Syriac Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Eastern liturgical rites |

|

Syriac Christianity (Syriac: ܡܫܝܚܝܘܬܐ ܣܘܪܝܝܬܐ / Mšiḥāyuṯā Suryāyṯā) refers to Eastern Christian traditions that employ Syriac in their liturgy. Syriac is a variety of Middle Aramaic that emerged in Edessa, Upper Mesopotamia, in the early first century AD, and is considered to be closely related to the Jewish Palestinian Aramaic spoken by Jesus.[1] Tracing back their historical heritage to the 1st century, Syriac Christianity is today represented in the Middle East by the Maronite Church, Syriac Catholic Church, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, and the Ancient Church of the East, as well as by the Saint Thomas Christians of respective communions centered in Kerala, India, as well as independent communities, such as the Chaldean Church of the East in Brazil.

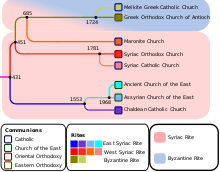

Christianity began in the Middle East in Jerusalem among Aramaic-speaking Jews. It quickly spread to other Aramaic-speaking Semitic peoples, in Parthian Empire-ruled Asōristān (modern Iraq), Roman Syria. Syriac Christianity is divided into two major liturgical traditions: the East Syriac Rite, historically centered in Upper Mesopotamia and the West Syriac Rite, centered in Antioch in the Levant by the Mediterranean coast.

The East Syriac Rite tradition was historically associated with the Church of the East, and it is currently employed by the Middle Eastern churches that descend from it: the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, and the Chaldean Catholic Church (the members of such churches are Eastern Aramaic-speaking ethnic Assyrians), as well as by the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church of India, and the Chaldean Syrian Church of India which is an archbishopric of the Assyrian Church of the East.

The West Syriac Rite tradition is used by the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, the Maronite Church as well as by the Malankara Church of India, which follow the Malankara Rite tradition of the Saint Thomas Christian community. Adherents sometimes identify as "Syriacs" or "Assyrians".

History

Syriac Christian heritage is transmitted through various Neo Aramaic dialects (particularly the Syriac dialect of Assyria and Upper Mesopotamia) of old Aramaic. Unlike the Greek Christian culture, Assyrian Christian culture borrowed much from early Rabbinic Judaism and its own indigenous ancient Mesopotamian culture. Whereas Latin and Greek Christian cultures became protected by the Roman and Byzantine empires respectively, Syriac Christianity often found itself marginalised and sometimes actively persecuted by the Zoroastrian rulers of the Parthian Empire and succeeding Sassanid Empire. Antioch was the political capital of this culture, and was the seat of the Patriarchs of the church. However, Antioch was heavily Hellenized, and the Assyrian cities of Edessa, Nisibis and Sassanid Ctesiphon became Syriac cultural centres.

The early literature of Syriac Christianity includes the Diatessaron of Tatian; the Curetonian Gospels and the Syriac Sinaiticus; the Peshitta Bible; the Doctrine of Addai and the writings of Aphrahat; and the hymns of Ephrem the Syrian.

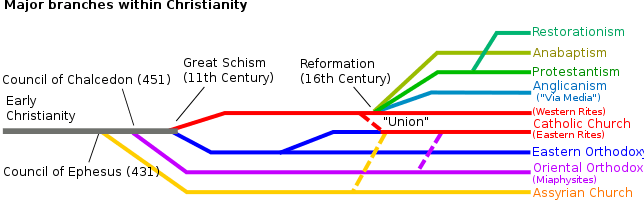

The first division between Syriac Christians and Western Christianity occurred in the 5th century, following the First Council of Ephesus in 431, when the Assyrian Christians of the Sassanid Persian Empire were separated from those in the west over the Nestorian Schism. This split owed just as much to the politics of the day as it did to theological orthodoxy. Ctesiphon, which was at the time also the Sassanid capital, eventually became the capital of the Church of the East.

After the Council of Chalcedon in 451, many Syriac Christians within the Roman Empire rebelled against its decisions. The Patriarchate of Antioch was then divided between a Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian communion. The Chalcedonians were often labelled 'Melkites' (Emperor's Party), while their opponents were labelled as Monophysites (those who believe in the one rather than two natures of Christ) and Jacobites (after Jacob Baradaeus). The Maronite Church found itself caught between the two (allegedly embracing Monothelitism), but claims to have always remained faithful to the Catholic Church and in communion with the bishop of Rome, the Pope.[2]

The church has persisted as a separate entity under Islamic rule. The community was one of those granted autonomy in governing itself in religious and family matters under the millet system.[3] In the 19th century many left for other parts of Christendom, creating a substantial diaspora.[4]

Over time, some groups within each of these branches have entered into communion with the Church of Rome, becoming Eastern Catholic Churches.

Names

Indigenous Aramaic speakers of Mesopotamia (Syriac: ܣܘܪܝܝܐ, Arabic: سُريان)[5] adopted Christianity very early, and from the first century onwards, it began to supplant the three-millennia-old traditional ancient Mesopotamian religion, although this religion did not fully die out until as late as the tenth century. The kingdom of Osroene was the first Christian kingdom in history.

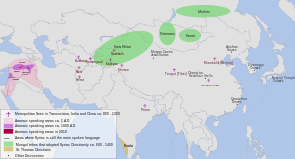

In 431 the Council of Ephesus declared Nestorianism to be a heresy. Nestorian priests, who were persecuted in the Byzantine Empire, sought refuge in Mesopotamia, then part of the Sasanian Empire. There was a synthesis between Syriac-speaking churches and Nestorian doctrine, which spread Christianity to Persia, India, China, and Mongolia. This was the beginning of the Church of the East, the eastern branch of Syriac Christianity. The western branch, the Jacobite Church, appeared after the Council of Chalcedon condemned Monophysitism in 451.[6]

Churches of the Syriac tradition

- West Syriac Rite

- The Syriac Orthodox Church (Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Church of Antioch and all the East)

- The Jacobite Syrian Christian Church; (Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Church of India within the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate)

- The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Autocephalous; Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Church of India) with her part the Brahmavar (Goan) Orthodox Church

- The West Syriac Rite Churches under the Catholic Church

- The Syriac Catholic Church, a West Syriac Rite Eastern Catholic church.

- The Maronite Church, a West Syriac Rite Eastern Catholic Church.

- The Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, a West Syriac Rite Eastern Catholic Church based in Kerala, India.

- The Malankara Marthoma Syrian Church. (Mar Thoma Church), an Eastern Oriental church based in Kerala, India. Mar Thoma church is in communion with the Anglican Church.

- The Malabar Independent Syrian Church (Thozhiyur church), an independent church based in Kerala, India.

- The Syriac Orthodox Church (Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Church of Antioch and all the East)

- East Syriac Rite

- Church of the East, founded in Assyria, became known as the Nestorian Church, once widely spread through Asia

- The Assyrian Church of the East, the direct continuation of the Church of the East

- The Chaldean Syrian Church an archbishopric the Assyrian Church India based

- The Ancient Church of the East, split from the Assyrian Church of the East in the 1960s

- The Assyrian Church of the East, the direct continuation of the Church of the East

- The East Syriac Rite Churches under the Catholic Church

- The Chaldean Catholic Church (originally called The Church of Assyria and Mosul), an East Syriac Rite Eastern Catholic Church, only emerged from the Church of the East following the split with the Assyrian Church of the East in the 1683 AD.

- The Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, an East Syriac Rite Eastern Catholic Church based in Kerala, India

- Church of the East, founded in Assyria, became known as the Nestorian Church, once widely spread through Asia

Syriac Christians were involved in the mission to India, and many of the ancient churches of India are in communion with their Syriac cousins. These Indian Christians are known as Saint Thomas Christians.

In modern times, various Evangelical denominations began to send representatives among the Syriac peoples. As a result, several Evangelical groups, particularly the "Assyrian Pentecostal Church" (most in America, Iran, and Iraq) have been established and the Aramean Free Church (most in Germany, Sweden, Amerika and Syria). However, despite these Assyrian protestants having been converted from the Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church, due to their recent historical origin, such groups and others are not normally classified among those Eastern Churches to which the term "Syriac Christianity" is traditionally applied.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Allen C. Myers, ed (1987). "Aramaic". The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. p. 72. ISBN 0-8028-2402-1. "It is generally agreed that Aramaic was the common language of Palestine in the first century A.D. Jesus and his disciples spoke the Galilean dialect, which was distinguished from that of Jerusalem (Matt. 26:73)."

- ↑ Moosa, Matti. The Maronites in history. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1986

- ↑ Ye'Or, Bat. The decline of eastern Christianity under Islam: from jihad to dhimmitude. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, US, 1996

- ↑ Chaillot, Christine. "The Syrian Orthodox Church Of Antioch And All The East. Geneva: Inter-Orthodox Dialogue 1998

- ↑ Donabed, Sargon (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7486-8605-6.

- ↑ T.V. Philip, East of the Euphrates: Early Christianity in Asia

Sources

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). bThe Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). Syriac Studies: A Classified Bibliography, 1960-1990. Kaslik: Parole de l'Orient.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1997). A Brief Outline of Syriac Literature. Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1902). Synodicon orientale ou recueil de synodes nestoriens (PDF). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in historyb. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N. (2010). "Nestorius of Constantinople: Condemnation, Suppression, Veneration: With special reference to the role of his name in East-Syriac Christianity". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 62 (3–4): 165–190.

External links

- Jacobite Syrian Church

- (in French) – Translation into English Syriac Christianity on WikiSyr

- (in French) – Translation into English Syriac Catholic Circle

- Qambel Maran- Syriac chants from South India- a review and liturgical music tradition of Syriac Christians revisited

- Traditions and rituals among the Syrian Christians of Kerala

- Audio Aramaic-Bible

- The Center for the Study of Christianity: A Comprehensive Bibliography on Syriac Christianity