Spacelab

Spacelab was a reusable laboratory used on certain spaceflights flown by the Space Shuttle. The laboratory comprised multiple components, including a pressurized module, an unpressurized carrier and other related hardware housed in the Shuttle's cargo bay. The components were arranged in various configurations to meet the needs of each spaceflight.

Spacelab components flew on a total of 32 Shuttle missions. Spacelab allowed scientists to perform experiments in microgravity in earth orbit. There was a variety of Spacelab-associated hardware, so a distinction can be made between the major Spacelab program missions with European scientists running missions in the Spacelab habitable module, missions running other Spacelab hardware experiments, and other STS missions that used some component of Spacelab hardware. There is some variation in counts of Spacelab missions, in part because there were different types of Spacelab missions with a large range in the amount of Spacelab hardware flown and the nature of each mission. There were at least 22 major Spacelab missions between 1983 and 1998, and Spacelab hardware was used on a number other missions, with some of the Spacelab pallets being flown as late as 2008.[1]

Background and History

In August 1973, NASA and ESRO (now European Space Agency or ESA) signed a Memorandum of Understanding to build a science laboratory for use on Space Shuttle flights.[2] Construction of Spacelab was started in 1974 by the ERNO (subsidiary of VFW-Fokker GmbH, after merger with MBB named MBB/ERNO, and part of EADS SPACE Transportation since 2003). The first lab module, LM1, was donated to NASA in exchange for flight opportunities for European astronauts. A second module, LM2, was bought by NASA for its own use from ERNO.[3]

Construction on the Spacelab modules began in 1974 by what then the company ERNO-VFW-Fokker.[4]

Spacelab is important to all of us for at least four good reasons. It expanded the Shuttle's ability to conduct science on-orbit manyfold. It provided a marvelous opportunity and example of a large international joint venture involving government, industry, and science with our European allies. The European effort provided the free world with a really versatile laboratory system several years before it would have been possible if the United States had had to fund it on its own. And finally, it provided Europe with the systems development and management experience they needed to move into the exclusive manned space flight arena.

— NASA Administrator, Spacelab: An International Success Story[5]

In the early 1970s NASA shifted its focus from the Lunar missions to the Space Shuttle, and also space research.[6] The NASA Administrator at the time moved the focus from a new space station to space laboratory for planned Space Shuttle.[7] This would allow technologies for future space stations to be researched and harness the capabilites of the Space Shuttle for research.[8]

Spacelab was produced by a consortium of ten European countries including:[9]

Components

In addition to the laboratory module, the complete set also included five external pallets for experiments in vacuum built by British Aerospace (BAe) and a pressurized Igloo containing the subsystems needed for the pallet-only flight configuration operation. Eight flight configurations were qualified, though more could be assembled if needed.

Spacelab consisted of a variety of interchangeable components, with the major one being manned laboratory that could be flown in Space Shuttle orbiter's bay and returned to Earth.[10] However, the habitable module did not have to be flown to conduct a Spacelab-type mission and there was a variety of pallets and other hardware supporting space research.[11] The Habitable module expanded the volume for astronauts to work in a shirt sleeve environment and had space for equipment racks and related support equipment.[12] When the habitable module was not used, some of the support equipment for the pallets could be housed in the smaller Igloo, a pressurized cylinder connected to the Space Shuttle orbiter crew area.[13]

Spacelab mission typically supported multiple experiments, and the Spacelab-1 mission had experiments in the fields of space plasma physics, solar physics, atmosphere physics, astronomy, and Earth observation.[14] The selection of appropriate modules was part of mission planning for Spacelab Shuttle missions, and for example, a mission might need less habitable space and more pallets, or vice versa.[15]

Habitable module

The Spacelab Module comprises a cylindrical main laboratory configurable as Short or Long Module flown in the rear of the Space Shuttle cargo bay, connected to the crew compartment by a tunnel. The laboratory had an outer diameter of 4.12 meters (13.5 ft), and each segment a length of 2.7 meters (8.9 ft). Most of the time two segments were used in forming the Long Module configuration.

