Heligoland

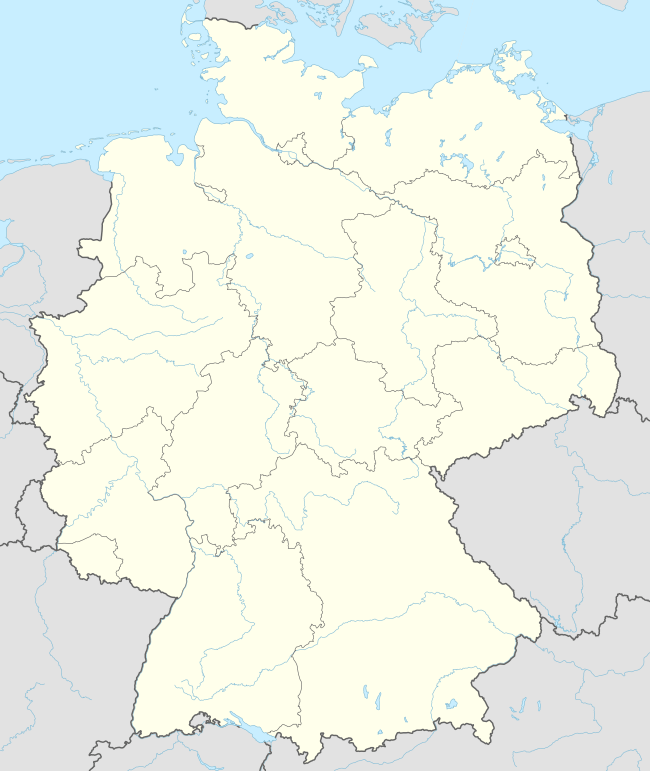

| Heligoland Helgoland | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

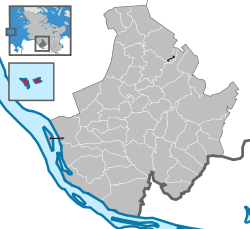

Heligoland Location of Heligoland within Pinneberg district  | |||

| Coordinates: 54°10′57″N 7°53′07″E / 54.18250°N 7.88528°ECoordinates: 54°10′57″N 7°53′07″E / 54.18250°N 7.88528°E | |||

| Country | Germany | ||

| State | Schleswig-Holstein | ||

| District | Pinneberg | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Jörg Singer (Ind.) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 1.7 km2 (0.7 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 61 m (200 ft) | ||

| Population (2016-12-31)[1] | |||

| • Total | 1,357 | ||

| • Density | 800/km2 (2,100/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | ||

| Postal codes | 27498 | ||

| Dialling codes | 04725 | ||

| Vehicle registration | PI, AG | ||

| Website |

helgoland | ||

Heligoland (/ˈhɛlɪɡoʊlænd/; German: Helgoland [ˈhɛlɡolant]; Heligolandic Frisian: deät Lun lit. "the Land", Mooring Frisian: Hålilönj) is a small German archipelago in the North Sea.[2] The islands were at one time Danish and later British possessions.

The islands are located in the Heligoland Bight (part of the German Bight) in the southeastern corner of the North Sea, and had a population of 1,127 at the end of 2016. They are the only German islands not in the immediate vicinity of the mainland. They lie approximately 69 kilometres (43 miles) by sea from Cuxhaven at the mouth of the River Elbe. During the period of British possession, the lyrics to "Deutschlandlied", which became the national anthem of Germany, were written on one of the islands by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben in 1841, while he was vacationing there.

In addition to German, the local population, who are ethnic Frisians, speak the Heligolandic dialect of the North Frisian language called Halunder. Heligoland used to be called Heyligeland, or "holy land", possibly due to the island's long association with the god Forseti.

Geography

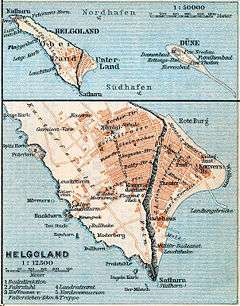

Heligoland is located 46 kilometres (29 mi) off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular 1 km2 (0.4 sq mi) main island (Hauptinsel) to the west, and the Düne ("dune", Heligolandic: de Halem) to the east. "Heligoland" generally refers to the former island. Düne is somewhat smaller at 0.7 km2 (0.27 sq mi), lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's airport.

