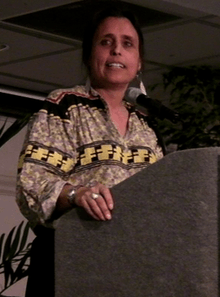

Winona LaDuke

| Winona LaDuke | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

August 18, 1959 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Education |

Harvard University (BA) Antioch University (MA) |

| Political party | Green |

| Children | 3 |

Winona LaDuke (born August 18, 1959) is an American environmentalist, economist, and writer, known for her work on tribal land claims and preservation, as well as sustainable development. In 1996 and 2000, she ran for Vice President as the nominee of the Green Party of the United States, on a ticket headed by Ralph Nader.

She is the executive director of Honor the Earth, a Native environmental advocacy organization that plays an active role in the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.[1]

Early life and education

Winona (meaning "first daughter" in Dakota language) LaDuke was born in 1959 in Los Angeles, California, to Betty Bernstein and Vincent LaDuke (later known as Sun Bear[2]). Her father was from the Ojibwe White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, and her mother of Jewish European ancestry from the Bronx, New York. Though LaDuke spent some of her childhood in Los Angeles, she was primarily raised in Ashland, Oregon.[3] Due to her father's heritage, she was enrolled with the Ojibwe Nation at an early age, but she did not live at White Earth, or on any other reservation, until 1982. She started work at White Earth after she graduated college, when she got a job there as principal of the high school.[2]

After her parents married, Vincent LaDuke worked as an actor in Hollywood, with supporting roles in Western movies, while Betty LaDuke completed her academic studies. The couple separated when Winona was five, and her mother took a position as an art instructor at Southern Oregon College, now Southern Oregon University at Ashland, which was then a small logging and college town near the California border.[2] In the 1980s, LaDuke's father Vincent reinvented himself as a New Age spiritual leader and went by the name Sun Bear.[2]

While growing up in Ashland, LaDuke attended public school and was on the debate team in high school. She attended Harvard University, where she became part of a larger group of Indian activists, and graduated in 1982 with a Bachelor of Arts in Economics (rural economic development).[2] When LaDuke moved to White Earth she did not know the Ojibwe language, or many people, and was not quickly accepted. While working as the principal of the local Minnesota reservation high school she completed research for her master's thesis on the reservation's subsistence economy and became involved in local issues. She completed an M.A. in Community Economic Development through the distance-learning program of Antioch University.[2]

Career and activism

_(cropped).jpg)

While working as a principal at the high school, LaDuke became an activist. In 1985 she helped found the Indigenous Women's Network. She worked with Women of All Red Nations to publicize American forced sterilization of Native American women.

Next she became involved in the struggle to recover lands for the Anishinaabe. An 1867 treaty with the United States had originally provided a territory of more than 860,000 acres for the White Earth Indian Reservation. Under the Nelson Act of 1889, an attempt to have the Anishinaabe assimilate by adopting a European-American model of subsistence farming, communal tribal land had been allotted to individual households. The US classified any land in excess as surplus, allowing it to be sold to non-natives. In addition, many Anishinaabe sold their land individually over the years; these elements resulted in the tribe's losing control of most of its land. By the mid-20th century, the tribe held only one-tenth of the land within its reservation.[2]

In 1989, LaDuke founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project (WELRP) in Minnesota with the proceeds of a human rights award from Reebok. The goal is to buy back land within the reservation that had been bought by non-Natives and to create enterprises that provide work to Anishinaabe. By 2000, the foundation had bought 1200 acres, which it held in a conservation trust for eventual cession to the tribe.[2]

The non-profit is also working to reforest the lands and a revive cultivation of wild rice, long a traditional food. It markets that and other traditional products, including hominy, jam, buffalo sausage and other products. It has started an Ojibwe language program, a herd of buffalo, and a wind-energy project.[2]

LaDuke is also Executive Director of Honor the Earth, an organization she co-founded with the non-Native folk-rock duo, the Indigo Girls in 1993. The organization's mission is:

to create awareness and support for Native environmental issues and to develop needed financial and political resources for the survival of sustainable Native communities. Honor the Earth develops these resources by using music, the arts, the media, and Indigenous wisdom to ask people to recognize our joint dependency on the Earth and be a voice for those not heard.[4]

LaDuke was selected by The Evergreen State College Class of 2014 to be a keynote speaker and delivered her address at the school's graduation on June 13, 2014.

In 2016, LaDuke was involved in the Dakota Access Pipeline protests, participating at the resistance camps in North Dakota as well as speaking to the media on the issue.[5]

Political career

In 1996 and 2000, LaDuke ran as the vice-presidential candidate with Ralph Nader on the Green Party ticket. She was not endorsed by any tribal council or other tribal government. LaDuke endorsed the Democratic Party ticket for the president and vice-president in 2004,[6] 2008,[7] and 2012.[8]

In 2016, Robert Satiacum, Jr., a faithless elector from Washington cast his presidential vote for Native American activist, Faith Spotted Eagle; he then cast his vote for Vice President for Winona LaDuke, making her the first Native American woman to receive an Electoral College vote for Vice President.[9]

White Earth Land Recovery Project

WELRP has worked to revive cultivation and harvesting of wild rice, a traditional food of the Ojibwe people. It produces and sells traditional foods and crafts through its label, Native Harvest.[10]

Honor the Earth

Honor the Earth is a national advocacy group encouraging public support and funding for Native environmental groups. With Honor the Earth, Winona works nationally and internationally on issues of climate change, renewable energy, sustainable development, food systems and environmental justice. Members of Honor the Earth are active in the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.[1]

Books, films, and media

LaDuke has authored many books:

- Last Standing Woman (1997), novel.

- All our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life (1999), about the drive to reclaim tribal land for ownership

- Recovering the Sacred: the Power of Naming and Claiming (2005), a book about traditional beliefs and practices.

- The Militarization of Indian Country (2013)

- The Sugar Bush (1999)

- The Winona LaDuke Reader: A Collection of Essential Writings (2002)

- All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life (2016)

She has also co-written several other books including:

- Conquest: Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide

- Grassroots: A Field Guide for Feminist Activism

- Sister Nations: Native American Women Writers on Community

- Struggle for the Land: Native North American Resistance to Genocide, Ecocide, and Colonization

- Cutting Corporate Welfare

- Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions

- New Perspectives on Environmental Justice: Gender, Sexuality, and Activism

- Make a Beautiful Way: The Wisdom of Native American Women

- How to Say I Love You in Indian

- Earth Meets Spirit: A Photographic Journey Through the Sacred Landscape

- Otter Tail Review: Stories, Essays and Poems from Minnesota's Heartland

- Daughters of Mother Earth: The Wisdom of Native American Women

LaDuke's editorials and essays have been published in national and international media.

Television and film appearances:

- Appearance in the documentary film Anthem, directed by Shainee Gabel and Kristin Hahn.[11]

- Appearance in the TV documentary The Main Stream.[12]

- Appearance on The Colbert Report on June 12, 2008.[13]

- Featured in 2017 full-length documentary First Daughter and the Black Snake, directed by Keri Pickett. Chronicles LaDuke’s opposition against the Canadian-owned Enbridge plans to route a pipeline through land granted to her tribe in an 1855 Treaty.[14]

Legacy and honors

- 1994, LaDuke was nominated by Time magazine as one of America's fifty most promising leaders under forty years of age.

- 1996, she was given the Thomas Merton Award

- 1997, she was granted the BIHA Community Service Award

- 1998, she won the Reebok Human Rights Award.

- 1998, Ms. Magazine named her Woman of the Year for her work with Honor the Earth.

- Ann Bancroft Award for Women's Leadership Fellowship.

- 2007, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[15]

- 2015, she received an honorary doctorate degree from Augsburg College.[16]

- 2017, she received the Alice and Clifford Spendlove Prize in Social Justice, Diplomacy and Tolerance, at the University of California, Merced.[17]

Marriage and family

LaDuke married Randy Kapashesit, a Cree leader, when working in opposition to a major hydroelectric project near Moose Factory, Ontario. They had two children together: a daughter Waseyabin (born 1988) and a son Ajuawak (born 1991). They divorced after several years.[2]

LaDuke's current partner is Kevin Gasco. They had a child in 1999. She has also cared for a niece and nephew for an extended period. She and Gasco share her grandchildren.[2]

On November 9, 2008, LaDuke's house in Ponsford, Minnesota, burned down while she was in Boston. No one was injured, but all of LaDuke's personal property burned, including her extensive library and indigenous art and artifact collection.[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 Winona LaDuke (August 25, 2016). "What Would Sitting Bull Do?". Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Peter Ritter, "The Party Crasher", Minneapolis News, October 11, 2000

- ↑ Willamette Week | "Winona Laduke" | July 19th, 2006 Archived August 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "About Us". Honor The Earth. Retrieved 2017-04-15.

- ↑ Amy Goodman (September 4, 2016). "VIDEO: Dakota Access Pipeline Company Attacks Native American Protesters with Dogs and Pepper Spray". democracynow.org. Democracy Now!. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Winona LaDuke endorsement of John Kerry for president". October 20, 2004. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ↑ "LaDuke and the lessons she learned with Nader". Minnesota Post. May 22, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Winona LaDuke on Presidential Politics (7:41)". Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ↑ "How Faith Spotted Eagle became the first Native American to win an electoral vote for president". LA Times. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- ↑ "Ricing Time: Harvesting on the Lakes of White Earth", National Public Radio. 12 Nov. 2004.

- ↑ Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics (2017). "Winona LaDuke". Iowa State University Archives of Women's Political Communication. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ globalreach.com, Global Reach Internet Productions, LLC - Ames, IA -. "Winona LaDuke - Women's Political Communication Archives". www.womenspeecharchive.org. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ LaDuke on The Colbert Report, colbertnation.com.

- ↑ ""Urgent Cinema: Winona LaDuke and the Enbridge Pipeline"". Walker Art Center. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ↑ LaDuke, Winona - National Women’s Hall of Fame

- ↑ "Day Undergraduate Ceremony - Commencement". Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Indigenous Activist Winona LaDuke Wins Spendlove Prize - UC Merced". www.ucmerced.edu. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Winona LaDuke to rebuild home destroyed by fire". News from Indian Country. November 17, 2008. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

Further reading

- Andrews, Max (Ed.), Land, Art: A Cultural Ecology Handbook. London, Royal Society of Arts, 2006, ISBN 978-0-901469-57-1. Interview with Winona LaDuke

External links

- Winona LaDuke - Discover the Networks

- Honor the Earth, Official Website

- Winona LaDuke at nativeharvest.com

- Winona LaDuke, Voices from the Gap, University of Minnesota

- VP Acceptance Speech, 1996 Green Party Convention

- "Nader's No. 2" at Salon.com (July 13, 2000)

- Winona LaDuke interview with Majora Carter of The Promised Land radio show (2000)

- Winona LaDuke on IMDb

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| First | Green nominee for Vice President of the United States 1996, 2000 |

Succeeded by Pat LaMarche |