History of the United Arab Emirates

_p1.027_MAP_OF_OMAN_(retouched).jpg)

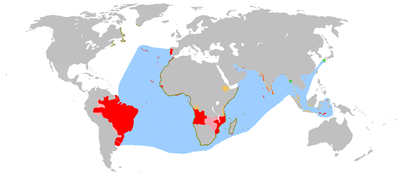

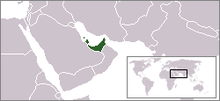

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a country on the Arabian Peninsula located on the southeastern coast of the Persian Gulf and the northwestern coast of the Gulf of Oman. The UAE consists of seven emirates and was founded on 2 December 1971 as a federation. Six of the seven emirates (Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain and Fujairah) combined on that date. The seventh, Ras al Khaimah, joined the federation on 10 February 1972. The seven sheikdoms were formerly known as the Trucial States, in reference to the treaty relations established with the British in the 19th Century.

Artifacts uncovered in the UAE show a history of human habitation and transmigration spanning back 125,000 years[1]. The area was previously home to the 'Magan people'[2] known to the Sumerians, who traded with both coastal towns and bronze miners and smelters from the interior. A rich history of trade with the Harappan culture of the Indus Valley is also evidenced by finds of jewellery and other items and there is also extensive early evidence of trade with Afghanistan[3] and Bactria[4] as well as the Levant.

Through the three defined Iron Ages and the subsequent Hellenistic Milieiha period, the area remained an important coastal trading entrepôt. As a result of the Ridda Wars, the area became Islamised in the 7th Century. Small trading ports developed alongside inland oases such as Liwa, Al Ain and Dhaid and tribal bedouin society co-existed with settled populations in the coastal areas.

A number of incursions and bloody battles took place along the coast when the Portuguese, under Albuquerque, invaded the area. Conflicts between the maritime communities of the Trucial Coast and the British led to the sacking of Ras Al Khaimah by British forces in 1809 and again in 1819, which resulted in the first of a number of British treaties with the Trucial Rulers in 1820. These treaties, including the Treaty of Perpetual Maritime Peace, signed in 1853, led to peace and prosperity along the coast and supported a lively trade in high quality natural pearls which lasted until the 1930s, when the pearl trade collapsed, leading to significant hardship among the coastal communities. A further treaty of 1892 devolved external relations to the British in return for protectorate status.

A British decision, taken in early 1968, to withdraw from its involvement in the Trucial States, led to the decision to found a Federation. This was agreed between two of the most influential Trucial Rulers, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi and Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum of Dubai. The two invited other Trucial Rulers to join the Federation. At one stage it seemed likely Bahrain and Qatar would also join the Union, but both eventually decided on independence.

Today, the UAE is a modern, oil exporting country with a highly diversified economy, with Dubai in particular developing into a global hub for tourism, retail, and finance,[5] home to the world's tallest building, and largest man-made seaport.

Prehistory

In 2011 primitive hand-axes, as well as several kinds of scrapers and perforators, were excavated at the Jebel Faya archaeological site in the United Arab Emirates. These tools resemble the types used by early modern humans in East Africa. Through the technique of thermoluminescence dating the artefacts were placed at 125,000 years old. This is the earliest evidence of modern humans found anywhere outside Africa and implies modern humans left Africa much earlier than previously thought.[1] The site of these discoveries has been preserved alongside finds of later cultures, including tombs and other finds from the Umm Al Nar, Wadi Suq and Islamic periods, at Sharjah's Mleiha Archaeological Centre.

During the glacial maximum period, 68000 to 8000 BCE, Eastern Arabia is thought to have been uninhabitable. Finds from the stone age Arabian Bifacial and Ubaid cultures (including stone arrow and axe heads as well as Ubaid pottery) show human habitation in the area from 5000 to 3100 BCE.

The Hafit period followed, named after extensive finds of burials of distinctive beehive shaped tombs in the mountainous area of Jebel Hafeet in Al Ain. Continued links to Mesopotamia are evidenced by finds of Jemdet Nasr pottery. The Hafit period spanned from 3200 to 2600 BCE.