The main island is commonly divided into the Unterland ("Lower Land", Heligolandic: deät Deelerlun) at sea level (to the right on the photograph, where the harbour is located), the Oberland ("Upper Land", Heligolandic: deät Boperlun) consisting of the plateau visible in the photographs and the Mittelland ("Middle Land") between them on one side of the island. The Mittelland came into being in 1947 as a result of explosions detonated by the British Royal Navy (the so-called "Big Bang"; see below).

The main island also features small beaches in the north and the south and drops to the sea 50 metres (160 ft) high in the north, west and southwest. In the latter, the ground continues to drop underwater to a depth of 56 metres (184 ft) below sea level. Heligoland's most famous landmark is the Lange Anna ("Long Anna" or "Tall Anna"), a free standing rock column (or stack), 47 metres (154 ft) high, found northwest of the island proper.

The two islands were connected until 1720, when the natural connection was destroyed by a storm flood. The highest point is on the main island, reaching 61 metres (200 ft) above sea level.

Although culturally closer to North Frisia in the German district of Nordfriesland, the two islands are part of the district of Pinneberg in the state of Schleswig-Holstein. The main island has a good harbour and is frequented mostly by sailing yachts.

History

The German Bight and the area around the island is known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times. Flint tools have been recovered from the bottom of the sea surrounding Heligoland. On the Oberland, prehistoric burial mounds were visible until the late 19th century and excavations showed skeletons and artefacts. Moreover, prehistoric copper plates have been found under water near the island; those plates were almost certainly made on the Oberland.[3]

In 697, Radbod, the last Frisian king, retreated to the then-single island after his defeat by the Franks—so it is written in the Life of Willebrord by Alcuin. By 1231, the island was listed as the property of the Danish king Valdemar II. Archaeological findings from the 12th to 14th century suggest the processing of copper ore on the island.[4]

There is a general understanding that the name Heligoland in origin means "Holy Land" (cf. modern Dutch and German heilig, "holy").[5] In the course of the centuries several alternative theories have been proposed, explaining the name from a Danish king Heligo or from the Frisian word hallig, meaning "salt marsh island". In this sense, the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica suggests an etymology of "Hallaglun, or Halligland, i.e. 'land of banks, which cover and uncover'".[6]

Traditional economic activities included fishing, hunting birds and seals, wrecking and—very important for many overseas powers—piloting overseas ships into the harbours of Hanseatic League cities such as Bremen and Hamburg. Moreover, in some periods Heligoland was an excellent base point for huge herring catches. As a result, until 1714 ownership switched several times between Denmark and the Duchy of Schleswig, with one period of control by Hamburg. In August 1714, it was captured by Denmark, and it remained Danish until 1807.

19th century

| British Administration of Heligoland Britische Verwaltung von Helgoland (German) | |||||

| British Crown Colony | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Government | Colony | ||||

| Monarch | |||||

| • | 1807–1820 (first) | George III | |||

| • | 1837–1890 (last) | Victoria | |||

| Lieutenant Governor/Governor[7] | |||||

| • | 1807–1814 (first) | Corbet James d'Auvergne | |||

| • | 1888–1890 (last) | Arthur Cecil Stuart Barkly | |||

| Historical era | |||||

| • | Treaty of Kiel | 1807 | |||

| • | Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty | 1890 | |||

| Today part of | |||||

On 11 September 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars, HMS Carrier brought to the Admiralty the despatches from Admiral Thomas Macnamara Russell announcing Heligoland's capitulation to the British.[8] Heligoland became a centre of smuggling and espionage against Napoleon. Denmark then ceded Heligoland to George III of the United Kingdom by the Treaty of Kiel (14 January 1814). Thousands of Germans came to Britain and joined the King's German Legion via Heligoland.

The British annexation of Heligoland was ratified by the Treaty of Paris signed on 30 May 1814, as part of a number of territorial reallocations following on the abdication of Napoleon as Emperor of the French.

The prime reason at the time for Britain's retention of a small and seemingly worthless acquisition was to restrict any future French naval aggression against the Scandinavian or German states.[9] In the event no effort was made during the period of British administration to make use of the islands for naval purposes, partly for financial reasons but principally because the Royal Navy considered Heligoland to be too exposed as a forward base.[10]

In 1826, Heligoland became a seaside spa and soon turned into a popular tourist resort for the European upper class. The island attracted artists and writers, especially from Germany and Austria who apparently enjoyed the comparatively liberal atmosphere, including Heinrich Heine and August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben. More vitally it was a refuge for revolutionaries of the 1830s and the 1848 German revolution.

As related in the Leisure Hour, it was "a land where there are no bankers, no lawyers, and no crime; where all gratuities are strictly forbidden, the landladies are all honest and the boatmen take no tips", while the English Illustrated Magazine provided a description the most glowing terms: "No one should go there who cannot be content with the charms of brilliant light, of ever-changing atmospheric effects, of a land free from the countless discomforts of a large and busy population, and of an air that tastes like draughts of life itself."

Britain gave up the islands to Germany in 1890 in the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty. The newly unified Germany was concerned about a foreign power controlling land from which it could command the western entrance to the militarily-important Kiel Canal, then under construction along with other naval installations in the area and thus traded for it. A "grandfathering"/optant approach prevented the Heligolanders (as they were named in the British measures) from forfeiting advantages because of this imposed change of status.

Heligoland has an important place in the history of the study of ornithology, and especially the understanding of migration. The book Heligoland, an Ornithological Observatory by Heinrich Gätke, published in German in 1890 and in English in 1895, described an astonishing array of migrant birds on the island and was a major influence on future studies of bird migration, in Britain in particular.

20th century

Under the German Empire, the islands became a major naval base, and during the First World War the civilian population was evacuated to the mainland. The island was fortified with concrete gun emplacements along its cliffs similar to the Rock of Gibraltar. Island defenses included 364 mounted guns including 142 42-centimetre (17 in) disappearing guns overlooking shipping channels defended with ten rows of naval mines.[11] The first naval engagement of the war, the Battle of Heligoland Bight, was fought nearby in the first month of the war. The islanders returned in 1918, but during the Nazi era the naval base was reactivated. Lager Helgoland, the German labour camp on Alderney, was named after the island.

Werner Heisenberg (1901–1975) first formulated the equation underlying his picture of quantum mechanics while on Heligoland in the 1920s. While a student of Arnold Sommerfeld at Munich in the early 1920s, Heisenberg first met the Danish physicist Niels Bohr. He and Bohr went for long hikes in the mountains and discussed the failure of existing theories to account for the new experimental results on the quantum structure of matter. Following these discussions, Heisenberg plunged into several months of intensive theoretical research, but met with continual frustration. Finally, suffering from a severe attack of hay fever, he retreated to the treeless (and pollenless) island of Heligoland in the summer of 1925. There he conceived the basis of the quantum theory.

In 1937, construction began on a major reclamation project (Project Hummerschere) intended to expand existing naval facilities and restore the island to its pre-1629 dimensions. The project was largely abandoned after the start of World War II and was never completed.

World War II

The area was the setting of the aerial Battle of the Heligoland Bight in 1939, a result of British bombing attempts on German Navy vessels in that area. The area's waters were frequently mined by British aircraft.

Heligoland also had military function as a sea fortress in the Second World War. Completed and ready for use were the submarine bunker North sea III, the coastal artillery, an air-raid shelter system with extensive bunker tunnels and the airfield with the air force – Jagdstaffel Helgoland (April to October 1943).[12] Forced labour of, among others, citizens of the Soviet Union was used during the construction of military installations during World War II.[13]

On 3 December 1939, Heligoland was bombed by the Allies for the first time. The attack, by twenty four Wellington bombers of RAF Squadrons 38, 115 and 149, failed to destroy its target of German warships at anchor.[14]

Within three days in early 1940, the Royal Navy lost three submarines in Heligoland: HMS Undine (N48) on 6 January, HMS Seahorse (98S) on 7 January and HMS Starfish on 9 January.[15]

Early in the war, the island was little affected by bombing. This shows the minor military significance of the island for British forces. Through the development of the Luftwaffe, the island had largely lost its strategic importance. The Jagdstaffel Helgoland, temporarily used for defense against Allied bombing, was equipped with a rare version of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter originally designed for use on aircraft carriers.

