Ethnicities in Iran

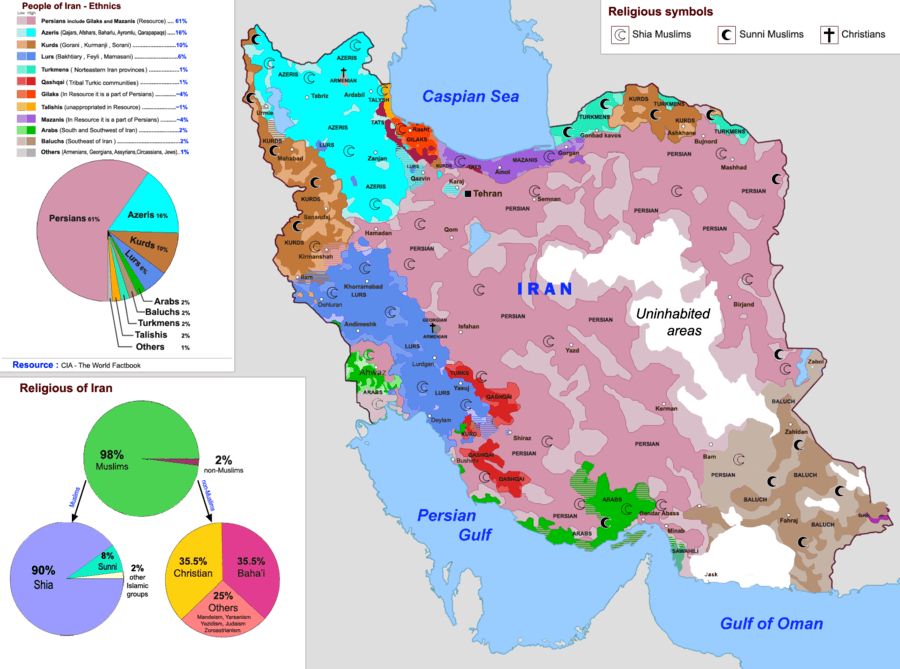

A majority of the population of Iran (approximately 67–80%) consists of Iranic peoples.[2][3][4][5] The largest groups in this category include Persians (who form the majority of the Iranian population) and Kurds, with smaller communities including Gilakis, Mazandaranis, Lurs, Tats, Talysh, and Baloch.

Turkic groups constitute a substantial minority of about 15–24%, the largest group being the Azerbaijani, who are the second largest ethnicity in Iran as well as the largest minority group.[6] Other Turkic groups include the Turkmen and Qashqai peoples.

Arabs account for about 2–3% of the Iranian population. The remainder, amounting to about 1% of Iranian population, consists of a variety of minor groups, mainly comprising Assyrians, Armenians, Georgians, Circassians,[7] and Mandaeans.[8]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Iran had a total population of just below 10 million, with an approximate ethnic composition of: 6 million Persians (60%), 2.5 million Azeris (25%), 0.2 million Mazandaranis and Gilakis each (2% each).[9]

Iranian-speaking peoples

Persians

Iran used to be called Persia until 1935, by that definition all Iranians were considered Persian regardless of their ethnicity. The term "Persians" refers to an ethnic group who speak the Western dialect of Persian and live in the modern country of Iran as well as the descendants of the people who emigrated from the territory of modern-day Iran to other countries.

Ethnic Persians inhabit traditionally the Tehran province, Isfahan province, Fars province, Alborz province, Razavi Khorasan, South Khorasan, Yazd province, Kerman province, Bushehr province, Hormozgan province, Markazi province (Arak), Qom province, Semnan province, Qazvin province, the majority of Hamadan province including the city of Hamadan, majority of the North Khorasan, majority of Khuzestan province, northern half of Sistan and Baluchistan (Zabol), southern and western half of Golestan province including the provincial capital of Gorgan. The majority of the Iranian immigrants in the West and other parts of the world also hail from Persian speaking cities especially from Tehran.

