Chaldean Catholics

|

Chaldean Catholics from Mardin, 19th century. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 640,828 (2016)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Middle East | 300,000+ |

| 241,471 (2016)[1] | |

| 48,594 (2016)[1] | |

| 10,000 (2016)[1] | |

| 3,390 (2016)[1] | |

| Diaspora | 300,000+ |

| 245,000 (2016)[1] | |

| 35,000 (2016)[1] | |

| 31,372 (2016)[1] | |

| Religions | |

| Chaldean Catholic Church | |

| Scriptures | |

| The Bible | |

| Languages | |

|

Neo-Aramaic (Assyrian, Chaldean, Turoyo) | |

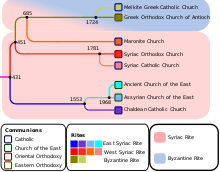

Chaldean Catholics (/kælˈdiːən/), known simply as Chaldeans (Kaldāye; ܟܠܕܝ̈ܐ or ܟܲܠܕܵܝܹܐ), are Assyrian adherents of the Chaldean Catholic Church which originates from the Church of the East.[2][3]

The community formed in the Upper Mesopotamia in the 16th and 17th centuries, originating from groups of "Nestorians" adhering to the Church of the East that split after the schism of 1552 and entered communion with the Holy See (Catholic Church). While indigenous to the region of north Iraq, southeast Turkey and northeast Syria, many Chaldean Catholic Christians have migrated to Western countries including the USA, Canada, Australia, Sweden and Germany. Many of them also live in Lebanon, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Iran, Turkey, and Georgia. The reasons for migration are religious persecution, ethnic persecution, the poor economic conditions during the sanctions against Iraq, and poor security conditions after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Names

Followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church identify and are identified as "Chaldean" (kaldāye, kaldāni, ultimately from ancient "Chaldea"). After the community entered communion with Rome, the Roman Catholic Church began calling them Chaldean Catholics, wanting to differentiate them from the followers of their mother church, the Nestorians (since the 20th century called Assyrians).[4] In the past, the Chaldean name was used for both branches, but never became attached to the Nestorians.[5] The Jacobites (Syriac Orthodox) and Nestorians had up until after World War I called themselves "Syrians" (Suraye/Suroyo), after which the Nestorians gradually adopted Aturaye (ancient Assyrian name in Syriac) while the Jacobites continued calling themselves Suroyo.[6] 19th-century Western travel and missionary writers had popularized the Assyrian name, which was first adopted by a few educated Nestorians (especially immigrants in America) in the late 19th century.[7] In the Interwar period, in some regions, the label "Assyrians" also included Chaldeans, leading to the designation "Catholic Assyrians". [8] However, the Assyrian name did not win approval in the majority of the Chaldean population.[8] In recent times, the term "Chaldo-Assyrian" has gained popularity; it presents Chaldeans and Nestorians as one ethnic group.[8]

In Iraq, the Chaldeans grouped together with Nestorians are officially known as "Chaldo-Assyrian" (as per Law of 2003). Iraqi Kurdish organizations often refer to Syriac Christians as Kurdish Christians, while "Chaldo-Assyrian" is the preferred name of the Assyrian Democratic Movement.[9]

Population

There are 640,828 adherents of the Chaldean Church worldwide according to the Annuario Pontificio.[1]

Iraq

Chaldeans are mentioned as a distinct group in Article 125 of the Iraqi constitution.[10] In northern Iraq, the community inhabits Alqosh (ܐܠܩܘܫ), Ankawa (ܥܢܟܒ݂ܐ), Araden (ܐܪܕܢ), Baqofah (ܒܝܬ ܩܘܦ̮ܐ), Batnaya (ܒܛܢܝܐ), Karamles (ܟܪܡܠܫ), Mangesh (ܡܢܓܫ), Shaqlawa (ܫܩܠܒ݂ܐ), Tel Isqof (ܬܠܐ ܙܩܝܦ̮ܐ), Tel Keppe (ܬܠ ܟܦܐ) and Zakho (ܙܟ݂ܘ).

Syria, Turkey and Iran

In Syria, adherents number 10,000; 48,594 in Turkey; 3,390 in Iran.[1]

Diaspora

In Southeast Michigan there is a Chaldean community numbering 34–113,000 people.[11] This is the largest Chaldean diaspora community outside Iraq.[11] Members are Arabic- or Aramaic-speaking.[11]

A small number of Chaldean Catholic families live in Israel and the Palestinian territories. Occasionally the Chaldean Patriarchate has tried to administer them through the Chaldean street residence of a currently vacant Chaldean Patriarchal Exarch in Jerusalem.

