Ghazipur

Ghazipur (previously spelled Ghazipore, Ghauspur, and Ghazeepour), is a town in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. Ghazipur city is the administrative headquarters of the Ghazipur district, one of the four districts that form the Varanasi division of Uttar Pradesh. The city of Ghazipur also constitutes one of the five distinct tehsils, or subdivisions, of the Ghazipur district.

Ghazipur | |

|---|---|

City | |

The Tomb of Lord Cornwallis, Governor-General of British India | |

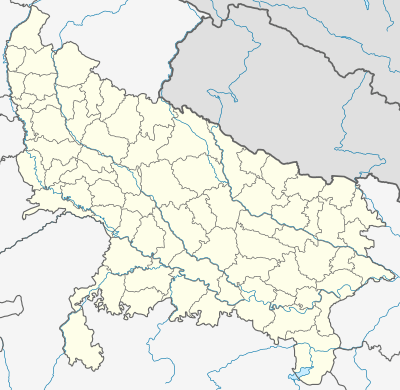

Ghazipur Location in Uttar Pradesh, India  Ghazipur Ghazipur (Uttar Pradesh) | |

| Coordinates: 25.58°N 83.57°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| District | Ghazipur |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Council |

| • Body | Ghazipur Municipal Council |

| • Chairman | sarita Agrawal |

| Area | |

| • Total | 20 km2 (8 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 121,136 |

| • Rank | 391 |

| • Density | 6,056/km2 (15,680/sq mi) |

| • Sex ratio | 902 ♀/♂ |

| Demonym(s) | Ghazipuri |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Hindi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 233001 |

| Telephone code | 91-548 |

| Vehicle registration | UP-61 |

| Website | www |

Ghazipur is well known for its opium factory, established by the British East India Company in 1820 and still the biggest legal opium factory in the world, producing the drug for the global pharmaceutical industry.[1] Ghazipur lies close to the Uttar Pradesh-Bihar border, about 80 km (50 mi) east of Varanasi and 50 km (31 mi) from Buxar, the entry point to Bihar state.

History

As per the verbal and folk history.[2] Ghazipur was covered with dense forest during the Vedic era and it was a place for ashrams of saints during that period. The place is related to the Ramayana period. Maharshi Jamadagni, the father of Maharshi Parashurama, is said to have resided here.[3] The famous Gautama Maharishi and Chyavana were given teaching and sermon here in ancient period. Lord Buddha gave his first sermon in Sarnath,[4] which is not far from the here.[5] Hsüan Tsang (629AD) has described name of this place in Chinese as Chen-Chu that stands for "lord of conflict or battle" as translation of Garjanpati, and its original name was Garzapur.[6] However some sources state that the original name was Gadhipur[7] in honour of Prince Gadhi (incarnation of Lord Indra).

A 30ft. high Ashoka Pillar is situated in Latiya, a village 30km away from the ghazipur city near Zamania Tehsil is a symbol of Mauryan Empire. It was declared a monument of national importance and protected by the archeological survey of India.[8] In the report of tours in that area of 1871-72 Sir Alexander Cunningham wrote, "The village receives its name from a stone lat, or monolith".[9]

First in India

The first Scientific Society of India was established first in Ghazipur in 1862 by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan for propagating modern Western knowledge of science, technology and industry. It was a departure from the past in the sense that education made a paradigm shift from traditional humanities and related disciplines to the new field of science and agriculture.[10] Some current institution like Technical Education and Research Institute (TERI),[11] part of post-graduate college PG College Ghazipur, in the city, takes their inspiration from that first Society.

Geography

Ghazipur is located at 25.58°N 83.57°E.[12] It has an average elevation of 62 metres (203 feet).

Rivers in the district include the Ganges, Gomati, Gaangi, Beson, Magai, Bhainsai, Tons and Karmanasa River.

Demographics

As per provisional data of 2011 census, Ghazipur urban agglomeration had a population of 121,136, out of which males were 63,689 and females were 57,447. Males constituted 52.57% of the population while females constituted 47.43% of the population. The literacy rate of Ghazipur urban agglomeration was 84.97% (higher than the national average of 74.04%) of which male literacy was 90.23% and female literacy was 79.17%.Sex ratio of Ghazipur urban agglomeration was found to be 902. Ghazipur urban agglomeration consist of Ghazipur, Kapoorpur, Mishrolia Madhopur, and Razdepur.[13]

As of 2011 India census,[14] Ghazipur city had a population of 110,698, out of which males were 58,126 and females were 52,572. Males constituted 52.5% of the population and females constituted 47.5% of the population. Ghazipur has an average literacy rate of 85.46% (higher than the national average of 74.04%) of which male literacy is 90.61% and female literacy is 79.79%. 11.46% of the population is under 6 years of age and the sex ratio is 904.

Places of interest

Sights in the city include several monuments built by Nawab Shaikh Abdulla, or Abdullah Khan, a governor of Ghazipur during the Mughal Empire in the eighteenth century, and his son. These include the palace known as Chihal Satun, or "forty pillars", which retains a very impressive gateway although the palace is in ruins, and the large garden with a tank and a tomb called the Nawab-ki-Chahar-diwari.[5][16]The road that starts at the Nawab-ki-Chahar-diwari tomb and runs past the mosque leads, after 10 km, to a matha devoted to Pavhari Baba.[5] The tank and tomb of Pahar Khan, faujdar of the city in 1580, and the plain but ancient tombs of the founder, Masud, and his son are also in Ghazipur, as is the tomb of Lord Cornwallis, one of the major figures of Indian and British history.[17] Cornwallis is famous for his role in the American Revolutionary War, and then for his time as Governor-General of India, being said to have laid the true foundation of British rule. He was later Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, there suppressing the 1798 Rebellion and establishing the Act of Union. He died in Ghazipur in 1805, soon after his returning to India for his second appointment as Governor-General. His tomb, overlooking the Ganges, is a heavy dome supported on 12 Doric columns above a cenotaph carved by John Flaxman.[16] The remains of an ancient mud fort also overlook the river, while there are ghats leading to the Ganges, the oldest of which is the ChitNath Ghat.[5][17]

Ghazipur opium factory

The opium factory located in the city was established by the British and continues to be a major source of opium production in India. It is known as the Opium Factory Ghazipur or, more formally, the Government Opium and Alkaloid Works. It is the largest factory of its kind in the country and indeed the world.[18] The factory was initially run by the East India Company and was used by the British during the First and Second Opium Wars with China.[1] The factory as such was founded in 1820 though the British had been trading Ghazipur opium before that. Nowadays its output is entirely above board, controlled legally by the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substance Act and Rules (1985) and administratively by the Indian government Ministry of Finance, overseen by a committee and a Chief Controller.[19] The factory's output serves the global pharmaceutical industry. Until 1943 the factory only produced raw opium extracts from poppies, but nowadays it also produces many alkaloids, having first begun alkaloid production during World War Two to meet military medical needs.[19] Its annual turnover is in the region of 2 billion rupees (approximately 36 or 37 million US dollars, for a profit of about 80 million rupees (1.5 million dollars).[19] It has been profitable every year since 1820, but the alkaloid production currently makes a loss, while the opium production makes a profit. The typical annual opium export from the factory to the US, for example, would be about 360 tonnes of opium.[19] As well as the opium and alkaloid production, the factory also has a significant R&D program, employing up to 50 research chemists.[19] It also serves the unusual role of being the secure repository for illegal opium seizures in India—and correspondingly, an important office of the Narcotics Control Bureau of India is located in Ghazipur.[19] Overall employment in the factory is about 900. Because it is a government industry, the factory is administrated from New Delhi but a General Manager oversees operations in Ghazipur.[19] In keeping with the sensitive nature of its production, the factory is guarded under high security (by the Central Industrial Security Force), and not easily accessible to the general public.[19] The factory has its own residential accommodation for its employees, and is situated across the banks of river Ganges from the main city of Ghazipur. It is surrounded by high walls topped with barbed wire. Its products are taken by high security rail to Mumbai or New Delhi for further export.[19]

The factory covers about 43 acres and much of its architecture is in red brick, dating from colonial times. Within the grounds of the factory there is a temple to Baba Shyam and a mazar, both said to predate the factory.[19] There is also a solar clock, installed by the British opium agent Hopkins Esor from 1911 to 1913.[19] Rudyard Kipling, who was familiar with opium both medicinally and recreationally,[20] visited the Ghazipur factory in 1888 and published a description of its workings in The Pioneer on 16 April 1888.[20] The text, In an Opium Factory is freely available from Adelaide University's ebook library.[21]

Amitav Ghosh's novel Sea of Poppies deals with the British opium trade in India and much of Ghosh's story is based on his research of the Ghazipur factory. In interview, Ghosh stresses how much of the wealth of the British Empire stemmed from the often unsavoury opium trade, with Ghazipur as one of its centers, but he is also amazed at the scale of the present-day operation.[18]

The Ghazipur Opium Factory may have one more claim to fame, for a rather unusual problem it has. It is infested with monkeys, but these are too narcotic-addled to be a real problem and workers drag them out of the way by their tails.[1][18][22]

Climate

| Climate data for Ghazipur (1981–2010, extremes 1978–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