According to the CIA World Factbook, Persians in Iran constitute up to 61% of the country's population.[10][11] Another source, Library of Congress [12] states Iran's Persians compose 65% of the country's population.[2] However, other sources mention that Persians only comprise 50.5%,[13] or 55.3%.[14] All these numbers include the Mazandaranis and Gilakis as Persian people, though the CIA World Factbook makes a distinction between the Persian language and the Mazandarani and Gilaki language, respectively.[10][11]

Kurds

Iranian Kurds make up the majority of the population of Kordestan province, and, together with the Azeris, they are one of the two main ethnic groups in West Azerbaijan province. In West Azerbaijan province, Kurds are concentrated in parts of the southern and western parts of the province. The Feyli tribe of Kurds also make up a significant proportion of the populations of Kermanshah and Ilam provinces, although Kermanshahi and Ilamian Kurds are Shia Muslims, in contrast to the mainstream Kurds, who are adherents of Sunni Islam. Kurmanji-speaking Kurds also form a plurality in North Khorasan province.

Mazandaranis

The Mazanderani people [15] or Tabari people are an Iranian people whose homeland is the North of Iran (Tabaristan). Like the closely related Gilaks, the Mazanderanis are a Caspian people who inhabit the south coast of the Caspian Sea, part of the historical region that used to be called Tabaristan and are currently one of the main ethnic groups residing in the northern parts of Iran. They speak the Mazandarani language, a language native to around 4 million people, but all of them can speak Persian. The Alborz mountains mark the southern boundary of Mazanderani settlement.[16] The Mazanderani peoples number differs between three million and four million (2006 estimate) and many of them are farmers and fishermen.[17]

Gilaks

The Gilaki people or Gilaks are an Iranian people native to the northern Iran province of Gilan and are one of the main ethnic groups residing in the northern part of Iran. Gilaks, along with the closely related Mazandarani people, comprise part of the Caspian people, who inhabit the southern and southwestern coastal regions of the Caspian Sea. They speak the Gilaki language and their population is estimated to be between 3 [18] to 4 [19] million (4% of the population). Gilaki people live both alongside the Alborz mountains, and in the surrounding plains. Consequentially, those living along the northern side of the Alborz mountains tend to raise livestock, while those living in the plains farm. Gilaks play an important role in provincial and national economy, supplying a large portion of the region's agricultural staples, such as rice, grains,[20] tobacco [21] and tea.[22] Other major industries include fishing and caviar exports, and the production of silk.[23]

Lurs

Lur people speak the Luri language and inhabit parts of west – south western Iran.[24] Most Lur are Shi’a. They are the fourth largest ethnic group in Iran after the Persians, Azeri, and Kurds.[13][25] They occupy Lorestan, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Khuzestan, Isfahan, Fars, Bushehr and Kuh-Gilu-Boir Ahmed provinces.[24] The authority of tribal elders remains a strong influence among the nomadic population. It is not as dominant among the settled urban population. As is true in Bakhtiari and Kurdish societies, Lur women have much greater freedom than women in other groups within the region.[26] The Luri language is Indo-European. The Lur people may be related to the Kurds from whom they "apparently began to be distinguished from... 1,000 years ago." The Sharafnama of Sharaf Khan Bidlisi "mentioned two Lur dynasties among the five Kurdish dynasties that had in the past enjoyed royalty or the highest form of sovereignty or independence."[27] In the Mu'jam Al-Buldan of Yaqut al-Hamawi mention is made of the Lurs as a Kurdish tribe living in the mountains between Khuzestan and Isfahan. The term Kurd according to Richard Frye was used for all Iranian nomads (including the population of Luristan as well as tribes in Kuhistan and Baluchis in Kerman) for all nomads, whether they were linguistically connected to the Kurds or not.[28]

Talysh

The Talysh of Iran are about 430,000 and live mostly in the province of Gilan in north of Iran. They are indigenous to a region shared between Azerbaijan and Iran which spans the South Caucasus and the southwestern shore of the Caspian Sea. Another significant amount of Talysh live therefore also in the Republic of Azerbaijan.[29]

Tats

The Tats of Iran are centralised near the Alborz Mountains, especially in the south of Qazvin province. They speak the Tati language, consisting of a group of northwestern Iranian dialects closely related to the Talysh language. Persian and Azeri are also spoken. Tats of Iran are mainly Shia Muslims and about 300,000 population.[30][31][32][33][34][35][36]