Umm al-Nar and Wadi Suq Cultures

Umm al-Nar (also known as Umm an-Nar) was a bronze age culture variously defined by archaeologists as existing around 2600 to 2000 BCE in the area of the modern-day United Arab Emirates and Oman. The etymology derives from the island of the same name which lies adjacent to Abu Dhabi.[6] [7]The key site is well protected, but its location between a refinery and a sensitive military area means public access is currently restricted. The UAE authorities are working to improve public access to the site, and plan to make this part of the Abu Dhabi cultural locations. One element of the Umm al-Nar culture is circular tombs typically characterized by well fitted stones in the outer wall and multiple human remains within.[8]

The Umm al-Nar culture covers some six centuries (2600-2000 BCE), and includes further extensive evidence both of trade with the Sumerian and Akkadian kingdoms as well as with the Indus Valley. The increasing sophistication of the Umm al-Nar people included the domestication of animals.[9]

It was followed by the Wadi Suq Culture, which dominated the region from 2000 to 1300 BC. Key archaeological sites pointing to major trading cities extant during both periods exist on both the Western and Eastern coasts of the UAE and in Oman, including Dalma, Umm Al Nar, Sufouh, Ed Dur, Tell Abraq and Kalba. The burial sites at both Shimal and Seih Al Harf in Ras Al Khaimah show evidence of transitional Umm Al Nar to Wadi Suq burials.

The domestication of camels and other animals took place during the Wadi Suq era (2000-1300 BCE),[10] leading to increased inland settlement and the cultivation of diverse crops, including the date palm. Increasingly sophisticated metallurgy, pottery and stone carving led to more sophisticated weaponry and other implements even as evidence of strong trading links with the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia dwindled.

Iron Age

From 1200 BC to the advent of Islam in Eastern Arabia, through three distinctive iron ages (Iron age 1, 1200-1000 BC; Iron age II, 1000-600 BC and Iron age III 600-300 BC) and the Hellenistic Mleiha period (300 BC onward), the area was variously occupied by Archaemenid and other forces and saw the construction of fortified settlements and extensive husbandry thanks to the development of the falaj irrigation system (also called Qanat). Early finds of aflaj, particularly those around the desert city of Al Ain, have been cited as the earliest evidence of the construction of these waterways.[11] Important iron age centres in the UAE have rendered an unusual richness in finds to archaeologists, particularly the spectacular metallurgical centre of Saruq Al Hadid in what is today Dubai. Other important iron age settlements in the country include Al Thuqeibah, Bidaa bint Saud, Ed-Dur and Tell Abraq.

Advent of Islam

The arrival of envoys from Muhammad in 632 heralded the conversion of the region to Islam. After Muhammad's death, one of the major battles of the Ridda Wars was fought at Dibba, in present-day Fujairah. The defeat of the non-Muslims in this battle resulted in the triumph of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula.

In 637, Julfar (today Ras al-Khaimah) was used as a staging post for the conquest of Iran. Over many centuries, Julfar became a wealthy port and pearling centre from which dhows travelled throughout the Indian Ocean.

Trucial States

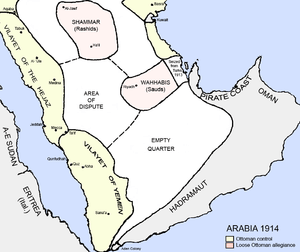

Ottoman attempts to expand their sphere of influence into the Indian Ocean failed[12] and it was Portuguese expansion into the Indian Ocean in the early 16th century following Vasco da Gama's route of exploration that resulted in the sacking of many coastal towns by the Portuguese. Following this conflict, the Al Qassimi, a seafaring tribe based on the Northern Peninsula and Lingeh on the Iranian coast, dominated the waterways of the Southern Gulf until the arrival of British ships, which came into conflict with the incumbents.[13]

Thereafter, the region was known to the British as the "Pirate Coast",[14] as Al Qasimi (to the British 'Joasmee') raiders based there harassed the shipping industry despite (or perhaps because of) British navy patrols in the area in the 18th and 19th centuries. A number of conflicts took place, notable between 1809-1819, when the Al Qasimi 'indulged in a carnival of maritime lawlessness to which even their own previous record presented no parallel' in the words of British historian John Lorimer.[15]

After years of incidents where British shipping had fallen foul of the aggressive Al Qasimi, with the first incidents taking place under the rule of Saqr bin Rashid Al Qasimi in 1797, an expeditionary force embarked for Ras Al Khaimah in 1809, the Persian Gulf campaign of 1809. This campaign led to the signing of a peace treaty between the British and Hussan Bin Rahmah, the Al Qasimi leader. This broke down in 1815. Lorimer contends that after the dissolution of the arrangement, the Al Qasimi "now indulged in a carnival of maritime lawlessness, to which even their own previous record presented no parallel". [16][17]

After an additional year of recurring attacks, at the end of 1818 Hassan bin Rahmah made conciliatory overtures to Bombay and was "sternly rejected." Naval resources commanded by the Al Qasimi during this period were estimated at around 60 large boats headquartered in Ras Al Khaimah, carrying from 80 to 300 men each, as well as 40 smaller vessels housed in other nearby ports.[18]

General Maritime Treaty

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In November 1819, the British embarked on an expedition against the Al Qasimi, led by Major General William Keir Grant, voyaging to Ras Al Khaimah with a platoon of 3,000 soldiers supported by a number of warships, including HMS Liverpool and Curlew. The British extended an offer to Said bin Sultan of Muscat in which he would be made ruler of the Pirate Coast if he agreed to assist the British in their expedition. Obligingly, he sent a force of 600 men and two ships.[19][20]

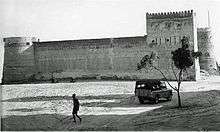

With the fall of Ras Al Khaimah and the final surrender of Dhayah Fort, the British established a garrison in Ras Al Khaimah of 800 sepoys and artillery, before visiting Jazirat Al Hamra, which was found to be deserted. They went on to destroy the fortifications and larger vessels of Umm Al Qawain, Ajman, Fasht, Sharjah, Abu Hail, and Dubai. Ten vessels that had taken shelter in Bahrain were also destroyed.[21]

As a consequence of the campaign, the next year, a peace treaty was signed with all the sheikhs of the coastal communities, the General Maritime Treaty of 1820.

The 1820 treaty was followed by the 1847 'Engagement to Prohibit Exportation of Slaves From Africa on board of Vessels Belonging to Bahrain and to the Trucial States and the Allow Right of Search of April-May 1847'.[22] By this time, some of the smaller Sheikhdoms had been subsumed by their larger neighbours and signatories were Sheikh Sultan bin Saqr of Ras Al Khaimah; Sheikh Maktoum of Dubai; Sheikh Abdulaziz of Ajman, Sheikh Abdullah bin Rashid of Umm Al Quwain and Sheikh Saeed bin Tahnoun of Abu Dhabi.

The treaty only granted protection to British vessels and did not prevent coastal wars between tribes. As a result, raids continued intermittently until 1835, when the sheikhs agreed not to engage in hostilities at sea for a period of one year. The truce was renewed every year until 1853.

Perpetual Maritime Truce

In 1853, the Perpetual Maritime Truce of 4 May 1853 prohibited any act of aggression at sea and was signed by Abdulla bin Rashid of Umm Al Quwain; Hamed bin Rashid of Ajman; Saeed bin Butti of Dubai; Saeed bin Tahnoun ('Chief of the Beniyas') and Sultan bin Saqr ('Chief of the Joasmees').[23] A further engagement for the suppression of the slave trade was signed in 1856 and then in 1864, the 'Additional Article to the Maritime Truce Providing for the Protection of the Telegraph Line and Stations, Dated 1864'. An agreement regarding the treatment of absconding debtors followed in June 1879.[24][25]

Exclusive Agreement

Signed in 1892, the 'Exclusive Agreement' bound the Rulers not to enter into 'any agreement or correspondence with any Power other than the British Government' and that without British assent, they would not 'consent to the residence within my territory of the agent of any other government' and that they would not 'cede, sell, mortgage or otherwise give for occupation any part of my territory, save to the British Government.[26][27] In return, the British promised to protect the Trucial Coast from all aggression by sea and to help in case of land attack.[28]

Recognition of emirates

Significantly, the treaties with the British were maritime in nature and the Trucial Rulers were free to manage their internal affairs, although they often brought the British (and their naval firepower) to bear on their frequent disputes. This was particularly the case where disputes involved indebtedness to British and Indian nationals.

