Syriac Orthodox Church in the Middle East

| Suryoye | |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Middle East | 150,000–450,000 |

| 82,000(mid-1970s)-400,000(2016)[a] | |

| 28,000 (2014) | |

| 50-70,000 (2014) | |

| few thousand (1987) | |

| 200–1,500 | |

| Diaspora | 150,000+ |

| 37–55,000 (2005) | |

| 50,000 (2010) | |

| 50,396 (2015) | |

| Languages | |

| Neo-Aramaic (incl. Turoyo), Arabic, Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Syriac Orthodox | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Assyrians, some Syriac Christian groups (especially Syriac Catholics) | |

|

a- other Assyrian subgroups included within that figure | |

Syriac Orthodox Christians, known simply as Syriacs (Suryoye), are an Assyrian ethno-religious[1] subgroup who follow the West Syrian Rite Syriac Orthodox Church in the Middle East and the diaspora, numbering between 150,000 and 200,000 people in their indigenous area of habitation in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey according to estimations.

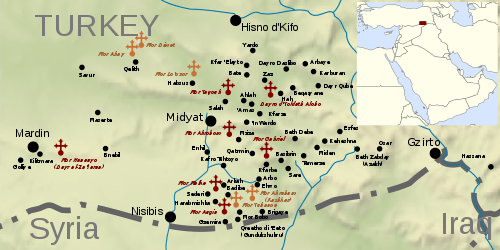

The community formed and developed in the Near East in the Middle Ages. The Syriacs of the Middle East speak Neo-Aramaic (their original and liturgical language) Arabic, and in the case of Syriacs from Turkey, sometimes Turkish. The traditional cultural and religious center of the Syriac Orthodox is Tur Abdin, regarded as their homeland, in southeastern Turkey, from where many people fled the Ottoman government-organized genocide (1914–18) to Syria and Lebanon, and Mosul in northern Iraq. Significant diaspora communities exist in Western Europe and North America as a result of this, and other conflicts since then, as well.

The Syriac Orthodox community is part of the wider community of Middle Eastern Christians who adhere to Syriac Christianity, which comprise various different Oriental Christian groups such as Maronites, Syriac Catholics, and others.

Identity

There is an ongoing debate over the identification of the people. Commonly seen as a part of the Assyrian people,[2] the community tends to identify as "Syrian" (Suryoye), or more recently "Syriac".[2] Today some also identify themselves as either Othuroyo or Oromoyo, which is synonymous with identifying oneself as "Assyrian" or "Aramean".[3] They have also been called "Jacobites", after Bishop Jacob Baradaeus (d. 578) of Edessa, and "Monophysites" (owing to the division of Syriac Church bodies).[4] The identification as "Assyrians" means that they share identity with non-Orthodox Syriacs (such as Nestorians, Syriac Catholics and Chaldean Catholics), while the "Aramean" identity almost solely represents the Syriac Orthodox.[5]

The ethnic identification of Syriac Orthodox as "Assyrians" is contested by the community itself.[6] In the diaspora, the Syriac Orthodox identify with the term Suryoye.[7] In Arabic and Kurdish, they were identified as Suryani, and in Turkish as Süryaniler.[7] In Tur Abdin (Turkey), the community did not consider converts to Protestantism (Prut) and Catholicism (Katholik, Kaldoye) as Suryoye, thus, in Tur Abdin the identification as Syriac only applied to the Syriac Orthodox, who share a collective identity and consciousness.[8]

In the 19th century, the various Syriac denominations did not view themselves as part of one group.[9] The Syriac Orthodox community in the Ottoman Empire was for long not recognized as its own millet (legal entity), but part of the Armenian millet (under the Armenian Patriarch).[10] Then, during the Tanzimat reforms (1839–78), the Syriac Orthodox were granted independent status with the recognition of their own millet in 1873.[11] Late 19th- and early 20th-century Syriac Orthodox intellectuals predominantly used the "Assyrian" identification.[12] Despite this "Assyrian" intellectual trend, the identity of Syriac Orthodoxy in the Ottoman Empire in the 1910s was principally religious and linguistic.[13]

