Whakatane

| Whakatane Whakatāne (Māori) | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

| |

| Motto(s): Sunshine Capital of New Zealand | |

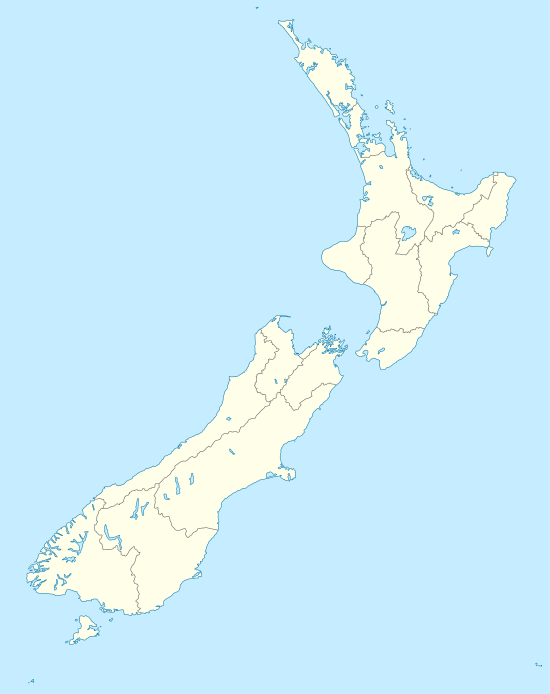

Whakatane Location of Whakatane | |

| Coordinates: 37°59′S 177°00′E / 37.983°S 177.000°ECoordinates: 37°59′S 177°00′E / 37.983°S 177.000°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Bay of Plenty |

| Territorial authority | Whakatane District |

| Settled by Māori | c. 1200 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Tony Bonne |

| • Deputy Mayor | Judy Turner |

| Area | |

| • Territorial | 4,442.07 km2 (1,715.09 sq mi) |

| Population (June 2018)[1] | |

| • Territorial | 35,700 |

| • Density | 8.0/km2 (21/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 19,750 |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| Postcode(s) | 3120 |

| Area code(s) | 07 |

| Website | http://www.whakatane.govt.nz/ |

Whakatane (/fɑːkɑːˈtɑːnə/ fah-ka-TAH-ne, alt. /ˌwɒkəˈtɑːni/; Māori: Whakatāne, Māori pronunciation: [fakaˈtaːnɛ]) is a town in the eastern Bay of Plenty Region in the North Island of New Zealand, 90 km east of Tauranga and 89 km north-east of Rotorua, at the mouth of the Whakatane River. Whakatane District is the encompassing territorial authority, which covers an area to the south and west of the town, excluding the enclave of Kawerau.

Whakatane has an urban population of 19,750, making it New Zealand's 24th largest urban area, and the Bay of Plenty's third largest urban area behind Tauranga and Rotorua. Another 15,950 people live in the rest of the Whakatane District. Around 40% of the district's population have Māori ancestry. The District has a land area of 4,442.07 km2 (1,715.09 sq mi). Whakatane District was created in 1976.

Whakatane forms part of the parliamentary electorate of East Coast, represented by Anne Tolley of the New Zealand National Party. It is the main urban centre of the Eastern Bay Of Plenty sub-region; incorporating Whakatane, Kawerau, and Opotiki, the Eastern Bay stretches from Otamarakau in the west, to Cape Runaway in the north-east and Whirinaki in the south. It is the seat of the Bay of Plenty Regional Council, chosen as a compromise between the region's two larger cities, Tauranga and Rotorua.

History

Māori occupation

The site of the town has long been populated. Māori pā (Māori fortified village) sites in the area date back to the first Polynesian settlements, estimated to have been around 1200 CE. According to Māori tradition Toi-te-huatahi, later known as Toi-kai-rakau, landed at Whakatane about 1150 CE in search of his grandson Whatonga. Failing to find Whatonga, he settled in the locality and built a pa on the highest point of the headland now called Whakatane Heads, overlooking the present town. Some 200 years later the Mataatua waka landed at Whakatane.[2]

The Maori name "Whakatāne" is reputed to commemorate an incident occurring after the arrival of the Mataatua. The men had gone ashore and the canoe began to drift. Wairaka, a chieftainess, said “Kia Whakatāne au i ahau” (“I will act like a man”), and commenced to paddle (which women were not allowed to do), and with the help of the other women saved the canoe.[3]

The region around Whakatane was important during the New Zealand Wars of the mid 19th century, particularly the Volkner Incident. Its role culminated in 1869 with raids by Te Kooti's forces and a number of its few buildings were razed, leading to an armed constabulary being stationed above the town for a short while. Whakatane beach heralded an historic meeting on 23 March 1908 between Prime Minister Joseph Ward and the controversial Māori prophet and activist Rua Kenana Hepetipa. Kenana claimed to be Te Kooti's successor.

European settlement

The town was a notable shipbuilding and trade centre from 1880 and with the draining of the Rangitikei swamp into productive farmland from 1904, Whakatane grew considerably. In the early 1920s it was the fastest growing town in the country for a period of about three years and this saw the introduction of electricity for the first time. The carton board mill at Whakatane began as a small operation in 1939[4] and continues operating to this day.

The Whakatane River once had a much longer and more circuitous route along the western edge of the Whakatane urban area, having been significantly re-coursed in the 1960s with a couple of its loopier loops removed to help prevent flooding and provide for expansion of the town. Remnants of the original watercourse remain as Lake Sullivan and the Awatapu lagoon. The original wide-span ferro-concrete bridge constructed in 1911 at the (aptly named) Bridge Street was demolished in 1984 and replaced by the Landing Road bridge.[5]

Whakatane has in recent years benefited from its relative dominance over numerous smaller and less prosperous towns surrounding it, such as Te Teko (affectionately known as 'Texas') and Waimana, and its popularity as a retirement and lifestyle destination.

Mataatua Declaration

The 'First International Conference on the Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples' was held in Whakatane from 12 to 18 June 1993. This resulted in the Mataatua Declaration on Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples', commonly referred to as the Mataatua Declaration.[6]

Climate

| Climate data for Whakatane, New Zealand | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24 (75) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

21 (70) |

18 (64) |

15 (59) |

15 (59) |

15 (59) |

17 (63) |

19 (66) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

20 (67) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19 (66) |

19 (66) |

18 (64) |

15 (59) |

12 (54) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

14 (57) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

14 (58) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14 (57) |

14 (57) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

5 (41) |

4 (39) |

5 (41) |

7 (45) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

9 (49) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 111 (4.37) |

100 (3.94) |

142 (5.59) |

108 (4.25) |

124 (4.88) |

148 (5.83) |

134 (5.28) |

153 (6.02) |

131 (5.16) |

116 (4.57) |

119 (4.69) |

149 (5.87) |

1,535 (60.43) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248.0 | 197.8 | 186.0 | 180.0 | 155.0 | 150.0 | 155.0 | 155.0 | 180.0 | 217.0 | 210.0 | 217.0 | 2,250.8 |

| Source #1: The Weather Network[7]

<-- --> | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: World Climate Guide[8] | |||||||||||||

Whakatane has frequently recorded the highest annual sunshine hours in New Zealand (year and respective sunshine hours shown below);

2008 - 2703hrs

2010 - 2561hrs

2012 - 2602hrs

2013 - 2792hrs

2014 - 2710hrs

2015 - 2785hrs

Official recording began in 2008. The town recorded an average of over 7.5hrs of sunshine a day in 2013[9] Whakatane also records the national daily high (temp) on approximately 55 days of the year.[10]

Natural Disasters

Whakatane was affected by the 1987 Edgecumbe earthquake. Heavy rain struck the Bay of Plenty and Whakatane on 16–18 July 2004 causing severe flooding and resulting in a state of civil emergency being declared. Many homes and properties were flooded, forcing thousands of Whakatane residents to evacuate. The Rangitaiki River burst its banks, flooding large areas of farmland, and numerous roads were closed by floods and slips. A total of 245.8 mm of rain fell in Whakatane in the 48-hour period and many small earthquakes were also felt during this time, loosening the sodden earth and resulting in landslips that claimed two lives.

Geography

Moutohora Island is a small island off the Bay of Plenty coast about 12 kilometres north of Whakatane. The island has numerous sites of pā. It also provided shelter for James Cook's Endeavour in 1769. A whaling station existed on the island during the 19th century.

Whakaari/White Island is an active marine volcano located 48 kilometres offshore of Whakatane and a popular visitor attraction. Sulphur mining on the island was attempted but abandoned in 1914 after a lahar killed all 10 workers.

The mouth of the Whakatane River and Ohiwa Harbour have both provided berths for yachts, fishing trawlers and small ships since European settlement of the area. Nearby Ohope Beach is a sandy beach stretching 11 km (7 mi) from the Ohiwa Harbour entrance.

Industries and tourism

The town's main industries are diverse: forestry, tourism, agriculture, horticulture, fishing and manufacturing are all well-established. There is a large carton board packaging mill, a newspaper press, and a brewery.

While farming and forestry activities remain the dominant sectors, tourism is a growing industry for Whakatane, with a continued increase in guest nights in the district.[11] White Island is a key attraction. Popular tourist activities include the beaches, swimming with dolphins, whale watching, chartered fishing cruises, surf tours, amateur astronomy, hunting, experiences of Maori culture and bush walking. Whakatane is also used as a base for many tourists who wish to explore other activities in the surrounding region.

Aquaculture is an emerging industry for the Eastern Bay, with the development of a 3800 hectare marine farm 8.5 km offshore of Opotiki, expected to produce 20,000 tonnes of mussels per annum by 2025 and add $35 million to regional GDP.[12] Whakatane is home to the regional radio station One Double X - 1XX - one of the first privately owned commercial radio stations on air in New Zealand in the early 1970s.

Whakatane has become the dominant commercial service centre for the Eastern Bay. In 2006, a large-format shopping centre (The Hub Whakatane) was built on the edge of town anchored by national chains Bunnings Warehouse and Harvey Norman. Its retail space totals 24,000sqm and includes 900 car parks.[13] Prior to the centre's construction, it was estimated around $30 million in local retail spending was being lost to large format retail stores in neighboring Tauranga and Rotorua.

Infrastructure

Whakatane Airport is served by Air Chathams and Sunair Aviation, with direct flights using DC 3 Dakota and Metroliner 3 aircraft to Auckland, and on-request flights to Gisborne and Hamilton. Air New Zealand previously operated the Auckland service until April 2015.[14] Private cars, limited public transport and taxis (as well as cycling and walking) are the primary modes of transport for residents. A regular public bus service runs between Whakatane and Ohope. Once daily return bus services operate to Tauranga, en route from Kawerau and Opotiki on alternate weekdays.

Whakatane sits at the confluence of State Highway 30. State Highway 2 bypasses the urban area.

There are two secondary schools in Whakatane, and a Maori tertiary institute- Te Whare Wananga O Awanuiarangi.

Marine

Coastal trading, including scows and steamships- notably the Northern Steamship Company service, which ran until 1959, used Whakatane as a port of call. Today it primarily services charter vessels, commercial & recreational fishing vessels. The depth of water over the Whakatane River entrance has been a limiting factor to the development of better port facilities, but it is generally held that a training wall along the western edge of the entrance would allow greater depths and safer crossings.

Rail

A passenger train called the Taneatua Express ran on the East Coast Main Trunk Railway (ECMT) as far as Taneatua until 1959. The Taneatua Branch line was formerly part of the ECMT and connected with the current ECMT at Hawkens Junction.

A private railway line operated by Whakatane Board Mills (now Carter Holt Harvey Whakatane) formerly connected the company's mill on the western side of the river to the Taneatua Branch line at Awakeri. The Whakatane Board Mills Line was freight only, with no passenger service. In 1999 operation of the Whakatane Board Mills line was taken over by Tranz Rail (now KiwiRail) and the line was renamed the Whakatane Industrial line. The line has since been closed and lifted, and the Taneatua Branch line is used for tourist excursions.

Sister cities

Whakatane has a friendship agreement with Shibukawa, Gunma, Japan.[16]

Notable people

- Alexander Peebles (1856–1934), first chairman of the Whakatane County Council in 1900[17]

- Albert Oliphant Stewart (1884–1958), tribal leader and local politician[18]

- Benji Marshall NZ rugby league and rugby union player

- Ian Shearer New Zealand politician

- Mike Moore NZ politician and Prime Minister

- Margaret Mahy New Zealand author

- Lindy Chamberlain New Zealand-Australian woman wrongly convicted in one of Australia's most publicised murder trials.

- Lisa Carrington New Zealand flatwater canoer

- Sarah Walker New Zealand BMX racer

- Eve Rimmer New Zealand paraplegic Athlete

- Rex Patrick Australian politician

References

- ↑ "Subnational Population Estimates: At 30 June 2018 (provisional)". Statistics New Zealand. 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018. For urban areas, "Subnational population estimates (UA, AU), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996, 2001, 2006-18 (2018 boundary)". Statistics New Zealand. 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ↑ McLintock, A. H. (1966). "An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand". Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ "The legend of Wairaka and the naming of Whakatane". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ↑ "Whakatane Board Mill".

- ↑ Skelton, H (2002) Pictures from the Past- Bay of Plenty, Volcanic Plateau & Gisborne. Wyatt and Wilson Print, Christchurch. ;pg 76.

- ↑ "The Mataatua Declaration on Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples" (PDF). Ngati Awa. June 1993. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ "Climate Statistics for Whakatane, New Zealand". Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ↑ "Whakatane Climate Guide, New Zealand". Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Bonne, Tony. "Whakatane – NZ's sunshine capital". Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ http://www.whakatane.com/visitor-information/weather

- ↑ "Whakatane Tourism Numbers positive". Sunlive. 20 Mar 2015.

- ↑ Halford, B. "Auditors report on the Opotiki Long Term Plan 2012-2022". Audit New Zealand.

- ↑ "The Hub Whakatane". McDougall Reidy. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ "Air NZ announces regional network cuts". Stuff.co.nz. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "International Exchange". List of Affiliation Partners within Prefectures. Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". Whakatane District Council. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Heath, Alison B. "Alexander Peebles". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ Haami, Bradford. "Albert Oliphant Stewart". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 April 2017.