Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 (sometimes referred to as a single Act of Union 1801) were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The acts came into force on 1 January 1801, and the merged Parliament of the United Kingdom had its first meeting on 22 January 1801.

| |

| Long title | An Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland |

|---|---|

| Citation | 40 Geo. 3 c.38 |

| Introduced by | John Toler[1] |

| Dates | |

| Commencement | 1 January 1801 |

Status: Amended | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

Both acts remain in force, with amendments, in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland,[2] and have been repealed in the Republic of Ireland.[3]

Name

Two acts were passed in 1800 with the same long title, An Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland. The short title of the act of the British Parliament is Union with Ireland Act 1800, assigned by the Short Titles Act 1896. The short title of the act of the Irish Parliament is Act of Union (Ireland) 1800, assigned by a 1951 act of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, and hence not effective in the Republic of Ireland, where it was referred to by its long title when repealed in 1962.

Background

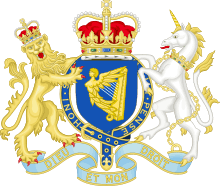

Before these Acts, Ireland had been in personal union with England since 1541, when the Irish Parliament had passed the Crown of Ireland Act 1542, proclaiming King Henry VIII of England to be King of Ireland. Since the 12th century, the King of England had been technical overlord of the Lordship of Ireland, a papal possession. Both the Kingdoms of Ireland and England later came into personal union with that of Scotland upon the Union of the Crowns in 1603.

In 1707, the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland were united into a single kingdom: the Kingdom of Great Britain. Upon that union, each House of the Parliament of Ireland passed a congratulatory address to Queen Anne, praying that, "May God put it in your royal heart to add greater strength and lustre to your crown, by a still more comprehensive Union".[4] The Irish Parliament at that time was subject to a number of restrictions that placed it subservient to the Parliament of England (and following the union of England and Scotland, the Parliament of Great Britain); however, Ireland gained effective legislative independence from Great Britain through the Constitution of 1782.

By this time access to institutional power in Ireland was restricted to a small minority, the Anglo-Irish of the Protestant Ascendancy, and frustration at the lack of reform among the Catholic majority eventually led, along with other reasons, to a rebellion in 1798, involving a French invasion of Ireland and the seeking of complete independence from Great Britain. This rebellion was crushed with much bloodshed, and the subsequent drive for union between Great Britain and Ireland that passed in 1800 was motivated at least in part by the belief that the rebellion was caused as much by reactionary loyalist brutality as by the United Irishmen.

Furthermore, Catholic emancipation was being discussed in Great Britain, and fears that a newly enfranchised Catholic majority would drastically change the character of the Irish government and parliament also contributed to a desire from London to merge the Parliaments.

Passing the Acts

Complementary acts had to be passed in the Parliament of Great Britain and in the Parliament of Ireland.

The Parliament of Ireland had recently gained a large measure of legislative independence under the Constitution of 1782. Many members of the Irish Parliament jealously guarded this autonomy (notably Henry Grattan) and a motion for union was legally rejected in 1799.

Only Anglicans were permitted to become members of the Parliament of Ireland, though the great majority of the Irish population were Roman Catholic, with many Presbyterians in Ulster. In 1793 Roman Catholics regained the right to vote if they owned or rented property worth £2 p.a. The Catholic hierarchy was strongly in favour of union, hoping for rapid emancipation and the right to sit as MPs – which was however delayed after the passage of the acts until 1829.

From the perspective of Great Britain, the union was desirable because of the uncertainty that followed the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and the French Revolution of 1789; if Ireland adopted Catholic Emancipation, willingly or not, a Roman Catholic Parliament could break away from Britain and ally with the French, while the same measure within a united kingdom would exclude that possibility. Also the Irish and British Parliaments, when creating a regency during King George III's "madness", gave the Prince Regent different powers. These considerations led Great Britain to decide to attempt merger of the two kingdoms and their Parliaments.

The final passage of the Act in the Irish Parliament was achieved with substantial majorities, in part according to contemporary documents through bribery, namely the awarding of peerages and honours to critics to get their votes.[5] Whereas the first attempt had been defeated in the Irish House of Commons by 109 votes against to 104 for, the second vote in 1800 produced a result of 158 to 115.[5]

Provisions

The Acts of Union were two complementary Acts, namely:

- The Union with Ireland Act 1800 (39 & 40 Geo. 3 c. 67),[6] an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and

- The Act of Union (Ireland) 1800 (40 Geo. 3 c. 38),[7] an Act of the Parliament of Ireland.

