Syriac Orthodox Church

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

Subdivisions

|

|

History and theology

|

|

Major figures

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Eastern liturgical rites |

|

The Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch (Classical Syriac: ܥܺܕܬܳܐ ܣܽܘ̣ܪܝܳܝܬܳܐ ܬܪܺܝܨܰܬ ܫܽܘ̣ܒ̥ܚܳܐ, translit. ʿĪṯo Suryoyṯo Trišaṯ Šubḥo; Arabic: الكنيسة السريانية الأرثوذكسية), or Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East, is an Oriental Orthodox Church with autocephalous patriarchate established by Severus of Antioch in Antioch in 518, tracing its founding to Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the 1st century, according to its tradition.[9][10][11] The Church uses the Divine Liturgy of Saint James, associated with St. James, the "brother" of Jesus and patriarch among the Jewish Christians at Jerusalem.[12] Syriac is the official and liturgical language of the Church based on Syriac Christianity. The primate of the church is the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch currently H.H. Ignatius Aphrem II since 2014, seated in Cathedral of Saint George, Bab Tuma, Damascus, Syria.[13][14]

History

The church claims apostolic succession through the pre-Chalcedonian Patriarchate of Antioch to the Early Christian communities established by Saint Peter in Antioch, Roman Empire, in Apostolic era, as described in the Acts of the Apostles (New Testament, Acts 11:26). Saint Evodius was bishop of Antioch until 66 AD, and was succeeded by Saint Ignatius of Antioch.[15]In A.D 169 Theophilus of Antioch wrote sole surviving work consists of three apologetic tracts to Autolycus.[16]Patriarch Babylas of Antioch was considered the first saint recorded as having had his remains moved or "translated" for religious purposes; a practice that was to become extremely common in later centuries.[17].Eustathius of Antioch supported Athanasius of Alexandria who opposed the followers of the condemned doctrine of Arius (Arian controversy) at the First Council of Nicaea.[18] During the time of Meletius of Antioch the church split due to his deposition for Homoiousian leanings which resulted in the Meletian Schism, which saw several groups and several claimants to the see of Antioch.[19][20][21]

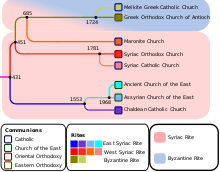

The patriarchate was forced to move from Antioch in A.D. 518 due to emperor Justin I, who enforced a uniform Chalcedonian Christian orthodoxy throughout the empire.[22][23][24][25]. In circa 518, the Syriac Orthodox Church continued to recognize Patriarch Severus of Antioch as the legitimate patriarch despite his deposition by the Byzantine Empire while those who sought communion with Rome accepted the Council of Chalcedon and the formula of Pope Hormisdas, and recognized the new Chalcedonian patriarch of Antioch Paul the Jew. Patriarch Severus of Antioch was a significant bishop in the organisation of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, Byzantine Empire, after he was expelled from Antioch in 518. Bishop Jacob Baradaeus (died 578) is credited for ordaining the majority of the miaphysite hierarchy while facing heavy persecution in the 6th century. Around 1665, many Saint Thomas Christians of Kerala, India, affirmed allegiance to the Syriac Orthodox Church, establishing the Malankara Syrian Church reuniting with the See of Antioch for the first time since the schism of the Church of the East from the jurisdiction of Antioch in 484 after the execution of Babowai. In the Fertile Crescent, controversy occurred in 1783 when a few members of its hierarchy entered in full communion with the Catholic Church, establishing the Syriac Catholic Church as part of the Eastern Catholic Churches. Despite this, the Syriac Orthodox Church remains significantly larger in members and clergy than the Syriac Catholic Church.

Although originally established in Antioch, due to persecution, first by the Chalcedonian Romans followed by the Muslim Arabs, the church's patriarchate was subsequently seated in Mor Hananyo Monastery, Mardin, Ottoman Empire (1160-1933), whereafter Homs (1933-1959), and Damascus, Syria, since 1959. A diaspora has also spread from the Levant, Iraq, and Turkey throughout the world, notably in Sweden, Germany, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Austria, France, United States, Canada, Guatemala, Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand.