During the late 19th and early 20th-century a number of changes occurred to the status of various emirates, for instance emirates such as Rams and Zyah (now part of Ras Al Khaimah) were signatories to the original 1819 treaty but not recognised by the British as trucial states in their own right, while the emirate of Fujairah, today one of the seven emirates that comprise the United Arab Emirates, was not recognised as a Trucial State until 1952. Kalba, recognised as a Trucial State by the British in 1936 is today part of the emirate of Sharjah.[29]

The rise and fall of the pearling industry

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the pearling industry thrived in the relative calm at sea, providing both income and employment to the people of the Persian Gulf. in 1907, some 4,500 pearling boats were operating from Gulf ports in an industry employing over 74,000 men.[30]

The Japanese cultured pearl, first a wonder shown at expos and other fairs[31], started to be produced in commercial quantities in the late 1920s. The influx of inexpensive, high quality pearls to world markets took place alongside the economic blight of the Great Depression. The result on the Gulf's pearl markets was devastating. In 1929, 60 of Dubai's pearling boats (in 1907 there were 335 boats operating out of the port) stayed in port throughout the season[32].

The complex system of financing that underpinned the pearling industry, the relationship between owners, pearl merchants, nakhudas (captains) and divers and pullers fell apart and left an increasingly large number of working men in the town facing destitution.[33]

In the 1930s, a record number of slaves approached the British Agent seeking manumission, a reflection of the parlous state of the pearling fleet and its owners.[34]

The beginning of the oil era

In the 1930s, the first oil company teams carried out preliminary surveys. An onshore concession was granted to Petroleum Development (Trucial Coast) in 1939, and an offshore concession to D'Arcy Exploration Ltd in 1952.[35] Exploration concessions were limited to British companies only following the conclusion of agreements with the Trucial Sheikhs and British government. Management of the Trucial Coast moved from the British Government in Bombay to the Foreign Office in London in 1947, with Indian independence. The Political Resident in the Gulf headed the small team responsible for liaison with the Trucial Sheikhs and was based in Bushire until 1946, when his office was moved to Bahrain. Day to day management of affairs was carried out by the 'Native Agent', a post established with the 1820 treaty and abolished in 1949. This agent was bolstered by a British Political Officer based in Sharjah, from 1937 onwards. [36]

Oil was discovered under an old pearling bed in the Persian Gulf, Umm Shaif, in 1958, and in the desert at Murban in 1960. The first cargo of crude was exported from Jabel Dhanna in Abu Dhabi in 1962. As oil revenues increased, the ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, undertook a massive construction program, building schools, housing, hospitals and roads. When Dubai's oil exports commenced in 1969, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai, was also able to use oil revenues to improve his people's quality of life.[37]

Buraimi dispute

In 1952 a group of some 80 Saudi Arabian guards, 40 of whom were armed, led by the Saudi Emir of Ras Tanura, Turki Abdullah al Otaishan, crossed Abu Dhabi territory and occupied Hamasa, one of three Omani villages in the Oasis, claiming it as part of the eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. The Sulṭan of Muscat and Imam of Oman gathered their forces to expel the Saudis but were persuaded by the British Government to exercise restraint pending attempts to settle the dispute by arbitration. A British military build-up took place, leading to the implentation of a standstill agreement and the referral of the dispute to an international arbitration tribunal. In 1955 arbitration proceedings began in Geneva only to collapse when the British arbitrator, Sir Reader Bullard, objected to Saudi Arabian attempts to influence the tribunal and withdrew. A few weeks later, the Saudi party was forcibly ejected from Hamasa by the Trucial Oman Levies.[38]

The dispute was finally settled in 1974 by an agreement, known as the Treaty of Jeddah, between Sheikh Zayed (then President of the UAE) and King Faisal of Saudi Arabia.[39]

Sheikh Zayed and the Union

In the early 1960s, oil was discovered in Abu Dhabi, an event that led to quick unification calls made by UAE sheikdoms. Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan became ruler of Abu Dhabi in 1966, and the British started losing their oil investments and contracts to U.S. oil companies.[40]

The British had earlier started a development office that helped in some small developments in the emirates. The sheikhs of the emirates then decided to form a council to coordinate matters between them and took over the development office. They formed the Trucial States Council,[41] and appointed Adi Bitar, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum's legal advisor, as Secretary General and Legal Advisor to the Council. This council was terminated once the United Arab Emirates was formed.[42]

Independence

By 1966, the British government had come to the conclusion that it could no longer afford to govern what is now the United Arab Emirates.[43] Much deliberation took place in the British parliament, with a number of MPs arguing that the Royal Navy would not be able to defend the Trucial Sheikhdoms. Denis Healey, who, at the time, was the UK Secretary of State for Defence, reported that the British Armed Forces were severely overextended, and in some respects, dangerously under-equipped to defend the Sheikhdoms.[44] On 16 January 1968, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced the decision to end the treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Sheikhdoms which had been, together with Bahrain and Qatar, under British protection.[45] The British decision to withdraw was reaffirmed in March 1971 by Prime Minister Edward Heath.[46]

Days after the announcement Sheikh Zayed, fearing vulnerability, tried to persuade the British to honour the protection treaties by offering to pay in full the costs of keeping the British Armed Forces in the Emirates. The British Labour government rebuffed the offer.[47][48]

Federation of Emirates

After Labour MP Goronwy Roberts informed Sheikh Zayed of the news of British withdrawal, the nine Persian Gulf sheikhdoms attempted to form a federation of Arab emirates.[48] The federation was first proposed in February 1968 when the rulers of Abu Dhabi and Dubai met in the desert location of Argoub El Sedirah and agreed on the principle of Union.[49] They announced their intention to form a coalition, extending an invitation to other Persian Gulf states to join. Later that month, in a summit meeting attended by the rulers of Bahrain, Qatar and the Trucial Coast, the government of Qatar proposed the formation of a federation of Arab Emirates to be governed by a higher council composing of nine rulers. This proposal was accepted and a declaration of union was approved.[50] There were, however, several disagreements between the rulers on matters such as the location of the capital, the drafting of the constitution and the distribution of ministries.[50]

Further political issues surfaced as a result of Bahrain attempting to impose a leading role in the nine-state union, as well as the emergence of a number of differences between the rulers of the Trucial Coast, Bahrain and Qatar, the latter two being in a long-running dispute over the Hawar Islands. While Dubai's ruler, Sheikh Rashid, had a strong connection to the Qatari ruling family, including the royal intermarriage of his daughter with the son of the Qatari emir,[51] the relationship between Abu Dhabi and Dubai (also cemented by intermarriage, Rashid's wife was a member of Abu Dhabi's ruling family[49]) was to endure the break-up of the talks with both Bahrain and Qatar. Overall, there were only four meetings between the nine rulers.[51] The last such meeting, which took place in Abu Dhabi, saw Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan elected as the first president of the federation. There were stalemates on numerous issues during the meeting, including the position of vice-president, the defence of the federation, and whether a constitution was required.[51]

Shortly after the meeting, the Political Agent in Abu Dhabi revealed the British government's interests in the outcome of the session, prompting Qatar to withdraw from the federation apparently over what it perceived as foreign interference in internal affairs[52]. The nine-emirate federation was consequently disbanded despite efforts by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Britain to reinvigorate discussions.[53] Bahrain became independent in August 1971, and Qatar in September 1971.

1971–1972

When the British-Trucial Sheikhdoms treaty expired on December 1, 1971, the Trucial States became fully independent sheikhdoms.[48][54] Four more of the Trucial states (Ajman, Sharjah, Umm Al Quwain and Fujairah), had decided to join Abu Dhabi and Dubai in signing the UAE's founding treaty, with a draft constitution in place drafted in record time to meet the December 2, 1971 deadline.[55] On that date, at the Dubai Guesthouse (now known as Union House), the emirates agreed to enter into a union to be called the United Arab Emirates. Ras al-Khaimah joined later, following Iran's swift annexation of the Tunbs islands, in early 1972.[56][57]

The move to form a union took place at a time of unprecedented instability in the region, with a border dispute killing 22 in Kalba and a coup in Sharjah in January 1972. The then emir of Qatar was deposed by his cousin in February 1972.

1973–2003

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, the UAE was identified as a major financial centre used by Al-Qaeda in transferring money to the hijackers. The nation immediately cooperated with the United States, freezing accounts tied to suspected terrorists and strongly clamping down on money laundering.[58]

The country had already signed a military defence agreement with the United States in 1994 and one with France in 1995.

The UAE supports military operations from the United States and other coalition nations engaged in the invasion of Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) as well as operations supporting the Global War on Terrorism for the Horn of Africa at Al Dhafra Air Base, located outside of Abu Dhabi. The air base also supported Allied operations during the 1991 Persian Gulf War and Operation Northern Watch.

2004–2008

On 2 November 2004, the UAE's first president, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, died. His eldest son, Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, succeeded him as ruler of Abu Dhabi. In accordance with the constitution, the UAE's Supreme Council of Rulers elected Khalifa as president. Sheikh Mohammad bin Zayed Al Nahyan succeeded Khalifa as Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi.[59] In January 2006, Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the prime minister of the UAE and the ruler of Dubai, died, and Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum assumed both roles.

In March 2006, the United States forced the state-owned Dubai Ports World to relinquish control of terminals at six major American ports. Critics of the ports deal feared an increased risk of terrorist attack, saying the UAE had been home to two of the 9/11 hijackers.[60]

In December 2006, the UAE prepared for its first election to determine half the members of UAE's Federal National Council from 450 candidates. However, only 7000 Emirati citizens, less than 1% of the Emirati population, were given the right to vote in the election. The exact manner of selection was opaque. Notably, women were included in the electorate.[61]

2011–Present

In August 2011, the Middle East saw a number of pro-democratic uprisings, popularly known as the Arab Spring. The UAE saw comparatively little unrest, but did face one high-profile case in which five pro-democracy activists were arrested on charges of insulting the president, Sheikh Khalifa, the vice president, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, and the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi (and presumed successor to Sheikh Khalifa), Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.[62] The trial of the UAE Five attracted international publicity and protest from a number of human rights groups,[63] including Amnesty International, which named the five men prisoners of conscience.[62] The defendants were convicted and given two- to three-year prison sentences on 27 November 2011. However, all five were pardoned without comment by Sheikh Khalifa the following day.[64]

See also

References

- 1 2 http://earthsky.org/human-world/new-timeline-for-first-early-human-exodus-out-of-africa

- ↑ "Digging in the Land of Magan - Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ Heritage, Sharjah Directorate of Antiquities &. "Tell Abraq – Sharjah Directorate of Antiquities & Heritage". sharjaharchaeology.com. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ United Arab Emirates : a new perspective. Abed, Ibrahim., Hellyer, Peter. London: Trident Press. 2001. ISBN 978-1900724470. OCLC 47140175.

- ↑ http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/index.php

- ↑ UAE History: 20,000 - 2,000 years ago - UAEinteract Archived 2013-06-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "UNESCO - Tentative Lists". Settlement and Cementery of Umm an-Nar Island. UNESCO. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ The Archaeology of Ras al-Khaimah Archived 2009-03-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Uerpmann, Margarethe (2001). "Remarks on the animal economy of Tell Abraq (Emirates of Sharjah and Umm al-Qaywayn, UAE)". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 31: 227–233. JSTOR 41223685.

- ↑ Almathen, Faisal; Charruau, Pauline; Mohandesan, Elmira; Mwacharo, Joram M.; Orozco-terWengel, Pablo; Pitt, Daniel; Abdussamad, Abdussamad M.; Uerpmann, Margarethe; Uerpmann, Hans-Peter (2016-06-14). "Ancient and modern DNA reveal dynamics of domestication and cross-continental dispersal of the dromedary". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (24): 6707–6712. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519508113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4914195. PMID 27162355.

- ↑ TIKRITI, WALID YASIN AL (2002). "The south-east Arabian origin of the falaj system". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 32: 117–138. JSTOR 41223728.

- ↑ "Ottoman Empire - History of Ottoman Empire | Encyclopedia.com: Dictionary of Contemporary World History". Encyclopedia.com. 1923-10-29. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ 1939-, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī, Ruler of Shāriqah, (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0709921066. OCLC 12583612.

- ↑ Belgrave, Sir Charles (1966) The Pirate Coast, London: G. Bell and Sons

- ↑ Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 653.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [653] (796/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2014. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [654] (797/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 4 August 2015. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [656] (799/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 26 September 2018. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [659] (802/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ Moorehead, John (1977). In Defiance of The Elements: A Personal View of Qatar. Quartet Books. p. 23. ISBN 9780704321496.

- ↑ Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 669.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 288. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 286. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 211. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ Perpetual Maritime Truce of 4 May 1853

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 293. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ Exclusive Agreement, signed between March 5 and March 8, 1892

- ↑ Tore Kjeilen (2007-04-04). "Trucial States". Looklex.com. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 2220.

- ↑ "MIKIMOTO History | About MIKIMOTO | MIKIMOTO". MIKIMOTO | Jewelry, Pearl, Diamond. Retrieved 2018-09-24.

- ↑ Wilson, Graeme (1999). Father of Dubai. Media Prima. pp. 40–41.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 250. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 251. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ Morton, Michael Quentin (July 2016). "The Search for Offshore Oil Abu Dhabi". AAPG Explorer. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ 1976-, Alhammadi, Muna M.,. Britain and the administration of the Trucial States 1947-1965. Markaz al-Imārāt lil-Dirāsāt wa-al-Buḥūth al-Istirātījīyah. Abu Dhabi. pp. 34–38. ISBN 9789948146384. OCLC 884280680.

- ↑ "Middle East | Country profiles | Country profile: United Arab Emirates". BBC News. 2009-03-11. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ Donald., Hawley, (1970). The Trucial States. London,: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0049530058. OCLC 152680.

- ↑ Quentin., Morton, Michael (2013). Buraimi : the Struggle for Power, Influence and Oil in Arabia. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1299908499. OCLC 858974407.

- ↑ "United Arab Emirates - Oil and Natural Gas". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ "Al Khaleej News Paper". Archived from the original on 2008-08-03.

- ↑ "Trucial States Council until 1971 (United Arab Emirates)". Fotw.net. Archived from the original on 2011-04-29. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 336. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ "Sun sets on British Empire as UAE raises its flag". The National. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. p. 337. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ Morton, Michael Quentin (February 2016). Keepers of the Golden Shore: A History of the United Arab Emirates (1st ed.). London: Reaktion Books. pp. 178–199. ISBN 978-1780235806. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ Jonathan Gornall. "Sun sets on British Empire as UAE raises its flag - The National". Thenational.ae. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- 1 2 3 "History the United Arab Emirates UAE". TEN Guide. 1972-02-11. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- 1 2 Maktoum, Mohammed (2012). Spirit of the Union. UAE: Motivate. pp. 30–38. ISBN 9781860633300.

- 1 2 Zahlan, Rosemarie Said (1979). The creation of Qatar (print ed.). Barnes & Noble Books. p. 104. ISBN 978-0064979658.

- 1 2 3 R.S. Zahlan (1979), p. 105

- ↑ 1941-, Heard-Bey, Frauke, (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. pp. 352–3. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- ↑ R.S. Zahlan (1979), p. 106

- ↑ "Bahrain – INDEPENDENCE". Country-data.com. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ "United Arab Emirates: History, Geography, Government, and Culture". Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ Smith, Simon C. (2004). Britain's Revival and Fall in the Gulf: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the Trucial States, 1950–71. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33192-0. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ "Trucial Oman or Trucial States – Origin of Trucial Oman or Trucial States". Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ Cloud, David S. (2006-02-23). "U.S. Sees Emirates as Both Ally and, Since 9/11, a Foe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-01-20.

- ↑ "Veteran Gulf ruler Zayed dies". BBC News. 2004-11-02. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ "United Arab Emirates profile". BBC News. 2013-10-26.

- ↑ Wheeler, Julia (15 December 2006). "UAE prepares for first elections". Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- 1 2 "UAE: End Trial of Activists Charged with Insulting Officials". Amnesty International. 17 July 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ "Five jailed UAE activists 'receive presidential pardon'". BBC News. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ "UAE pardons jailed activists". Al Jazeera. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of the United Arab Emirates. |