Amhara people

| አማራ (Amharic) | |

|---|---|

The Amhara ethnic flag[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 19,867,817 [2] | |

| 195,260 [3] | |

| 115,500 [4] | |

| 18,020 [5][6][7] | |

| 8,620 [8] | |

| 5,600 [9] | |

| 4,515 [10] | |

| Languages | |

| Amharic | |

| Religion | |

|

Majority: Christianity (Ethiopian Orthodox) Minorities: Islam (Sunni), Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Amharas (Amharic: አማራ, Āmara;[12] Ge'ez: አምሐራ, ʾÄməḥära), also known as Abyssinians,[13][14] are an ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the northern and central highlands of Ethiopia, particularly the Amhara Region. According to the 2007 national census, they numbered 19,867,817 individuals, comprising 26.9% of Ethiopia's population.[2] They are also found within the Ethiopian expatriate community, particularly in North America.[3] The Amharas claim to originate from Solomon and primarily adhere to the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[15] They speak Amharic, an Afro-Asiatic language of the Semitic branch, a member of the Ethiosemitic group, which serves as the official language of Ethiopia.

Etymology

The present name for the Amharic language and its speakers comes from the medieval province of Amhara. The latter enclave was located around Lake Tana at the headwaters of the Blue Nile, and included a slightly larger area than Ethiopia's present-day Amhara Region.

The further derivation of the name is debated. Some trace it to amari ("pleasing; beautiful; gracious") or mehare ("gracious"). The Ethiopian historian Getachew Mekonnen Hasen traces it to an ethnic name related to the Himyarites of ancient Yemen.[16] Still others say that it derives from Ge'ez ዓም (ʿam, "people") and ሓራ (h.ara, "free" or "soldier"), although this has been dismissed by scholars such as Donald Levine as a folk etymology.[17]

History

The Amharas have historically inhabited the central and western parts of Ethiopia, and have been the politically dominant ethnic group of this region.[18] Their origins is near modern day Werehimenu, Wollo province, a place that was known as Bete Amhara in the past.[19] The settlement of Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations in Greater Ethiopia may have occurred between the 5th and 3rd millennium BCE. At this time, dark-skinned Caucasoid or Afro-Mediterranean peoples, consisting of Cushitic and Omotic speakers from the eastern Sahara and Semitic speakers from South Arabia, settled the area.[20] The ancient Semitic-speaking Himyarites, who moved from Yemen into northern Ethiopia sometime before 500 BCE, are believed to have been ancestral to the Amhara. They intermarried with the earlier Cushitic-speaking settlers, and gradually spread into the region the Amhara presently inhabit.[18][19] The Amhara are currently one of the two largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia, along with the Oromo.[18][19] They are sometimes referred to as "Abyssinians".[18].[21][22]

The region now known as "Amhara" in the feudal era was composed of several provinces with greater or less autonomy, which included Gondar, Gojjam, Wollo (Bete Amhara) and Shewa.[23] The traditional homeland of the Amharas is the central highland plateau of Ethiopia. For over two thousand years they have inhabited this region. Walled by high mountains and cleaved by great gorges, the ancient realm of Abyssinia has been relatively isolated from the influences of the rest of the world. The region is situated at altitudes ranging from roughly 7,000 to 14,000 feet (2,100 to 4,300 meters), and at a 9 o to 14 o latitude north of the equator. The rich volcanic soil combines with a generous rainfall and cool, brisk climate to offer the Amhara a stable agricultural and pastoral existence.

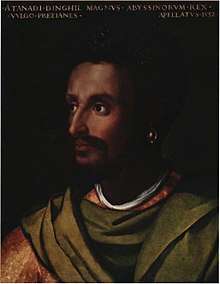

Following the end of the ruling Agaw Zagwe dynasty, the Solomonic dynasty governed the Ethiopian Empire for many centuries from the 1270 AD onwards. In the early 15th century, Abyssinia sought to make diplomatic contact with European kingdoms for the first time since Aksumite times. A letter from King Henry IV of England to the Emperor of Abyssinia survives.[24] In 1428, the Emperor Yeshaq sent two emissaries to Alfonso V of Aragon, who sent return emissaries who failed to complete the return trip.[25] The first continuous relations with a European country began in 1508 with Portugal under Emperor Lebna Dengel, who had just inherited the throne from his father.[26]