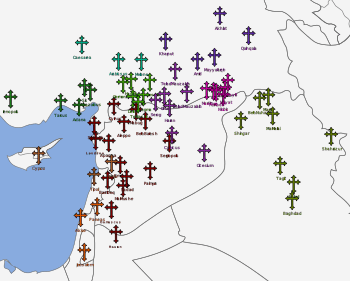

The church's members are divided in 26 archdioceses, and 11 patriarchal vicariates. Its original area is present-day Syria, Turkey, and Iraq.[26]

The Syriac Orthodox Church participates in ecumenical discussions, being a member of the World Council of Churches since 1960, and of the Middle East Council of Churches since 1974. The precise differences in theology that caused the Chalcedonian controversy is said to have arisen "only because of differences in terminology and culture and in the various formulae adopted by different theological schools to express the same matter", according to a common declaration statement between Patriarch Ignatius Jacob III of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch and Pope Paul VI of the Roman Catholic Church on Wednesday 27 October 1971 and again in the common declaration statement between Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch and Pope John Paul II of the Roman Catholic Church on Saturday 23 June 1984. The church is often referred to as the Jacobite Church (after Jacob Baradaeus), but it rejects this name due to its Apostolic origin.

The Syriac Orthodox Church is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, a distinct communion of churches claiming to continue the patristic and Apostolic Christology before the schism following the Council of Chalcedon in 451.[5]

Apostolic succession

The Syriac Orthodox Church claims the status as the most ancient Christian church in the world by apostolic succession from the Patriarchate of Antioch. According to Saint Luke, "The disciples were first called Christians in Antioch" (New Testament, Acts 11:26). Saint Peter and Saint Paul are regarded as the co-founders of the Patriarchate of Antioch in AD 37, with Saint Peter serving as its first bishop and considered the first patriarch of and by the Syriac Orthodox Church having been selected by the founder of the church Jesus Christ.[27][28] When Saint Peter left Antioch, Evodios and Ignatius presided over the Patriarchate of Antioch. Because of the significance attributed to Saint Ignatius in the Syriac Orthodox Church, almost all of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchs since 1293 have applied the name of Ignatius in the title of the Patriarch preceding their own patriarchal name.[29]

Patriarchate of Antioch

Given the antiquity of the bishopric of Antioch and the importance of the Christian community in the city of Antioch - a commercially significant city in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire - the First Council of Nicaea (325) recognised the bishopric as a primacy (patriarchate) along with the bishoprics of Rome, Alexandria, and Jerusalem, bestowing authority for the "Church of Antioch and All of the East" on the Patriarch.[30][31]

%2C_overlooking_Bashiqa_and_Bartella%2C_between_the_Kurdistan_Region_and_Iraq_22.jpg)

Even though the Synod of Nicaea was convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine, the authority of the ecumenical synod was also accepted by the church in the Persian Empire, which was politically isolated from the churches in the Roman Empire. Until 482, this church accepted the spiritual authority of the Patriarch of Antioch. The church also maintained a smaller non-Chalcedonian church under a Catholicos, known by the title Maphryānā, until the 1860s. This Catholicate was canonically transferred to India in 1964, as Catholicos of India and continues today as Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church, an integral part of the Syriac Orthodox Church with the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch as its head.

The Christological controversies that followed the Council of Chalcedon in 451 resulted in a long struggle for the Patriarchate between those who accepted and those who rejected the Council.[32] In 518, Patriarch Severus of Antioch was exiled from the city of Antioch and took refuge in Alexandria. Non-Chalcedonians continued to recognize Severus as the legitimate patriarch even after his exile in 518 until his death in 538. Jacob Baradeus continued to ordain patriarchs after Severus continuing the Non-Chalcedonian succession of patriarchs of the Church of Antioch, in opposition to the government-backed Patriarchate of Antioch occupied by the pro-Chalcedonian partisans, today known as Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch; leading to its being known popularly as the "Jacobite" Church while the Chalcedonian entity were known popularly as Melkites coming from the Syriac word for king (malka), an implication of the Chalcedonian church's relationship to the Roman Emperor. On account of many historical upheavals and consequent hardships which the church had to undergo, the Patriarchate was transferred to different monasteries in Mesopotamia for centuries.

In about 1160[33] its seat was transferred from Antioch to the Mor Hananyo Monastery (Deir al-Za`faran), in southeastern Turkey near Mardin, where it remained until 1933. They reestablished themselves in Homs, Syria due to an adverse political situation in Turkey. In 1959 it was then transferred to Damascus, where it currently resides. The Patriarchate is now situated in Bab Tuma, Damascus, capital of Syria; but the Patriarch resides at the Mar Aphrem Monastery in Maarat Saidnaya, located about 25 kilometers north of Damascus.

Ecumenical relations

The Bishops of Antioch played a prominent role in the first three synods held at Nicaea (325), Constantinople (381), and Ephesus (431), shaping the formulation and early interpretation of Christian doctrines.

