Centralia, Illinois

| Centralia, Illinois | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| |

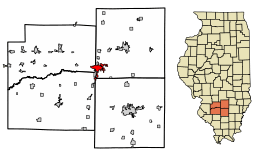

Location of Centralia in Clinton County, Illinois. | |

.svg.png) Location of Illinois in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 38°31′31″N 89°7′57″W / 38.52528°N 89.13250°WCoordinates: 38°31′31″N 89°7′57″W / 38.52528°N 89.13250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| Counties | Clinton, Jefferson, Marion, Washington |

| Townships |

Centralia, Brookside, Grand Prairie, Irvington |

| Founded | 1853[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Tom Ashby |

| Area[2] | |

| • Total | 9.23 sq mi (23.90 km2) |

| • Land | 8.19 sq mi (21.22 km2) |

| • Water | 1.03 sq mi (2.67 km2) |

| Elevation | 535 ft (163 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 13,032 |

| • Estimate (2016)[3] | 12,572 |

| • Density | 1,534.29/sq mi (592.36/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code(s) | 62801 |

| Area code(s) | 618 |

| FIPS code | 17-12164 |

| Wikimedia Commons | Centralia, Illinois |

| Website |

cityofcentralia |

Centralia is a city in Clinton, Jefferson, Marion, and Washington counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. The population was 13,032 as of the 2010 census,[4] down from 14,136 in 2000. The current mayor is Tom Ashby.

History

Centralia is named for the Illinois Central Railroad, built in 1853. The city was founded at the location where the two original branches of the railroad converged. Centralia was first chartered as a city in 1859.[1]

In the southern city limits is the intersection of the Third Principal Meridian and its baseline. This initial point was established in 1815, and it governs land surveys for about 60% of the state of Illinois, including Chicago.[5] The original monument is at the junction of Highway 51 and the Marion-Jefferson County Line Road; today there is a small easement situated in the northeast corner of this intersection, which contains a monument and historic marker.

Production of the PayDay candy bar began here in 1938. Michael Moore's documentary, The Big One (1998), opens with the closing of this candy bar plant in the late 20th century. It addresses similar economic woes in other cities.

The town of Centerville, Washington was renamed as Centralia, Washington to avoid being confused with another Centerville in that state. The suggestion came from a former resident of the Illinois town.

Geography

Centralia is located approximately 60 miles (97 km) east of St. Louis, Missouri. Most of the city, including its downtown, is in southwestern Marion County, but the city extends west into Clinton County and south 5 miles (8 km) into Washington and Jefferson counties. The city is 10 miles (16 km) north of exit 61 of Interstate 64 and 9 miles (14 km) west of exit 109 of Interstate 57. Centralia is one of three Illinois cities with portions in four counties, the others being Barrington Hills and Aurora. Because of its unique location within multiple counties, portions of Centralia are associated with different Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs). The Centralia Micropolitan Statistical Area includes all of Marion County. The Clinton County portion of the city is considered part of the St. Louis, MO–IL Metropolitan Statistical Area, while the Jefferson County portion lies within the Mt. Vernon Micropolitan Statistical Area. The portion of Centralia in Washington County is not considered part of any metropolitan or micropolitan area.

According to the 2010 census, Centralia has a total area of 9.223 square miles (23.89 km2), of which 8.19 square miles (21.21 km2) (or 88.8%) is land and 1.033 square miles (2.68 km2) (or 11.2%) is water.[6]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 3,190 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,621 | 13.5% | |

| 1890 | 4,763 | 31.5% | |

| 1900 | 6,721 | 41.1% | |

| 1910 | 9,680 | 44.0% | |

| 1920 | 12,491 | 29.0% | |

| 1930 | 12,583 | 0.7% | |

| 1940 | 16,343 | 29.9% | |

| 1950 | 13,863 | −15.2% | |

| 1960 | 13,904 | 0.3% | |

| 1970 | 15,966 | 14.8% | |

| 1980 | 15,126 | −5.3% | |

| 1990 | 14,274 | −5.6% | |

| 2000 | 14,136 | −1.0% | |

| 2010 | 13,032 | −7.8% | |

| Est. 2016 | 12,572 | [3] | −3.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[7] | |||

As of the census[8] of 2000, there were 14,136 people, 5,784 households, and 3,568 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,884.4 people per square mile (727.7/km²). There were 6,276 housing units at an average density of 836.6 per square mile (323.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 71.50% White, 25.34% African American, 0.25% Native American, 0.73% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.41% from other races, and 1.71% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.20% of the population.

There were 5,784 households out of which 28.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.1% were married couples living together, 14.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.3% were non-families. 34.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 17.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.95.

In the city the age distribution of the population shows 24.3% under the age of 18, 8.1% from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 22.2% from 45 to 64, and 19.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 80.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,905, and the median income for a family was $39,123. Males had a median income of $30,511 versus $21,967 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,174. About 11.2% of families and 14.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.1% of those under age 18 and 8.6% of those age 65 or over.

Mine incident

On March 25, 1947, the Centralia No. 5 coal mine explosion near the town killed 111 people.[9] The investigation team sent by the Mine Safety and Health Administration of the U.S. Department of Labor found that "a blownout shot of explosives that was stemmed with coal dust or an underburdened shot of explosions could have ignited the coal dust that was raised by preceding shots of explosions."[10]

- blown-out shot

- a blast in which the explosive action breaks little or no coal or rock

- underburdened

- insufficient burden of rock in relation to the explosive charge, resulting in a blown-out shot or a premature shot through shock of a neighboring charge of a blast pattern, often yielding less work than expected.

At the time of the explosion, 142 men were in the mine; 65 were killed by burns and other injuries, and 45 were killed by afterdamp. Eight men were rescued, but one died from the effects of afterdamp.

Song tributes

The story of the 1947 disaster is memorialized in folk singer Woody Guthrie's song "The Dying Miner".[9] Guthrie's recording of the song can be heard on the Smithsonian-Folkways CD recording Struggle (Smithsonian Folkways, 1990). Songwriter and labor scholar Bucky Halker recorded a very different arrangement of "Dying Miner" on his CD collection of Illinois labor songs Welcome to Labor Land (Revolting Records, 2002). Halker also recorded "New Made Graves of Centralia", a song he located on an obscure recording without the name of the author or recording artist. Halker's recording appears on his CD Don't Want Your Millions (Revolting Records, 2000).

Local features

Centralia's Foundation Park is a scenic 235-acre (0.95 km2) park that features hiking trails, an exercise trail, an ice skating pond and two fishing ponds stocked with bass, bluegill and catfish. The park also sports a restored prairie, a 27-hole disc-golf course, a Chapel in the Woods, the Hall Shelter, the Sentinel Shelter, The Bowl (an outdoor amphitheatre), Moose Oven, and the Miner's Memorial.

Foundation Park is the site of the annual Balloon Fest. Recent events have had about forty balloons and drew 40,000 visitors. The Annual Centralia Balloon festival was the event in which the second "Space Shuttle" hot air balloon was crashed due to a fuel line defect.

In addition to Foundation Park, the Centralia Foundation also supports the Centralia Carillon. Completed in 1983, with 65 bells, it is ranked as the eighth-largest in the world. The largest bell, Great Tom, weighs 5½ tons. The current Carillonneur is Roy Kroezen.

One of only two remaining 2500-class steam locomotives from the Illinois Central Railroad is preserved on static display at Centralia's Fairview Park. The locomotive is maintained by the Age of Steam Memorial non-profit organization.

Education

Centralia has a public school system, including Centralia High School. Its sports teams are called the Orphans and Annies. The Centralia boys basketball team won its 2,000th game during the 2007–08 season, making it the high school basketball team with the best record in the US. The Centralia Orphans were the State Runner-Up in the 2011 Class 3A.

