Church of the East

| Church of the East | |

|---|---|

| Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ | |

.jpg) Ruins of the ancient city and See of Assur. | |

| Classification | Eastern Christianity |

| Orientation | Syriac Christianity |

| Theology | Nestorianism |

| Head | Catholicos-Patriarchs of the East |

| Region | Middle East, South India, Far East |

| Liturgy |

East Syriac Rite (Liturgy of Addai and Mari) |

| Headquarters | Assur (Ottoman Empire) |

| Founder | Thomas the Apostle, by its tradition |

| Origin |

Apostolic Age, by its tradition Nestorian Schism (431–544) Sasanian Empire |

| Separations | After 1552, divided into: branch united with the Catholic Church and independent branch centered in Alqosh |

| Other name(s) | Nestorian Church |

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Eastern liturgical rites |

|

The Church of the East (Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ Ēdṯāʾ d-Maḏenḥā), also known as the Nestorian Church,[note 1] was an Eastern Christian Church with an independent hierarchy since the Nestorian Schism (431–544), while tracing its history to the late first century CE in the satrapy of Asōristān ruled by the Parthian Empire. From there it spread to other parts of Asia during the late antiquity period and throughout the Middle Ages.

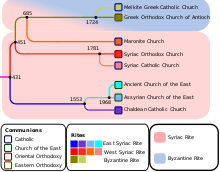

It originated as an eastern branch of Syriac Christianity, and used the East Syriac Rite in liturgy. It developed distinctive theological and ecclesiological traditions, and played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia. Its Schism of 1552 led to a series of internal divisions during the early modern period, and it ultimately branched into the separate Chaldean Catholic Church (in full communion with the Holy See) and the independent Assyrian Church of the East.[1]

The Church of the East was headed by the Patriarch of the East, continuing a line that, according to its tradition, stretched back to the Apostolic Age, and the christianization of Upper Mesopotamia. The Church of the East declared itself separate from the state church of the Roman Empire during the Nestorian Schism in 424–427. Liturgically, the church adhered to the East Syriac Rite (Liturgy of Addai and Mari). Theologically, it adopted the dyophysite doctrine of Nestorianism, which emphasises the separateness of the divine and human natures of Jesus.

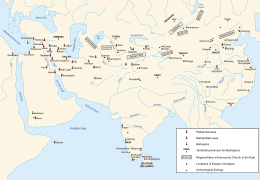

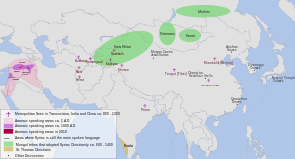

From the 6th century it expanded greatly, establishing communities in India (the Saint Thomas Christians), among the Mongols in Central Asia, and in China, which became home to a thriving community under the Tang dynasty from the 7th to the 9th century. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, at its height, the Church of the East represented the world's largest Christian church in terms of geographical extent, with dioceses stretching from its heartland in Upper Mesopotamia, from the Mediterranean Sea to as far afield as China, Mongolia, Central Asia, Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula and India.

From its peak of geographical extent, the church experienced a rapid period of decline starting in the 14th century, due in large part to outside influences. The Chinese Ming dynasty overthrew the Mongols (1368) and ejected Christians and other foreign influences from China, and many Mongols in Central Asia converted to Islam. The Muslim Turco-Mongol leader Timur (1336–1405) nearly eradicated the remaining Christians in the Middle East; thereafter, Nestorian Christianity remained largely confined to the indigenous communities in Upper Mesopotamia and the Malabar Coast of the Indian subcontinent.

During the patriarchal tenure of Shemon VII Ishoyahb (1539–58), a split occurred when Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa was elected as rival patriarch and entered into full communion with the Catholic Church in 1552, receiving confirmation from the Pope in 1553. After the Schism of 1552, the Church of the East became divided between two branches. After several additional splits and mergers during transitional period from the middle of the 16th century up to beginning of the 19th century, both branches were consolidated as the Chaldean Catholic Church, one of the Eastern Catholic Churches, today with 640,828 members, and the Assyrian Church of the East, today with 323,300 members, along with the Ancient Church of the East, at 100,000. The Indian branch of the Malabar Coast later on became the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church which is in full communion with Rome just as the Chaldean Catholic Church. However, a small faction within the Syro-Malabar group split off and joined with the Assyrian Church of the East in 1701, to form the Chaldean Syrian Church.

Organization and structure

The Church of the East was headed by the Patriarch of the East, an office that traces its origin to the Apostolic Age. The head of the church also bears the title "Catholicos". Like the churches from which it developed, the Church of the East has an ordained clergy divided into the three traditional orders of deacon, priest (or presbyter), and bishop. Also like other churches, it has an episcopal polity: organisation by dioceses, each headed by a bishop and made up of several individual parish communities overseen by priests. Dioceses are organised into provinces under the authority of a metropolitan bishop. The office of metropolitan bishop is an important one, and comes with additional duties and powers; canonically, only metropolitans can consecrate a patriarch.[2] The Patriarch also has the charge of the Province of the Patriarch.

For most of its history the church had six or so Interior Provinces in its heartland in northern Mesopotamia, southeastern Anatolia, and northwestern Iran and an increasing number of Exterior Provinces elsewhere. Most of these latter were located farther afield within the territory of the Sasanian Empire (and later the Caliphate), but very early on, provinces formed beyond the empire's borders as well. By the 10th century, the church had between 20[3] and 30 metropolitan provinces[4] According to John Foster, in the 9th century there were 25 metropolitans[5] including in China and India. The Chinese provinces were lost in the 11th century, and in the subsequent centuries, other exterior provinces went into decline as well. However, in the 13th century, during the Mongol Empire, the church added two new metropolitan provinces in North China, Tangut and Katai and Ong.[4]

Nestorianism and naming conventions

The Church of the East became associated with Nestorianism, a Christological doctrine attributed to Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428–431 AD, which emphasises the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus.[6] Although the "Nestorian" label was initially a theological one, applied to followers of the Nestorian doctrine, it was soon applied to all associated East Syriac Rite churches with little regard for theological consideration. While often used disparagingly in the West to emphasise the Church of the East's connections to a heretical doctrine, many writers of the Middle Ages and since have simply used the label descriptively, as a neutral and conventional term for the church.[4] Other names for the church include "Persian Church", "Syriac" or "Syrian" (often distinguished as East Syriac/Syrian),[4] and "Assyrian".[4]

