Thwaites Glacier

.jpg)

Thwaites Glacier (75°30′S 106°45′W / 75.500°S 106.750°W) is an unusually broad and fast Antarctic glacier flowing into Pine Island Bay, part of the Amundsen Sea, east of Mount Murphy, on the Walgreen Coast of Marie Byrd Land.[1] Its surface speeds exceed 2 km/yr near its grounding line, and its fastest flowing grounded ice is centred between 50 and 100 km east of Mount Murphy. It was named by ACAN[2] after Fredrik T. Thwaites, a glacial geologist, geomorphologist and professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[3] Thwaites Glacier drains into West Antarctica’s Amundsen Sea and is closely watched for its potential to raise sea levels.

Along with Pine Island Glacier, Thwaites Glacier has been described as part of the "weak underbelly" of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, due to its apparent vulnerability to significant retreat. This hypothesis is based on both theoretical studies of the stability of marine ice sheets and recent observations of large changes on both of these glaciers. In recent years, the flow of both of these glaciers have accelerated, their surfaces lowered, and the grounding lines retreated.

Research

In 2011, using geophysical data collected from flights over Thwaites Glacier (data collected under NASA's Ice Bridge campaign), a study by scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory showed a rock feature, a ridge 700 meters tall that helps anchor the glacier and helped slow the glacier's slide into the sea. The study also confirmed the importance of seafloor topography in predicting how the glacier will behave in the near future.[4] However, the glacier has been considered to be the biggest threat on relevant time scales, for rising seas, current studies aim to better quanitfy retreat and possible impacts.[5]

Water drainage beneath the glacier

Swamp-like canal areas and streams underlie the glacier. The upstream swamp canals feed streams with dry areas between the streams which retard flow of the glacier. Due to this friction the glacier is considered stable in the short term.[6]

Predictions

A University of Washington study, using satellite measurements and computer models, determined that the Thwaites Glacier will gradually melt, leading to an irreversible collapse over the next 200 to 1000 years.[7][8][9][10][11]

Features and observation

Thwaites Glacier Tongue

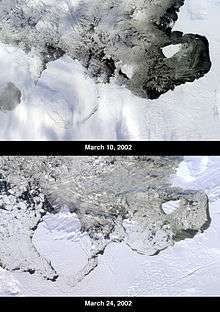

The Thwaites Glacier Tongue, or Thwaites Ice Tongue (75°0′S 106°50′W / 75.000°S 106.833°W), is about 50 km wide and has progressively shortened due to ice calving, based on the observational record. It was initially delineated from aerial photographs collected during Operation Highjump in January 1947.

On 15 March 2002, the National Ice Center reported that an iceberg named B-22 broke off from the ice tongue. This iceberg was about 85 km long by 65 km wide, with a total area of some 5,490 km². As of 2003, B-22 had broken into five pieces, with B-22A still in the vicinity of the tongue, while the other smaller pieces had drifted farther west.

Thwaites Iceberg Tongue

The Thwaites Iceberg Tongue (74°0′S 108°30′W / 74.000°S 108.500°W) was a large iceberg tongue which was aground in the Amundsen Sea, about 32 km northeast of Bear Peninsula. The feature was about 112 km long and 32 km wide, and in January 1966 its southern extent was only 5 km north of Thwaites Glacier Tongue. It consisted of icebergs which had broken off from the Thwaites Ice Tongue and ran aground, and should not be confused with the latter, which is still attached to the grounded ice. It was delineated by the USGS from aerial photographs collected during Operation Highjump and Operation Deepfreeze.[12] It was first noted in the 1930s, but finally detached from the ice tongue and broke up in the late 1980s.[13][14]

See also

References

- ↑ "Thwaites Glacier: Antarctica, name, geographic coordinates, description, map". Geographic.org. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ↑ "Thwaites Glacier Tongue". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Thwaites Glacier". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ http://www.earth.columbia.edu/articles/view/2904

- ↑ "This Antarctic glacier is the biggest threat for rising sea levels. The race is on to understand it". The Washingtoin Post. October 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Scientists Image Vast Subglacial Water System Underpinning West Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier". University of Texas. July 9, 2013. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Irreversible collapse of Antarctic glaciers has begun, studies say". Los Angeles Times. May 12, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ↑ Sumner, Thomas (April 8, 2016). "Changing climate: 10 years after An Inconvenient Truth". Science News. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet after local destabilization of the Amundsen Basin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112: 14191–14196. doi:10.1073/pnas.1512482112. PMC 4655561.

- ↑ "Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith, and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011". Geophysical Research Letters. 41: 3502–3509. doi:10.1002/2014GL060140.

- ↑ "Marine Ice Sheet Collapse Potentially Under Way for the Thwaites Glacier Basin, West Antarctica". Science. 344: 735–738. doi:10.1126/science.1249055.

- ↑ "Thwaites Iceberg Tongue". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Reynolds, Larry (4 March 2000). "Where a cold tongue isn't". Teachers Experiencing Antarctica. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ Lucchitta, B.K.; Smith, C.E.; Bowel, J.; Mullins, K.F. (1994). "Velocities and mass balance of Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica, derived from ERS-1 SAR". Pub. SP-361, 2nd ERS-1 Symposium, Space at the Service of Our Environment, Hamburg, Germany, 11–14, Oct. 1993 Proceedings. pp. 147–151.