The Orphans got their unique nickname during the early 1900s when the boy's basketball team made it to the state tournament. The school was low on funds at the time, and the team was forced to pick its uniforms from a pile of non-matching red uniforms. At the state tournament, an announcer commented that the team looked like a bunch of orphans on the court because of their mismatched uniforms. The name stuck. Previously, the team had gone by nicknames such as the Reds and Cardinals. In 2013 and 2014, the Centralia Orphans were recently named the Most Unique Mascot in the nation by USA Today.

The private Christ Our Rock Lutheran High School first opened its doors in August 2004 with nine students. As of 2013, the student body has grown to over 100 students. Christ Our Rock is the home of the Silver Stallions.[11]

Post-secondary education is available at Kaskaskia College, a community college serving the Centralia region.

Rail transportation

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Centralia. Amtrak Train 59, the southbound City of New Orleans, departs Centralia at 12:25 am daily with service to Carbondale, Fulton, Newbern-Dyersburg, Memphis, Greenwood, Yazoo City, Jackson, Hazlehurst, Brookhaven, McComb, Hammond, and New Orleans. Amtrak Train 58, the northbound City of New Orleans, departs Centralia at 4:10 am daily with service to Effingham, Mattoon, Champaign-Urbana, Kankakee, Homewood, and Chicago. Centralia is also served by Amtrak Train 390/391, the Saluki, daily in the morning, and Amtrak Train 392/393, the Illini, daily in the afternoon/evening. Both the Saluki and the Illini operate between Chicago and Carbondale.

Notable people

- Chad Beguelin, American playwright and four-time Tony Award nominee

- Warren Billhartz, state legislator, businessman, and lawyer

- David Blackwell, statistician and first black member of National Academy of Sciences

- James Brady, press secretary to President Ronald Reagan

- Roland Burris, Illinois Attorney General, comptroller, United States senator

- Brian Dinkelman, second baseman with the Minnesota Twins

- Dike Eddleman, small forward with the Tri-Cities Blackhakws/Milwaukee Hawks and Fort Wayne Pistons

- Bryan Eversgerd, pitcher with St. Louis Cardinals and coach

- Dwight Friedrich, state legislator and businessman

- Gary Gaetti, third baseman with the 1987 World Series champion Minnesota Twins and five other MLB teams

- Dick Garrett, guard with Southern Illinois and NBA's Los Angeles Lakers, Buffalo Braves, New York Knicks, and Milwaukee Bucks

- Mary Lee, actress

- Bobby Joe Mason, basketball player, Bradley University and Harlem Globetrotters[12]

- Ken "Preacher" McBride, Harlem Globetrotter[12]

- Gene Paulette, infielder for four Major League Baseball teams; born in Centralia

- Smiley Quick, golfer with the PGA Tour

- Kirk Rueter, pitcher for the San Francisco Giants

- Nancy Scranton, golfer with the LPGA Tour

- June C. Smith, Chief Justice of the Illinois Supreme Court

- Tom Wargo, golfer with the Senior PGA Tour

See also

References

- 1 2

- ↑ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jun 29, 2017.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Centralia city, Illinois". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ↑ "The Third Principal Meridian, Centralia Illinois". Principal Meridian Project. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ↑ "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 United States Mine Rescue Association. "Centralia No. 5 Mine Explosion, Centralia, Illinois". Mine Disasters in the United States. Retrieved 2018-06-25.

- ↑ Fanning, Fred, Public Sector Safety Professionals: Focused on Activity or Results? (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2014, retrieved 24 August 2012

- ↑ "Christ Our Rock Lutheran High School, Centralia, Illinois". Corlhs.org. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- 1 2 Harlem globetrotter all time roster. http://www.harlemglobetrotters.com/harlem-globetrotters-all-time-roster. Access date 5 June 2014

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Centralia, Illinois. |

- City of Centralia official website

- Centralia Tourism official website

- Greater Centralia Chamber of Commerce

- Centralia Balloon Fest

- Mine Safety and Health Administration page on the Centralia Mine Disaster

- Centralia Cultural Society

- Centralia Area Historical Society Museum

- Age of Steam Memorial

- Centralia onLine, community website

- Kaskaskia College

- Centralia High School