A pressurized tunnel connected the Space Shuttle orbiter main cabin to Spacelab Habitable Module(s), with a connection point at the mid-deck.[16] There was two different length tunnels depending on the location of the HM in the payload bay.[17] When the Habitable Module was not used, but additional space was needed for support equipment another structure called the Igloo could be used.[18]

The bigger configuration of the Habitation module consisted of the Core module and Experiment module.[19] It was also possible to operate Spacelab experiments from the Space Shuttle orbiter aft flight deck.[20]

Two habitable modules were built, named LM1 and LM2. LM2 is now on display in the Bremenhalle exhibition in the Bremen Airport of Bremen, Germany. LM1 is now on display at the Udvar-Hazy center at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum behind the Space Shuttle Discovery.

Pallet

The Spacelab Pallet is a U-shaped platform for mounting instrumentation, large instruments, experiments requiring exposure to space, and instruments requiring a large field of view, such as telescopes. The pallet has several hard points for mounting heavy equipment. The pallet can be used in single configuration or stacked end to end in double or triple configurations. Up to five pallets can be configured in the Space Shuttle cargo bay by using a double pallet plus triple pallet configurations.

The Spacelab Pallet used to transport both Canadarm-2 and Dextre to the International Space Station is currently at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, on loan from NASA through the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).[21]

A Spacelab Pallet was transferred to the Swiss Museum of Transport for permanent display on 5 March 2010. The Pallet, nicknamed Elvis, was used during the eight-day STS-46 mission, 31 July – 8 August 1992, when ESA astronaut Claude Nicollier was on board Shuttle Atlantis to deploy ESA's European Retrievable Carrier (Eureca) scientific mission and the joint NASA/Italian Space Agency Tethered Satellite System (TSS-1). The Pallet carried TSS-1 in the Shuttle's cargo bay.[22]

Another Spacelab pallet is on display at the U.S. National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC[23] Overall there was ten space-flown Spacelab pallets.[24]

Igloo

On spaceflight where a habitable module was not flown, but pallets were flown, a pressurized cylinder known as the igloo carried the subsystems needed to operate the Spacelab equipment.[25] The Igloo was 10 feet tall, had a diameter of 5 feet, and weighed 2,500 lb.[26] Two igloo units were manufactured, both by Belgium company SABCA, and both were used on spaceflight.[26] An igloo component was flown on Spacelab 2, Astro-1, ATLAS-1, ATLAS-2, ATLAS-3, and Astro-2.[26]

A Spacelab Igloo is on display at the James S. McDonnell Space Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in the United States.[27]

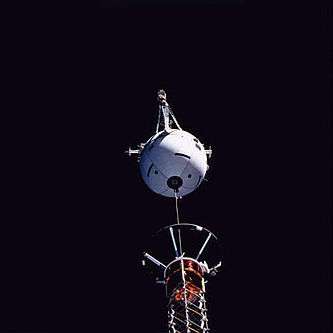

Instrument Pointing System

The IPS was a gimbaled pointing device, capable of aiming telescopes, cameras, or other instruments.[28] IPS was used on three different space shuttle missions between 1985 and 1995.[28] IPS was manufactured by Dornier, and two units were made.[28] The IPS was primarily constructed out of aluminum, steel, and multi-layer insulation.[29]

IPS would be mounted inside the payload bay of the Space Shuttle Orbiter, and could provide gimbaled 3-axis pointing.[30] It was designed for a pointing accuracy of less than 1 arcsecond (a unit of degree), and three pointing modes including Earth, Sun, and Stellar focused modes.[31] The IPS was mounted on a pallet exposed to outer space in the payload bay.[31]

IPS missions:[28]

- Spacelab 2, a.k.a. STS-51-F launched 1985

- Astro-1, a.k.a. STS-35 launched 1990[32]

- Astro-2, a.k.a. STS-67 launched 1995

The Spacelab 2 mission flew the Infrared Telescope (IRT), which was a 15.2 cm aperture helium-cooled infrared telescope, observing light between wavelengths of 1.7 to 118 μm.[33] IRT collected infrared data on 60% of the galactic plane.[34]

Instrument Pointing System (IPS)

Instrument Pointing System (IPS) IPS at work above the sky on Astro-2, 1995

IPS at work above the sky on Astro-2, 1995 Dornier Instrument Pointing System at the Smithsonian Museum (Udvar Hazy Center)

Dornier Instrument Pointing System at the Smithsonian Museum (Udvar Hazy Center)

List of parts

Other Spacelab elements include the tunnel, and the Instrument Pointing System (IPS) tailored to the pallet interfaces for precise pointing to space or earth targets.

