Fort Wool

|

Fort Wool | |

|

Fort Wool Island from the Miss Hampton boat cruise | |

| |

| Location | Island between Willoughby Spit and Old Point Comfort, Hampton, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°59′12″N 76°18′04″W / 36.98667°N 76.30111°WCoordinates: 36°59′12″N 76°18′04″W / 36.98667°N 76.30111°W |

| Area | 15 acres (6.1 ha) |

| Built | 1819 |

| NRHP reference # | 69000339[1] |

| VLR # | 114-0041 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 25, 1969 |

| Designated VLR | November 5, 1968[2] |

Fort Wool is a decommissioned island fortification located in the mouth of Hampton Roads, adjacent to the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT). Now officially known as Rip Raps Island, the fort has an elevation of 7 feet and sits near Old Point Comfort, Old Point Comfort Light, Willoughby Beach and Willoughby Spit, approximately one mile south of Fort Monroe.

Originally named Castle Calhoun after Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, the fort was renamed after Maj. Gen. John Ellis Wool during the civil war. It is noted on current nautical maps as Rip Raps.

Fort Wool was one of more than forty forts started after the War of 1812 when British forces sailed the Chesapeake Bay to burn the Capital.[3] Designed by Brigadier General of Engineers Simon Bernard, an expat Frenchman who had served as Napoleon's chief engineer, Fort Wool was constructed on a shoal of ballast stones dumped as sailing ships entered Hampton's harbor — and was originally intended to have three tiers of casemates and a parapet with 232 muzzle-loading cannons, although it never reached this size. Fort Wool was built to maintain a crossfire with Fort Monroe, located directly across the channel, thereby protecting the entrance to the harbor.[4]

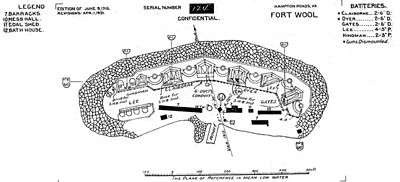

In 1902, as a result of the Endicott Board's findings,[5] all of the original fort, except for eight casemates, was demolished and new fortifications were constructed. The new armament mounted on five batteries of two to four guns remained in place for decades, with modifications made from time to time.[6] Only six of the original three-inch guns remained in 1942, when two were sent to nearby Fisherman Island. A modern battery of two new long-range six-inch guns was constructed over one of the old Endicott period batteries during World War II. The fort was decommissioned by the military in 1953.[7]

History

Brigadier-general of Engineers Simon Bernard was tasked by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun to create or improve fortifications for the protection of vital U.S. ports.[8] Bernard's plan was to build more than forty new forts, including Fort Wool, which he had named Fort Calhoun.[9] The fort was to have three tiers of casemates and a parapet with a total of 232 muzzle-loading cannons mounted, and was to be manned by a garrison of 1,000 soldiers. It was to built on a 15 acre (61,000 m²) artificial island southeast of Old Point Comfort in Hampton, Virginia. Construction got underway in 1819 when crews started dumping granite boulders into the water. It took four years to bring the rock pile up to the a 6-foot tall island called for in the plans.[10]

A controversy soon arose over the stones purchased for the island.[11] A nineteen-page report sent May 7, 1822 to the House of Representatives from the Military Affairs committee included depositions from individuals alleging that the contract to deliver 150,000 perches of stone at $3.00 per perch awarded to Elijah Mix on July 25, 1818 was fraudulent. Before awarding the contract, inquiries had been made at several quarries, and it was no secret that the government needed lots of stone for the project. The allegation was that the contract was awarded to Mix by General Joseph Swift of the War Department without advertising for bids. While other contracts had been awarded without advertising for bids as was standard procedure before April 1818, in April 1818 the newly reorganized United States Army Corps of Engineers required public notice be given for every contract after that date.[12]

Two proposals were received before the contract was awarded to Mix, and two more afterwards. All four of these proposals came in with higher bids than the one Mix offered. Many knowledgeable men agreed that the government had made a good deal, and the contractor had made a bad one for himself.[11]

In 1819, the controversy increased when Mix assigned half his contract to Major Christopher Van Deventer, who was chief clerk in the War Department.[11] Major Van Deventer and Mix were married to the daughters of Major Samuel Cooper, a noted Revolutionary War officer. Van Deventer later sold half of his interest to his father-in-law, Major Cooper. Secretary of War Calhoun had advised him that while what was done was not illegal, it "might expose Van Deventer to improper insinuations." Major Van Deventer deposed that he had no interest in the contract when it was first negotiated nor did he have any influence when the contract was awarded.[11] General Swift deposed that he felt Major Van Deventer had no interest in the contract when it was originally negotiated.[11] Major Cooper and Major Van Deventer sold their shares to Howes Goldsborough & Co. on July 1, 1820.[11][13]

Construction of the fort began in 1826, and after considerable delays caused by subsidence of the island, the first level of casemates was finally completed in 1830. Only ten guns were mounted. Construction continued through 1834, and only half of the second tier was completed. It was then found that Fort Calhoun's foundations had continued settling. A young second lieutenant and engineer in the U.S. Army, Robert E. Lee was transferred there to assist Captain Andrew Talcott, the U.S. Army engineer in charge of the construction of Fort Wool and its larger companion Fort Monroe, across the channel on the mainland. Lee was given the task of stabilizing the island as his first independent command. He found that the island wouldn't hold the weight of the two tiers of casemates and brought more stone in to stabilize it, but the fort never reached its intended size. Lee found the stone foundation under the fort was the problem, and that it would never support the weight of three tiers and parapet of the completed fort.[14]

Fort Wool also has a little-known association with presidents. President Andrew Jackson, broken hearted after the death of his wife and in frail health, came to Fort Wool in the late 1820s and the 1830s. Jackson made the fort his "White House." Jackson built a hut and would watch ships pass the island. He even made key policy decisions from the fort with cabinet advisers. Ironically President Jackson's Secretary of War John C. Calhoun had become the president's arch rival by this stage, by threatening to pull South Carolina out of the union. Later President John Tyler took sanctuary on the island after the death of his wife. Abraham Lincoln also visited the fort.[15]

Fort Wool even has an association with the actor Sir Alec Guinness, who was grounded in a minefield off the fort in World War II. The comedian Red Skelton also showed up at Fort Wool during the war to entertain troops.[15]

Civil War

The fort was originally named after John C. Calhoun, President Monroe's Secretary of War who was a Southern politician of secessionist tendencies, it was subsequently renamed after Maj. Gen. John Ellis Wool, a Mexican War hero and commander at Fort Monroe.[10]

A very powerful experimental cannon, the Sawyer Gun,[16] was installed at Fort Wool during the Civil War. The range of this weapon extended all the way to Sewell's Point, more than three miles away (where the Norfolk Naval Base is now located), the site of a Confederate earthen fort with bastions and a redan and three artillery batteries totaling of 45 guns. The Battle of Hampton Roads took place off Sewells Point on March 8–9, 1862. USS Monitor faced CSS Virginia during the Battle of the Ironclads in 1862. The Sawyer Gun also fired at Virginia, although it did no damage to the ironclad's armor.[17]

Endicott batteries

Five gun batteries were constructed after 1902, when funding became available to implement the recommendations of the Endicott board.[18]

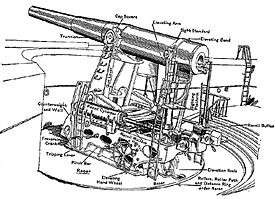

- Battery Ferdinand Claiborne: two shielded six-inch guns on disappearing carriages (1908-1918)

- Battery Alexander Dyer: two shielded six-inch guns on disappearing carriages (1908-1917)

- Battery Horatio Gates: two shielded six-inch guns on disappearing carriages (1908-1917)

- Battery Henry Lee (Battery 13): four 3-inch rapid-fire guns (1905-1946).