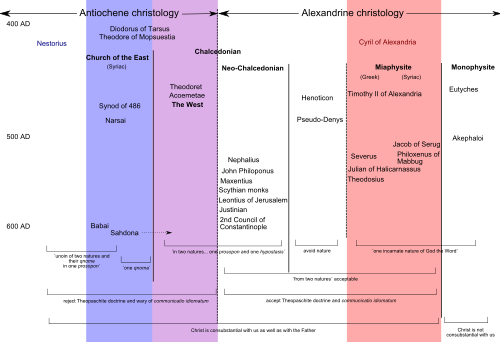

Nestorius's doctrine represented the culmination of a philosophical current developed by scholars at the School of Antioch, most notably Nestorius's mentor Theodore of Mopsuestia. This became a source of controversy when Nestorius publicly challenged usage of the title Theotokos (literally, "Bearer of God") for Mary, mother of Jesus.[7] He suggested that the title denied Christ's full humanity, arguing instead that Jesus had two loosely joined natures, the divine Logos and the human Jesus, and proposed Christotokos (literally, "Bearer of the Christ") as a more suitable alternative title. These statements drew criticism from other prominent churchmen, particularly from Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, leading to the Council of Ephesus in 431, which condemned Nestorius for heresy and deposed him as patriarch.[8] Nestorianism was officially anathematised, a ruling reiterated at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. However, a number of churches, particularly those associated with the School of Edessa in Assyria and northern Mesopotamia, supported Nestorius—though not necessarily the doctrine ascribed to him—and broke with the churches of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. Many of Nestorius' supporters relocated to Sasanian Persia.[3][9] These events are known as the Nestorian Schism.

Based on the works of prominent members of theological schools of Antioch and Nisibis, and shaped by liturgical and linguistic traditions of the East-Syriac rite, christology of the Church of the East was very early faced with particular terminological challenges. Exceptional complexity of Greek theological terminology led to frequent debates and controversies over the use of various terms, both in the Latin West and in Syriac East. Among such terms were: ousia (οὐσία, "essence"), physis (φύσις, "nature"), hypostasis (ὑπόστασις, "substance"), and prosopon (πρόσωπον, "person"). In Syriac language, term physis was translated as kyānâ (ܟܝܢܐ) and hypostasis was translated as qnômâ (ܩܢܘܡܐ). In the Church of the East, the term qnoma (or qnuma) was used to emphasize the dyophysite position in its radical form, by designating a particular hypostasis to each of the two natures of Christ. Official adoption of such theological positions, that were in odds with the Chalcedonian definition, was gradual (starting from the Synod of Beth Lapat in 484). After several oscillations during the 6th century, the process was completed by the beginning of the 7th century, and thus a final christological distinction was created between the Church of the East and the "western" Chalcedonian Churches.[10][11]

In modern times some scholars have sought to avoid the Nestorian label, preferring "Church of the East" or one of the other alternatives. This is due both to the term's derogatory connotations, and because it implies a stronger connection to Nestorian doctrine than may have historically existed. As Wilhelm Baum and Dietmar W. Winkler said, "Nestorius himself was no Nestorian" in terms of doctrine.[12] Even from the beginning, not all churches called "Nestorian" adhered to the Nestorian doctrine; in China, it has been noted that none of the various sources for the local Nestorian church refer to Christ as having two natures. As such, in 2006 an academic conference changed its name from "Research on Nestorianism in China", explaining in the Preface, "it was decided not to keep the term 'Nestorianism' in the title of the future conferences and the present book, but to use the term Church of the East, which is correct and wide enough to cover the whole field of the research".[13]

The 2000 work, The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913, offers an explanation in the first chapter:

The terminology used in this study deserves a word of explanation. Until recently the Church of the East was usually called the "Nestorian" church, and East Syrian Christians were either "Nestorians" or (after the schism of 1552) by the ethnic and geographic misnomer "Chaldeans". During the period covered in this study, the word "Nestorian" was used both as a term of abuse by those who disapproved of the traditional East Syrian theology, as a term of pride by many of its defenders (including Abdisho of Nisibis in 1318, the patriarch Eliya X Yohannan Marogin in 1672, and the patriarch Shimun XVII Abraham in 1842), and as a neutral and convenient descriptive term by others. Nowadays it is generally felt that the term carries a stigma, and students of the Church of the East are advised to avoid its use. In this thesis the theologically neutral adjective "East Syrian" has been used wherever possible, and the term "traditionalist" to distinguish the non-Catholic branch of the Church of the East after the schism of 1552. The modern term "Assyrian", often used in the same sense, was unknown for most of the period covered in this study, and has been avoided.[4]

The Assyrian Church of the East has shunned the "Nestorian" label in recent times. The church's former head, Catholicos-Patriarch Dinkha IV, explicitly rejected the term on the occasion of his consecration in 1976.[14]

Scriptures

The Peshitta, in some cases lightly revised and with missing books added, is the standard Syriac Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition: the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syrian Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Maronites, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

The Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated from Hebrew, although the date and circumstances of this are not entirely clear. The translators may have been Syriac-speaking Jews or early Jewish converts to Christianity. The translation could have been done separately for different texts, and the whole work was probably done by the second century.

The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books (Second Epistle of Peter, Second Epistle of John, Third Epistle of John, Epistle of Jude, Book of Revelation), had become the standard by the early 5th century.

Images

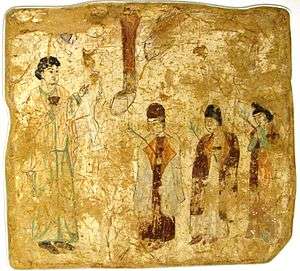

It was often said in the 19th century that the Church of the East was opposed to images of any kind. The cult of the image was never as strong in the Syriac Churches as it was in the Byzantine Church, but they are indeed present in the tradition of the Church of the East.[15] Opposition to religious images eventually became the norm due to the rise of Islam in the region, where it forbade any type of depictions of Saints and biblical prophets. As such, the Church was forced to get rid of their icons.[16]

There is both literary and archaeological evidence for the presence of images in the Church. Writing in 1248 from Samarkand, an Armenian official records visiting a local church and seeing an image of Christ and the Magi. John of Cora (Giovanni di Cori), Latin bishop of Sultaniya in Persia, writing about 1330 of the East Syrians in Khanbaliq says that they had ‘very beautiful and orderly churches with crosses and images in honour of God and of the saints’.[15] Apart from the references, there is a painting of a Nestorian Christian figure, which was discovered by Aurel Stein at the Library Cave of the Mo-kao Caves in 1908, it’s probably an image of Christ.

A Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, from the 13th century, currently resided at the State Library of Berlin. This illustrated manuscript from northern Mesopotamia or Tur Abdin proves that in the 13th century the Church of the East was not yet aniconic.[17] Another Nestorian Gospel manuscript preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which contains an illustration that depicts Jesus Christ in the circle of a ringed cross surrounded by four angels.[18] Three Syriac manuscripts from early 19th century and earlier—they were edited into a compilation titled The Book of Protection by Hermann Gollancz—which contain a number of illustrations more or less crude. These manuscripts prove that the continuation of use of images.