34.1 (93.4) |

40.1 (104.2) |

45.1 (113.2) |

46.1 (115.0) |

46.4 (115.5) |

43.2 (109.8) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

30.8 (87.4) |

46.4 (115.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 13.9 (0.55) |

15.7 (0.62) |

7.2 (0.28) |

6.6 (0.26) |

23.2 (0.91) |

106.7 (4.20) |

306.9 (12.08) |

278.8 (10.98) |

215.9 (8.50) |

27.2 (1.07) |

7.5 (0.30) |

4.4 (0.17) |

1,014.1 (39.93) |

| Average rainy days | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 6.0 | 12.7 | 12.3 | 8.5 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 48.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 69 | 60 | 43 | 29 | 37 | 54 | 76 | 78 | 78 | 71 | 66 | 68 | 61 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[23][24] | |||||||||||||

Transport

Ghazipur Airport is situated in Ghazipur city. The airport is on the Ghazipur-Mau Road. Airports Authority of India (AAI) is the operator of this Airport.

Notable people

- Abbas Ansari, shooter, Indian politician

- Afzal Ansari, Indian politician, Member of Parliament 2004–2009, 2019–

- Mukhtar Ansari, Indian politician, 5 times MLA from Mau sadar

- Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, freedom fighter

- Lord Cornwallis, colonial administrator of North America, Ireland, and India died here

- Abdul Hamid, recipient of Param Veer Chakra, India's highest military award.

- Nazir Hussain, Bollywood actor and father of Bhojpuri cinema

- Shrawan Kumar, mathematics professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- George Marten, cricketer

- Kalraj Mishra Governor of Rajasthan

- Mahendra Nath Pandey, Member of Parliament, Minister for Skills Development

- Mangal Pandey, first hero sepoy, who raised the spark of freedom in India

- Sarjoo Pandey, freedom fighter

- Yunus Parvez, actor

- Dipendra Prasad, mathematics professor at TIFR - Mumbai

- Gopal Prasad, mathematics professor at University Of Michigan at Ann Arbor

- Kuber Nath Rai, writer and literary scholar

- Ram Bahadur Rai, Padmashri recipient

- Shivpujan Rai, freedom fighter, 1942

- Vinod Rai, Padma Bhushan recipient

- Viveki Rai, writer

- Moonis Raza, Vice Chancellor Delhi University and Co. Founder & Rector Jawaharlal Nehru University[25][26]

- Rahi Masoom Raza, author and poet[27]

- Sahajanand Saraswati, ascetic and leader

- Ram Badan Singh, Padma Bhushan recipient

- Manoj Sinha, Ex Member of Parliament, former State Minister of Communications and Minister of State for Railways in the Union Cabinet, Government of India[28]

- Dinesh Lal Yadav, singer and actor

See also

- List of educational institutes in Ghazipur

- National Waterway 1 (India)

References

- Paxman, Jeremy (2011). "Chapter 3". Empire:What Ruling the World Did to the British. London: Penguin Books.

- "Ghazipur That is known as Gadhipuri". Ghazipur.nic.in. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- Uttar Pradesh (India) (1982). Uttar Pradesh District Gazetteers: Ghazipur. Government of Uttar Pradesh. pp. 15–16.

- "Sarnath Buddhist Pilgrimage - Ticketed Monument - Archaeological Survey of India". Asi.nic.in. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "Places of Interest of District Ghazipur". Ghazipur.nic.in. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- Hsüan Tsang (629AD), Buddhist Records of the Western World, Vol 2 , Trübner's Oriental Series, 1884, TRUBNER & CO, LUDGATE, London, Page 61, Retrieved on 03 January 2017

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Ghazipur-India

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/p/019pho000001003u00683000.html

- "Sir Syed Ahmad Khan | Books". Sirsyedtoday.org. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "Technical Education & Research Institute". Teripgc.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

- "Falling Rain Genomics, Inc - Ghazipur". Fallingrain.com. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "Urban Agglomerations/Cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "Census 2011 Ghazipur". Census 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- Hunter, William Wilson (1908). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. XII. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 230–231.

- Führer, Alois Anton (1891). Archaeological Survey of India: The Monumental Antiquities and Inscriptions in the North-Western Province and Oudh. XII. Allahabad: Superintendent, Government Press. p. 231.

- "Opium financed British rule in India (interview with Amitav Ghosh)". BBC News. 23 June 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "A Visit to Gazipur Factory...A sea of surprise". Bihar Times. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Page, David (5 July 2008). John Radcliffe (ed.). "In an Opium Factory". The New Readers' Guide to the works of Rudyard Kipling. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Kipling, Rudyard (21 October 2012). Steve Thomas (ed.). "In an Opium Factory". eBooks@Adelaide, The University of Adelaide. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Bartholomew, Pablo. "The Opium Trail". Photo Essay on Cultivation of Opium in India. The Indian Economy Overview.

- "Station: Gazipur Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 287–288. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M215. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=158713

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.abhivyakti-hindi.org/sansmaran/2001/meriyadon.htm

- https://www.indiatoday.in/manoj-sinha