Long March (rocket family)

A Long March rocket (simplified Chinese: 长征系列运载火箭; traditional Chinese: 長征系列運載火箭; pinyin: Chángzhēng xìliè yùnzài huǒjiàn) or Changzheng rocket in Chinese pinyin is any rocket in a family of expendable launch systems operated by the People's Republic of China. Development and design falls under the auspices of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology. In English, the rockets are abbreviated as LM- for export and CZ- within China, as "Chang Zheng" means "Long March" in Chinese pinyin. The rockets are named after the Long March of Chinese communist history.

History

China used the Long March 1 rocket to launch its first satellite, Dong Fang Hong 1 (lit. "The East is Red 1"), into Low Earth orbit on April 24, 1970, becoming the fifth nation to achieve independent launch capability. Early launches had an inconsistent record, focusing on the launching of Chinese satellites. The Long March 1 was quickly replaced by the Long March 2 family of launchers.

Entry into commercial launch market

After the U.S. Space Shuttle Challenger was destroyed in 1986, a growing commercial backlog gave China the chance to enter the international launch market. In September 1988, U.S. President Ronald Reagan agreed to allow U.S satellites to be launched on Chinese rockets.[1] AsiaSat 1, which had originally been launched by the Space Shuttle and retrieved by another Space Shuttle after a failure, was launched by the Long March 3 in 1990 as the first foreign payload on a Chinese rocket.

However, major setbacks occurred in 1992–1996. The Long March 2E was designed with a defective payload fairing, which collapsed when faced with the rocket's excessive vibration. After just seven launches, the Long March 2E destroyed the Optus B2 and Apstar 2 satellites and damaged AsiaSat 2.[2][3] The Long March 3B also experienced a catastrophic failure in 1996, veering off course shortly after liftoff and crashing into a nearby village. At least 6 people were killed on the ground, and the Intelsat 708 satellite was also destroyed.[4] A Long March 3 also experienced a partial failure in August 1996 during the launch of Chinasat-7.

United States embargo on Chinese launches

The involvement of U.S. companies in the Apstar 2 and Intelsat 708 investigations caused great controversy in the United States. In the Cox Report, the U.S. Congress accused Space Systems/Loral and Hughes of transferring information that would improve the design of Chinese rockets and ballistic missiles.[5] Although the Long March was allowed to launch its commercial backlog, the U.S. State Department has not approved any satellite export licenses to China since 1998. ChinaSat 8, which had been scheduled for launch in April 1999 on a Long March 3B rocket,[6] was placed in storage, sold to the Singapore company ProtoStar, and finally launched on a French rocket in 2008.[5]

From 2005 to 2012, Long March rockets launched ITAR-free satellites made by the European company Thales Alenia Space.[7] However, Thales Alenia was forced to discontinue its ITAR-free satellite line in 2013 after the U.S. State Department fined a U.S. company for selling ITAR components.[8] Thales Alenia had long complained that "every satellite nut and bolt" was being ITAR-restricted, and the European Space Agency accused the United States of using ITAR to block exports to China instead of protecting technology.[9] In 2016, an official at the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security confirmed that "no U.S.-origin content, regardless of significance, regardless of whether it’s incorporated into a foreign-made item, can go to China." The European aerospace industry is working on developing replacements for U.S. satellite components.[10]

Return to success

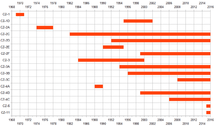

After the failures of 1992–1996, the troublesome Long March 2E was withdrawn from the market. Design changes were made to improve the reliability of Long March rockets. From October 1996 to April 2009, the Long March rocket family delivered 75 consecutive successful launches, including several major milestones in space flight:

- On October 15, 2003, the Long March 2F rocket successfully launched the Shenzhou 5 spacecraft, carrying China's first astronaut into space. China became the third nation with independent human spaceflight capability, after the Soviet Union/Russia and the United States.

- On June 1, 2007, Long March rockets completed their 100th launch overall.

