New Albion

New Albion, also known as Nova Albion, was the name of the continental area in the northwesternmost part of Mexico (northwestern Alta California) claimed by Sir Francis Drake for England in 1579. This claim on the Pacific coast, which became the justification for English charters across America to the Atlantic coast, soon influenced further national expansion projects on the continent. Today, it is known as Point Reyes, California, a marine environment which is the setting of several small towns, ranches, and the Point Reyes National Seashore.

In the late sixteenth century, Drake developed a plan to use investors' support so he could sail into the Pacific to plunder Spanish settlements and ships and search for the hypothetical Strait of Anián which was thought to exist somewhere along the present-day Northern California or Oregon coasts, connecting the Pacific and Atlantic. Drake embarked on the journey in November 1577, and after successfully raiding Spanish towns and ships along their eastern Pacific coast colonies, he sailed north to seek a shortcut back to England via the Strait of Anián. Upon not finding it and to avoid reprisal by Spaniards he might encounter by sailing back through their territory, Drake decided that circumnavigation would be required to return to England. So, he sought safe harbor to prepare his ship, the Golden Hind, for the long journey.

On June 17 of 1579, Drake and his crew landed on the Pacific coast at what is now Point Reyes in Northern California. He had very friendly relations with the Coast Miwok people who inhabited the area near his landing. Living in thriving village communities, multitudes of Coast Miwok visited the English encampment daily, and Drake reciprocated with a visits by crossing a nearby ridge into an inland valley. Naming the area Nova Albion, or New Albion, he claimed sovereignty of the area for Elizabeth I of England, an act which would have significant long-term historical consequences. After effecting repairs while careening his ship, Drake set sail a few weeks later on July 23, 1579. Leaving behind no permanent presence, he circumnavigated the globe, finally returning to England in September 1580.

Over the years, numerous speculative sites along the North American Pacific coast were investigated as the area of Drake's New Albion claim. Through the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, various cartographers and mariners identified the area near Point Reyes as Drake's likely landing place. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, definitive evidence was gathered, particularly regarding Drake's contact with the Coast Miwok people and porcelain shards which were established to be remnants of Drake's cargo. In October 2012, all of this culminated in the United States Department of the Interior—using a National Historic Landmark designation—formally recognizing Drake's landing being at Point Reyes, California.

Background

In the late 1500's, a type of cold war existed between England and Spain—one which involved religious differences, economic pressure, and emerging English navigational and colonization desires.[1] As part of this, Drake developed a plan to plunder Spanish colonial settlements on the Pacific Coast of the New World.[2] Gathering several investors,[3] and likely with the backing of Queen Elizabeth—[4] which may have been in the form of a secret commission as a privateer—[5][6] Drake embarked upon the voyage on November 15, 1577.[7] He knew that while his raids would anger King Philip of Spain, Queen Elizabeth would stand by him.[8]

After successfully taking much treasure from the Spanish by raiding towns and ships along their eastern Pacific coast colonies, Drake sailed north to seek a shortcut back to England via the hypothetical Strait of Anián, a supposedly navigable shortcut connecting the Pacific and Atlantic. It was incorrectly speculated to exist at about 40 degrees north.[9] Not finding it, he sought safe harbor to ready his ship, Golden Hind, before attempting a circumnavigation of the globe to return home. Up to then, the western coast of North America had been partially explored in 1542 by Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, who sailed for the Spanish.[10] Needing safe haven from further conflict with Spain, Drake sought safety by heading north and west of Spanish presence, well beyond where Cabrillo had asserted Spanish claim.[11]

The ship briefly made first landfall at South Cove, Cape Arago, just south of Coos Bay, Oregon.[13] From there, he sailed south and on June 17, 1579, Drake and his crew landed on the Pacific coast of what is now Northern California. He claimed the area for Queen Elizabeth I as Nova Albion or New Albion.[14] Drake chose this particular name for two reasons: first, the white banks and cliffs which he saw were similar to those found on the English coast and, second, because Albion was an archaic name by which the island of Great Britain was known.[15] To document and assert his claim, Drake had an engraved plate of brass, one which contained a sixpence bearing Elizabeth's image, attached to a large post. Giving details of Drake's visit, it claimed sovereignty for Elizabeth and every successive English monarch.[16]

The crew worked for several weeks as they careened their ship, Golden Hind, preparing it for the circumnavigating voyage ahead. Ashore, the men erected a fort and tents as the ship's hull was cleaned and repaired.[17] Drake explored the surrounding land by foot, and when his ship was ready for the return voyage, he and the crew left New Albion on July 23.[18] Sailing west across the Pacific, they returned to England in September 1580.[19]