The Syriac Orthodox identity was not only religious, although this was dominant, but also included cultural traditions of the pagan Assyrian and Aramean kingdoms.[14] Syriac Orthodox traditions crystallized into ethnogenesis through their invention of an own tradition, of their stories and customs, the Syriac Orthodox being aware of their core identity already by the 12th century.[14]

History

Middle Ages

The 8th-century hagiography Life of Jacob [Baradaeus] evidents a definite social and religious differention between the Chalcedonians and Miaphysites (Syriac Orthodox).[15] By the time of the longer hagiography on Jacob Baradaeus, he had become the hero of the "Jacobite" Syriac Orthodox Church; the followers eventually wore his name.[16] The longer hagiography shows that the Syriac Orthodox (called "Jacobites" in the work, suryoye yaquboye) self-identified with Jacob's story more than those of other saints.[17] Coptic patriarch Al-Muqaffa (ca. 897), of Miaphysite (Syriac Orthodox) ancestry, speaks of Jacobite origins, on the veneration of Jacob Baradaeus; he explained that the Chalcedonian "Melkites" were labelled as such because the Miaphysite Jacobites never traded their Orthodoxy to win the favour of the king as the Melkites had done (malko is derived from "king, ruler").[18]

It has been assumed that in the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268), the Syriac Orthodox made up the civilian population, their elite consisting of clergy; they did not participate in the military nor administration.[19] It seems that in Antioch itself, after the 11th-century persecutions, the Syriac Orthodox population was almost extinguished.[19] Only one Jacobite church is attested in Antioch in the first half of the 12th century, while a second and third are attested in the second half of the century, perhaps due to refugee influx.[19] Dorothea Weltecke thus concludes that the Syriac Orthodox populace was very low in this period in Antioch and its surroundings.[19] In Adana, on the other hand, an anonymous 1137 report speaks of the entire population consisting of Syriac Orthodox.[19] In the 12th century several Syriac Orthodox patriarchs visited Antioch and some established temporary residences.[20] In the 13th century the Syriac Orthodox hierarchy in Antioch was prepared to accept Latin supervision, however, for the whole Church, this was of little consequence.[21]

The Syriac Orthodox were the most numerous non-Latin sect in Jerusalem and Bethlehem prior to 1187.[22] Before the advent of the Crusades, the Jacobites were probably the majority of the hill country of Jazirah (northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey).[23]

16th century

Moses of Mardin (fl. 1549–d. 1592) was a diplomat of the Syriac Orthodox Church in Rome in the 16th century.[24]

17th century

By the early 1660s, 75% of the 5,000 Syriac Orthodox of Aleppo had converted to Catholicism following the arrival of Friar missionaries.[25] The Catholic missionaries had sought to place a Catholic patriarch among the Jacobites, and consecrated Andrew Akhijan as the patriarch of the newly founded Syriac Catholic Church.[25] The Propaganda Fide and foreign diplomats pushed for Akhijan to be recognized as the Jacobite patriarch, and the Porte then consented, and warned the Syriac Orthodox that they would be considered an enemy if they did not recognize him.[26] Despite the warning and gifts to priests, frequent conflicts and violent arguments continued between the Catholic and Orthodox Syriacs.[26]

19th century

In the 19th century, the various Syriac Christian denominations did not view themselves as part of one ethnic group.[9] During the Tanzimat reforms (1839–78), the Syriac Orthodox were granted independent status by obtaining recognition as their own millet in 1873, separate from Armenians and Greeks.[11]

In the late 19th century, the Syriac Orthodox community of the Middle East, primarily from the cities of Adana and Harput began the process of creating the Syriac diaspora, with the United States being one of their first destinations in the 1890s.[27] Later, in Worcester, the first Syriac Orthodox Church in the United States was built, where it was originally called the Assyrian Apostolic Church of Antioch.[28]

