Vulcan (rocket)

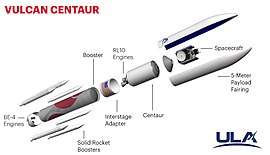

A simulated expanded view of the 562-configuration Vulcan Centaur rocket. | |

| Function | Partly-reusable launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | United Launch Alliance |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Size | |

| Height | 58.3 m (191 ft) |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft)[1] |

| Mass | 546,700 kg (1,205,300 lb) |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | 25,000 kg (56,000 lb)[2](Vulcan Heavy Centaur) |

| Payload to GTO | 15,000 kg (33,000 lb)[2](Vulcan Heavy Centaur) |

| Payload to GEO | 7,300 kg (16,000 lb)[2](Vulcan Heavy Centaur) |

| Associated rockets | |

| Comparable | |

| Launch history | |

| Status | In development |

| Launch sites |

Cape Canaveral SLC-41 Vandenberg SLC-3E[3] |

| First flight | Mid-2020 (planned)[2] |

| Boosters | |

| No. boosters | 0–6 |

| Motor | GEM 63XL[4] |

| Thrust | 2,201.7 kN (495,000 lbf) |

| Fuel | HTPB |

| First stage | |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Engines | 2× BE-4 |

| Thrust | 4,900 kN (1,100,000 lbf) |

| Fuel | CH4 / LOX |

| Second stage – Centaur (initial flights, late-2010s) | |

| Engines | 2× RL10-C[5][6][7] |

| Thrust | 207.6 kN (46,700 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 448.5 seconds (4.398 km/s) |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOX |

| Second stage – ACES (proposed, mid-2020s) | |

| Engines | 4× RL10-C or 1× BE-3 engine (TBC) |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOx |

The Vulcan rocket, also known as the Vulcan Centaur,[8] is an American heavy-payload launch vehicle under development since 2014 by United Launch Alliance (ULA), funded by a public–private partnership with the U.S. government. ULA expects the first launch of the new rocket to occur no earlier than mid-2020.[9]

Through the first several years of the development project, the ULA board of directors had made only short-term (quarterly) funding commitments to the rocket program, and it remains unclear if long-term private funding will be available to finish the project. As of October 2018, the US government had committed approximately US$1.2 billion to Vulcan development.[10][11]

History

United Launch Alliance had considered several launch vehicle concepts in the decade since the company was formed in 2006. Various concepts for derivative vehicles based on the Atlas and Delta lines of launch vehicles they inherited from their predecessor companies were presented to the U.S. government for funding. None were funded beyond concept stage.

In early 2014, geopolitical and U.S. political considerations involving international sanctions during the Ukrainian crisis, led to an effort by ULA to consider possibly replacing the Russian-supplied RD-180 engine used on the first stage booster of the Atlas V. Formal study contracts were issued by ULA in June 2014 to several U.S. rocket engine suppliers.[12] ULA was also facing competition from SpaceX, then seen to affect ULA's core national security market of U.S. military launches, and by July 2014 the United States Congress was debating whether to legislate a ban on future use of the RD-180.[13]

New first stage booster

In September 2014, ULA announced that it had entered into a partnership with Blue Origin to develop the BE-4 liquid oxygen (LOX) and liquid methane (CH4) engine to replace the RD-180 on a new first stage booster. The Blue engine was already in its third year of development by Blue Origin, and ULA said it expected the new stage and engine to start flying no earlier than 2019.[14] Two of the 2,400-kilonewton (550,000 lbf)-thrust BE-4 engines were to be used on a new launch vehicle booster.[12] ULA referred to the successor concept vehicle as a "next generation launch system"[15] and used that descriptor into early 2015.[14]

In October 2014, ULA announced a major restructuring of company processes and workforce to reduce launch costs by half. One of the reasons given for the restructuring and new cost reduction goals was new competition in the launch market from SpaceX.[15][13] ULA planned to have preliminary design ideas in place for a blending of its existing Atlas V and Delta IV technologies by the end of 2014, to build a successor to the Atlas V that would allow the company to halve Atlas V launch costs.[15] A part of the restructuring effort was described as the effort to co-develop the alternative BE-4 engine with Blue Origin for the new launch vehicle.[16]