Baloch

The Baloch people of Iran live in southern and central parts of Sistan and Baluchestan province, one of the most remote and isolated areas of Iran, especially from the majority of the people. The northern part of the province is called Sistan and 63% of the population are ethnic Baloch while the rest are Persian Sistani. The Baloch are Sunni Muslims, in contrast to the Sistani Persians who are adherents of Shia Islam. The capital of Sistan and Baluchestan is Zahedan and is inhabited by Baloch people, the next largest city of the province is Zabol in Sistan and is inhabited predominantly by Persians. The town of Jask in neighbouring Hormozgan Province is also inhabited by Baloch people. They form one of the smallest ethnicities in Iran.

Turkic

The largest Turkic group in Iran are the Iranian Azerbaijanis, forming the second largest ethnicity in the nation after the majority Persian population.[6]

Smaller Turkic groups account for about 2% of Iranian population between them,[25][37] about half of this number is accounted for by the Iranian Turkmen, the other half comprises various tribal confederacies such as the Qashqai or the Khorasani Turks.

Azerbaijanis

Iranian Azerbaijanis (also known as Iranian Turks) are a Turkic-speaking people of mixed Caucasian, Iranian and Turkic origin,[38] who live mainly in Iranian Azerbaijan. Estimated numbers or percentages vary significantly and many estimates cited appear to be politically motivated[39]. They are often considered the second largest ethnic group in Iran and the largest ethnic minority. The main estimations are stated below :

- 15%e[40]

- 15.5%f[41]

- 16%a[42][43]g[4][5][44][45]

- 17%b[46]

- 21.6c[47]

- 24-25 percentd[48][49][50]

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1765. ISBN 978-0-313-32384-3 "Approximately (2002e) 18,500,000 Southern Azeris in Iran, concentrated in the northwestern provinces of East and West Azerbaijan. It is difficult to determine the exact number of Southern Azeris in Iran, as official statistics are not published detailing Iran's ethnic structure. Estimates of the Southern Azeri population range from as low as 12 million up to 40% of the population of Iran – that is, nearly 27 million..."[50][51][52]

In the Azerbaijan region, the population consists mainly of Azerbaijanis.[53] Azeris form the largest ethnic group in Iranian Azerbaijan, while Kurds are the second largest group and a majority in many cities of West Azerbaijan Province.[54] Iranian Azerbaijan is one of the richest and most densely populated regions of Iran. Many of these various linguistic, religious, and tribal minority groups, and Azeris themselves have settled widely outside the region.[55] The majority of Azeris are followers of Shi'a Islam. Iranian Azerbaijanis mainly reside in the northwest provinces, including the Iranian Azerbaijan provinces (East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, and Zanjan), as well as regions of the North[56] to Hamadan County[57] and Shara District[57] in the East Hamadan Province, and some regions of Qazvin Province.[58][59] Some Azerbaijani minorities also live in Markazi,[60] Kordestan,[61] Gilan[62][63] and Kermanshah provinces.h[64] Azerbaijanis also make up significant minorities in various parts of central Iran, especially Tehran,[65] where they constitute around 25%[66] to one-third of the population.[58][59][67]

Turkmen

Iranian Turkmen are primarily concentrated in the provinces of Golestān and North Khorasan. The largest Turkmen city in Iran is Gonbad-e Kavoos, followed by Bandar Torkaman. Iranian Turkmen are mostly Sunni Muslims.

Turkic tribal groups

The Qashqai people mainly live in the provinces of Fars, Khuzestan and southern Isfahan, especially around the city of Shiraz in Fars. They speak the Qashqai language which is a member of the Turkic family of languages. The Qashqai were originally nomadic pastoralists and some remain so today. The traditional nomadic Qashqai travelled with their flocks each year from the summer highland pastures north of Shiraz roughly 480 km or 300 mi south to the winter pastures on lower (and warmer) lands near the Persian Gulf, to the southwest of Shiraz. The majority, however, have now become partially or wholly sedentary. The trend towards settlement has been increasing markedly since the 1960s.[68]

The Khorasani Turks are Turkic-speaking people inhabiting parts of north-eastern Iran, and in the neighbouring regions of Turkmenistan up to beyond the Amu Darya River. They speak the Khorasani Turkic and live in North Khorasan, Razavi Khorasan, and Golestan provinces alongside Turkmens.