The 1895–96 massacres in Turkey affected the Armenian and Syriac Orthodox communities; an estimated 105,000 Christians were killed.[29] By the end of the 19th century, 200,000 Syriac Orthodox Christians remained in the Middle East, most concentrated around Deir el-Zaferan, the Patriarchal seat.[30]

In 1870, there were 22 Syriac Orthodox settlements in the vicinity of Diyarbakır.[31] In the 1870–71 Diyarbakır salnames, there were 1,434 Orthodox Syriacs in that city.[32] In the 1881/82–93 census, the kaza of Diyarbakır had 4,046 "monophysites" (Syriac Orthodox), while the sanjak of Diyarbakır had 5,909 Syriac Orthodox.[33] The results of these records shows that the Syriac Orthodox were rural, as opposed to the Catholics who were less but more urbanized.[34] The 1894–95 salname of Diyarbakır records 4,096 Syriac Orthodox in the kaza.[34] In the 1897–98 salname the vilayet (province) of Diyarbakır had 20,082 Syriac Orthodox, out of 84,906 non-Muslims.[34]

Rivalry within the Syriac Orthodox Church in Tur Abdin resulted in many conversions to the Syriac Catholic Church (the Uniate branch).[35]

20th century

Genocide (1914–18)

The Ottoman authorities killed and deported Orthodox Syriacs, then looted and appropriated their properties.[36] During 1915–16, the number of Orthodox Syriacs in the Diyarbakır province was reduced by 72%, and in the Mardin province by 58%.[37]

Inter-war period

In 1924, the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Church was transferred to Homs in Syria.[38] This happened after Kemal Atatürk expelled the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch, who took the library of Deir el-Zaferan and settled in Damascus.[30] The Syriac Orthodox villages in Tur Abdin suffered from the 1925–26 Kurdish rebellions; massive flight to Lebanon, northern Iraq and especially Syria ensued.[39]

In early 1920s, the city of Qamishli was built mainly by Syriac Orthodox refugees, escaping the Assyrian genocide.

1945–present

In 1959, the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Church was transferred to Damascus in Syria.[38]

In the mid-1970s, it was estimated that 82,000 Syriac Orthodox lived in Syria.[40]

In 1977, the number of Syriac Orthodox followers in diaspora dioceses were: 9,700 in the Diocese of Middle Europe; 10,750 in the Diocese of Sweden and surrounding countries.[41]

By 1990, there were 4,000 Syriac Orthodox in Tur Abdin.[30]

After the Turkish–PKK ceasefire in 1999, the conditions of Christians in Turkey have improved.[38]

Population

Estimations of the total number of Syriac Orthodox Christians in the Middle East include: 150–200,000 (2002)[42],146,300 (2008)[43] and 500,000(2016). In the diaspora, there are significant communities in Western Europe and North America, most notably in Sweden, Germany and the United States. A Syriac migration wave out of Turkey was prompted by the Turkey-PKK conflict (1970s–90s). Syriac Orthodox refugees from Syria and Iraq have recently increased the number of Syriacs in Turkey and the diaspora as a result of the invasion of the Nineveh Plains.[44]

Turkey

The Syriac community of Turkey identifies as Sūryōyō, historically as Sūrōyō or Sūrōyē (until 20 years ago).[3] The identity characteristics defining the Tur Abdin Syriacs is the Neo-Aramaic language and the Syriac Orthodox Church, and their religious identity correlates to an ethnic identity. Intermarriage between Syriacs and other Christian groups (Armenians and Greeks) is therefore very rare.[45] Unlike some other Syriac Christian religious communities in the Middle East, the Syriacs in Turkey still speak Neo Aramaic languages, specifically the Turoyo language. However, some also speak Turkish, and the community in Mardin traditionally speaks Arabic due to historical reasons.[46] Intermarriage between Syriacs and other Christian groups (Armenians and Greeks) is very rare as well.[45]