- On October 24, 2007, the Long March 3A successfully launched (18:05 GMT+8) the "Chang'e 1" lunar orbiting spacecraft from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center.

The Long March rockets have subsequently maintained an excellent reliability record. Since 2010, Long March launches have made up 15–25% of all space launches globally. Growing domestic demand has maintained a healthy manifest. International deals have been secured through a package deal that bundles the launch with a Chinese satellite, circumventing the U.S. embargo.[11]

Payloads

The Long March is China's primary expendable launch system family. The Shenzhou spacecraft and Chang'e lunar orbiters are also launched on the Long March rocket. The maximum payload for LEO is 12,000 kilograms (CZ-3B), the maximum payload for GTO is 5,500 kg (CZ-3B/E). The next generation rocket – Long March 5 variants will offer more payload in the future.

Propellants

Long March 1's 1st and 2nd stage uses nitric acid and UDMH propellants, and its upper stage uses a spin-stabilized solid rocket engine.

Long March 2, Long March 3, Long March 4, the main stages and associated liquid rocket boosters use dinitrogen tetroxide as the oxidizing agent and UDMH as the fuel. The upper stages (third stage) of Long March 3 rockets use YF-73 and YF-75 engines, using Liquid hydrogen (LH2) as the fuel and Liquid oxygen (LOX) as the oxidizer.

The new generation of Long March rocket family, Long March 5, and its derivations Long March 6, Long March 7 will use LOX and kerosene as core stage and liquid booster propellant, with LOX and LH2 in upper stages.

Variants

The Long March rockets are organized into several series:

- Long March 1 rocket family

- Long March 2 rocket family

- Long March 3 rocket family

- Long March 4 rocket family

- Long March 5 rocket family

- Long March 6 rocket family

- Long March 7 rocket family

- Long March 11

Note:There is no Long March 10.

| Model | Status | Stages | Length (m) |

Max. diameter (m) |

Liftoff mass (t) |

Liftoff thrust (kN) |

Payload (LEO, kg) |

Payload (SSO, kg) | Payload (GTO, kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long March 1 | Retired | 3 | 29.86 | 2.25 | 81.6 | 1,020 | 300 | - | |

| Long March 1D | Retired | 3 | 28.22 | 2.25 | 81.1 | 1,101 | 930 | - | |

| Long March 2A | Retired | 2 | 31.17 | 3.35 | 190 | 2,786 | 1,800 | - | |

| Long March 2C | Active | 2 | 35.15 | 3.35 | 192 | 2,786 | 2,400 | - | |

| Long March 2D | Active | 2 | 33.667 (without shield) | 3.35 | 232 | 2,962 | 3,100 | - | |

| Long March 2E | Retired[12] | 2 (plus 4 Strap-on boosters) | 49.686 | 7.85 | 462 | 5,923 | 9,500 | 3,500 | |

| Long March 2E(A) | Canceled[13] | 2 (plus 4 Strap-on boosters) | 53.60 | N/A | 695 | 8,910 | 14,100 | - | |

| Long March 2F | Active | 2 (plus 4 Strap-on boosters) | 58.34 | 7.85 | 480 | 5,923 | 8,400 | 3,370 | |

| Long March 3 | Retired[12] | 3 | 43.8 | 3.35 | 202 | 2,962 | 5,000 | 1,500 | |

| Long March 3A | Active | 3 | 52.52 | 3.35 | 241 | 2,962 | 8,500 | 2,600 | |

| Long March 3B | Active | 3 (plus 4 Strap-on boosters) | 54.838 | 7.85 | 426 | 5,924 | 12,000 | 5,100 | |

| Long March 3B/E | Active | 3 (plus 4 Strap-on boosters) | 56.326 | 7.85 | 458.97 | ? | ? | 5,500 | |

| Long March 3B(A) | Active | 3 (plus 4 Strap-on boosters) | 62.00 | 7.85 | 580 | 8,910 | 13,000 | 6,000 | |

| Long March 3C | Active | 3 (plus 2 Strap-on boosters) | 55.638 | 7.85 | 345 | 4,443 | ? | 3,800 | |