Semitic

Arabs

2% of Iran's citizens are Arabs.[11] A 1998 report by UNCHR reported 1 million of them live in border cities of Khuzestan Province, they are believed to constitute 20% to 25% of the population in the province, most of whom being Shi'a. In Khuzestan, Arabs are a minority in the province. They are the dominant ethnic group in Shadegan, Hoveyzeh and Susangerd, a significant group in the rural areas of Abadan (The city of Abadan is inhabited by Iranians who speak the Abadani dialect of Persian as well as Arabs), and together with Persians, Arabs are one of the two main ethnic groups in Ahvaz. Most other cities in Khuzestan province are either inhabited by the Lur, Bakhtiari or Persian ethnic groups. The historically large and oil-rich cities of Mahshahr, Behbahan, Masjed Soleyman, Izeh, Dezful, Shushtar, Andimeshk, Shush, Ramhormoz, Baghemalak, Gotvand, Lali, Omidieh, Aghajari, Hendijan, Ramshir, Haftkel, Bavi are inhabited by people who speak either Luri, Bakhtiari and Persian languages.[69] There are smaller communities in Qom where there are a significant number of Arabs being of Lebanese descent, as well as Razavi Khorasan and Fars provinces. Iranian Arab communities are also found in Bahrain, Iraq, Lebanon, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

Assyrians

The Assyrian people of Iran are a Semitic people who speak modern Assyrian, a neo-Aramaic language descended from Classical Syriac, and are Eastern Rite Christians belonging mostly to the Assyrian Church of the East and, to a lesser extent, to the Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church and Ancient Church of the East.[70] They claim descent from the ancient peoples of Mesopotamis. They share a common identity, rooted in shared linguistic and religious traditions, with Assyrians in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East such as Syria and Turkey, as well as with the Assyrian diaspora.[70]

The Assyrian community in Iran numbered approximately 200,000 prior to the Islamic Revolution of 1979. However, after the revolution many Assyrians left the country, primarily for the United States, and the 1996 census counted only 32,000 Assyrians.[71] Current estimates of the Assyrian population in Iran range from 32,000 (as of 2005)[72] to 50,000 (as of 2007).[73] The Iranian capital, Tehran, is home to the majority of Iranian Assyrians; however, approximately 15,000 Assyrians reside in northern Iran, in Urmia and various Assyrian villages in the surrounding area.[70]

Jews

Judaism is one of the oldest religions practiced in Iran and dates back to late biblical times. The biblical books of Isaiah, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles, and Esther contain references to the life and experiences of Jews in Iran.

By various estimates, 10,800 Jews[74] remain in Iran, mostly in Tehran, Isfahan, and Shiraz. BBC reported Yazd is home to ten Jewish families, six of them related by marriage, however some estimate the number is much higher. Historically, Jews maintained a presence in many more Iranian cities. Iran contains the largest Jewish population of any Muslim country except Turkey.[75]

A number of groups of Jews of Iran have split off since ancient times. They are now recognized as separate communities, such as the Bukharan Jews and Mountain Jews. In addition, there are several thousand in Iran who are, or who are the direct descendants of, Jews who have converted to Islam and the Bahá'í Faith.[76]

Mandaeans

Iranian Mandaeans live mainly in the Khuzestan Province in southern Iran.[77] Mandeans are a Mandaic speaking Semitic people who follow their own distinctive Gnostic religion Mandaeism, venerating John the Baptist as the true Messiah. Like the Assyrians of Iran, their origins lie in ancient Mesopotamia. They number some 10,000 people in Iran,[78] though Alarabiya has put their number as high as 60,000 in 2011.[79]

Caucasus-derived groups

Armenians

The current Iranian-Armenian population is somewhere around 500,000.[80] They mostly live in Tehran and Jolfa district. After the Iranian Revolution, many Armenians immigrated to Armenian diasporic communities in North America and western Europe. Today the Armenians are Iran's largest Christian religious minority, followed by Assyrians.