- Battery Jacob Hindman (Battery 14): two 3-inch rapid-fire guns (1905-1946)

World War I

In 1917 and 1918, all of the six-inch guns and disappearing carriages were removed.[18]

- Battery Ferdinand Claiborne: two shielded six-inch guns on disappearing carriages (1908-1918)

- Battery Alexander Dyer: two shielded six-inch guns on disappearing carriages (1908-1917)

- Battery Horatio Gates: two shielded six-inch guns on disappearing carriages (1908-1917)

- Battery Henry Lee (Battery 13): four 3-inch rapid-fire guns (1905-1946).

- Battery Jacob Hindman (Battery 14): two 3-inch rapid-fire guns (1905-1946)

- Submarine nets were stretched across the harbor from this point.[19]

- Submarine mines (called "torpedoes" at the time) stored here. The mines were controlled from Fort Monroe.

World War II

Additional armament and other changes were made after 1942:[18]

- Two Searchlight Towers replaced two 1921 wooden towers in 1930.

- Battery 229 (Battery 12) with two 6-inch shielded guns (1944) was constructed on the ruins of Battery Horatio Gates. The work was completed, and the shielded carriages were installed, however, the gun tubes were not mounted.

- 50 caliber and 37mm Anti-Aircraft Machine Guns.

- A modern Fire Control Tower replaced the original 1921 wooden tower.

- SCR 296 radar set and Tower for its antenna.

- A.A. Searchlight Tower.

- Submarine mines stored here. The mines were controlled from Fort Monroe.

Decommissioning

The fort was decommissioned in 1953[7] and given to the Commonwealth of Virginia. In the 1950s, the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT) was constructed next to Fort Wool, with its southern island connected to the fort by an earthen causeway. The HRBT opened to traffic in 1957. In 1967 and again in 1970, the City of Hampton developed the fort into a park, accessed by the passenger ferry, Miss Hampton II, which allows tourists boarding in Hampton to visit the island almost year-round. The fort can also be seen by westbound vehicles on approach to the HRBT southern tunnel, which carries Interstate 64 across the mouth of Hampton Roads.[19]

The island, now called Rip Raps, continues to settle, and occasionally the casemates of the original fortress are off-limits for safety reasons.[19]

See also

Notes

- On 28 April 2007, a garrison flag was raised over Fort Wool for the first time. This took place during a parade of tall ships sailing past the fort, part of the 400th anniversary celebrations of the settlement of Jamestown.

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ "Simon Bernard and America's Coastal Forts". National Park Service. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ Permanent Fortifications and Sea-Coast Defenses April 23, 1862. pp 330-345 37th Congress, 2nd Session Report No. 86. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ "Endicott board's report" (PDF). Coast Defense Study Group (CDSG). Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ "Fort Wool Armament" (PDF). p 212; CDSG. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- 1 2 "Fort Wool National Register Nomination" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ↑ See "Harbor Defenses of the United States of America" CDSG website Archived 2012-11-05 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ See "Third System Forts 1820-1867" CDSG website.

- 1 2 "The Chesapeake Bay: Avenue for Attack". George Mason University. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "American State Papers Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, from the first session of the sixteenth to the second session of the eighteenth congress, inclusive: Part V Military Affairs, Volume II p 431-524". United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ "Christopher Van Deventer Papers, 1799-1925". Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ "New York Bar, p 24" (PDF). Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ Freeman 1997, Chapter 7.

- 1 2 "Civil War anniversary stirs interest in Fort Wool". Daily Press, Hampton Roads, VA. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ "Frank Leslie Famous Leaders and Battle Scenes of the Civil War". USF Clip Art Gallery web site. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ "CSS Virginia (1862-1862), ex-USS Merrimack". U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Armament list". CDSG. Retrieved 20 December 2012. p 212

- 1 2 3 "Fort Wool Holds Spot In U.S. History". Daily Press Hampton Roads, VA. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

Bibliography

- Freeman, Douglas S. (1934). "R. E. Lee, A Biography". Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 2008-05-20.