In terms of Christology, the Oriental Orthodox (Non-Chalcedonian) understanding is that Christ is "One Nature—the Logos Incarnate, of the full humanity and full divinity". Just as humans are of their mothers and fathers and not in their mothers and fathers, so too is the nature of Christ according to Oriental Orthodoxy. The Chalcedonian understanding is that Christ is "in two natures, full humanity and full divinity". This is the doctrinal difference which separated the Oriental Orthodox from the rest of Christendom.

By the 20th century the Chalcedonian schism was not seen with the same relevance, and from several meetings between the authorities of the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodoxy, reconciling declarations emerged in the common statement of the Oriental Orthodox Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas and Pope John Paul II in 1984.

| “ | The confusions and schisms that occurred between their Churches in the later centuries, they realize today, in no way affect or touch the substance of their faith, since these arose only because of differences in terminology and culture and in the various formulae adopted by different theological schools to express the same matter. Accordingly, we find today no real basis for the sad divisions and schisms that subsequently arose between us concerning the doctrine of Incarnation. In words and life we confess the true doctrine concerning Christ our Lord, notwithstanding the differences in interpretation of such a doctrine which arose at the time of the Council of Chalcedon.[34] | ” |

The Syriac Orthodox Church is active in ecumenical dialogues. It has been a member church of World Council of Churches since 1960 and Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas is one of the presidents of World Council of Churches. The Syriac Orthodox Church is also involved in ecumenical dialogues with the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox churches. There are common Christological and pastoral agreements with the Catholic Church. It has also been involved in the Middle East Council of Churches since 1974.

Since 1998, the heads of the three Oriental Orthodox churches in the Eastern Mediterranean i.e. the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church meet regularly each year.[29]

Worship

Prayer

Syriac Orthodox clergy and some devout laity follow a regimen of seven prayers a day, in accordance with Psalm 119.[35] According to the Syriac tradition, an ecclesiastical day starts at sunset:

- Evening or Ramsho prayer (Vespers)

- Night prayer or Sootoro prayer (Compline)

- Midnight or Lilyo prayer (Matins)

- Morning or Saphro prayer (Prime or Lauds, 6 a.m.)

- Third Hour or tloth sho`in prayer (Terce, 9 a.m.)

- Sixth Hour or sheth sho`in prayer (Sext, noon)

- Ninth Hour or tsha` sho'in prayer (None, 3 p.m.)

Liturgy

The liturgical service, which is called Holy Qurbono in Syriac Aramaic and means "Eucharist", is celebrated on Sundays and special occasions. The Holy Eucharist consists of Gospel reading, Bible readings, prayers, and songs. During the celebration of the Eucharist, priests and deacons put on elaborate vestments unique to the Syriac Orthodox Church. Whether in the Eastern Mediterranean, India, Europe, the Americas or Australia, the same vestments are worn by all clergy.

Apart from certain readings, all prayers are sung in the form of chants and melodies. Hundreds of melodies remain preserved in the book known as Beth Gazo. It is the key reference to Syriac Orthodox church music.[36]

Bible in the Syriac tradition

Syriac Orthodox Churches use the Peshitta (Syriac: simple, common) as its Bible. The New Testament books of this Bible are estimated to have been translated from Greek to Syriac between the late 1st century to the early 3rd century AD.[37] The Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated from Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century. The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books, had become the standard by the early 5th century, replacing two early Syriac versions of the gospels.

Clergy

Patriarch

The supreme head of the Syriac Orthodox Church is named Patriarch of Antioch, in reference to his titular pretense to one of the five patriarchates of the Pentarchy of early Eastern Christianity. Considered the "father of fathers", he must be an ordained bishop.

Bishops

The Bishop title comes from Episcopos, a word that means "the one who oversees". In the Syriac Orthodox Church, a bishop is a spiritual ruler of the church. Bishops too have different ranks. The highest is the Patriarch. Next to him is the Catholicos of India, also known as Maphrian, who is the head of the integral Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church in India. Then there are Metropolitan bishops or Archbishops, and under them there are bishops.[38] Historically, in the Malankara Church, the Archbishop was called as Archdeacon, who was the local chief and/or ecclesiastical authority of the Saint Thomas Christians in the Malabar region of India.