Shortly before the war ended in 1945, Georg Braun and Erich Friedrichs succeeded in forming a resistance group. However, shortly before they were to execute the plans, they were betrayed by two members of the group. About twenty men were arrested on 18 April 1945; fourteen of them were transported to Cuxhaven. After a short trial, five resisters were executed by firing squad at Cuxhaven-Sahlenburg on 21 April 1945.[16]

To honour them, in April 2010 the Helgoland Museum installed six stumbling blocks on the roads of Heligoland. Their names are Erich P. J. Friedrichs, Georg E. Braun, Karl Fnouka, Kurt A. Pester, Martin O. Wachtel, and Heinrich Prüß.

With two waves of attacks on 18 and 19 April 1945, 1,000 aircraft of the British Royal Air Force dropped about 7,000 bombs. The majority of the population survived in the bomb shelters. 285 people were killed, including many Luftwaffenhelfer and naval auxiliaries.[17] 128 of the casualties were anti-aircraft crew. The bomb attacks rendered the island uninhabitable, and it was evacuated.

| Date/Target | Result |

|---|---|

| 11 March – 24 August 1944 | No. 466 Squadron RAAF conducted minelaying operations.[18] |

| 18 April 1944 | No. 466 Squadron RAAF conducted bombing operations.[18] |

| 29 August 1944 | Mission 584: 11 B-17 Flying Fortresses and 34 B-24 Liberators bomb Heligoland Island; 3 B-24s are damaged. Escort is provided by 169 P-38 Lightnings and P-51 Mustangs; 7 P-51s are damaged.[19] |

| 3 September 1944 | Operation Aphrodite B-17 63954 attempt on U-boat pens[20] failed when US Navy controller flew aircraft into Düne Island by mistake. |

| 11 September 1944 | Operation Aphrodite B-17 30180 attempt on U-boat pens[20] hit by enemy flak and crashed into sea. |

| 29–30 September 1944 | 15 Lancasters conducted minelaying in the Kattegat and off Heligoland. No aircraft lost.[21] |

| 5–6 October 1944 | 10 Halifaxes conducted minelaying off Heligoland. No aircraft lost.[21] |

| 15 October 1944 | Operation Aphrodite B-17 30039 *Liberty Belle* and B-17 37743 attempt on U-boat pens[22] destroyed many of the buildings of the Unterland. |

| 26–27 October 1944 | 10 Lancasters of No 1 Group conducted minelaying off Heligoland. 1 Lancaster minelayer lost.[21] and the islands were evacuated the following night. |

| 22–23 November 1944 | 17 Lancasters conducted minelaying off Heligoland and in the mouth of the River Elbe without loss.[21] |

| 23 November 1944 | 4 Mosquitoes conducted Ranger patrols in the Heligoland area. No aircraft lost.[21] |

| 31 December 1944 | On Eighth Air Force Mission 772, 1 B-17 bombed Heligoland island.[23] |

| 4–5 February 1945 | 15 Lancasters and 12 Halifaxes minelaying off Heligoland and in the River Elbe. No minelaying aircraft lost.[21] |

| 16–17 March 1945 | 12 Halifaxes and 12 Lancasters minelaying in the Kattegat and off Heligoland. No aircraft lost.[24] |

| 18 April 1945 | 969 aircraft: 617 Lancasters, 332 Halifaxes, 20 Mosquitoes bombed the Naval base, airfield, & village into crater-pitted moonscapes. 3 Halifaxes were lost. The islands were evacuated the following day.[25] |

| 19 April 1945 | 36 Lancasters of 9 and 617 Squadrons attacked coastal battery positions with Tallboy bombs for no losses.[25] |

Explosion

From 1945 to 1952 the uninhabited Heligoland islands were used as a bombing range. On 18 April 1947, the Royal Navy detonated 6,700 tonnes of explosives ("Big Bang" or "British Bang"), creating one of the biggest single non-nuclear detonations in history.[26] Though the attack was aimed at the fortifications, the island's total destruction would have been accepted.[27] The blow shook the main island several miles down to its base, changing its shape (the Mittelland was created).

On 20 December 1950, two students and a professor from Heidelberg – René Leudesdorff, Georg von Hatzfeld and Hubertus zu Löwenstein – occupied the off-limits island and raised various German, European and local flags.[28] The students were arrested by the British military and brought back to the mainland. The event started a movement to restore the islands to Germany, which gained the support of the German parliament. On 1 March 1952, Heligoland was returned to German control, and the former inhabitants were allowed to return.[29] The first of March is an official holiday on the island. The German authorities had to clear a huge amount of undetonated ammunition, landscape the main island, and rebuild the houses before it could be resettled.