| Long March 4A | Retired | 3 | 41.9 | 3.35 | 249 | 2,962 | 4,000 | 1,500 | |

| Long March 4B | Active | 3 | 44.1 | 3.35 | 254 | 2,971 | 4,200 | 2,200 | |

| Long March 4C | Active | 3 | 45.8 | 3.35 | 2,971? | 4,200 | 2,800 | ||

| Long March 5[14][15] | Active | 3 | 62 | 5 | 867 | N/A | 25,000 | 14,000 | |

| Long March 5B | In development | 53.7 | 5 | 837.5 | 22,000+ | ||||

| Long March 6[16][17] | Active | 3 | 29 | 3.35 | 103 | 500 | |||

| Long March 7 | Active | 2 | 57 | 3.35 | 594 | 7,200 | 13,500 | 7,000[18] | |

| Long March 8 | In development[19] | 3.35 | 7,600 | 4,500 | 2,500 | ||||

| Long March 9 | In development | 3 (plus 0-4

Strap-on boosters) |

93-110[20] | 10[21] | 3,000 | 140,000 | 50,000 | ||

| Long March 11 | Active | 3 solid( +1 liquid?) | 20.8 | ~2 | 58 | 700 | 350 |

| 2A | 2C | 2D | 2E | 2F | 3 | 3A | 3B | 3C | 4A | 4B | 4C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

Unflown

Long March 8

A new series of launch vehicles in study, which is geared towards SSO launches.[22] It will be partially reusable.[23]

Long March 9

The Long March 9 (LM-9, CZ-9, or Changzheng 9, Chinese: 长征九号) is a Chinese super-heavy carrier rocket that is currently in study. It is planned for a maximum payload capacity of 140,000 kg[24] to LEO, 50,000 kg to Lunar Transfer Orbit or 44,000 kg to Mars.[25][23] Its first flight is expected in 2030 in preparation for a lunar landing sometime in the 2030s;[26] a sample return mission from Mars has been proposed as first major mission.[23] It has been stated that around 70% of the hardware and components needed for a test flight are currently undergoing testing, with the first engine test to occur by the end of 2018. The proposed design would be a three-staged rocket, with the initial core having a diameter of 10 meters and use a cluster of four engines. Multiple variants on the rocket have been proposed, CZ-9 being the largest with four liquid-fuel boosters with the aforementioned LEO payload capacity of 140,000 kg, CZ-9A having just two boosters and a LEO payload capacity of 100,000 kg, and finally CZ-9B having just the core stage and a LEO payload capacity of 50,000 kg.[20] If produced, it would be classified as a super heavy-lift launch vehicle along with the Falcon Heavy, the retired American Saturn V and Soviet Energia rockets, the Space Launch System and BFR currently under development in the United States, and the KRK[27] under development in Russia.

Origins

The Long March 1 rocket is derived from earlier Chinese 2-stage IRBM DF-4, or Dong Feng 4 missile, and Long March 2, Long March 3, Long March 4 rocket families are derivatives of the Chinese 2-stage ICBMs DF-5, or Dong Feng 5 missile. However, like its counterparts in both the United States and in Russia, the differing needs of space rockets and strategic missiles have caused the development of space rockets and missiles to diverge. The main goal of a space rocket is to maximize payload, while for strategic missiles increased throw weight is much less important than the ability to launch quickly and to survive a first strike. This divergence has become clear in the next generation of Long March rockets, which use cryogenic propellants in sharp contrast to the next generation of strategic missiles, which are mobile and solid fuelled.

The next generation of Long March rocket, Long March 5 rocket family, is a brand new design, while Long March 6 and Long March 7 can be seen as derivations because they use the liquid rocket booster design of Long March 5 to build small-to-mid capacity launch vehicles.