Moreover, a life-size male stucco figure discovered in a church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon from the late 6th century. Beneath this church are found the remains of an earlier church. This discovery proves that the Church of the East also used figurative representations.[17]

.jpg) Fragment of a Nestorian Christian figure, a late-9th-century silk painting preserved in the British Museum.

Fragment of a Nestorian Christian figure, a late-9th-century silk painting preserved in the British Museum. Feast of the Discovery of the Cross, from a 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, preserved in the SBB.

Feast of the Discovery of the Cross, from a 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, preserved in the SBB. An angel announces the resurrection of Christ to Mary and Mary Magdalene, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

An angel announces the resurrection of Christ to Mary and Mary Magdalene, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel. The twelve apostles are gathered around Peter at Pentecost, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

The twelve apostles are gathered around Peter at Pentecost, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel..jpg)

Drawing of a Horseman (Entry into Jerusalem), a lost wall painting from the Nestorian church at Khocho, 9th century.

Drawing of a Horseman (Entry into Jerusalem), a lost wall painting from the Nestorian church at Khocho, 9th century..jpg) Detail of the rubbing of a Nestorian scriptural pillar, 9th century

Detail of the rubbing of a Nestorian scriptural pillar, 9th century.jpg) Detail of the rubbing of a Nestorian scriptural pillar, 9th century

Detail of the rubbing of a Nestorian scriptural pillar, 9th century Nestorian Christian relic (statuette) from Imperial China

Nestorian Christian relic (statuette) from Imperial China

Early history

Although the Nestorian community traced their history to the 1st century, the Church of the East first achieved official state recognition from the Sassanid Empire in the 4th century with the accession of Yazdegerd I (reigned 399–420) to the throne of the Sasanian Empire. In 410 the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, held at the Sasanian capital, allowed the Church's leading bishops to elect a formal Catholicos (leader). Catholicos Isaac was required both to lead the Assyrian Christian community, and to answer on its behalf to the Sasanian emperor.[19][20]

Under pressure from the Sasanian Emperor, the Church of the East sought to increasingly distance itself from the Greek Orthodox Church (at the time being known as the church of the Eastern Roman Empire). Therefore, In 424, the bishops of the Sasanian Empire met in council under the leadership of Catholicos Dadishoʿ (421–456) and determined that they would not, henceforth, refer disciplinary or theological problems to any external power, and especially not to any bishop or Church Council in the Roman Empire.[21]

Thus, the Mesopotamian churches did not send representatives to the various Church Councils attended by representatives of the "Western Church". Accordingly, the leaders of the Church of the East did not feel bound by any decisions of what came to be regarded as Roman Imperial Councils. Despite this, the Creed and Canons of the First Council of Nicaea of 325, affirming the full divinity of Christ, were formally accepted at the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410.[22] The Church's understanding of the term hypostasis differs from the definition of the term offered at the Council of Chalcedon of 451. For this reason, the Assyrian Church has never approved the Chalcedonian definition.[22]

The theological controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus in 431 proved a turning point in the Church's history. The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title Theotokos "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ. (For the theological issues at stake, see Assyrian Church of the East and Nestorianism.)

The Sasanian Emperor, hostile to the Byzantines, saw the opportunity to ensure the loyalty of his Christian subjects and lent support to the Nestorian Schism. The Emperor took steps to cement the primacy of the Nestorian party within the Assyrian Church of the East, granting its members his protection,[23] and executing the pro-Roman Catholicos Babowai in 484, replacing him with the Nestorian Bishop of Nisibis, Barsauma. The Catholicos-Patriarch Babai (497–503) confirmed the association of the Assyrian Church with Nestorianism.

Parthian and Sasanian periods

Christians were already forming communities in Mesopotamia as early as the 1st century under the Parthian Empire. In 266, the area was annexed by the Sasanian Empire (becoming the province of Asōristān), and there were significant Christian communities in Upper Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars.[24] The Church of the East traced its origins ultimately to the evangelical activity of Thaddeus of Edessa, Mari and Thomas the Apostle. While under the jurisdiction of the patriarchate of Antioch, leadership and structure remained disorganised until 315 when Papa bar Aggai (310–329), bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, imposed the primacy of his see over the other Mesopotamian and Persian bishoprics which were grouped together into the Catholicate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon; Papa took the title of Catholicos of the East, or universal leader.[25] This position received an additional title in 410, becoming Catholicos and Patriarch of the East.[26][27]

These early Christian communities in Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars were reinforced in the 4th and 5th centuries by large-scale deportations of Christians from the eastern Roman Empire.[28] However, the Persian Church faced several severe persecutions, notably during the reign of Shapur II (339–79), from the Zoroastrian majority who accused it of Roman leanings.[29] Shapur II attempted to dismantle the Catholicate's structure and put to death some of the clergy including the catholicoi Simeon bar Sabba'e (341),[30] Shahdost (342), and Barba'shmin (346).[31] Afterward, the office of Catholicos lay vacant nearly 20 years (346–363).[32] In 363, under the terms of a peace treaty, Nisibis was ceded to the Persians, causing Ephrem the Syrian, accompanied by a number of teachers, to leave the School of Nisibis for Edessa still in Roman territory.[33] The church grew considerably during the Sasanian period,[3] but the pressure of persecution led the Catholicos Dadisho I in 424 to convene the Synod of Markabta at Seleucia and declare the Catholicate independent from the Patriarch of Antioch.[34]

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Sasanian Empire, mainly around the theological School of Nisibis. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Nestorian schismatics, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Nestorian in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Nestorian Christianity. In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor, Theodore of Mopsuestia, as a spiritual authority.[11] In 489, when the School of Edessa in Mesopotamia was closed by Byzantine Emperor Zeno for its Nestorian teachings, the school relocated to its original home of Nisibis, becoming again the School of Nisibis, leading to a wave of Nestorian immigration into the Sasanian Empire.[35] The Patriarch of the East Mar Babai I (497–502) reiterated and expanded upon his predecessors' esteem for Theodore, solidifying the church's adoption of Nestorianism.[3]

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis, Ctesiphon, and Gundeshapur, and several metropolitan sees, the Church of the East began to branch out beyond the Sasanian Empire. However, through the 6th century the church was frequently beset with internal strife and persecution from the Zoroastrians. The infighting led to a schism, which lasted from 521 until around 539, when the issues were resolved. However, immediately afterward Byzantine-Persian conflict led to a renewed persecution of the church by the Sasanian emperor Khosrau I; this ended in 545. The church survived these trials under the guidance of Patriarch Aba I, who had converted to Christianity from Zoroastrianism.[3]

By the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th, the area occupied by the Church of the East included "all the countries to the east and those immediately to the west of the Euphrates", including the Sasanian Empire, the Arabian Peninsula, Socotra, Mesopotamia, Media, Bactria, Hyrcania, and India; and possibly also to places called Calliana, Male, and Sielediva (Ceylon).[36] Beneath the Patriarch in the hierarchy were nine metropolitans, and clergy were recorded among the Huns, in Persarmenia, Media, and the island of Dioscoris in the Indian Ocean.[37]

The Church of the East also flourished in the kingdom of the Lakhmids until the Islamic conquest, particularly after the ruler al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir officially converted in c. 592.