History and origin

The Chaldean community originates from groups of adherents of the Church of the East that entered into communion with the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th and 17th centuries.[12][13] The community emerged after the schism of 1552.[14] These "Nestorian" Uniates received the name "Chaldeans" from the Roman Curia, which had given the ancient name Chaldaei to them.[15]

The term Chaldean in reference to followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church was historically mainly a denominational term which arose in the late 17th century and became fully established in the 19th century. It did not refer to an ethnic connection with ancient south Babylonian Chaldea and its inhabitants, which emerged during the 9th century BC after Chaldean tribes migrated from the Levant region of Urfa in North Mesopotamia to southeast Mesopotamia, and disappeared from history during the 6th century BC.[16]

Chaldean Catholics are regarded ethnically and historically as a part of the Assyrian continuity.[17][18][19][20][21][22] The modern Chaldean Catholics originated from ancient Assyrian communities living in and indigenous to the north of Iraq/Mesopotamia which was known as Assyria from the 25th century BC until the 7th century AD.[23][17][24] Chaldean Catholics largely bear the same family and personal names, share the same genetic profile, hail from the same villages, towns and cities in northern Iraq, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria and northwest Iran, as fellow Assyrians of other religious denominations.[16] The Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Assyrian Neo-Aramaic and Surayt/Turoyo languages do not run parallel to the often associated religious denominations (Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox Church).

20th century

According to a 1950 CIA report on Iraq, Chaldeans numbered 98,000 and were the largest Christian minority.[25]

A 1950 CIA report on Iraq estimated 98,000 Chaldeans, 30,000 Nestorians (Assyrians), 25,000 Syriac Catholics and 12,000 Jacobites.

21st century

According to estimates by the Catholic Church, in Chaldean dioceses in Iraq there were 150,000 Catholics in the Archdiocese of Baghdad (2015),[26] 30,000 in the Archeparchy of Arbil (2012),[27] 22,300 in the Diocese of Alquoch (2012),[28] 18,800 in the Diocese of Amadiyah and Zaku (2015),[29] 14,100 in the Archeparchy of Mossul (2013),[30] 7,831 in the Archdiocese of Kerkūk (2013),[31] 1,372 in Diocese of Aqrā (2012),[32] 800 in Archeparchy of Bassorah (2015),[33]

Identity

Assyrian nationalism among Chaldeans

Many Chaldean Catholics identify as Assyrians or Chaldo-Assyrians. Raphael Bidawid, the then patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church commented on the Assyrian name dispute in 2003:

- "I personally think that these different names serve to add confusion. The original name of our Church was the ‘Church of the East’ … When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic in the 17th Century, the name given was ‘Chaldean’ based on the Magi kings who were believed by some to have come from what once had been the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name ‘Chaldean’ does not represent an ethnicity, just a church… We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion… I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian."[34]

In an interview with the Assyrian Star in the September–October 1974 issue, he was quoted as saying:

- "Before I became a priest I was an Assyrian, before I became a bishop I was an Assyrian, I am an Assyrian today, tomorrow, forever, and I am proud of it."[17]

Chaldean nationalism

Some Chaldean Catholics espouse a Chaldean ethnic identity and regard Chaldeans as a nation of its own. Some claim descent from the ancient Chaldeans/Chaldees, who resided in the far south east of Mesopotamia, however, the scholary consensus remains that modern Chaldean Catholics constitute part of the Assyrian continuity rather than being descendants of the ancient Chaldeans.[23][35][24] The first political movement of Chaldean Catholics was founded in 1972 in Iraq and named the Chaldean Patriot Movement, after the Baathist regime in Iraq killed many Chaldean Catholics in the Soria village in the Dohuk province, but then this movement dissolved after persecution by the Baath regime.[36] Official statistics in Iraq referred to all Syriac Christians, including Chaldean Catholics, as Christian Arabs. In 1972, the cultural rights of Syriac-speaking Christians in Iraq were recognised by the Iraqi government, but the Baathist regime refused to recognize Assyrians (Syriac Christians) as an ethnic group.[37]

After the fall of the Baath regime in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1991, some Chaldean Catholics began to establish Chaldean nationalist political parties around the Chaldean Catholic identity, in 1999 founded the Chaldean Democratic Party and in 2002 the Chaldean National Congress Party.[38][39] Upon their demands, the Iraqi constitution of 2005 in Article 125 mentions Chaldeans as a distinct group.[10] Several conferences on Chaldean nationalism were held,[40][41] and a flag was designed.[42]

Condition of the Chaldean Catholic Church

The 1896 census of the Chaldean Catholics[43] counted 233 parishes and 177 churches or chapels, mainly in northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The Chaldean Catholic clergy numbered 248 priests; they were assisted by the monks of the Congregation of St. Hormizd, who numbered about one hundred. There were about 52 Assyrian Chaldean schools (not counting those conducted by Latin nuns and missionaries). At Mosul there was a patriarchal seminary, distinct from the Chaldean seminary directed by the Dominicans. The total number of Assyrian Chaldean Christians as by 2010 was 490,371,[1] 78,000 of whom are in the Diocese of Mosul.