Launch sites

There are four launch centers in China. They are:

- Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center

- Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center

- Wenchang Satellite Launch Center

- Xichang Satellite Launch Center

Most of the commercial satellite launches of Long March vehicles have been from Xichang Satellite Launch Center, located in Xichang, Sichuan province. Wenchang Satellite Launch Center in Hainan province is under expansion and will be the main launch center for future commercial satellite launches. Long March launches also take place from the more military oriented Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Gansu province from which the manned Shenzhou spacecraft also launches. Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center is located in Shanxi province and focuses on the launches of Sun-synchronous orbit satellites.

Commercial launch services

China markets launch services under the China Great Wall Industry Corporation.[28] Its efforts to launch communications satellites were dealt a blow in the mid-1990s after the United States stopped issuing export licenses to companies to allow them to launch on Chinese launch vehicles out of fear that this would help China's military. In the face of this, Thales Alenia Space built the Chinasat-6B satellite with no components from the United States whatsoever. This allowed it to be launched on a Chinese launch vehicle without violating U.S. ITAR restrictions.[29] The launch, on a Long March 3B rocket, was successfully conducted on July 5, 2007. A Chinese Long March 2D launched Venezuela's VRSS-1 (Venezuelan Remote Sensing Satellite 1) "Francisco de Miranda" on September 29, 2012.

See also

References

- ↑ Stevenson, Richard W. (September 16, 1988). "Shaky Start for Rocket Business". The New York Times.

- ↑ Zinger, Kurtis J. (2014). "An Overreaction that Destroyed an Industry: The Past, Present, and Future of U.S. Satellite Export Controls" (PDF).

- ↑ "CZ-2E Space Launch Vehicle". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ↑ Lan, Chen. "Mist around the CZ-3B disaster, part 1". The Space Review. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- 1 2 Zelnio, Ryan (January 9, 2006). "A short history of export control policy". The Space Review.

- ↑ Associate Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration (1999). "Commercial Space Transportation Quarterly Launch Report" (PDF).

- ↑ Harvey, Brian (2013). China in Space: The Great Leap Forward. New York: Springer. pp. 160–162. ISBN 9781461450436.

- ↑ Ferster, Warren (5 September 2013). "U.S. Satellite Component Maker Fined $8 Million for ITAR Violations". SpaceNews.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (9 August 2013). "Thales Alenia Space: U.S. Suppliers at Fault in "ITAR-free" Misnomer". Space News.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (April 14, 2016). "U.S. ITAR satellite export regime's effects still strong in Europe". SpaceNews.

- ↑ Henry, Caleb (August 22, 2017). "Back-to-back commercial satellite wins leave China Great Wall hungry for more". SpaceNews.

- 1 2 "CZ". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ↑ "CZ-2EA地面风载试验". 中国空气动力研究与发展中心. February 4, 2008. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- ↑ "cz5". SinoDefence. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008.

- ↑ "CZ-NGLV". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008.

- ↑ "China starts developing Long March 6 carrier rockets for space mission _English_Xinhua". News.xinhuanet.com. September 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "ChangZheng 6 (Long March 6) Launch Vehicle". SinoDefence.com. February 20, 2009. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ↑ "长征七号运载火箭". baidu.com.

- ↑ "hina is aiming to launch a new Long March 8 rocket". GBTIMES. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- 1 2 "China Aims for Humanity's Return to the Moon in the 2030s". www.popsci.com. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ↑ "China develops new rocket for manned moon mission: media". spacedaily.com.

- ↑ http://www.chinanews.com/mil/2015/03-07/7109962.shtml

- 1 2 3 "China reveals details for super-heavy-lift Long March 9 and reusable Long March 8 rockets". 5 July 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ↑ "First Look: China's Big New Rockets". AmericaSpace.

- ↑ 509. "梁小虹委员:我国重型运载火箭正着手立项 与美俄同步". people.com.cn.

- ↑ "China aims to outstrip NASA with super-powerful rocket".

- ↑ "РКК "Энергия" стала головным разработчиком сверхтяжелой ракеты-носителя". ria.ru. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ↑ "About CGWIC". CGWIC. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008.

- ↑ "China launches satellite despite restrictions". USA Today. July 6, 2007. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Long March (rocket family). |

.jpg)