Demographics of South Korea

This article is about the demographic features of the population of South Korea, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

In June 2012, South Korea's population reached 50 million.[1] Since the 2000s, South Korea has been struggling with a low birthrate, leading some researchers to suggest that if current population trends hold, the country's population will shrink to approximately 38 million population towards the end of the 21st century[2] In 2016, South Korea's population was 51.25 million people.[3]

Background

In South Korea, a variety of different Asian people had migrated to the Korean Peninsula in past centuries, however few have remain permanent. South Korea and North Korea are among the world's most ethnically homogenous nations. Both North Korea and South Korea equate nationality or citizenship with membership in a single, homogenous ethnic group and politicized notion of "race."

The common language and especially race are viewed as important elements by South Koreans in terms of identity, more than citizenship.

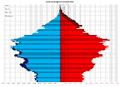

Population trends

Population of South Korea by age and sex (demographic pyramid)

as on 1955-09-01

as on 1955-09-01 as on 1960-11-01

as on 1960-11-01 as on 1965-11-01

as on 1965-11-01 as on 1970-10-01

as on 1970-10-01 as on 1975-11-01

as on 1975-11-01 as on 1980-11-01

as on 1980-11-01 as on 1985-11-01

as on 1985-11-01 as on 1990-11-01

as on 1990-11-01 as on 1995-11-01

as on 1995-11-01 as on 2000-11-01

as on 2000-11-01 as on 2005-11-01

as on 2005-11-01 as on 2010-11-01

as on 2010-11-01 as on 2015-11-01

as on 2015-11-01.png) Live births, deaths of South Korea (1925~2016)

Live births, deaths of South Korea (1925~2016).png) Crude births, deaths rate of South Korea (1925~2016)

Crude births, deaths rate of South Korea (1925~2016)

According to Worldometers' South Korea Population Forecast statistics, South Korea is supposed to have a .36% yearly change increase by 2020, a .28% yearly change increase by 2025, a .18% yearly change increase by 52,701,817, and a .04% yearly change increase by 2035.[4] According to those same statistics, the years from 2040 to 2050 are supposed to have a steady decline of yearly change percentages.[4]

The population of South Korea showed robust growth since the republic's establishment in 1948, and then dramatically slowed down with the effects of its economic growth. In the first official census, taken in 1949, the total population of South Korea was calculated at 20,188,641 people. The 1985 census total was 40,466,577. Population growth was slow, averaging about 1.1% annually during the period from 1949 to 1955, when the population registered at 21.5 million. Growth accelerated between 1955 and 1966 to 29.2 million or an annual average of 2.8%, but declined significantly during the period 1966 to 1985 to an annual average of 1.7%. Thereafter, the annual average growth rate was estimated to be less than 1%, similar to the low growth rates of most industrialized countries and to the target figure set by the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs for the 1990s. As of January 1, 1989, the population of South Korea was estimated to be approximately 42.2 million.

The proportion of the total population under fifteen years of age has risen and fallen with the growth rate. In 1955 approximately 41.2% of the population was under fifteen years of age, a percentage that rose to 43.5% in 1966 before falling to 38.3% in 1975, 34.2% in 1980, and 29.9% in 1985. In the past, the large proportion of children relative to the total population put great strains on the country's economy, particularly because substantial resources were invested in education facilities. With the slowdown in the population growth rate and a rise in the median age (from 18.7 years to 21.8 years between 1960 and 1980), the age structure of the population has begun to resemble the columnar pattern typical of developed countries, rather than the pyramidal pattern found in most parts of the Third World.

The decline in the population growth rate and in the proportion of people under fifteen years of age after 1966 reflected the success of official and unofficial birth control programs. The government of President Syngman Rhee (1948–60) was conservative in such matters. Although Christian churches initiated a family planning campaign in 1957, it was not until 1962 that the government of Park Chung Hee, alarmed at the way in which the rapidly increasing population was undermining economic growth, began a nationwide family planning program. Other factors that contributed to a slowdown in population growth included urbanization, later marriage ages for both men and women, higher education levels, a greater number of women in the labor force, and better health standards.

Public and private agencies involved in family planning included the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Planned Parenthood Federation of Korea, and the Korea Institute of Family Planning. In the late 1980s, their activities included distribution of free birth control devices and information, classes for women on family planning methods, and the granting of special subsidies and privileges (such as low-interest housing loans) to parents who agreed to undergo sterilization. There were 502,000 South Koreans sterilized in 1984, as compared with 426,000 in the previous year.[5]

The 1973 Maternal and Child Health Law legalized abortion. In 1983 the government began suspending medical insurance benefits for maternal care for pregnant women with three or more children. It also denied tax deductions for education expenses to parents with two or more children.

As in China, cultural attitudes posed problems for family planning programs. A strong preference for sons—who in Korea's traditional Confucian value system are expected to care for their parents in old age and carry on the family name—means that parents with only daughters usually continued to have children until a son is born. The government encouraged married couples to have only one child. This has been a prominent theme in public service advertising, which stresses "have a single child and raise it well."