The current patriarch considers Baghdad as the principal city of his see. His title of "Patriarch of Babylon" results from the identification of Baghdad with ancient Babylon (however Baghdad is 55 miles north of the ancient city of Babylon and corresponds to northern Babylonia). However, the Chaldean patriarch resides habitually at Mosul in the north, and reserves for himself the direct administration of this diocese and that of Baghdad.

There are five archbishops (resident respectively at Basra, Diyarbakır, Kirkuk, Salmas and Urmia) and seven bishops. Eight patriarchal vicars govern the small Assyrian Chaldean communities dispersed throughout Turkey and Iran. The Chaldean clergy, especially the monks of Rabban Hormizd Monastery, have established some missionary stations in the mountain districts dominated by The Assyrian Church of the East. Three dioceses are in Iran, the others in Turkey.

The liturgical language of the Chaldean Catholic Church is Syriac and the liturgy of the Chaldean Church is written in the Syriac alphabet. The literary revival in the early 20th century was mostly due to the Lazarist Pere Bedjan, an ethnic Assyrian Chaldean Catholic from northwestern Iran. He popularized the ancient chronicles, the lives of Assyrian saints and martyrs, and even works of the ancient Assyrian doctors among Assyrians of all denominations, including Chaldean Catholics, Syriac Orthodox, Assyrian Church of the East and Assyrian Protestants.[44]

Before the Gulf War, Chaldean Catholics numbered approximately 400,000[1] of Iraq's estimated 800,000-1,000,000 Assyrian Christians, with smaller numbers found among the Assyrian Christian communities of northeast Syria, southeast Turkey, northwest Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Georgia and Armenia.[45] Perhaps the best known Iraqi Chaldean Catholic is the former Iraqi deputy prime minister, Tariq Aziz (real name Michael Youhanna).[45]

Hundreds of thousands of Assyrian Christians of all denominations have left Iraq since the ousting of Saddam Hussein in 2003. At least 20,000 of them have fled through Lebanon to seek resettlement in Europe and the US.[46] In March 2008, Chaldean Catholic Archbishop Paulos Faraj Rahho of Mosul was kidnapped, and found dead two weeks later. Pope Benedict XVI condemned his death. Sunni and Shia leaders also expressed their condemnation.[47] As political changes sweep through many Arab nations, the ethnic Assyrian minorities throughout the Middle East have expressed concern about the developments and their future in the region.[48]

Organizations

- Parties

- Chaldean Democratic Union, Chaldean Christian democratic party in Iraq

- Chaldean Syriac Assyrian Popular Council, joint Chaldean-Syriac-Assyrian democratic party in Iraq

- Militia

Notable people

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 CNEWA 2016.

- ↑ George V. Yana (Bebla), "Myth vs. Reality" JAA Studies, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 2000 p. 80

- ↑ "Who are the Chaldean Christians?". BBC News. March 13, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ↑ Joseph 2000, p. 8.

- ↑ Joseph 2000, pp. 4, 8.

- ↑ Joseph 2000, p. 9.

- ↑ Joseph 2000, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Berg 2009, p. 160.

- ↑ Karl R. DeRouen; Paul Bellamy (2008). International Security and the United States: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-275-99254-5.

- 1 2 "Iraqi Constitution" (PDF). Government of Iraq.

- 1 2 3 Robson 2016, p. 267.

- ↑ Berg 2009, pp. 155–.

- ↑ Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- ↑ George V. Yana (Bebla) (2000). "Myth vs. Reality". JAA Studies. XIV (1): 80.

- ↑ Becker, p. 302.

- 1 2 Travis 2010.

- 1 2 3 Mar Raphael J Bidawid. The Assyrian Star. September–October, 1974:5.