It was estimated in 2016 that there were 10,000 Syriac Orthodox in Turkey, with most living in Istanbul.[47] The Tur Abdin region is an historical stronghold of Orthodox Syriacs.[48] Prior to the 1970s and the Turkey-PKK conflict the Tur Abdin region was the epicenter of the Syriac population of Turkey, with 50-70,000 Assyrians and Syriacs being recorded as living there prior to their exodus.[49][50] As of 2012 2,400 live in Tur Abdin,[30] although it might be around 3-5,000 now due to refugees from Iraq and Syria settling there, and Syriacs from the diaspora gradually returning.[51]

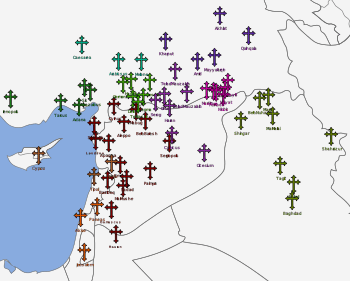

Syria

.svg.png)

The Syriac Orthodox Church is one of eight Christian denominations in the country. The Syriac Orthodox of Syria are most heavily concentrated in Al Hasakah Governorate (or the Jazira region) in villages along the Khabur river such as Tal Tamer where they make up a majority along with other Syriac Christian people groups. They also established the cities of Hasakah and Qamishli[52] in the Governorate after the 1915 massacres, when many Christian people fled Turkey.[52] In the mid-1970s it was estimated that 82,000 Syriac Orthodox lived in the country,[40] but this number is now estimated at 400,000 in 2016 including other Assyrian groups. Part of the reason for this increase is due to an influx of Iraqi refugees after the 2003 invasion along with natural population growth over a 40 year period.[52] Other centers of Syriac Orthodox people outside of Jazira include Fairouzeh, Al-Hafar,[53] Kafr Ram,[54] Maskanah, Al-Qaryatayn, Sadad[55] and Zaidal. Other cities include Damascus, where Their Patriarchate is centered in since 1959.[38], and Homs. The shelling of Homs in 2012 damaged the city and dispersed much of its population, which was until then home to a large Christian community of various denominations.[52]

The Syriac community of Syria has been heavily Arabized, and so do not speak Aramaic languages like their sister community in Turkey.

Iraq

the Syriac Community in Iraq mainly live in Mosul[56] and the Nineveh Plains region of Northern Iraq in the towns of Merki, Iraq, Bartella, Bakhdida, and Karamlesh. An estimated 15–20,000 Syriac Orthodox Christians lived there in 1991.[57] Since the 1960s many have moved south, to Baghdad.[56] The most recent estimations (2014) of their total population in Iraq number between 30–40,000 or 50–70,000.[56] Historically, The Syriacs of the Nineveh Plains and Northern Iraq originated from Tikrit, but immigrated to the north during a period between 1089 and the 1400s due to persecution and a genocide by Timur.[58][59]

Lebanon

Syriac Orthodox Christians are one of several Christian minority groups in Lebanon. A Jacobite community settled in Lebanon among the Maronites after Mongol invasions in the Late Middle Ages, however, this community was either dispersed or absorbed by the Maronites.[60] Assemani (1687–1768) noted that many Maronite families were of Jacobite origin.[60] A Jacobite community was present in Tripoli in the 17th century.[60] The 1915 events forced Syriac Orthodox from Tur Abdin to flee to Lebanon, where they formed communities in the Beirut districts of Zahlah and Musaytbeh.[61] Syriac Refugees from French Cilicia arrived in 1921 to bolster their numbers.[61] In 1944 it was estimated that 3,753 Syriac Orthodox lived in Lebanon.[62] Prior to the Lebanese Civil War (1975–90), there were 65,000 Syriac Orthodox in the country.[61] Half of the community emigrated as a result of violence, with many going to Sweden which protected "stateless people".[61] As of 1987 there were only a few thousand Syriac Orthodox in Lebanon.[63] The Syria conflict has resulted in an influx of Syrian Christian refugees, with many being Syriac Christians.[61]

Diaspora

Language

The Syriac language, of the Semitic Aramaic family, is the literary language of the Syriac Orthodox Church. In Tur Abdin, Turoyo is the Neo-Aramaic dialect spoken by the Syriac Orthodox community. The Turoyo-speaking population prior to the 1915 genocide largely adhered to the Syriac Orthodox Church.[72] In 1970 it was estimated that there were 20,000 Turoyo-speakers still living in the area, however, they gradually migrated to Western Europe and elsewhere in the world.[72] The Turoyo-speaking diaspora is now estimated at 40,000.[72] Today only hundreds of native speakers remain in Tur Abdin.[72] Mlahso, today extinct, was once spoken among the community, particularly in the village with the same name.[73]

The Jacobites adopted Arabic early on; Arabic had become the dominant language of Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt by the 11th century.[74] Syriac Orthodox clergy wrote in Arabic using Garshūni, a Syriac script, as early as the 15th century.[74] They only later adopted the Arabic script.[74] An English missionary in the 1840s noted that the Arabic speech of the Syriacs was intermixed with Syriac vocabulary.[74] They chose Arabic and Muslim-sounding names, while women had Biblical names.[74]

The community speaks Arabic (Mesopotamian and Levantine) and Neo-Aramaic in Arabic countries, and Turkish, Arabic and Neo-Aramaic in Turkey.

Culture

Television

- Suryoyo Sat, Syriac diaspora

- Suroyo TV, Syriac diaspora

Notable people

- Februniye Akyol, Turkish politician and co-mayor of Mardin (as of 2014).[75]

- Diaspora

- Ninos Aho, Syrian-American poet.

- Ibrahim Baylan, Swedish politician, born and raised in Deir Salih, Tur Abdin, Turkey.[76]

- Abgar Barsom, Swedish former footballer.[77]

- Jimmy Durmaz, Swedish footballer.[78] father from Midyat in Turkey.[79]

- David Durmaz, Swedish footballer, family from Midyat, Turkey.[80]

- Yilmaz Kerimo, Swedish politician, born in Turkey.[81]

- Kennedy Bakircioglu, Swedish footballer.[82] family arrived in 1972 from Midyat.

- Sharbel Touma, Swedish footballer, born in Lebanon.[83][84]

- Sarah Ego, German singer.[85]

Gallery

Dioceses of the Syrian Orthodox Church

Dioceses of the Syrian Orthodox Church

See also

References

- ↑ Donabed & Mako 2009; Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 223; Romeny 2012; Romeny 2005

- 1 2 Aryo Makko (2010). The Historical Roots of Contemporary Controversies: National Revival and the Assyrian ‘Concept of Unity’. p. 1.

- 1 2 Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 88.

- ↑ Michael Lapidge (2 November 2006). Archbishop Theodore: Commemorative Studies on His Life and Influence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-521-03210-0.

- ↑ Donabed & Mako 2009.

- ↑ Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 90.

- 1 2 Hämmerli & Mayer 2016, "Suryoye as a Social Category in the Homeland"

- ↑ Hämmerli & Mayer 2016.

- 1 2 Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 21.

- ↑ Taylor 2014, p. 84.

- 1 2 Taylor 2014, p. 87.

- ↑ Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 77.

- ↑ Taylor 2014, p. 201; Romeny 2005

- 1 2 Romeny 2012, p. 195.

- ↑ Saint-Laurent 2015, p. 131.

- ↑ Saint-Laurent 2015, p. 103, 131.

- ↑ Saint-Laurent 2015, p. 103, 106.

- ↑ Saint-Laurent 2015, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ciggaar & Metcalf 2006, p. 108.

- ↑ Ciggaar & Metcalf 2006, p. 123.

- ↑ Ciggaar & Metcalf 2006, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Benjamin Arbel (15 April 2013). Intercultural Contacts in the Medieval Mediterranean: Studies in Honour of David Jacoby. Routledge. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-135-78195-8.

- ↑ Masters 2005, p. 45.

- ↑ Dale A. Johnson. Living as a Syriac Palimpsest. Lulu.com. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-557-40255-7.

- 1 2 Joseph 1983, p. 40.

- 1 2 Joseph 1983, p. 41.

- ↑ Sargon & Ninos Donabed (2010). Assyrians of Eastern Massachusetts. pp. 1–38.

- ↑ Sargon & Ninos Donabed (2010). Assyrians of Eastern Massachusetts. pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Peter C. Phan (21 January 2011). Christianities in Asia. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-1-4443-9260-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Tozman & Tyndall 2012, p. 9.

- ↑ Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 225.

- ↑ Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 222.

- ↑ Jongerden & Verheij 2012, pp. 222–223.

- 1 2 3 Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 223.

- ↑ Hunter 2014, p. 549.

- ↑ Kevorkian 2011.

- ↑ Gaunt, David. Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia during World War I. Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2006, pp. 433–436

- 1 2 3 4 Parry 2010, p. 259.

- ↑ Michael Angold (17 August 2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 513–. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- 1 2 Joseph 1983, p. 110.

- ↑ Sobornost. 28–30. 2006. p. 21.

- ↑ Avraham Sela (5 September 2002). Continuum Political Encyclopedia of the Middle East: Revised and Updated Edition. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-1413-7.

- ↑ Jos M. Strengholt (2008). Gospel in the Air: 50 Years of Christian Witness Through Radio in the Arab World. Boekencentrum. p. 147. ISBN 978-90-239-2280-3.

In the whole Arab World, but mostly in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon, there are an estimated 146,300 Syriac-Orthodox.

- ↑ https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/12/141229-syriac-christians-refugees-midyat-turkey/

- 1 2 Roy, Olivier (2014). Holy Ignorance: When Religion and Culture Part Ways. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-932802-4.

- ↑ Diana Darke (1 May 2014). Eastern Turkey. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 280–. ISBN 978-1-84162-490-7.

- ↑ Bardakçi et al. 2016, p. 169.

- ↑ Aphram I. Barsoum; Ighnāṭyūs Afrām I (Patriarch of Antioch) (2008). The History of Tur Abdin. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-715-5.

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/assyrians-in-iran#pt3

- ↑ Aphram I. Barsoum; Ighnāṭyūs Afrām I (Patriarch of Antioch) (2008). The History of Tur Abdin. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-715-5.

- ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/12/141229-syriac-christians-refugees-midyat-turkey/

- 1 2 3 4 Hunter 2014, pp. 547–548.

- ↑ Batatu, Hanna (1999). Syria's Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics. Princeton University Press. pp. 14, 356. ISBN 0691002541.

- ↑ Said, H. (2015-06-15). "Kafram: An Ancient Syriac Town Famous for Gorgeous Nature Charms". Syrian Arab News Agency. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ↑ Mounes, Maher Al (2015-12-24). "Fearful Christmas for Syrian Christian town threatened by IS". Agence France-Presse. Yahoo News. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- 1 2 3 Hunter 2014, pp. 548–549.

- ↑ Farida Abu-Haidar (1991). Christian Arabic of Baghdad. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-3-447-03209-4.

- ↑ Gibb, H. A. R. (2000). "Takrīt". In Kramers, J. H. Encyclopaedia of Islam 10 (Second ed.). BRILL. pp. 140–141. ISBN 9789004112117.

- ↑ Rassam, Suha (2005). Christianity in Iraq: Its Origins and Development to the Present Day. Gracewing Publishing. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-85244-633-1.

- 1 2 3 Joseph 1983, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hunter 2014, p. 548.

- ↑ A. H. Hourani (1947). Minorities in the Arab World. London.

- ↑ John C. Rolland (2003). Lebanon: Current Issues and Background. Nova Publishers. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-1-59033-871-1.

- 1 2 3 Wozniak 2015.

- ↑ Prakash Shah; Marie-Claire Foblets (15 April 2016). Family, Religion and Law: Cultural Encounters in Europe. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-317-13648-4.

- ↑ United States. Dept. of State; Committee on International Relations; United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Foreign Relations (2005). Annual report, international religious freedom. U.S. G.P.O. p. 342.

- ↑ Gerhard Robbers (2010). Religion and Law in Germany. Kluwer Law International. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-411-3352-6.

- ↑ Marlou Schrover; Willem Schinkel (4 September 2015). The Language of Inclusion and Exclusion in Immigration and Integration. Routledge. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-317-43254-8.

- ↑ John H. Erickson (2010). Orthodox Christians in America: A Short History. Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-19-995132-1.

- ↑ Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 81.

- ↑ R. Khanam (2005). Encyclopaedic Ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia: A-I. Global Vision Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8220-063-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Weninger 2012, p. 697.

- ↑ Jastrow, Otto (1985). "Mlaḥsô: An Unknown Neo-Aramaic Language of Turkey". Journal of Semitic Studies. 30: 265–270. doi:10.1093/jss/xxx.2.265.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joseph 1983, p. 22.

- ↑ "25, Christin - und Bürgermeisterin in Südanatolien". Stern.

- ↑ ""Baylan började hos mig när han var sju år"". SVD.

- ↑ "Syrianske stjärnan Abgar Barsom tackar Syrianska folket". ; Grimlund, Lars (2004). "Artisten Barsom vill vara perfekt". DN.

- ↑ Max Wiman (2011). "Ur ilskan växte årets stora succé".

- ↑ "Jimmy Durmaz ska underlätta flytt - kan skaffa turkiskt pass". Fotbolltransfers.

- ↑ "David Durmaz om mötet med sin nya klubb". Svenska fans. 14 October 2008.

- ↑ "yilmazkerimo". socialdemokraterna.

- ↑ "Zweedse Assyriër in Twente" [Swedish-Assyrian in Twente]. De Pers (in Dutch). 9 March 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ [httsp://www.voetbalzone.nl/doc.asp?uid=128431 "Voormalig FC Twente-speler Touma keert terug naar jeugdliefde"]. 18 November 2010.

- ↑ "Touma kan ersätta Porokara". na.se.

- ↑ "Sarah Ego repräsentiert die syrisch-orthodoxe Kirche". Beth Nahrin. 2012.

Sources

- Bardakçi, Mehmet; Freyberg-Inan, Annette; Giesel, Christoph; Leisse, Olaf (2016). "Like a Drop in the Ocean". Religious Minorities in Turkey: Alevi, Armenians, and Syriacs and the Struggle to Desecuritize Religious Freedom. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-1-137-27026-9.

- Brock, Sebastian P.; Taylor, David G. K. (2001). The Hidden Pearl: At the turn of the third millennium ; the Syrian Orthodox witness. Trans World Film Italia.

- Ciggaar, Krijna Nelly; Metcalf, David Michael (2006). East and West in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean: Antioch from the Byzantine reconquest until the end of the Crusader principality. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1735-4.

- Donabed, Sargon; Mako, Shamiran (2009). "Ethno-cultural and Religious Identity of Syrian Orthodox Christians". Roger Williams University.

- Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 91, 94, 365, 366, 368, 371–379, 887, 901. ISBN 978-0-85773-020-6.

- Hämmerli, Maria; Mayer, Jean-François (2016). Orthodox Identities in Western Europe: Migration, Settlement and Innovation. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-08490-7.

- Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. BRILL. pp. 222–. ISBN 90-04-22518-8.

- Parry, Ken (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Payne Richard, eds. (2016) [2012]. Visions of Community in the Post-Roman World: The West, Byzantium and the Islamic World, 300–1100. Asghate; Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-00136-2.

- Romeny, Bas ter Haar (2012). "Ethnicity, Ethnogenesis and the Identity of Syriac Orthodox Christians". Visions of Community in the Post-Roman World: The West, Byzantium and the Islamic World, 300–1100. Ashgate: 183–204.

- Romeny, Bas ter Haar (2010). Religious Origins of Nations?: The Christian Communities of the Middle East. BRILL. pp. 51–. ISBN 90-04-17375-7.

