Magars

|

Girls from Magar tribes in their traditional dresses | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,877,733[1] | |

| Languages | |

|

Magar language मगर भाषा | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Shamanism, Hinduism, Buddhist |

The Magars are one of the ethnolinguistic groups of Nepal representing 7.13% of the Nepal's total population as per the census of 2011. Their ancestral homeland extends from the Western and the Southern edges of the Dhaulagiri range of the Himalayas to the Mahabharat foothills in the South and Kali Gandaki river basin in the East.

The Magars ruled while establishing their own kingdoms in ancient Nepal similar time with khas kingdom baise (22) and (24) chaubise kingdom called the Bara Magaranth (12 Magar Kingdoms) located east of the Gandaki River and the Athara Magaranth (18 Magar Kingdoms) located west of the Gandaki River inhabited by the Kham Magars.

Origin

Mythical stories on the Origins of Magars: There are interesting mythical stories describing the origins of Magars. Three different versions relative to three different language groups are presented.[2]

The Magar of the Bahra Magaranth east of the Kali Gandaki River are said to have originated in the land of Seem. Two brothers, Seem Magar and Chintoo Magar, fought, and one remained in Seem, while the other left, ending up in Kangwachen in southern Sikkim. The Bhutia people lived at the northern end of this region. Over time, the Magars became very powerful and made the northern Bhutia their vassals. Sintoo Sati Sheng ruled in a very despotic manner, and the Bhutia conspired to assassinate him. Sheng's queen took revenge and poisoned 1,000 Bhutia people at a place now called Tong Song Fong, meaning "where a thousand were murdered". The Bhutia later drove the Magar out, forcing them to again migrate further south. As part of this migration, one group migrated to Simrongadh, one group moved towards the Okhaldhunga region, and another group seems to have returned to the east. No dates are given.

A second Magar federation called Athara Magarat was situated west of the Gandaki River, inhabited by western magars.

History

The first written history about Magar people dates as back as 1100 AD.[3] But it is widely accepted that they have resided around Palpa from time immemorial. They are also thought to be the earliest settlers from the north. This part of the country was formerly divided into twelve districts, each under its own ruler, being known as the Barah, or twelve Magarant[4] or twelve Thams, the members of each supposedly being of common extraction in the male line. Some records show these twelve areas as being Arghakhanchi, Gulmi, Isma, Musikot, Khanchi, Ghiring, Rising, Bhirkot, Payung, Garhung, Dhor and Satung.[5] However, it is probable that some of the latter places should have been excluded in favour of Palpa, Galkot, Dhurkot, Char Hajar, Parbat, and even Piuthan and Salyan.[6]

The Magars of middle and western region also played a role in Nepal's formative history. Their kingdom was one of the strongest of west Nepal in and around Palpa District during the time of the 22 and 24 rajya principalities (17th and early 18th centuries).[7] The 18th-century king, Prithvi Narayan Shah, the founder of the modern Kingdom of Nepal was announced and loved to call himself the King of Magarat.

Many prominent historians of Nepal have claimed that Aramudi, an eighth-century ruler of the Kali Gandaki region, was a Magar King.[8][9][10][11] "Aramudi" derives from the word for 'river' in the Magar language.[12] 'Ari'-'Source of Water' + 'Modi'-'River'='Arimodi' or 'Aramudi', thus the literal meaning of Aramudi is source of river. But due to the lack of historical evidence there are some conflicting ideas among the historians.

Subdivisions

The Magars are structured with septs (clans), followed by sub-septs (sub-clans).

Broadly speaking, Magars are divided into two main groups: Baraha Magaratis and Athara Magaratis. Before the unification of Nepal in the 18th century by the King Prithvi Narayan Shah, the Magarat land was divided into two Magarat states. West of Kali Gandaki was called eighteen Magarat and East of Kali Gandaki was called twelve Magarat. They are mainly Ale, Budha, Pun, Rana and Thapa clans. Within these seven clans, more than 1100 sub-clans can be found. These Magar clans intermarry with one another and are equal in social standing.[6]

Linguistically, the Magars are divided into three groups. Baraha Magaratis speak Dhut dialect, whereas Athara Magaratis speak Pang and Kaike dialects.