- ↑ Rassam, H. (1897), Asshur and the Land of Nimrod London

- ↑ Rev. W.A. Wigram (1929), The Assyrians and Their Neighbours London

- ↑ Efram Yildiz's "The Assyrians" Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 13.1, pp. 22, ref 24

- ↑ “The Eastern Christian Churches” by Ronald Roberson. “In 1552, when the new patriarch was elected, a group of Assyrian bishops refused to accept him and decided to seek union with Rome. They elected the reluctant abbot of a monastery, Yuhannan Sulaqa, as their own patriarch and sent him to Rome to arrange a union with the Catholic Church. In early 1553 Pope Julius III proclaimed him Patriarch Simon VIII “of the Chaldeans” and ordained him a bishop in St. Peter’s Basilica on April 9, 1553

- ↑ Aqaliyat shimal al-‘Araq; bayna al-qanoon wa al-siyasa” (Northern Iraq Minorities; between Law and Politics) by Dr. Jameel Meekha Shi’yooka

- 1 2 Nisan 2002, p. ?.

- 1 2 Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS) 18 (2): 22.

- ↑ "National Intelligence Survey: Iraq: Section 43" (PDF). CIA.

- ↑ "Archdiocese of Baghdad (Chaldean)".

- ↑ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/darbi.html

- ↑ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dalqu.html

- ↑ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/damza.html

- ↑ "Archeparchy of Mossul (Chaldean)".

- ↑ "Archdiocese of Kerkūk (Chaldean)".

- ↑ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/daqra.html

- ↑ "Archeparchy of Bassorah {Basra} (Chaldean)".

- ↑ Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. JAAS. 18 (2): 22.

- ↑ Travis 2010, p. ?.

- ↑ "اخبار - حركة كلدانية تحذر من أزمة مالية خطرة بسبب غسيل الريال الإيراني في العراق". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "دار الكتب والوثائق العراقية » ابحث في الفهارس". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Apps - Access My Library - Gale". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ Hanna, Ghassan. "Chaldean National Congress". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "CHALDEAN WRITERS". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "The Chaldean Renaissance: Basic Outline of a Vision". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Chaldean Flag".

- ↑ Mgr. George 'Abdisho' Khayyath to the Abbé Chabot (Revue de l'Orient Chrétien, I, no. 4)

- ↑ "New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia".

- 1 2 BBC 2008.

- ↑ Martin Chulov (2010) "Christian exodus from Iraq gathers pace"The Guardian, retrieved June 12, 2012

- ↑ "Iraqi archbishop death condemned". BBC News. 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2009-12-31. from BBC News

- ↑ R. Thelen (2008) Daily Star, Lebanon retrieved June 12, 2012

Sources

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon.

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1896). "Éttat religieux des diocèses formant le patriarcat chaldéen de Babylone". Revue de l'Orient chrétien. 1: 433–453.

- Joseph, John (2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: Encounters with Western Christian missions, archaeologists, and colonial power. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-32005-5.

- Lukitz, Liora (2005). Iraq: The Search for National Identity. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-77821-7.

- Laura Robson (18 May 2016). Minorities and the Modern Arab World: New Perspectives. Syracuse University Press. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-0-8156-5355-4.

- Travis, Hannibal (2010) [2007]. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. pp. 237–77, 293–294. ISBN 9781594604362.

- Nisan, M. (2002). Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle for Self Expression. Jefferson: McFarland & Company.

- "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2016. Source: Annuario Pontificio" (PDF). CNEWA. 2016. pp. 3–4.

- Kristian Girling (2017). The Chaldean Catholic Church: Modern History, Ecclesiology and Church-State Relations. Taylor & Francis. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-1-351-70674-2.

Further reading

- Natalie Henrich; Joseph Patrick Henrich (2007). Why Humans Cooperate: A Cultural and Evolutionary Explanation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531423-6.

- Oussani, G., 1901. The modern Chaldeans and Nestorians, and the study of Syriac among them. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 22, pp. 79–96.

- Hanoosh, Y.S., 2008. The politics of minority Chaldeans between Iraq and* America. University of Michigan.

- Mary C. Sengstock (1999). Chaldean Americans: Changing Conceptions of Ethnic Identity. Center for Migration Studies. ISBN 978-1-57703-013-3.

- Mary C. Sengstock (2005). Chaldeans in Michigan. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-742-6.

- Jacob Bacall (2014). Chaldeans in Detroit. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-1255-0.

- Suha Rassam (2005). Christianity in Iraq: Its Origins and Development to the Present Day. Gracewing Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85244-633-1.

- Murre-van den Berg, H., 2009. Chaldeans and Assyrians: The Church of the East in the Ottoman Period. The Christian Heritage of Iraq, pp. 157–161.

- Alichoran, J., 1994. Assyro-Chaldeans in the 20th Century: From Genocide to Diaspora. Journal of the Assyrian Academic Society, 8, pp. 45–79.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chaldean Catholic Church. |

- "Who are the Chaldean Christians?". BBC News. March 13, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- The Chaldean Catholic Church

- Iraq: Chaldean Christians UNHCR

- Chaldean Christians in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- BBC: Who are the Chaldean Christians?

![]()