Ethnic groups in Nepal

Ethnic groups in Nepal are a product of both the colonial and state-building eras of Nepal. The groups are delineated using language, ethnic identity or the caste system in Nepal. They are categorized by common culture and endogamy. Endogamy carves out ethnic groups in Nepal.

Linguistic groups

Nepal's diverse linguistic heritage evolved from three major language groups: Indo-Aryan, Tibeto-Burman languages, and various indigenous language isolates. According to the 2001 national census, ninety two different living languages are spoken in Nepal (a ninety third category was "unspecified"). Based upon the 2011 census, the major languages spoken in Nepal are Nepali and Nepal Bhasa, .[2]

Nepali (derived from Khas language) is considered to be a member of Indo-European language and is written in Devanagari script. Nepali was the language of the house of Gorkhas in the late 18th century and became the official, national language that serves as the lingua franca among Nepalese of different ethnolinguistic groups. Maithili—along with regional dialects Awadhi and Bhojpuri—are Indian languages and are spoken in the southern Terai Region.

Nepalese in the government sector and in business, use English as an official language. English is the language of the technical, medical, and scientific communities as well as for bankers, traders, and entrepreneurs. There has been a surge in the number and percentage of people who understand English. The majority of urban and a significant number of rural schools use English as a language of instruction. Higher education in technical, medical, scientific, and engineering fields are entirely in English.

Nepal Bhasa, the mother-tongue of the Newars, is widely used and spoken in and around Kathmandu Valley and in major Newar trade towns across Nepal.

Other languages, particularly in the Inner Terai hill and mountain regions, are remnants of the country's pre-unification history of dozens of political entities isolated by topography. These languages typically are limited to an area spanning about one day's walk. Beyond that distance, dialects and languages lose mutual intelligibility.

Since Nepal's unification, various indigenous languages have come under threat of extinction as the government of Nepal has marginalized their use through strict policies designed to promote Nepali as the official language. Indigenous languages which have gone extinct or are critically threatened include Byangsi, Chonkha, and Longaba. Since democracy was restored in 1990, however, the government has worked to improve the marginalization of these languages. Tribhuvan University began surveying and recording threatened languages in 2010 and the government intends to use this information to include more languages on the next Nepalese census.[3]

Social status

The Kirati people of Eastern Nepal and Limbus together with the Rais, form one of the largest single ethnic groups in Nepal.[4] Pahari Hill Hindus of the Khas Gorkha tribe (Bahun and Chhetri castes) and the Newar ethnicity dominated the civil service, the judiciary and upper ranks of the army throughout the Shah regime (1768–2008). Nepali was the national language and Sanskrit became a required school subject. Children who spoke Nepali natively and who were exposed to Sanskrit had much better chances of passing the national examinations at the end of high school, which meant they had better employment prospects and could continue into higher education.

On the other hand, children who natively spoke local languages of the Madhesh and Hills, or Tibetan dialects prevailing in the high mountains were at a considerable disadvantage. This history of exclusion coupled with poor prospects for improvement created grievances that encouraged many in ethnic communities such as Madhesi, Tharu and Kham Magar to support the Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) and various other armed Maoist opposition groups such as the JTMM during and after the Nepalese Civil War. The negotiated end to this war forced King Gyanendra to abdicate in 2008.

Issues of ethnic and regional equity have tended to dominate the agenda of the new republican government and continue to be divisive. Today, even after the end of a 10-year-old Maoist conflict, the upper caste dominates every field in Nepal. Specifically, Brahmin and Chhetri (Indo-Aryan) have advantages. Although Newars are low in numbers, their urban living habitat gives them a competitive advantage. Thus, Newars are at the top of the Human Development Index. From a gender perspective, Newari women are the most literate and lead in every sector. Brahmin and Chhetri women have experienced less social and economic mobility compared to Newari women. Specifically, Brahmin women experience less equality due to their predominately rural living conditions which deprives them of access to certain educational and healthcare benefits.[5][6][7][8][9]

Bahun and Chhetri castes form the historical topmost state elites' circle with the significant majority of leadership in executive, legislative, judicial, constitutional, local administrative bodies, bureaucracy, political parties and social organizations. Hindu varna system highlights these castes as high castes and makes them favorable in higher social status due to favorable social norms, values, and laws. [10]

List of ethnic groups in Nepal by population

The population wise ranking of 125 Nepalese castes/ethnic groups as per 2011 Nepal census.[11][note 1][12]

| Rank | Caste/Ethnic groups (2011 Nepal census) | Population | Percentage composition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kshetri/Chhetri | 4,398,053 | 16.60% | ||||

| 2 | Hill Brahmin/Bahun | 3,226,903 | 12.18% | ||||

| 3 | Magar | 1,887,733 | 7.12% | ||||

| 4 | Tharu | 1,737,470 | 6.56% | ||||

| 5 | Tamang | 1,539,830 | 5.81% | ||||

| 6 | Newar | 1,321,933 | 4.99% | ||||

| 7 | Kami | 1,258,554 | 4.75% | ||||

| 8 | Musalman/Nepali Muslims | 1,164,255 | 4.39% | ||||

| 9 | Yadav | 1,054,458 | 3.98% | ||||

| 10 | Rai | 620,004 | 2.34% | ||||

| 11 | Gurung | 522,641 | 1.97% | ||||

| 12 | Damai/Dholi | 472,862 | 1.78% | ||||

| 13 | Thakuri | 425,623 | 1.61% | ||||

| 14 | Limbu | 387,300 | 1.46% | ||||

| 15 | Sarki | 374,816 | 1.41% | ||||

| 16 | Teli | 369,688 | 1.40% | ||||

| 17 | Chamar/Harijan/Ram | 335,893 | 1.27% | ||||

| 18 | Koiri/Kushwaha | 306,393 | 1.16% | ||||

| 19 | Musahar | 234,490 | 0.89% | ||||

| 20 | Kurmi | 231,129 | 0.87% | ||||

| 21 | Sanyasi/Dasnami | 227,822 | 0.86% | ||||

| 22 | Dhanuk | 219,808 | 0.83% | ||||

| 23 | Kanu/Haluwai | 209,053 | 0.79% | 24 | Dusadh/Pasawan/Pasi | 208,910 | 0.79% |

| 25 | Mallaha | 173,261 | 0.65% | ||||

| 26 | Kewat | 153,772 | 0.58% | ||||

| 27 | Kathabaniyan | 138,637 | 0.52% | ||||

| 28 | Brahmin-Tarai (Maithil, Kanyakubja, Bengali) | 134,106 | 0.51% | ||||

| 29 | Kalwar | 128,232 | 0.48% | ||||

| 30 | Kumal | 121,196 | 0.46% | ||||

| 31 | Bhujel | 118,650 | 0.45% | ||||

| 32 | Hajam/Thakur | 117,758 | 0.44% | ||||

| 33 | Rajbanshi | 115,242 | 0.43% | ||||

| 34 | Sherpa | 112,946 | 0.43% | ||||

| 35 | Dhobi | 109,079 | 0.41% | ||||

| 36 | Tatma/Tatwa | 104,865 | 0.40% | ||||

| 37 | Lohar | 101,421 | 0.38% | ||||

| 38 | Khatwe | 100,921 | 0.38% | ||||

| 39 | Sudhi | 93,115 | 0.35% | ||||

| 40 | Danuwar | 84,115 | 0.32% | ||||

| 41 | Majhi | 83,727 | 0.32% | ||||

| 42 | Barai | 80,597 | 0.30% | ||||

| 43 | Bin | 75,195 | 0.28% | ||||

| 44 | Nuniya | 70,540 | 0.27% | ||||

| 45 | Chepang | 68,399 | 0.26% | ||||

| 46 | Sonar | 64,335 | 0.24% | ||||

| 47 | Kumhar | 62,399 | 0.24% | ||||

| 48 | Sunwar | 55,712 | 0.21% | ||||

| 49 | Bantar/Sardar | 55,104 | 0.21% | ||||

| 50 | Kahar | 53,159 | 0.20% | ||||

| 51 | Santhal | 51,735 | 0.20% | ||||

| 52 | Marwadi | 51,443 | 0.19% | ||||

| 53 | Kayastha | 44,304 | 0.17% | ||||

| 54 | Rajput/Terai Kshetriya | 41,972 | 0.16% | ||||

| 55 | Badi | 38,603 | 0.15% | ||||

| 56 | Jhangar/Uraon | 37,424 | 0.14% | ||||

| 57 | Gangai | 36,988 | 0.14% | ||||

| 58 | Lodh | 32,837 | 0.12% | ||||

| 59 | Badhaee | 28,932 | 0.11% | ||||

| 60 | Thami | 28,671 | 0.11% | ||||

| 61 | Kulung | 28,613 | 0.11% | ||||

| 63 | Bengali | 26,582 | 0.10% | ||||

| 123 | Raute | 618 | 0.00% | ||||

| 124 | Nurang | 278 | 0.00% | ||||

| 125 | Kusunda | 273 | 0.00% | ||||

| - | Others undefined and foreigners | 282,321 | 1.07% | ||||

| - | Total | 26,494,504 | 100.00% |

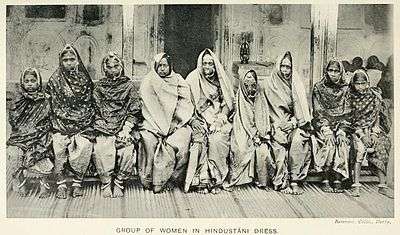

Gallery

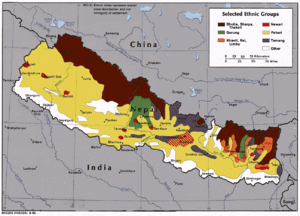

Map showing broad ethnic groups in Nepal

Map showing broad ethnic groups in Nepal Sunuwar Kirat girl 19th century

Sunuwar Kirat girl 19th century- Traditional Bahun priest at Kathmandu

Tharu women

Tharu women Teej celebrated by women of Khas community

Teej celebrated by women of Khas community Banras/Shakya Buddhist priests of Newar group

Banras/Shakya Buddhist priests of Newar group a Khas Jhakri shaman

a Khas Jhakri shaman Damai men playing Damaha

Damai men playing Damaha Children from isolated Danuwar ethnolinguistic group

Children from isolated Danuwar ethnolinguistic group- Tamang women

Limbu aboriginal group

Limbu aboriginal group Tharu women

Tharu women Limbu traditional chyabrung. Ilam, Nepal

Limbu traditional chyabrung. Ilam, Nepal Newar group

Newar group.jpg) Procession of Khas Parbattia Wedding

Procession of Khas Parbattia Wedding Sherpa, upper Tibetic ethnic group

Sherpa, upper Tibetic ethnic group Kirati Limbu women performing Kelang

Kirati Limbu women performing Kelang Magar man, military tribe, Nepal

Magar man, military tribe, Nepal Senior offering Dashain Tika; a feature of Khas Parbattia community

Senior offering Dashain Tika; a feature of Khas Parbattia community Raute man; Rautes are below 1000

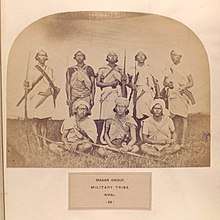

Raute man; Rautes are below 1000 Magar group, military tribe, Nepal

Magar group, military tribe, Nepal Khas man of Nepal, as depicted in The People of India (1868-1875)

Khas man of Nepal, as depicted in The People of India (1868-1875) Kurmi women

Kurmi women Magars

Magars

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Pages 191/192 of the total pdf or pages 156/157 in the scanned material shows Nepalese castes/ethnic groups

Notes

- ↑ "South Asia ::NEPAL". CIA The World Factbook.

- ↑ "Official Summary of Census" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics, Nepal. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012.

- ↑ Tumbahang, Govinda Bahadur (2010). "Marginalization of indigenous languages of Nepal". Contributions to Nepalese Studies. 37: 69 – via Expanded Academic.

- ↑ Researches Into the History and Civilization of the Kirātas By G. P. Singh, Gyan Publishing House, 2008

- ↑ "OCHA Nepal – Situation Overview" (PDF). Issue 12. OCHA. April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ "OCHA Nepal – Situation Overview" (PDF). Issue 16. OCHA. July–August 2007. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ "OCHA Nepal – Situation Overview" (PDF). Issue 30. OCHA. June–July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ Sharma, Hari (2010-11-18). "Body of murder victim found in Gulmi". Gulmi: The Himalayan Times online. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ Hatlebakk, Magnus (2007). "Economic and social structures that may explain the recent conflicts in the Terai of Nepal" (PDF). Kathmandu: Norwegian Embassy. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ↑ http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/printedition/news/2016-04-05/caste-of-characters.html

- ↑ http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf

- ↑ "Nepal Census 2011" (PDF).