Islamic rule

After the Sasanian Empire was conquered by Muslim Arabs in 644, the newly established Rashidun Caliphate designated the Church of the East as an official dhimmi minority group headed by the Patriarch of the East. As with all other Christian and Jewish groups given the same status, the Church was restricted within the Caliphate, but also given a degree of protection. Nestorians were not permitted to proselytise or attempt to convert Muslims, but their missionaries were otherwise given a free hand, and they increased missionary efforts farther afield. Missionaries established dioceses in India (the Saint Thomas Christians). They made some advances in Egypt, despite the strong Monophysite presence there, and they entered Central Asia, where they had significant success converting local Tartars. Nestorian missionaries were firmly established in China during the early part of the Tang dynasty (618–907); the Chinese source known as the Nestorian Stele describes a mission under a proselyte named Alopen as introducing Nestorian Christianity to China in 635. In the 7th century, the Church had grown to have two Nestorian archbishops, and over 20 bishops east of the Iranian border of the Oxus River.[38]

The patriarch Timothy I (780–823), a contemporary of the caliph Harun al-Rashid, took a particularly keen interest in the missionary expansion of the Church of the East. He is known to have consecrated metropolitans for Damascus, for Armenia, for Dailam and Gilan in Azerbaijan, for Rai in Tabaristan, for Sarbaz in Segestan, for the Turks of Central Asia, for China, and possibly also for Tibet. He also detached India from the metropolitan province of Fars and made it a separate metropolitan province, known as India.[39] By the 10th century the Church of the East had a number of dioceses stretching from across the Caliphate's territories to India and China.[3]

Nestorian Christians made substantial contributions to the Islamic Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, particularly in translating the works of the ancient Greek philosophers to Syriac and Arabic.[40] Nestorians made their own contributions to philosophy, science (such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Qusta ibn Luqa, Masawaiyh, Patriarch Eutychius, Jabril ibn Bukhtishu) and theology (such as Tatian, Bar Daisan, Babai the Great, Nestorius, Toma bar Yacoub). The personal physicians of the Abbasid Caliphs were often Assyrian Christians such as the long serving Bukhtishu dynasty.[41][42]

Expansion

After the split with the Western World and synthesis with Nestorianism, the Church of the East expanded rapidly due to missionary works during the Medieval period. During the period between 500–1400 the geographical horizons of the Church of the East extended well beyond its heartland in present-day northern Iraq, north eastern Syria and south eastern Turkey. Communities sprang up throughout Central Asia, and missionaries from Assyria and Mesopotamia took the Christian faith as far as China, with a primary indicator of their missionary work being the Nestorian Stele, a Christian tablet written in Chinese script found in China dating to 781 AD. Their most important conversion, however, was of the Saint Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast in India, as they are now the largest group of non ethnically Assyrian Christians on earth, with around 10 million followers when all denominations are added together and their own diaspora is included.[43] The St Thomas Christians were believed by tradition to have been converted by St Thomas, and were in communion with the Church of the East until the end of the medieval period.[44]

India

The Saint Thomas Christian community of Kerala, India, who as per tradition trace their origins to the evangelism of Thomas the Apostle, had a long connection with the Church of the East. The earliest known organised Christian presence in Kerala dates to 295/300 when Nestorian Christian settlers and missionaries from Persia headed by bishop David of Basra settled in the region.[45] The Saint Thomas Christians traditionally credit the mission of Thomas of Cana, a Nestorian from the Middle East, with the further expansion of their community.[46] From at least the early 4th century, the Patriarch of the Church of the East provided the Saint Thomas Christians with clergy, holy texts, and ecclesiastical infrastructure, and around 650 Patriarch Ishoyahb III solidified the church's jurisdiction in India.[47] In the 8th century Patriarch Timothy I organised the community as the Ecclesiastical Province of India, one of the church's Provinces of the Exterior. After this point the Province of India was headed by a metropolitan bishop, provided from Persia, who oversaw a varying number of bishops as well as a native Archdeacon, who had authority over the clergy and also wielded a great amount of secular power. The metropolitan see was probably in Cranganore, or (perhaps nominally) in Mylapore, where the shrine of Thomas was located.[46]

In the 12th century Indian Nestorianism engaged the Western imagination in the figure of Prester John, supposedly a Nestorian ruler of India who held the offices of both king and priest. The geographically remote Malabar church survived the decay of the Nestorian hierarchy elsewhere, enduring until the 16th century when the Portuguese arrived in India. The Portuguese at first accepted the Nestorian sect, but by the end of the century they had determined to actively bring the Saint Thomas Christians into full communion with Rome under the Latin Rite. They installed Portuguese bishops over the local sees and made liturgical changes to accord with the Latin practice. In 1599 the Synod of Diamper, overseen by Aleixo de Menezes, Archbishop of Goa, led to a revolt among the Saint Thomas Christians; the majority of them broke with the Catholic Church and vowed never to submit to the Portuguese in the Coonan Cross Oath of 1653. In 1661 Pope Alexander VII responded by sending a delegation of Carmelites headed by Chaldean Catholics to re-establish the East Syriac rites under an Eastern Catholic hierarchy; by the next year, 84 of the 116 communities returned, forming the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church. The rest, which became known as the Malankara Church, soon entered into communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church; from the Malankara Church has also come the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

China

Christianity reached China by 635, and its relics can still be seen in Chinese cities such as Xi'an. The Nestorian Stele, set up on 7 January 781 at the then-capital of Chang'an, attributes the introduction of Christianity to a mission under a Persian cleric named Alopen in 635, in the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang during the Tang dynasty.[48][49] The inscription on the Nestorian Stele, whose dating formula mentions the patriarch Hnanishoʿ II (773–80), gives the names of several prominent Christians in China, including the metropolitan Adam, the bishop Yohannan, the 'country-bishops' Yazdbuzid and Sargis and the archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan (Chang'an) and Gabriel of Sarag (Loyang). The names of around seventy monks are also listed.[50]

Nestorian Christianity thrived in China for approximately 200 years, but then faced persecution from Emperor Wuzong of Tang (reigned 840–846). He suppressed all foreign religions, including Buddhism and Christianity, causing it to decline sharply in China. A Syrian monk visiting China a few decades later described many churches in ruin. The Church disappeared from China in the early 10th century, coinciding with the collapse of the Tang dynasty and the tumult of the next years (the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period).[51]

Christianity in China experienced a significant revival during the Mongol-created Yuan dynasty, established after the Mongols had conquered China in the 13th century. Marco Polo in the 13th century and other medieval Western writers described many Nestorian communities remaining in China and Mongolia; however, they clearly were not as vibrant as they had been during Tang times.

Mongolia and Central Asia

The Church of the East enjoyed a final period of expansion under the Mongols. Several Mongol tribes had already been converted by Nestorian missionaries in the 7th century, and Christianity was therefore a major influence in the Mongol Empire.[52] Genghis Khan was a shamanist, but his sons took Christian wives from the powerful Kerait clan, as did their sons in turn. During the rule of Genghis's grandson, the Great Khan Mongke, Nestorian Christianity was the primary religious influence in the Empire, and this also carried over to Mongol-conquered China, during the Yuan Dynasty. It was at this point, in the late 13th century, that the Church of the East reached its greatest geographical extent. But Mongol power was already waning, as the Empire dissolved into civil war, and it reached a turning point in 1295, when Ghazan, the Mongol ruler of the Ilkhanate, made a formal conversion to Islam when he took the throne.

Jerusalem and Cyprus

Rabban Bar Sauma had initially conceived of his journey to the West as a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, so it is possible that there was a Nestorian presence in the city ca.1300. There was certainly a recognisable Nestorian presence at the Holy Sepulchre from the 1348 through 1575, as contemporary Franciscan accounts indicate.[53] At Famagusta, Cyprus, a Nestorian community was established just before 1300, and a church was built for them ca.1339.[54][55]

Decline

The end to the Churches expansion came in 1400, when the massacres of Christians by Timur (1336–1405) destroyed many bishoprics, including the ancient Assyrian city and cultural capital of Ashur and from Tikrit, and then completed the eradication of Christians from much of central and southern Mesopotamia/Iraq.

Due to this disaster, the Church of the East, which had previously extended as far as China, was largely reduced to an Assyrian Neo-Aramaic-speaking remnant living in its original heartland in Upper Mesopotamia[56] (With the exception of the St Thomas Christians in India). The Assyrian churches area of influence was from this point up until the Assyrian genocide a triangular area between Amid (modern Diyarbakır), Mêrdîn (modern Mardin), and Edessa to the west; Salmas to the east; Hakkari and Harran to the north; and Mosul, Kirkuk, and Arbela (modern Erbil) to the south; essentially a region comprising, in modern terms, northern Iraq, south east Turkey, north east Syria and the north western fringe of Iran.

Due to the destruction of Assur, The See was moved to the Assyrian town of Alqosh (Kara Akosh) during the 1400s, and Shimun IV Basidi (1437–1493) was appointed Patriarch, establishing a new, hereditary line of succession.[57]

Collapse of the exterior provinces

The "exterior provinces" of the Church of the East, with the important exception of India, collapsed during the second half of the fourteenth century. Although little is known of the circumstances of the demise of the Nestorian dioceses in Central Asia (which may never have fully recovered from the destruction caused by the Mongols a century earlier), it probably stemmed from a combination of persecution, disease, and isolation.

The blame for the destruction of the Nestorian communities east of northern Iraq has often been thrown upon the Turco-Mongol leader of the Timurid Empire, Tamerlane, whose campaigns during the 1390s spread havoc throughout Persia and Central Asia. However, in many parts of Central Asia, Christianity had died out decades before Tamerlane's campaigns. The surviving evidence from Central Asia, including a large number of dated graves, indicates that the crisis for the Church of the East occurred in the 1340s rather than the 1390s. Several contemporary observers, including the papal envoy Giovanni de' Marignolli, mention the murder of a Latin bishop in 1339 or 1340 by a Muslim mob in Almaliq, the chief city of Tangut, and the forcible conversion of the city's Christians to Islam.

At the end of the 19th century, tombstones in two East Syriac cemeteries were discovered and dated in Mongolia. They dated from 1342, and several commemorated deaths during a Black Death outbreak in 1338. In China the last references to Nestorian and Latin Christians date from the 1350s. It is likely that all foreign Christians were expelled from China soon after the revolution of 1368, which replaced Mongol Yuan dynasty rule in China with the xenophobic Ming dynasty.

By the 15th century, Nestorian Christianity was largely confined to the Eastern Aramaic-speaking Assyrian communities of northern Mesopotamia, in and around the rough triangle formed by Mosul and Lakes Van and Urmia - the same general region where the Church of the East had first emerged between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD.[58] Small Nestorian communities were located further west, notably in Jerusalem and Cyprus, but the Malabar Christians of India represented the only significant survival of the once-thriving exterior provinces of the Church of the East.[59]

Schisms and divisions

From the middle of the 16th century, and throughout following two centuries, the Church of the East was affected by several internal schisms. Some of those schisms were caused by individuals or groups who chose to accept union with the Catholic Church. Other schisms were provoked by rivalry between various fractions within the Church of the East. Lack of internal unity and frequent change of allegiances led to the creation and continuation of separate patriarchal lines. In spite of many internal challenges, and external difficulties (political oppression by Ottoman authorities and frequent persecutions by local non-Christians), the traditional branches of the Church of the East managed to survive that tumultuous period, and eventually consolidate during the 19th century in form of the Assyrian Church of the East. At the same time, after many similar difficulties, groups united with the Catholic Church were finally consolidated as the Chaldean Catholic Church.

Schism of 1552

Around the middle of the fifteenth century the patriarch Shemʿon IV Basidi made the patriarchal succession hereditary, normally from uncle to nephew. This practice, which resulted in a shortage of eligible heirs, eventually led to a schism in the Church of the East.[60] The patriarch Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb (1539–58) caused great offence at the beginning of his reign by designating his twelve-year-old nephew Khnanishoʿ as his successor, presumably because no older relatives were available.[61] Several years later, probably because Khnanishoʿ had died in the interim, he designated as successor his fifteen-year-old brother Eliya, the future patriarch Eliya (VI) VII (1558–91).[2] These appointments, combined with other accusations of impropriety, caused discontent throughout the church, and by 1552 Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb had become so unpopular that a group of bishops, principally from the Amid, Sirt and Salmas districts in northern Mesopotamia, chose a new patriarch, electing a monk named Yohannan Sulaqa, the former superior of Rabban Hormizd Monastery near the Assyrian town of Alqosh.[62] However, no bishop of metropolitan rank was available to consecrate him, as canonically required. Franciscan missionaries were already at work among the Nestorians,[63] and they persuaded Sulaqa's supporters to legitimise their position by seeking their candidate's consecration by Pope Julius III (1550–5).[64][2]

Sulaqa went to Rome to put his case in person. At Rome he made a satisfactory Catholic profession of faith and presented a letter, drafted by his supporters in Mosul, which set out his claims to be recognised as patriarch. On April 9, having satisfied the Vatican that he was a good Catholic, Sulaqa was consecrated bishop and archbishop in the basilica of Saint Peter. On April 28 he was recognised as "patriarch of Mosul and Athur" by pope Julius III in the bull Divina disponente clementia and received the pallium from the pope's hands at a secret consistory in the Vatican. These events, which marked the birth of the Chaldean Catholic Church, created a permanent schism in the Church of the East.[64]

Sulaqa was consecrated "patriarch of Mosul and Athur" in Rome in April 1553 and returned to northern Mesopotamia towards the end of the same year.[62] In December 1553 he obtained documents from the Ottoman authorities recognising him as an independent "Chaldean" patriarch, and in 1554, during a stay of five months in Amid, consecrated five metropolitan bishops (for the dioceses of Gazarta, Hesna d'Kifa, Amid, Mardin and Seert). Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb responded by consecrating two more underage members of the patriarchal family as metropolitans for Nisibis and Gazarta. He also won over the governor of ʿAmadiya, who invited Sulaqa to ʿ Amadiya, imprisoned him for four months, and put him to death in January 1555.[62]

The Eliya line of Alqosh

Patriarch Shemon VII Ishoyahb (1539–58), who resided in the Rabban Hormizd Monastery near Alqosh, continued to actively oppose union with Rome, and was succeeded by his nephew Eliya (designated as Eliya "VII" in older historiography, but renumbered as Eliya "VI" in recent scholarly works).[65] During his patriarchal tenure, from 1558 to 1591, the Church of the East preserved its traditional christology and full ecclesiastical independence.[66] His successor Eliya (VII) VIII (1591–1617) negotiated on several occasions with the Catholic Church, in 1605, 1610 and 1615-1616, but without final conclusion.[67] Further negotiations with the Catholic Church were canceled during the patriarchal tenure of his successor Eliya (VIII) IX (1617–1660).[68] David Wilmshurst noted that his successor, patriarch Eliya (IX) X (1660–1700) also was a "vigorous defender of the traditional faith".[69] This line of patriarchs continued throughout the 18th century, residing in the ancient Monastery of Rabban Hormizd, that was eventually attacked in 1743, at the beginning of the Ottoman-Persian War (1743-1746).[70] The Eliya line of patriarchs ended in 1804, with the death of Eliya (XII) XIII Ishoʿyahb.[71][65]

The Shimun line of Qochanis

The parallel line, united with the Catholic Church since 1552, continued under Shimun VIII Sulaqa's successors. First of them was Abdisho IV Maron (1555-1570) who remained in full communion with the Catholic Church. He visited Rome and was confirmed by the pope in 1562.[72] Soon after his death, connections with Catholic Church were loosened for the first time during the patriarchal tenure of Yahballaha V who did not seek confirmation from Rome.[73] His successor Shimun IX Dinkha (1580-1600) restored full communion with the Catholic Church and was officially confirmed by the pope in 1584.[74] After his death, the heredity of the patriarchal office was introduced. Patriarchs of this line commonly used the name Shimun, thus creating the Shimun line.

During the tenure of next patriarch Shimun X Eliyah (1600-1638) ties with Rome were loosened again. In 1616, he signed traditional profession of faith that was not accepted by the pope, leaving the patriarch without confirmation.[75] Hes successor Shimun XI Eshuyow (1638–1656) eventually restored communion with the Catholic Church in 1653, receiving confirmation from the pope.[69] By that time, tendencies towards traditional faith within the Shimun line were growing stronger. Next patriarch Shimun XII Yoalaha sent his profession of faith to the pope, but was deposed soon after that by his bishops because of his Catholic sympathies. The pope tried to intervene on his behalf, but without success.[69]

With the next patriarch Shimun XIII Dinkha (1662-1700), Shimun line definitively broke communion with the Catholic Church. In 1670, he gave a traditionalist reply to an approach that was made from Rome, and by 1672 all connections with the pope were ended.[76][77]. From that time, there were two traditionalist patriarchal lines, the senior Eliya line in Alqosh, and the junior Shimun line in Qochanis.[78]

The Josephite line of Amid

In the Western regions, a new start for the so-called Chaldean Patriarchate began in 1672 when Mar Joseph I, then the metropolitan of Amid under the jurisdiction of the patriarch of the Eliya line, entered in communion with the Catholic Church, separating from the Patriarchal see of Alqosh. In 1681 the Holy See granted him the title of "Patriarch of the Chaldeans deprived of its patriarch" as leader of the Assyrian people who stayed in communion with Rome, and thus forming the third patriarchate of the Church of the East.[79]

All Joseph I's successors took the name of Joseph. The life of this patriarchate was difficult: the leadership was continually vexed by traditionalists, while the community struggled under the tax burden imposed by the Ottoman authorities. Nevertheless, its influence expanded from the original towns of Amid and Mardin toward the area of Mosul, where they relocated the see.

Final consolidation of remaining lines

In 1780, a group seceded from the Eliya hereditary line in Alqosh, and elected Yohannan VIII Hormizd, who made a Catholic profession of faith. He entered full communion with the Roman see and was appointed Archbishop of Mosul. Only after death of Joseph V Augustine Hindi in 1827, Yohannan was recognised as Patriarch by the Pope, in 1830. This merged the various fractions committed to the union with the Catholic Church, thus forming the modern Chaldean Catholic Church.

At the same time, long rivalry between senior Eliya line of Alqosh and junior Shimun line of Qochanis ended in 1804 when last primate of the Eliya line, patriarch Eliya (XII) XIII Ishoyahb (1778-1804), died in the ancient Rabban Hormizd Monastery. His branch did not elect new patriarch, thus enabling patriarch Shimun XVI Yohannan (1780-1820) of the Shimun line to became the sole primate of traditionalist branches.[80][81] Consolidated since 1804, the reunited traditionalist line became known as the Assyrian Church of the East, with its headquarters now located in Chicago in the United States of America.[78]

See also

- Ancient Church of the East

- Assyrian Church of the East

- Chaldean Catholic Church

- Dioceses of the Church of the East to 1318

- Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1318–1552

- Dioceses of the Church of the East after 1552

- Patriarchs of the Church of the East

- List of Patriarchs of the Church of the East

- Schism of the Three Chapters

- Second Council of Constantinople

- Syriac Orthodox Church

- Syriac Christianity

- Christians in the Persian Gulf

Notes

- ↑ Though the "Nestorian" label is well established, it has been contentious. See the Nestorianism and naming conventions section for the naming issue and other designations for the church.

References

Citations

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000.

- 1 2 3 Wilmshurst 2000, p. 21-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Nestorian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wilmshurst 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Foster 1939, p. 34.

- ↑ Silverberg 1972, p. 20–23.

- ↑ Foltz 1999, p. 63.

- ↑ "Cyril of Alexandria, Third epistle to Nestorius, including the twelve anathemas". Monachos.net. Archived from the original on 2012-01-12.

- ↑ "Nestorius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ↑ Meyendorff 1989.

- 1 2 Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 28-29.

- ↑ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 4-5.

- ↑ Hofrichter 2006, p. 11-21.

- ↑ Hill 1988, p. 107.

- 1 2 Parry, Ken (1996). "Images in the Church of the East: The Evidence from Central Asia and China" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 143, 147 & 148. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "The Shadow of Nestorius".

- 1 2 Baumer, Christoph (2016). The Church of the East: An illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity (New Edition). London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 75 and 94. ISBN 978-1-78453-683-1.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Drège (1992). Marco Polo y la Ruta de la Seda. Coll. “Aguilar Universal” (in Spanish). 31. Translated by Mari Pepa López Carmona. Madrid: Aguilar, S. A. de Ediciones. pp. 43 and 187. ISBN 978-84-0360-187-1.

- ↑ Fiey 1970.

- ↑ Chaumont 1988.

- ↑ Hill 1988, p. 105.

- 1 2 Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 354.

- ↑ Outerbridge 1952.

- ↑ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ Ilaria Ramelli, “Papa bar Aggai”, in Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity, 2nd edn., 3 vols., ed. Angelo Di Berardino (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2014), 3:47.

- ↑ Fiey 1967, p. 3–22.

- ↑ Roberson 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ Daniel & Mahdi 2006, p. 61.

- ↑ Foster 1939, p. 26-27.

- ↑ Burgess & Mercier 1999, p. 9-66.

- ↑ Donald Attwater & Catherine Rachel John, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, 3rd edn. (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), 116, 245.

- ↑ Tajadod 1993, p. 110–133.

- ↑ Labourt 1909.

- ↑ Jugie 1935, p. 5–25.

- ↑ Brock 2006, p. 73.

- ↑ Stewart 1928, p. 13-14.

- ↑ Stewart 1928, p. 14.

- ↑ Foster 1939, p. 33.

- ↑ Fiey 1993, p. 47 (Armenia), 72 (Damascus), 74 (Dailam and Gilan), 94–6 (India), 105 (China), 124 (Rai), 128–9 (Sarbaz), 128 (Samarqand and Beth Turkaye), 139 (Tibet).

- ↑ Hill 1993, p. 4-5, 12.

- ↑ Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization

- ↑ Britannica, Nestorian

- ↑ K.C. Zachariah (November 2001). The Syrian Christians of Kerala: Demographic and Socioeconomic Transition in the Twentieth Century (PDF) (Report). Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies.

- ↑ "NSC NETWORK – Early references about the Apostolate of Saint Thomas in India, Records about the Indian tradition, Saint Thomas Christians & Statements by Indian Statesmen". Nasrani.net. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ Frykenberg 2008, p. 102–107, 115.

- 1 2 Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 52.

- ↑ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 53.

- ↑ Ding 2006, p. 149-162.

- ↑ Stewart 1928, p. 169.

- ↑ Stewart 1928, p. 183.

- ↑ Moffett 1999, p. 14-15.

- ↑ Jackson 2014, p. 97.

- ↑ Luke 1924, p. 46–56.

- ↑ Fiey 1993, p. 71.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 66.

- ↑ Frazee 2006.

- ↑ Marthaler 2003, p. 366.

- ↑ Frazee 2006, p. 55.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 345-347.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22.

- ↑ Lemmens 1926, p. 17-28.

- 1 2 Habbi 1966, p. 99-132.

- 1 2 Hage 2007, p. 473.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22, 42 194, 260, 355.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24-25.

- 1 2 3 Wilmshurst 2000, p. 25.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 205, 263.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 263.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22-23.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 23.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 23-24.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24, 315.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 25, 316.

- ↑ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 114, 118, 174-175.

- 1 2 Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 235-264.

- ↑ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 119, 174.

- ↑ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 120, 175.

- ↑ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 316-319, 356.

Sources

- Aboona, Hirmis (2008). Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans: Intercommunal Relations on the Periphery of the Ottoman Empire. Amherst: Cambria Press.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1719). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. 1. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (1775). De catholicis seu patriarchis Chaldaeorum et Nestorianorum commentarius historico-chronologicus. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (2004). History of the Chaldean and Nestorian patriarchs. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press.

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. 1. London: Joseph Masters.

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. 2. London: Joseph Masters.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon.

- Baumer, Christoph (2006). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London-New York: Tauris.

- Becchetti, Filippo Angelico (1796). Istoria degli ultimi quattro secoli della Chiesa. 10. Roma.

- Beltrami, Giuseppe (1933). La Chiesa Caldea nel secolo dell’Unione. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum.

- Binns, John (2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Burgess, Richard W.; Mercier, Raymond (1999). "The Dates of the Martyrdom of Simeon bar Sabba'e and the 'Great Massacre'". Analecta Bollandiana. 117 (1–2): 9-66.

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1902). Synodicon orientale ou recueil de synodes nestoriens (PDF). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Chapman, John (1911). "Nestorius and Nestorianism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1964). "Les Sassanides et la christianisation de l'Empire iranien au IIIe siècle de notre ère". Revue de l'histoire des religions. 165 (2): 165–202.

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1988). La Christianisation de l'Empire Iranien: Des origines aux grandes persécutions du ive siècle. Louvain: Peeters.

- Coakley, James F. (1992). The Church of the East and the Church of England: A History of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Assyrian Mission. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Coakley, James F. (1996). "The church of the East since 1914". The Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 179–198.

- Coakley, James F. (2001). "Mar Elia Aboona und the history of the East Syrian patriarchate". 85: 119–138.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Daniel, Elton L.; Mahdi, Ali Akbar (2006). Culture and customs of Iran. Greenwood Press.

- Ding, Wang (2006). "Remnants of Christianity from Chinese Central Asia in Medieval Ages". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter L. Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Institut Monumenta Serica. pp. 149–162.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1967). "Les étapes de la prise de conscience de son identité patriarcale par l'Église syrienne orientale". L'Orient Syrien. 12: 3–22.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970a). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970b). "L'Élam, la première des métropoles ecclésiastiques syriennes orientales" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 1 (1): 123–153.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970c). "Médie chrétienne" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 1 (2): 357–384.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1979) [1963]. Communautés syriaques en Iran et Irak des origines à 1552. London: Variorum Reprints.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1993). Pour un Oriens Christianus Novus: Répertoire des diocèses syriaques orientaux et occidentaux. Beirut: Orient-Institut.

- Filoni, Fernando (2017). The Church in Iraq. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press.

- Foltz, Richard (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foster, John (1939). The Church of the T'ang Dynasty. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric (2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Giamil, Samuel (1902). Genuinae relationes inter Sedem Apostolicam et Assyriorum orientalium seu Chaldaeorum ecclesiam. Roma: Ermanno Loescher.

- Gulik, Wilhelm van (1904). "Die Konsistorialakten über die Begründung des uniert-chaldäischen Patriarchates von Mosul unter Papst Julius III" (PDF). Oriens Christianus. 4: 261-277.

- Гумилёв, Лев Николаевич (1970). Поиски вымышленного царства: Легенда о государстве пресвитера Иоанна [Searching for an Imaginary Kingdom: The Legend of the Kingdom of Prester John] (in Russian). Москва: Наука.

- Habbi, Joseph (1966). "Signification de l'union chaldéenne de Mar Sulaqa avec Rome en 1553". L'Orient Syrien. 11: 99–132, 199–230.

- Habbi, Joseph (1971a). "L'unification de la hiérarchie chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 2 (1): 121–143.

- Habbi, Joseph (1971b). "L'unification de la hiérarchie chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle (Suite)" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 2 (2): 305–327.

- Hage, Wolfgang (2007). Das orientalische Christentum. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer Verlag.

- Hill, Donald (1993). Islamic Science and Engineering. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hill, Henry, ed. (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto: Anglican Book Centre.

- Hofrichter, Peter L. (2006). "Preface". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter L. Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Institut Monumenta Serica. pp. 11–21.

- Hunter, Erica (1996). "The church of the East in central Asia". The Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 129–142.

- Jackson, Peter (2014) [2005]. The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410. London-New York: Routledge.

- Jakob, Joachim (2014). Ostsyrische Christen und Kurden im Osmanischen Reich des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Münster: LIT Verlag.

- Jenkins, Philip (2008). The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia - and How It Died. San Francisco: HarperOne.

- Jugie, Martin (1935). "L'ecclésiologie des Nestoriens". Échos d'Orient. 34 (177): 5–25.

- Klein, Wassilios (2000). Das nestorianische Christentum an den Handelswegen durch Kyrgystan bis zum 14. Jh. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.

- Labourt, Jérôme (1908). "Note sur les schismes de l'Église nestorienne, du XVIe au XIXe siècle". Journal asiatique. 11: 227–235.

- Labourt, Jérôme (1909). "St. Ephraem". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Lampart, Albert (1966). Ein Märtyrer der Union mit Rom: Joseph I. 1681–1696, Patriarch der Chaldäer. Einsiedeln: Benziger Verlag.

- Lemmens, Leonhard (1926). "Relationes nationem Chaldaeorum inter et Custodiam Terrae Sanctae (1551-1629)". Archivum Franciscanum Historicum. 19: 17-28.

- Luke, Harry Charles (1924). "The Christian Communities in the Holy Sepulchre". In Ashbee, Charles Robert. Jerusalem 1920-1922: Being the Records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council during the First Two Years of the Civil Administratio (PDF). London: John Murray. pp. 46–56.

- Marthaler, Berard L., ed. (2003). "Chaldean Catholic Church (Eastern Catholic)". The New Catholic Encyclopedia. 3. Thompson-Gale. pp. 366–369.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88-141056-3.

- Moffett, Samuel Hugh (1999). "Alopen". Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 14–15.

- Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols. Basil Blackwell.

- Moule, Arthur C. (1930). Christians in China before the year 1550. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Murre van den Berg, Heleen H. L. (1999). "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 2 (2): 235–264.

- Nichols, Aidan (2010) [1992]. Rome and the Eastern Churches: A Study in Schism (2nd revised ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- O’Mahony, Anthony (2006). "Syriac Christianity in the modern Middle East". In Angold, Michael. The Cambridge History of Christianity: Eastern Christianity. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 511–536.

- Outerbridge, Leonard M. (1952). The Lost Churches of China. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Roberson, Ronald (1999) [1986]. The Eastern Christian Churches: A Brief Survey (6th ed.). Roma: Orientalia Christiana.

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the First Journey from China to the West. Kodansha International.

- Rücker, Adolf (1920). "Über einige nestorianische Liederhandschriften, vornehmlich der griech. Patriarchatsbibliothek in Jerusalem" (PDF). Oriens christianus. 9: 107–123.

- Saeki, Peter Yoshiro (1937). The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China. Tokyo: Academy of oriental culture.

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N. (2010). "Nestorius of Constantinople: Condemnation, Suppression, Veneration: With special reference to the role of his name in East-Syriac Christianity". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 62 (3–4): 165–190.

- Silverberg, Robert (1972). The Realm of Prester John. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Stewart, John (1928). Nestorian Missionary Enterprise: A Church on Fire. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- Tajadod, Nahal (1993). Les Porteurs de lumière: Péripéties de l'Eglise chrétienne de Perse, IIIe-VIIe siècle. Paris: Plon.

- Tang, Li; Winkler, Dietmar W., eds. (2013). From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Münster: LIT Verlag.

- Tfinkdji, Joseph (1914). "L' église chaldéenne catholique autrefois et aujourd'hui". Annuaire pontifical catholique. 17: 449–525.

- Tisserant, Eugène (1931). "Église nestorienne". Dictionnaire de théologie catholique. 11. pp. 157–323.

- Vine, Aubrey R. (1937). The Nestorian Churches. London: Independent Press.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1925). "Missio duorum fratrum Melitensium O. P. in Orientem saec. XVI et relatio, nunc primum edita, eorum quae in istis regionibus gesserunt". Analecta Ordinis Praedicatorum. 33 (4): 261-278.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1928). "Catalogue de la bibliothèque syro-chaldéenne du couvent de Notre-Dame des Semences près d'Alqoš (Iraq)". Angelicum. 5: 3-36, 161-194, 325-358, 481-498.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1930). "Les inscriptions de Rabban Hormizd et de N.-D. des Semences près d'Alqoš (Iraq)". Le Muséon. 43: 263-316.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1931). "Mar Iohannan Soulaqa, premier Patriarche des Chaldéens, martyr de l'union avec Rome (†1555)". Angelicum. 8: 187–234.

- Wigram, William Ainger (1910). An Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church or The Church of the Sassanid Persian Empire 100-640 A.D. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Wigram, William Ainger (1929). The Assyrians and Their Neighbours. London: G. Bell & Sons.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited.