Oromo people

The Oromo ethnic flag | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Ethiopia | |

| 25,488,344 (2007)[1] | |

| 22,674 (2009)[2] | |

| 2,030 (2014)[3] | |

| 3,350 (Including those of mixed ancestry) (2016)[4] | |

| Expatriates | unknown |

| Languages | |

|

Mother tongue: Oromo Second language: English | |

| Religion | |

|

Islam ~ 47.5%[5] Ethiopian Orthodox ~ 33%[5] and Protestants traditional religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Afar · Agaw · Amhara · Beja · Saho · Somali · Tigrayans · Tigre · Sidama · other Cushitic peoples[6] | |

The Oromo people (Oromo: Oromoo; Ge'ez: ኦሮሞ, ’Oromo) are an ethnic group inhabiting Ethiopia. They are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia and represent 34.5% of Ethiopia's population.[7] Oromos speak the Oromo language as a mother tongue (also called Afaan Oromoo and Oromiffa), which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. The word Oromo appeared in European literature for the first time in 1893 and then slowly became common in the second half of the 20th century.[8][9]

The Oromo people followed their traditional religion[10] and used the gadaa system of governance.[11][12] A leader elected by the gadaa system remains in power only for 8 years, with an election taking place at the end of that 8 years.[13][14][15] From the 18th century to the 19th century, Oromos were the dominant influence in northern Ethiopia during the Zemene Mesafint period. Various current estimates state that probably around 50-60% of Oromos follow Islam, 30-35% follow Christianity, and fewer than 3% have retained their traditional beliefs.[5][16] They have been one of the parties to historic migrations, and wars particularly with northern Christians and with southern and eastern Muslims, in the Horn of Africa.[17][18][19]

Origins and nomenclature

The origins and prehistory of the Oromo people is unclear, in part because the Oromo people did not have a written history and instead passed on stories orally prior to the 16th century.[20][21] Older and subsequent colonial era documents mention the Oromo people as Galla, but these documents were generally written by members of ethnic groups who were hostile towards them. Anthropologists and historians such as Herbert S. Lewis consider these sources to be fraught with biases, distortions and misunderstandings.[20][21][22]

Historical linguistics and comparative ethnology studies suggest that the Oromo people probably originated around the lakes Shamo (Chamo) and Stephanie (Chew Bahir).[8][22] They are a Cushitic people who have inhabited the East and Northeast Africa since at least the early 1st millennium. The aftermath of the sixteenth century Abyssinian–Adal war led to Oromos being able to occupy lands of the Ethiopian Empire and Adal Sultanate.[23] The Harla were assimilated by the Oromo in Ethiopia.[24]

The first verifiable record mentioning the Oromo people by a European cartographer is in the map made by the Italian Fra Mauro in 1460, which uses the term "Galla".[8] The map was likely drawn after consultations with Tigriyan monks (which produced notable monks such as Abba Bahrey) who visited Italy in 1441 . Galla was a term for a river and a forest, as well as for the pastoral people established in the highlands of southern Ethiopia.[25] This historical information, according to Mohammed Hassen, is consistent with the written and oral traditions of the Somalis. [26]. The historical evidence therefore suggests that the Oromo people were already established in the southern highlands in or before the 15th century, and that at least some Oromo people were interacting with other Ethiopian ethnic groups.[25]

.jpg)

After Fra Mauro's mention, there is a profusion of literature about the peoples of this region including the Oromo, particularly mentioning their wars and resistance to religious conversion, primarily by European sea explorers, Christian missionaries as well as regional writers.[8] Fra Mauro's term Galla is the most used term, however, until the early 20th century. The earliest primary account of Oromo ethnography is the 16th-century "History of Galla" by Christian monk Bahrey who comes from the Sidama country of Gammo, written in the Ge'ez language.[27] He begins his treatise on the Oromo by introducing them in racist terms.[8][28] According to an 1861 book by D'Abbadie, a French explorer who traveled up to Kaffa in 1843, he was told that the word Galla was derived from a "war cry" and used by the Gallas themselves. A journal published by International African Institute suggests it is an Oromo word (adopted by neighbours) for there is a word galla "wandering" in their language.[27][29] The first known use of the word Oromo to refer to this ethnic group is traceable to 1893.[30] The historic term for them has been Galla. This term, stated Juxon Barton in 1924, was in use for these people by Abyssinians and Arabs.[26] The word Galla has been variously interpreted, such as it means "to go home", or it refers to a river named Galla in early Abyssinian tradition.[26]

.svg.png)

Scholarship that followed Barton, states that the label Galla for them, in historic documents, is a stereotype and has been translated by other ethnic groups as "pagan, savage, inferior, enemy",[9][31][32] and "heathen, that is non-Muslim".[33][34] In Afar language, states Morin, Galli (pl. Galla) means "crowd", "foreigners" and carries derogatory connotation "ordinary, commoner" as opposed to moddai or "high descent".[35] Other societies such as the Anuak people refer to all the migrant highlanders consisting of largely Amharas as Galla people while the Tigreans, in the past, refer to Amharas as "half Galla".[36][37] The term Galla was also used by Europeans before the 1974 revolution without any derogatory connotations.[38] The Oromo never called themselves Galla, and resist its use. They traditionally identified themselves by one of their clans (gosas), and in contemporary times have used the common umbrella term of Oromo which connotes "free born people".[39][40]

While Oromo people have lived in this region for a long time, the ethnic mixture of peoples who have lived here is unclear.[41] According to Alessandro Triulzi, the interactions and encounters between Oromo people and Nilo-Saharan groups likely began early. Different groups have attempted to reconstruct a speculative origin theories, wherein either Oromo are presumed "heathen and expansionists who displaced another ethnic group", or the Oromo are presumed to be original people who were "displaced by others". However, persuasive evidence to support various speculations has been missing.[41] The original Oromos increased their numbers through Oromization (Meedhicca, Mogasa and Gudifacha) of conquered people (Gabbaro) from other ethnic groups, and in turn others conquered people from them and converted them to their side.[41] The native ancient names of the territories were replaced by the name of the Oromo clans who conquered it while the people were made Gabbaros (serfs).[41] This, in part, was a Oromo response to preserve their identity, as they as the third major group faced forced mass conversion by the conquering armies of Christian Abyssinians or Islamic Sultanates, often at war with each other.[42][43][44] The word Oromo is derived from Ilm Orma meaning "children of Oromo",[45] or "sons of Men",[46] or "person, stranger".[47]

History

Pre-19th century

Historically, Afaan Oromo-speaking people used their own Gadaa system of governance. Oromos also had a number of independent kingdoms, which they shared with the Sidama people. Among these were the Gibe region kingdoms of Gera, Gomma, Garo, Gumma, Jimma, Leeqa-Nekemte and Limmu-Ennarea.

The earliest known documented and detailed history of the Oromo people was by the Ethiopian monk Abba Bahrey who wrote Zenahu le Galla in 1593, though the synonymous term Gallas was mentioned in maps[8] or elsewhere much earlier.[17][48] After the 16th century, they are mentioned more often, such as in the records left by Abba Pawlos, Joao Bermudes, Jerorimo Lobo, Galawdewos, Sarsa Dengel and others. These records suggest that the Oromo were pastoral people in their history, who stayed together. Their animal herds began to expand rapidly and they needed more grazing lands. They began migrating, not together, but after separating. They lacked kings, and had elected leaders called luba based on a gada system of government instead. By the late 16th century, two major Oromo confederations emerged: Afre and Sadaqa, which respectively refer to four and three in their language, with Afre emerging from four older clans, and Sadaqa out of three.[17] These Oromo confederations were originally based on southern parts of Ethiopia, but started moving north in the 16th century in what is termed as the "Great Oromo Migration".[17][49][50]

According to Richard Pankhurst, an Ethiopia historian, this migration is linked to the first incursions into inland Horn of Africa by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim.[51] According to historian Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst, the migration was one of the consequences of fierce wars of attrition between Christian and Muslim armies in the Horn of Africa region in the 15th and 16th century which killed a lot of people and depopulated the regions near the Galla lands, but also probably a result of droughts in their traditional homelands. Further, they acquired horses and their gada system helped coordinate well equipped Oromo warriors who enabled fellow Oromos to advance and settle into newer regions starting in the 1520s. This expansion continued through the 17th century.[52][49]

Both peaceful integration and violent competition between Oromos and other neighboring ethnicities such as the Amhara, Sidama, Afar and the Somali affected politics within the Oromo community.[51][50] Between 1500 and 1800, there were waves of wars and struggle between highland Christians, coastal Muslim and polytheist population in the Horn of Africa. This caused major redistribution of populations. The northern, eastern and western movement of the Oromos from the south around 1535 mirrored the large-scale expansion by Somalis inland. The 1500–1800 period also saw relocation of the Amhara people, and helped influence contemporary ethnic politics in Ethiopia.[53]

According to oral and literary evidence, Borana Oromo clan and Garre Somali clan mutually victimized each other in seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly near their eastern borders. There were also periods of relative peace.[54][55] According to Günther Schlee, the Garre Somali clan replaced the Borana Oromo clan as the dominant ethnic group in this region. The Borana violence against their neighbors, states Schlee, was unusual and unlike their behavior inside their community where violence was considered deviant.[56]

Slavery

Before the 19th-century

Oromo, along with Sidama, were the main targets for slaves before the 16th-century. Warfare, kidnapping and judicial sentencing were some reasons for the enslavement of the Oromo people. In certain cases "pastoralist Oromo enslaved settled Oromo", and as some Oromo converted to Islam or Christianity, the relationships within the Oromo societies fissured. According to Rudolph Ware, a professor of history specializing in Africa, slavery had become so central to the political economy in the Horn of Africa that the Oromo had little choice.[57] The slavery historian Paul E. Lovejoy concurs, and states, "slavery was fundamental to the social, political and economic order of the northern savanna, Ethiopia and the East African coast for several centuries before 1600".[58]

The slaves were classified into two groups according to Amhara color conventions:[57] "red" slaves, who were light-brown in complexion and mostly from the Cushitic-speaking populations of southern and southwestern Ethiopia, and "black" slaves called Bareya or Shanqalla ("Negro"), who were from the Sudanese-Ethiopian border – the western fringes of the Christian Ethiopia at the time.[59][60] The "red" slaves were more expensive and exported, while the "black" slaves were kept domestically such as by Christian Abyssinians.[57][61] The bulk of red habasha slaves were Oromos along with the Sidama.[57] The Cushitic-speaking Oromos formed the expensive and the bulk of 'Ethiopian' slaves exported to Arabian peninsula and Persian Gulf regions,[62][14] to Ottoman Empire markets,[63] to Egypt and elsewhere.[57] Young female Oromo slaves served as concubines and household workers,[64] while males were in demand for private armies and servile labor.[65]

Oromos too enslaved other ethnic groups. According to a report by Bermudes, in the 16th century, Oromos during their wars were fierce and cruel, mutilating and enslaving the people in the regions they conquered. Emperor Galawdewos battled with Oromos without much success and sought Portuguese help.[66][67] In the era of Imam Ahmad, according to Bahrey's records, Oromo Luba 'tribes' made war in Dawaro against Adal Mabraq, devastating the region and occupying it. They also took over Fatagar and Faj, forcing its previous inhabitants into slavery.[68][67]

The pagan Galla and animist Sidama or Agew slaves made up the slave caravans coming out of Ethiopia, as slavers avoided Christian or Muslim slaves.[14][15] The central Amhara provinces were a part of major Afar slave caravan trade routes from the southern and southwestern Galla, Sidama and Gurage regions to the northern and eastern Ethiopia.[69] Thousands of slaves were exported every year by Jabarti, Jalaba, Afar, Somali and Arab merchants as the income from this trade was lucrative.[14][15] According to Ira M. Lapidus, a professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic History, the Ethiopian slave trade benefited the Muslims, and increased the Islamization of the Oromo people.[15]

Slavery in the 19th-century and early 20th-century

In the first decades of the 19th century, three Oromo monarchies, Enarya, Goma and Guma, rose to prominence.[50] The collective area was known as Galla-land and comprised most of central and southern Ethiopia, including lands now held by other ethnic regions.[70] In the general view of Oromo people's role in Ethiopia, one of the Oromo leaders named Ras Gobana Dacche led the development of modern Ethiopia and the political and military incorporation of more territories into Ethiopian borders. Gobana, under the authority of Amhara ruler Emperor Menelik II, incorporated several and brought large sections of the Horn of Africa into a centralized Ethiopian state.[71][72]

The demand for Ethiopian slaves in Arabia, the Persian Gulf region, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere far outpaced the supply in the first half of the 19th century, leading slavers such as the Jabarti caravans to penetrate deeper into Ethiopia.[73][74] According to Richard Pankhurst, a significant part of the extensive slave trading in early 19th-century, from many parts of Ethiopia to coastal regions of Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Sudan and Egypt, came from the Oromo regions.[75] In the second half of nineteenth century, Ethiopian slaves, called Habash, continued to be in high demand in Arabian and Middle Eastern markets as servants, treasurers and bodyguards for merchants and rulers, or as concubines and wives for the well-to-do.[76][77] These slaves also came mainly from Oromo and Sidama country.[76][77] Slaves were brought from slave markets in Jimma, Basso and elsewhere, and their caravans sent thousands to the ports of Matamma, Massawa and Tajura on the Red Sea.[76]

By the early nineteenth century Asandabo, Saqa, Hermata and Billo were the primary slave markets of Guduru, Limmu-Enaria, Jimma and Leqa-Naqamite respectively where long distance slave caravans and local traders met.[78][79] Merchant Villages adjacent to these major markets of the south were invariably full of slaves in which the upper classes exchanged them for the imported goods they coveted.[12] Slave trading for those states was the primary source of revenue. Many were raided from neighboring territories,[80] in other cases Oromo took other Oromo as captives for slave trading,[81] sometimes Oromo people were sentenced into slavery for minor crimes such as tax arrears,[82] and sold by Oromo and Sidama rulers.[83][77][84] Slaves from these major markets of the south were walked northward to large distribution markets like Basso in Gojjam, Aliyu Amba and Abdul Resul in Shewa. There, the kingdoms taxed the transaction before the slaves were exported.[80][76]

Coastal and border towns such as Massawa, Tajura and Metemma, as well as merchant centers such as in Gondar and Debarq had custom officials called Nagadras who collected taxes on each slave.[76] A study of slave shipping records shows that over 3,300 slaves were exported every year from northern routes from Ethiopia, while over 4,200 slaves exported annually from southern routes.[77] On average, available records suggest that 15,000 new slaves every year were produced in southern Ethiopia, the region inhabited by Oromo and Sidama people. Of these, Jimma alone exported up to 4,000 annually and slave trading was the largest export item in terms of value for the state,[85] while Gojjam produced 7,000.[77][80]

According to Francesca Declich, there was a flourishing market in Somalia for Oromo slaves in 19th and early 20th centuries, both in agricultural areas surrounding the Shebelle River, as well as in urban and pastoral settings. These Oromo slaves were either kidnapped from their home regions, captured in raids or were captives who had fought back.[86] The records from the Somali markets, such as in Mogadishu, indicate that the highest price for slaves were paid for "Galla woman" in the 15–20 year age group meant to work as a concubine, while a Galla teenage for domestic work and girl child in the age group of 8–10 attracted much lower prices.[87]

According to colonial British consulate records, slaves were exported from Oromo lands in particular, but also other parts of Ethiopia. In 1866 alone thousands of Christians were exported from Taka and Metema, which were key outlets for Ethiopian slave exports.[88] Since religious law did not permit Christians to participate in the trade, Muslims dominated the slave trade, often going farther and farther afield to find supplies.[80] In the centralized Oromo states of Gibe valleys and Didesa, the agricultural and industrial sectors mainly relied on slave labour. Slave labour became so large that in states such as Gibe, Jimma, Gera and Janjero, slaves constituted a third to two-thirds of the total population.[89][90]

The inter-clan relationships within the Oromo people, as well as their relationship with the Amhara people who are the second largest ethnic group, have been historically complicated. There was inter-clan fighting within Oromo.[91] Over 450 years, through the 19th century, states Donald N. Levine, the warfare between Amhara and Oromo had been "more or less continuous". In the southern and western regions, the Oromo-Amhara wars have been as terribly destructive as those between Amhara and Muslim Sultanates in the east.[92] In certain regions, some Oromo groups formed an alliance and cooperated with Amhara-Tirgrean authorities.[93]

The inter-relationship between Oromo and Amhara peoples has been a subject of dispute, some suggesting evidence of integration while others suggesting on-going abuse that continued through the 20th century. From one perspective, ethnically mixed Ethiopians with Oromo background made up a small percentage of Ethiopian generals and leaders.[94] The Wollo Oromo (particularly the Raya Oromo and Yejju Oromo) were early Oromo holders of power among the increasingly mixed Ethiopian state. The later north-to-south movement of central power in Ethiopia led to Oromos in Shewa holding power in Ethiopia together with the Shewan Amhara.[95]

Formation of modern Ethiopia

The accounts of integration of Oromo people into a united Ethiopian nation vary widely.[96]:39–41 By one account it was violent and forced. A school of scholars state that during the conquest of the southern territories that created the modern Ethiopia, the neftenya-gabbar system brutally subordinated the Oromos,[96] Menelik's Army carried out mass atrocities during the conquest against civilians and combatants including torture, mass killings and large-scale slavery.[18][97] Large-scale atrocities were also committed against the Dizi people and the people of the Kaficho kingdom.[98][99] Some estimates for the number of Southern people (Oromos, Dizi people, Kaffa, Shanqella) killed as a result of the conquest from war, famine and atrocities go into the millions.[18][100][101]

Other accounts disagree. The Russian writer Aleksandr Bulatovich, for example, travelled to Ethiopia around the start of the 20th century, and he stated that in territories incorporated peacefully like Jima, Leka and Wolega, the former order had been preserved without interference in Oromo self-government. He said that in areas incorporated after war, the assigned rulers treated the people lawfully and justly, and did not violate their religious beliefs .[102][103] He explained the deaths as a consequence of many factors such as famine and diseases that ravaged this period of Ethiopian history.[104][105][106]

In some accounts, the relationship between the two largest ethnic groups of Ethiopia, Oromo and Amhara, has been described as "Abyssinian feudal colonialism". According to Mekuria Bulcha, for example, Oromo were colonized by Amhara just like European colonialists in the pre-20th century period. The Abyssinian general Ras Darge, according to these accounts, ordered "Arsi mutilation". Oromo populations who resisted Amhara occupation were subject to amputations and disfigurement. Villages were decimated. By 1901, parts of the Oromo territory were reduced to a third or half of their original population.[107] According to Akbar Ahmad, Amharic sayings such as "Saw naw Galla? (is it human or Galla?)" highlighted Amhara's contempt towards the Oromo.[108] In the 1960s, political disputes emerged with reports of discrimination in educational opportunities for Oromo by Amhara leaders.[109]

Others disagree with the colonial thesis. According to Paulos Milkias and Getachew Metaferia, Amhara and Oromo have shared the same geographical and historical space; they are intertwined culturally, economically and politically; millions of people trace their origin from both groups; elite Oromos were the regional kingmakers in, e.g., Gondar and Shewa; and intermarriage between Amhara and Oromo ruling elites was and is extensive. Thousands of Amharas from nobles to peasants and from educated to illiterate served loyally under Oromo ministers and generals, which, Milkias and Metaferia state, "would be like having thousands of Englishmen, nobles and commoners loyally serving African ministers and generals in England". All this is inconsistent with the "Amhara colonized Oromo" thesis, as it neither happened nor can happen under a colonial system.[110]

According to some scholars, Oromo became part of the Ethiopian nobility without losing their identity.[111][112][113] Others state that the marginalization of the Oromos during Amhara rule led many to change their names to blend in with the Amhara population.[114]

According to Atsuko Karin Matsuoka and John Sorenson, there was large-scale cruel exploitation of Oromo peasants in the 19th and 20th centuries, but the situation was more complex because some Oromos crossed ethnic lines and collaborated with the Abyssinian forces. This period also marked individual Oromos reaching high ranks in the Ethiopian military, and several royal family members of this era were partially of Oromo descent.[96]:40–42[115][116] For example, Iyasu V was the designated but uncrowned Emperor of Ethiopia (1913–1916), while Haile Selassie I was the crowned and generally acknowledged Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974.[117] Other Oromo people reached high positions in the emerging Ethiopia.[118][119]

The Oromo traditionalists state that those who rose to powerful positions did so by rejecting their "Oromo-ness": rejecting their culture and adopting the other culture.[96] Some in Ethiopia see Oromo as integral architects and a part of one nation, while others see a long history of denigration, treatment as "primitive barbarians" by Amhara and other ethnic groups, and a need to "resurrect Oromo culture and history".[96]:40–47[120]

Demographics

The Oromos are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia (34.5% of the population) and in Ethiopia there are 25,488,344 Oromos.[7] Their population is dispersed over a large region. They speak 74 ethnically diverse language groups. About 95% are settled agriculturalists and nomadic pastoralists, practising archaic farming methods and living at subsistence level. A few live in the urban centres.

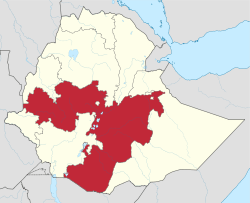

Oromos today are concentrated in the Oromia region in central Ethiopia, which is the largest region in the country in terms of both population and size. They are present in large numbers in other central, western and southern provinces of Ethiopia. Group members also have a notable presence in northern Kenya in the Marsabit County, and in the former Wollo and Tigray provinces of Ethiopia.[121]

Subgroups

The Oromo are divided into two major branches that break down into an assortment of clan families. From west to east. The Borana Oromo, also called the Boran, are a pastoralist group living in southern Ethiopia (Oromia) and northern Kenya.[122][123] The Boran inhabit the former provinces of Shewa, Welega, Illubabor, Kafa, Jimma, Sidamo, northern and northeastern Kenya, and a small refugee population in some parts of Somalia.

Barentu/Barentoo or (older) Baraytuma is the other moiety of the Oromo people. The Barentu Oromo inhabit the eastern parts of the Oromia Region in the Zones of Mirab Hararghe or West Hararghe, Arsi Zone, Bale Zone, Debub Mirab Shewa Zone or South West Shewa, Dire Dawa region, the Jijiga Zone of the Somali Region, Administrative Zone 3 of the Afar Region, Oromia Zone of the Amhara Region, and are also found in the Raya Azebo woreda in the Tigray Region.

Language

The Oromo speak the Oromo language as a mother tongue (also known as Afaan Oromoo and Oromiffa). It belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family.

According to Ethnologue, there are around 17,465,900 Oromo speakers worldwide.[124]

The Oromo language is divided into four main linguistic varieties: Borana-Arsi-Guji Oromo, Eastern Oromo, Orma and West Central Oromo.[124]. Onesimos Nesib was a founder of the Oromo modern literature.[125]

Modern writing systems used to transcribe Oromo include the Latin script. The Ethiopic script had previously been used by Oromo communities in west-central Ethiopia up until the 1990s.[126] Additionally, the Sapalo script was historically used to write Oromo. It was invented by the Oromo scholar Sheikh Bakri Sapalo (also known by his birth name, Abubaker Usman Odaa) during the 1950s.[127][128]

Religion

Christianity was adopted in Ethiopia early in 340 CE by the Kingdom of Axum. Ethiopia was an early Christian kingdom that remained in power through the modern era. Islam arrived from the coastal region during the medieval era, across the Gulf of Aden, and led to the creation of warring Islamic sultanates such as Hadiya, Bali, Fatagar, Dawaro and Adal. These kingdoms and sultanates ruled or influenced the history of Oromo people.[43][44] The influential 30-year war from 1529 to 1559 between the three parties – the Oromo, the Christians and the Muslims – dissipated the political strengths of all three. The religious beliefs of the Oromo people evolved in this socio-political environment.[43] In the 19th century and first half of the 20th century, neither the Muslim-controlled areas, nor the areas where the Ethiopian Orthodox Church was dominant, would allow Protestant or Catholic missionaries to proselytize among them, and these missions focused their efforts in the southern provinces of Greater Ethiopia where Oromo people following the traditional religions lived.[129]

In the 2007 Ethiopian census for Oromia region, which included both Oromo and non-Oromo residents, there was a total of 13,107,963 followers of Christianity (8,204,908 Orthodox, 4,780,917 Protestant, 122,138 Catholic), 12,835,410 followers of Islam, 887,773 followers of traditional religions, and 162,787 followers of other religions.[130]

According to a 2009 publication of Association of Muslim Social Scientists and International Institute of Islamic Thought, "probably just over 60% of the Oromos follow Islam, over 30% follow Christianity and less than 3% follow traditional religion".[16]

According to a 2016 estimate by James Minahan, about half of the Oromo people are Sunni Muslim, a third are Ethiopian Orthodox, and the rest are mostly Protestants or follow their traditional religious beliefs.[5] The traditional religion is more common in southern Oromo populations, Christianity more common in and near the urban centers, while Muslims are more common near the Somalian border and in the north.[121]

Society and culture

Gadaa

Oromo people were traditionally a culturally homogeneous society with genealogical ties.[131] They governed themselves in accordance with Gadaa (literally "era"), an outstanding democratic socio-political system long before the 16th century, when major three party wars commenced between them and the Christian kingdom to their north and Islamic sultanates to their east and south. The Gadaa system elected males from five Oromo miseensa (groups), for a period of eight years, for various judicial, political, ritual and religious roles. Retirement was compulsory after the eight year term, and each major clan followed the same Gadaa system.[131] Women and people belonging to the lower Oromo castes were excluded.[132] A male born in the upper Oromo society went through five stages of eight years, where his life established his role and status for consideration to a Gadaa office.[131]

Under Gadaa, every eight years, the Oromo would choose by consensus an Abbaa Bokkuu responsible for justice, peace, judicial and ritual processes, an Abbaa Duulaa responsible as the war leader, an Abbaa Sa'aa responsible as the leader for cows, and other positions.[133]

Social stratification

Like other ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa and East Africa, Oromo people regionally developed social stratification consisting of four hierarchical strata. The highest strata were the nobles called the Borana, below them were the Gabbaro (some 17th to 19th century Ethiopian texts refer them as the dhalatta). Below these two upper castes were the despised castes of artisans, and at the lowest level were the slaves.[134][135]:254–256

In the Islamic Kingdom of Jimma, the Oromo society's caste strata predominantly consisted of endogamous, inherited artisanal occupations.[136][137][138] Each caste group has specialized in a particular occupation such as iron working, carpentry, weapon making, pottery, weaving, leather working and hunting.[139][137]

Each caste in the Oromo society had a designated name. For example, Tumtu were smiths, Fuga were potters, Faqi were tanners and leatherworkers, Semmano were weavers, Gagurtu were bee keepers and honey makers, and Watta were hunters and foragers.[136][140][141] While slaves were a stratum within the society, many Oromos, regardless of caste, were sold into slavery elsewhere. By the 19th century, Oromo slaves were sought after and a major part of slaves sold in Gondar and Gallabat slave markets at Ethiopia-Sudan border, as well as the Massawa and Tajura markets on the Red Sea.[142][143]

Calendar

The Oromo people developed a luni-solar calendar, which likely dates from a pre-16th century period and before the great migration because different geographically and religiously distinct Oromo communities use the same calendar. This calendar is sophisticated and similar to ones found among the Chinese, the Hindus and the Mayans. It was tied to the traditional religion of the Oromos, and used to schedule the Gadda system of elections and power transfer.[144]

The Borana Oromo calendar system was once thought to be based upon an earlier Cushitic calendar developed around 300 BC found at Namoratunga. Reconsideration of the Namoratunga site led astronomer and archaeologist Clive Ruggles to conclude that there is no relationship.[145] The new year of the Oromo people, according to this calendar, falls in the month of October.[146] The calendar has no weeks but a name for each day of the month. It is a lunar-stellar calendar system.[147][148]

Oromumma

Some modern authors such as Gemetchu Megerssa have proposed the concept of Oromumma, or "Oromoness" as a cultural common between Oromo people.[149] The word is derived by combining "Oromo" with the Arabic term "Ummah" (community). However, according to Terje Østebø and other scholars this term is a neologism from the late 1990s and has been questioned to its link to Oromo ethno-nationalism and Salafi Islamic discourse, in their disagreement with Christian Amhara and other ethnic groups.[150]

The Oromo people, depending on their geographical location and historical events, have variously converted to Islam, to Christianity, or remained with their traditional religion. According to Gemetchu Megerssa, the subjective reality is that "neither traditional Oromo rituals nor traditional Oromo beliefs function any longer as a cohesive and integral symbol system" for the Oromo people, not just regionally but even locally.[149] The cultural and ideological divergence within the Oromo people, in part from their religious differences, is apparent from the constant impetus for negotiations between broader Oromo spokespersons and those Oromo who are Ahl al-Sunna followers, states Terje Østebø.[151] The internally evolving cultural differences within the Oromos have led some scholars such as Mario Aguilar and Abdullahi Shongolo to conclude that "that a common identity acknowledged by all Oromo in general does not exist".[152]

Contemporary era

Ethiopian Civil War

In 1973, Oromo discontent with their position led to the formation of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), which began political agitation in the Oromo areas. That year there was also a catastrophic famine in which over one quarter of a million people died from starvation before the government recognised the disaster and permitted relief measures. The majority who died were Oromos and Amharas from Wollo, Afars and Tigrayans. There were strikes and demonstrations in Addis Ababa in 1974; and in February of that year, Haile Selassie’s government was replaced by the Derg, a military junta led by Mengistu Haile Mariam (a mixed Ethiopian with ethnic Konso heritage); but the Council was still Amhara-dominated, with only 25 non-Amhara members out of 125. In 1975 the government declared all rural land State-owned, and announced the end of the tenancy system. However, much of the benefit of this reform was counteracted by compulsive collectivization, State farms and forced resettlement programmes.

In 1991, the Derg was replaced by the EPRDF. Initially, Oromo intellectuals and the OLF joined the transitional government alongside EPRDF. However, the TPLF branch of EPRDF created an Oromo party (OPDO) to marginalized the OLF and eventually expel it from the country. Despite increased harassment on Oromos, the OPDO presided over the advancement of Oromo language and culture over the last two decades. The TPLF is widely known to use this progress in Oromo cultural and linguistic empowerment as an achievement and a mandate for EPRDF rule the nation. However, most Oromos still do not believe they have political rights and many of them support the OLF and other opposition parties including the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC).

Human rights issues

In December 2009, a 96-page report titled Human Rights in Ethiopia: Through the Eyes of the Oromo Diaspora, compiled by the Advocates for Human Rights, documented human rights violations against the Oromo in Ethiopia under three successive regimes: the Ethiopian Empire under Haile Selassie, the Marxist Derg and the current Ethiopian government of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), dominated by members of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and which was accused to have arrested approximately 20,000 suspected OLF members, to have driven most OLF leadership into exile, and to have effectively neutralized the OLF as a political force in Ethiopia.[153]

According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Oromia Support Group (OSG) recorded 594 extra-judicial killings of Oromos by Ethiopian government security forces and 43 disappearances in custody between 2005 and August 2008.[154]

Starting in November 2015, during a wave of mass protests, mainly by Oromos, over the expansion of the municipal boundary of the capital, Addis Ababa, into Oromia, over 500 people have been killed and many more have been injured, according to human-rights advocates and independent monitors.[155][156] The protests have since spread to other ethnic groups and encompass wider social grievances.[156] Ethiopia declared a state of emergency in response to Oromo and Amhara protests in October 2016.

Political organizations

Most Oromos do not have political unity today due to their historical roles in the Ethiopian state and the region, the spread-out movement of different Oromo clans, and the differing religions inside the Oromo nation.[157] Accordingly, Oromos played major roles in all three main political movements in Ethiopia (centralist, federalist and secessionist) during the 19th and 20th century. In addition to holding high powers during the centralist government and the monarchy, the Raya Oromos in the Tigray regional state played a major role in the "Weyane" revolt, challenging Emperor Haile Selassie I's rule in the 1940s.[158] Simultaneously, both federalist and secessionist political forces developed inside the Oromo community.

At present a number of ethnic-based political organizations have been formed to promote the interests of the Oromo. The first was the Mecha and Tulama Self-Help Association founded in January 1963, but disbanded by the government after several increasingly tense confrontations in November, 1966.[159] Later groups include the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), Oromo Federalist Democratic Movement (OFDM), the United Liberation Forces of Oromia (ULFO), the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Oromia (IFLO), the Oromia Liberation Council (OLC), the Oromo National Congress (ONC, recently changed to OPC) and others. Another group, the Oromo People's Democratic Organization (OPDO), is one of the four parties that form the ruling Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) coalition. However, these Oromo groups do not act in unity: the ONC, for example, was part of the United Ethiopian Democratic Forces coalition that challenged the EPRDF in the Ethiopian general elections of 2005.

A number of these groups seek to create an independent Oromo nation, some using armed force. Meanwhile, the ruling OPDO and several opposition political parties in the Ethiopian parliament believe in the unity of the country which has 80 different ethnicities. But most Oromo opposition parties in Ethiopia condemn the economic and political inequalities in the country. Progress has been very slow, with the Oromia International Bank just recently established in 2008, though Oromo-owned Awash International Bank started early in the 1990s. The first private Afaan Oromoo newspaper in Ethiopia, Jimma Times, also known as Yeroo, was recently established, but it has faced a lot of harassment and persecution from the Ethiopian government since its beginning.[160][161][162][163][164] Abuse of Oromo media is widespread in Ethiopia and reflective of the general oppression Oromos face in the country.[165] University departments in Ethiopia did not establish a curriculum in Afaan Oromo until the late 1990s because they lacked the technical expertise and resources.

Various human rights organizations have publicized the government persecution of Oromos in Ethiopia for decades. In 2008, OFDM opposition party condemned the government's indirect role in the death of hundreds of Oromos in western Ethiopia.[166] According to Amnesty International, "between 2011 and 2014, at least 5000 Oromos have been arrested based on their actual or suspected peaceful opposition to the government. These include thousands of peaceful protestors and hundreds of opposition political party members. The government anticipates a high level of opposition in Oromia, and signs of dissent are sought out and regularly, sometimes pre-emptively, suppressed. In numerous cases, actual or suspected dissenters have been detained without charge or trial, killed by security services during protests, arrests and in detention."[167]

According to Amnesty international, there is a sweeping repression in the Oromo region of Ethiopia.[167] On December 12, 2015, the German broadcaster Deutsche Welle reported violent protests in the Oromo region of Ethiopia in which more than 20 students were killed. According to the report, the students were protesting against the government's re-zoning plan named 'Addis Ababa Master5 Plan'.

On October 2, 2016, nearly 700 festival goers were massacred at the most sacred and largest event among the Oromo, the Irreecha cultural thanksgiving festival. In just one day, hundreds were killed and many more injured in what will go down in history as one of the darkest days for the Oromo people. Every year, millions of Oromos, the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, gather in Bishoftu for this annual celebration. However this year, the festive mood quickly turned chaotic after Ethiopian security forces responded to peaceful protests by firing tear gas and live bullets at over two million people surrounded by a lake and cliffs.

Notable people

- Abebe Bikila – The first Ethiopian to win a gold medal in the Olympics[168]

- Sheikh Muhammad Rashad - The Father of qubee - developed the current Oromo alphabet

- Jaarraa Abbaa Gadaa - The first leader of Oromo Liberation Army.

- Kenenisa Bekele – Athlete

- Abiy Ahmed Ali – Prime Minister of Ethiopia

- Ali Birra – Singer, poet, and Oromo nationalist[169][170][171]

- Sheik Bakri Sapalo – Historian and poet who developed an alphabet for Oromo language [172]

- Derartu Tulu – Athlete[173]

- Fatuma Roba – first African woman[174] to win the Olympic gold medal in a marathon

- Ras Gobana Dacche – Top general in Shewan Kingdom.

- HabteGiyorgis Dinagde Botera – War minister and first person to take the prime-minister position.

- Sultan Aba Jifar – Governor of Jimma until 1932

- Balcha Aba Nefso – Governor of Sidamo and Harar provinces. He fought in the first Italo-Ethiopian war and died while fighting the second one.

- Girma Wolde-Giorgis – Former President of Ethiopia[175]

- Mulatu Teshome – President of Ethiopia[175][176]

- Tadesse Birru – Father of Oromo nationalism

- Elemo Qiltu – First commander of the Oromo Liberation Army

- Tsegaye Gabre-Medhin – Poet Laureate of Ethiopia

- Dr. Haile Fida Kuma– Leader of All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement

- Tirunesh Dibaba – Athlete

- Malik Ambar – Statesman and warrior in India, where he was brought as a slave in the 16th century[177]

- Feyisa Lilesa - Olympic silver medal winning marathon runner

- Tirunesh Dibaba - Athlete

- Almaz Ayana - Athlete

- Onesimos Nesib - Translated the Bible into the Oromo language in 1899

See also

References

- ↑ Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia. "Table 2.2 Percentage Distribution of Major Ethnic Groups: 2007" (PDF). Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results. United Nations Population Fund. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Census: Ethnic Affiliation". knbs.or.ke. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

161,399 Borana, 66,275 Orma

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics 2014, The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS, 30 November 2016, Archived 17 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 James B. Minahan (2016). Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 319–320. ISBN 978-1-61069-954-9.

- ↑ Joireman, Sandra F. (1997). Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development. Universal-Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 1581120001.

- 1 2 Ethiopia: People & Society Archived 23 February 2011 at Wikiwix, CIA Factbook (2016)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tesema Ta'a (2006). The Political Economy of an African Society in Transformation: the Case of Macca Oromo (Ethiopia). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 17–19 with footnotes. ISBN 978-3-447-05419-5.

- 1 2 Mohammed Hassen (2015). The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700. Boydell & Brewer (Originally: Cambridge University Press). pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- ↑ Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. 35–41. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

- ↑ "Gada system, an indigenous democratic socio-political system of the Oromo - intangible heritage - Culture Sector - UNESCO". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- 1 2 Harold G. Marcus A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press (1994) pp. 55 Google Books

- ↑ John Ralph Willis (2005). Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two: The Servile Estate. Routledge. pp. 122–127, 129–134, 137. ISBN 978-1-135-78017-3.

- 1 2 3 4 John Ralph Willis (2005). Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two: The Servile Estate. Routledge. pp. 128–134. ISBN 978-1-135-78016-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Ira M. Lapidus (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 483. ISBN 978-1-139-99150-6.

- 1 2 AJISS. Association of Muslim Social Scientists, International Institute of Islāmic Thought. 26: 87. 2009 https://www.google.com/books?id=tYtAAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 19 June 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Richard Pankhurst (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. pp. 279–280. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- 1 2 3 Mohammed Hassen, Conquest, Tyranny, and Ethnocide against the Oromo: A Historical Assessment of Human Rights Conditions in Ethiopia, ca. 1880s–2002 , Northeast African Studies Volume 9, Number 3, 2002 (New Series)

- ↑ Arne Perras (2004). Carl Peters and German Imperialism 1856-1918: A Political Biography. Oxford University Press. pp. 154–157. ISBN 978-0-19-926510-7.

- 1 2 Ta'a, Tesema (2006). The Political Economy of an African Society in Transformation. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-447-05419-5. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- 1 2 Ernesta Cerulli (1956), Peoples of South-west Ethiopia and its Borderland, International African Institute, Routledge, ISBN 978-1138234109, Chapter: History & Traditions of Origin

- 1 2 Lewis, Herbert S. (1966). "The Origins of the Galla and Somali". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 7 (1): 27–46. doi:10.1017/s0021853700006058.

- ↑ Gikes, Patrick (2002). "Wars in the Horn of Africa and the dismantling of the Somali State". African Studies. University of Lisbon. 2: 89–102. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ "Frankfurter afrikanistische Blätter". Frankfurt University Library (1). 1989. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- 1 2 Mohammed Hassen (2015). The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700. Boydell & Brewer (Originally: Cambridge University Press). pp. 66–68, 85, 104–106. ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- 1 2 3 Juxon Barton (September 1924), The Origins of the Oromo and Somali Tribes, The Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society, No. 19, pages 6-7

- 1 2 International African Institute Ethnographic Survey of Africa, Volume 5, Issue 2 (1969) pp. 11

- ↑ CF Beckingham and George Huntingford (1967). Some records of Ethiopia, 1593-1646, being extracts from the history of High Ethiopia or Abassia (Series: Oromo Peuple d'Afrique). Kraus Nendeln, Liechtenstein. pp. 1–7. OCLC 195934.

- ↑ Claude Sumner Ethiopian Philosophy: The treatise of Zärʼa Yaʻe̳quo and of Wäldä Ḥe̳ywåt Addis Ababa University, (1976) pp. 149 footnote 312, Quote: "D'Abbadie claimed that the name Galla was explained to him as derived from a war cry, and used by the Gallas of themselves at war."

- ↑ Oromo Archived 30 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Merriam-Webster (2014). Quote: "Origin and Etymology of Oromo, (western dialect) oromoo, a self-designation, First known use: 1893."

- ↑ Susanne Epple (2014). Creating and Crossing Boundaries in Ethiopia: Dynamics of Social Categorization and Differentiation. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 193–194, 205–206 with footnotes 23–26. ISBN 978-3-643-90534-5.

- ↑ Asafa Jalata (1993), "Sociocultural origins of the Oromo national movement in Ethiopia", Journal of Political and Military Sociology, Volume 21, Number 2 (January), pages 275-276. Quote: "Ethiopianists distorted Oromo history by calling the Oromo "Galla" and degrading them as savage, pagan, slave, uncivilized (...)".

- ↑ Garland Hampton Cannon; Alan S. Kaye (1994). The Arabic Contributions to the English Language. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 60. ISBN 978-3-447-03491-3. Quote: "In Somalia, galla pejoratively named the Oromo language, a white European, or any heathen, i.e. non-Muslim; toubab is comparable in west and central Africa."

- ↑ Asafa Jalata (2002). Fighting Against the Injustice of the State and Globalization: Comparing the African American and Oromo Movements. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 95, 99–100. ISBN 978-0-312-29907-1.

- ↑ Didier Morin (2005). Walter Raunig and Steffen Wenig, ed. Afrikas Horn. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 432. ISBN 978-3-447-05175-0.

- ↑ Kjetil Tronvoll, Tobias Hagmann Contested Power in Ethiopia: Traditional Authorities and Multi-Party Elections BRILL, (2011) pp. 32

- ↑ Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism Algora Publishing, (2005) pp. 275

- ↑ Brian L. Fargher (1996). The Origins of the New Churches Movement in Southern Ethiopia: 1927 - 1944. BRILL Academic. pp. 272 footnote 82. ISBN 90-04-10661-8.

- ↑ Mohammed Hassen (2015). The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 3–4 with footnotes 14–18. ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- ↑ Abbas Gnamo (2014). Conquest and Resistance in the Ethiopian Empire, 1880 - 1974: The Case of the Arsi Oromo. BRILL Academic. pp. 59–81. ISBN 978-90-04-26548-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Alessandro Triulzi (1996). Paul Trevor William Baxter, Jan Hultin and Alessandro Triulzi., ed. Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 251–256. ISBN 9789171063793.

- ↑ Mekuria Bulcha, Jan Hultin (1996). Paul Trevor William Baxter, Jan Hultin and Alessandro Triulzi., ed. Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 55–56, 55–56, 85–90. ISBN 9789171063793.

- 1 2 3 Erwin Fahlbusch (1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

- 1 2 Tesema Ta'a (2006). The Political Economy of an African Society in Transformation: the Case of Macca Oromo (Ethiopia). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-3-447-05419-5.

- ↑ Mohammed Hassen (2015). The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- ↑ "

- ↑ "Oromo Archived 30 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine." in the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.

- ↑ Mohammed Hassen (2015). The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 222–225. ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- 1 2 Donald N. Levine (2000). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. 78–89. ISBN 978-0-226-47561-5.

- 1 2 3 W.A. Degu, "Chapter 7 Political Development in the Pre-colonial Horn of Africa" Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine., The State, the Crisis of State Institutions and Refugee Migration in the Horn of Africa: The Cases of Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia, Thela Thesis (Amsterdam, 2002), page 142

- 1 2 Richard Pankhurst (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. pp. 281–283. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- ↑ Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst (2013). Kevin Shillington, ed. Encyclopedia of African History. Routledge. pp. 1182–1183. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2.

- ↑ "Oromo and Amhara rule in Ethiopia" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Paul Trevor William Baxter, Jan Hultin, Alessandro Triulzi. Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries'. Nordic Africa Institute (1996) pp. 123–124

- ↑ Aṣma Giyorgis, Bairu Tafla Aṣma Giyorgis and His Work: History of the Gāllā and the Kingdom of Šawā. Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH (1987) pp. 439 Google Books

- ↑ Günther Schlee Identities on the Move: Clanship and Pastoralism in Northern Kenya. Manchester University Press (1989) pp. 38–40 Google Books

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rudolph T. Ware (2011). David Eltis; Stanley L. Engerman, eds. The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420–AD 1804. Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–74. ISBN 978-1-316-18435-6.

- ↑ Paul E. Lovejoy (2011). Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-139-50277-1.

- ↑ Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. Praeger. pp. 57–61.

- ↑ Lipsky, George Arthur (1962). Ethiopia: Its People, Its Society, Its Culture, Volume 9. Hraf Press. pp. 36, 50, 61. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Paul E. Lovejoy (2011). Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1-139-50277-1.

- ↑ Benjamin Reilly (2015). Slavery, Agriculture, and Malaria in the Arabian Peninsula. Ohio University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-8214-4540-2.

- ↑ Ehud R. Toledano (2014). The Ottoman Slave Trade and Its Suppression. Princeton University Press. pp. 15–27. ISBN 978-1-4008-5723-4.

- ↑ Bernard Lewis (1992). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Oxford University Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-19-505326-5.

- ↑ John Ralph Willis (2005). Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two: The Servile Estate. Routledge. pp. 122–127, 137. ISBN 978-1-135-78017-3.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century, 1997. p. 284, 423

- 1 2 J. Bermudez The Portuguese Expedition to Abyssinia in 1541–1543 as Narrated by Castanhoso, 1543. p. 229.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century - Google Books": , 1997. p. 325.

- ↑ Ehud R. Toledano (2014). The Ottoman Slave Trade and Its Suppression: 1840-1890. Princeton University Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-1-4008-5723-4. Quote: "The first section of this [slave] trade was in the hands of Ethiopian dealers who drove the slaves from the southern and southwestern Galla, Sidama and Gurage principalities to the central Amhara provinces. (...) the average Afar caravan consisted of thirty to fifty merchants and about two hundred slaves."

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, p. 414.

- ↑ "Ras Gobena victory against Gurage militia" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Donald Levine, Greater Ethiopia, the Evolution of a multicultural society (University of Chicago Press: 1974)

- ↑ John Ralph Willis (2005). Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two: The Servile Estate. Routledge. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-135-78017-3.

- ↑ E. R. Toledano (2014). The Ottoman Slave Trade and Its Suppression: 1840-1890. Princeton University Press. pp. 15–16, 21–22, 24–31. ISBN 978-1-4008-5723-4.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst (1976), stable/40758604 The Beginnings of Oromo Studies in Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell'Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, Anno 31, No. 2 (GIUGNO 1976), pp. 171-172]

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abdussamad Ahmad (2013). William Gervase Clarence-Smith, ed. The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge. pp. 93–99. ISBN 978-1-135-18214-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Timothy Fernyhough (2013). William Gervase Clarence-Smith, ed. The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge. pp. 103–106, 108–112, see Table 2 e.g. ISBN 978-1-135-18214-4.

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 108 and 93 Google Books

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 106-115 Google Books

- 1 2 3 4 Harold G. Marcus A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press (1994) pp. 55 Google Books

- ↑ Donald N. Levine 2014, p. 156, According to Levine, this was a large part of the increased slave trade in the first half of the nineteenth century..

- ↑ G.W.B. Huntingford (1969). The Galla of Ethiopia, Ethnographic Survey of Africa. International African Institute (Republished: Routledge). pp. 31, 126. ISBN 978-1138232174.

- ↑ Harold G. Marcus (1994). A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-520-08121-5.

- ↑ Gwyn Campbell; Suzanne Miers; Joseph Calder Miller (2007). Women and Slavery: Africa, the Indian Ocean world, and the medieval north Atlantic. Ohio University Press. pp. 215–228. ISBN 978-0-8214-1723-2.

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 93 Google Books

- ↑ Declich, Francesca (2009). "Dynamics of Intermingling Gender and Slavery in Somalia at the Turn of the Twentieth Century". Northeast African Studies. Johns Hopkins University Press. 10 (3): 46, 45–69. doi:10.1353/nas.0.0024.

- ↑ Declich, Francesca (2009). "Dynamics of Intermingling Gender and Slavery in Somalia at the Turn of the Twentieth Century". Northeast African Studies. Johns Hopkins University Press. 10 (3): 54, 62–64. doi:10.1353/nas.0.0024. ; Note: Declich mentions that Oromo were not only one enslaved and traded in Somali markets, Bantu and Swahili origin women as well were traded as sex slaves and domestic servile work but they attracted lower prices.

- ↑ R. W. Beachey The slave trade of eastern Africa, Volume 1. Barnes & Noble Books-Imports (1976) pp. 149-150, 158-159

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 106 Google Books

- ↑ International African Institute Ethnographic Survey of Africa, Volume 5, Issue 2. (1969) pp. 31 Google Books

- ↑ Donald N. Levine 2014, pp. 85, 136.

- ↑ Donald N. Levine 2014, pp. 85-86.

- ↑ Donald N. Levine 2014, p. 85.

- ↑ "Union of Amhara and Oromo in royal families". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ "Oromo in Ethiopian leadership". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Atsuko Karin Matsuoka; John Sorenson (2001). Ghosts and Shadows: Construction of Identity and Community in an African Diaspora. University of Toronto Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-8020-8331-9.

- ↑ Mekuria Bulcha, Genocidal violence in the making of nation and state in Ethiopia, African Sociological Review

- ↑ Alemayehu Kumsa, Power and Powerlessness in Contemporary Ethiopia, Charles University in Prague

- ↑ Haberland, "Amharic Manuscript", pp. 241f

- ↑ Alemayehu Kumsa, Power and Powerlessness in Contemporary Ethiopia, Charles University in Prague pp. 1122

- ↑ Eshete Gemeda, African Egalitarian Values and Indigenous Genres: A Comparative Approach to the Functional and Contextual Studies of Oromo National Literature in a Contemporary Perspective, pp 186;

A. K. Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898, translated by Richard Seltzer, 2000 pp. 68 - ↑ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 69.

- ↑ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 68.

- ↑ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 11.

- ↑ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 12.

- ↑ Peter Gill Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid Oxford University Press, 2010 Google Books

- ↑ Bulcha, Mekuria (1988). Flight and Integration. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 39–40. ISBN 9789171062796. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Ahmad, Akbar (2013-02-27). The Thistle and the Drone. Brookings Institution Press. p. 233. ISBN 0815723792. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Mengisteab, Kidane (1999). State Building and Democratization in Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 240. ISBN 9780275963538. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism. Algora Publishing (2005) pp. 274-275 Google Books

- ↑ "Ethiopian Oroo nobility". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ Fikre Tolossa Nobles of Oromo Descent Who Ruled Ethiopia Archived 3 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Ethiopian Review (1992)

- ↑ Harold D. Nelson, Irving Kaplan Ethiopia, a Country Study, Volume 28. American University, Foreign Area Studies (1981) pp. 14 Google Books

- ↑ Trevor, Paul (1996). Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Isntitute. p. 32. ISBN 9789171063793. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 25 Google Books

- ↑ Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 156 & 157 Google Books

- ↑ Kjetil Tronvoll, Ethiopia, a new start?, (Minority Rights Group: 2000)

- ↑ Peter Woodward, Conflict and peace in the Horn of Africa: federalism and its alternatives, (Dartmouth Pub. Co.: 1994), p.29.

- ↑ Haile Selassie I, My Life and Ethiopia's Progress: The Autobiography of Emperor Haile Sellassie I, translated from Amharic by Edward Ullendorff. (New York: Frontline Books, 1999), vol. 1 p. 13

- ↑ Paul Trevor William Baxter; Jan Hultin; Alessandro Triulzi (1996). Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 978-91-7106-379-3. :71–75

- 1 2 Oromo people Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "Oromo, Borana-Arsi-Guji". ethnologue.com). Archived from the original on 16 January 2009.

- ↑ Aguilar, Mario. "The Eagle as Messenger, Pilgrim and Voice: Divinatory Processes among the Waso Boorana of Kenya". Journal of Religion in Africa, Vol. 26, Fasc. 1 (Feb., 1996), pp. 56–72. JSTOR 1581894.

- 1 2 "Oromo - A macrolanguage of Ethiopia". Ethnorm. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ↑ Asafa Jalata (1998) Oromo Nationalism and the Ethiopian Discourse: The Search for Freedom and Democracy p. 195.

- ↑ "Oromo, West Central". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ↑ R. J. Hayward and Mohammed Hassan (1981). "The Oromo Orthography of Shaykh Bakri Saṗalō". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. p. 44.3, 550–566. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ "The Oromo Orthography of Shaykh Bakri Sapalo". Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ↑ Erwin Fahlbusch (1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

- ↑ Census (PDF), Ethiopia, 2007, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2016

- 1 2 3 Tesema Ta'a (2006). The Political Economy of an African Society in Transformation: the Case of Macca Oromo (Ethiopia). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-3-447-05419-5.

- ↑ Paul Trevor William Baxter; Jan Hultin; Alessandro Triulzi (1996). Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 252–253. ISBN 978-91-7106-379-3.

gadaa government was a preclass institution based on democratic principles even though it did exclude caste groups such as smiths and tanners, and women (...)

- ↑ Tesema Ta'a (2006). The Political Economy of an African Society in Transformation: the Case of Macca Oromo (Ethiopia). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-3-447-05419-5.

- ↑ J. Abbink (1985), Review: Oromo Religion. Myths and Rites of the Western Oromo of Ethiopia by Lambert Bartels, Journal: Anthropos, Bd. 80, H. 1./3. (1985), pages 285-287

- ↑

- 1 2 Herbert S. Lewis (1965). Jimma Abba Jifar, an Oromo Monarchy: Ethiopia, 1830-1932. The Red Sea Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-56902-089-0.

- 1 2 Eike Haberland (1993), Hierarchie und Kaste : zur Geschichte und politischen Struktur der Dizi in Südwest-Äthiopien, Stuttgart : Steiner, ISBN 978-3515055925 (in German), pages 105-106, 117-119

- ↑ Quirin, James (1979). "The Process of Caste Formation in Ethiopia: A Study of the Beta Israel (Felasha), 1270-1868". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. Boston University African Studies Center. 12 (2): 235. doi:10.2307/218834. JSTOR 218834.

;

Haji, Abbas (1997). "Pouvoir de bénir et de maudire : cosmologie et organisation sociale des Oromo-Arsi" (PDF). Cahiers d'études africaines (in French). PERSEE. 37 (146): 290, 297, context: 289–318. doi:10.3406/cea.1997.3515. Retrieved 2016-11-18. - ↑ Asafa Jalata (2010), Oromo Peoplehood: Historical and Cultural Overview Archived 19 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Sociology Publications and Other Works, University of Tennessee Press, page 12, see "Modes of Livelihood" section

- ↑ Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

- ↑ Ernesta Cerulli (1922). The Folk-Literature of the Oromo of Southern Abyssinia, Harvard African studies, v. 3. Istituto Orientale di Napoli, Harvard University Press. pp. 341–355.

- ↑ William Gervase Clarence-Smith (2013). The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge. pp. 93–97. ISBN 978-1-135-18214-4.

- ↑ Ronald Segal (2002). Islam's Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora. MacMillan. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-374-52797-6.

- ↑ Said S. Samatar (1992). In the Shadow of Conquest: Islam in Colonial Northeast Africa. The Red Sea Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-932415-70-7.

- ↑ Ruggles, Clive (2006). Ancient Astronomy: An Encyclopedia of Cosmologies and Myth. ABC-Clio. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-1851094776. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Afe Adogame (2016). The Public Face of African New Religious Movements in Diaspora. Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-317-01863-6.

- ↑ Clive L. N. Ruggles (2005). Ancient Astronomy: An Encyclopedia of Cosmologies and Myth. ABC-CLIO. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-85109-477-6.

- ↑ Doyle, Laurance R. The Borana Calendar REINTERPRETED. Current Anthropology. Physics and Astronomy Department, University of California, Santa Cruz, at NASA Ames Research Center, Space Sciences Division, M.S., retrieved: 7 April 2010.

- 1 2 Gemetchu Megerssa (1996). Paul Trevor William Baxter; et al., eds. Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 92–96. ISBN 978-91-7106-379-3.

- ↑ Terje Østebø (2011). Localising Salafism: Religious Change Among Oromo Muslims in Bale, Ethiopia. BRILL Academic. pp. 292–293 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-18478-3.

Orumumma can best be translated as Oromoness, signifying belonging to the Oromo people. (...) neologism introduced by Mekuria Bulcha (1996) and Gemetchu Megersa (1996). (...) Whether this was a result of the larger ethno-nationalist discourse is yet another question.

- ↑ Terje Østebø (2011). Localising Salafism: Religious Change Among Oromo Muslims in Bale, Ethiopia. BRILL Academic. pp. 301–302 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-18478-3.

- ↑ Günther Schlee (2002). Imagined Differences: Hatred and the Construction of Identity. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 142–146. ISBN 978-3-8258-3956-7.

- ↑ "HUMAN RIGHTS IN ETHIOPIA : THROUGH THE EYES OF THE OROMO DIASPORA" (PDF). Theadvocatesforhumanrights.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ↑ "Human rights abuses under EPRDF" (PDF). Lib.ohchr.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ↑ "Ethiopian forces 'kill 140 Oromo protesters'". 8 January 2015. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Unrest in Ethiopia: Grumbling and rumbling: Months of protests are rattling a fragile federation". The Economist. 26 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "Migrations profoundly affected the Oromo unity". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Raya Oromos inside the Weyane revolt of Tigray" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia: 1855–1991, 2nd edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), pp. 261f.

- ↑ "Govt. continues rejecting license for Jimma Times Afaan Oromoo newspaper". Ethioguardian.com. 9 May 2008. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Ethiopia's "government" attacks Macha-Tulama, Jimma Times media & Oromo opposition party". Nazret.com. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ CJFE award nominee Archived 25 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- ↑ "Ethiopia's Largest Ethnicity Group Deprived of Linguistic and Cultural Sensitive Media Outlets". Rap21.org. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "OFDM Press Release: The Massacre of May, 2008". Jimmatimes.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Ethiopia: 'Because I am Oromo': Sweeping repression in the Oromia region of Ethiopia". Amnesty.org. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ↑ "Abebe Bikila: barefoot to Olympic gold". Olympic.org. 7 February 2017. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ↑ "Ethiopia: Ali Birra not quitting music". Jimma Times. Jimma. 12 August 2009. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ali Birra, Great Oromo Music". Ethiopiques. Buda Musique. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ali Birra, 50th Anniversary". SiiTube. SiiTube. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ Mohammed, Abdulsemed (13 June 2013). "SEENAA BARREEFAMA AFAAN OROMOOTIIFI SHOORA DR. SHEEK MAHAMMAD RASHAAD" [HISTORY OF OROMO WRITING and the Contribution of Dr. Mohammed Reshad] (in Oromo). Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "Derartu TULU". Olympic.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ Tanser, Toby (19 April 2008). "Fatuma Roba: A Twisted Path to Living Legend". Runnersworld.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Ethiopia Elects Dr. Mulatu Teshome as president". Awramba Times. 7 October 2013. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ethiopia parliament elects Mulatu Teshome as new president". Rappler. AFP. 7 October 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ↑ Deqi-Arawit. "History Lesson: Malik Ambar". Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

Further reading

- Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

- Tsega Etefa, Integration and Peace in East Africa: A History of the Oromo Nation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. ISBN 978-0-230-11774-7

- Mohammed Hassan, The Oromo of Ethiopia, A History 1570–1860. Trenton: Red Sea Press, 1994. ISBN 0-932415-94-6

- Herbert S. Lewis. A Galla Monarchy: Jimma Abba Jifar, Ethiopia 1830–1932. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1965.

- "RIC Query – Ethiopia". INS Resource Information Center. Archived from the original on 1 November 2005. Retrieved 8 October 2005.

- Temesgen M. Erena, Oromia: 'Civilisation, Colonisation And Underdevelopment, Oromia Quarterly, No.1, July 2002, ISSN 1460-1346.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oromo people. |

- ↑ , Ethiopian Government Portal