MagarDhut-speakers: Rana, Gaha, Ale, Thapa, Gurmachan, Singjali, Laya, Rakhal, Ashlami, Gahaga, Darlami, Masarangi, Khadka, Gharti, Naamjyali, Bucha, Saru, Khamcha, Pulami, mangrati/magarati and all magar clans and sub clans residing in twelve Magarats.

MagarPang-speakers: Ale, Budha, Gurmachan, Gharti, Pun, Rana, Laya, Gaha, Roka, /magarati,Thapa,Jhankri,Shreesh, Burathoki,Garbuja,Purja,Ramjali,jugjali and all magar clans and sub clans residing in eighteen Magarat.

KaikeMagar-speakers: similar with pawei khas language. Tarali Magar of Dolpa/Budha, Gharti, Roka magar, Kayat, rana , thapa, Jhankri all Magar clans residing in Dolpa and Karnali districts .

Language

Of the 2,064,000 Magar people in Nepal, nearly 788,530 speak a Magar language as their mother tongue. Most of the others speak Nepali as their mother tongue. The western inhabitants of Nepal did not speak the language in the past. But recently, almost everyone has started learning the language. The western magars of Rapti Zone speak Magar Pang kura. In Dolpa District, the Magar speak Magar Kaike language. The Magar languages are rooted in the Bodic branch of the Tibetan family. Magar Dhut kura speakers are all Magar clans residing in twelve Magarats. Similarly Magar Pang kura speakers are all magar clans from eighteen Magarats. Magar Kaike language speakers are all magar clans in Karnali zone. The 1971 census put the total population of those who spoke the Magar language at 288,383, i.e. 2.49 percent of the total population of Nepal, of which more than half lived in the Western hills of Nepal.[13]

Magar Words in Use

Many Magar words are used even today, especially as location names. Magar toponyms in Nepali include: tilaurakot (place selling sesame seed), kanchanjunga (clear peak), and * Tansen (straight wood)[14] Some scholars opine that the amount of Magar words in Nepali indicates that Magarat (historic Magar lands) were larger than generally believed, extending from Dhading to Doti.[15] They note that the place suffix -Kot indicates a place from which Magar kings formerly ruled.

Religion

Magar follow hardcore hinduism the social process of Sanskritization has drawn some southern Magar population to develop a syncretic form of hindism that combines animist and hindu rituals. The original religions or beliefs of Magar people are Shamanism, Animism, Ancestor worship, hinduism and the northern nepals Magar follow shamanism(Bon).

Many Magar Priests got mixed into khas Society and became one of them. Now days rana. Budha. Budathoki. Gharti. Thapa. khadka. Lamichaney. Budhathapa. Magars are mixture of khas people

Animists and shamanism form part of the local belief system; their dhami (the faith healer or a kind of shaman) is called Dangar and their jhankri (another kind of faith healer or shaman) is called was the traditional spiritual and social leader of the Magars.[16] Magars have an informal cultural institution, called Bhujel, who performs religious activities, organizes social and agriculture-related festivities, brings about reforms in traditions and customs, strengthens social and production system, manages resources, settles cases and disputes and systematizes activities for recreation and social solidarity.[17]

Dress and ornaments

The Magar of the low hills wear the ordinary kachhad or wrap-on-loincloth, a bhoto or a shirt of vest, and the usual Nepali topi. The women wear the pariya or lunghi, chaubandhi cholo or a closed blouse and the heavy patuka or waistband, and the mujetro or shawl-like garment on the head. Men living in the Tarakot area even wear the Tibetan chhuba. The ornaments are the madwari on the ears, bulaki on the nose and the phuli on the left nostril, the silver coin necklace"[haari]" and the pote (yellow and Green beads) with the tilhari gold cylinder, [jantar], [dhungri], [naugedi], [phul] and kuntha. Magar males do not wear many ornaments, but some are seen to have silver earrings, hanging from their earlobes, called "gokkul". The magar girls wear the amulet or locket necklace, and women of the lower hills and the high-altitude ones wear these made of silver with muga stones embedded in them and kantha. The bangles of silver and glass are also worn on their hands along with the sirbandhi, sirphuli and chandra on their heads. These are large pieces of gold beaten in elongated and circular shapes. Magar women used to originally wear blue colored patuka or waistband but recently, they started to wear yellow patuka to distinguish themselves from Gurung women. But still, in many parts of the country some magar women wear blue colored patuka unknowingly.

Dance and songs

There are many forms of magar dances, those which are performed by magars all over the world commonly as well as those which are performed regionally by the magars of a particular region. The most commonly known magar dances are maruni, kauda, ghatu, sorathi and salaijo dances.The regional magar dances include: Bhume nach(Land worshipping dance) performed by the magars of Rolpa and Rukum, Thali nach(Plate dance) performed by the magars of Baglung, mayur nach(peacock dance) performed by the magars of Rolpa and Rukum, etc. Recently, these regional dances are being performed by the magars of other regions as well. Magar songs include: salaijo, kauda, rodhi, sorathi, etc.

Occupations

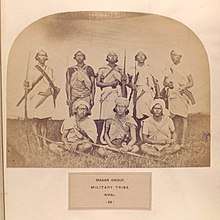

Agriculture and the military are the primary sources of income. Magars constitute the largest number of Gurkha soldiers outside Nepal.[18][19] Sarbajit Rana Magar became the head of government during the regency of Queen Rajendra Laxmi.[20] Biraj Thapa Magar winner of limbuwan, and Sarbajit Rana Magar headed the Nepal army. Biraj Thapa Magar was the very first army chief in Nepal Army's history.[21] Magars are famous as gallant warriors wherever they served in the past. The Magars are well represented in Nepal's military, as well as in the Singapore Police Force, the British and Indian Gurkha regiments. They are also employed as professionals in the fields of medicine, education, government service, law, journalism, development, aviation and in business in Nepal and other countries.

Dor Bahadur Bista's observation of Magar's occupation during the 1960s was:

Some of the northernmost Magars have become quite prosperous by engaging in long-range trading that takes them from near the northern border to the Terai, and even beyond to Darjeeling and Calcutta. Were it not for their role in the Gurkha regiments of the Indian and British armies, their self-sufficiency might be endangered.[22]

Toni Hagen, who did his field research in Nepal during the 1950s, observed:

Magars possess considerable skill as craftsmen: they are the bridge builders and blacksmiths among the Nepalese, and the primitive mining is largely in their hands. On the lower courses of the Bheri & Karnali rivers, a great number of Magars annually migrate to the Terai & there manufacture bamboo panniers, baskets, and mats for sale in the bazaars along the borders. In their most northerly settlement, on the other hand, the important trading centre of Tarakot on the Barbung river, they have largely adopted their way of life, their clothes, and their religion to that of the Tibetans; like the latter, they also live by the salt trade. As regard race, the Magars have almond-shaped eyes or even open eyes, whereas Mongoloid eyes are very rare.[23]

Military service

A number of Magars have distinguished themselves in military service under the British military. Dipprasad Pun was the first Nepali winner of the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross in Afghanistan in 2010. In the two world wars, total 5 Victoria Cross (out of 13 VCs awarded to Gurkhas) were awarded to the Magars:[24]

- First World War:

- Rifleman Kulbir Thapa was the very first Gurkha to win VC in recognition of his valor and bravery. He was from Gulmi, Bharse. He served in 2/3 Gurkha Regiment (GR). He received VC in France in 1915.

- Rifleman Karanbahadur Rana, Gulmi was from 2/3 GR. He received VC in Egypt in 1918.

- Second World War:

- Subedar Lalbahadur Thapa, Nepal Tara[25] was from 2nd GR. He received VC in Tunisia in 1943.

- Honorable Lieutenant Tul Bahadur Pun was from 6th GR. He received VC in Burma in 1944.

- Subedar Netrabahadur Thapa was from 5th GR. He received VC in Burma in 1944.

Notable Magars

- Kaji Biraj Thapa Magar, the very first Chief of Nepalese Army, 18th century.