Total fertility rates (the average number of births a woman will have during her lifetime) fell from 6.1 births per female in 1960 to 4.2 in 1970, 2.8 in 1980, and 2.4 in 1984. The number of live births, recorded as 711,810 in 1978, grew to a high of 917,860 in 1982. This development stirred apprehensions among family planning experts of a new "baby boom." By 1986, however, the number of live births had declined to 806,041.

Decline in population growth continued, and between 2005 and 2010 total fertility rate for South Korean women was 1.21, one of the world's lowest according to the United Nations.[6] Fertility rate well below the replacement level of 2.1 births per female has triggered a national alarm, with dire predictions of an aging society unable to grow or support its elderly. Recent Korean governments have prioritized the issue on its agenda, promising to enact social reforms that will encourage women to have children.

The country's population increased to 46 million by the end of the twentieth century, with growth rates ranging between 0.9% and 1.2%. The population is expected to stabilize (that is, cease to grow) in the year 2023 at around 52.6 million people. In the words of Asiaweek magazine, the "stabilized tally will approximate the number of Filipinos in 1983, but squeezed into less than a third of their [the Philippines'] space."

Population settlement patterns

South Korea is one of the world's most densely populated countries, with an estimated 425 people per square kilometer in 1989—over sixteen times the average population density of the United States in the late 1980s.[7] By comparison, China had an estimated 114 people, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) 246 people, and Japan 323 people per square kilometer in the late 1980s. Because about 70% of South Korea's land area is mountainous and the population is concentrated in the lowland areas, actual population densities were in general greater than the average. As early as 1975, it was estimated that the density of South Korea's thirty-five cities, each of which had a population of 50,000 or more inhabitants, was 3,700 people per square kilometer. Because of continued migration to urban areas, the figure was doubtless higher in the late 1980s.

In 1988 Seoul had a population density of 17,030 people per square kilometer as compared with 13,816 people per square kilometer in 1980. The second largest city, Busan, had a density of 8,504 people per square kilometer in 1988 as compared with 7,272 people in 1980. Kyonggi Province, which surrounds the capital and contains Inch'on, the country's fourth largest city, was the most densely populated province; Kangwon Province in the northeast was the least densely populated province.

According to the government's Economic Planning Board, the population density will be 530 people per square kilometer by 2023, the year the population is expected to stabilize.

Rural areas in South Korea consist of agglomerated villages in river valleys and range from a few houses to several hundred.[8] These villages are located in the south that are backed by hills and give strong protection from winter winds.[8]

Since 1960, the pace of urbanization in South Korea has hit a considerable decline in population of rural areas and the traditional rural lifestyle has been slowly fading away.[8]

Aging population

South Korea faces the problem of a rapidly aging population. In fact, the speed of aging in Korea is unprecedented in human history,[9] 18 years to double aging population from 7 – 14% (least number of years),[10] overtaking even Japan. Statistics support this observation, the percentage of elderly aged 65 and above, has sharply risen from 3.3% in 1955 to 10.7% in 2009.[11] The shape of its population has changed from a pyramid in the 1990s, with more young people and fewer old people, to a diamond shape in 2010, with less young people and a large proportion of middle-age individuals.[12]

There are several implications and issues associated with an aging population. A rapidly aging population is likely to have several negative implications on the labour force. In particular, experts predict that this might lead to a shrinking of the labour force. As an increasing proportion of people enter their 50s and 60s, they either choose to retire or are forced to retire by their companies. As such, there would be a decrease in the percentage of economically active people in the population. Also, with rapid aging, it is highly likely that there would be an imbalance in the young-old percentage of the workforce. This might lead to a lack of vibrancy and innovation in the labour force, since it is helmed mainly by the middle-age workers. Data shows that while there are fewer young people in society, the percentage of economically active population, made up of people ages 15 – 64, has gone up by 20% from 55.5% to 72.5%.[11] This shows that the labour force is indeed largely made up of middle-aged workers.

A possible consequence might be that South Korea would be a less attractive candidate for investment. Investors might decide to relocate to countries like Vietnam and China, where there is an abundance of cheaper, younger labour. If employers were to choose to maintain operations in South Korea, there is a possibility that they might incur higher costs in retraining or upgrading the skills of this group of middle-age workers. On top of that, higher healthcare costs might also be incurred [13] and the government would need to set aside more money to maintain a good healthcare system to cater to the elderly.

Due to the very low birth rate, South Korea is predicted to enter a Russian Cross pattern once the large generation born in the 1960s starts to die off, with potentially decades of population decline.

Urbanization

Like other newly industrializing economies, South Korea experienced rapid growth of urban areas caused by the migration of large numbers of people from the countryside. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Seoul, by far the largest urban settlement, had a population of about 190,000 people. There was a striking contrast with Japan, where Edo (Tokyo) had as many as 1 million inhabitants and the urban population comprised as much as 10% to 15% of the total during the Tokugawa Period (1600–1868). During the closing years of the Choson Dynasty and the first years of Japanese colonial rule, the urban population of Korea was no more than 3% of the total. After 1930, when the Japanese began industrial development on the Korean Peninsula, particularly in the northern provinces adjacent to Manchuria, the urban portion of the population began to grow, reaching 11.6% for all of Korea in 1940.

Between 1945 and 1985, the urban population of South Korea grew from 14.5% to 65.4% of the total population. In 1988 the Economic Planning Board estimated that the urban portion of the population will reach 78.3% by the end of the twentieth century. Most of this urban increase was attributable to migration rather than to natural growth of the urban population. Urban birth rates have generally been lower than the national average. The extent of urbanization in South Korea, however, is not fully revealed in these statistics. Urban population was defined in the national census as being restricted to those municipalities with 50,000 or more inhabitants. Although many settlements with fewer than 50,000 inhabitants were satellite towns of Seoul or other large cities or mining communities in northeastern Kangwon Province, which would be considered urban in terms of the living conditions and occupations of the inhabitants, they still were officially classified as rural.

The dislocation caused by the Korean War accounted for the rapid increase in urban population during the early 1950s. Hundreds of thousands of refugees, many of them from North Korea, streamed into the cities. During the post-Korean War period, rural people left their ancestral villages in search of greater economic and educational opportunities in the cities. By the late 1960s, migration had become a serious problem, not only because cities were terribly overcrowded, but also because the rural areas were losing the most youthful and productive members of their labor force.

In 1970, the Park Chung Hee government launched the Saemaul Undong (New Community Movement) as a rural reconstruction and self-help movement to improve economic conditions in the villages, close the wide gap in income between rural and urban areas, and stem urban migration—as well as to build a political base. Despite a huge amount of government sponsored publicity, especially during the Park era, it was not clear by the late 1980s that the Saemaul undong had achieved its objectives. By that time many, if not most, farming and fishing villages consisted of older persons; relatively few able-bodied men and women remained to work in the fields or to fish. This trend was apparent in government statistics for the 1986–87 period: the proportion of people fifty years old or older living in farming communities grew from 28.7% in 1986 to 30.6% in 1987, while the number of people in their twenties living in farming communities declined from 11.3% to 10.8%. The nationwide percentages for people fifty years old or older and in their twenties were, in 1986, 14.9% and 20.2%, respectively (see Agriculture, ch. 3).

In 1985 the largest cities were Seoul (9,645,932 inhabitants), Busan (3,516,807), Daegu (2,030,672), Incheon (1,387,491), Gwangju (906,129), and Daejeon (866,695). According to government statistics, the population of Seoul, one of the world's largest cities, surpassed 10 million people in late 1988. Seoul's average annual population growth rate during the late 1980s was more than 3%. Two-thirds of this growth was attributable to migration rather than to natural increase. Surveys revealed that "new employment or seeking a new job," "job transfer," and "business" were major reasons given by new immigrants for coming to the capital. Other factors cited by immigrants included "education" and "a more convenient area to live."

To alleviate overcrowding in Seoul's downtown area, the city government drew up a master plan in the mid-1980s that envisioned the development of four "core zones" by 2000: the original downtown area, Yongdongpo-Yeouido, Yongdong, and Jamsil. Satellite towns also would be established or expanded. In the late 1980s, statistics revealed that the daytime or commuter population of downtown Seoul was as much as six times the officially registered population. If the master plan is successful, many commuters will travel to work in a core area nearer their homes, and the downtown area's daytime population will decrease. Many government ministries have been moved out of Seoul, and the army, navy, and air force headquarters have been relocated to Daejeon.

In 1985 the population of Seoul constituted 23.8% of the national total. Provincial cities, however, experienced equal and, in many cases, greater expansion than the capital. Growth was particularly spectacular in the southeastern coastal region, which encompasses the port cities of Busan, Masan, Yosu, Chinhae, Ulsan, and Pohang. Census figures show that Ulsan's population increased eighteenfold, growing from 30,000 to 551,300 inhabitants between 1960 and 1985. With the exception of Yosu, all of these cities are in South Kyongsang Province, a region that has been an especially favored recipient of government development projects. By comparison, the population of Kwangju, capital of South Cholla Province, increased less than threefold between 1960 and 1985, growing from 315,000 to 906,129 inhabitants.

Rapid urban growth has brought familiar problems to developed and developing countries alike. The construction of large numbers of high-rise apartment complexes in Seoul and other large cities alleviated housing shortages to some extent. But it also imposed hardship on the tens of thousands of people who were obliged to relocate from their old neighborhoods because they could not afford the rents in the new buildings. In the late 1980s, squatter areas consisting of one-story shacks still existed in some parts of Seoul. Housing for all but the wealthiest was generally cramped. The concentration of factories in urban areas, the rapid growth of motorized traffic, and the widespread use of coal for heating during the severe winter months caused dangerous levels of air and water pollution, issues that still persist today even after years of environmentally friendly policies.

Like other newly industrializing economies, South Korea experienced rapid growth of urban areas caused by the migration of large numbers of people from the countryside. In 2016, 82.59 percent of South Korea's total population lived in urban areas and cities.[14]

Vital statistics

UN estimates

Source:[15]

| Period | Live births per year | Deaths per year | Natural change per year | CBR1 | CDR1 | NC1 | TFR1 | IMR1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 722,000 | 331,000 | 391,000 | 35.8 | 16.4 | 19.4 | 5.05 | 138.0 |

| 1955–1960 | 1,049,000 | 356,000 | 693,000 | 45.4 | 15.4 | 30.0 | 6.33 | 114.4 |

| 1960–1965 | 1,067,000 | 347,000 | 720,000 | 39.9 | 13.0 | 27.0 | 5.63 | 89.7 |

| 1965–1970 | 985,000 | 298,000 | 687,000 | 32.9 | 9.9 | 23.0 | 4.71 | 64.2 |

| 1970–1975 | 1,004,000 | 259,000 | 746,000 | 30.4 | 7.8 | 22.5 | 4.28 | 38.1 |

| 1975–1980 | 833,000 | 253,000 | 581,000 | 23.1 | 7.0 | 16.1 | 2.92 | 33.2 |

| 1980–1985 | 795,000 | 248,000 | 547,000 | 20.4 | 6.4 | 14.0 | 2.23 | 24.6 |

| 1985–1990 | 647,000 | 239,000 | 407,000 | 15.5 | 5.7 | 9.8 | 1.60 | 14.9 |

| 1990–1995 | 702,000 | 239,000 | 463,000 | 16.0 | 5.5 | 10.6 | 1.70 | 9.7 |

| 1995–2000 | 615,000 | 247,000 | 368,000 | 13.6 | 5.5 | 8.1 | 1.51 | 6.6 |

| 2000–2005 | 476,000 | 245,000 | 231,000 | 10.2 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 1.22 | 5.3 |

| 2005–2010 | 477,000 | 243,000 | 234,000 | 10.0 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 1.29 | 3.8 |

| 2010–2015 | 455,000 | 275,000 | 180,000 | 1.26 | ||||

| 1 CBR = crude birth rate (per 1000); CDR = crude death rate (per 1000); NC = natural change (per 1000); TFR = total fertility rate (number of children per woman); IMR = infant mortality rate per 1000 births | ||||||||

Life expectancy at birth from 1908 to 2015

Sources: Our World In Data and the United Nations.

1865-1949

| Years | 1908 | 1913 | 1918 | 1923 | 1928 | 1933 | 1938 | 1942 | 1950[16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy in South Korea | 23.5 | 25.0 | 27.0 | 29.5 | 33.6 | 37.4 | 42.6 | 44.9 | 46.7 |

1950-2015

| Period | Life expectancy in Years |

Period | Life expectancy in Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 47.9 | 1985–1990 | 70.3 |

| 1955–1960 | 51.2 | 1990–1995 | 72.9 |

| 1960–1965 | 54.8 | 1995–2000 | 75.0 |

| 1965–1970 | 58.8 | 2000–2005 | 77.2 |

| 1970–1975 | 63.1 | 2005–2010 | 79.4 |

| 1975–1980 | 65.0 | 2010–2015 | 81.3 |

| 1980–1985 | 67.4 |

Source: UN World Population Prospects[17]

Total Fertility Rate from 1900 to 1924

The total fertility rate is the number of children born per woman. It is based on fairly good data for the entire period. Sources: Our World In Data and Gapminder Foundation.[18]

| Years | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910[18] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fertility Rate in South Korea | 6 | 6 | 5.99 | 5.99 | 5.98 | 5.98 | 5.97 | 5.96 | 5.96 | 5.96 |

| Years | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920[18] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fertility Rate in South Korea | 5.95 | 5.95 | 5.94 | 5.94 | 5.93 | 5.93 | 5.92 | 5.92 | 5.93 | 5.94 |

| Years | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924[18] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fertility Rate in South Korea | 5.95 | 5.96 | 5.97 | 5.95 |

Registered births and deaths

Source:[15]

| Average population | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | Total fertility rate (TFR)[18] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 12,997,611 | 558,897 | 359,042 | 199,855 | 43.0 | 27.6 | 15.4 | 5.95 |

| 1926 | 13,052,741 | 511,667 | 337,948 | 173,719 | 39.2 | 25.9 | 13.3 | 5.91 |

| 1927 | 13,037,169 | 534,524 | 353,818 | 180,706 | 41.0 | 27.1 | 13.9 | 5.89 |

| 1928 | 13,105,131 | 566,142 | 357,701 | 208,441 | 43.2 | 27.3 | 15.9 | 5.87 |

| 1929 | 13,124,279 | 566,969 | 414,366 | 152,603 | 43.2 | 31.6 | 11.6 | 5.9 |

| 1930 | 13,880,469 | 587,144 | 322,611 | 264,533 | 42.3 | 23.2 | 19.1 | 5.93 |

| 1931 | 13,895,052 | 589,428 | 346,800 | 242,628 | 42.4 | 25.0 | 17.4 | 5.96 |

| 1932 | 14,117,191 | 600,545 | 384,287 | 216,258 | 42.5 | 27.2 | 15.3 | 5.99 |

| 1933 | 14,229,277 | 607,021 | 336,232 | 270,789 | 42.7 | 23.6 | 19.1 | 6.02 |

| 1934 | 14,449,155 | 618,135 | 356,515 | 261,620 | 42.8 | 24.7 | 18.1 | 6.05 |

| 1935 | 15,061,960 | 646,158 | 377,454 | 268,704 | 42.9 | 25.1 | 17.8 | 6.08 |

| 1936 | 15,114,775 | 639,355 | 381,806 | 257,549 | 42.3 | 25.3 | 17.0 | 6.12 |

| 1937 | 15,235,383 | 636,839 | 342,575 | 294,264 | 41.8 | 22.5 | 19.3 | 6.15 |

| 1938 | 15,358,193 | 569,299 | 347,025 | 222,274 | 37.1 | 22.6 | 14.5 | 6.18 |

| 1939 | 15,486,028 | 585,482 | 353,391 | 232,091 | 37.8 | 22.8 | 15.0 | 6.16 |

| 1940 | 15,559,741 | 527,964 | 358,496 | 169,468 | 33.9 | 23.0 | 10.9 | 6.14 |

| 1941 | 15,745,478 | 553,690 | 366,239 | 187,451 | 35.2 | 23.3 | 11.9 | 6.12 |

| 1942 | 16,013,742 | 533,768 | 376,003 | 157,765 | 33.3 | 23.5 | 9.8 | 6.1 |

| 1943 | 16,239,721 | 513,846 | 384,881 | 128,965 | 31.6 | 23.7 | 7.9 | 6.08 |

| 1944 | 16,599,172 | 533,215 | 380,121 | 153,094 | 32.1 | 22.9 | 9.2 | 5.98 |

| 1945 | 16,695,819 | 544,786 | 367,308 | 177,478 | 32.6 | 22.0 | 10.6 | 5.88 |

| 1946 | 19,369,270 | 590,763 | 410,629 | 180,134 | 30.5 | 21.2 | 9.3 | 5.79 |

| 1947 | 19,836,234 | 686,334 | 361,019 | 325,315 | 35.0 | 18.2 | 16.8 | 5.69 |

| 1948 | 20,027,393 | 692,948 | 374,512 | 318,436 | 34.6 | 18.7 | 15.9 | 5.59 |

| 1949 | 20,188,641 | 696,508 | 341,188 | 355,320 | 34.5 | 16.9 | 17.6 | 4.81 |

| 1950 | 19,211,386 | 633,976 | 597,474 | 36,502 | 33.0 | 31.1 | 1.9 | 5.05 |

| 1951 | 19,304,737 | 675,666 | 579,142 | 96,524 | 35.0 | 30.0 | 5.0 | |

| 1952 | 19,566,860 | 722,018 | 457,865 | 264,153 | 36.9 | 23.4 | 13.5 | |

| 1953 | 19,979,069 | 777,186 | 363,619 | 413,567 | 38.9 | 18.2 | 20.7 | |

| 1954 | 20,520,601 | 839,293 | 348,850 | 490,433 | 40.9 | 17.0 | 23.9 | |

| 1955 | 21,168,611 | 908,134 | 295,302 | 612,832 | 42.9 | 14.0 | 28.9 | 6.33 |

| 1956 | 21,897,911 | 945,990 | 294,344 | 651,646 | 43.2 | 13.4 | 29.8 | |

| 1957 | 22,681,233 | 963,952 | 293,344 | 670,608 | 42.5 | 12.9 | 29.6 | |

| 1958 | 23,490,027 | 993,628 | 291,864 | 701,764 | 42.3 | 12.4 | 29.9 | |

| 1959 | 24,295,786 | 1,016,173 | 289,525 | 726,648 | 41.8 | 11.9 | 29.9 | |

| 1960 | 25,012,374 | 1,080,535 | 285,350 | 795,185 | 43.2 | 11.4 | 31.8 | 6.16 |

| 1961 | 25,765,673 | 1,046,086 | 280,846 | 765,240 | 40.6 | 10.9 | 29.7 | 5.99 |

| 1962 | 26,513,030 | 1,036,659 | 270,433 | 760,266 | 39.1 | 10.2 | 28.9 | 5.79 |

| 1963 | 27,261,747 | 1,033,220 | 278,070 | 755,150 | 37.9 | 10.2 | 27.7 | 5.57 |

| 1964 | 27,984,155 | 1,001,833 | 279,842 | 721,991 | 35.8 | 10.0 | 25.8 | 5.36 |

| 1965 | 28,704,674 | 996,052 | 272,694 | 723,358 | 34.7 | 9.5 | 25.2 | 5.16 |

| 1966 | 29,435,571 | 1,030,245 | 294,356 | 735,889 | 35.0 | 10.0 | 25.0 | 4.99 |

| 1967 | 30,130,983 | 1,005,293 | 242,280 | 763,013 | 33.4 | 8.0 | 25.4 | 4.84 |

| 1968 | 30,838,302 | 1,043,321 | 280,308 | 763,013 | 33.8 | 9.1 | 24.7 | 4.72 |

| 1969 | 31,544,266 | 1,044,943 | 270,023 | 774,920 | 33.1 | 8.6 | 24.5 | 4.62 |

| 1970 | 32,240,827 | 1,006,645 | 258,589 | 748,056 | 31.2 | 8.0 | 23.2 | 4.53 |

| 1971 | 32,882,704 | 1,024,773 | 237,528 | 787,245 | 31.2 | 7.2 | 23.9 | 4.54 |

| 1972 | 33,505,406 | 952,780 | 210,071 | 742,709 | 28.4 | 6.3 | 22.2 | 4.12 |

| 1973 | 34,103,149 | 965,521 | 267,460 | 698,061 | 28.3 | 7.8 | 20.5 | 4.07 |

| 1974 | 34,692,266 | 922,823 | 248,807 | 674,016 | 26.6 | 7.2 | 19.4 | 3.77 |

| 1975 | 35,280,725 | 874,030 | 270,657 | 603,373 | 24.8 | 7.7 | 17.1 | 3.43 |

| 1976 | 35,848,523 | 796,331 | 266,857 | 529,474 | 22.2 | 7.4 | 14.8 | 3.00 |

| 1977 | 36,411,795 | 825,339 | 249,254 | 576,085 | 22.7 | 6.8 | 15.8 | 2.99 |

| 1978 | 36,969,185 | 750,728 | 252,298 | 498,430 | 20.3 | 6.8 | 13.5 | 2.64 |

| 1979 | 37,534,236 | 862,669 | 239,986 | 622,683 | 23.0 | 6.4 | 16.6 | 2.90 |

| 1980 | 38,123,775 | 862,835 | 277,284 | 585,551 | 22.6 | 7.3 | 15.4 | 2.82 |

| 1981 | 38,723,248 | 867,409 | 237,481 | 629,928 | 22.4 | 6.1 | 16.3 | 2.57 |

| 1982 | 39,326,352 | 848,312 | 245,767 | 602,545 | 21.6 | 6.2 | 15.3 | 2.39 |

| 1983 | 39,910,403 | 769,155 | 254,563 | 514,592 | 19.3 | 6.4 | 12.9 | 2.06 |

| 1984 | 40,405,956 | 674,793 | 236,445 | 438,348 | 16.7 | 5.9 | 10.8 | 1.74 |

| 1985 | 40,805,744 | 655,489 | 240,418 | 415,071 | 16.1 | 5.9 | 10.2 | 1.66 |

| 1986 | 41,213,674 | 636,019 | 239,256 | 396,763 | 15.4 | 5.8 | 9.6 | 1.58 |

| 1987 | 41,621,690 | 623,831 | 243,504 | 380,327 | 15.0 | 5.9 | 9.1 | 1.53 |

| 1988 | 42,031,247 | 633,092 | 235,779 | 397,313 | 15.1 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 1.55 |

| 1989 | 42,449,038 | 639,431 | 236,818 | 402,613 | 15.1 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 1.56 |

| 1990 | 42,869,283 | 649,738 | 241,616 | 408,122 | 15.2 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 1.57 |

| 1991 | 43,295,704 | 709,275 | 242,270 | 467,005 | 16.4 | 5.6 | 10.8 | 1.71 |

| 1992 | 43,747,962 | 730,678 | 236,162 | 494,516 | 16.7 | 5.4 | 11.3 | 1.76 |

| 1993 | 44,194,628 | 715,826 | 234,257 | 481,569 | 16.0 | 5.2 | 10.8 | 1.65 |

| 1994 | 44,641,540 | 721,185 | 242,439 | 478,746 | 16.0 | 5.4 | 10.6 | 1.66 |

| 1995 | 45,092,991 | 715,020 | 242,838 | 472,182 | 15.7 | 5.3 | 10.3 | 1.63 |

| 1996 | 45,524,681 | 691,226 | 241,149 | 450,077 | 15.0 | 5.2 | 9.8 | 1.57 |

| 1997 | 45,953,580 | 668,344 | 241,943 | 426,401 | 14.4 | 5.2 | 9.2 | 1.52 |

| 1998 | 46,286,503 | 634,790 | 243,193 | 391,597 | 13.6 | 5.2 | 8.4 | 1.45 |

| 1999 | 46,616,677 | 614,233 | 245,364 | 368,869 | 13.0 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 1.41 |

| 2000 | 47,008,111 | 634,501 | 246,163 | 388,838 | 13.3 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 1.47 |

| 2001 | 47,370,164 | 554,895 | 241,521 | 313,374 | 11.6 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 1.30 |

| 2002 | 47,644,736 | 492,111 | 245,317 | 246,794 | 10.2 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 1.17 |

| 2003 | 47,892,330 | 490,543 | 244,506 | 246,037 | 10.2 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 1.18 |

| 2004 | 48,082,519 | 472,761 | 244,217 | 228,544 | 9.8 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 1.15 |

| 2005 | 48,184,561 | 435,031 | 243,883 | 191,148 | 8.9 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 1.08 |

| 2006 | 48,438,292 | 448,153 | 242,266 | 205,887 | 9.2 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 1.12 |

| 2007 | 48,683,638 | 493,189 | 244,874 | 248,315 | 10.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 1.25 |

| 2008 | 49,054,708 | 465,892 | 246,113 | 219,779 | 9.4 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 1.19 |

| 2009 | 49,307,835 | 444,849 | 246,942 | 197,907 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 1.15 |

| 2010 | 49,554,112 | 470,171 | 255,405 | 214,766 | 9.4 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 1.23 |

| 2011 | 49,936,638 | 471,265 | 257,396 | 213,869 | 9.4 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 1.24 |

| 2012 | 50,199,853 | 484,550 | 267,221 | 217,329 | 9.6 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 1.30 |

| 2013 | 50,428,893 | 436,455 | 266,257 | 170,198 | 8.6 | 5.3 | 3.4 | 1.19 |

| 2014 | 50,746,659 | 435,435 | 267,692 | 167,743 | 8.6 | 5.3 | 3.3 | 1.21 |

| 2015 | 51,014,947 | 438,420 | 275,895 | 162,525 | 8.6 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 1.24 |

| 2016 | 51,245,707 | 406,243 | 280,827 | 125,416 | 7.9 | 5.5 | 2.4 | 1.17 |

| 2017 | 51,446,201 | 357,800 | 285,600 | 72,200 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 1.05 |

Current natural population growth

- Births from January–July 2017 =

- Births from January–July 2018 =

- Deaths from January–July 2017 =

- Deaths from January–July 2018 =

- Natural growth from January–July 2017 =

- Natural growth from January–July 2018 =

Ethnic groups

South Korea is a relatively homogeneous society with an absolute majority of the population of Korean ethnicity who account for approximately 96% of the total population of the Korean Republic). However, with its emergence as an economic powerhouse, opportunities for foreign immigrants increased and in 2007 the number of foreign citizens resident in South Korea passed the million mark for the first time in history,[20] and the number reached 2 million in 2016. 1,016,000 of them came from China, with more than half of them being ethnic Koreans of Chinese citizenship. The next largest group was from Vietnam with 149,000 residents. The third largest group was from the United States with 117,000 residents, excluding the American troops stationed in the country. Thailand, Philippines, Uzbekistan and other countries followed.

Chinese in South Korea

When the People's Republic of China and South Korea reformed relationship was settled in, several Chinese migrants had emerged in South Korea in 1992.[21] In the early 1900s, a trade agreement allowed merchants from China conduct business trades in South Korea.[21]

North Americans in South Korea

South Korea's immigration rules are especially strict for non-Asians.[21] The South Koreans place various regulations on individuals applying for citizenship via marriage with one required to pass a Korean language proficiency test and have an annual income more than 14 million wons.[21] Due to this fact, most North Americans come to the country either as tourists or professionals.[21]

Vietnamese in South Korea

The relationship between Vietnamese and South Koreans goes back to the year 1200 when Ly Duong had left to Goreyeo in Korea after a succession of power dispute. Nowadays, Vietnamese migrants that go to South Korea are introduced to local husbands via marriage agencies.[21]

Filipinos in South Korea

The relationship between Filipinos and South Koreans can be traced back to the 1950s during the Korean war.[21] Over 7,500 Filipino soldiers fought on the United Nations' side to assist South Korea's conflict with North Korea.[21] During 2007, there was estimated to be around 70,000 Filipino immigrants in South Korea.[21] The mass rural urban migration led to a shortage of young women in those areas.[21] This led many Filipino brides find their way to South Korea and migrate over there.[21]

Below are the foreigner groups in South Korea that number more than 5,000.

| Nationalities of foreign nationals in South Korea (2016 Census) | |

|---|---|

| 1,016,607 | |

| 149,384 | |

| 140,222 | |

| 100,860 | |

| 56,980 | |

| 54,490 | |

| 51,297 | |

| 47,606 | |

| 45,832 | |

| 35,206 | |

| 34,108 | |

| 34,003 | |

| 27,650 | |

| 26,107 | |

| 22,455 | |

| 16,913 | |

| 16,728 | |

| 15,482 | |

| 13,870 | |

| 12,639 | |

| 11,895 | |

| 10,515 | |

| 9,484 | |

| 7,180 | |

| 6,709 | |

| 5,292 | |

| 5,005 | |

Languages

The Korean language is the native language spoken by the vast majority of the population. English is widely taught in both public and private schools as a foreign language. However, general fluency in English in the country is relatively low compared to other industrialized developed countries. There is a Chinese minority who speak Mandarin and Cantonese. Some elderly may still speak Japanese, which was official during the Japanese rule in Korea (1905–1945).[22][22]

In different areas of South Korea, different dialects are spoken. For example, the Gyeongsang dialect spoken around Busan and Daegu to the south sounds quite rough and aggressive compared to standard Korean.[22]

Religion

Koreans have historically, lived under the religious influences of shamanism, Buddhism, Daoism, or Confucianism.[23]

Korea is a country where the world's most major religions, Christianity, Buddhism, Confucianism and Islam, peacefully coexist.[24] According to 2005 statistics, 53% of Korean population has a religion and 2008 statistics show that over 510 religious organizations were in the South Korea population.[24]

- Nonreligious: 46.5%

- Buddhism: 22.8%

- Protestantism: 18.3%

- Catholicism: 10.9%

- Other: 1.4%

CIA World Factbook demographic statistics

The following demographic statistics are from the CIA World Factbook, unless otherwise indicated.[25]

| Year | Population | Growth rate | Age structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 50,924,172 | 0.53% |

|

| 2007 | 49,044,790 | 0.578% |

|

| 2006 | 48,846,823 | 0.58% |

|

Age structure

- 0–14 years: 13.21% (male 3,484,398/female 3,276,984)

- 15–24 years: 12.66% (male 3,415,998/female 3,065,144)

- 25–54 years: 45.52% (male 11,992,462/female 11,303,726)

- 55–64 years: 14.49% (male 3,660,888/female 3,756,947)

- 65 years and over: 14.12% (male 3,080,601/female 4,144,151) (2017 est.)

Literacy

- Definition: age 15 and over can read and write

- total population: 97.9%

- male: 99.2%

- female: 96.6% (2002)

Koreans living overseas

Large-scale emigration from Korea began around 1904 and continued until the end of World War II. During the Korea under Japanese rule period, many Koreans emigrated to Manchuria (present-day China's northeastern provinces of Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang), other parts of China, the Soviet Union, Hawaii, and the contiguous United States.

Most emigrated for economic reasons; employment opportunities were scarce, and many Korean farmers lost their land after the Japanese introduced a system of land registration and private land tenure, imposed higher land taxes, and promoted the growth of an absentee landlord class charging exorbitant rents. Koreans from the northern provinces of Korea went mainly to Manchuria, China, and Siberia. Many people from the southern provinces went to Japan. Koreans were conscripted into Japanese labor battalions or the Japanese army, especially during World War II. In the 1940–44 period, nearly 2 million Koreans lived in Japan, 1.4 million in Manchuria, 600,000 in Siberia, and 130,000 in China. An estimated 40,000 Koreans were scattered among other countries. At the end of World War II, approximately 2 million Koreans were repatriated from Japan and Manchuria.

More than 4 million ethnic Koreans lived outside the peninsula during the early 1980s. The largest group, about 1.7 million people, lived in China, the descendants of the Korean farmers who had left the country during the Japanese occupation. Most had assumed Chinese citizenship. The Soviet Union had about 430,000 ethnic Koreans.[26]

By contrast, many of Japan's approximately 700,000 Koreans had below-average standards of living. This situation occurred partly because of discrimination by the Japanese majority and partly because a large number of resident Koreans, loyal to the North Korean regime of Kim Il Sung, preferred to remain separate from and hostile to the Japanese mainstream. The pro–North Korea Chongryon (General Association of Korean Residents in Japan) initially was more successful than the pro–South Korea Mindan (Association for Korean Residents in Japan) in attracting adherents among residents in Japan. Since diplomatic relations were established between Seoul and Tokyo in 1965, however, the South Korean government has taken an active role in promoting the interests of their residents in Japan in negotiations with the Japanese government. It also has provided subsidies to Korean schools in Japan and other community activities.

By the end of 1988 there were over two million South Koreans residing overseas. North America was the destination of over 1.2 million. South Koreans also were residents of Australia (100,000), Central and South America (45,000), the Middle East (12,000), Western Europe (40,000), New Zealand (30,000), other Asian countries (27,000), and Africa (25,000). A limited number of South Korean government-sponsored migrants settled in Chile, Argentina, and other Latin American countries.

Because of South Korea's rapid economic expansion, an increasing number of its citizens reside abroad on a temporary basis as business executives, technical personnel, foreign students, and construction workers. A large number of formerly expatriate South Koreans have returned to South Korea primarily because of the country's much improved economic conditions and the difficulties they experienced in adjusting to living abroad.

See also

References

- ↑ "South Korea's population passes 50 million". June 22, 2012.

- ↑ These estimates are based on UN population division of 2017 version.

- ↑ "Population, total | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- 1 2 "South Korea Population (2018) - Worldometers". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ Andrea Matles Savada (1992). South Korea: A Country Study. p. 79. ISBN 9780788146190.

- ↑ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2007). "United Nations World Population Prospects: 2006 revision, Table A.15" (PDF). New York: UN. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ↑ Publication http://countrystudies.us/south-korea/33.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 "South Korea | Culture, History, and People - Settlement patterns". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ Thomas Klassen "South Korean: Ageing Tiger", Global Brief, January 12, 2010, accessed February 13, 2011.

- ↑ Neil Howe, Richard Jackson, Keisuke Nakashima. The Aging of Korea: Demographics and retirement policy in the land of the morning calm. Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2007, p. 7.

- 1 2 Jung Ha-won "Statistics highlight scale of the aging population", Korea JoongAng Daily, November 21, 2009, accessed February 14, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas Klassen "South Korean: Aging Tiger", Global Brief, January 12, 2010, accessed February 13, 2011.

- ↑ Spectre of aging population worries economists. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, Volume 88, Number 3, March 2010, p. 161-240.

- ↑ "South Korea - urbanization 2006-2016 | Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- 1 2 "World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision". Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Life expectancy". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ "World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations". Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Max Roser (2014), "Fertility Rate", Our World In Data, Gapminder Foundation

- ↑ "Press Releases - Population and Households". Statistics Korea. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ Yonhap News. "South Korea's foreign population passes the million mark for the first time in history". Hankyoreh.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Ethnic Minorities And Immigrants In South Korea". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- 1 2 3 "Languages in South Korea". Gap Year. 2015-04-08. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ "Historical and Modern Religions of Korea". Asia Society. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- 1 2 (KOCIS), Korean Culture and Information Service. "Religion : Korea.net : The official website of the Republic of Korea". www.korea.net. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- ↑ South Korea: A Country Study. DIANE Publishing Company, p. 86.

External links

- Korean Statistical Information System

- South Korea: Balancing Labor Demand with Strict Controls, Park Young-bum, Migration Information Source, December 2004.

- HelpAge International

- HelpAge Korea (in Korean)