Eugenics in the United States

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population,[2][3] played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States prior to its involvement in World War II.[4]

Eugenics was practiced in the United States many years before eugenics programs in Nazi Germany,[5] which were largely inspired by the previous American work.[6][7][8] Stefan Kühl has documented the consensus between Nazi race policies and those of eugenicists in other countries, including the United States, and points out that eugenicists understood Nazi policies and measures as the realization of their goals and demands.[9]

During the Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th century, eugenics was considered a method of preserving and improving the dominant groups in the population; it is now generally associated with racist and nativist elements, as the movement was to some extent a reaction to a change in emigration from Europe, rather than scientific genetics.[10]

History

Early proponents

The American eugenics movement was rooted in the biological determinist ideas of Sir Francis Galton, which originated in the 1880s. Galton studied the upper classes of Britain, and arrived at the conclusion that their social positions were due to a superior genetic makeup.[11] Early proponents of eugenics believed that, through selective breeding, the human species should direct its own evolution. They tended to believe in the genetic superiority of Nordic, Germanic and Anglo-Saxon peoples; supported strict immigration and anti-miscegenation laws; and supported the forcible sterilization of the poor, disabled and "immoral".[12] Eugenics was also supported by African Americans intellectuals such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Thomas Wyatt Turner, and many academics at Tuskegee University, Howard University, and Hampton University; however, they believed the best blacks were as good as the best whites and "The Talented Tenth" of all races should mix.[13] W. E. B. Du Bois believed "only fit blacks should procreate to eradicate the race's heritage of moral iniquity."[13][14]

The American eugenics movement received extensive funding from various corporate foundations including the Carnegie Institution, Rockefeller Foundation, and the Harriman railroad fortune.[7] In 1906 J.H. Kellogg provided funding to help found the Race Betterment Foundation in Battle Creek, Michigan.[11] The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) was founded in Cold Spring Harbor, New York in 1911 by the renowned biologist Charles B. Davenport, using money from both the Harriman railroad fortune and the Carnegie Institution. As late as the 1920s, the ERO was one of the leading organizations in the American eugenics movement.[11][15] In years to come, the ERO collected a mass of family pedigrees and concluded that those who were unfit came from economically and socially poor backgrounds. Eugenicists such as Davenport, the psychologist Henry H. Goddard, Harry H. Laughlin, and the conservationist Madison Grant (all well respected in their time) began to lobby for various solutions to the problem of the "unfit". Davenport favored immigration restriction and sterilization as primary methods; Goddard favored segregation in his The Kallikak Family; Grant favored all of the above and more, even entertaining the idea of extermination.[16] The Eugenics Record Office later became the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Eugenics was widely accepted in the U.S. academic community.[7] By 1928, there were 376 separate university courses in some of the United States' leading schools, enrolling more than 20,000 students, which included eugenics in the curriculum.[17] It did, however, have scientific detractors (notably, Thomas Hunt Morgan, one of the few Mendelians to explicitly criticize eugenics), though most of these focused more on what they considered the crude methodology of eugenicists, and the characterization of almost every human characteristic as being hereditary, rather than the idea of eugenics itself.[18]

By 1910, there was a large and dynamic network of scientists, reformers, and professionals engaged in national eugenics projects and actively promoting eugenic legislation. The American Breeder's Association was the first eugenic body in the U.S., established in 1906 under the direction of biologist Charles B. Davenport. The ABA was formed specifically to "investigate and report on heredity in the human race, and emphasize the value of superior blood and the menace to society of inferior blood." Membership included Alexander Graham Bell, Stanford president David Starr Jordan and Luther Burbank.[19][20] The American Association for the Study and Prevention of Infant Mortality was one of the first organizations to begin investigating infant mortality rates in terms of eugenics.[21] They promoted government intervention in attempts to promote the health of future citizens.[22]

Several feminist reformers advocated an agenda of eugenic legal reform. The National Federation of Women's Clubs, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, and the National League of Women Voters were among the variety of state and local feminist organization that at some point lobbied for eugenic reforms.[23]

One of the most prominent feminists to champion the eugenic agenda was Margaret Sanger, the leader of the American birth control movement. Margaret Sanger saw birth control as a means to prevent unwanted children from being born into a disadvantaged life, and incorporated the language of eugenics to advance the movement.[24][25] Sanger also sought to discourage the reproduction of persons who, it was believed, would pass on mental disease or serious physical defects. She advocated sterilization in cases where the subject was unable to use birth control.[24] She rejected euthanasia.[26] For Sanger, it was individual women and not the state who should determine whether or not to have a child.[27][28]

In the Deep South, women's associations played an important role in rallying support for eugenic legal reform. Eugenicists recognized the political and social influence of southern clubwomen in their communities, and used them to help implement eugenics across the region.[29] Between 1915 and 1920, federated women's clubs in every state of the Deep South had a critical role in establishing public eugenic institutions that were segregated by sex.[30] For example, the Legislative Committee of the Florida State Federation of Women's Clubs successfully lobbied to institute a eugenic institution for the mentally retarded that was segregated by sex.[31] Their aim was to separate mentally retarded men and women to prevent them from breeding more "feebleminded" individuals.

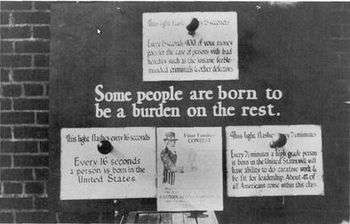

Public acceptance in the U.S. was the reason eugenic legislation was passed. Almost 19 million people attended the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, open for 10 months from 20 February to 4 December 1915.[32][33] The PPIE was a fair devoted to extolling the virtues of a rapidly progressing nation, featuring new developments in science, agriculture, manufacturing and technology. A subject that received a large amount of time and space was that of the developments concerning health and disease, particularly the areas of tropical medicine and race betterment (tropical medicine being the combined study of bacteriology, parasitology and entomology while racial betterment being the promotion of eugenic studies). Having these areas so closely intertwined, it seemed that they were both categorized in the main theme of the fair, the advancement of civilization. Thus in the public eye, the seemingly contradictory areas of study were both represented under progressive banners of improvement and were made to seem like plausible courses of action to better American society.[34]