Modern day

Heligoland is now a holiday resort and enjoys a tax-exempt status, as it is part of the EU but excluded from the EU VAT area and customs union. Consequently, much of the economy is founded on sales of cigarettes, alcoholic beverages and perfume to tourists who visit the islands. The ornithological heritage of Heligoland has also been re-established, with the Heligoland Bird Observatory, now managed by the Ornithologische Arbeitsgemeinschaft Helgoland e.V. ("Ornithological Society of Heligoland") which was founded in 1991. A search and rescue (SAR) base of the DGzRS, the Deutsche Gesellschaft zur Rettung Schiffbrüchiger (German Maritime Search and Rescue Service), is located on Heligoland.

Energy supply

Before the island was connected to the mainland network by a submarine cable in 2009, electricity on Heligoland was generated by a local diesel plant.

Heligoland was the site of a trial of GROWIAN, a large wind turbine testing project. In 1990, a 1.2 MW turbine of the MAN type WKA 60 was installed. Besides technical problems, the turbine was not lightning proof and insurance companies would not provide coverage. The wind energy project was viewed as a failure by the islanders and was stopped.[30][31] The submarine cable in use now has a length of 53 kilometres (33 mi) and is one of the longest AC submarine power cables in the world and the longest of its kind in Germany.[32] It was manufactured by the North German Seacable Works in a single piece and was laid by the barge Nostag 10 in spring 2009. The Heligoland Power Cable, which is designed for an operational voltage of 30 kV, reaches the German mainland at Sankt Peter-Ording.

Expansion plans and wind industry

Plans to re-enlarge the land bridge between different parts of the island by means of land reclamation came up between 2008 and 2010.[33] However, the local community voted against the project.[34][35]

Since 2013, a new industrial site is being expanded on the southern harbour. E.ON, RWE and WindMW plan to manage operation and services of large offshore windparks from Heligoland.[36][37][38] The range had been cleaned of left-over ammunition.[39]

Climate

The climate of Heligoland is typical of an offshore climate, being almost free of pollen and thus ideal for people with pollen allergies. Since there is no land mass in the vicinity, temperatures rarely drop below −5 °C (23 °F) even in the winter. At times, winter temperatures can be higher than in Hamburg by up to 10 °C (18 °F) because cold winds from Russia are weakened. While spring tends to be comparatively cool, autumn on Heligoland is often longer and warmer than on the mainland, and statistically, the climate is generally sunnier. The coldest temperature ever recorded on Heligoland was −11.2 °C (12 °F) in February 1956, while the highest was 28.7 °C (84 °F) in July 1994.

Owing to the mild climate, figs have reportedly been grown on the island as early as 1911,[40] and a 2005 article mentioned Japanese bananas, figs, agaves, palm trees and other exotic plants that had been planted on Heligoland and were thriving.[41] There still is an old mulberry tree in the Upper Town.

| Climate data for Heligoland, 1981–2010 (sunshine 1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.1 (52) |

11.1 (52) |

12.8 (55) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.9 (75) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.1 (61) |

18.9 (66) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

2.8 (37) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.3 (45.1) |

11.1 (52) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.3 (41.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.2 (54) |

15.0 (59) |

15.7 (60.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.7 (12.7) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.0 (41) |

7.2 (45) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.4 (2.299) |

42.5 (1.673) |

49.5 (1.949) |

33.9 (1.335) |

41.6 (1.638) |

54.4 (2.142) |

63.6 (2.504) |

79.7 (3.138) |

87.4 (3.441) |

87.0 (3.425) |

78.9 (3.106) |

67.5 (2.657) |

744.4 (29.307) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 46.5 | 79.1 | 120.9 | 177.0 | 241.8 | 237.0 | 223.2 | 220.1 | 147.0 | 99.2 | 54.0 | 40.3 | 1,686 |

| Source #1: Météo Climat[42] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: German Meteorological Service[43] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Heligoland, 1990–2014 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.5 (2.224) |