- General Abhiman Singh Rana Magar, Nepalese Army Chief, 19th century.

- Narayan Singh Pun, a former minister in Nepal, pilot and lieutenant colonel in the Royal Nepal Army. Also founding president of Nepal Samata Party.

- Master Mitrasen Thapa, famous Nepali folk singer, social worker, resident of Bhagsu/Dharmasala, (India).

- Gore Bahadur Khapangi, former minister and founding leader of Prajatantrik Janamukti Party.

- Giri Prasad Burathoki, only Bada Hakim from Magars, Defense Minister, Honorary Major General of Nepalese Army.

- Onsari Gharti Magar, the first female speaker of Parliament of Nepal.

- Balaram Gharti Magar, held different ministries for 11 times including Defense Minister of Nepal Government.

- Lakhan Thapa Magar, first martyr of Nepal.

- Jaybahadur Hitan Magar, 1st Central Executive Committee (Damauli, 2039 B.S.) Secretary of Nepal Magar Association.

- Rom Bahadur Thapa, First Inspector General of Nepal Police from Magar ethnic group.

- Khadga Jeet Baral Magar, Ex IGP, Chief of Nepal Police.

- Teriya Magar, Dancer.

- Barsaman Pun, first finance minister of Nepal from Magar community. He is from Rolpa district.

- Nanda Bahadur Pun, first vice president of federal republic Nepal.

- Kuber Singh Rana, ex IGP Chief of Nepal Police from Palpa.

- Mahabir Pun, Magsaysay Award winner for extending wireless technologies in rural parts of Nepal.

- Bimal Gharti Magar, Football player

Politics

Under the leadership of minister Giri Prasad Burathoki, a first ever Magar Convention was held in Bharse of Gulmi District, one of the 12 Magarats in 1957. The objective of the conference was to sensitize the Magars to come forward in the national spectrum.[26]

Later Magar political and social organisations included Nepal Langhali Pariwar (1972), Nepal Langhali Pariwar Sang, and Langhali Pariwar Sangh.

Notes

- ↑ cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/National%20Report/National%20Report.pdf

- ↑ Tribal Ethnography of Nepal, Volume II, by Dr. Rajesh Gautam and Asoke K. Thapa Magar.

- ↑ Eden Vansittart. 1993 (reprint). Sohab Rana Magar was also a ruler in Dullu Dailekh, western Nepal in AD 1100 (the earliest copper plate inscription from Nepal, 1977); a copper plate. The Gurkhas. New Delhi:Anmol Publications. p.21.

- ↑ Northey, W. Brook & C. J. Morris. 1927. The Gurkhas Their Manners, Customs and Country. Delhi : Cosmo Publications. (122-125)

- ↑ Brian Hodgson and Captain T Smith also give this information. Eden Vansittart. 1993 reprint. The Gurkhas. p.84.

- 1 2 Ministry of Defence. 1965. Nepal and the Gurkhas. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.p. 27.

- ↑ Dor Bahadur Bista. 1972. People of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar. p. 62.

- ↑ Tek Bahadur Shrestha. 2003. Parvat Rajyako Aitihasik Ruprekha. Kirtipur: T.U.

- ↑ Dr Swami Prapannacharya. (1994-95) Ancient Kirant History. Varanasi: Kirateshwar Prakashan. p. 518.

- ↑ Hark Gurung, Iman Singh Chemjong, B.K. Rana, Prof. Raja Ram Subedi, Prof. Jagadish Chandra Regmi etc. support the conclusion of Aramudi being the king of Kali Gandaki Region.

- ↑ Mahesh Chaudhary. 2007. "Nepalko Terai tatha Yeska Bhumiputraharu". p. 9

- ↑ Tek Bahadur Shrestha. Op. cit.

- ↑ Rishikesh Shaha. 1975. An Introduction of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar. p. 38.

- ↑ Balaram Gharti Magar. 1999. Roots. Tara Nath Sharma (Tr.). Lalitpur: Balaram Gharti Magar.

- ↑ Balaram Gharti Magar, 1999. Ibid.