This proved to be an important development, for when the Empire was subjected to the attacks of the Adal Sultanate General and Imam, Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (called "Grañ", or "the Left-handed"), Portugal assisted the Ethiopian emperor by sending weapons and four hundred men, who helped his son Gelawdewos defeat Ahmad and re-establish his rule.[27] This Ethiopian–Adal War was also one of the first proxy wars in the region as the Ottoman Empire and Portugal took sides in the conflict.

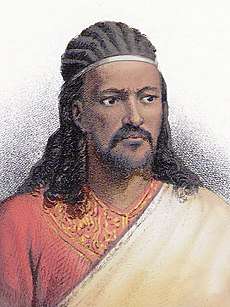

The Amhara have contributed many rulers over the centuries, including Haile Selassie.[28] Haile Selassie's mother was paternally of Oromo descent and maternally of Gurage heritage, while his father was paternally Oromo and maternally Amhara. He consequently would have been considered Oromo in a patrilineal society, and would have been viewed as Gurage in a matrilineal one. However, in the main, Haile Selassie was regarded as Amhara, his paternal grandmother's royal lineage, through which he was able to ascend to the Imperial throne.[29]

Slavery

According to Donald Levine, slavery was widespread in Greater Ethiopia until the 1930s. More powerful groups could consign to slavery weaker members of other communities or even individuals from their own tribe. Since the Amhara and Tigreans were prohibited from enslaving other Christians, they held slaves from many non-Christian groups.[30][note 1] The medieval Adal Sultanate seized slaves during jihad expeditions in Christian outposts in the old provinces of Amhara, Shäwa, Fatagar,[34][35] and Dawaro.[36] Many of the slaves seized by Adal were assimilated, others exported or gifted to rulers of Arabia in exchange for military support.[34]

The Amhara, as the ruling people, enslaved other ethnic groups such as the Oromo people (historically referred to as Galla).[37][38][30] The Amhara were also occasionally enslaved by the Afar,[30] and sometimes Amhara boys and girls were kidnapped by slave raiders from northern Ethiopia and then sold.[39] The central Amhara provinces were a part of major Afar slave caravan trade routes from the southern and southwestern regions to the northern and eastern Ethiopia.[40] According to Terence Walz and Kenneth M. Cuno, it is not uncommon to find references to Abyssinian slaves in Ottoman-era court records, but such mentions become rare by the 19th century. They indicate that it is improbable that Amhara were enslaved during the rule of Ali Mubarak because they governed the Abyssinian highlands and also frequently raided for slaves in other areas.[41]

According to Gustav Arén, Ethiopian law did not prohibit slave-holding, but did forbid the enslavement of Christians.[42] As such, George Arthur Lipsky indicates that the Amhara resisted converting the non-Christian ethnic groups to Christianity, because they could not thereafter be kept or sold as slaves.[43] John Ralph Willis states that, with few exceptions, slave merchants typically avoided purchasing Christian Amhara, Tigrean or Muslim slaves.[44]

Social stratification

Within traditional Amharic society and that of other local Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations, there were four basic strata. According to the Ethiopianist Donald Levine, these consisted of high-ranking clans, low-ranking clans, caste groups (artisans), and slaves.[45][46] Slaves were at the bottom of the hierarchy, and were primarily drawn from the pagan Nilotic Shanqella groups. Also known as the barya (meaning "slave" in Amharic), they were captured during slave raids in Ethiopia's southern hinterland. War captives were another source of slaves, but the perception, treatment and duties of these prisoners was markedly different.[47] According to Donald Levine, the widespread slavery in Greater Ethiopia formally ended in the 1930s, but former slaves, their offspring, and de facto slaves continued to hold similar positions in the social hierarchy.[30]

The separate, Amhara caste system, ranked higher than slaves, consisted of: (1) endogamy, (2) hierarchical status, (3) restraints on commensality, (4) pollution concepts, (5) each caste has had a traditional occupation, and (6) inherited caste membership.[45][48] Scholars accept that there has been a rigid, endogamous and occupationally closed social stratification among Amhara and other Afro-Asiatic-speaking Ethiopian ethnic groups. However, some label it as an economically closed, endogamous class system or as occupational minorities,[49][50] whereas others such as the historian David Todd assert that this system can be unequivocally labelled as caste-based.[51][52][53]

Language

The Amhara speak Amharic (also known as Amarigna or Amarinya) as a mother tongue. It is spoken by 29.3% of the Ethiopian population.[54] It belongs to the Semitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family.[55]

According to Donald Levine, the Afro-Asiatic (Hamito-Semitic) language family likely arose in either the eastern Sahara or southwestern Ethiopia. Early Afro-Asiatic populations speaking proto-Semitic, proto-Cushitic and proto-Omotic languages would have diverged by the fourth or fifth millennium BC. Shortly afterwards, the proto-Cushitic and proto-Omotic groups would have settled in the Ethiopian highlands, with the proto-Semitic speakers crossing the Sinai Peninsula into Asia Minor. A later return movement of peoples from South Arabia would have introduced the Semitic languages to Ethiopia.[20] Based on archaeological evidence, the presence of Semitic speakers in the territory date to sometime before 500 BC.[19] Linguistic analysis suggests the presence of Semitic languages in Ethiopia as early as 2000 BC. Levine indicates that by the end of that millennium, the core inhabitants of Greater Ethiopia would have consisted of swarthy Caucasoid ("Afro-Mediterranean") agropastoralists speaking Afro-Asiatic languages of the Semitic, Cushitic and Omotic branches.[20]

According to Robert Fay, the ancient Semitic speakers from Yemen were Himyarites and they settled in the Aksum area in northern Ethiopia. There, they intermarried with native speakers of Agaw and other Cushitic languages, and gradually spread southwards into the modern Amhara homeland. Their descendants, the early Amhara, spoke Ge'ez, the official language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[56]

Amharic is the working language of the federal authorities of Ethiopia government. It was for some time also the language of primary school instruction, but has been replaced in many areas by regional languages such as Oromifa and Tigrinya. Nevertheless, Amharic is still widely used as the working language of Amhara Region, Benishangul-Gumuz Region, Gambela Region and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region.[57] The Amharic language is transcribed using the Ethiopic or Ge'ez script (Fidäl), an abugida. The Amharic language is the official language of Ethiopia.

Most of the Ethiopian Jewish communities in Ethiopia and Israel speak Amharic.[4] Many in the popular Rastafari movement learn Amharic as a second language, as they consider it to be a sacred language.[58]

Religion

The predominant religion of the Amhara for centuries has been Christianity, with the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church playing a central role in the culture of the country. According to the 2007 census, 82.5% of the population of the Amhara Region (which is 91.2% Amhara) were Ethiopian Orthodox; 17.2% were Muslim, and 0.2% were Protestant ("P'ent'ay").[59] The Ethiopian Orthodox Church maintains close links with the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. Easter and Epiphany are the most important celebrations, marked with services, feasting and dancing. There are also many feast days throughout the year, when only vegetables or fish may be eaten.

Marriages are often arranged, with men marrying in their late teens or early twenties.[60] Traditionally, girls were married as young as 14, but in the 20th century, the minimum age was raised to 18, and this was enforced by the Imperial government. After a church wedding, divorce is frowned upon.[60] Each family hosts a separate wedding feast after the wedding.

Upon childbirth, a priest will visit the family to bless the infant. The mother and child remain in the house for 40 days after birth for physical and emotional strength. The infant will be taken to the church for baptism at 40 days (for boys) or 80 days (for girls).[61]

Culture

Art

Amhara art is typified by religious paintings. One of the notable features of these is the large eyes of the subjects, who are usually biblical figures. It is usually oil on canvas or hide, some surviving from the Middle Ages. The Amhara art includes weaved products embellished with embroidery. Works in gold and silver exist in the form of filigree jewelry and religious emblems.

Agriculture

About 90% of the Amhara are rural and make their living through farming, mostly in the Ethiopian highlands. Prior to the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution, absentee landlords maintained strict control over sharecropping tenants, who often accumulated crippling debt. After 1974, the landlords were replaced by local government officials, who play a similar role.

Barley, corn, millet, wheat, sorghum, and teff, along with beans, peppers, chickpeas, and other vegetables, are the most important crops. In the highlands one crop per year is normal, while in the lowlands two are possible. Cattle, sheep, and goats are also raised.

Kinship and marriage

The Amhara culture recognizes kinship, but unlike other ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa region, it has a relatively lesser role. Household relationships are primary, and the major economic, political and cultural functions are not based on kin relationships among the Amharas. Rather abilities of the individual matter. For example, states Donald Levine, the influence of clergy among the Amhara has been based on "ritual purity, doctrinal knowledge, ability to perform miracles and capacity to provide moral guidance".[62] The social relationships in the Amhara culture are predominantly based on hierarchical patterns and individualistic associations.[63]

Family and kin relatives are often involved in arranging semanya (eighty bond marriage, also called kal kidan), which has been most common and allows divorce.[64] Other forms of marriage include qurban, which is solemnized in church, where divorce is forbidden, and usually observed among the orthodox priests.[65] A third form of marriage in Amhara culture has been damoz, which is considered of low status. The damoz marriage is temporary, a man pays the woman to be a temporary wife, typically for a month or two, by an oral contract.[65][66] Patrilineal descent is the norm.[65] While the wife had no inheritance rights, in case a child was conceived during the temporary damoz marriage, the child could make a claim a part of the father's property.[66][67]

Cuisine

The Amharas' cuisine consists of various vegetable or meat side dishes and entrées, usually a wat, or thick stew, served atop injera, a large sourdough flatbread made of teff flour. Kitfo being originated from Gurage is one of the widely accepted and favorite food in Amhara.

They do not eat pork or shellfish of any kind for religious reasons. It is also a common cultural practice of Amhara to eat from the same dish in the center of the table with a group of people.

Claims Amhara identity to be non-existent

Up until the last quarter of the 20th century, "Amhara" was only used (in the form amariñña) to refer to Amharic, the language, or the medieval province located in Wollo (modern Amhara Region). Still today, most people labeled by outsiders as "Amhara", refer to themselves simply as "Ethiopian", or to their province (e.g. Gojjamé from the province Gojjam). According to Ethiopian ethnographer Donald Levine, "Amharic-speaking Shewans consider themselves closer to non-Amharic-speaking Shewans than to Amharic-speakers from distant regions like Gondar."[68] Amharic-speakers tend to be a "supra-ethnic group" composed of "fused stock".[69] Takkele Taddese describes the Amhara as follows:

The Amhara can thus be said to exist in the sense of being a fused stock, a supra-ethnically conscious ethnic Ethiopian serving as the pot in which all the other ethnic groups are supposed to melt. The language, Amharic, serves as the center of this melting process although it is difficult to conceive of a language without the existence of a corresponding distinct ethnic group speaking it as a mother tongue. The Amhara does not exist, however, in the sense of being a distinct ethnic group promoting its own interests and advancing the Herrenvolk philosophy and ideology as has been presented by the elite politicians. The basic principle of those who affirm the existence of the Amhara as a distinct ethnic group, therefore, is that the Amhara should be dislodged from the position of supremacy and each ethnic group should be freed from Amhara domination to have equal status with everybody else. This sense of Amhara existence can be viewed as a myth.[69]

Notable Amharas

- Aklilu Habte-Wold, Prime Minister

- Afewerk Tekle, Honorable Laureate Maitre Artiste

- Haddis Alemayehu, Foreign Minister and Novelist

- Haile Selassie, Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire.

- Menelik II, Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Mesfin Woldemariam, Human rights activist

- Seifu Mikael, diplomat, governor

- Tewodros II, Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Tsegaye Gabre-Medhin, Poet

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations. ABC-CLIO. p. 103. ISBN 9780313076961.

- 1 2 Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia. "Table 2.2 Percentage Distribution of Major Ethnic Groups: 2007" (PDF). Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results. United Nations Population Fund. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- 1 2 United States Census Bureau 2009-2013, Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009-2013, USCB, 30 November 2016, <https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html>.

- 1 2 Amharic-speaking Jews component 85% from Beta Israel; Anbessa Tefera (2007). "Language". Jewish Communities in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries - Ethiopia. Ben-Zvi Institute. p.73 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Statistics Canada, 2011 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-314-XCB2011032

- ↑ Anon, 2016. 2011 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations | Detailed Mother Tongue (232), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population Excluding Institutional Residents of Canada and Forward Sortation Areas, 2011 Census. [online] Www12.statcan.gc.ca. Available at: <http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/tbt-tt/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=103001&PRID=10&PTYPE=101955&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2011&THEME=90&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=> [Accessed 2 Dec. 2016].

- ↑ Immigrant languages in Canada. 2016. Immigrant languages in Canada. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-314-x/98-314-x2011003_2-eng.cfm. [Accessed 13 December 2016].

- ↑ pp, 25 (2015) United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.ethnologue.com/country/GB (Accessed: 30 November 2016).

- ↑ Amharas are estimated to be the largest ethnic group of estimated 20.000 Ethiopian Germans|https://www.giz.de/fachexpertise/downloads/gtz2009-en-ethiopian-diaspora.pdf

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics 2014, The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS, 30 November 2016, <https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf>.

- ↑ Joireman, Sandra F. (1997). Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development. Universal-Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 1581120001.

The Horn of Africa encompasses the countries of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia. These countries share similar peoples, languages, and geographical endowments.

- ↑ Following the BGN/PCGN romanization employed for Amharic geographic names in British and American English.

- ↑ "Amhara/Abyssinian". Britanicca online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ Zegeye, Abebe (15 October 1994). Ethiopia in Change. British Academic Press. p. 13. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ Olson, James (1996). The Peoples of Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 27. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Getachew Mekonnen Hasen. Wollo, Yager Dibab, p. 11. Nigd Matemiya Bet (Addis Ababa), 1992.

- ↑ Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. "Amhara" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, p. 230. Harrassowitz Verlag (Wiesbaden), 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 Amhara people, Encyclopædia Britannica (2015)

- 1 2 3 4 Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- 1 2 3 Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

The analysis of linguistic distributions suggests that the proto-Ethiopians of the third millennium B.C. spoke languages derived from a single stock, that known as Hamito-Semitic or Afro-Asiatic. This ancestral language probably originated in the eastern Sahara, before the desiccation of that region... the homeland of Afro-Asiatic may have been in southwest Ethiopia. Wherever the origins of Afro-Asiatic, it seems clear that peoples speaking proto-Cushitic and proto-Omotic separated as groups with distinct languages by the fifth or fourth millennium BC and began peopling the Ethiopian plateaus not long after. Proto-Semitic separated at about the same time or somewhat earlier and passed over into Asia Minor... it seems reasonable to follow I. M. Diakonoff in assuming that the Semitic-speakers moved from the Sahara across the Nile Delta over Sinai, so that the presence of Semitic-speaking populations in Ethiopia must be attributed to a return movement of Semitic-speakers into Africa from South Arabia... As a base line for reconstructing the history of Greater Ethiopia, then, we may consider it plausible that by the end of the third millenium B.C. its main inhabitants were dark-skinned Caucasoid or "Afro-Mediterranean" peoples practicing rudimentary forms of agriculture and animal husbandry and speaking three branches of Afro-Asiatic -- Semitic, Cushitic and Omotic.

- ↑ Asafa Jalata (2004). State Crises, Globalisation and National Movements in North-East Africa: The Horn's Dilemma. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-134-27625-7.

- ↑ Mohammed Ali (1996). Ethnicity, Politics, and Society in Northeast Africa: Conflict and Social Change. University Press of America. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-0-7618-0283-9.

- ↑ E. A. Wallis Budge (2014). A History of Ethiopia: Volume I (Routledge Revivals): Nubia and Abyssinia. Routledge. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-1-317-64915-1.

- ↑ Ian Mortimer, The Fears of Henry IV (2007), p.111 ISBN 1-84413-529-2

- ↑ Beshah, pp. 13–4.

- ↑ Beshah, p. 25.

- ↑ Beshah, pp. 45–52.

- ↑ Kjetil Tronvoll, Ethiopia, a new start?, (Minority Rights Group: 2000)

- ↑ Peter Woodward, Conflict and peace in the Horn of Africa: federalism and its alternatives, (Dartmouth Pub. Co.: 1994), p.29.

- 1 2 3 4 Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. 56 & 175. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

Slavery was widespread in Greater Ethiopia until the 1930s, and today ex-slaves, children of former slaves, and de facto slaves in some regions occupy social positions much like their predecessors... members of any ethnic group were liable to be consigned to slavery by more powerful members of other tribes, if not their own tribe. (...) Afar made slaves of Amhara (...) Amhara and Tigreans, while not supposed to enslave fellow Christians, had slaves from many non-Christian groups.

- ↑ Amhara people; Alternative title: Abyssinian, Encyclopædia Britannica (2015)

- ↑ Mohammed Hassen (2015). The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700. Boydell & Brewer (Originally: Cambridge University Press). pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- ↑ Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- 1 2 Richard Pankhurst (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. pp. 122–123, 158, 243–249. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

Quote: Later in the century Mahfuz, the amir of Zayla, no doubt taking advantage of the wealth and power of the port, began a series of annual incursions, into Amhara, Shäwa and Fatagar. He assumed the religious title of Imam, symbolizing the fact that he was engaged in a jihad, or Holy War. His expeditions were accompanied by extensive looting and seizure of slaves, many of whom were assimilated in Adal, while others were exported. Mahfuz sent not a few as gifts to the rulers of Arabia, who in return gave him considerable military support.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6. Quote:: "The victorious Adal troops then burnt the houses, and churches, of the Christians, and carried off numerous women and children, besides much booty. (...) During his seven year reign, he [Jamal ad-Din] killed countless numbers of them, and took many more as slaves, who were then exported abroad. India, Arabia, Hormuz, Hejaz, Egypt, Syria, Greece, Iraq and Persia, as a result, became 'full of Abyssinian slaves'. He likewise captured many lands, 'increased the splendour' of Adal, and enriched himself with 'much booty', while 'a great multitude' of Amhara Christians at his exhortation embraced Islam."

- ↑ Ulrich Braukämper (2002). Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 30–32, 68–69, 76–78. ISBN 978-3-8258-5671-7.

Harb Jaus, a general of the Adalite sultan Djamal al-Din (d. AD 1433), before he continued his campaigns against the Christians in Dawaro, also achieved a successful attack on Bale. Makrizi's document reports, 'So much booty fell into his hands that every poor man was given three slaves; indeed by reason of the vast numbers of these the price of slaves fell.'

- ↑ Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya; Jean-Pierre Angenot (2008). Uncovering the History of Africans in Asia. BRILL Academic. p. 12. ISBN 978-90-474-3171-8. , Quote: "The ruling people of Ethiopia, the Amhara enslaved the Galla and other peoples in Ethiopia".

- ↑ J. Abbink (1992), An Ethno-Historical Perspective on Me'en Territorial Organization (Southwest Ethiopia), Anthropos, Bd. 87, H. 4/6, pp. 351-364, Quote: "Amhara slave raids and enforcement of the gäbbar system (a kind of serf-tribute system) were relaxed during Italian control of the area (1937-1940)."

- ↑ Ahmad, Abdussamad H. (1988). "Ethiopian Slave Exports at Matamma, Massawa and Tajura c. 1830 to 1885". Slavery & Abolition. Routledge. 9 (3): 93–102. doi:10.1080/01440398808574964.

Occasionally, slave raiders from northern Ethiopia kidnapped Amhara boys and girls and sold them (...)

- ↑ Ehud R. Toledano (2014). The Ottoman Slave Trade and Its Suppression: 1840-1890. Princeton University Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-1-4008-5723-4. , Quote: "The first section of this [slave] trade was in the hands of Ethiopian dealers who drove the slaves from the southern and southwestern Galla, Sidama and Gurage principalities to the central Amhara provinces. (...) the average Afar caravan consisted of thirty to fifty merchants and about two hundred slaves."

- ↑ Terence Walz; Kenneth M. Cuno (2010). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: Histories of Trans-Saharan Africans in Nineteenth-century Egypt, Sudan, and the Ottoman Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-977-416-398-2.

Although references to non-Oromo Abyssinian slaves from other parts of the highlands or coastal areas were not uncommon in the Ottoman era court records, by the nineteenth century such homelands are rarely mentioned. Many slaves called themselves Galla, a derogatory term used by northern Amhara for other Amhara who had intermarried with the slave-raided Oromo, no doubt adapting the name from slave-dealers.(...) ...in fact it was not likely that Amhara themselves were enslaved in his [Ali Mubarak's] day since they were the ruling ethnic (and mostly Christian) group in the Abyssinian highlands, whose warlords were one of many groups that habitually raided elsewhere for slaves.

- ↑ Arén, Gustav (1978). Evangelical Pioneers in Ethiopia: Origins of the Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus. EFS-förl. p. 136. ISBN 9170803641. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

Ethiopian law did not forbid the holding of slaves, only enslavement of Christians.

- ↑ George Arthur Lipsky (1962). Ethiopia: Its People, Its Society, Its Culture, Volume 9. Hraf Press. p. 37.

although the Orthodox Christian Amharas and Tigrais make up only a third of the population, more than this proportion are estimated to be Orthodox Christians. Traditionally, there has been resistance to converting (or in the Amharic phrase, "raising") the non-Christian ethnic groups to Christianity, since they then could not be kept or sold as slaves.

- ↑ Willis, John Ralph (2005). Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two: The Servile Estate. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 1135780161. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

Quote: With few exceptions, slavers were careful not to purchase Christian-Amhara or Tigrean slaves, nor did they purchase Muslim ones.

- 1 2 Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

- ↑ Allan Hoben (1970). "Social Stratification in Traditional Amhara Society". In Arthur Tuden and Leonard Plotnicov. Social stratification in Africa. New York: The Free Press. pp. 210–211, 187–221. ISBN 978-0029327807.

- ↑ Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. Praeger. pp. 57–60.

There was a clear distinction between 'red' and 'black' slaves, Hamitic and negroid respectively; the Shanqalla (negroids) were far cheaper as they were destined mostly for hard work around the house and in the field... While in the houses of the brokers, the [red] slaves were on the whole well treated.

- ↑ Eike Haberland (1979), Special Castes in Ethiopia, in Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies, Editor: Robert Hess, University of Illinois Press,

OCLC 7277897, pp. 129-132 (also see pp. 134-135, 145-147);

Amnon Orent (1979), From the Hoe to the Plow, in Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies, Editor: Robert Hess, University of Illinois Press, OCLC 7277897, p. 188, Quote: "the Mano, who are potters and leather craftsmen and considered 'unclean' in the usual northern or Amhara understanding of caste distinction; and the Manjo, the traditional hunters and eaters of 'unclean' foods – hippopotamus, monkey and crocodile." - ↑ Teshale Tibebu (1995). The Making of Modern Ethiopia: 1896-1974. The Red Sea Press. pp. 67–70. ISBN 978-1-56902-001-2. , Quote: "Interestingly enough, while slaves and ex-slaves could 'integrate' into the larger society with relative ease, this was virtually impossible for the occupational minorities ('castes') up until very recently, in a good many cases to this day."

- ↑ Christopher R. Hallpike (2012, Original: 1968), The status of craftsmen among the Konso of south-west Ethiopia, Africa, Volume 38, Number 3, Cambridge University Press, pages 258, 259-267, Quote: "Weavers tend to be the least and tanners the most frequently despised. In many cases such groups are said to have a different, more negroid appearance than their superiors. There are some instances where these groups have a religious basis, as with the Moslems and Falashas in Amhara areas. We frequently find that the despised classes are forbidden to own land, or have anything to do with agricultural activities, or with cattle. Commensality and marriage with their superiors seem also to be generally forbidden them."

- ↑ Todd, David M. (1977). "Caste in Africa?". Africa. Cambridge University Press. 47 (04): 398–412. doi:10.2307/1158345.

Dave Todd (1978), "The origins of outcastes in Ethiopia: reflections on an evolutionary theory", Abbay, Volume 9, pages 145-158 - ↑ Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

, Quote: "As Herbert Lewis has observed, if the term caste can be used for any social formation outside of the Indian context, it can be applied as appropriately to those Ethiopian groups otherwise known as 'submerged classes', 'pariah groups' and 'outcastes' as to any Indian case.";

Lewis, Herbert S. (2006). "Historical problems in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Wiley-Blackwell. 96 (2): 504–511. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50145.x. , Quote (p. 509): "In virtually every Cushitic group there are endogamous castes based on occupational specialization (such caste groups are also found, to some extent, among the Ethiopian Semites).". - ↑ Niall Finneran (2013). The Archaeology of Ethiopia. Routledge. pp. 14–15. ISBN 1-136-75552-7. , Quote: "Ethiopia has, until fairly recently, been a rigid feudal society with finely grained perceptions of class and caste".

- ↑ Central Statistical Agency. 2010. Population and Housing Census 2007 Report, National. [ONLINE] Available at: http://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/catalog/3583/download/50086. [Accessed 13 December 2016].

- ↑ "Amharic language". Ethnologue. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

The origins and early history of the Amhara remain the subject of some speculation. Archaeological evidence suggests that sometime before 500 B.C.E. a Semitic-speaking people, from whom the Amhara are descended, migrated from present-day Yemen to the area of northern Ethiopia that would become Aksum. These Himyarites, as they have come to be called, intermarried with indigenous speakers of Cushitic languages, such as Agaw, and gradually spread south into the present-day homeland of the Amhara. Their descendants spoke Ge'ez, and ancient Semitic tongue that is no longer spoken but remains the official language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

- ↑ Danver, Steven Laurence. Native Peoples Of The World. 1st ed. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, an imprint of M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2013. Print.

- ↑ Bernard Collins (The Abyssinians) Interview Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.. Published 4 November 2011 by Jah Rebel. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ "FDRE States: Basic Information – Amhara". Population. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- 1 2 "African Marriage ritual". Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East, Part 2, Volume 23. Greystone Press. 1967. p. 300. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ↑ Donald N. Levine (2000). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-226-47561-5.

- ↑ Donald N. Levine (2000). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-226-47561-5.

- ↑ W. A. Shack (1974). Ethnographic Survey of Africa. International African Institute. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-0-85302-040-0.

- 1 2 3 Amhara people Encyclopædia Britannica (2015)

- 1 2 David Levinson (1995). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Africa and the Middle East. G.K. Hall. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8161-1815-1. , Quote: "Temporary marriage (damoz) obliges the husband to pay housekeeper's wages for a period stated in advance. (...) The contract, although oral, was before witnesses and was therefore enforceable by court order. The wife had no right of inheritance, but if children were conceived during the contract period, they could make a claim for part of the father's property, should he die."

- ↑ Weissleder, W. (2008). "Amhara Marriage: The Stability of Divorce". Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie. Wiley-Blackwell. 11 (1): 67–85. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618x.1974.tb00004.x.

- ↑ Donald N. Levine "Amhara," in von Uhlig, Siegbert, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica:A-C, 2003, p.231.

- 1 2 Takkele Taddese "Do the Amhara Exist as a Distinct Ethnic Group?" in Marcus, Harold G., ed., Papers of the 12th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, 1994, pp.168–186.

Further reading

- Wolf Leslau and Thomas L. Kane (collected and edited), Amharic Cultural Reader. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2001. ISBN 3-447-04496-9.

- Donald N. Levine, Wax & Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopian Culture (Chicago: University Press, 1972) ISBN 0-226-45763-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amhara. |

- Lemma, Marcos (MD, PhD). "Who ruled Ethiopia? The myth of 'Amara domination'". Ethiomedia.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2005. Retrieved 28 February 2005.

- People of Africa, Amhara Culture and History

- ↑ , Ethiopian Government Portal