As a result of his successful deeds against the Spanish, Drake was admired and celebrated by many in England. Not only were his investors and the Queen richly rewarded, Drake was also allowed to keep £24,000 of the purloined treasure for himself and his crew.[20] Drake quickly became a favorite at the Queens's court and was knighted by the French Ambassador on her behalf.[21] According to John Stow, Drake's "name and fame became admirable in all places, the people swarming daily in the streets to behold him, vowing hatred of all that durst mislike him."[22]

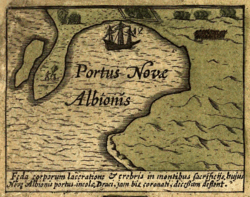

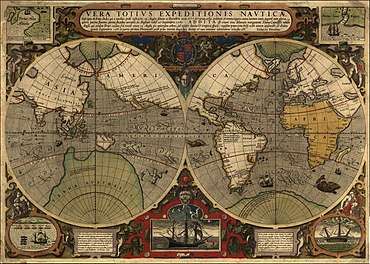

Initially, details of Drake's voyage were suppressed, and Drake's sailors were pledged not to disclose their route under threat of death.[23][24] When Drake returned, he handed over his log and a large map to the Queen.[25] While the other items disappeared, the map known as the Queen's Map, remained on limited view for a number of years.[26] Finally, it too was lost when Whitehall Palace burned in 1698.[27] Samuel Purchas, who had seen the map in 1625 at Whitehall Palace, was able to describe it in such detail that his description of the map makes it possible to identify various derivatives.[28] One of these derivatives is Vera Totius Expeditionis Navticae, c. 1590 by Jodocus Hondas, who incorporated features from the Queen's Map.[29] This map shows Drake's journey and includes an inset of the harbor at Nova Albion.[30] In 1579, an official account of Drake's circumnavigating voyage by Richard Hakluyt was published. Another account of the voyage, The World Encompassed, which is based on the notes of his chaplain Francis Fletcher, included many details of New Albion and was published in 1628 by Drake's nephew and namesake, Sir Francis Drake, 1st Baronet. It is the most extensive account of Drake's voyage.[31]

Although the location of Drake's New Albion differs among maps, after Elizabeth's death, they began to depict the area of North America above Mexico as Nova Albion. Drake's claim of land on the Pacific coast for England became the legal basis for subsequent colonial charters issued by English monarchs that purported to grant lands from sea to sea, the area from the Atlantic where English colonies were first settled and to the Pacific. Along with Martin Frobisher's claims in Greenland and Baffin Island and Humphrey Gilbert's 1583 claim of Newfoundland, New Albion was one of the earliest English territorial claims in the New World.[32] These claims were eventually followed by settlement of the Roanoke Colony in 1584, and Jamestown, Virginia in 1607.[33]

Historical impact

The New Albion claim had far-reaching historical consequences. Because Drake attempted no long-term presence, the English made no immediate follow up to the claim.[34] And since all of their subsequent expeditions along the North American Pacific Coast were infrequent and irregular,[35][36] Nova Albion was primarily a geographical designation—a new distinctive name on the world map. Ultimately, this designation was of significance as it proclaimed England's ability and presumed right to pursue its own empire in America.[37] Consequently, Drake's New Albion claim was a forward-thinking, considered component of a new national expansion policy,[38] one of several of his exploits which both determined Elizabeth's policy for the duration of her reign and indirectly impacted England's continuing historical future.[39] The New Albion claim was the first indication of English goals broader than simple reprisal against Spain which then influenced similar national expansion projects by others such as Humphrey Gilbert and Walter Raleigh.[40] As a rejection of territorial claims based on papal authority, the New Albion claim asserted Elizabeth's notion of territorial claim by occupation,[41] which eventually promoted the colonial idea of New Albion as “the backside of Virginia,”[42] the expression of England's presumed legal status of sea-to-sea colonial entitlement.

Site recognition and identification

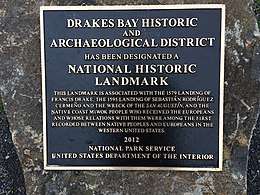

Official recognition: United States National Historic Landmark

The site of Drake's landing, officially recognized by the U.S. Department of the Interior and other agencies, is Drake's Cove, located in Drakes Estero which runs northerly off Drakes Bay. The bay is in Marin County, California, near Point Reyes, just north of the Golden Gate. 38°02′02″N 122°56′28″W / 38.034°N 122.941°W.[43] On October 16, 2012, Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar signed the nomination and on October 17, 2012, the Drakes Bay Historic and Archaeological District was formally announced as a new National Historic Landmark.[44] No Drake anchorage has endured so much scrutiny or seen the amount of field study and research as has this location.[45]

This district, a nationally significant distinction, provides material evidence of one of the earliest instances of interaction between native people and European explorers on the west coast of what is now the United States of America. This distinction is based on the two historical encounters, Sir Francis Drake's 1579 California landfall and the 1595 Manila Galleon shipwreck, ‘'San Agustin, which was commanded by Sebastian Rodriguez Cermeño.[46]

Seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century identification

Starting in the seventeenth century, maps identify Drakes Bay as Drake's landing site.[47] In 1793, George Vancouver studied the site, and concluded it was in Drakes Bay.[48] Professor George Davidson, of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, after a careful study of the narrative and the coast identified the harbour entered by Drake with Drake's Bay, under Point Reyes, about thirty miles (50 km) north of San Francisco. "Drake's Bay," he reported in 1886, "is a capital harbor in northwest winds, such as Drake encountered. It is easily entered, sheltered by high lands, and a vessel may anchor in three fathoms, close under the shore in good holding ground."[49] Davidson published further support for the Drakes Bay location in 1890[50] and 1908.[51]

Twentieth-century identification

Robert F. Heizer, one of the 20th century's preeminent archeologists, spent most of his career researching prehistoric and historic Native American peoples of the western United States, particularly in California and Nevada.[52] In 1947, following up on work by Professor A. L. Kroeber and William W. Elemendorf, he analyzed the ethnographic reports of Drake's stay at New Albion. Heizer states that "Drake must have landed in territory occupied by the Coast Miwok-speaking natives." In his full analysis, Heizer concludes, "in June 1579, then, Drake probably landed in what is now known as Drake's Bay."[53]

Since 1949, the theory that Drake landed at Drakes Bay has been advocated by the Drake Navigators Guild in California, and by former president Captain Adolph S. Oko, Jr., former honorary chairman Chester W. Nimitz, and former president Raymond Aker. Oko wrote, "Many other correlative facts have been ... found true to the Drake's Cove site as part of the total body of evidence. The weight of evidence truly establishes Drake's Cove as the nodal point of Nova Albion."[54] Nimitz stated that he did "not doubt that in time the public will come to recognize the importance and value of this long-lost site, and will rank it with other National Historic Sites such as Roanoke, Jamestown, and Plymouth."[55]

Aker conducted detailed studies reconstructing Drake's circumnavigation voyage. Advocates of this theory cite the fact that the official published account placed the colony at 38 degrees north. The geography of Drake's Cove, which lies along the coast of Marin County, has often been suggested as being similar to the cove described by Drake, including the white cliffs that look like the south coast of England and the specific configuration of the Cove. Responding to questions about the geographical fit of the cove, Aker maintained that criticisms—those based on the inconsistent configuration of the sandbars in the cove—were unfounded. He maintained the configuration of the sandbars in the cove was cyclic over the decades. Accordingly, Aker effectively answered the questions when he predicted that a spit of land that disappeared in 1956—one which closely resembles one on the Hondius map—would reappear. Aker's assertions were confirmed when the spit formed again in 2001.[56]

Nearly one hundred pieces of sixteenth-century Chinese porcelains, have been found in the vicinity of the Drake's Cove site which "must fairly be attributed to Francis Drake's Golden Hind visit of 1579."[57] These ceramic samples, found at Point Reyes, are the earliest datable archaeological specimens of Chinese porcelains transported across the Pacific in Manilla galleons.[58] The artifacts were found by four different agencies beginning with the University of California, the Drake Navigators Guild, then the Santa Rosa Junior College, and finally San Francisco State College.[59][60] These porcelain shards were abandoned by Drake at Point Reyes after he took porcelain dishes from a Spanish treasure ship during his venture into the Pacific.[61]

The porcelains were first identified by Clarence Shangraw of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco and later by archaeologist Edward Von der Porten. These researchers specifically distinguished the Drake porcelains, which were found in middens associated with the Coast Miwok, from those of Cermeño, which washed up on the Point Reyes seashore.[62] They did so using such criteria as design, style, quality, and surface wear. The Drake porcelains have clean breaks and show no abrasion from the corrosive action of being tumbled in the surf. In contrast, the Cermeño shards display surf-tumbling, design change, and differences in style and quality—all which suggests two separate cargoes.[63]

Twenty-first-century identification

Examining the Drake landing site from a nautical perspective and including recent analyses, Sir Simon Cassels, Second Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Personnel, Royal Navy, concluded that "the weight of evidence... bears heavily on only one and the same site for careening the Golden Hind: the estuary within what for more than 100 years has been named Drakes Bay."[64]

Providing further research, Dr. Marco Meniketti of San Jose State University tested ceramics from shipwrecks in Mexico, California, and Oregon, as well as porcelains linked to Drake found near Point Reyes. Using varied shipwreck sources to provide strong controls to the research, Meniketti's findings confirm the Cermeño porcelains and the Drake ceramics are from two different ships. He states that these two cargoes can be distinguished based on differences in their key elements and believes these differences may represent changes in glaze chemistry, clay sources, or unique inclusions or tempering.[65] All those porcelain shards that washed onto shore must be attributed to Cermeño, and those with clean breaks and no water wear must be attributed to Drake.[66]

Author Dr. John Sugden reviewed the proposed Drake landing sites, observing, "No aspect of Drake's career has suffered more false leads than the site of Nova Albion." Sugden concludes that "the evidence overwhelmingly favours Drake's Estero in Drakes Bay" and that "it is high time the United States register of National Historic Landmarks officially recognized Drake's Estero as the Elizabethan anchorage."[67]

Coast Miwok

Before any Europeans came to California, the Coast Miwok people inhabited what is now called Marin County and southern Sonoma County, CA. The Coast Miwok recognize their first contact with Europeans as with Sir Francis Drake in 1579.[68] Heizer described the people as "... the most remarkable objects of interest with which he came in contact.[69] Living in village communities ranging from 75 to several hundred people, the Coast Miwok developed a thriving economy based on hunting, fishing, and gathering. Typically, a village was located in a sheltered place near fresh water and food sources.[70] While once numbering up to 5,000, the Coast Miwok population dwindled to as low as 13 after encroachment of non-indigenous people.[71]

Prior to European contact, California's prehistoric population in which the Coast Miwok lived, exhibited no fewer than sixty-four distinct languages. This linguistic variety was more than all of Europe.[72] Fletcher recorded five specific Coast Miwok words, the earliest documentation of their language: Hioh, Gnaah, Huchee kecharo, Nacharo mu, and Cheepe.[73] These words, Heizer states, are unquestionably of Coast Miwok derivation and provide linguistic proof of Drake's contact with the Coast Miwok,[74] Drake's landing at present-day Point Reyes was the first contact the Coast Miwok had with Europeans,[75] and multitudes of the people visited Drake's encampment daily.[76] Early when Drake and his crew encountered the Coast Miwok, they observed as the Miwok wailed and scratched themselves.[77] Drake misinterpreted this response as an act of worship and concluded that the Indians believed them to be gods. This response was actually one of Miwok mourning customs. Most likely the Indians regarded the English visitors as relatives who had returned from the dead.[78]

In a gesture of extraordinary significance, one day a large assembly of Coast Miwok descended on the encampment to honor Drake by placing chains around his neck, a scepter in his hand, and a crown of feathers on his head as if he were being proclaimed king.[79] It was upon this uncertain, seemingly voluntary surrender of sovereignty by its owners that England based its presumed legal authority to the territory.[80][81] The relations between the Coast Miwok and their visitors were peaceful and friendly, and the Miwok seemed to exhibit distress when the Golden Hind sailed away.[82] Fletcher described their village structures as round subterranean buildings which came together at the top like spires on a steeple.[83] Kule Loklo, meaning Bear Valley, is a recreated village at Point Reyes National Seashore in the area where Coast Miwok lived. The village, built from traditional material, was constructed using Coast Miwok rituals and protocols[84] and is similar to those Coast Miwok villages encountered by Drake.[85]

Coast Miwok were such skilled basket makers that even their feathered baskets were made to be watertight.[86] Of particular importance to the identification of New Albion are their unique baskets, fully feathered baskets, ones matted with feathers. They were described by Drake's chaplain as shaped like a deep bowl, covered with a matted down of colored feathers.[87] Such baskets were made only by the Coast Miwok, Pomo, Lake Miwok, Patwin, and Wappo peoples who were all concentrated near Drake's landing site.[88][89] These rare, valued feathered baskets were sacrificial, as they were burned to honor the deceased owner,[90] and most fully feathered Coast Miwok baskets that exist today are found in Saint Petersburg, Russia.[91][92] This 1579 type of fully feathered basket was still similarly manufactured and used by the Coast Miwok into the 20th century.[93]

Speculation of a colony

There is a discrepancy of at least 20 men regarding the number of crew that Drake commanded prior to his stay in Northern California and when he reached the Moluccas, an archipelago within the Banda Sea, Indonesia. Released Spanish prisoners stated that off the coast of Central America, the ship's company was about 80 men. Francis Drake's nephew and crewmember, John Drake, claimed the number totaled 60 when the ship was at Ternate in the Moluccas. On Vesuvius Reef, The World Encompassed puts the number at 58.[94] The reasons for the discrepancy are unknown.

This has led to speculation that Drake left behind men to form a colony; however, that is unlikely, and any embryo colony notions are based primarily on these reduced numbers.[95] Since Drake had not equipped the voyage for colonization, he would not have placed any settlers along the coast.[96] Furthermore, Drake was undoubtedly aware that England would have trouble enforcing its claim by supporting a colony in a land so remote as New Albion.[97]

The only person confirmed as left behind at New Albion was N. de Morena, a European ship pilot who was in ill health. Left ashore, he recovered his health and embarked on a successful four-year journey by walking to Mexico.[98]

Land and climate

The typical weather conditions of the area—which correspond to those described in Fletcher's narrative[99]—are moderated by the Pacific Ocean which does much to prevent temperature extremes.[100] The summer days are often foggy, especially close to the surf. In 1579, Fletcher unhappily characterized the summer climate of the area, writing “...those mists and most stinking fogges ...” and noted that the continuous nipping chill often forced them to wear their winter clothes.[101] Even today, irrespective of the season, visitors to the area are advised to prepare for cool weather.[102] Today, during the same summer months as when Drake encamped at Point Reyes, contemporary weather is similar. In contrast to the temperatures at the headlands and beaches, a few miles inland the temperatures are often 20 degrees warmer (+11 °C degrees) and seldom hung with fog throughout the day.[103]

After Drake met the Coast Miwok and understood it was safe to explore to visit their villages, he did so by crossing an interior ridge. He found much the same climate contrast when he forayed up and into the region—miles from the surf—and experienced a flourishing land.[104] Fletcher assessed the area after using a Coast Miwok trail and crossing an interior ridge into what is now the Olema Valley:[105] “The inland we found to be farre different from the shoare, a goodly country and fruitful soyle, stored with many blessings fit for the use of man . . . .”[106] He observed certain animals unknown to the English and described them as “very large and fat Deere” and “a multitude of a strange kinde of Conies."[107] The "fat Deere" were most likely Roosevelt Elk, and the conies are identified as gophers.[108] These, and the rest, of Fletcher's assessments and observations of New Albion are flawlessly in concert with the geography of the Point Reyes.[109]

Drake landed in a region with diverse vegetation. The headlands and shore of Point Reyes are habitats to several types of native bushes, including bush lupine (Lupinus arboreus), coyote bush (Baccharis pilularis), and blue blossom (Ceanothus thyrsiflorus).[110] Although less than one percent of California's native grassland is still intact today, the area of Drake's landing has abundant amounts of various native grasses still growing today. The dominate grasses are perennial bunchgrasses, specifically Purple needlegrass (Nassella pulchra), California fescue (Festuca californica), and California oatgrass (Danthonia californica), all of which can remain green the entire year due to moisture provided by the persistent fog.[11] Inland—which is the area Drake would have seen when he crossed into the interior to visit with Coast Miwok—are several species of native trees. These trees, all used by used by the Coast Miwok, are the California Buckeye (Aesculus californica), Bishop Pine (Pinus muricata), and Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia). [12]

Today, the headlands and much of the interior of the Point Reyes area are part of Point Reyes National Seashore. Inverness, Inverness Park, Bolinas, Olema, and Point Reyes Station are communities in the area.

| Climate data for Bear Valley Visitor Center (inland area visited by Drake [111]), Point Reyes, CA (Jan 2006 - Dec 2015) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

61 (16) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

68 (20) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

73 (23) |

74 (23) |

72 (22) |

65 (18) |

56 (13) |

67 (19) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 40 (4) |

42 (6) |

43 (6) |

44 (7) |

47 (8) |

50 (10) |

52 (11) |

52 (11) |

51 (11) |

49 (9) |

44 (7) |

40 (4) |

46 (8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.1 (104) |

5.4 (137) |

4.1 (104) |

2.6 (66) |

0.8 (20) |

0.4 (10) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.3 (8) |

1.9 (48) |

2.9 (74) |

6.3 (160) |

28.8 (731) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[112] | |||||||||||||

Other ideas suggesting alternative locations

Considering that in excess of twenty other locations have been advanced as the site of Drake's port, more information has been printed regarding the location of New Albion than any other New World harbor that Drake sought.[113] Describing their lack of seamanship experience and navigational knowledge, Davidson recognizes a plethora of confusion, chiefly from armchair historians which include distinguished persons such as Samuel Johnson and Jules Verne.[114][115] Additionally, controversy has also raged for decades due to researchers' varying personal motives.[116]

Point San Quentin, San Francisco Bay, California

Robert H. Power (1926–1991), co-owner of the Nut Tree in Vacaville, CA, promoted the idea that Drake's New Albion was inside present day San Francisco Bay near Point San Quentin (37°56′22″N 122°29′12″W / 37.939400°N 122.486700°W). Among his arguments was that the Hondius Broadside map matched a part of the topography when parts were adjusted using a 2:1 correction.[117]

Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada

In 2003 Canadian R. Samuel Bawlf suggested that Drake's landing was on present day Vancouver Island at Comox, British Columbia (49°40′N 124°57′W / 49.66°N 124.95°W). Bawlf supported the idea that Drake completed the "Neahkahnie Mountain Survey," and he believed Drake careened the Golden Hind in Whale Cove, Oregon. Bawlf pointed to a number of pieces of evidence in support of his view that the official published record of Drake's voyage was deliberately altered to suppress the true extent of his discoveries. Bawlf also relied heavily upon the configuration of the coastline as depicted in some of the maps and globes of the era, including the so-called French and Dutch Drake Maps and Richard Hakluyt's 1587 map of the New World which Bawlf believed indicate a more-northerly location.[118]

Plate of Brass

Richard Hakluyt wrote of a particular, distinctive plate which Drake installed at New Albion: “At our departure hence our General set up a monument of our being there, as also of her Majesty's right and title to the same; namely a plate, nailed upon a fair great post, whereupon was engraved her Majesty's name, the day and year of our arrival there, with the free giving up of the province and people into her Majesty's hands, together with her Highness' picture and arms, in a piece of six pence of current English money, under the plate, whereunder was also written the name of our General.[119] Similarly, Fletcher's narrative states that an engraved plate of brass, with a sixpence bearing the Queen's likeness affixed to it, was attached to a “. . . great and firme post . . . ."[120] This plate served tangible notice of England's sovereignty over the land,[121] and given that the original plate has yet to be found, the exact location of the monument is unknown.[122]

In 1936, a counterfeit, the so-called Drake's Plate of Brass, came to public attention, and for decades its discovery was believed to be that of the original. While accepted by the University of California, Berkeley, as authentic, doubts persisted. Eventually, in the late 1970s, scientists determined—after it failed a battery of metallurgical tests—that the plate was a modern creation.[123] In 2003, it was publicly revealed that the counterfeit plate was created as a practical joke among local historians. Spinning out of control, the joke unintentionally became a public hoax and embarrassment to those who had once confirmed its authenticity.[124]

Localized legacy

The localized legacy of Drake's New Albion claim is evident in several ways. The inspiration of various local namesakes is owed to the notion of this declaration. New Albion Brewing Company, located near Drake's 1579 landing, is the first United States microbrewery of the modern era, 36[125] and Sir Francis Drake High School is located in San Anselmo, California, several miles southeast of Drake's landing.[126]

Also near Drake's landing is Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, an arterial road running east-west in Marin County, California. The Prayerbook Cross, also known as the Drake Cross, erected in 1894 in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, was donated by the Church of England to commemorate the 1579 church services held by Drake's chaplain, claiming they were the first ever held in English in the region.[127]

Several commemorative and historical societies have been founded—not only to celebrate and research Drake's landing in Northern California—but also to investigate speculative sites. These include the Sir Francis Drake Association,[128] the Sir Francis Drake Society [129] and the Drake Navigators Guild.[130]

See also

Further reading

- Drake, Francis. Archibald L., Hettrich, ed. Sir Francis Drake, description of his landing at Drake's Bay, Marin County, California, June 17, 1579.

References

- ↑ Oko, Captain Adolph S., Jr., Francis Drake and Nova Albion, California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XLIII, No. 2, June 1964, page 135

- ↑ Sugden, John (1990). Sir Francis Drake. New York: Touchstone. pp. 92–98. ISBN 978-0-671-75863-9.

- ↑ Wallis 1979, p. 2

- ↑ Sudgen 1990, pp. 98, 109, 110

- ↑ "Sir Francis Drake". Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ Woodard, Colin (2007). The Republic Of Pirates. New York and Boston: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-15-101302-9.

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 101

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p.98

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 132

- ↑ Inventory and Analysis of Coastal and Submerged Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Pacific Outer Continental Shelf (PDF), U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 130

- ↑ Oko 1964, p. 152

- ↑ Von der Porten, Edward (January 1975). "Drake's First Landfall". Pacific Discovery, California Academy of Sciences. 28 (1): 28–30.

- ↑ {Sugden 1990, p. 136

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 137

- ↑ Turner, Michael (2006). In Drake's Wake Volume 2 The World Voyage. United Kingdom: Paul Mould Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-904959-28-1.

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 135

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 183

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 144

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 149

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 151

- ↑ Stow, John (1984). Sir Francis Drake and the famous voyage, 1577–1580 : essays commemorating the quadricentennial of Drake's circumnavigation of the earth. Oakland: University of California Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0520048768.

- ↑ Polk, Dora (1995). The Island of California: A History of The Myth. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. p. 241. ISBN 9780803287419.

- ↑ Wallis, Helen (1979). The Voyage of Sir Francis Drake Mapped in Silver And Gold. Berkeley: Friends of the Bancroft Library, University of California. p. 1.

- ↑ Wallis 1979, p. 1

- ↑ Wallis 1979, p. 5

- ↑ Wallis 1979, p. 7

- ↑ Wallis 1979, p. 8

- ↑ Wallis 1979, p. 20

- ↑ Wallis 1979, p. 20

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 111

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 118

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 118

- ↑ Inventory and Analysis of Coastal and Submerged Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Pacific Outer Continental Shelf (PDF), U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Gough, Barry (1992). The Northwest Coast: British Navigation, Trade and Discoveries to 1812. Vancouver: Univ. of British Columbia Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0774803991.

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 157

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 137

- ↑ Woodward, William (1899). A Short History of the Expansion of the British Empire, 1500–1870. Cambridge: University Press. p. 34.

- ↑ Woodward 1890 p. 33

- ↑ Woodward 1899, p. 39

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 137

- ↑ A Perfect Description of Virginia, 1837, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Drake's likely 380 NM route (GoogleEarth)

- ↑ Site Of Sir Francis Drake's Ship Grounding Honored At Point Reyes National Seashore, National Parks Traveler, U.S. National Park Service, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 169

- ↑ Site Of Sir Francis Drake's Ship Grounding Honored At Point Reyes National Seashore, National Parks Traveler, U.S. National Park Service, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Wagner, Henry R. (1926). Sir Francis Drake's Voyage Around the World: Its Aims and Achievemennts. John Howell. p. 161.

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 290

- ↑ Davidson, George (1887). Annual Report of The Director. Washington: U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Government Printing Office. p. 214.

- ↑ Davidson, George (1890). Identification of Francis Drake's Anchorage on the Coast of California in the year 1579. San Francisco. p. 8.

- ↑ Davidson, George (1908). Francis Drake on the Northwest Coast of America in the Year 1579: The Golden Hind Did Not Anchor in the Bay Of San Francisco. San Francisco: F.F. Partridge. p. 108.

- ↑ "Robert Fleming Heizer, July 13, 1959-July 18 1979", nap.edu, The National Academies Press, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Heizer, Robert (1947). Francis Drake And The California Indians, 1579. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-5005-93599.

- ↑ Oko, Captain Adolph S., Jr. "Francis Drake and Nova Albion". California Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. XLIII, No. 2, June 1964

- ↑ Nimitz, Chester W., "Drake's Cove", Pacific Discovery, California Academy of Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 2, 1958.

- ↑ Francis Drake's Port Visible Again at Point Reyes National Seashore, U. S. National Park Service, retrieved 27 March 2009

- ↑ Shangraw, Clarence; Von der Porten, Edward (1981). The Drake And Cermeño Expeditions' Chinese Porcelains At Drakes Bay, California 1579 And 1595. Santa Rosa, California: Santa Rosa Junior College. p. 73.

- ↑ Kuwayama, George (1997). Chinese Ceramics in Colonial Mexico (Lacm). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'iI Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0875871790.

- ↑ Kuwayama, 1997, p. 273

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 290

- ↑ Sugden 1990, 130

- ↑ Meniketti, Marco (June 2013). "Preliminary Results of pXRF Testing of Porcelains from Sixteenth-Century Ship Cargos on the West Coast". Society for California Archaeology Newsletter. 47 (2): 17.

- ↑ Meniketti 2017, p. 17

- ↑ Cassels, Sir Simon (August 2003). "Where Did Drake Careen The Golden Hind in June/July 1579? A Mariner's Assessment". The Mariner's Mirror. 89 (1): 260–271.

- ↑ Meniketti 2017, p. 18

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 290

- ↑ Sugden, John (2006). Sir Francis Drake. Pimlico. p. 332.