Georgians

Iranian Georgians are Twelver Shia Muslims, whereas the vast majority of Georgians elsewhere in the world are Christian.

The Georgian language is the only Caucasian language fully functioning in Iran and it's spoken only by those that live in Fereydan and Fereydunshahr, and in smaller pockets all over Iran. Almost all other communities of Iranian Georgians in Iran have already lost their language, but retain a clear Georgian identity.

Once a very large minority in Iran mainly due to mass deportations by the various early modern age and modern age Iranian empires (Safavids, Afsharids, and Qajars), of their Georgian subjects, nowadays, due to intermarrying and assimilating the number of Georgians in Iran is estimated to be over 100,000. However, the amount of Iranians with partial or assimilated Georgian ancestry is estimated to exceed millions.

The Georgian language is still used by many of the Georgians in Iran. The centre of Georgians in Iran is Fereydunshahr, a small city 150 km to the west of Isfahan. The western part of Isfahan province is historically called Fereydan. In this area there are 10 Georgian towns and villages around Fereydunshahr. In this region the old Georgian identity is retained the best compared to other places in Iran. In many major Iranian cities, such as Tehran, Isfahan, Karaj and Shiraz, and Rasht live Georgians too.

In many other places such as Najafabad, Rahmatabad, Yazdanshahr and Amir Abad (near Isfahan) there are also Georgian pockets and villages. In Mazandaran Province in northern Iran, there are ethnic Georgians too. They live in the town of Behshahr, and also in Behshahr county, in Farah Abad, and many other places, which are usually called "Gorji Mahalle" (Georgian Neighbourhood). Most of these Georgians no longer speak the Georgian language, but retain aspects of Georgian culture and a Georgian identity. Some argue that Iranian Georgians retain remnants of Christian traditions, but there is no evidence for this.

Circassians

Like with the Georgians, once a very large minority in Iran all the way from the Safavid to the Qajar era, the vast majority of the Circassians have been assimilated into the population nowadays. However, significant numbers remain present,[81] and they are the second-largest Caucasian ethnic group in the nation after the Georgians.[81]

From Sir John Chardin's "Travels in Persia, 1673–1677":

There is scarce a Gentleman in Persia, whose Mother is not a Georgian, or a Circassian Woman; to begin with the King, who commonly is a Georgian, or a Circassian by the Mother's side.

Circassians alongside the Georgians were deported en masse by the Shah's to fulfil roles in the civil administration, the military, and the royal Harem, but also as craftsmen, farmers, amongst other professions.[82][83] Circassian women were both in Ottoman Turkey and Persia desired for their beauty, while the men were known as fearsome warriors. Notable Iranians of Circassian descent of the past include Teresia Sampsonia, Shah Abbas II, Shah Suleiman I, Pari Khan Khanum (daughter of Shah Tahmasp, involved in many court intrigues), Shamkhal Sultan, Jamshid Beg (the assassinator of Shah Ismail II), and Anna Khanum. Traces of Circassian settlements have lasted into the 20th century,[83] and small pockets still exist scattered over the country, even after centuries of absorbing and assimilating,[7][84] such as in Fars,[85] Rasht, Aspas, Gilan, Mazandaran, and the capital Tehran (due to contemporary internal migration). Their total number nowadays is unknown due to heavy assimilation and lack of censuses based on ethnicity, but are known to be significant.[81][84][86][87] Due to the same assimilation however, no sizeable number speaks the Circassian language anymore.[84]

Recent immigration

Most of the large Circassian migrational waves towards mainland Iran stem from the Safavid and Qajar era, however a certain amount also stem from the relatively recent arrivals that migrated as the Circassians were displaced from the Caucasus in the 19th century. A Black African population exists due to historical slavery. A substantial number of Russians arrived in the early 20th century as refugees from the Russian revolution, but their number has dwindled following the Iran crisis of 1946 and the Iranian Revolution. In the 20th to 21st centuries, there has been limited immigration to Iran from Turkey, Iraqis (especially huge numbers during the 1970s known as Moaveds), Afghanistan (mostly arriving as refugees in 1978), Lebanese (especially in Qom, though a Lebanese community has been present in the nation for centuries), Indians (mostly arriving temporarily during the 1950s to 1970s, typically working as doctors, engineers, and teachers), Koreans (mostly in the 1970s as labour migrants), China (mostly since the 2000s working in engineering or business projects), and Pakistan, partly due to labour migrants and partly to Balochi ties across the Iranian-Pakistani border. About 200,000 Iraqis arrived as refugees in 2003, mostly living in refugee camps near the border; an unknown number of these has since returned to Iraq.

Over the same period, there has also been substantial emigration from Iran, especially since the Iranian revolution (see Iranian diaspora, Human capital flight from Iran, Jewish exodus from Iran), especially to the United States, Canada, Germany, Israel, and Sweden.

See also

References

- ↑ CIA World Factbook: Iran

- 1 2 "Iran" in Encyclopedia of Islam, Leiden. C.E. Bosworth (editor): Persians (65 percent), Azeri Turks (16 percent), Kurds (7 percent), Lurs (6 percent), Arabs (2 percent), Baluchis (2 percent), Turkmens (1 percent), Turkish tribal groups such as the Qashqai (1 percent), and non-Persian, non-Turkic groups such as Armenians, Assyrians, and Georgians (less than 1 percent). Library of Congress, Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. "Ethnic Groups and Languages of Iran" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ According to the CIA World Factbook, the ethnic breakdown of Iran is as follows: Persian 61%, Azeri 16%, Kurd 10%, Lur 6%, Baloch 2%, Arab 2%, Turkmen and Turkic tribes 2%, other 1%. "The World Factbook – Iran". Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- 1 2 "Contemporary Iran : Economy, Society, Politics: Economy, Society, Politics - Google Books". Books.google.com. 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- 1 2 "World and Its Peoples - Marshall Cavendish". Books.google.com. 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- 1 2 Brenda Shaffer. The Limits of Culture: Islam and Foreign Policy MIT Press, 2006 ISBN 0262195291 p 229

- 1 2 Carl Waldman, Catherine Mason, Encyclopedia of European Peoples, pp.175

- ↑ Russell Contrera (2009-08-08). "Saving the people, killing the faith - News - Holland Sentinel - Holland, MI". Holland Sentinel. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ Ervand Abrahimian, "A History of Modern Iran", Cambridge University Press, 2008. Page 18: "Communal Composition of Iran, 1900 Persian 6 million Azeris 2.5 million Mazandaranis 200,000 Gilakis 200,000 Taleshis 20,000 Tatis 20,000"

- 1 2 "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- 1 2 3 "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ See Iran in Encyclopedia of Islam, Leiden. C.E. Bosworth (editor)

- 1 2 "Terror Free Tomorrow: Ahmadinejad Front Runner in Upcoming Presidential Elections;" (PDF). Terrorfreetomorrow.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ Archived 1 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Area handbook for Iran, Harvey Henry Smith, American University (Washington, D.C.), Foreign Area Studies, page 89

- ↑ Dalb, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. Columbia University Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-231-11568-7.

- ↑ Middle East Patterns: Places, Peoples, and Politics By Colbert C. Held, John Cummings, Mildred McDonald Held,2005, page 119.

- ↑ Colbert C. Held; John Cummings; Mildred McDonald Held (2005). Middle East Patterns: Places, Peoples, and Politics. p. 119

- ↑ "Iran Provinces". statoids.com.

- ↑ M. ʿAṭāʾī, “Gozāreš-e eqteṣādī dar bāra-ye berenj-e Gīlān wa sāyer-e ḡallāt-e ān/Economic Report on Rice and Other Cereals in Gilan,” Taḥqīqāt-e eqteṣādī 2/5-6, 1342 Š., pp. 64-148 (Pers. ed.), 1963, pp. 32-53 (Eng. ed.)

- ↑ Idem, “La culture du tabac dans le Gilân,” Stud. Ir. 9/1, 1980, pp. 121-30.

- ↑ Ehlers, “Die Teelandschaft von Lahidjan/Nordiran,” in Beiträge zur Geographie der Tropen and Subtropen. Festschrift für Herbert Wilhelmy, Tübingen, 1970, pp. 229-42

- ↑ [3] Bazin, Marcel. "GĪLĀN". Encyclopædia Iranica, X/VI, pp. 617-25. Retrieved 19 August 2014

- 1 2 "The Lurs of Iran". Cultural Survival. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- 1 2 "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ Edmonds, Cecil (2010). East and West of Zagros: Travel, War and Politics in Persia and Iraq 1913–1921. p. 188. ISBN 9789004173446.

- ↑ Gunter, Michael M. (2011). Historical Dictionary of the Kurds (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0810867512.

- ↑ Richard Frye,"The Golden age of Persia", Phoneix Press, 1975. Second Impression December 2003. pp 111: "Tribes always have been a feature of Persian history, but the sources are extremely scant in reference to them since they did not 'make' history. The general designation 'Kurd' is found in many Arabic sources, as well as in Pahlavi book on the deeds of Ardashir the first Sassanian ruler, for all nomads no matter whether they were linguistically connected to the Kurds of today or not. The population of Luristan, for example, was considered to be Kurdish, as were tribes in Kuhistan and Baluchis in Kirman"

- ↑ Tore Kjeilen (2008-08-19). "Talysh - LookLex Encyclopaedia". I-cias.com. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ Persian Wikipedia (تاتهای ایران)

- ↑ it is also spoken in some villages like Vafs and Chehreghan in the central areas of Iran like Gholamhossein Mosahab's The Persian Encyclopedia

- ↑ Paul, Ludwig (1998a). The position of Zazaki among West Iranian languages. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference of Iranian Studies, 11–15.09.1995, Cambridge, Nicholas Sims-Williams (ed.), 163–176. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

- ↑ Andrew Dalby, Dictionary of Languages: the definitive reference to more than 400 languages, Columbia University Press, 2004, pg 496.

- ↑ "Azari, the Old Iranian Language of Azerbaijan," Encyclopaedia Iranica, op. cit., Vol. III/2, 1987 by E. Yarshater

- ↑ "AZERBAIJAN vii. The Iranian Language of Azerb – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "TURKIC LANGUAGES OF PERSIA: AN OVERVIEW – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. 2010-04-15. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ Minorsky, V.; Minorsky, V. "(Azerbaijan). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill

- ↑ Elling, Rasmus Christian. Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-349-29691-0.

- ↑ "Azerbaijani". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ "Azerbaijani, South # A language of Iran". Ethnologue. 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ CIA, CIA. "CIA World Factbook". Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- ↑ Library of Congress, Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. "Ethnic Groups and Languages of Iran" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-12-02. 16% estimated in 2012

- ↑ "IRAN v. PEOPLES OF IRAN (1) A General Survey". Encyclopædia Iranica. March 29, 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ Library of Congress, Federal Research Division (March 2006). "Country Profile: Iran" (PDF). p. 5. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "Iran / Peoples". Looklex Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ "Results a new nationwide public opinion survey of Iran" (PDF). New America Foundation. 12 June 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ "Azeris". Minority Rights Group International. 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ Rasmus Christian Elling, Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Excerpt: "The number of Azeris in Iran is heavily disputed. In 2005, Amanolahi estimated all Turkic-speaking communities in Iran to number no more than 9 million. CIA and Library of congress estimates range from 16 percent to 24 percent – that is, 12–18 million people if we employ the latest total figure for Iran's population (77.8 million). Azeri ethnicsts, on the other hand, argue that overall number is much higher, even as much as 50 percent or more of the total population. Such inflated estimates may have influenced some Western scholars who suggest that up to 30 percent (that is, some 23 million today) Iranians are Azeris."

- 1 2 "Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini - Rasmus Christian Elling - Google Books". Books.google.com. 2013-02-19. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑

- Ali Gheissari, "Contemporary Iran:Economy, Society, Politics: Economy, Society, Politics", Oxford University Press, 2 April 2009. pg 300Azeri ethnonationalist activist, however, claim that number to be 24 million, hence as high as 35 percent of the Iranian population"

- Rasmus Christian Elling, Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Excerpt: "The number of Azeris in Iran is heavily disputed. In 2005, Amanolahi estimated all Turkic-speaking communities in Iran to number no more than 9 million. CIA and Library of congress estimates range from 16 percent to 24 percent -- that is, 12-18 million people if we employ the latest total figure for Iran's population (77.8 million). Azeri ethnicsts, on the other hand, argue that overall number is much higher, even as much as 50 percent or more of the total population. Such inflated estimates may have influenced some Western scholars who suggest that up to 30 percent (that is, some 23 million today) Iranians are Azeris."

- ↑ "Iran" (PDF). New America Foundation. 12 June 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ "Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009-03-09. (excerpt:"geographic region that comprises the extreme northwestern portion of Iran. It is bounded on the north by the Aras River, which separates it from independent Azerbaijan and Armenia; on the east by the Iranian region of Gīlān and the Caspian Sea; on the south by the Iranian regions of Zanjān and Kordestān; and on the west by Iraq and Turkey. Azerbaijan is 47,441 square miles (122,871 square km) in area.")

- ↑ Keith Stanley McLachlan, "The Boundaries of Modern Iran ", Published by UCL Press, 1994. pg 55

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Iranica, page 243 = accessed January 9, 2007

- ↑ Parviz Aḏkāʾi and EIr. "HAMADĀN i. GEOGRAPHY". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- 1 2 "زبانهاي رايج و نوع گويش در شهرستان". Governor of Hamadan. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- 1 2 "Country Study Guide-Azerbaijanis". STRATEGIC INFORMATION AND DEVELOPMENTS-USA. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Iran-Azerbaijanis". Library of Congress Country Studies. December 1987. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ "معرفی استان مرکزی". Office of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ↑ "Kordestān". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ↑ Bazin, Marcel. "GĪLĀN i. GEOGRAPHY AND ETHNOGRAPHY". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ Parviz Aḏkāʾi and EIr. "GILĀN xiv. Ethnic Groups". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ Michael Knüppel, E. "Turkic languages of persia". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- ↑ "AZERBAIJAN vi. Population and its Occupations and Culture". Encyclopædia Iranica. August 18, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ↑ "Tehran". Looklex Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2013-07-04.

- ↑ National Bibliography Number: 2887741 / plan review and assess the country's culture indicators (indicators Ghyrsbty) {report}: Tehran Province / General Council of the Order of the Executive Director is responsible for planning and policy: Mansoor Vaezi; run company experienced researchers Us - ISBN 978-600-6627-42-7 * Publication Status: Tehran - Institute Press book, published in 1391 * appearance: 296 p: table (the color), diagrams (colored part)

- ↑ "QAŠQĀʾI TRIBAL CONFEDERACY i. HISTORY – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20090718101816/http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/iran_081205.doc. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 Hooglund (2008), pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Hooglund (2008), pp. 100–101, 295.

- ↑ Hooglund (2008), p. 295.

- ↑ BetBasoo, Peter (1 April 2007). "Brief History of Assyrians". Assyrian International News Agency. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "Jewish Population of the World". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ "IRAN: Life of Jews Living in Iran". Sephardicstudies.org. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ "Conversion of Religious Minorities to the Bahá'í Faith in Iran". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ صابئین ایرانزمین، عکس: عباس تحویلدار، متن: مسعود فروزنده، آلن برونه، تهران: نشر کلید: ۱۳۷۹، شابک: 9789649064550، ص۸

- ↑ Contrera, Russell. "Saving the people, killing the faith – Holland, MI". The Holland Sentinel. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- ↑ "Iran Mandaeans in exile following persecution". Alarabiya.net. 2011-12-06. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- ↑ "Religions\publisher=Lexicorient.com". Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- 1 2 3 Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East Facts On File, Incorporated ISBN 143812676X p. 141

- ↑ P Bushkovitch, Princes Cherkasskii or Circassian Murzas, pp.12–13

- 1 2 "ČARKAS". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 "International Circassian Association". Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "ČARKAS". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Pierre, Oberling Georgians and Circassians in Iran

- ↑ "IRAN vii. NON-IRANIAN LANGUAGES (6) in Islamic Iran". Retrieved 28 April 2014.