Unveiling

On 13 April 2015, CEO Tory Bruno unveiled the new ULA launch vehicle as the Vulcan at the 31st Space Symposium, a new two-stage-to-orbit (TSTO) rocket that would be rolled out incrementally. The Vulcan name was chosen after an online poll to select the name. Vulcan Inc. stated that it held the trademark on the name and contacted ULA.[17] ULA stated its goal was to sell a "barebones Vulcan" for half the price of a basic Atlas V rocket, which sold for about $164 million as of 2015. Addition of strap-on boosters for heavier satellites would increase the price.[18] At the announcement, the ULA board had not yet approved the new launch vehicle, with first launch planned in 2019.[13]

ULA put forth an "incremental approach" to rolling out the vehicle and its technologies,[19] with Vulcan deployment beginning with the first stage, based on the Delta IV's fuselage diameter and production process, expected to use two BE-4 engines. The Aerojet Rocketdyne AR1 engine was retained by ULA as a contingency option. In late September 2018, ULA announced that the BE-4 engine was to power the first stage.[20] The first stage will be able to optionally use from one to six solid rocket boosters (SRBs) for added liftoff thrust,[21] launch a heavier payload than the highest-rated Atlas V in the six-SRB configuration.

ULA announced a feature they could subsequently develop which would make the first stage partly reusable: allowing the engines to detach from the vehicle after main engine cutoff, descend through the atmosphere with a heat shield and parachute, being captured by a helicopter in mid-air.[17] ULA estimated that reusing the engines in this way would reduce the cost of the first stage propulsion by 90%, where propulsion is 65% of the total first stage cost.[22] Initial configurations of Vulcan were intended then to use the same Centaur upper stage as the Atlas V, with its existing RL10 engines, while a later advanced cryogenic upper stage — called the Advanced Cryogenic Evolved Stage (ACES) — was conceptually planned for full development by ULA in the late 2010s. ACES would be LOX and liquid hydrogen (LH2) powered by one to four rocket engines yet to be selected, and would include the Integrated Vehicle Fluids technology that could allow much longer on-orbit life of the upper stage, measured in weeks rather than hours.[23][19]

In May 2015, ULA released a chart showing a potential future Vulcan Heavy three-core launch vehicle concept with 23,000 kg (50,000 lb)-payload capacity to geostationary transfer orbit, while a single-core Vulcan 561 with the ACES upper stage would have 15,100 kg (33,200 lb) capacity to the same orbit.[24]

In September 2015, ULA and Blue Origin announced an agreement to expand production capabilities to include the BE-4 rocket engine then in development and test. However, ULA also reconfirmed that the decision on the BE-4 versus the AJR AR1 would not be made until late 2016, with maiden flight of Vulcan no earlier than 2019.[25]

Engine testing and design optimization

As of January 2016, full-engine testing of the BE-4 was planned to begin prior to the end of 2016,[26] while ULA was designing two versions of the Vulcan first stage, one using the BE-4 with a 5.4 m (18 ft) outer diameter to support the less-dense methane fuel and an AR1 design with the same 3.81 m (12.5 ft) diameter as Atlas V for the denser RP-1 (kerosene) fuel.[27]

ULA completed the Preliminary Design Review (PDR) in March 2016 for one of the two parallel designs: the Vulcan/Centaur launch vehicle with dual Blue Origin BE-4 engines. The PDR "confirms that the design meets the requirements for the diverse set of missions it will support."[28] In the event, BE-4 engine testing did not begin until 2017.[29]

In April 2016, ULA CEO Tory Bruno stated that the company was targeting a complete launch services price of $99 million for base Vulcan with no solid rocket boosters.[30] Also the ULA team was to be reduced by about one quarter of its legacy workforce, or more than 800 employees, by end 2017 in order to better compete with SpaceX and Blue Origin offerings in the US launch market.[30] In October 2017, ULA announced that Bigelow Aerospace's B330 would be flown on a Vulcan 562 configuration rocket rather than the previously planned Atlas V.[31]

A delay was announced in January 2018 pushing first launch back from 2019 to mid-2020.[9] Also announced was an upgrade to the Centaur second stage to include up to four RL10 engines, to be called Centaur V.[32] While a tri-core Vulcan Heavy with a payload of 23,000 kg (50,000 lb) had been conceptualized in 2015,[24] ULA clarified that it would not build a multi-core configuration as the upgrades to the Centaur second stage would allow a single core Vulcan Centaur to lift "30% more" than a Delta IV Heavy.[33] By March 2018, ULA had begun to publicly refer to the new Vulcan first stage with the Centaur V second stage as the Vulcan Centaur.[8]

In May 2018, ULA selected Aerojet Rocketdyne's RL10 engine for the Vulcan Centaur upper stage.[34]

In late September 2018, ULA announced that the Blue Origin BE-4 engine is to power the first stage of the Vulcan.[2]

Funding

Vulcan is being funded by a combination of government and private funds.[10][8] The initial private funding for Vulcan development, during the first 18 months after announcement in October 2014, was approved only for the short term. By April 2015, it became public that the United Launch Alliance board of directors — composed entirely of executives from Boeing and Lockheed Martin — was approving development funding on only a quarter-by-quarter basis.[35] Funding remained limited to quarterly approvals in June 2015, and Lockheed Martin was actively working to use the funding limitation to get the US Congress to change existing law and allow extension of ULA ability to acquire RD-180 engines for the Atlas V.[36] In March 2016, executives from ULA indicated that the practice of quarter-by-quarter investment for Vulcan development would continue.[10]

By March 2016, the US Air Force had committed up to US$202 million of funding for Vulcan development. ULA has not "put a firm price tag on [the total cost of Vulcan development but ULA CEO Tory Bruno has] said new rockets typically cost $2 billion, including $1 billion for the main engine."[10] ULA Board of Directors member, and Boeing executive (President of Boeing's Network and Space Systems (N&SS) division), Craig Cooning said in April 2016 that he is confident that the US Air Force will invest in further funding of Vulcan development costs.[37]

In September 2017 the bill for the proposed National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 carried language in the House version inserted by Congressman Mike Rogers. This language would limit the US DoD, and hence the US Air Force, from allocating funding to ULA for the Vulcan rocket for the fiscal year 2018.

In March 2018, ULA CEO Tory Bruno said "Vulcan Centaur [had been] 75 percent privately funded" up to that time.[8] In 2016, the US Congress had authorized the USAF to "sign deals with the space industry to co-finance the development of new rocket propulsion systems. The program known as the Launch Service Agreement (LSA) fits the Air Force's broader goal to get out of the business of "buying rockets" and instead acquire end-to-end services from companies. The Air Force signed cost-sharing partnerships with [launch vehicle company] ULA, [launch vehicle and rocket engine manufacturers] SpaceX [and] Orbital ATK, and [with rocket engine supplier] Aerojet Rocketdyne. The original request for proposals noted the Air Force wants to "leverage commercial launch solutions in order to have at least two domestic, commercial launch service providers." In October 2018, ULA was awarded $967 million to develop a prototype Vulcan launch system.[38]

Design approach and description

ULA took an incremental approach to the development of their first launch vehicle design[19] utilizing various technologies previously developed by its two parent companies: choosing significant Boeing Delta IV technology as well as Lockheed Martin Atlas technology. In addition, ULA began an engine selection competition in 2015 between engine suppliers Aerojet Rocketdyne and Blue Origin for both the booster and upper stages. It continued the tradition of is parent companies to accept a large amount of development funding from the US government, while adding elements of private capital to fund a portion of development cost.[19][13][25] The engine competition continued into 2018.

The first stage propellant tanks are derived from those of the Delta IV, using two of the 2,400-kilonewton (550,000 lbf)-thrust BE-4 engines.[12][39][40] At announcement in 2014, the BE-4 engine was already in its third year of development by Blue Origin, and ULA expected the new stage and engine to start flying no earlier than 2019.

Vulcan initially planned to use an upgraded variant of the Centaur upper stage used on Atlas V, with a plan to later upgrade to ACES.[41] The design also uses a variable number of optional solid rocket boosters, called the Graphite-Epoxy Motor (GEM) 63XL, derived from the new solid boosters planned for Atlas V.[42] With a 4-meter diameter payload fairing it can use up to four SRBs, and with a 5-meter fairing it can use up to six SRBs. The first stage can optionally have from zero to six solid rocket boosters (SRBs).[21]

In August 2016 ULA's President and CEO said they intend to human rate both the Vulcan and ACES.[43]

From 2015–2018, ULA designed two versions of the Vulcan first stage, one using the BE-4 with a 5.4 m (18 ft) outer diameter to support the less-dense methane fuel and an alternative AR1 design with the same 3.81 m (12.5 ft) diameter as Atlas V for the denser RP-1 (kerosene) fuel.[27]

Engine choice

A competition among engine vendors, Blue Origin and Aerojet Rocketdyne has been underway since approximately 2014, with final engine selection originally slated for 2017[44] but subsequently moved to 2018.

In April 2017, just as a major series of ground tests of the Blue Origin BE-4 were set to occur over the summer, ULA indicated that Blue continued to lead, but the final selection would not be made until after the test series is complete, particularly a variety of tests aimed at characterizing any combustion instability in the design.[44] Blue Origin experienced a test anomaly on 13 May 2017 reporting that they lost a set of BE-4 powerpack hardware.[45]

The BE-4 was first test-fired, at 50 percent thrust for three seconds, in October 2017.[29] As of February 2018, Aerojet Rocketdyne is asking for additional funds from USAF to complete work on the AR-1 engine.[46]

In late September 2018, ULA selected the BE-4 to power the Vulcan first stage. [47]

References

- ↑ Peller, Mark. "United Launch Alliance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "United Launch Alliance Building Rocket of the Future with Industry-Leading Strategic Partnerships ULA Selects Blue Origin Advanced Booster Engine for Vulcan Centaur Rocket System". United Launch Alliance. 27 September 2018.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (12 October 2015). "ULA selects launch pads for new Vulcan rocket". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Rhian, Jason. "ULA selects Orbital ATK's GEM 63/63XL SRBs for Atlas V and Vulcan Boosters". Spaceflight Insider. Retrieved 2015-09-25.

- ↑ @ulalaunch (27 September 2018). "Our partnerships w/ @BlueOrigin as well as @AerojetRDyne @NorthropGrumman L-3 Avionics & @RUAGSpace will allow this next-gen American rocket to affordably transform the future of space launch!" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ "Vulcan Centaur". United Launch Alliance. Retrieved 2018-10-02.

- ↑ "United Launch Alliance Selects Aerojet Rocketdyne's RL10 Engine for Next-generation Vulcan Centaur Upper Stage". United Launch Alliance website. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Erwin, Sandra (25 March 2018). "Air Force stakes future on privately funded launch vehicles. Will the gamble pay off?". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2018-06-24.

- 1 2 @jeff_foust (18 January 2018). "Tom Tshudy, ULA: with Vulcan we plan to maintain reliability and on-time performance of our existing rockets, but at a very affordable price. First launch mid-2020" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- 1 2 3 4 Gruss, Mike (2016-03-10). "ULA's parent companies still support Vulcan … with caution". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ↑ Erwin, Sandra (2018-10-10). "Air Force awards launch vehicle development contracts to Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, ULA - SpaceNews.com". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- 1 2 3 Ferster, Warren (2014-09-17). "ULA To Invest in Blue Origin Engine as RD-180 Replacement". Space News. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Gruss, Mike (2015-04-24). "Evolution of a Plan : ULA Execs Spell Out Logic Behind Vulcan Design Choices". Space News. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- 1 2 Fleischauer, Eric (7 February 2015). "ULA's CEO talks challenges, engine plant plans for Decatur". Decatur Daily. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- 1 2 3 Avery, Greg (2014-10-16). "ULA plans new rocket, restructuring to cut launch costs in half". Denver Business Journal. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ Delgado, Laura M. (2014-11-14). "ULA's Tory Bruno Vows To Transform Company". SpacePolicyOnline.com. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- 1 2 Boyle, Alan (2015-04-13). "United Launch Alliance Boldly Names Its Next Rocket: Vulcan!". NBC. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (22 April 2015). "ULA needs commercial business to close Vulcan rocket business case". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Gruss, Mike (2015-04-13). "ULA's Vulcan Rocket To be Rolled out in Stages". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ Mehta, Aaron (2018-09-27). "ULA selects Blue Origin engine to power launch vehicle". Defense News. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- 1 2 United Launch Alliance Unveils America’s New Rocket – Vulcan: Innovative Next Generation Launch System will Provide Country’s Most Reliable, Affordable and Accessible Launch Service. April 2015

- ↑ Ray, Justin (14 April 2015). "ULA chief explains reusability and innovation of new rocket". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ "America, meet Vulcan, your next United Launch Alliance rocket". Denver Post. 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- 1 2 Tory Bruno [@torybruno] (5 May 2015). "ULA Full Spectrum Lift Capability" (Tweet). Retrieved 8 May 2015 – via Twitter.

- 1 2 "Boeing, Lockheed Differ on Whether to Sell Rocket Joint Venture". Wall Street Journal. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- ↑ Berger, Brian (2016-01-23). "Launch. Land. Repeat: Blue Origin posts video of New Shepard's Friday flight". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

Also this year, we’ll start full-engine testing of the BE-4

- 1 2 de Selding, Peter B. (2016-03-16). "ULA intends to lower its costs, and raise its cool, to compete with SpaceX". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

Methane rocket has a lower density so we have a 5.4 meter design outside diameter, while drop back to the Atlas V size for the kerosene AR1 version. ... Aerojet Rocketdyne AR1 ... haven't built any hardware yet ... additive manufacturing is revolutionizing complex casting ... Aerojet is investing a little bit of their own money. Primarily they are counting on the government's RPS (Rocket Propulsion System) contracts to drive the funding.

- ↑ "United Launch Alliance Completes Preliminary Design Review for Next-Generation Vulcan Centaur Rocket". Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- 1 2 Berger, Eric (19 October 2017). "Blue Origin just sent a jolt through the aerospace industry". Ars Technica. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- 1 2 "United Launch Alliance to lay off up to 875 by end of 2017: CEO". Reuters. 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ "Bigelow Aerospace and United Launch Alliance Announce Agreement to Place a B330 Habitat in Low Lunar Orbit" (Press release). United Launch Alliance. October 17, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Vulcan Centaur". ULA. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ↑ ToryBruno (President & CEO of ULA). "Vulcan Heavy?". Reddit.com. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ Tribou, Richard (11 May 2018). "ULA chooses Aerojet Rocketdyne over Blue Origin for Vulcan's upper stage engine". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ Avery, Greg (2015-04-16). "The fate of United Launch Alliance and its Vulcan rocket may lie with Congress" (Denver Business Journal). Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "AIRSHOW-Lockheed says rocket launch venture urgently needs U.S. law waiver". Yahoo Finance, June 14, 2015.

- ↑ Host, Pat (2016-04-12). "Cooning Confident Air Force Will Invest In Vulcan Development". Defense Daily. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ↑ Erwin, Sandra (2018-10-10). "Air Force awards launch vehicle development contracts to Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, ULA - SpaceNews.com". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ Mike Gruss (13 April 2015). "ULA's Vulcan Rocket To be Rolled out in Stages". Space News.

- ↑ Butler, Amy (11 May 2015). "Industry Team Hopes To Resurrect Atlas V Post RD-180". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Bruno, Tory (10 October 2017). "Building on a successful record in space to meet the challenges ahead". Space News.

- ↑ Jason Rhian (23 September 2015). "ULA selects Orbital ATK's GEM 63/63 XL SRBs for Atlas V and Vulcan boosters". Spaceflight Insider.

- ↑ Tory Bruno. ""@A_M_Swallow @ULA_ACES We intend to human rate Vulcan/ACES"". Twitter.com. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- 1 2 "Bruno: Vulcan engine downselect is Blue's to lose". Space News, April 5, 2017

- ↑ "Blue Origin suffers BE-4 testing mishap". Space News, May 15, 2017.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (16 February 2018). "Air Force and Aerojet Rocketdyne renegotiating AR1 agreement". Space News.

- ↑ "United Launch Alliance Building Rocket of the Future with Industry-Leading Strategic Partnerships". 28 Sep 2018.

External links

- Official website

- ISPCS 2015 Keynote, Mark Peller, Program Manager of Major Development at ULA and Vulcan Program Manager discusses Vulcan, 8 October 2015. Key discussion of Vulcan is at 12:20 point in video.