They were passed on 2 July 1800 and 1 August 1800 respectively, and came into force on 1 January 1801. They ratified eight articles which had been previously agreed by the British and Irish Parliaments:

- Articles I–IV dealt with the political aspects of the Union. It created a united parliament.

- In the House of Lords, the existing members of the Parliament of Great Britain were joined by, as Lords Spiritual, four bishops of the Church of Ireland, rotating among the dioceses in each session and as Lords Temporal 28 representative peers elected for life by the Peerage of Ireland.

- The House of Commons was to include the pre-union representation from Great Britain and 100 members from Ireland.

- Article V united the established Church of England and Church of Ireland into "one Protestant Episcopal Church, to be called, The United Church of England and Ireland"; but also confirmed the independence of the Church of Scotland.

- Article VI created a customs union, with the exception that customs duties on certain British and Irish goods passing between the two countries would remain for 10 years (a consequence of having trade depressed by the ongoing war with revolutionary France).

- Article VII stated that Ireland would have to contribute two-seventeenths towards the expenditure of the United Kingdom. The figure was a ratio of Irish to British foreign trade.

- Article VIII formalised the legal and judicial aspects of the Union.

Part of the attraction of the Union for many Irish Catholics was the promise of Catholic Emancipation, allowing Roman Catholic MPs, who had not been allowed in the Irish Parliament. This was however blocked by King George III who argued that emancipating Roman Catholics would breach his Coronation Oath, and was not realised until 1829.

The traditionally separate Irish Army, which had been funded by the Irish Parliament, was merged into the larger British Army.

The first Parliament

In the first Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the members of the House of Commons were not elected afresh. By royal proclamation authorised by the Act, all the members of the last House of Commons from Great Britain took seats in the new House, and from Ireland 100 members were chosen from the last Irish House of Commons: two members from each of the 32 counties and from the two largest boroughs, and one from each of the next 31 boroughs (chosen by lot) and from Dublin University. The other 84 Irish parliamentary boroughs were disfranchised; all were pocket boroughs, whose patrons received £15,000 compensation for the loss of what was considered their property.

Union Flag

.svg.png)

prior to the union with Ireland

incorporating the Irish Saint Patrick's Saltire

The flag, created as a consequence of the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1800, still remains the flag of the United Kingdom. Called the Union Flag, it combined the flags of St George's Cross (which was deemed to include Wales) and the St Andrew's Saltire of Scotland with the St Patrick's Saltire to represent Ireland (it now represents Northern Ireland).

References

Sources

- Primary

- Acts of Union – complete original text

- Text of the Act of Union (Ireland) 1800 (c.38) as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Text of the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Text of the Union with Ireland Act 1800 (c.67) as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Secondary

- Ward, Alan J. The Irish Constitutional Tradition: Responsible Government and Modern Ireland 1782–1992. Irish Academic Press, 1994.

- Lalor, Brian (ed). The Encyclopaedia of Ireland. Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, Ireland, 2003. ISBN 0-7171-3000-2, p7

Citations

- "Bill 4098: For the union of Great Britain and Ireland". Irish Legislation Database. Belfast: Queen's University. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- From legislation.gov.uk:

- "Act of Union (Ireland) 1800". Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "Union with Ireland Act 1800". Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- From Irish Statute Book:

- "Statute Law Revision (Pre-Union Irish Statutes) Act, 1962, Schedule". Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "Statute Law Revision Act, 1983, Schedule Part III: English and British Statutes Extended to Ireland, 1495-1800". Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Journals of the Irish Commons, vol. iii. p. 421

- Alan J. Ward, The Irish Constitutional Tradition p.28.

- "Union with Ireland Act 1800". No. (39 & 40 Geo. 3 c. 67) of 2 July 1800. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Act of Union (Ireland) 1800". No. (40 Geo. 3 c. 38) of 1 August 1800. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

Further reading

- Kelly, James. "The origins of the act of union: an examination of unionist opinion in Britain and Ireland, 1650-1800." Irish Historical Studies 25.99 (1987): 236–263.

- Keogh, Dáire, and Kevin Whelan, eds. Acts of Union: The causes, contexts, and consequences of the Act of Union (Four Courts Press 2001).

- McDowell, R. B. Ireland in the Age of Imperialism and Revolution, 1760-1801 (1991) pp 678–704.

External links

- Act of Union Virtual Library from Queen's University Belfast

- Ireland - History - The Union,1800/Ireland - Politics and government - 19th century index of documents digitised by Enhanced British Parliamentary Papers On Ireland

- Digital Reproduction of the Original Act (39&40 Geo. 3 c. 67) on the Parliamentary Archives catalogue

.svg.png)