Beginning with Connecticut in 1896, many states enacted marriage laws with eugenic criteria, prohibiting anyone who was "epileptic, imbecile or feeble-minded"[35] from marrying.[36]

The first state to introduce a compulsory sterilization bill was Michigan, in 1897 but the proposed law failed to garner enough votes by legislators to be adopted. Eight years later Pennsylvania's state legislators passed a sterilization bill that was vetoed by the governor. Indiana became the first state to enact sterilization legislation in 1907,[37] followed closely by Washington and California in 1909. Sterilization rates across the country were relatively low (California being the sole exception) until the 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell which legitimized the forced sterilization of patients at a Virginia home for the mentally retarded. The number of sterilizations performed per year increased until another Supreme Court case, Skinner v. Oklahoma, 1942, complicated the legal situation by ruling against sterilization of criminals if the equal protection clause of the constitution was violated. That is, if sterilization was to be performed, then it could not exempt white-collar criminals.[38] The state of California was at the vanguard of the American eugenics movement, performing about 20,000 sterilizations or one third of the 60,000 nationwide from 1909 up until the 1960s.[39]

While California had the highest number of sterilizations, North Carolina's eugenics program which operated from 1933 to 1977, was the most aggressive of the 32 states that had eugenics programs.[40] An IQ of 70 or lower meant sterilization was appropriate in North Carolina.[41] The North Carolina Eugenics Board almost always approved proposals brought before them by local welfare boards.[41] Of all states, only North Carolina gave social workers the power to designate people for sterilization.[40] "Here, at last, was a method of preventing unwanted pregnancies by an acceptable, practical, and inexpensive method," wrote Wallace Kuralt in the March 1967 journal of the N.C. Board of Public Welfare. "The poor readily adopted the new techniques for birth control."[41]

Immigration restrictions

The Immigration Restriction League was the first American entity associated officially with eugenics. Founded in 1894 by three recent Harvard University graduates, the League sought to bar what it considered inferior races from entering America and diluting what it saw as the superior American racial stock (upper class Northerners of Anglo-Saxon heritage). They felt that social and sexual involvement with these less-evolved and less-civilized races would pose a biological threat to the American population. The League lobbied for a literacy test for immigrants, based on the belief that literacy rates were low among "inferior races". Literacy test bills were vetoed by Presidents in 1897, 1913 and 1915; eventually, President Wilson's second veto was overruled by Congress in 1917. Membership in the League included: A. Lawrence Lowell, president of Harvard, William DeWitt Hyde, president of Bowdoin College, James T. Young, director of Wharton School and David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University.[42]

The League allied themselves with the American Breeder's Association to gain influence and further its goals and in 1909 established a Committee on Eugenics chaired by David Starr Jordan with members Charles Davenport, Alexander Graham Bell, Vernon Kellogg, Luther Burbank, William Ernest Castle, Adolf Meyer, H. J. Webber and Friedrich Woods. The ABA's immigration legislation committee, formed in 1911 and headed by League's founder Prescott F. Hall, formalized the committee's already strong relationship with the Immigration Restriction League. They also founded the Eugenics Record Office, which was headed by Harry H. Laughlin.[43] In their mission statement, they wrote:

Society must protect itself; as it claims the right to deprive the murderer of his life so it may also annihilate the hideous serpent of hopelessly vicious protoplasm. Here is where appropriate legislation will aid in eugenics and creating a healthier, saner society in the future.[43]

Money from the Harriman railroad fortune was also given to local charities, in order to find immigrants from specific ethnic groups and deport, confine, or forcibly sterilize them.[7]

With the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, eugenicists for the first time played an important role in the Congressional debate as expert advisers on the threat of "inferior stock" from eastern and southern Europe.[44] The new act, inspired by the eugenic belief in the racial superiority of "old stock" white Americans as members of the "Nordic race" (a form of white supremacy), strengthened the position of existing laws prohibiting race-mixing.[45] Eugenic considerations also lay behind the adoption of incest laws in much of the U.S. and were used to justify many anti-miscegenation laws.[46]

Stephen Jay Gould asserted that restrictions on immigration passed in the United States during the 1920s (and overhauled in 1965 with the Immigration and Nationality Act) were motivated by the goals of eugenics. During the early 20th century, the United States and Canada began to receive far higher numbers of Southern and Eastern European immigrants. Influential eugenicists like Lothrop Stoddard and Harry Laughlin (who was appointed as an expert witness for the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in 1920) presented arguments they would pollute the national gene pool if their numbers went unrestricted.[47][48] It has been argued that this stirred both Canada and the United States into passing laws creating a hierarchy of nationalities, rating them from the most desirable Anglo-Saxon and Nordic peoples to the Chinese and Japanese immigrants, who were almost completely banned from entering the country.[45][49]

Unfit vs. fit individuals

Both class and race factored into eugenic definitions of "fit" and "unfit." By using intelligence testing, American eugenicists asserted that social mobility was indicative of one's genetic fitness.[50] This reaffirmed the existing class and racial hierarchies and explained why the upper-to-middle class was predominantly white. Middle-to-upper class status was a marker of "superior strains."[31] In contrast, eugenicists believed poverty to be a characteristic of genetic inferiority, which meant that those deemed "unfit" were predominantly of the lower classes.[31]

Because class status designated some more fit than others, eugenicists treated upper and lower class women differently. Positive eugenicists, who promoted procreation among the fittest in society, encouraged middle class women to bear more children. Between 1900 and 1960, Eugenicists appealed to middle class white women to become more "family minded," and to help better the race.[51] To this end, eugenicists often denied middle and upper class women sterilization and birth control.[52]

Since poverty was associated with prostitution and "mental idiocy," women of the lower classes were the first to be deemed "unfit" and "promiscuous."[31]

Compulsory sterilization

In 1907, Indiana passed the first eugenics-based compulsory sterilization law in the world. Thirty U.S. states would soon follow their lead.[53][54] Although the law was overturned by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1921,[55] the U.S. Supreme Court, in Buck v. Bell, upheld the constitutionality of the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924, allowing for the compulsory sterilization of patients of state mental institutions in 1927.[56]

Some states sterilized "imbeciles" for much of the 20th century. Although compulsory sterilization is now considered an abuse of human rights, Buck v. Bell was never overturned, and Virginia did not repeal its sterilization law until 1974.[57] The most significant era of eugenic sterilization was between 1907 and 1963, when over 64,000 individuals were forcibly sterilized under eugenic legislation in the United States.[58] Beginning around 1930, there was a steady increase in the percentage of women sterilized, and in a few states only young women were sterilized. From 1930 to the 1960s, sterilizations were performed on many more institutionalized women than men.[31] By 1961, 61 percent of the 62,162 total eugenic sterilizations in the United States were performed on women.[31] A favorable report on the results of sterilization in California, the state with the most sterilizations by far, was published in book form by the biologist Paul Popenoe and was widely cited by the Nazi government as evidence that wide-reaching sterilization programs were feasible and humane.[59][60]

Men and women were compulsorily sterilized for different reasons. Men were sterilized to treat their aggression and to eliminate their criminal behavior, while women were sterilized to control the results of their sexuality.[31] Since women bore children, eugenicists held women more accountable than men for the reproduction of the less "desirable" members of society.[31] Eugenicists therefore predominantly targeted women in their efforts to regulate the birth rate, to "protect" white racial health, and weed out the "defectives" of society.[31]

A 1937 Fortune magazine poll found that 2/3 of respondents supported eugenic sterilization of "mental defectives", 63% supported sterilization of criminals, and only 15% opposed both.[61][62]

In the 1970s, several activists and women's rights groups discovered several physicians to be performing coerced sterilizations of specific ethnic groups of society. All were abuses of poor, nonwhite, or mentally retarded women, while no abuses against white or middle-class women were recorded.[63] Several court cases such as Madrigal v. Quilligan, a class action suit regarding forced or coerced postpartum sterilization of Latina women following cesarean sections, and Relf v. Weinberger,[64] the sterilization of two young black girls by tricking their illiterate mother into signing a waiver, helped bring to light some of the widespread abuses of sterilization supported by federal funds.[65][66]

After World War II, Dr. Clarence Gamble revived the eugenics movement in the United States through sterilization. Dr. Gamble supported the eugenics movement throughout his life. He worked as a researcher at Harvard Medical school and was well off financially, as the Procter and Gamble fortune was inherited by him. Gamble, a proponent of birth control, contributed to the founding of public birth control clinics. These were the first public clinics in the United States. Until the 1960's and 1970's, Gamble's ideal form of eugenics, sterilization, was seen in various cases. Doctors told mothers that their daughters needed shots, but they were actually sterilizing them. Hispanic women were often sterilized due to the fact that they could not read the consent forms that doctors had given them. Poorer white people, African Americans, and Native American people were also targeted for forced sterilization.[67]

The number of eugenic sterilizations is agreed upon by most scholars and journalists. They claim that there were 64,000 cases of eugenic sterilization in the United States, but this number does not take into account the sterilizations that took place after 1963. Around this time was when women from different minority groups were singled out for sterilization. If the sterilizations after 1963 are taken into account, the number of eugenic sterilizations in the United States increases to 80,000. Half of these sterilizations took place after World War II. Sterilization still occurs today, in some states, drug addicts can get paid to be sterilized. Eugenic sterilization programs before World War II were mostly conducted on prisoners, or people in mental hospitals. After the war, eugenic sterilization was aimed more towards poor people and minorities. There were even judges who would force people on parole to be sterilized. People supported this revival of eugenic sterilizations because they thought it would help bring an end to some issues, like poverty and mental illness. Supporters also thought that these programs would save taxpayer money and boost the economy.[68]

In 1972, United States Senate committee testimony brought to light that at least 2,000 involuntary sterilizations had been performed on poor black women without their consent or knowledge.[69] An investigation revealed that the surgeries were all performed in the South, and were all performed on black welfare mothers with multiple children.[69] Testimony revealed that many of these women were threatened with an end to their welfare benefits until they consented to sterilization.[69] These surgeries were instances of sterilization abuse, a term applied to any sterilization performed without the consent or knowledge of the recipient, or in which the recipient is pressured into accepting the surgery. Because the funds used to carry out the surgeries came from the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity, the sterilization abuse raised older suspicions, especially amongst the black community, that "federal programs were underwriting eugenicists who wanted to impose their views about population quality on minorities and poor women."[31]

Native American women were also victims of sterilization abuse up into the 1970s.[70] The organization WARN (Women of All Red Nations) publicized that Native American women were threatened that, if they had more children, they would be denied welfare benefits. The Indian Health Service also repeatedly refused to deliver Native American babies until their mothers, in labor, consented to sterilization. Many Native American women unknowingly gave consent, since directions were not given in their native language. According to the General Accounting Office, an estimate of 3,406 Indian women were sterilized.[70] The General Accounting Office stated that the Indian Health Service had not followed the necessary regulations, and that the "informed consent forms did not adhere to the standards set by the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW)."[71]

In 2013, it was reported that 148 female prisoners in two California prisons were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 in a supposedly voluntary program, but it was determined that the prisoners did not give consent to the procedures.[72] In September 2014, California enacted Bill SB1135 that bans sterilization in correctional facilities, unless the procedure is required to save an inmate's life.[73]

Euthanasia programs

Edwin Black wrote that one of the methods that was suggested to get rid of "defective germ-plasm in the human population" was euthanasia.[7] A 1911 Carnegie Institute report explored eighteen methods for removing defective genetic attributes, and method number eight was euthanasia.[7] The most commonly suggested method of euthanasia was to set up local gas chambers.[7] However, many in the eugenics movement did not believe that Americans were ready to implement a large-scale euthanasia program, so many doctors had to find clever ways of subtly implementing eugenic euthanasia in various medical institutions.[7] For example, a mental institution in Lincoln, Illinois fed its incoming patients milk infected with tuberculosis (reasoning that genetically fit individuals would be resistant), resulting in 30–40% annual death rates.[7] Other doctors practiced euthanasia through various forms of lethal neglect.[7]

In the 1930s, there was a wave of portrayals of eugenic "mercy killings" in American film, newspapers, and magazines. In 1931, the Illinois Homeopathic Medicine Association began lobbying for the right to euthanize "imbeciles" and other defectives.[74] The Euthanasia Society of America was founded in 1938.[75]

Overall, however, euthanasia was marginalized in the U.S., motivating people to turn to forced segregation and sterilization programs as a means for keeping the "unfit" from reproducing.[7]

Better baby contests

Mary deGormo, a former teacher, was the first person to combine ideas about health and intelligence standards with competitions at state fairs, in the form of baby contests. She developed the first such contest, the "Scientific Baby Contest" for the Louisiana State Fair in Shreveport, in 1908. She saw these contests as a contribution to the "social efficiency" movement, which was advocating for the standardization of all aspects of American life as a means of increasing efficiency.[21] DeGarmo was assisted by Doctor Jacob Bodenheimer, a pediatrician who helped her develop grading sheets for contestants, which combined physical measurements with standardized measurements of intelligence.[76]

The contest spread to other U.S. states in the early twentieth century. In Indiana, for example, Ada Estelle Schweitzer, a eugenics advocate and director of the Indiana State Board of Health's Division of Child and Infant Hygiene, organized and supervised the state's Better Baby contests at the Indiana State Fair from 1920 to 1932. It was among the fair's most popular events. During the contest's first year at the fair, a total of 78 babies were examined; in 1925 the total reached 885. Contestants peaked at 1,301 infants in 1930, and the following year the number of entrants was capped at 1,200. Although the specific impact of the contests was difficult to assess, statistics helped to support Schweitzer's claims that the contests helped reduce infant mortality.[77]

The intent of the contest was to educate the public about raising healthier children; however, its exclusionary practices reinforced social class and racial discrimination. In Indiana, for example, the contestants were limited to white infants; African American and immigrant children were barred from the competition for ribbons and cash prizes. In addition, the scoring was biased toward white, middle-class babies.[78][79] The contest procedure included recording each child's health history, as well as evaluations of each contestant's physical and mental health and overall development using medical professionals. Using a process similar to the one introduced at the Louisiana State Fair, and contest guidelines that the AMA and U.S. Children's Bureau recommended, scoring for each contestant began with 1,000 points. Deductions were made for defects, including a child's measurements below a designated average. The contestant with the most points (and the fewest defections) was declared the winner.[80][81][82]

Standardization through scientific judgment was a topic that was very serious in the eyes of the scientific community, but has often been downplayed as just a popular fad or trend. Nevertheless, a lot of time, effort, and money was put into these contests and their scientific backing, which would influence cultural ideas as well as local and state government practices.[83]

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People promoted eugenics by hosting "Better Baby" contests and the proceeds would go to its anti-lynching campaign.[13]

Fitter family for future

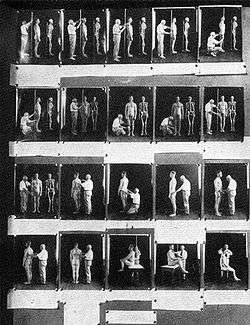

First appearing in 1920 at the Kansas Free Fair, Fitter Family competitions, continued all the way up to World War II. Mary T. Watts and Dr. Florence Brown Sherbon,[84][85] both initiators of the Better Baby Contests in Iowa, took the idea of positive eugenics for babies and combined it with a determinist concept of biology to come up with fitter family competitions.[86]

There were several different categories that families were judged in: Size of the family, overall attractiveness, and health of the family, all of which helped to determine the likelihood of having healthy children. These competitions were simply a continuation of the Better Baby contests that promoted certain physical and mental qualities.[87] At the time, it was believed that certain behavioral qualities were inherited from one's parents. This led to the addition of several judging categories including: generosity, self-sacrificing, and quality of familial bonds. Additionally, there were negative features that were judged: selfishness, jealousy, suspiciousness, high-temperedness, and cruelty. Feeblemindedness, alcoholism, and paralysis were few among other traits that were included as physical traits to be judged when looking at family lineage.[88]

Doctors and specialists from the community would offer their time to judge these competitions, which were originally sponsored by the Red Cross.[88] The winners of these competitions were given a Bronze Medal as well as champion cups called "Capper Medals." The cups were named after then Governor and Senator, Arthur Capper and he would present them to "Grade A individuals".[89]

The perks of entering into the contests were that the competitions provided a way for families to get a free health check up by a doctor as well as some of the pride and prestige that came from winning the competitions.[88]

By 1925 the Eugenics Records Office was distributing standardized forms for judging eugenically fit families, which were used in contests in several U.S. states.[90]

Planned Parenthood and the African American community

Concerns about eugenics arose in the African American community after the implementation of the Negro Project of 1939, which was proposed by Margaret Sanger who was the founder of Planned Parenthood.[91] In this plan, Sanger offered birth control to Black families in the United States to give them the chance to have a better life than what the group had been experiencing in the United States.[92] She also noted that the project was proposed to empower women. The Project often sought after prominent African American leaders to spread knowledge regarding birth control and the perceived positive effects it would have on the African American community, such as poverty and the lack of education.[93] Because of this, Sanger believed that African American ministers in the South would be useful to gain the trust of people within disadvantaged, African American communities as the Church was a pillar within the community.[93] Also, political leaders such as W.E.B. Dubois were quoted in the Project proposal criticizing Black people in the United States for having many children and for being less intelligent than their white counterparts:

... the mass of ignorant Negroes still breed carelessly and disastrously, so that the increase among Negroes, even more than the increase among Whites, is from that part of the population least intelligent and fit, and least able to rear their children properly.[92]

Even though The Negro Project received a lot of praise from white leaders and eugenicists of the time, it is important to note that Margaret Sanger wanted to clear concerns that this was not a project to terminate African Americans.[93] To add to the clarification, she received support from prominent African American leaders such as Mary McLeod Bethune and Adam Clayton Powell Jr.[92] These leaders and many more would later serve on the Negro National Advisory Council of Planned Parenthood Federation of America in 1942.