- ↑ "Coast Miwok at Point Reyes", newsmaven.io, Indian Country Today, News Maven, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Heizer 2014, p. 15

- ↑ Coast Miwok at Point Reyes, Point Reyes National Seashore, U.S. National Park Service, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ "Coast Miwok at Point Reyes", Indian Country Today, News Maven, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ California Indians Language Groups, California Department of Parks and Recreation, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Heizer 2014, p. 12

- ↑ Heizer 2014. p. 12

- ↑ "Coast Miwok at Point Reyes", Indian Country Today, News Maven, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 174

- ↑ Wilson, Derek (1947). The World Encompassed. London: Hamish Hamilton. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-0601-46795.

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 136

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 135

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 136

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 178

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 138

- ↑ Wilson 1947, p. 54

- ↑ Kule Loklo: A Coast Miwok Cultural Exhibit, Miwok Archelological Preserve Of Marin, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 181

- ↑ Brandon, William (2003). The Rise and Fall of North American Indians: From Prehistory through Geronimo. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-58979-036-0.

- ↑ Heizer 2014, p. 10

- ↑ Heizer 2014, p. 10

- ↑ Hudson, Travis (2015). Treasures from Native California: The Legacy of Russian Exploration. United Kingdom: Penguin Classics. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-61132-982-7.

- ↑ Heizer 2014, p. 10

- ↑ Teacher's Resource Handbook: Environmental Living Program, Tomales State Park (PDF), California Department of Parks and Recreation, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Coast Miwok at Point Reyes, Indian Country Today, News Maven, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Heizer 2014, p. 10

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 177

- ↑ Cummins, John (1997). Francis Drake: Lives of a Hero. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 118. ISBN 978-0312163655.

- ↑ Inventory and Analysis of Coastal and Submerged Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Pacific Outer Continental Shelf (PDF), U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Sugden 2006, p. 118, 137

- ↑ Pioneers of the Far West. The Earliest History of California, New Mexico, etc. From Documents Never Before Published In English, The Land Of Sunshine: The Magazine Of California And The West. Hathi Trust Digital Library, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Sudgen 1990, p. 135

- ↑ Point Reyes National Seashore Weather and Tides, U.S. National Park Service, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Wilson 1947, p. 52

- ↑ "Point Reyes Weather Center", ptreyes.org, Point Reyes National Seashore Association, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ "Point Reyes National Seashore Weather and Tides", nps.gov, U.S. National Park Service, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 170

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 180

- ↑ Wilson 1947, p. 62

- ↑ Wilson 1947, p. 62

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 181

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 170

- ↑ Point Reyes National Seashore Trees and Shrubs, U.S. National Park Service, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 180

- ↑ Data Explorer: Time Series Values for Individual Locations, Prism Climate Group, Oregon State University, retrieved 17 August 2018

- ↑ Sugden 1990, p. 133

- ↑ Davidson 1908, p. 106

- ↑ Oko, Captain Adolph S., Jr., "Francis Drake and Nova Albion". California Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. XLIII, No. 2, June 1964, pp. 140,141

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 168

- ↑ Power, Robert (1974). Francis Drake & San Francisco Bay: a Beginning of the British Empire. University of California, Davis.

- ↑ Bawlf, R. Samuel (2003). The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake, 1577–1580. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55054-977-5.

- ↑ Hakluyt, Richard (2015). The Voyage Of Sir Francis Drake around The Whole Globe. United Kingdom: Penguin Classics. p. 15,16. ISBN 978-0-141-39851-8.

- ↑ Wilson 1947, p. 62

- ↑ Turner 2006, p. 178

- ↑ Kathleen Maclay. . Who made Drake's "plate of brasse"?, UC Berkeley News, 2003. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ↑ Paul, Craddock (2009). Scientific Investigation of Copies, Fakes and Forgeries. Oxford, United Kingdom: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-7506-4205-7.

- ↑ Edward Von der Porten, Raymond Aker, Robert W. Allen, James M. Spitze. "Who Made Drake's Plate of Brass? Hint: It Wasn't Francis Drake" California History, Vol. 81, No. 2 (2002), pp. 116–133

- ↑ "New York's Beer Debt to California". observer.com. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ "Feature Detail Report For: Sir Francis Drake High School". USGS.gov. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ "Prayer-Book Cross Dedicated" (PDF). Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ "Sir Francis Drake Association records, 1914-1949".

- ↑ "100 Marin Residents Make Pilgrimage To Drake's Bay". San Rafael: Daily Independent Journal. 1949-10-10.

- ↑ "Ed Von der Porten, Expert on Drake's Visit to California, dies at 84". Retrieved 9 August 2018.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Albion. |