- Romeny, Bas ter Haar (2005). "From religious association to ethnic community: a research project on identity formation among the Syrian Orthodox under Muslim rule". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. 16: 377–399.

- Saint-Laurent, Jeanne-Nicole Mellon (2015). Missionary Stories and the Formation of the Syriac Churches. University of California Press. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-0-520-96058-9.

- Taylor, William (2014). Narratives of Identity: The Syrian Orthodox Church and the Church of England 1895-1914. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-6946-1.

- Weninger, Stefan (2012). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

Further reading

- Books

- Hunter, Erica C. D. (2014). "The Syrian Orthodox Church". In Leustean, Lucian N. Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. pp. 541–562. ISBN 978-1-317-81866-3.

- Joseph, John (1983). Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East: The Case of the Jacobites in an Age of Transition. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-600-0.

- Tozman, Markus K.; Tyndall, Andrea (2012). The Slow Disappearance of the Syriacs from Turkey and of the Grounds of the Mor Gabriel Monastery. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90268-9.

- Menze, Volker L. (2008). Justinian and the Making of the Syrian Orthodox Church. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-156009-5.

- Ahmet Taşğın; Eyyüp Tanrıverdi; Canan Seyfeli (2005). Süryaniler ve süryanilik. Orient. ISBN 978-975-98974-8-2. (in Turkish)

- Yakup Bilge (1991). Süryanilerin kökeni ve Türkiyeli Süryaniler. Y. Bilge. (in Turkish)

- Aziz Günel (1970). Türk Süryaniler tarihi. Yazan. (in Turkish)

- Gabriyel Akyüz (2001). Osmanlı Devleti'nde Süryani Kilisesi: Osmanlı padişahları tarafından Süryani Kilisesi'nin ruhani liderlerine gönderilen fermanlar. Mardin Kırklar Kilisesi. ISBN 978-975-8233-09-0. (in Turkish)

- The Syrian Jacobites in the Holy City. 1964.

- Journals

- Armbruster, Heidi (2002), Homes in crisis: Syrian orthodox Christians in Turkey and Germany, pp. 17–33

- Atto, Naures (2011), Hostages in the homeland, orphans in the diaspora: identity discourses among the Assyrian/Syriac elites in the European diaspora, Leiden University Press

- Millar, Fergus (2013), "The Evolution of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the Pre-Islamic Period: From Greek to Syriac?", Journal of Early Christian Studies 21.1: 43–92

- O'Mahony, Anthony; Loosley, Emma (16 December 2009). Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East. Routledge. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-135-19371-3.

- Öktem, Kerem (2004), "Incorporating the time and space of the ethnic 'other': nationalism and space in Southeast Turkey in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries", Nations and Nationalism, 10 (4): 559–578

- Palmer, Andrew (1991), "The History of the Syrian Orthodox in Jerusalem", Oriens Christianus (75): 16–43

- Sato, Noriko (2005), "Selective Amnesia: Memory and History of the Urfalli Syrian Orthodox Christians", Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 12.3: 315–333

- Snelders, Bas (2010), Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction: medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area, Leiden Institute for Religious Studies, Faculty of the Humanities

- Thomas, David Richard, ed. (2001), Syrian Christians under Islam: the first thousand years, Brill

- Tozman, Markus K., and Andrea Tyndall (2012), The slow disappearance of the Syriacs from Turkey and of the Grounds of the Mor Gabriel Monastery, III, LIT Verlag Münster

- Van Ginkel, Jan J. (2006), "The perception and presentation of the Arab conquest in Syriac Historiography: How did the changing social position of the Syrian orthodox community influence the account of their historiographers?", The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam, Brill, pp. 171–184

- Weltecke, Dorothea (2003), Contacts between Syriac Orthodox and Latin Military Orders

- Weltecke, Dorothea (2006), The Syriac Orthodox in the principality of Antioch during the Crusader period

- Wozniak, Marta (2015). "From religious to ethno-religious: Identity change among Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden" (PDF). Joint Sessions of Workshops organised by the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR). ECPR.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syriac Orthodox Christians (Middle East). |