Spacelab was a modular re-usable space-hardware system designed for about 50 uses over ten years, with a contract signed for its construction in 1974. It had components like a manned orbiting observatory in the Shuttle-bay, to various logistical hardware for experiments in space, to astronomy, and Earth observation.

The system had some unique features including an intended two-week turn-around time (for the original Space Shuttle launch turn-around time) and the roll-on-roll-off for loading in aircraft (Earth-transportation).

Examples of Spacelab components or hardware:

- EVA Airlock

- Tunnel[35]

- Tunnel adapter[36]

- Igloo

- Spacelab module[37]

- Electrical Ground Support Equipment

- Mechanical Ground Support Equipment

- Electrical Power Distribution Subsystem

- Command and Data Management Subsystem

- Environmental Control Subsystem

- Instrument Pointing System

- Pallet Structure

- Multi-Purpose Experiment Support Structure (MPESS)

The Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) assembly was not Spacelab hardware, strictly speaking. However, it was used most often on Spacelab flights. Also, later on NASA used a module called Spacehab

Spacelab missions

_Illustration.jpg)

Spacelab components flew on 22 Space Shuttle missions from November 1983 to April 1998.[40] The Spacelab components were decommissioned in 1998, except the pallets. Science work was moved to the International Space Station and Spacehab module, a pressurized carrier similar to the Spacelab Module. A Spacelab Pallet was recommissioned in 2002 for flight on STS-99. The "Spacelab Pallet – Deployable 1 (SLP-D1) with Canadian Special Purpose Dexterous Manipulator, Dextre" was launched on STS-123. "Spacelab Pallet – Deployable 2 (SLP-D2)" was scheduled for STS-127. The Spacelab components were used on 32 Shuttle missions in total.

The habitable modules were flown on 16 Space Shuttle missions in the 1980s and 1990s.[41]

| Mission name | Orbiter | Launch date | Spacelab mission name |

Pressurized module |

Unpressurized modules |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STS-2 | Columbia | November 12, 1981 | OSTA-1 | 1 Pallet[42] | |

| STS-3 | Columbia | March 22, 1982 | OSS-1 | 1 Pallet[43] | |

| STS-9 | Columbia | November 28, 1983 | Spacelab 1 | Module LM1 | 1 Pallet |

| STS-41-G | Challenger | October 5, 1984 | OSTA-3 | Pallet[44] | |

| STS-51-B | Challenger | April 29, 1985 | Spacelab 3 | Module LM1 | MPESS |

| STS-51-F | Challenger | July 29, 1985 | Spacelab 2 | Igloo | 3 Pallets + IPS |

| STS-61-A (D1) | Challenger | October 30, 1985 | Spacelab D1 | Module LM2 | MPESS |

| STS-35 | Columbia | December 2, 1990 | Astro-1 | Igloo | 2 Pallets + IPS |

| STS-40 | Columbia | June 5, 1991 | SLS-1 | Module LM1 | |

| STS-42 | Discovery | January 22, 1992 | IML-1 | Module LM2 | |

| STS-45 | Atlantis | March 24, 1992 | ATLAS-1 | Igloo | 2 Pallets |

| STS-50 | Columbia | June 25, 1992 | USML-1 | Module LM1 | EDO |

| STS-46 | Atlantis | July 31, 1992 | TSS-1 | 1 Pallet[22] | |

| STS-47 (J) | Endeavour | September 12, 1992 | Spacelab-J | Module LM2 | |

| STS-52 | Columbia | October 22, 1992 | USMP-1 | 2 MPESS | |

| STS-56 | Discovery | April 8, 1993 | ATLAS-2 | Igloo | 1 Pallet |

| STS-55 (D2) | Columbia | April 26, 1993 | Spacelab D2 | Module LM1 | Unique Support Structure (USS) |

| STS-58 | Columbia | October 18, 1993 | SLS-2 | Module LM2 | EDO |

| STS-62 | Columbia | March 4, 1994 | USMP-2 | 2 MPESS + EDO | |

| STS-59 | Endeavour | April 9, 1994 | SRL-1 | 1 Pallet | |

| STS-65 | Columbia | July 8, 1994 | IML-2 | Module LM1 | EDO |

| STS-64 | Discovery | September 9, 1994 | LITE | 1 Pallet[45] | |

| STS-68 | Endeavour | September 30, 1994 | SRL-2 | 1 Pallet | |

| STS-66 | Atlantis | November 3, 1994 | ATLAS-3 | Igloo | 1 Pallet |

| STS-67 | Endeavour | March 2, 1995 | Astro-2 | Igloo | 2 Pallets + IPS + EDO |

| STS-71 | Atlantis | June 27, 1995 | Spacelab-Mir | Module LM2 | |

| STS-73 | Columbia | October 20, 1995 | USML-2 | Module LM1 | EDO |

| STS-75 | Columbia | February 22, 1996 | TSS-1R / USMP-3 | 1 Pallet[44] + 2 MPESS + EDO | |

| STS-78 | Columbia | June 20, 1996 | LMS | Module LM2 | EDO |

| STS-82 | Discovery | February 21, 1997 | Pallet[44] | ||

| STS-83 | Columbia | April 4, 1997 | MSL-1 | Module LM1 | EDO |

| STS-94 | Columbia | July 1, 1997 | MSL-1R | Module LM1 | EDO |

| STS-87 | Columbia | November 19, 1997 | USMP-4 | 2 MPESS + EDO | |

| STS-90 | Columbia | April 17, 1998 | Neurolab | Module LM2 | EDO |

| STS-99 | Endeavour | February 11, 2000 | SRTM | Pallet |

Mission name acronyms:

- ATLAS: Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science

- Astro: Not an acronym; abbreviation for "astronomy"

- IML: International Microgravity Laboratory

- LITE: Lidar In-space Technology Experiment

- LMS: Life and Microgravity Sciences

- MSL: Materials Science Laboratory

- SLS: Spacelab Life Sciences

- SRL: Space Radar Laboratory

- TSS: Tethered Satellite System

- USML: U.S. Microgravity Laboratory

- USMP: U.S. Microgravity Payload

Besides contributing to ESA missions, Germany and Japan each funded their own Space Shuttle and Spacelab missions. Although superficially similar to other flights, they were actually the first and only non-U.S. and non-European manned space missions with complete German and Japanese control.

The first West German mission Deutschland 1 (Spacelab-D1, DLR-1, NASA designation STS-61-A) took place in 1985. A second similar mission, Deutschland 2 (Spacelab-D2, DLR-2, NASA designation STS-55), was first planned for 1988, but due to the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, was delayed until 1993. It became the first German manned space mission after German reunification.[46]

The only Japan mission, Spacelab-J (NASA designation STS-47), took place in 1992.

Other missions

Cancelled missions

Spacelab-4, Spacelab-5 and other planned Spacelab missions were cancelled due to the late development of the Shuttle and the Challenger disaster.

Gallery

Legacy

The legacy of Spacelab lives on in the form of the MPLMs and the systems derived from it. These systems include the ATV and Cygnus spacecraft used to transfer payloads to the International Space Station, and the Columbus, Harmony and Tranquility modules of the International Space Station.[47][48]

Spacelab 2 mission surveyed 60% of the galactic plane in infrared in 1985.[34]

Spacelab was an extremely large program, and this was enhanced by different experiments and multiple payloads and configurations over two decades. For example, in a subset of just one part of the Spacelab 1 (STS-9) mission, no less than 8 different imaging systems were flown into space. Including those experiments, there was a total of 73 separate experiments across different disciplines on the Spacelab 1 flight alone. Spacelab missions conducted experiments in materials, life, solar, astrophysics, atmospheric, and Earth science.[49]

Spacelab represents a major investment on the order of one billion dollars from our European friends. But its completion marks something equally important: The commitment of a dogged, dedicated, and talented team drawn from ESA Governments, universities, and industries who stuck with it for a decade and saw the project through. We are proud of your perseverance and congratulate you on your success.

— NASA Administrator, 1982[50]

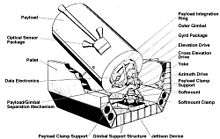

Diagram 1

1-transitional and connecting tunnel between orbiter and Spacelab.

2-payload space hinges

3-footstalks

4-experimental unit

5-hyperbaric (?) modules

6-external platform

7-infrared telescope

8-device for research Earth´s magnetic field

9-payload space of orbiter

10-back side of front part of orbiter

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ esa. "Spacelab".

- ↑ Lord 1987, pp. 24–28.

- ↑ Space Transportation System – HAER No. TX-116 – p. 46. Quote: "..Later, NASA purchased LM2, the second lab"

- ↑ Space Transportation System – HAER No. TX-116 – p. 46

- ↑ Spacelab: An International Success Story Forward by NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher

- ↑ Portree, David S. F. (2017-03-25). "Spaceflight History: NASA Johnson's Plan to PEP Up Shuttle/Spacelab (1981)". Spaceflight History. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ↑ Portree, David S. F. (2017-03-25). "Spaceflight History: NASA Johnson's Plan to PEP Up Shuttle/Spacelab (1981)". Spaceflight History. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph (2013-10-31). Dictionary of Space Technology. Routledge. ISBN 9781135944025.

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph (2013-10-31). Dictionary of Space Technology. Routledge. ISBN 9781135944025.

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph (2013-10-31). Dictionary of Space Technology. Routledge. ISBN 9781135944025.

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph (2013-10-31). Dictionary of Space Technology. Routledge. ISBN 9781135944025.

- ↑ David, Shayler; Burgess, Colin (2007-09-19). NASA's Scientist-Astronauts. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780387493879.

- ↑ [Spacelab mission typically supported multiple experiments, and the Spacelab-1 mission had experiments in the fields of space plasma physics, solar physics, atmosphere physics, astronomy, and Earth observation.<ReF>

- ↑

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph A. (2014-05-14). Human Spaceflight. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438108919.

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph A. (2014-05-14). Human Spaceflight. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438108919.

- ↑ NASA Historical Data Book. Scientific and Technical Information Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1988.

- ↑ NASA Historical Data Book. Scientific and Technical Information Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1988.

- ↑ "Spacelab pallet completes its long journey arriving at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum".

- 1 2 "ESA hands over a piece of space history".

- ↑

- ↑ https://www.space.com/23796-spacelab-space-shuttle-30-years-anniversary.html]

- ↑ Joseph A. Angelo (2007). Human Spaceflight. Facts on File. p. 272. ISBN 0-8160-5775-3.

- 1 2 3 "Spacelab Subsystems Igloo". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ↑ "Spacelab, Subsystems Igloo". National Air and Space Museum. 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 "Spacelab, Instrument Pointing System". 17 March 2016.

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2 Heusmann, H; Wolf, P (1985-10-31). "The Spacelab Instrument Pointing System (IPS) and its first flight". ESA Bulletin. 44: 75–79.

- ↑ KSC, Lynda Warnock:. "NASA – STS-35".

- ↑ Kent, et al. – Galactic structure from the Spacelab infrared telescope (1992).

- 1 2 "History of Infrared Astronomy". Archived from the original on 2016-12-21.

- ↑ NASA Historical Data Book. Scientific and Technical Information Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1988.

- ↑ NASA Historical Data Book. Scientific and Technical Information Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1988.

- ↑

- ↑ NASA Historical Data Book. Scientific and Technical Information Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1988.

- ↑

- ↑ David Michael Harland (2004). The Story of the Space Shuttle. Springer Praxis. p. 444. ISBN 978-1-85233-793-3.

- ↑ "Spacelab: Space Shuttle Flew Europe's First Space Module 30 Years Ago". Space.com. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ↑ "STS-2". NASA. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ↑ "STS-3". NASA. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Spacelab joined diverse scientists and disciplines on 28 Shuttle missions". NASA. 15 March 1999. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ↑ Tim Furniss; David Shayler; Michael Derek Shayler (2007). Manned Spaceflight Log 1961–2006. Springer Praxis. p. 829.

- ↑ "Germany and Piloted Space Missions". Fas.org. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ↑ "A new European science laboratory in Earth orbit" (PDF).

- ↑ "Cygnus Beyond Low-Earth Orbit – Logistics and Habitation in Cis-Lunar Space" (PDF).

- ↑ "Spacelab - eoPortal Directory - Satellite Missions".

- ↑ "chapter 1".

- Sources

- Lord, Douglas R. Spacelab An international success story, NASA-SP-487. NASA, January 1, 1987.

- SLP/2104-2: Spacelab Payload Accommodation Handbook

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spacelab. |

.jpg)

.jpg)