- ↑ , 1996:66

- ↑ . 1996. "Bheja as a Cultural Strategic Cultural Convention. Community Resource Management in the Barha Maagarat." Occasional Papers in Sociology and Anthropology, Volume 5, Tribhuvan University.

- ↑ Dor Bahadur Bista. 1972. People of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar. p.664.

- ↑ Eden Vansittart. 1993 (Reprint). The Gurkhas. New Delhi: Anmol Publications. p.67.

- ↑ Rishikesh Shaha. 1975. p.32.

- ↑ Army Chiefs' Historical Record. Army Museum. Chhauni, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- ↑ Dor Bahadur Bista. 1972. p.64.

- ↑ Tony Hagen. 1970. Nepal the Kingdom in the Himalayas. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. p.84.

- ↑ Y.M. Bammi. 2009. Gorkhas of the Indian Army. New Delhi: Life Span Publishers & Distributors. p.93.

- ↑ Pradeep Thapa Magar. 2000. Veer Haruka pani Veer Mahaveer. p.9.

- ↑ B. K. Rana - Sanchhipta Magar Itihas 2003 - p. 82

References

- Acharya, Baburam, Nepalako Samkshipta Itihasa (A short history of Nepal), edited by Devi Prasad Bhandari, Purnima No. 48, Chaitra 2037 (March–April 1981), Chapter VII: Pachhillo Licchavi Rajya, (I. Sam. 642-880 Am.)

- Aryal, Jibnarayan. (2058BS). Dr Harsha Bahadur Buda Magar: Bigat ra Bartaman. Lalitpur: Dr Harsha Bahadur Budha Magar.

- Bajracharya, Dhanabajra. (2064 BS). Gopalraj Vanshawali Aitihasik Vivechana. Kirtipur: T.U.

- Bammi, Y.M. (2009). Gurkhas of the Indian Army. New Delhi: Life Span Publishers & Distributors.

- Bamzai, P.N.K. (1994). Culture and Political History of Kashmir. Vol 1. Ancient Kashmir. New Delhi: MD Publications Pvt Ltd.

- Bista, Dor Bahadur. (1972). People of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

- Budha Magar, Harsha Bahadur. (1992)Kirat Vansha ra Magar haru. Kathmandu: Unnati Bohora.

- Cross, J.P. (1986). In Gurkhas Company. London: Arms & Armour Press Ltd.

- Gharti Magar, Balaram. (1999). Roots. Taranath Sharma (Tr.). Lalitpur: Balaram Gharti Magar.

- Hagen, Tony. (1970). Nepal the Kingdom in the Himalayas. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co.

- Ministry of Defence. (1965). Nepal and the Gurkhas. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Nepal, Gyanmani. (2040BS). Nepal Nirukta. Kathmandu: Nepal Rajakiya Pragyapratisthan.

- Northey, W. Brook & C. J. Morris. (1927). The Gurkhas Their Manners, Customs and Country. Delhi : Cosmo Publications.

- Palsokar, R.D. (1991). History of the 5th Gorkha Rifles (Frontier Force), Vol III. 1858 to 1991. Shillong: The Commandant, 58 Gorkha Training Centre.

- Rana, B. K. (2003). Sanchhipta Magar Itihas (A Concise Hiostroy of Magars)

- Shaha, Rishikesh. (1975). An Introduction of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

- Stein, M.A. (2007). Kalhana's Rajatarangini: A Chronicles of Kings of Kashmir. Vol I, II, & III (Reprint). Srinagar: Gulshan Books.

- Sufi, G.M.D. (1974). Kashir a History of Kashmir. Vol 1. New Delhi: Light & Life Publishers.

- Thapa Magar, Pradeep. (2000). Bir Haruka pani Bir Mahavir. Kathmandu: Bhaktabir Thapa Magar.

- Vansittart, Eden. (1993)(reprint). The Gurkhas. New Delhi: Anmol Publications.

- Pramod Thapa (Chief engineer at Dell international Services)

- An account Kingdom of Nepal Frances Hamilton, Rishikesh Shah,

External links

| Magars test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |