Thai Chinese

Visitors at Wat Mangkon Kamalawat, one of the most prominent Chinese Buddhist temples in Thailand | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

10,349,900 (est) Thais of at least partial Chinese descent (around 50 percent of the Thai population) (2012)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Bangkok, Chanthaburi, Phuket, Trang, Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Nan, Hat Yai, Songkhla, Surat Thani, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Udon Thani, Khon Kaen, Ubon Ratchathani, Nakhon Phanom, Sakon Nakhon | |

| Languages | |

|

Thai, Southern Thai, Isan and Northern Thai historically Southern Min (Teochew and Hokkien), Hainanese, Hakka and Cantonese | |

| Religion | |

|

Predominantly Theravada Buddhism minorities Mahayana Buddhism, Chinese folk religion and Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Thais Peranakan • Southern Chinese Overseas Chinese |

| Thai Chinese | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 泰國華僑 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 泰国华侨 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 泰國華人 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 泰国华人 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Thai of Chinese origin, often called Thai Chinese, consist of Thai people of full or partial Chinese ancestry—particularly the Han Chinese. Thailand is home to the largest overseas Chinese community in the world with a population of approximately 10 million people, accounting for 14 percent of the total Thai population as of 2012. It is also the oldest and most prominent integrated overseas Chinese community. Slightly more than half of the ethnic Chinese population in Thailand trace their ancestry to eastern Guangdong Province. This is evidenced by the prevalence of the Southern Min Chaozhou dialect among the Chinese in Thailand. A minority trace their ancestry to Hakka and Hainanese immigrants.[3]

The Thai Chinese have been deeply ingrained into all elements of Thai society over the past 200 years. The present Thai royal family, the Chakri Dynasty, was founded by King Rama I who himself was partly Chinese. His predecessor, King Taksin of the Thonburi Dynasty, was the son of a Chinese immigrant from Guangdong Province and a Thai mother. With the highly successful integration of historic Chinese immigrant communities throughout Thailand, a significant number of Thai Chinese are the descendants of intermarriages between Chinese immigrants and native Thais. Many Thai Chinese have assimilated into Thai society and self-identify solely as Thai.[4][5]

Thai Chinese are a well established middle class ethnic group and are well represented in all levels of Thai society.[6][7][8][9][10] Thai Chinese also play a leading role in Thailand's business sector and dominate the Thai economy today.[11][12][13][14] In addition, Thai Chinese have a strong presence in Thailand's political scene with most of Thailand's former Prime Ministers and the majority of parliament having at least some Chinese ancestry.[15][16][17]

Demographics

Thailand has the largest overseas Chinese community in the world outside of China and Taiwan.[18] Fourteen percent of Thailand's population is considered ethnic Chinese.[19] One Thai academic of Chinese origin claims the share of those having at least partly Chinese ancestry is estimated at about 40 percent,[2] but without an accurate census or nationwide DNA testing, there is no credible evidence to support this theory.[2]

Identity

For assimilated second- and third-generation Thai Chinese and even some first-generation immigrants, it has remained principally a personal choice whether or not a Thai person of Chinese descent chooses to identify himself as ethnic Chinese.[20] Nonetheless, nearly all Thai Chinese sole self-identify as Thai, due to their close integration and successful assimilation into Thai society.[21][22] G William Skinners observed that the level of assimilation of the descendants of Chinese immigrants in Thailand disproved the "myth about the 'unchanging Chinese'", noting that "assimilation is considered complete when the immigrant's descendant identifies himself in almost all social situations as a Thai, speaks Thai language habitually and with native fluency, and interacts by choice with Thai more often than with Chinese." [23] Skinners believed that the assimilation success of the Thai Chinese was a result of the wise policy of the Thai rulers who, since the 17th century, allowed able Chinese tradesmen to advance their ranks into the kingdom's nobility.[24] The rapid and successful assimilation of the Thai Chinese has been celebrated by the Chinese descendants themselves, as evident in contemporary literature such as the novel Letters from Thailand (Thai: จดหมายจากเมืองไทย) by Botan.[25]

Today, the Thai Chinese constitute a significant part of the royalist/nationalist movements. When the then prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra (who is a Thai Chinese) was ousted from power in 2006, it was Mr. Sondhi Limthongkul, another prominent Thai Chinese businessman, who formed and led People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) movement to overthrow the Thaksin government. Mr. Sondhi accused Mr. Thaksin of corruption based on improper business ties between MR. Thaksin's corporate empire and the Singapore-based Temasek Holdings Group.[26] The Thai Chinese in and around Bangkok were also the main participants of the months-long political campaign against the government of Ms. Yingluck (Mr. Thaksin's sister), between November 2013 and May 2014, the event which culminated in the military takeover in May 2014.

History

Han Chinese traders, mostly from Fujian and Guangdong, began arriving in Ayutthaya by at least the 13th century. According to the Chronicles of Ayutthaya, King Ekathotsarot (r. 1605–1610) had been "concerned solely with ways of enriching his treasury," and was "greatly inclined toward strangers and foreign nations," especially Portugal, Spain, the Philippines, China, and Japan.

Ayutthaya was under almost constant Burmese threat from the 16th century onward, and the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty was alarmed by Burmese military might. From 1766-1769, the Qianlong Emperor sent his armies four times to subdue the Burmese, but the Sino-Burmese Wars ended in complete failure, and Ayutthaya fell in the Burmese–Siamese War (1765–1767). However, the Chinese efforts did divert the attention of Burma's Siam army. General Taksin, himself the son of a Chinese immigrant, took advantage of this to organize his force and attack the Burmese invaders. When he became king, Taksin actively encouraged Chinese immigration and trade. Settlers mainly from Chaozhou prefecture came to Siam in large numbers.[27] Immigration continued over the following years, and the Chinese population in Thailand jumped from 230,000 in 1825 to 792,000 by 1910. By 1932, approximately 12.2 percent of the population of Thailand was Chinese.[28]

The early Chinese immigration consisted almost entirely of men who did not bring women. Therefore, it became common for male Chinese immigrants to marry local Thai women. The children of such relationships were called Sino-Thai[29] or luk-jin (ลูกจีน) in Thai.[30] These Chinese-Thai intermarriages declined somewhat in the early 20th century, when significant numbers of Chinese women also began immigrating to Thailand.

The corruption of the Qing Dynasty and the massive population increase in China, along with very high taxes, caused many men to leave China for Thailand in search of work. If successful, they sent money back to their families in China. Many Chinese immigrants prospered under the "tax farming" system, whereby private individuals were sold the right to collect taxes at a price below the value of the tax revenues.

In the late 19th century, when Thailand was struggling to defend its independence from the colonial powers, Chinese bandits from Yunnan Province began making raids into the country in the Haw Wars (Thai: ปราบกบฏฮ่อ). Thai nationalist attitudes at all levels were thus colored by anti-Chinese sentiment. Members of the Chinese community had long dominated domestic commerce and had served as agents for royal trade monopolies. With the rise of European economic influence, however, many Chinese shifted to opium trafficking and tax collecting, both of which were despised occupations.

From 1882 to 1917, nearly 13,000 to 34,000 Chinese entered the country per year from southern China which was vulnerable to floods and drought, mostly settling in Bangkok and along the coast of the Gulf of Siam. They predominated in occupations requiring arduous labor, skills, or entrepreneurship. They worked as blacksmiths, railroad laborers, and rickshaw pullers. While most Thais were engaged in rice production, the Chinese brought new farming ideas and new methods to supply labor on its rubber plantations, both domestically and internationally.[31] However, republican ideas brought by the Chinese were considered seditious by the Thai government. For example, a translation of Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People was banned under the Communism Act of 1933. The government had regulated Chinese schools even before compulsory education was established in the country, starting with the Private Schools Act of 1918. This act required all foreign teachers to pass a Thai language test, and for principals of all schools to implement standards set by the Thai Ministry of Education.[32]

Legislation by King Rama VI (1910–1925) that required the adoption of Thai surnames was largely directed at the Chinese community as a number of ethnic Chinese families left Burma between 1930 and 1950 and settled in the Ratchaburi and Kanchanaburi Provinces of western Thailand. A few of the ethnic Chinese families in that area had already emigrated from Burma in the 19th century.

The Chinese in Thailand also suffered discrimination between the 1930s to 1950s under the military dictatorship of Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram (in spite of having part-Chinese ancestry himself),[33] which allied itself with the Empire of Japan. The Primary Education Act of 1932 made the Thai language the compulsory medium of education, but as a result of protests from Thai Chinese, by 1939, students were allowed two hours per week of Mandarin instruction.[32] State corporations took over commodities such as rice, tobacco, and petroleum, and Chinese businesses found themselves subject to a range of new taxes and controls. By 1970, more than 90 percent of the Chinese born in Thailand had abandoned Chinese citizenship and were granted Thai citizenship instead. In 1975, diplomatic relations were established with China.[34]

Culture

Intermarriage with the Thais has resulted in many people who claim Thai ethnicity with Chinese ancestry, or mixed.[35] People of Chinese descent are concentrated in the coastal areas of Thailand, principally Bangkok and Paknampho( Nakhonsawan ).[36] Considerable segments of Thailand's economic, political, and academic elite are of Chinese descent.[2]

Language

Today, nearly all ethnic Chinese in Thailand speak Thai exclusively. Only elderly Chinese immigrants still speak their native varieties of Chinese. The fast and successful assimilation of Thai Chinese has been celebrated in contemporary literature such as "Letters from Thailand" (Thai: จดหมายจากเมืองไทย) by a Thai-chinese author Botan.[37] In the modern Thai language there are many signs of Chinese influence.[38] In the 2000 census, 231,350 identified as speakers of a variant of Chinese (Teochew, Hokkien, Hainanese, Cantonese, or Hakka).[2] The Teochew dialect of Chinese has served as the language of Bangkok's influential Chinese merchants' circles since the foundation of the city in the 18th century. Today, businesses in Yaowarat Road and Charoen Krung Road in Bangkok's Samphanthawong District which constitute the city's "Chinatown" still feature bilingual signs in Chinese and Thai.[39] A number of Chinese words have found their way into the Thai language, especially names of dishes and foodstuff, as well as basic numbers (such as those from "three" to "ten") and terms related to gambling.[2] Chin Haw Chinese speak Southwestern Mandarin.

Some Thai Chinese families encourage their children learn Mandarin Chinese to reap benefits from their ethnic Chinese identity as Mandarin has been increasingly the primary language of business for Overseas Chinese business communities.[40][12][41] But most Thais who study Chinese do so because it boosts their business or career opportunity, rather than because of ethnic identity reason. Although Chinese language schools were closed during the nationalist period before and during the Second World War, the Thai government never tried to suppress the Chinese cultural expressions. Chinese owned businesses have adorned their shops with Chinese language signs, such as in the famous Yaowarat commercial district. Chinese wuxia novels and movies inundated the Thai entertainment market between 1960s and 1980s. However, some Thai families are sending their children to newly established Mandarin language schools in hopes to take advantage of business opportunities in Mainland China.[42][43] The rise of China's global economic prominence has prompted many Thai Chinese business families to see Mandarin as a beneficial asset in partaking in economic links and conducting business between Thailand and Mainland China.[43][44]

Trade and industry

Like much of Southeast Asia, Thai Chinese dominate Thai commerce at every level of society.[45][46][12] Entrepreneurial savvy Chinese have literally taken over Thailand's entire economy.[46][12] Ethnic Chinese wield tremendous economic clout over their indigenous Thai majority counterparts and play a critical role in maintaining the country's economic vitality and prosperity.[46][12][47] In Thailand, the economic power of the Chinese is far greater than that of their proportion in the population in addition to the Chinese being socioeconomically successful for hundreds of years than the indigenous host Thai population.[12][48] With their powerful economic prominence, the Chinese virtually make up the country's entire economically wealthy elite.[12] The development policy spearheaded by the Thai government has provided many business opportunities for the ethnic Chinese. A distinct Sino-Thai business community has emerged as the dominant economic group, controlling virtually all the major business sectors across the country.[49][50] The modern Thai business sector is highly dependent on ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs and investors who control virtually all the country's banks and large conglomerates and their support is enhanced by the large presence of lawmakers and politicians whom are of at least part-Chinese themselves.[51][52][12] The Thai Chinese, a disproportionate wealthy, market-dominant minority not only form a distinct ethnic community, they also form, by and large, an economically advantaged social class: the commercial middle and upper class in contrast to the poorer indigenous Thai majority working and underclass around them.[53][54][55][56][57][58]

British East India Company agent John Crawfurd used detailed company records kept on Prince of Wales's Island (present-day Penang) from 1815 to 1824 to report specifically on the economic aptitude of the 8,595 Chinese there as compared to others. He used the data to estimate the Chinese — about five-sixths of whom were unmarried men in the prime of life — "as equivalent to an ordinary population of above 37,000, and...to a numerical Malay population of more than 80,000!".[59]:p.30 He surmised this and other differences noted as providing, "a very just estimate of the comparative state of civilization among nations, or, which is the same thing, of the respective merits of their different social institutions."[59]:p.34 In 1879, the Chinese controlled all of the steam-powered rice mills, most of which were sold by the British. Most of the leading businessmen in Thailand were of Chinese extraction and accounted for a significant portion of the Thai upper class.[31] In 1890, despite British shipping domination in Bangkok, Chinese conducted 62 percent of the shipping sector, operating for agents for Western shipping firms as well as their own.[31] They also dominated the rubber industry, market gardening, sugar production, and fish exporting sectors. In Bangkok, Thai Chinese dominate the entertainment and media industries, being the pioneers of Thailand's early publishing houses, newspapers, and film studios.[60] Thai Chinese moneylenders wield considerable economic power over the poorer indigenous ethnic Thai peasants as accusations of bribery of government officials, wars between the Chinese secret societies, and use of violent tactics to collect taxes served to foster Thai resentment against the Chinese at a time when the community was expanding rapidly due to immigration. Chinese were also accused of producing poverty for the Thai peasant, charging astronomically high interest rates, when in reality, the Thai banking business was highly competitive.[31] In addition, Chinese millers and rice traders were blamed for an economic recession that gripped Siam for nearly a decade after 1905.[31] Large waves of Han Chinese immigration occurred in the nineteenth and early in the twentieth century, peaking in the 1920s from southern China who were eager to make money and return to their families. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Chinese would lose their control of foreign trade to the European colonial powers and began to act as compradores for Western trading houses. Ethnic Chinese also entered extraction intensive industries such as tin mining, teak-cutting, sawmilling, rice-miling, as well as the transportation sector through building ports and railways.[61]

Mid-20th century Thailand was isolationist with its economy mired in state-owned enterprises. The Chinese served as an important impetus for Thailand's modern industrialization rapidly transforming the Thai domestic economy into an export-oriented trade based economy linked with global capitalism.[62] Over the next several decades, internationalization and capitalist market-oriented policies led to the dramatic emergence of a massive export-oriented, large-scale manufacturing sector, which in turn catapulted Thailand into joining the Tiger Cub Economies.[63] Virtually all the industrial manufacturing and import-export shipping firms establishments including the auto manufacturing behemoth Siam Motors are Chinese controlled.[63][64] In the years between World War I and World War II, Thailand's major exports, rice, tin, rubber, and timber were under Chinese control. Despite their small numbers as compared to the native Thai population, the Chinese have controlled virtually every line of business, ranging from small retail trade to large industries. Comprising merely ten percent of the population, ethnic Chinese dominate over four-fifths of the country's vital rice, tin, rubber, and timber exports, and virtually the country's entire wholesale and retail trade.[65] By 1924, ethnic Chinese controlled three of the nine sawmills in Bangkok. Market gardening, sugar production (The Chinese introduced the sugar industry to Thailand), and fish exporting was dominated by the Chinese.[12][66] Virtually all of the new manufacturing establishments were Chinese controlled. Despite failed Thai affirmative action-based policies in the 1930s to economically empower the impoverished indigenous Thai majority, 70 percent of retailing outlets and 80 to 90 percent of rice mills were controlled by ethnic Chinese.[67] A survey of Thailand's roughly seventy most powerful business groups found that all but three were owned by Thai Chinese.[68] Although Bangkok has its own Chinatown, Chinese influence is much more pervasive and subtle throughout the city. Bangkok's Thai Chinese clan associations are prominent throughout the city as the clans are major property holders and non-profit Chinese operated schools.[69] The Chinese control more than 80 percent of public companies listed on the Thai stock exchange.[70] Kukrit Pramoj, the aristocratic former prime minister and distant relative of the Thai royal family, once said that most Thais had a Chinese relative "hanging somewhere on their family tree."[71][72] By the 1930s, the Thai Chinese minority dominated construction, industrial manufacturing, publishing, shipping, finance, commerce, and every industry in the country, minor, and major.[73] Minor industries included food vending, salt, tobacco, port, and bird's nest concessions.[74] Major industries included shipping, rice milling, tin manufacturing, rubber, teak, and petroleum.[74] Furthermore, all the residential and commercial land in Central Siam were owned by Thai Chinese.[74] 50 ethnic Chinese families controlled the country's entire business sectors equivalent to 81 to 90 percent of the overall market capitalization of the Thai economy with the remainder being either state owned and by a Thai Indian business family.[75][76][77][78][79][80][81][63][82] Highly publicized profiles of wealthy Chinese entrepreneurs attracted great public interest and were used to illustrate the community's strong economic clout.[83] More than 80 percent of the top 40 richest people in Thailand are Thai of full or partial Chinese descent.[84] Thai Chinese entrepreneurs are influential in the real estate, agriculture, banking, and finance, and the wholesale trading industries.[85][86] In the 1990s, among the top ten Thai businesses in terms of sales, nine of them were Chinese-owned with only Siam Cement not being a Chinese-owned firm.[12][87] Of the five billionaires in Thailand in the late-20th century, all were all ethnic Chinese or of partial Chinese descent.[88][89][90] On 17 March 2012, Chaleo Yoovidhya, of humble Chinese origin, passed away while listed on Forbes list of billionaires as 205th in the world and 3rd in the nation, with an estimated net worth of US$5 billion.[91]