41.9 (1.65) |

37.4 (1.472) |

34.4 (1.354) |

41.4 (1.63) |

55.9 (2.201) |

101.9 (4.012) |

85.6 (3.37) |

89.2 (3.512) |

86.0 (3.386) |

72.7 (2.862) |

72.4 (2.85) |

775.1 (30.516) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 44.9 | 64.4 | 125.3 | 182.4 | 231.9 | 225.4 | 227.6 | 204.7 | 141.6 | 98.3 | 48.5 | 37.1 | 1,632 |

| Source: WeatherOnline.co.uk[44] | |||||||||||||

Geology

The island of Heligoland is a geological oddity; the presence of the main island's characteristic red sedimentary rock in the middle of the German Bight is unusual. It is the only such formation of cliffs along the continental coast of the North Sea. The formation itself, called the Bunter sandstone or Buntsandstein, is from the early Triassic geologic age. It is older than the white chalk that underlies the island Düne, the same rock that forms the white cliffs of Dover in England and cliffs of Danish and German islands in the Baltic Sea. In fact, a small chalk rock close to Heligoland, called witt Kliff[45] (white cliff), is known to have existed within sight of the island to the west until the early 18th century, when storm floods finally eroded it to below sea level.

Heligoland's rock is significantly harder than the postglacial sediments and sands forming the islands and coastlines to the east of the island. This is why the core of the island, which a thousand years ago was still surrounded by a large, low-lying marshland and sand dunes separated from coast in the east only by narrow channels, has remained to this day, although the onset of the North Sea has long eroded away all of its surroundings. A small piece of Heligoland's sand dunes remains—the sand isle just across the harbour called Düne (Dune). A referendum in June 2011 dismissed a proposal to reconnect the main island to the Düne islet with a landfill.[46]

Flag

The Heligoland flag is very similar to its coat of arms—it is a tricolour flag with three horizontal bars, from top to bottom: green, red and white. Each of the colours has its symbolic meaning, as expressed in its motto:

| German | Low German | North Frisian | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Grün ist das Land, |

Gröön is dat Land, |

Grön es det Lunn, |

Groen is dat land, |

Green is the land, 1 lit. "edge" or "coast" |

There is an alternative version in which the word Sand ("sand") is replaced with Strand ("beach").

Road restrictions

There are very few cars on Heligoland. A special section (§50) in the German traffic regulations (Straßenverkehrsordnung, abbr. StVO)[47] prohibits the use of automobiles and bicycles on the island. No other region in Germany has any exceptions to the general regulations in the StVO, although other North Sea islands, such as Baltrum, have also banned the public from using cars and motorbikes.

Except for the local ambulance van and the small firetrucks, the only motor vehicles on the island are electrically powered and used primarily for moving material. Kick scooters are sometimes used as substitutes for bicycles.

The island received its first police car on 17 January 2006. Until then the island's policemen moved on foot and by bicycle, being exempt from the bicycle ban.

Notable residents

- Peter Andresen Oelrichs (1781–1869) a lexicographer and linguist.

- Rear Admiral Sir John Hindmarsh (1785–1860), veteran of the Battle of Trafalgar and first governor of South Australia, was the governor of Heligoland 1840–56.

- Heinrich Gätke (1814–1897), artist and ornithologist

- August Uihlein (1842–1911) a German-American brewer, business executive and horse breeder

- Richard Mansfield (1857–1907), actor

- Robert Knud Friedrich Pilger (1876–1953) botanist born in Heligoland, specialised in the study of conifers.

- Eva von der Osten (1881–1936), the soprano, was born here.

- James Krüss (1926–1997) a German writer of children's and picture books, illustrator, poet, dramatist and scriptwriter

- Georg C. F. Greve (born 1973 in Heligoland) software developer, physicist and author

In culture

- Heligoland gave its name to the Heligoland trap, used in bird ringing.

- Anton Bruckner composed a large scale choral work based on text about Heligoland.

- The text of the German National Anthem was written by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben during his vacation on then British-governed Heligoland.

- British trip hop duo Massive Attack named their fifth album after the German archipelago.

- "Romance helgolandská" ("Heligoland Romance"), a poem by Jan Neruda from his collection Balady a romance, is named after the island.

Lieutenant-Governors of Heligoland (1807–1890)

- 1807–1808: Corbet James d'Auvergne

- 1808–1815: William Osborne Hamilton (1750-1818)

- 1815–1840: Sir Henry King

- 1840–1856: Sir John Hindmarsh[48]

- 1857–1863: Richard Pattinson[49]

- 1863–1881: Sir Henry Berkeley Fitzhardinge Maxse

- 1881–1888: Sir John Terence Nicholls O'Brien

- 1888–1890: Arthur Cecil Stuart Barkly

See also

- Forseti—A Norse god whose central place of worship was at Heligoland

- Location hypotheses of Atlantis—Heligoland is hypothesized as a possible location for Atlantis by the Austrian author Jürgen Spanuth.

- Postage stamps and postal history of Heligoland

References

- ↑ "Statistikamt Nord – Bevölkerung der Gemeinden in Schleswig-Holstein 4. Quartal 2016] (XLS-file)". Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein (in German).

- ↑ Drower, George (2011). Heligoland: The True Story of German Bight and the Island the Britain Forgot. The History Press. ISBN 9780752472805.

- ↑ Ritsema, Alex (2007). Heligoland, Past and Present. Lulu Press. pp. 21–3. ISBN 978-1-84753-190-2.

- ↑ University of Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein State Archaeological Museum, ed. (1986). Schleswig-Holstein in 150 archäologischen Funden (in German). Neumünster: Karl Wachholtz. ISBN 3-529-01829-5.

- ↑ Heligoland, Past and Present, p. 39, Alex Ritsema

- ↑

- ↑ "British Empire: Europe: Heligoland".

- ↑ "No. 16064". The London Gazette. 12 September 1807. p. 1192.

- ↑ Ashley Cooper, page 40 History Today January 2014

- ↑ Ashley Cooper, page 41 History Today January 2014

- ↑ Halsey, Francis Whiting (1920). History of the World War. Ten. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. p. 15.

- ↑ Holm, Michael. "Jagdstaffel Helgoland" (in German). Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ↑ Lager russischer Offiziere und Soldaten, Helgoland Nordost, auf spurensuche-kreis-pinneberg.de

- ↑ Seekrieg: 1939 Dezember (Württemberg State Library, Stuttgart). Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ bremerhaven.de. Unter den Wellen Teil 3 – Britische U-Boote vor Helgoland Archived 13 June 2015 at Archive.is. February 2013.

- ↑ Wolfgang Stelljes. Verräter kam aus den eigenen Reihen. In: Journal (weekend edition of Nordwest Zeitung), Volume 70, No. 84 (11–12 April 2015), s. 1.

- ↑ Imke Zimmermann: Im Schutz der roten Felsen – Bunker auf Helgoland, vom 19. April 2005, auf fr-online.de

- 1 2 466 Squadron Missions Archived 13 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "8th Air Force 1944 Chronicles". Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007. June, July, August, September, October.

- 1 2 "1942 USAAF Serial Numbers (42-57213 to 42-70685)". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Joseph F. Baugher. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Campaign Diary". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. UK Crown. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007. 1944: June Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine., July, August Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine., September Archived 14 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine., October Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine., November, December Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "1942 USAAF Serial Numbers (42-30032 to 42-39757)". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Joseph F. Baugher. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ↑ Combat Chronology of the US Army Air Forces – December 1944 Archived 11 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "RAF – RAF Homepage". Archived from the original on 6 July 2007.

- 1 2 "RAF – RAF Homepage". Archived from the original on 6 July 2007.

- ↑ "Der Tag, an dem Helgoland der Megabombe trotzte". Der Spiegel (in German). 13 April 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ Madsen, Chris (1998). "The Royal Navy and German naval disarmament, 1942–1947". Psychology Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-7-1464-823-1.

- ↑ Hermann Ehmer (1987), "Hubertus Prinz zu Löwenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 15, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 100–101 ; (full text online)

- ↑ "1. März 1952: Helgoland ist wieder deutsch" (in German). NDR. 1 March 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ Helgoland Weil der Wind sich dreht , Der Tagesspiegel, 15 September 2012 Dagmar Dehmer, in German

- ↑ Wind Energy Comes of Age, Paul GipeJohn Wiley & Sons, 14 April 1995, p. 108

- ↑ "Mit der Zukunft Geschichte schreiben". Dithmarscher Kreiszeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 19 July 2011.

- ↑ "Pläne für Landaufschüttung auf Helgoland vom Tisch". Die Welt (in German). 16 June 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Informationen zum Bürgerentscheid am 26. Juni 2011" (PDF) (in German). Gemeinde Helgoland. 14 June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2011.

- ↑ "Helgoländer stimmen gegen Inselvergrößerung". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 27 June 2011. (subscription required)

- ↑ "RWE, E.ON und WindMW stellen Pläne für Betriebsbasis auf Helgoland für Offshore-Windkraftwerke vor" (in German). RWE Innogy. 5 August 2011.

- ↑ Wehrmann, Anne-Katrin (2012). "Eine Insel im Wandel – vom 'Fuselfelsen' zum modernen 'Helgoland 3.0'". Hansa Maritime Journal (in German). No. 12. pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Wehrmann, Anne-Katrin (2013). "Offshore-Branche ist auf Helgoland angekommen". Hansa Maritime Journal (in German). No. 12. pp. 34–5.

- ↑ "Helgoland erfindet sich grundlegend neu". Segler-Zeitung (in German). No. 6. 2013. pp. 144–5.

- ↑ Adolphi, Klaus (March 2008). "Neues zur Flora von Helgoland" (PDF). Braunschweiger Geobotanische Arbeiten (in German). 9: 9–19. Citing Kuckuck, P. (1911). "Reife Feigen und subtropische Pflanzen auf Helgoland". Die Heimat (in German). Vol. 21. Kiel. pp. 19–24.

- ↑ Saße, Dörte (26 August 2005). "Helgoland und Sansibar: Die ungleichen Schwestern". Der Spiegel (in German).

- ↑ "Météo climat stats for Helgoland". Météo Climat. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ↑ "Langjährige Mittelwerte: 1961–1990" (in German). German Meteorological Service.

- ↑ "WeatherOnline.co.uk CLimate Robot Helgoland/Düne". WeatherOnline.co.uk.

- ↑ "Nautical chart "Helgoland"". Europäisches Segel-Informationssystem. Archived from the original on 5 August 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ↑ "Helgoländer stimmen gegen Inselvergrößerung". Kieler Nachrichten (in German). 26 June 2011. Archived from the original on 30 June 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ↑ "StVO – Einzelnorm".

- ↑ "No. 19899". The London Gazette. 29 September 1840. p. 2161.

- ↑ "No. 21976". The London Gazette. 10 March 1857. p. 945.

Further reading

Papers

- Charlier, C. (1947). "L'explosion d'Heligoland. – Discussion des observations effectuées à Uccle". Ciel et Terre (in French). 64: 193–214. Bibcode:1948C&T....64..193C.

- Gardner, N. (2008). "An island outpost: Helgoland". Hidden Europe Magazine (20): 2–7. ISSN 1860-6318. Historical synopsis with review of modern economy and society on Heligoland.

- Reich, H.; Foertsch, O.; Schulze, G. A. (1951). "Results of seismic observations in Germany on the Heligoland explosion of April 18, 1947". Journal of Geophysical Research. 56 (2): 147–156. Bibcode:1951JGR....56..147R. doi:10.1029/JZ056i002p00147.

Books

- Andres, Jörg: Insel Helgoland. Die »Seefestung« und ihr Erbe. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-86153-770-0.

- Black, William George (1888). Heligoland and the Islands of the North-Sea. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood.

- Dierschke, Jochen: Die Vogelwelt der Insel Helgoland. Missing Link E. G., 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-035437-3.

- Drower, George (2011). Heligoland: The True Story of German Bight and the Island That Britain Forgot. Stroud, UK: History Press. ISBN 9780752460673. (originally published in 2002, ISBN 0-7509-2600-7)

- Friederichs, A.: Wir wollten Helgoland retten – Auf den Spuren der Widerstandsgruppe von 1945. Museum Helgoland, 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-030405-7.

- Grahn-Hoek, Heike: Roter Flint und Heiliges Land Helgoland. Wachholtz-Verlag, Neumünster 2009, ISBN 978-3-529-02774-1.

- Ritsema, Alex (2007). Heligoland, Past and Present. Lulu Press. ISBN 1847531903.

- Wallmann, Eckhard: Eine Kolonie wird deutsch – Helgoland zwischen den Weltkriegen. Nordfriisk Instituut, Bredstedt 2012, ISBN 978-3-88007-376-0.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Heligoland. |

- Film clip of coast defenses

- Heligoland Tourist Board – includes an aerial photograph of Heligoland (front) and Düne (back).

- Site about planting palms on Heligoland

- Heligoland Web Cams

- Heligoland Bird Observatory

- Footage of Destruction of Heligoland fortifications April 1947