Still, many modern activists criticize Margaret Sanger for practicing eugenics on the African American community. Angela Davis, a leader who is associated with the Black Panther Party, made claims of Margaret Sanger targeting the African American community to reduce the population:

Calling for the recruitment of Black ministers to lead local birth control committees, the Federation's proposal suggested that Black people should be rendered as vulnerable as possible to their birth control propaganda.[94]

African American Support of Eugenics

Eugenics has been supported by members of the African American community for a long time. For example, Dr. Thomas Wyatt Turner, a professor at Howard University and a well respected scientist incorporated eugenics into his classes. The NAACP founder asked his students how eugenics can affect society in a good way in 1915. Eugenics seemed to be accepted by all kinds of people. W.E.B DuBois, a historian and civil rights leader had some beliefs that lined up with eugenics. He believed in developing the best versions of African Americans in order for his race to succeed. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. even received an award from planned parenthood in 1966 and in his acceptance speech, given by his wife, King discussed how large families are no longer functional in an urban setting. King claimed that in the cities, African Americans who continued to have children were over populating the ghettos. She continued by saying that having this many unwanted children is a bad problem that needs to be controlled, a belief that aligns with the eugenics movement.[95]

Influence on Nazi Germany

After the eugenics movement was well established in the United States, it spread to Germany. California eugenicists began producing literature promoting eugenics and sterilization and sending it overseas to German scientists and medical professionals.[7] By 1933, California had subjected more people to forceful sterilization than all other U.S. states combined. The forced sterilization program engineered by the Nazis was partly inspired by California's.[8]

The Rockefeller Foundation helped develop and fund various German eugenics programs,[96] including the one that Josef Mengele worked in before he went to Auschwitz.[7]

Upon returning from Germany in 1934, where more than 5,000 people per month were being forcibly sterilized, the California eugenics leader C. M. Goethe bragged to a colleague:

You will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind Hitler in this epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought ... I want you, my dear friend, to carry this thought with you for the rest of your life, that you have really jolted into action a great government of 60 million people.[7]

Eugenics researcher Harry H. Laughlin often bragged that his Model Eugenic Sterilization laws had been implemented in the 1935 Nuremberg racial hygiene laws.[97] In 1936, Laughlin was invited to an award ceremony at Heidelberg University in Germany (scheduled on the anniversary of Hitler's 1934 purge of Jews from the Heidelberg faculty), to receive an honorary doctorate for his work on the "science of racial cleansing". Due to financial limitations, Laughlin was unable to attend the ceremony and had to pick it up from the Rockefeller Institute. Afterwards, he proudly shared the award with his colleagues, remarking that he felt that it symbolized the "common understanding of German and American scientists of the nature of eugenics."[98]

Henry Friedlander wrote that although the German and American eugenics movements were similar, the US did not follow the same slippery slope as Nazi eugenics because American "federalism and political heterogeneity encouraged diversity even with a single movement." In contrast, the German eugenics movement was more centralized and had fewer diverse ideas.[99] Unlike the American movement, one publication and one society, the German Society for Racial Hygiene, represented all German eugenicists in the early 20th century.[99][100]

After 1945, however, historians began to try to portray the US eugenics movement as distinct and distant from Nazi eugenics.[101] Jon Entine wrote that eugenics simply means "good genes" and using it as synonym for genocide is an "all-too-common distortion of the social history of genetics policy in the United States." According to Entine, eugenics developed out of the Progressive Era and not "Hitler's twisted Final Solution."[102]

Compulsory sterilization prevention

The 1978 Federal Sterilization Regulations, created by the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare or HEW, (now the United States Department of Health and Human Services) outline a variety of prohibited sterilization practices that were often used previously to coerce or force women into sterilization.[103] These were intended to prevent such eugenics and neo-eugenics as resulted in the involuntary sterilization of large groups of poor and minority women. Such practices include: not conveying to patients that sterilization is permanent and irreversible, in their own language (including the option to end the process or procedure at any time without conceding any future medical attention or federal benefits, the ability to ask any and all questions about the procedure and its ramifications, the requirement that the consent seeker describes the procedure fully including any and all possible discomforts and/or side-effects and any and all benefits of sterilization); failing to provide alternative information about methods of contraception, family planning, or pregnancy termination that are nonpermanent and/or irreversible (this includes abortion); conditioning receiving welfare and/or Medicaid benefits by the individual or his/her children on the individuals "consenting" to permanent sterilization; tying elected abortion to compulsory sterilization (cannot receive a sought out abortion without "consenting" to sterilization); using hysterectomy as sterilization; and subjecting minors and the mentally incompetent to sterilization.[103][65][104] The regulations also include an extension of the informed consent waiting period from 72 hours to 30 days (with a maximum of 180 days between informed consent and the sterilization procedure).[65][103][104]

However, several studies have indicated that the forms are often dense and complex and beyond the literacy aptitude of the average American, and those seeking publicly funded sterilization are more likely to possess below-average literacy skills.[105] High levels of misinformation concerning sterilization still exist among individuals who have already undergone sterilization procedures, with permanence being one of the most common gray factors.[105][106] Additionally, federal enforcement of the requirements of the 1978 Federal Sterilization Regulation is inconsistent and some of the prohibited abuses continue to be pervasive, particularly in underfunded hospitals and lower income patient hospitals and care centers.[65][104]

See also

- Eugenics Board of North Carolina

- Eugenics in California

- Franz Boas

- International Federation of Eugenics Organizations

- Nazi human experimentation

- Poe v. Lynchburg Training School & Hospital (1981)

- Racial Integrity Act of 1924

- Racism in the United States

- Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942)

- Society for Biodemography and Social Biology

- Sterilization law in the United States

- Stump v. Sparkman (1978)

- The Kallikak Family

- Tuskegee syphilis experiment

- Unethical human experimentation in the United States

References

Notes

- ↑ "A social register of fitter families and better babies" The Milwaukee Sentinel . 26 May 1929.

- ↑ "Eugenics". Unified Medical Language System (Psychological Index Terms). National Library of Medicine. 26 September 2010.

- ↑ Galton, Francis (July 1904). "Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims". The American Journal of Sociology. X (1): 82, 1st paragraph. Bibcode:1904Natur..70...82.. doi:10.1038/070082a0. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

Eugenics is the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage.

- ↑ Susan Currell; Christina Cogdell (2006). Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in the 1930s. Ohio University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8214-1691-4.

- ↑ Lombardo, 2011: p. 1.

- ↑ Kühl, Stefan (14 February 2002). The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-19-534878-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Edwin Black (9 November 2003). "Eugenics and the Nazis – the California connection". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- 1 2 Timothy F. Murphy; Marc Lappé (1994). Justice and the Human Genome Project. University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-08363-9.

- ↑ [Kühl, Stefan (14 February 2002). The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-19-534878-1. ]

- ↑ Mukherjee, Siddhartha (2016). The Gene. Scribner. pp. 82–83.

- 1 2 3 Selden, 2005: p. 202.

- ↑ Ordover, 2003: p. xii.

- 1 2 3 Marilyn M. Singleton (Winter 2014). "The 'Science' of Eugenics: America's Moral Detour" (PDF). Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons. 19 (4). Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ↑ Dorr, Gregory; Logan, Angela (2011). "Quality, not mere quantity counts: black eugenics and the NAACP baby contests". In Lombardo, Paul. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Indiana University Press. pp. 68–92. ISBN 978-0253222695.

- ↑ Bender, 2009: p. 192.

- ↑ Kevles, 1986: pp. 133–135.

- ↑ Selden, 2005: p. 204.

- ↑ Hamilton Cravens, The Triumph of Evolution: American Scientists and the Heredity-Environment Controversy, 1900–1941 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978): 179.

- ↑ Stern, 2005: pp. 82–91.

- ↑ Elof Axel Carlson (2001). The Unfit: A history of a bad idea. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-87969-587-3.

- 1 2 Selden, 2005: p. 206.

- ↑ Cameron M. E. (1912). "Book Reviews". The American Journal of Nursing. 13 (1): 75–77. JSTOR 3404652.

- ↑ Ziegler, Mary (2008). "Eugenic Feminism: Mental Hygiene, The Women's Movement, And The Campaign For Eugenic Legal Reform, 1900–1935". Harvard Journal of Law & Gender. 31 (1): 211–236.

- 1 2 "The Sanger-Hitler Equation", Margaret Sanger Papers Project Newsletter, #32, Winter 2002/3. New York University Department of History

- ↑ Carole Ruth McCann. Birth Control Politics in the United States, 1916–1945. Cornell University Press. p. 100.

- ↑ Sanger, Margaret (1922). The Pivot of Civilization. Brentano's. pp. 100–101.

Nor do we believe that the community could or should send to the lethal chamber the defective progeny resulting from irresponsible and unintelligent breeding.

- ↑ Sanger, Margaret (1919). Birth Control and Racial Betterment (PDF). Birth Control Review. p. 11.

We maintain that a woman possessing an adequate knowledge of her reproductive functions is the best judge of time and conditions under which her child should be brought into the world. We maintain that it is her right, regardless of all other considerations, to determine whether she shall bear children or not, and how many children she shall bear if she chooses to become a mother.

- ↑ Sanger, Margaret (1920). Woman and the New Race. Brentano. p. 100.

- ↑ Larson, Edward J. (1995). Sex, Race, and Science: Eugenics in the Deep South. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 74.

- ↑ Larson, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kluchin, Rebecca M. (2009). Fit to Be Tied: Sterilization and Reproductive Rights in America 1950–1980. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 17–20.

- ↑ "1915 San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exposition: In color!". National Museum American History. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ "The Panama Pacific Exposition". Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ Stern, 2005: pp. 27–31.

- ↑ "Public Health". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association. XXVI (23): 1138. 6 June 1896. doi:10.1001/jama.1896.02430750040011.

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul A. (2010). Three generations, no imbeciles : eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell (Johns Hopkins pbk. ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801898242.

- ↑ The Indiana Supreme Court overturned the law in 1921 in Williams v. Smith, 131 NE 2 (Ind.), 1921, text at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ↑ On the legal history of eugenic sterilization in the U.S., see Paul Lombardo, "Eugenic Sterilization Laws", essay in the Eugenics Archive, available online at http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/essay8text.html.

- ↑ Stern, 2005: pp. 84, 144.

- 1 2 Severson, Kim (9 December 2011). "Thousands Sterilized, a State Weighs Restitution". New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Helms, Ann Doss and Tomlinson, Tommy (26 September 2011). "Wallace Kuralt's era of sterilization: Mecklenburg's impoverished had few, if any, rights in the 1950s and 1960s as he oversaw one of the most aggressive efforts to sterilize certain populations". Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ↑ McWhorter, 2009: p. 204.

- 1 2 McWhorter, 2009: p. 205.

- ↑ Watson, James D.; Berry, Andrew (2003). DNA: The Secret of Life. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-375-41546-7.

- 1 2 Lombardo, Paul; "Eugenics Laws Restricting Immigration,", Eugenics Archive

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul; "Eugenic Laws Against Race-Mixing", Eugenics Archive

- ↑ Committee On Immigration And Naturalization, United States. Congress. House (1921). Contagious Diseases Among Immigrants: Hearings Before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, House of Representatives, Sixty Sixth Congress, Third Session. 9 February 1921.

By setting up a eugenical standard for admission demanding a high natural excellence of all immigrants regardless of nationality and past opportunities, we can enhance and improve the national stamina and ability of future Americans. At present, not inferior nationalities but inferior individual family stocks are tending to deteriorate our national characteristics. Our failure to sort immigrants on the basis of natural worth is a very serious national menace.

- ↑ Statement of Mr. Harry H. Laughlin, Secretary of the Eugenics Research Association, Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, N. Y.; Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, House of Representatives, Washington D.C., 16 April 1920.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen J. (1981) The mismeasure of man. Norton:

- ↑ Dorr, Gregory (2008). Segregation's Science. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 10.

- ↑ Kline, Wendy (2005). Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics From the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom. University of California Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Critchlow, Donald T. (1999). Intended Consequences: Birth Control, Abortion, and the Federal Government in Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Lombardo, 2011: p. ix.

- ↑ Indiana Supreme Court Legal History Lecture Series, "Three Generations of Imbeciles are Enough:"Reflections on 100 Years of Eugenics in Indiana, at In.gov Archived 13 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Williams v. Smith, 131 NE 2 (Ind.), 1921, text at Archived 1 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Larson 2004, pp. 194–195 Citing Buck v. Bell 274 U.S. 200, 205 (1927)

- ↑ Dorr, Gregory Michael. "Encyclopedia Virginia: Buck v Bell". Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul; "Eugenic Sterilization Laws", Eugenics Archive

- ↑ J. Mitchell Miller (6 August 2009). 21st Century Criminology: A Reference Handbook, Volume 1. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-4129-6019-9.

- ↑ Tukufu Zuberi (2001). Thicker than blood: how racial statistics lie. University of Minnesota Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8166-3909-0.

- ↑ Ladelle McWhorter (2009). Racism and Sexual Oppression in Anglo-America: A Genealogy. Indiana University Press. p. 377. ISBN 0-253-22063-7.

- ↑ Oklahoma City January 2 "sterilization of habitual criminals". The Montreal Gazette. January 3, 1934

- ↑ Gordon, Linda (2003). The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 345. ISBN 0-252-07459-9.

- ↑ "Relf v. Weinberger: Sterilization Abuse". The Southern Poverty Law Center.

- 1 2 3 4 Bowman, Cynthia Grant; Rosenbury, Laura A.; Tuerkheimer, Deborah; Yuracko, Kimberly A. (2010). Feminist Jurisprudence Cases and Material. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company. pp. 413–419. ISBN 978-0314264633.

- ↑ Stern, Alexandra Minna (2005). "Sterilized in the Name of Public Health: Race, Immigration, and Reproductive Control in Modern California". American Journal of Public Health. 95 (7): 1128–1138. doi:10.2105/ajph.2004.041608. PMC 1449330.

- ↑ Begos, Kevin (2011-05-18). "The American eugenics movement after World War II (part 1 of 3)". INDY Week. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Begos, Kevin (2011-05-18). "The American eugenics movement after World War II (part 1 of 3)". INDY Week. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- 1 2 3 Ward, Martha C. (1986). Poor Women, Powerful Men: America's Great Experiment in Family Planning. Boulder: Westview Press. p. 95.

- 1 2 Lawrence, Jane (2000). "he Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American Women". The American Indian Quarterly. 3. 24 (3): 400–419. doi:10.1353/aiq.2000.0008.

- ↑ Bruce E. Johansen (September 1998). "Sterilization of Native American Women". Native Americas.

- ↑ "Sterilization Abuse in State Prisons" News 07/23/2013 author Alex Stern

- ↑ "SB 1135". CA Gov. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Pernick, Martin (1999). The Black Stork: Eugenics and the Death of "Defective" Babies in American Medicine and Motion Pictures since 1915. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0195135398.

- ↑ Pernick, 2009: p. 161.

- ↑ Selden 2005: p. 207.

- ↑ The contests occurred at time when health indicators for Indiana's babies improved. For example, the percentage underweight babies in the state dropped from 10 percent in 1920 to 2 percent in 1929. See: Stern, Alexandra Minna (2002). "Making Better Babies: Public Health and Race Betterment in Indiana, 1920–1935". American Journal of Public Health. 92 (5): 742–752. PMC 3222231. Also: Stern, Alexandra Minna (March 2007). "'We Cannot Make a Silk Purse Out of a Sow's Ear': Eugenics in the Hoosier Heartland". Indiana Magazine of History. Bloomington: Indiana University. 103 (1): 26–27. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ↑ Stern, "Making Better Babies, " pp. 742, 746–50.

- ↑ Gugin, Linda C., and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 300–01. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

- ↑ Gugin and St. Clair, eds., "Indiana's 200," pp. 299–300.

- ↑ Stern, "'We Cannot Make a Silk Purse Out of a Sow's Ear,'" pp. 24 and 27

- ↑ Crnic, Meghan (2009), "Better babies: Social engineering for 'a better nation, a better world'", Endeavour, 33 (1): 12–17, doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2008.11.001, PMID 19217162

- ↑ Pernick, 2002

- ↑ "A social register of fitter families and better babies" The Milwaukee Sentinel . 26 May 1929

- ↑ "Fitter family contests" eugenics archive.ca

- ↑ "Fitter Family Contests." Eugenics Archive. Web. 2 March 2010. .

- ↑ Boudreau 2005:

- 1 2 3 Selden, 2005:

- ↑ Selden, 2005: p. 211.

- ↑ D. E. Bender (2011). Rt-American Abyss Z. Cornell University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8014-5713-5.

- ↑ The Margaret Sanger Papers Project (Fall 2001). "Birth Control or Race Control? Sanger and the Negro Project". New York University.

- 1 2 3 Peter C. Engelman, ed. (2001). ""Birth Control or Race Control? Margaret Sanger and the Negro Project"". New York University.

- 1 2 3 "Opposition Claims About Margaret Sanger" (PDF). Planned Parenthood. Katherine Dexter McCormick Library. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ "You Know Which Right Winger Accused Planned Parenthood of Racism?". Frontpage Mag. 22 August 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ↑ Begos, Kevin (2011-05-18). "The American eugenics movement after World War II (part 1 of 3)". INDY Week. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Kühl, Stefan (10 February 1994). The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-19-508260-5. Lay summary (18 January 2015).

The Foundation continued to support German eugenicists even after the National Socialists had gained control of German science.

- ↑ Jackson, John P.; Weidman, Nadine M. (2005). Race, Racism, and Science: Social Impact and Interaction. Rutgers University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8135-3736-8.

- ↑ Lombardo, 2008: pp. 211–213.

- 1 2 Friedlander, Henry (2000). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0807846759.

Although the German eugenics movement, led until the Weimar years by Alfred Ploetz and Wilhelm Schallmayer, did not differ radically from the American movement, it was more centralized. Unlike in the United States, where federalism and political heterogeneity encouraged diversity even with a single movement, in Germany one society, the German Society for Race Hygiene (Deutsche Gesellschaft fue Rassenhygiene), eventually represented all eugenicists, while one journal, the Archiv fur Rassen- und Gsellschafts Biologie, founded by Ploetz in 1904, remained the primary scientific publication of German Eugenics.

- ↑ Rubenfeld, Sheldon; Benedict, Susan (2014). Human Subjects Research after the Holocaust. Springer. p. 13. ISBN 978-3319057019.

Considering America's strong interest in eugenics, it is reasonable to ask why America did not slide down the same slippery slope as Germany.

- ↑ Kühl 2001: p. xiv.

- ↑ Let's (Cautiously) Celebrate the "New Eugenics", Huffington Post, (30 October 2014).

- 1 2 3 US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. 42 Code of Federal Regulations. 441.250–259 (1978).

- 1 2 3 Petchesky, Rosalind Pollack (1990). Abortion and Woman's Choice: The State, Sexuality, and Reproductive Freedom (revised edition). Lebanon, NH: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1555530754.

- 1 2 Borrero, Sonya; Zite, Nikki; Creinin, Mitchell D. (2012). "Federally Funded Sterilization: Time to Rethink Policy?". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (10): 1822–1825. doi:10.2105/ajph.2012.300850. PMC 3490665.

- ↑ Borrero; et al. (2011). "Racial Variation in Tubal Sterilization Rates: Role of Patient-Level Factors". Fertil Steril. 95 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.031. PMC 2970690. PMID 20579640.

Bibliography

- Bender, Daniel E. (2009). American abyss: savagery and civilization in the age of industry. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4598-9.

- Black, Edwin (9 November 2003). "Eugenics and the Nazis – the California connection". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Boudreau, Erica Bicchieri (2005). "'Yea, I have a Goodly Heritage': Health Versus Heredity in the Fitter Family Contests, 1920–1928". Journal of Family History. 30 (4): 366–87. doi:10.1177/0363199005276359. PMID 16304739.

- Engs, Ruth C. (2005). The eugenics movement: an encyclopedia. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32791-9.

- Kevles, Daniel J. (1986). In the Name of Eugenics: genetics and the uses of human heredity. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05763-0.

- Kühl, Stefan (2001). The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-514978-4.

- Lombardo, Paul A. (2008). Three generations, no imbeciles: eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9010-9.

- Lombardo, Paul A. (2011). A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22269-5.

- McWhorter, Ladelle (2009). Racism and sexual oppression in Anglo-America: a genealogy. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22063-9.

- Murphy, Timothy F. & Lappé, Marc, eds. (1994). Justice and the human genome project. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08363-9.

- Ordover, Nancy (2003). American eugenics: race, queer anatomy, and the science of nationalism. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3559-7.

- Pernick, Martin S. (1999). The Black Stork: Eugenics and the Death of "Defective" Babies in American Medicine and Motion Pictures Since 1915. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513539-8.

- Pernick, Martin S. (2002). "Taking Better Baby Contests Seriously". American Journal of Public Health. 92 (5): 707–708. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.5.707. PMC 1447148. PMID 11988430.

- Selden, Steven (2005). "Transforming Better Babies into Fitter Families: Archival Resources and the History of the American Eugenics Movement, 1908–1930". American Philosophical Society. 149 (2): 199–225.

- Stern, Alexandra (2005). Eugenic nation: faults and frontiers of better breeding in modern America. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24444-3.

Further reading

- Allen, Garland E. (1987). "The role of experts in scientific controversy". In Engelhardt, Hugo Tristram & Caplan, Arthur L. Scientific controversies: case studies in the resolution and closure of disputes in science and technology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–202. ISBN 978-0-521-27560-6.

- Barkan, Elazar (1993). The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States Between the World Wars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45875-7.

- Bashford, Alison & Levine, Philippa, eds. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537314-1.

- Bauman, Zygmunt (2000). Modernity and the Holocaust. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8719-4.

- Black, Edwin (2004). War against the weak: eugenics and America's campaign to create a master race. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56858-321-1.

- Cuddy, Lois A. & Roche, Claire M., eds. (2003). Evolution and eugenics in American literature and culture, 1880–1940: essays on ideological conflict and complicity. Bucknell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8387-5555-6.

- Currell, Susan (2006). Popular eugenics: national efficiency and American mass culture in the 1930s. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1692-1.

- Dowbiggin, Ian Robert (1997). Keeping America sane: psychiatry and eugenics in the United States and Canada, 1880–1940. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8398-1.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1996). The Mismeasure of Man (2nd, revised ed.). W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31425-0.

- Haller, Mark H. (1963). Eugenics: Hereditarian Attitudes in American Thought. Rutgers University Press.

- Hansen, Randall and King, Desmond (eds.), Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race, and the Population Scare in Twentieth-Century North America. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hasian, Marouf Arif (1996). The rhetoric of eugenics in Anglo-American thought. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-1771-7.

- Kline, Wendy (2005). Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24674-4.

- Kohn, Marek (1995). The Race Gallery: The Return of Racial Science. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Larson, Edward J. (1996). Sex, Race, and Science: Eugenics in the Deep South. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5511-5.

- Lusane, Clarence (2002). Hitler's black victims: the historical experiences of Afro-Germans, European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi era. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-93295-0.

- Maxwell, Anne (2010). Picture Imperfect: Photography and Eugenics, 1870–1940. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-415-4.

- McCann, Carole Ruth (1999). Birth control politics in the United States, 1916–1945. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8612-8.

- Mendelsohn, Everett (March–April 2000). "The Eugenic Temptation: When ethics lag behind technology". Harvard Magazine.

- Rafter, Nicole Hahn (1988). White Trash: The Eugenic Family Studies, 1877–1919. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-030-3.

- Reilly, Philip R. (1991). The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4096-8.

- Rosen, Christine (2004). Preaching eugenics: religious leaders and the American eugenics movement. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515679-9.

- Ross, Loretta (2000). "Eugenics: African-American Case Study—Eugenics and Family Planning". Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Education: Health to Hypertension. Vol. 2. Psychology Press. p. 638. ISBN 978-0-415-92089-6.

- Schoen, Johanna (2005). Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807855850.

- Solinger, Rickie (2005). Pregnancy and Power: A Short History of Reproductive Politics in America. New York, NY: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0814798287.

- Smith, J. David. (1993). The Eugenic Assault on America: Scenes in Red, White and Black. George Mason University Press. ISBN 978-0-913969-53-3.

- Spiro, Jonathan P. (2009). Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. University of Vermont Press. ISBN 978-1-58465-715-6.

- Tucker, William H. (2007). The funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07463-9. Lay summary.

External links

- The Color of Democracy: A Japanese Public Health Official's Reconnaissance Trip to the U.S. South Takeuchi-Demirci, Aiko. Southern Spaces 18 March 2011.

- "Eugenics", Scope Note 28, Bioethics Research Center, Georgetown University

- Plotz, David. "The Better Baby Business", Washington Post, 13 March 2001. Web. 25 April 2010. .

- Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States, Kaelber, Lutz (ed.)

- Eugenics in the United States and Britain, 1890–1930: a comparative analysis

- Eugenics in the United States

- "Buck v. Bell (1927)" by N. Antonios and C. Raup at the Embryo Project Encyclopedia