From an economic standpoint, Thai Chinese are seen as a fraction of the wealth they have created and added to the host country's economy, and representing what the Chinese have spent on themselves and their families.[92] In the late 1950s, ethnic Chinese comprised 70 percent of Bangkok's business owners and senior business managers and 90 percent of the shares in Thai corporations are said to be held by Thais of Chinese extraction.[7][93][94] 90 percent of Thailand's industrial and commercial capital are also held by ethnic Chinese.[95] 90 percent of all investments in the industry and commercial sector and at least 50 percent of all investments in the banking and finance sectors is controlled by ethnic Chinese.[96][97][98][99] Economic advantages would also persist as Thai Chinese controlled 80 to 90 percent of the rice mills, the largest enterprises in the nation.[92] Thailand’s lack of an indigenous Thai commercial culture in the private sector is dominated entirely by Thai Chinese themselves.[100][101] Of the 25 leading entrepreneurs in the Thai business sector, 23 are ethnic Chinese or of partial Chinese descent.[102] Thai Chinese also comprise 96 percent of Thailand's 70 most powerful business groups with the remainder being the Thai Military Bank, the Crown Property Bureau, and a Thai-Indian business group.[103][63][104][105][106] Family firms are extremely common in the Thai business sector as they are passed down from one generation to the next.[107] 90 percent of Thailand's manufacturing sector and 50 percent of Thailand's service sector is controlled by ethnic Chinese.[108] According to a Financial Statistics of the 500 Largest Public Companies in Asia Controlled by Overseas Chinese in 1994 chart released by Singaporean Geographer Dr. Henry Yeung of the National University of Singapore, 39 companies were concentrated in Thailand with a market capitalization of US$35 billion and total assets of US$94 billion.[107] In Thailand, ethnic Chinese control the nations four largest private banks (Bangkok Bank, Thai Farmers Bank, Bank of Ahudya, and Bangkok Commercial Bank), of which Bangkok Bank is the largest and most profitable private bank in addition to the Thai royal household being dependent on Chinese private equity capital and business expertise from these banks to fund and create more modern businesses.[109][110][111][112][113][114][115] Thai Chinese also dominate the Thai telecommunications sector with well-known names such as the Shinawatra telecommunications group, Telcoms Asia, Jasmine, Ucom, and Samar.[116] Thai Chinese businesses are part of the larger bamboo network, a network of Overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family, ethnic, language, and cultural ties.[117] Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, structural reforms imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Indonesia and Thailand led to the loss of many monopolistic positions long held by the ethnic Chinese business elite.[118] Despite the financial and economic crisis, Thai Chinese are estimated to own 65 percent of the total banking assets, 60 percent of the national trade, 90 percent of all local investments in the commercial sector, 90 percent of all local investments in the manufacturing sector, and 50 percent of all local investments in the banking and financial services sector.[119][120][121]

With the rise of China as a global economic power, Thai-Chinese businesses are now the largest investors in Mainland China among all overseas Chinese communities worldwide.[122][123] The influx of Thai Chinese capital into Mainland China has led to a resurgence of Chinese cultural pride among the Thai Chinese community while concurrently pursuing new business opportunities while bringing their influx of foreign capital to create new jobs and economic niches on the Mainland. Many Thai Chinese have sent their children to newly established Chinese language schools, visiting China in record numbers, investing in China, and assuming Chinese surnames.[43] The Charoen Pokphand (CP Group), a prominent Thai conglomerate claiming $9 billion in assets with US$25 billion in annual sales founded by the Thai-Chinese Chearavanont family is one of the most powerful conglomerate companies investing in Mainland China today.[124] It is currently the single largest foreign investor in China with over $1 billion USD invested with hundreds of businesses from agricultural food products, aquaculture, retail, leisure, industrial manufacturing and employing more than 150,000 people in China.[12][125][126][123][124] It is known in China under well-known household names such as the "Chia Tai Group" and "Zheng Da Ji Tuan". CP Group also owns and operates Tesco Lotus, one of the largest foreign hypermarket operators with 74 stores and seven distribution centers throughout 30 cities across China. One of CP Group's flagship businesses in China is a US$400 million Super Brand Mall, the largest mall in Shanghai's exclusive Pudong business district. Reignwood Pine Valley,[127] CP also controls Telecoms Asia, a joint venture with British Telecom since making its foray in the Thai telecommunications industry.[126] China's most exclusive golf and country clubs, were established and owned by a Thai-Chinese business tycoon, Chanchai Rouyrungruen (operator of Red Bull drink business in China). It is cited as the most popular golf course in Asia. In 2008, Chanchai became the first owner of a business jet in Mainland China.[128] Anand's Saha-Union, Thailand's leading industrial group, have so far invested over US$1.5 billion in China, and is operating more than 11 power plants in three of China's provinces. With over other 30 businesses in China, the company employs approximately 7,000 Chinese workers.[123] Central Group, Thailand's largest operator of shopping centers (and owner of Italy's leading department store, La Rinascente) with US$3.5 billion in annual sales founded by a Thai-Chinese Chirathivat family, have recently opened three new large scale department stores in China.[123]

As ethnic Chinese economic might grew, the indigenous Thai hill tribes and aborigines were gradually driven out into poorer land on the hills, on the rural outskirts of major Thai cities or into the mountains. The increased economic clout wielded by Thai Chinese has triggered distrust, resentment and Anti-Chinese sentiment among the poorer indigenous Thai majority, many whom engage in rural agrarian rice peasantry in a stark socioeconomic contrast to their modern, wealthier, and cosmopolitan middle class Chinese counterparts, who mainly engage in business, the skilled trades, or white collar professional occupations.[53] During the early 20th-century, the Thai nationalist King Vajiravudh, also known as Rama VI wrote in his pamphlet The Jews of the East regarding his view of the Thai Chinese. Rama VI commented that the Thai Chinese were a "problem" for Thailand and compared the Thai Chinese to the Jews as a group of outsider aliens who are loyal to their own ethnic group than that of their own host country.[129] He conjuring up a scapegoating image of successful Chinese businessmen gaining their success at the expense of indigenous Thais resulting many Thai politicians to have tempted to blame Thai Chinese businessmen for Thailand's economic difficulties.[130] King Vajiravudh's pamphlet was immensely influential among elite Thais and quickly spread to ordinary Thais, who were then filled with suspicion and hostility towards the Chinese minority.[129] The wealth disparity and abject poverty among the native ethnic Thai majority has resulted hostility blaming their extreme socioeconomic ills on the Chinese, especially Chinese moneylenders as "bloodsucking" exploitative debilitating shylocks. Beginning in the late 1930s and recommencing in the 1950s, the Thai government majority have dealt with this wealth disparity by pursuing a systematic and ruthless campaign of forced assimilation achieved through property confiscation, forced expropriation, coercive social policies, and draconian policies of anti-Chinese cultural suppression essentially destroying any trace of ethnic Han Chinese consciousness and identity.[131][132] Thai Chinese became targets of state discrimination that gave affirmative action privileges to the indigenous Thai majority peoples first while imposing reverse discrimination against the Chinese minority to gain a supposed equal economic footing.[133][67][134]

Religion

First-generation Chinese immigrants were followers of Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism. Theravada Buddhism has since become the religion of many ethnic Chinese in Thailand, especially among assimilated Chinese. Very often, many Chinese in Thailand combine practices of Chinese folk religion with Theravada Buddhism.[135] Major Chinese festivals such as Chinese New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival and Qingming are widely celebrated, especially in Bangkok, Phuket, and other parts of Thailand where there are large Chinese populations.[136]

The Chinese in Phuket are noted for their nine-day vegetarian festival between September and October. During the festive season, devotees will abstain from meat and mortification of the flesh by Chinese mediums are also commonly seen, and the rites and rituals seen are devoted to the veneration of Tua Pek Kong. Such idiosyncratic traditions were developed during the 19th century in Phuket by the local Chinese with influences from Thai culture.[137]

In the north, there are some Chinese people who practice Islam. They belong to a group of Chinese people, known as Chin Ho. Most of the Chinese Muslims are descended from Hui people who live in Yunnan, China. There are currently seven Chinese mosques in Chiang Mai,[138] one of them is Baan Haw Mosque, a well known mosque in the north.

Dialect groups

The vast majority of Thai Chinese belong to various southern Chinese dialect groups. Of these, 56 percent are Teochew (also commonly spelled as Teochiu), 16 percent Hakka and 11 percent Hainanese. The Cantonese and Hokkien each constitute seven percent of the Chinese population, and three percent belong to other Chinese dialect groups.[139] A large number of Thai Chinese are the descendants of intermarriages between Chinese immigrants and Thais, while there are others who are of predominantly or solely of Chinese descent. People who are of mainly Chinese descent are descendants of immigrants who relocated to Thailand as well as other parts of Nanyang (the Chinese term for Southeast Asia used at the time) in the early to mid-20th century due to famine and civil war in the southern Chinese provinces of Hainan (Hainanese), Guangdong (Teochew, Cantonese and Hakka groups) and Fujian (Hokkien, Henghua, Hockchew and Hakka groups).

Teochew

The Teochews mainly settled near the Chao Phraya River in Bangkok. Many of them worked in government, while others were involved in trade. During the reign of King Taksin, some influential Teochew traders were granted certain privileges. These prominent traders were called "royal Chinese" (Jin-luang or จีนหลวง in Thai).

Hokkien, Hokchew and Peranakan

In the southern Thai provinces, notably the Chinese community in Phuket Province, the assimilated group is known as Peranakans or Phuket Baba. These people share a similar culture and identity with the Peranakan Chinese in neighboring Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia.

The Hokchew is minor community in Phuket.[140][141][142] Ethnic Chinese in the Malay-dominated provinces in the south used Malay, rather than Thai as their lingua franca, and occasionally intermarry with the local Malays.[143]:14-15

Hakka

Hakkas are mainly concentrated in Chiang Mai, Phuket, and central western provinces. The Hakka own many private banks in Thailand, notably Kasikorn Bank and Kiatnakin Bank.

Linguistic concentrations

- Teochew

- Hokkien

- Cantonese

- Hakka

- Hainanese

- Hokchew

Surnames

Almost all Sino-Thais, especially those who came to Thailand before the 1920s, possess a Thai surname, as was required by King Rama VI in order for them to become Thai citizens. The few who retain native Chinese surnames are either recent immigrants or resident aliens.

Sino-Thai surnames are often distinct from those of the general population, with generally longer names mimicking those of high officials and upper-class Thais[144] and with elements of these longer names retaining their original Chinese surname in translation or transliteration. For example, former Prime Minister Banharn Silpa-Archa's unusual Archa element is a translation into Thai of his family's former name Ma (trad. 馬, simp. 马, lit. "horse"). Similarly, the Lim in Sondhi Limthongkul's name is the Hainanese pronunciation of the name Lin (林). Or it may have been done for them. For an example, see the background of the Vejjajiva Palace name.[145] Note that the latter-day Royal Thai General System of Transcription would transcribe it as "Wetchachiwa" and that the Sanskrit-derived name refers to "medical profession."

For immigrants who came between the 1920s and 1950s, it was common to simply prefix Sae- (from Chinese: 姓, "surname") to a transliteration of their name to form the new surname; Wanlop Saechio's last name thus derived from the Chinese 周 and Chanin Sae-ear's last name mean 杨. Sae is also used by Hmong people in Thailand.

Many Thai Chinese people who immigrated after the 1950s use their Chinese surname, without Sae-.

Prime Ministers of (full or partial) Chinese origin

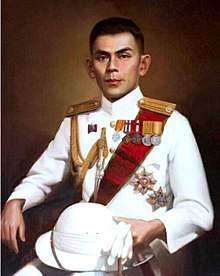

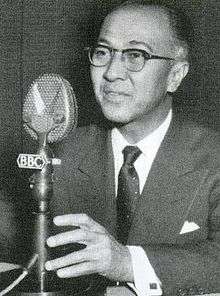

Kon Hutasingha, the 1st Prime Minister of Thailand.

Kon Hutasingha, the 1st Prime Minister of Thailand.

.jpg)

See also

References

- ↑ Barbara A. West (2009), Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, Facts on File, p. 794, ISBN 1438119135

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Theraphan Luangthongkum (2007). "The Position of Non-Thai Languages in Thailand". Language, Nation and Development in Southeast Asia. ISEAS Publishing: 191

- ↑ Chris Baker, Pasuk Phongpaichit. A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-521-81615-7.

- ↑ Time of uncertainty lies ahead for Bangkok’s ethnic Chinese

- ↑ Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia - Annabelle R. Gambe - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 2000-09-02. ISBN 9780312234966. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ A. B. Susanto; Patricia Susa (2013). The Dragon Network: Inside Stories of the Most Successful Chinese Family. Wiley. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- 1 2 Choosing Coalition Partners: The Politics of Central Bank Independence in ... - Young Hark Byun, The University of Texas at Austin. Government - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 2006. ISBN 9780549392392. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Amy Chua, "World on Fire", 2003, Doubleday, pg. 3 & 43.

- ↑ Vatikiotis, Michael (February 12, 1998). Entrerepeeneurs (PDF). Bangkok: Far Eastern Economic Review.

- ↑ "High technology and globalization challenges facing overseas Chinese entrepreneurs | SAM Advanced Management Journal". Find Articles. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 179. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era: Towards Hybrid Capitalism - Henry Wai-Chung Yeung - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 2003-11-13. ISBN 9781134390502. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia - Marshall Cavendish Corporation, Not Available (NA) - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 2007-09-01. ISBN 9780761476313. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Globalization And Social Stress - Grzegorz W. Kołodko - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 2005. ISBN 9781594541940. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Marshall, Tyler (17 June 2006). "Southeast Asia's new best friend". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 58.

- ↑ "Chinese Diaspora". Academy for Cultural Diplomacy.

- ↑ "CHINESE IN THAILAND". Facts and Details.

- ↑ Peleggi, Maurizio (2007). "Thailand: The Worldly Kingdom". Reaktion Books: 46

- ↑ Paul Richard Kuehn, Who Are The Thai-Chinese And What Is Their Contribution to Thailand?

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Skinners, G. William (1957). "Chinese Assimilation and Thai Politics". The Journal of Asian Studies. 16 (2). p. 237-250.

- ↑ Skinners 1957, p. 237.

- ↑ Skinners 1957, p. 240-41.

- ↑ "Letters from Thailand: A Novel".

- ↑ "Sondhi Limthongkul". Political Prisoners in Thailand.

- ↑ Bertil Lintner. Blood Brothers: The Criminal Underworld of Asia. Macmillan Publishers. p. 234. ISBN 1-4039-6154-9.

- ↑ Martin Stuart-Fox. A Short History of China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence. Allen & Unwin. p. 126. ISBN 1-86448-954-5.

- ↑ Smith Nieminen Win (2005). Historical Dictionary of Thailand (2nd ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 231. ISBN 0-8108-5396-5.

- ↑ Rosalind C. Morris (2000). In the Place of Origins: Modernity and Its Mediums in Northern Thailand. Duke University Press. p. 334. ISBN 0-8223-2517-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sowell, Thomas (1997). Migrations And Cultures: A World View. Basic Books. pp. 182–184. ISBN 978-0-465-04589-1.

- 1 2 Wongsurawat, Wasana (November 2008). "Contending for a Claim on Civilization: The Sino-Siamese Struggle to Control Overseas Chinese Education in Siam". Journal of Chinese Overseas. 4 (2). pp. 161–182.

- ↑ Michael Leifer (1996). Dictionary of the Modern Politics of South-East Asia. Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 0-415-13821-3.

- ↑ "Bilateral Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People's Republic of China. 2003-10-23. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

On July 1, 1975, China and Thailand established Diplomatic relations.

- ↑ Chris Dixon (1999). The Thai Economy: Uneven Development and internationalisation. Routledge. p. 267. ISBN 0-415-02442-0.

- ↑ Paul J. Christopher (2006). 50 Plus One Greatest Cities in the World You Should Visit. Encouragement Press, LLC. p. 25. ISBN 1-933766-01-8.

- ↑ https://www.amazon.com/Letters-Thailand-Novel-Botan/dp/9747551675/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1538353071&sr=8-1&keywords=letter+from+thailand. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Knodel, John; Hermalin, Albert I. (2002). "The Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Cultural Context of the Four Study Countries". The Well-Being of the Elderly in Asia: A Four-Country Comparative Study. University of Michigan Press: 38–39

- ↑ Durk Gorter (2006). Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism. Multilingual Matters. p. 43. ISBN 1-85359-916-6.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 59.

- ↑ Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0521639316.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 59.

- 1 2 3 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 59.

- ↑ Snitwongse, Kusuma; Thompson, Willard Scott (2005). Ethnic Conflicts in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (published October 30, 2005). p. 154. ISBN 978-9812303370.

- 1 2 3 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0521639316.

- ↑ Chirot, Daniel; Reid, Anthony (1997). Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. University of Washington Press (published July 1, 1997). p. 277. ISBN 978-0295976136.

- ↑ Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. p. 193. ISBN 978-1567203028.

- ↑ Yu, Bin (1996). Dynamics and Dilemma: Mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong in a Changing World. Edited by Yu Bin and Chung Tsungting. Nova Science. p. 72. ISBN 978-1560723035.

- ↑ Kołodko, Grzegorz (2005). Globalization and Social Stress. Nova Science Pub (published April 30, 2005). p. 171. ISBN 978-1594541940.

- ↑ Redding, Gordon (1990). The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism. De Gruyter. p. 32. ISBN 978-3110137941.

- 1 2 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. pp. 179–183. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Kołodko, Grzegorz (2005). Globalization and Social Stress. Nova Science Pub (published April 30, 2005). p. 171. ISBN 978-1594541940.

- ↑ White, Lynn (2009). Political Booms: Local Money And Power In Taiwan, East China, Thailand, And The Philippines (Series on Contemporary China). WSPC (published June 10, 2009). p. 26. ISBN 978-9812836823.

- ↑ Cornwell, Grant Hermans; Stoddard, Eve Walsh (2000). Global Multiculturalism: Comparative Perspectives on Ethnicity, Race, and Nation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (published December 26, 2000). p. 67. ISBN 978-0742508828.

- ↑ Wongsurawat, Wasana (May 2, 2016). "Beyond Jews of the Orient: A New Interpretation of the Problematic Relationship between the Thai State and Its Ethnic Chinese Community". Cultural Studies. Project MUSE. 2. Duke University Press. 24: 555–582.

- ↑ Chirot, Daniel; Reid, Anthony (1997). Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. University of Washington Press (published July 1, 1997). p. 261. ISBN 978-0295976136.

- 1 2 Crawfurd, John (21 August 2006) [First published 1830]. "Chapter I". Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. p. 30. OCLC 03452414. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

The Chinese amount to 8595, and are landowtiers, field-labourers, mechanics of almost every description, shopkeepers, and general merchants. They are all from the two provinces of Canton and Fo-kien, and threefourths of them from the latter. About five-sixths of the whole number are unmarried men, in the prime of life : so that, in fact, the Chinese population, in point of effective labour, may be estimated as equivalent to an ordinary population of above 37,000, and, as will afterwards be shown, to a numerical Malay population of more than 80,000!

- ↑ Kołodko, Grzegorz (2005). Globalization and Social Stress. Nova Science Pub (published April 30, 2005). p. 171. ISBN 978-1594541940.

- ↑ Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0521639316.

- ↑ Chirot, Daniel; Reid, Anthony (1997). Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. University of Washington Press (published July 1, 1997). p. 261. ISBN 978-0295976136.

- 1 2 3 4 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Kołodko, Grzegorz (2005). Globalization and Social Stress. Nova Science Pub (published April 30, 2005). p. 171. ISBN 978-1594541940.

- ↑ Viraphol, Sarasin (1972). The Nanyang Chinese. Institute of Asian Studies - Chulalongkorn University Press. p. 10.

- ↑ Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0521639316.

- 1 2 Farron, Steven (October 2002). "Prejudice is free but discrimination has costs". The Free Market Foundation.

- ↑ Chua, Amy. "World on Fire" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-25.

- ↑ Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. p. 193. ISBN 978-1567203028.

- ↑ Joint Economic Committee Congress of the United States (1997). China's Economic Future: Challenges to U.S.Policy (Studies on Contemporary China). Routledge. p. 425. ISBN 978-0765601278.

- ↑ Long, Simon (April 1998). "The Overseas Chinese" (PDF). Prospect Magazine. The Economist (29). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Welch, Ivan. Southeast Asia — Indo or China (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Foreign Military Studies Office. p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-07.

- ↑ Kołodko, Grzegorz (2005). Globalization and Social Stress. Nova Science Pub (published April 30, 2005). p. 171. ISBN 978-1594541940.

- 1 2 3 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 182. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Nations, United (2004). Current Issues On Industry Trade And Investment. United Nations Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-9211203592.

- ↑ Tipton, Frank B. (2008). Asian Firms: History, Institutions and Management. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-1847205148.

- ↑ Gambe, Annabelle (2000). "Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia". Palgrave Macmillan. p. 10. ISBN 978-0312234966. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ Buzan, Barry; Foot, Rosemary (2004). Does China Matter?: A Reassessment: Essays in Memory of Gerald Segal. Routledge (published May 10, 2004). p. 82. ISBN 978-0415304122.

- ↑ Wong, John (2014). Political Economy Of Deng's Nanxun, The: Breakthrough In China's Reform And Development. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 214. ISBN 9789814578387.

- ↑ Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. p. 152. ISBN 978-1567203028.

- ↑ Kołodko, Grzegorz (2005). Globalization and Social Stress. Nova Science Pub (published April 30, 2005). p. 171. ISBN 978-1594541940.

- ↑ Yeung, Henry Wai-Chung (2005). Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era: Towards a Hybrid Capitalism. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415309899.

- ↑ "Malaysian Chinese Business: Who Survived the Crisis?". Kyotoreview.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp. Archived from the original on 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ - Forbes Thai 40 Richest

- ↑ Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. p. 193. ISBN 978-1567203028.

- ↑ Yeung, Henry Dr. "Economic Globalization, Crisis and the Emergence of Chinese Business Communities in Southeast Asia" (PDF). National University of Singapore.

- ↑ Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0521639316.

- ↑ Sowell, Thomas (2006). Black Rednecks & White Liberals: Hope, Mercy, Justice and Autonomy in the American Health Care System. Encounter Books. p. 84. ISBN 978-1594031434.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 22.

- ↑ Migrations And Cultures: A World View - Thomas Sowell - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 1996. ISBN 9780465045884. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ "Chaleo Yoovidhya". Forbes. Forbes. March 2012. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

Net Worth $5 B As of March 2012 #205 Forbes Billionaires, #3 in Thailand

- 1 2 Migrations And Cultures: A World View - Thomas Sowell - Google Books

- ↑ "Sidewinder: Chinese Intelligence Services and Triads Financial Links in Canada". Primetimecrime.com. 1997-06-24. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 1999-01-01. ISBN 9781567203028. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Yu, Bin (1996). Dynamics and Dilemma: Mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong in a Changing World. Edited by Yu Bin and Chung Tsungting. Nova Science. p. 73. ISBN 978-1560723035.

- ↑ Ju, Yanan; Chu, Yen-An (1996). Understanding China: Center Stage of the Fourth Power. State University of New York Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0791431221.

- ↑ Yeung, Henry Wai-Chung (2005). Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era: Towards a Hybrid Capitalism. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415309899.

- ↑ Yu, Bin (1996). Dynamics and Dilemma: Mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong in a Changing World. Edited by Yu Bin and Chung Tsungting. Nova Science. p. 71. ISBN 978-1560723035.

- ↑ Ju, Yanan; Chu, Yen-An (1996). Understanding China: Center Stage of the Fourth Power. State University of New York Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0791431221.

- ↑ Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. p. 193. ISBN 978-1567203028.

- ↑ Tipton, Frank B. (2008). Asian Firms: History, Institutions and Management. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-1847205148.

- ↑ Modern Diasporas in International Politics - Gabriel Sheffer - Google Books

- ↑ Richter, Frank-Jurgen (2002). Redesigning Asian Business: In the Aftermath of Crisis. Quorum Books. p. 85. ISBN 978-1567205251.

- ↑ The United States-PRC-ASEAN Triangle: A Transaction Analysis of the 'China ... - Nathan R. Deames, University of South Carolina - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 2007. ISBN 9780549210085. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Myers, Peter (2 July 2005). "The Jewish Century, by Yuri Slezkine". Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ The Jewish Century - Yuri Slezkine - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 2011-06-27. ISBN 1400828554. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- 1 2 Yeung, Henry; Tse Min Soh (August 25, 2000). "Corporate Governance and the Global Reach of Chinese Family Firms in Singapore" (PDF). Corporate Governance and the Global Reach of Chinese Family Firms in Singapore. Department of Geography, National University of Singapore. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Yeung, Henry Wai-Chung (2005). Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era: Towards a Hybrid Capitalism. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415309899.

- ↑ Sowell, Thomas (2006). Black Rednecks & White Liberals: Hope, Mercy, Justice and Autonomy in the American Health Care System. Encounter Books. p. 84. ISBN 978-1594031434.

- ↑ Yeung, Henry Wai-Chung (2005). Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era: Towards a Hybrid Capitalism. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415309899.

- ↑ Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. p. 193. ISBN 978-1567203028.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 22.

- ↑ Redding, Gordon (1990). The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism. De Gruyter. p. 32. ISBN 978-3110137941.

- ↑ Murray Weidenbaum. "The Bamboo Network: Asia's Family-run Conglomerates". Strategy-business.com. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives - Google Books. Books.google.ca. 1999-01-01. ISBN 9781567203028. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Gomez, Edmund (2012). Chinese business in Malaysia. Routledge. p. 93. ISBN 978-0415517379.

- ↑ Murray L Weidenbaum (1 January 1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia. Martin Kessler Books, Free Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-684-82289-1.

- ↑ Yeung, Henry. "Change and Continuity in SE Asian Ethnic Chinese Business" (PDF). Department of Geography, National University of Singapore.

- ↑ Ju, Yanan; Chu, Yen-An (1996). Understanding China: Center Stage of the Fourth Power. State University of New York Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0791431221.

- ↑ Goossen, Richard. "The spirit of the overseas Chinese entrepreneur, by" (PDF).

- ↑ Chen, Min (1995). Asian Management Systems: Chinese, Japanese and Korean Styles of Business. Cengage Learning. p. 65. ISBN 978-1861529411.

- ↑ Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 184. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- 1 2 3 4 - CP Group Archived 2011-06-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0521639316.

- 1 2 Gomez, Edmund (2012). Chinese business in Malaysia. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0415517379.

- ↑ "Reignwood Pine Valley". advertisement. Reignwood Pine Valley. April 18, 2012. Archived from the original (enter website) on 2010-02-20. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

Reignwood Pine Valley, one of China's top rated championship golf courses and private member clubs developed by the Reignwood Group, is situated in the Changping District of Beijing and is just a 40-minute drive from the capital.

- ↑ - Reignwood Archived 2011-08-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. pp. 181–183. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Cornwell, Grant Hermans; Stoddard, Eve Walsh (2000). Global Multiculturalism: Comparative Perspectives on Ethnicity, Race, and Nation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (published December 26, 2000). p. 67. ISBN 978-0742508828.

- ↑ Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 183. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 58.

- ↑ Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ↑ Chua, Amy L. (January 1, 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108: 57–58.

- ↑ Martin E. Marty, R. Scott Appleby, John H. Garvey, Timur Kuran. Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Polities, Economies, and Militance. University Of Chicago Press. p. 390. ISBN 0-226-50884-6.

- ↑ Tong Chee Kiong; Chan Kwok Bun (2001). Rethinking Assimilation and Ethnicity: The Chinese of Thailand. Alternate Identities: The Chinese of Contemporary Thailand. pp. 30–34.

- ↑ Jean Elizabeth DeBernardi (2006). The Way That Lives in the Heart: Chinese Popular Religion and Spirits Mediums in Penang, Malaysia. Stanford University Press. pp. 25–30. ISBN 0-8047-5292-3.

- ↑ "»ÃÐÇѵԡÒÃ;¾¢Í§¨Õ¹ÁØÊÅÔÁ". Oknation.net. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ William Allen Smalley (1994). Linguistic Diversity and National Unity: Language. University of Chicago Press. pp. 212–3. ISBN 0-226-76288-2.

- ↑ Celebrating Chinese New Year I

- ↑ Archived 2008-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ บาบ๋า-เพอรานากัน ประจำปีครั้งที่ 19 ณ จังหวัดภูเก็ต

- ↑ Andrew D.W. Forbes (1988). The Muslims of Thailand. Soma Prakasan. ISBN 974-9553-75-6.

- ↑ Mirin MacCarthy. "Successfully Yours: Thanet Supornsaharungsi." Pattaya Mail. [Undated] 1998.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 26, 2005. Retrieved 2005-04-26.

- ↑ Roger Kershaw (2001). "Monarchy in South-East Asia: The Faces of Tradition in Transition". Routledge: 138

- ↑ Lim Hua Sing (6 July 2001). "Chinese adopt patriotism of their new homes". Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 13 November 2012

- 1 2 3 Duncan McCargo; Ukrist Pathmanand (2005). "The Thaksinization Of Thailand". NIAS Press: 4

- 1 2 3 Surasak Tumcharoen (29 November 2009). "A very distinguished province: Chanthaburi has had some illustrious citizens". Bangkok Post

Further reading

- Disaphol Chansiri (2008). "The Chinese Émigrés of Thailand in the Twentieth Century". Cambria Press

- Supang Chantavanich (1997). Leo Suryadinata, ed. From Siamese-Chinese to Chinese-Thai: Political Conditions and Identity Shifts among the Chinese in Thailand. Ethnic Chinese as Southeast Asians. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 232–259.

- G. William Skinner (2008). "Chinese Society in Thailand: An Analytical History". Lightning Source

- Tong Chee Kiong; Chan Kwok Bun (eds.) (2001). Alternate Identities: The Chinese of Contemporary Thailand. Times Academic Press. ISBN 981-210-142-X

- Skinner, G. William. Chinese Society in Thailand, an Analytic History. Ithaca (Cornell University Press), 1957.

- Skinner, G. William. Leadership and Power in the Chinese Community in Thailand. Ithaca (Cornell University Press), 1958.

- Sng, Jeffery; Bisalputra, Pimpraphai (2015). A History of the Thai-Chinese. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 978-981-4385-77-0.