the next few years CTA modernized the "L", replacing wooden cars with new steel ones and closing lightly used branch lines and stations, many of which had been spaced only a quarter-mile apart.

Skip-stop service

Later, after assuming control of the "L", the CTA introduced an express service known as the A/B skip-stop service. Under this service, trains were designated as either "A" or "B" trains, and stations were alternately designated as "A" stations or "B" stations, with heavily used stations designated as both – "AB". "A" trains would only stop at "A" or "AB" stations, and "B" trains would only stop at "B" or "AB" stations. Station signage carried the station's skip-stop letter and was also color-coded by skip-stop type; "A" stations had red signage, "B" stations had green signage, and "AB" stations had blue signage. The system was designed to speed up lines by having trains skip stations while still allowing for frequent service at the heavily used "AB" stations. CTA first implemented A/B skip-stop service on the Lake Street Line (now part of the Green Line) in 1948, and the service proved effective as travel times were cut by a third. By the 1950s, the service was used throughout the system. All lines used the A/B skip-stop service between the 1950s and the 1990s with the exception of the Evanston and Skokie lines, which were suburban-only lines and did not justify skip-stop service. Also, the Congress and Douglas branches of what later became the Blue Line were designated as "A" and "B" respectively, as were the Englewood ("A") and Jackson Park ("B") branches of what later became the Green Line, so individual stops were not skipped while trains were serving those branches. As time went by, the time periods which employed skip-stop service gradually decreased, as the waits at "A" and "B" stations became increasingly longer during non-peak service. By the 1990s, use of the A/B skip-stop system was only used during rush hour service. Another problem was that trains skipping stations to save time still could not pass the train that was directly ahead, so skipping stations was not advantageous in all regards. In 1993, the CTA began to eliminate skip-stop service when it switched the southern branches of the Red and Green Lines to all stops. After this point, Green Line trains on the entire line stopped at all stations, and Red Line trains stopped at all stations south of Harrison. The elimination of A/B skip-stop service continued with the opening of the all-stop Orange Line and the conversion of the Brown Line to all-stop service. On April 28, 1995, the A/B skip-stop system was completely eliminated with the transfer of the O'Hare branch of the Blue Line and the Howard branch of the Red Line to all-stop service. The removal of skip-stop service resulted in some increases in travel times, and greatly increased ridership at former "A" and "B" stations.[17]

New rolling stock

The first air-conditioned cars were introduced in 1964, the last pre-World War II cars were retired in 1973. New lines were built in expressway medians, a technique implemented in Chicago and followed by other cities worldwide. The Congress branch, built in the median of the Eisenhower Expressway, replaced the Garfield Park "L" in 1958. The Dan Ryan line, built in the median of the Dan Ryan Expressway, opened on September 28, 1969,[18] followed by an extension of the Milwaukee elevated into the Kennedy Expressway in 1970.

The "L" today

At 102.8 miles (165.4 km),[1][note 1] the Chicago "L" is the fourth largest heavy rail rapid transit system in the United States in terms of route mileage. It runs over a total of 224.1 miles (360.7 km) of track.[1] Ridership had been remarkably stable for nearly 40 years after the CTA takeover despite declining mass transit usage nationwide, with an average of 594,000 riders boarding each weekday in 1960[19] and 577,000 in 1985. Due to the Loop Flood in 1992, ridership was at 418,000 that year[20] because CTA was forced to suspend operation for several weeks in both the State and Dearborn subways, used by the most heavily traveled lines.

Ridership is healthy and growth continues, but it has not been uniformly distributed. Use of North Side lines is heavy and continues to grow, while that of West Side and South Side lines tend to remain stable. Ridership on the North Side Brown Line, for instance, has increased 83% since 1979, necessitating a station reconstruction project to accommodate even longer trains.[21]

Annual traffic on the Howard branch of the Red Line, which reached 38.7 million in 2010 and 40.9 million in 2011, has exceeded the 1927 prewar peak of 38.5 million.[22] The section of the Blue Line between the Loop and Logan Square, which serves once-neglected but now bustling neighborhoods such as Wicker Park, Bucktown, and Palmer Square, has seen a 54% increase in weekday riders since 1992. On the other hand, weekday ridership on the South Side portion of the Green Line, which closed for two years for reconstruction starting in 1994, was 50,400 in 1978 but only 13,000 in 2006. Boardings at the 95th/Dan Ryan stop on the Red Line, though still among the system's busiest at 11,100 riders per weekday[23] as of February 2015, are less than half the peak volume in the 1980s. In 1976, three North Side "L" branches – what were then known as the Howard, Milwaukee, and Ravenswood lines − accounted for 42% of non-downtown boardings. Today (with the help of the Blue Line extension to O'Hare), they account for 58%.

The North Side (which has historically been the highest density area of the city) skew no doubt reflects the Chicago building boom between 2000 and 2010, which has focused primarily on North Side neighborhoods and downtown.[24] It may ease somewhat in the wake of the current high level of residential construction along the south lakefront. For example, ridership at the linked Roosevelt stops on the Green, Orange, and Red Lines,[25] which serve the burgeoning South Loop neighborhood, has tripled since 1992, with an average of 8,000 boardings per weekday. Patronage at the Cermak-Chinatown stop on the Red Line (4,000 weekday boardings) is at the highest level since the station opened in 1969. The 2003 Chicago Central Area Plan proposed construction of a Green Line station at Cermak, midway between Chinatown and the McCormick Place convention center, in expectation of continued density growth in the vicinity. This station opened in 2015.

As of mid-2006, the "L" accounted for 36% of the CTA's nearly 1.5 million weekday riders, with the remainder traveling on the extensive bus network. The rail system's ridership has increased over time. In 1926, the year of peak prewar rail usage, the "L" carried 229 million passengers – seemingly a formidable number, but actually less than 20% of the 1.16 billion Chicago transit patrons that year, most of whom rode the city's streetcars.[26] The shift to rail has continued in recent times. Since its low point in 1992 due to the Chicago Flood that closed subway tunnels in the downtown area, weekday "L" ridership has increased about 25%, while bus ridership has decreased by roughly a sixth.[27]

Currently, with two exceptions, all lines operate at all times except late nights. The exceptions are the Red Line and the Blue Line. which operate 24/7.[28][29] Prior to 1998, the Green Line, the Purple Line and the Douglas branch of the Blue Line also had 24 hour service.[30] In the years of private ownership, the South Side Elevated Railroad (now the South Side Elevated portion of the Green Line) provided 24 hour service, a major advantage when compared to Chicago's cable railroads which required daily overnight shutdown for cable maintenance.[31]

As of 2018, the "L" uses a flat fare of $2.50 for almost the entire system, the only exception being O'Hare International Airport on the Blue Line, at which passengers entering the station are charged a higher fare of $5.00 (passengers leaving the system at this station are not charged this higher fare).[32] The higher fare is being charged for what the CTA considers "premium-level" service to O'Hare.[33] Use of the Midway International Airport Station does not require this higher fare; it only requires the $2.50 regular fare.[32] The higher charge at O'Hare has been the source of some controversy in recent years, because of the CTA's plan to eliminate the exemption from the premium fare for airport workers, Transportation Security Administration workers, and airline workers.[33] After protests from those groups, the CTA extended the exemptions for six months.[34]

Renovation and expansion plans

The CTA's current capital improvement spending is focused on the Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project, Slow Zone Elimination, and the rehabilitation of the Red Line. In 2012, the CTA reopened the Green Line's Morgan station, and the Village of Skokie reopened the Yellow Line's Oakton station. Both stations were closed in 1948 after the CTA was created, and the original stations were demolished soon after.

The CTA is also actively studying a number of proposals for expanding "L" rail service, including the Circle Line and extensions to the Red, Orange, and Yellow Lines.[35] The State's capital budget proposal for fiscal year 2010 includes funding for "preliminary engineering" on the planned Circle Line, as well as funds for modernizing and replacing the system's aging railcars.[36]

In addition, CTA has studied numerous other proposals for expanded rail service, some of which may be implemented in the future.

Recent service improvements

Pink Line service began on June 25, 2006, though it did not involve any new tracks or stations. The Pink Line travels over what was formerly a branch of the Blue Line from the 54th/Cermak terminal in Cicero to the Polk station in Chicago. Pink Line trains then proceed via the Paulina Connector to the Lake Street branch of the Green Line and then clockwise around the Loop elevated via Lake-Wabash-Van Buren-Wells. (Douglas trains used the same route between April 4, 1954 and June 22, 1958 after the old Garfield Park "L" line was demolished to make way for the Eisenhower Expressway.)[37] The new route, which serves 22 stations, offers more frequent service for riders on both the Congress and Douglas branches. Pink Line trains can be scheduled independently of Blue Line trains, and run more frequently than the Douglas branch of the Blue Line did.[38]

The Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project enabled CTA to run eight-car trains on the Brown Line, and rebuilt stations to modern standards, including handicap accessibility.[39] Before the project, Brown Line platforms could only accommodate six-car trains, and increasing ridership led to uncomfortably crowded trains. After several years of construction, eight-car trains began to run at rush hour on the Brown Line in April 2008. The project was completed at the end of 2009, on time and on budget, with only minor punch list work remaining. The project's total cost is expected to be around $530 million.[40]

One of the largest reconstruction projects in the CTA's history, at a cost of $425 million, was the Red Line South reconstruction project. From May 19, 2013 through October 20, 2013, the project closed and rebuilt the entire Dan Ryan branch — replacing and rebuilding all the tracks, ties, ballast and drainage systems — from Cermak-Chinatown to 95th/Dan Ryan.[41] The station work involved renewing and improving eight stations, including new paint and lights, bus bridge improvements, new elevators at the Garfield, 63rd, and 87th stations and new roofs and canopies at some stations. "We are looking forward to providing our south Red Line customers with improved stations that are cleaner, brighter and better than they have been in years," said CTA President Forrest Claypool.[42]

Current capital improvements

In late 2007, trains were forced to operate at reduced speed over more than 22% of the system due to deteriorated track, structure, and other problems.[43] By October 2008, system-wide slow zones had been reduced to 9.1%[44] and by January 2010, total slow zones were reduced to 6.3%. CTA's Slow Zone Elimination Project is an ongoing effort to restore track work to conditions where trains no longer have to reduce speeds through deteriorating areas. The Loop received track work in 2012–2013. The Purple Line in Evanston received track work and viaduct replacement in 2011–2013. The Green Line Ashland branch received track work in 2013, prior to the Red Line Dan Ryan reconstruction.[45]

As of 2014, the CTA is investing in station and track upgrades on the Blue Line between Grand and O'Hare. This four year, $492 million project, will result in modernized stations (some of which were originally built in 1895), rebuilt track, faster service between O'Hare and the Loop, station platform replacement, subway water management, subway station water infiltration remediation, and improved access to some stations (by adding elevators).[46]

An extensive 4G wireless coverage was added to both Blue and Red Line subways, with the $32.5 million installation cost paid for by T-Mobile, Sprint, AT&T and Verizon.[47]

Planning future projects

All of the new rail service proposals under active consideration by CTA are currently undergoing Alternatives Analysis Studies.

These studies are the first step in a five-step process. This process is required by the Federal New Starts program,[48] which is an essential source of funding for CTA's expansion projects. CTA uses a series of "Screens" to develop a "Locally Preferred Alternative", which is submitted to the federal New Starts program.

It will likely be years before any of these projects is completed, as no project yet has a definite source of funding.[49]

Circle Line

The proposed Circle Line would form an "outer loop", traversing downtown via the State Street subway, then going southwest on the Orange Line and north along Ashland, before re-joining the subway at North/Clybourn or Clark/Division.[50] The Circle Line would connect several different Metra lines with the "L" system, and would facilitate transfers between existing CTA lines; these connections would be situated near the existing Metra and "L" lines' maximum load points.[51] CTA initiated official "Alternatives Analysis" planning for the Circle Line in 2005. The Circle Line concept garnered significant public interest and media coverage.[52][53]

Early conceptual planning divided the Circle Line into three segments.[54] Phase 1 would be a restoration of the dilapidated "Paulina Connector", a short (0.75 mi/1.2 km) track segment that links Ashland/Lake with Polk. This track section has since been restored and service on the 54th/Cermak branch was transferred to the Pink Line. Phase 2 would link 18th on the Pink Line to Ashland on the Orange Line, with a new elevated structure running through a large industrial area. Phase 3, the final phase, would link Ashland/Lake to North/Clybourn with a new subway running through the dense neighborhoods of West Town and Wicker Park. With the completion of all three phases, the perimeter area would be served by Circuit Line trains.[53]

In 2009, CTA released the results of its Alternatives Analysis Screen 3, in which it decided to begin early engineering work on Phase 2, due to its simple alignment through unpopulated areas and its relatively low cost (estimated at $1.1 billion).[55] Preliminary engineering work is now being performed on Phase 2. In addition to the new line, CTA plans to build four new stations as part of Phase 2, although three out of the four will be located along existing lines that the Circle Line will utilize. These will be at 18th/Clark, Cermak/Blue Island, Roosevelt/Paulina, and Congress/Paulina. 18th/Clark will be along the Orange Line in the Chinatown neighborhood, and will include a direct transfer connection to the Cermak/Chinatown station on the Red Line. Cermak/Blue Island will be located on the newly built elevated tracks in the Pilsen neighborhood. Roosevelt/Paulina will be located on the Pink Line in the Illinois Medical District. Finally, Congress/Paulina will be built above the Eisenhower Expressway, with a direct transfer connection to the Illinois Medical District station on the Blue Line. Existing stations will provide service near the United Center.[56]

Phase 3 was not implemented, and planning stopped after 2009.[53] Phase 3 ran through dense residential areas, so alignment must be considered carefully to avoid adversely impacting those neighborhoods. CTA estimated that Phase 3 would be far more costly than Phase 2 due to its being underground. After a number of alternate plans were evaluated, in 2009 CTA adopted the "locally preferred alternative" (LPA),[52] which stopped Circle Line work after Phase 2, and Phase 3 was relegated to a "long term vision".[53]

Line extensions

CTA is conducting Alternatives Analysis Studies of proposed extensions for the Red, Orange and Yellow Lines. Although these are three separate projects in three different areas of the city and suburbs, all three projects involve similar challenges of extending existing lines into underserved areas, so CTA has chosen to group the lines together into a larger program, so that analysis, engineering, and construction work can be done more cost-effectively through economies of scale.

Red Line extension

An extension of the Red Line would provide service from the current terminus at 95th/Dan Ryan to 130th Street, decreasing transit times for residents of the far South Side and relieving crowding and congestion at the current terminus.[57] CTA presented its locally preferred alternative at meetings in 2009. This consists of a new elevated rail line between 95th/Dan Ryan and a new terminal station at 130th Street, paralleling a Union Pacific Railroad line through the Far South Side neighborhoods of Washington Heights, Roseland, West Pullman, and Riverdale. In addition to the terminal station at 130th, three new stations would be built at 103rd, 111th, and Michigan. Basic engineering, along with an environmental impact statement, were underway in 2010.[58] Alignment commenting was opened in 2016.[59] A decision was announced on January 26, 2018, if the CTA can get the funding for the $2.3 billion extension, construction on the extension would begin in 2022 and would be completed in 2026.[60]

Orange Line extension

An extension of the Orange Line would provide transit service from the current terminus, Midway International Airport, to the Ford City Mall, which was originally meant to be the Orange Line's southern terminus when the line was planned in the 1980s.[61] This would alleviate congestion at the current Midway terminal. CTA presented its locally preferred alternative at meetings in 2009. This consists of a new elevated rail line that runs south from the Midway terminal along Belt Railway tracks, crosses Clearing Yard while heading southwest to Cicero Avenue, then runs south in the median of Cicero to a terminal on the east side of Cicero near 76th Street. Basic engineering, along with an environmental impact statement, were underway in 2010. The extension was cancelled.[62]

Yellow Line extension

An extension of the Yellow Line would provide transit service from the current terminus, at Dempster Street, to the corner of Old Orchard Road and the Edens Expressway, just west of the Westfield Old Orchard shopping center. CTA presented its locally preferred alternative at meetings in 2009. This consists of a new elevated rail line from Dempster north along a former rail right-of-way to the Edens Expressway, where the line will turn to the north and run along the east side of the expressway to a terminus at Old Orchard Road. Basic engineering, along with an environmental impact statement, were underway in 2010.[63] Unlike extensions to the Red and Orange Lines, the Yellow Line Extension had attracted significant community opposition from residents of Skokie, as well as parents of students at neighboring Niles North High School, on whose land the new line would be constructed. Residents and parents have cited concerns about noise, visual pollution, and crime. As a result, the extension was cancelled.[64]

Possible future projects

There are other possible future expansions, identified in various city and regional planning studies.[65][66] CTA has not begun official studies of these expansions, so it is unclear whether they will ever be implemented, or simply remain as visionary projects. They include:

- Clinton Street Subway, running through the West Loop, connecting the Red Line near North/Clybourn to the Red Line again, near Cermak-Chinatown. From North/Clybourn, the subway would run south along Larrabee Street, then under the Chicago River to Clinton Street in the West Loop. Running south under Clinton, the subway would pass Ogilvie Transportation Center and Union Station, with short connections to Metra trains. It would then continue south on Clinton until roughly 16th Street, where it would turn east, cross the river again, and rejoin the Red Line just north of the current Cermak-Chinatown stop. The estimated cost of this line was $3 billion, with no local funding source identified.[66][67]

- Airport Express service to O'Hare International Airport and Midway from a downtown terminal on State Street. On the 3200 series cars, black Midway and O'Hare destination signs exist, suggesting a possible Airport Express service, since the sign used for Express trains is written in a black background. A business plan prepared for CTA called for a private firm to manage the venture with service starting in 2008.[68] The project has been criticized as a boondoggle.[69] The custom-equipped, premium-fare trains would offer nonstop service at faster speeds than the current Blue and Orange Lines. Although the trains would not run on dedicated rails (construction of such tracks could cost more than $1.5 billion), several short sections of passing track built at stations would allow the express trains to pass Blue and Orange trains while they sit at those stations.[70] CTA has pledged $130 million and the city of Chicago $42 million toward the cost of the downtown station.[71] In comments posted to her blog in 2006, CTA chair Carole Brown said, "I would support premium rail service only if it brought significant new operating dollars, capital funding, or other efficiencies to CTA… The most compelling reason to proceed with the project is the opportunity to connect the Blue and Red subway tunnels," which are one block apart downtown.[72] In the meantime, CTA announced that due to cost overruns, it would only complete the shell of the Block 37 station; its president said "it would not make sense to completely build out the station or create the final tunnel connections until a partner is selected because final layout, technology and finishes are dependent on an operating plan."[73]

- Mid-City Transitway running around, rather than through the Chicago Loop. The line would follow the Cicero Avenue/Belt Line corridor (former Crosstown Expressway alignment) between the O'Hare branch of the Blue Line at Montrose and the Dan Ryan branch of the Red Line at 87th Street. It may be an "L" line, but busway and other options are being considered.

Numerous plans have been advanced over the years to reorganize downtown Chicago rapid transit service, originally with the intention of replacing the elevated Loop lines with subways. That idea has been largely abandoned as the city seems keen on keeping an elevated/subway mix. But there have been continued calls to improve transit within the city's greatly enlarged central core. At present the "L" does not provide direct service between the Metra commuter rail terminals in the West Loop and Michigan Avenue, the principal shopping district, nor does it offer convenient access to popular downtown destinations such as Navy Pier, Soldier Field, and McCormick Place. Plans for the Central Area Circulator, a $700 million downtown light rail system meant to remedy this, were shelved in 1995 for lack of funding. An underground line running along the lakeshore would connect some of the city's major tourist destinations, but this plan has not been widely discussed. Recognizing the cost and difficulty of implementing an all-rail solution, the Chicago Central Area Plan[74] advocated a mix of rail and bus improvements, the centerpiece of which was the West Loop Transportation Center, a multi-level subway to be constructed under Clinton Street from Congress Parkway to Lake Street. The top level would be a pedestrian mezzanine, buses would operate in the second level, rapid transit trains in the third level, and commuter/high-speed intercity trains in the bottom level. The rapid transit level would connect to the existing Blue Line subway at its north and south ends, making possible the "Blue Line loop", envisioned as an underground counterpart to the Loop elevated. Alternatively, this level might be occupied by the Clinton Street Subway. Among other advantages, the West Loop Transportation Center would provide a direct link between the "L" and the city's two busiest commuter rail terminals, Ogilvie Transportation Center and Union Station. The plan also proposed transitways along Carroll Avenue (a former rail right-of-way north of the main branch of the Chicago River) and under Monroe Street in the Loop, which earlier transit schemes had proposed as rail routes. The Carroll Avenue route would provide faster bus service between the commuter stations and the rapidly redeveloping Near North Side, with possible rail service later. These new busways would tie into the bus level of the West Loop Transportation Center.

Lines

Since 1993 "L" lines have been officially identified by color,[37] although older route names survive to some extent in CTA publications and popular usage to distinguish branches of longer lines. Stations are found throughout Chicago, as well as in the suburbs of Forest Park, Oak Park, Evanston, Wilmette, Cicero and Skokie.

- Red Line, consisting of the North Side Main Line, State Street Subway, and Dan Ryan Branch

- The Red Line is the busiest route, with 234,232 passenger boardings on an average weekday in 2013.[75] It includes 33 stations on its 21.8-mile (35 km) route, traveling from the Howard terminal on the city's north side, through downtown Chicago via the State Street subway, then down the Dan Ryan Expressway median to 95th/Dan Ryan on the South Side. Despite its length, the Red Line stops five miles (8 km) short of the city's southern border. Extension plans to 130th are currently being considered. The Red Line is one of two lines operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week and is the only CTA "L" line that goes to both Wrigley Field and Guaranteed Rate Field, the homes of Chicago's Major League Baseball teams, the Chicago Cubs and Chicago White Sox. Rail cars are stored at the Howard Yard on the north end of the line and at the 98th Yard at the south end.

- Blue Line, consisting of the O'Hare, Milwaukee-Dearborn Subway, and Congress branches

- The Blue Line extends from O'Hare International Airport through the Loop via the Milwaukee-Dearborn subway to the West Side. Trains travel to Des Plaines Avenue in Forest Park via the Eisenhower Expressway median. The route from O'Hare to Forest Park is 26.93 miles (43 km) long. The number of stations is 33. Until 1970 the northern section of the Blue Line terminated at Logan Square, during that time it was called the Milwaukee route after Milwaukee Avenue which ran parallel to it; in that year service was extended to Jefferson Park via the Kennedy Expressway median, and in 1984 to O'Hare. The Blue Line is the second-busiest, with 176,120 weekday boardings.[75] It operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- Brown Line or Ravenswood Line

- The Brown Line follows an 11.4-mile (18 km) route, between the Kimball terminal in Albany Park and the Loop in downtown Chicago. In 2013, the Brown Line had an average weekday ridership of 108,529.[75]

- Green Line, consisting of the Lake Street Elevated, South Side Main Line, and Ashland and East 63rd branches

- A completely elevated route utilizing the system's oldest segments (dating back to 1892), the Green Line extends 20.8 miles (33.5 km) with 30 stops between Forest Park and Oak Park (Harlem/Lake), through The Loop, to the South Side. South of the Garfield station the line splits into two branches, with trains terminating at Ashland/63rd in West Englewood and terminating at Cottage Grove/63rd in Woodlawn. The East 63rd branch formerly extended to Jackson Park, but the tracks east of Cottage Grove, which ran above 63rd Street, was demolished in the 1980s and 1997 due to structural problems and then demolished due to community demands. The average number of weekday boardings in 2013 was 68,230.[75]

- Orange Line or Midway Line

- The 13-mile (21 km) long Orange Line was constructed from 1987 until 1993 on existing railroad embankments and new concrete and steel elevated structure. It runs from a station adjacent to Midway International Airport on the Southwest Side to The Loop in downtown Chicago. Average weekday ridership in 2013 was 58,765.[75]

- Purple Line, consisting of the Evanston Shuttle and Evanston Express

- The Purple Line is a 3.9-mile (6 km) branch serving north suburban Evanston and Wilmette with express service to the Loop during weekday rush hours. The local service operates from the Linden terminal in Wilmette through Evanston to the Howard terminal on the north side of Chicago where it connects with the Red and Yellow lines. The weekday rush hour express service continues from Howard to the Loop, running nonstop on the four-track line used by the Red Line to Belmont station, then serving all Brown Line stops to the Loop. 2013 average weekday ridership was 42,673 passenger boardings.[75] The stops from Belmont to Chicago Avenue were added in the 1990s to relieve crowding on the Red and Brown lines.[76] The name "purple line" is a reference to nearby Northwestern University, with four stops (Davis, Foster, Noyes, and Central) located just two blocks west of the University campus.

- Pink Line consisting of the Douglas Branch and Paulina Connector

- The Pink Line is a 11.2-mile (18 km) rerouting of former Blue Line Douglas Park branch trains from 54th/Cermak in Cicero via the previously non-revenue Paulina Connector and the Green Line on Lake Street to the Loop. Its average weekday ridership in 2013 was 31,572.[75] While still an extension of the original Douglas Park branch, the line ran to Oak Park Avenue in Berwyn, 2.1 miles (3.4 km) west of its current terminal point. In 1952 service on the portion of the line west of 54th Avenue was closed and over the next decade the stations were demolished and the tracks were also demolished. The street level right-of-way is used to this day as a miles-long parking lot, locally known as the " "L" Strip".[77]

- Yellow Line, or Skokie Swift

- The Yellow Line is a 4.7-mile (8 km) three station line that runs from the Howard Street terminal to Skokie terminal in north suburban Skokie. The Yellow Line is the only "L" route that does not provide direct service to the Loop. This line was originally part of the North Shore Line's rail service, and was acquired by the CTA in the 1960s. The Yellow Line previously operated as a nonstop shuttle, until the downtown Skokie station Oakton–Skokie opened on April 30, 2012.[78] Other plans in consideration are to extend the line from its current Dempster Street terminus to Old Orchard via an elevated right of way and the construction of an infill station in Evanston. Its average weekday ridership in 2013 was 6,338 passenger boardings.[75]

- The Loop

- Brown, Green, Orange, Pink, and Purple Line Express trains serve downtown Chicago via the Loop elevated. The Loop's eight stations average 72,843 weekday boardings. The Orange Line, Purple Line and the Pink Line run clockwise, the Brown Line runs counter-clockwise. The Green Line is the Loop's only through service; the other four lines circle the Loop and return to their starting points. The Loop forms a rectangle roughly 0.4 miles (650 m long) east-to-west and 0.6 miles (960 m) long north-to-south. The loop crossing at Lake and Wells has been described in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world's busiest railroad crossing.

Rolling stock

The CTA operates over 1,350 "L" cars,[1] divided among three series, some of which are permanently coupled into married pairs. All cars on the system utilize 600 volt direct current power delivered through a third rail. The new 5000-series cars are equipped with alternating current propulsion systems and have inverters on board to convert the DC power to AC power. The older cars use DC motors.

The 2600-series was built from 1981 until 1987 by the Budd Company of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After the completion of the order of the 2600-series cars, Budd changed its name to Transit America and ceased production of railcars. With 503 cars in operation, the 2600-series is the largest of the three series of "L" cars in operation, The cars were rebuilt by Alstom of Hornell, New York from 1999 until 2002.

The 3200-series, was built from 1992 until 1994 by Morrison-Knudsen of Hornell, New York. These cars have fluted, stainless steel sides similar to the now-retired 2200-series.

The newest series of train cars, the 5000-series, feature AC propulsion, security cameras, and aisle-facing seating.[79]

Nickname

The Chicago rapid-transit system is officially nicknamed the "L".[80] This name for the CTA rail system applies to the whole system: its elevated, subway, at-grade, and open-cut segments. The use of the nickname dates from the earliest days of the elevated railroads. Newspapers of the late 1880s referred to proposed elevated railroads in Chicago as "'L' roads."[81] The first route to be constructed, the Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad gained the nickname "Alley Elevated", or "Alley L" during its planning and construction,[82] a term that was widely used by 1893, less than a year after the line opened.[83][84]

In discussing various stylings of "Loop" and "L" in Destination Loop: The Story of Rapid Transit Railroading in and around Chicago (1982), author Brian J. Cudahy quotes a passage from The Neon Wilderness (1947) by Chicago author Nelson Algren: "beneath the curved steel of the El, beneath the endless ties." Cudahy then comments, "Note that in the quotation above ... it says 'El' to mean 'elevated rapid transit railroad.' We trust that this usage can be ascribed to a publisher's editor in New York or some other east coast city; in Chicago the same expression is routinely rendered 'L'."

As used by CTA, the name is rendered as the capital letter 'L', in single quotation marks. "L" (with double quotation marks) was often used by CTA predecessors such as the Chicago Rapid Transit Company; however, the CTA uses single quotation marks (') on some printed materials and signs rather than double. In Chicago, the term "subway" is only applied to the sections of the Red and Blue Lines that are actually underground and is not applied to the entire system as a whole, as in New York City where both the elevated and underground portions make up the New York City Subway.

Security and safety

The CTA rail cars have generally been secure and safe but in addition to general security issues on the CTA, there were calls to improve CTA's emergency response and communications procedures.[85] CTA has also had incidents where operators apparently overrode automatic train stops on red signals, such as the 1977 collision at Wabash and Lake, when four cars of a Lake-Dan Ryan train fell from the elevated structure, killing 11,[86] two minor incidents in 2001,[87] and two more in 2008, the more serious involving a Green Line train that derailed and straddled the split in the elevated structure at the 59th Street junction between the Ashland and East 63rd Street branches,[88] and a minor one near 95th Street on the Red line.[89] In 2014, the O'Hare station train crash occurred when a Blue Line train overran a bumper at the airport station and ascended up an escalator.

In 2002, 25-year-old Joseph Konopka, self-styled as "Dr. Chaos", was arrested by Chicago police for hoarding potassium cyanide and sodium cyanide in a Chicago Transit Authority storeroom in the Chicago "L" Blue Line subway. Konopka had picked the original locks on several doors in the tunnels, then changed the locks so that he could access the rarely used storage rooms freely.[90][91][92]

Recent studies have highlighted the Belmont and 95th stops on the Red Lines being the "most dangerous." [93][94]

In popular culture

Movies and television shows use establishing shots to orient audiences to the location. For media set in Chicago, the "L" is a common feature because it is a distinctive part of the city. Some of the more prominent films which have used such setup footage include:

- The Sting (1973)

- The Blues Brothers (1980).[95]

- Risky Business (1983) features the "L" in several erotic sequences

- Code of Silence (1985)

- Running Scared (1986) shows a car chase taking place on the "L" tracks. The sounds of the "L" are also distinctive and are therefore also used to establish location

- Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987)

- The Fugitive (1993), which also contained a short scene inside of an "L" train

- While You Were Sleeping (1995) includes a main character, Lucy, who works as an "L" fare collector

- Shall We Dance (2004 film), in which Richard Gere learns to dance with Jennifer Lopez by the light of the "L'

- Divergent features the "L" as the method of transportation around the city and plays a key role in certain situations. In Allegiant several of the main characters take the "L" to near the John Hancock Tower to scatter Tris' ashes. These films portray futuristic versions of current train models.

In television:

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 This figure comes from the sum of the following figures from the accompanying reference (i.e. "CTA Facts at a Glance". CTA. Spring 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2015. ): 35.8 miles of elevated route, 35.0 miles at grade level, 20.6 miles on embankments, and 11.4 miles of subway.

- ↑ The four other rapid transit systems in the U.S. that provide 24-hour service are the New York City Subway, Staten Island Railway, PATH, and Philadelphia's PATCO Speedline.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "CTA Facts at a Glance". CTA. Spring 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Annual Ridership Report: Calendar Year 2015" (PDF). Transitchicago.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-29. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ↑ "Annual Ridership Report : Calendar Year 2016" (PDF). Transitchicago.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ "Our Services". Chicago Transit Authority. Archived from the original on 2011-08-12. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ↑ "American Public Transportation Rider Reports Year End 2014" (PDF). Apta.com. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Cudahy, Brian J. (1982). Destination Loop: The Story of Rapid Transit Railroading in and around Chicago. Brattleboro, VT: S. Greene Press. ISBN 978-0-8289-0480-3.

- ↑ Garfield, Graham (8 November 2008). "Frequently Asked Questions". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ↑ McClendon, Dennis. "L". Encyclopedia of Chicago. ChicagoHistory.org. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ "Annual Ridership Report: Calendar Year 2014" (PDF). Chicago Transit Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ Leroux, Charles (15 September 2005). "The People Have Spoken: Here Are the 7 Wonders of Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ↑ "Running on the "L."". Chicago Daily Tribune. 7 June 1892. p. 9.

- 1 2 Borzo, Greg (2007). The Chicago "L". Chicago: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 23, 43. ISBN 978-0-7385-5100-5.

- ↑ "Jackson Park". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ Shinnick, William (October 17, 1943). "Chicago Underground—A Subway at Last!". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. C1.

- ↑ "Subway Opened by Mayor; Big Crowd Attends". Chicago Daily Tribune. October 17, 1943. p. 3.

- ↑ Buck, Thomas (February 25, 1951). "New Subway to Northwest Side Opened". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 1.

- ↑ "A/B Skip-Stop Express Service". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ↑ Buck, Thomas (September 28, 1969). "Ryan Rail Service Starts Today". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 22.

- ↑ Chicago Transit Authority, "Rail System – Nov. 1980 traffic," Table V, OP-x81085, 5-22-81

- ↑ Chicago Transit Authority, "Rail System – Weekday Entering Traffic Trends," PSP-x01013, 8-16-01

- ↑ "About the Brown Line". CTA. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ CTA, "Rail System – Annual Traffic: Originating passengers only," OP-x79231, 10-01-79

- ↑ "Annual Ridership Report : Calendar Year 2015" (PDF). Transitchicago.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-04. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ Pearce, Barry. "Movin' Out". North Shore Magazine. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ The Roosevelt elevated stop on the Orange and Green Lines, which opened in 1994, is connected to the Roosevelt Red Line subway stop by a pedestrian passage, so CTA reports the two as a single station. Ridership in 1992 is for the subway stop only.

- ↑ Condit, Carl W., Chicago 1930–70: Building, Planning, and Urban Technology (1974), Table 7

- ↑ 1992 figures from CTA, "1992 Ridership Review," Technical Report SP93-05; November 2005 figures from CTA website previously cited. Comparison may not be precise; 1992 figures were an annual average, while November 2005 reflected a single month, though one which CTA often uses as a benchmark.

- ↑ "CTA Red Line - Route Guide (Map, Alerts and Schedules/Timetables)". Transit Chicago. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ "CTA Blue Line - Route Guide (Map, Alerts and Schedules/Timetables)". Transit Chicago. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ Bushell, Chris, ed. Jane's Urban Transport Systems 1995–96. Surrey, United Kingdom: Jane's Information Group; 1995. p78.

- ↑ Cudahy, Brian J. Destination Loop. Brattleboro, Vermont: Stephen Greene Press; 1982. p.13

- 1 2 "Rapid Transit Trains to Chicago Airports (O'Hare & Midway) - CTA". Transit Chicago. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- 1 2 "CTA ends break in fare surcharge for Blue Line trips from O'Hare - Chicago Tribune". 4 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- ↑ "CTA lands deal for O'Hare workers on Blue Line". Articles.chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑

- ↑ "Illinois Capital Budget: Fiscal Year 2010" (PDF). Authority of the State of Illinois. March 18, 2009. p. 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- 1 2 Garfield, Graham. "Chronologies – Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) (1947–present)". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ "West Side/West Suburban Corridor Service Enhancements". CTA. Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. Retrieved September 5, 2006.

- ↑ "Capacity Expansion". CTA. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ↑ "CTA 2009 Budget Recommendations, p. 34" (PDF). Transitchicago.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ "Red Line South Reconstruction Project". October 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ "Chicago Transit Authority awards contract for Red Line South project". 19 November 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ CTA President Ron Huberman, "Transforming the CTA" presentation Archived 2012-03-30 at the Wayback Machine., slide 17; a current slow zone map can be found on the CTA's website.

- ↑ "2009 Budget Recommendations" (PDF). Chicago Transit Authority. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-25. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Putting Rapid Back in Transit". June 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ "Your New Blue: Station, Track & Infrastructure Improvements". Transitchicago.vom. 29 May 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Hilkevitch, Jon (January 30, 2015). "4G wireless coming to CTA subways later this year". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ The FTA's website Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. provides a detailed description of this process.

- ↑ "RedEye". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "Screen 2 Preliminary Findings: Bus Rapid Transit" (PDF). Circle Line Alternatives Analysis Study. Chicago Transit Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-30. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Chicago Transit Authority : Circle Line Alternatives Analysis Study Screen 2 Public Involvement : Responses to Public Comments and Questions" (PDF). 24 February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- 1 2 Circle Line Alternatives Analysis Study (PDF), Chicago Transit Authority, September 29, 2009, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-08, retrieved October 1, 2017

- 1 2 3 4 Zotti, Ed; Chicago Central Area Committee (August 17, 2016), The Case for Rail Transit Expansion in the Chicago Central Area (PDF), NURail Center, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, pp. C-6 to C-7

- ↑ "Circle Line Phasing Plan". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Screen 3 Public Involvement: Responses to Public Comments and Questions" (PDF). Circle Line Alternatives Analysis Study. CTA. December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-30. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Circle Line Alternatives Analysis Study Screen 3 Responses to Public Comments and Questions" (PDF). CTA. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Red Line Extension Locally Preferred Alternative Report" (PDF). CTA. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Red Line Extension Project". CTA. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ "CTA confirms Red Line extension south to 130th Street". Chicago.curbed.com. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ "CTA reveals route, new stations for South Side Red Line extension". chicago.curbed.com.

- ↑ Jon Hilkevitch. "Signs mark growth of CTA" Chicago Tribune, 30 October 2006.

- ↑ https://www.transitchicago.com/orangeeis/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Yellow Line Extension Project". CTA. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ https://www.transitchicago.com/yelloweis/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Garfield, Graham. "Destination 2020". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- 1 2 "Transportation" (PDF). Chicago Central Area ACTION Plan. City of Chicago. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ↑ Mccarron, John (April 6, 2009). "A $6 billion hole in the ground". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ PB Consult, Inc., Express Airport Train Service – Business Plan, Final Report, September 22, 2006

- ↑ Hinz, Greg (August 1, 2005). ""CTA's money pit: Big bucks, small bang for agency's planned express line to O'Hare,"". Crain's Chicago Business.

- ↑ "FindArticles.com - CBSi". findarticles.com. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ Hilkevitch, Jon, "Want a 1st-class ticket to airport? CTA plan would let private company run premium – and eventually express – rail service to O'Hare and Midway," Chicago Tribune, October 4, 2006

- ↑ Brown, Carole, Ask Carole, "Subway tunnel connections and airport service," Oct. 5, 2006, accessed Oct. 7, 2006. For illustration of Red-Blue line tunnel connection, see Chicago Transit Authority, Transit at a Crossroads: President's 2007 Budget Recommendations, p. 14, accessed Oct. 16, 2006 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- ↑ "CTA To Seek Private Sector Partners for Airport Express Service" (Press release). CTA. June 11, 2008. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008.

- ↑ City of Chicago, "Chicago Central Area Plan: Preparing the Central City for the 21st Century – Draft Final Report to the Chicago Plan Commission", May 2003, accessed Sept. 1, 2006. For West Loop Transportation Center details, see pp. 61ff Archived 2004-02-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Annual Ridership Report: Calendar Year 2013" (PDF). Chicago Transit Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-27. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ↑ "Countdown To A New Brown - About the Brown Line". ctabrownline.com. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ "Chicago '"L"'.org: Stations – Oak Park". Chicago-l.org. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ↑ Dorfman, Daniel (August 8, 2011). "Businesses Eagerly Await New CTA Station". SkokiePatch. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ↑ "CTA to Issue Bonds to Complete Purchase of New Rail Cars" (Press release). CTA. February 10, 2010. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ ""L"". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ↑ "Why not an "L" road? A question that is interesting west-siders". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1887-10-30.

- ↑ "Controls the Alley "L": The Chicago City Railway Company pays $500 for an interest". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1890-01-19. p. 5.

- ↑ Ralph, Julian (1893). Harper's Chicago and the World's Fair. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers. p. 143.

- ↑ Stevens, Charles McClellan (1893). The Adventures of Uncle Jeremiah and Family at the Great Fair. Chicago: Laird & Lee Publishers. p. 33.

- ↑ E.g. "Daley Challenges CTA to Strengthen Emergency Response Procedures" (Press release). City of Chicago. April 21, 2008.

- ↑ Garfield, Graham. "The Loop Crash". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ National Transportation Safety Board (September 5, 2002). "Two Rear-End Collisions Involving Chicago Transit Authority Rapid Transit Trains at Chicago, Illinois June 17 and August 3, 2001" (PDF).

- ↑ "Operator error likely cause in CTA derailment". ABC7 News. May 29, 2008.

- ↑ "CTA investigates Red Line derailment". ABC7 News. June 3, 2008.

- ↑ Barton, Gina (June 17, 2004). "'Dr. Chaos' gets 10 more years for crime spree". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ↑ Held, Tom (March 14, 2002). "Judge calls 'Dr. Chaos' a true danger: Cyanide suspect waives hearing, stays in custody". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ↑ Staff (June 1, 2005). "Wisconsin: Ruling Favors 'Dr. Chaos'". New York Times. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Data Reveals Most Crime-Ridden CTA Stations". Nbcchicago.com. January 30, 2014. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ↑ "Chicago's Most Dangerous 'L' Stops". August 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Chicago '"L"'.org: Multimedia". Chicago-l.org. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

Further reading

External links

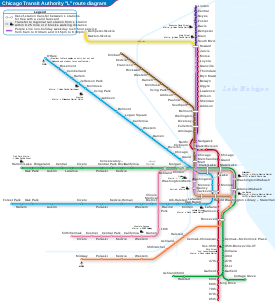

Route map:

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Chicago Transit Authority – operates CTA buses and "L" trains

- Ride the Rails – Interactive ride of the Chicago "L"

- Chicago-L.org – an unofficial, extensive fan site

- CTA Tattler – Daily blog of "L" stories

- ForgottenChicago.com – Forgotten Chicago, "Our Historic Subway Stations".

- Network map (real-distance)