Priests

The priest is the seventh rank and is the duly one appointed to administer the sacraments. Unlike in the Catholic Church, Syriac deacons may marry before ordained as priests; however they may not marry after ordained as priests. There is an honorary rank among the priests that is Corepiscopos who has the privileges of "first among the priests" and are given a chain with cross and specific vestment decorations. Corepiscopos is the highest rank a married man can be elevated to in the Syriac Orthodox Church. Any ranks above the Corepiscopos are unmarried.

Deacons

In the Syriac Orthodox tradition, different ranks among the deacons are specifically assigned with particular duties. The six ranks of diaconate are:

- ‘Ulmoyo (Faithful)

- Mawdyono (Confessor of faith)

- Mzamrono (Singer)

- Quroyo (Reader)

- Afudyaqno (Sub-deacon)

- Masamsono (Full deacon)

Only a full deacon or Masamsono can take the censer during the Divine Liturgy to assist the priest. However, in Malankara Syriac Orthodox Church, because of the lack of deacons, altar assistants who do not have any rank of deaconhood may assist the priest. The deacons in Malankara Syriac Orthodox Church are allowed to wear a phiro, a cap. Historically the Malankara Church were administered by a local chief called Archdeacon ("Arkadiyokon").

Vestments

The clergy of the Syriac Orthodox Church have unique vestments that are quite different from other Christian denominations. The vestments worn by the clergy vary with their order in the priesthood: the deacons, the priests, the bishops, and the patriarch each have different vestments.

Bishops usually wear a black or a red robe with a red belt. They do not, however, wear a red robe in the presence of the patriarch, who wears a red robe. Bishops visiting a diocese outside their jurisdiction also wear black robes in deference to the bishop of the diocese, who alone wears red robes.

A priest also wears phiro, or a cap, which he must wear for all the public prayers. Monks also wear eskimo, a hood. Priests also have ceremonial shoes which are called msone. Without wearing these shoes, a priest cannot distribute Eucharist to the faithful. Then there is a white robe called kutino symbolising purity. Hamniko or stole is worn over this white robe. Then he wears a girdle called zenoro, and zende, meaning sleeves. If the celebrant is a bishop, he wears a masnapto, or turban (different from the turbans worn by Sikh men). A cope called phayno is worn over these vestments. Batrashil, or pallium, is worn over the phayno by bishops, similar to hamnikho worn by priests.[39] An important aspect is that bishops and Corepiscopos have hand-held crosses while ordinary priests have none.

The priest's usual dress is a black robe. However, in India, due to the hot weather, priests usually wear white robes except when during prayers in the church, when they wear a black robe over the white one.

Primacy of Saint Peter

The fathers of the Syriac Orthodox Church tried to give a theological interpretation to the primacy of Saint Peter. They were fully convinced of the unique office of Peter in the early Christian community. Ephrem, Aphrahat and Maruthas who were supposed to be the best exponents of the early Syriac tradition unequivocally acknowledged the office of Peter.

The Syriac Church Fathers following the rabbinic tradition call Jesus "Kepha" for they see "rock" in the Old Testament as a messianic symbol. When Christ gave his own name "Kephas" to Simon, he was giving him participation in the person and office of Christ. Christ who is the Kepha and shepherd made Simon the chief shepherd in his place and gave him the very name Kephas and said that on Kephas he would build the Church. Aphrahat shared the common Syriac tradition. For him Kepha is in fact another name of Jesus, and Simon was given the right to share the name. The person who receives somebody else's name also obtains the rights of the person who bestows the name. Aphrahat makes the stone taken from Jordan a type of Peter. He says Jesus, son of Nun, sets up the stones for a witness in Israel; Jesus our saviour called Simon Kepha Sarirto and set him as the faithful witness among nations.

Again he says in his commentary on Deuteronomy that Moses brought forth water from "rock" (Kepha) for the people and Jesus sent Simon Kepha to carry his teachings among nations. God accepted him and made him the foundation of the church, and called him Kepha. When he speaks about the transfiguration of Jesus he calls him Simon Peter, the foundation of the church. Ephrem also shared the same view. The Armenian version of Aldhelm's De Virginitate records that Peter the rock shunned honour who was the head of the apostles. In a mimro of Ephrem found in holy week liturgy points to the importance of Peter.[40]

Both Aphrahat and Ephrem the Syrian represent the authentic tradition of the Syriac church. The different orders of liturgies used for sanctification of church buildings, marriages, ordinations etc., reveal that the primacy of Peter is a part of living faith of the Syriac Orthodox Church.[41]

However, Syriac Orthodox don't believe that Saint Peter is indicative of the Papal primacy as understood by the Roman See, rather, "Petrine primacy" according to the ancient Syriac tradition.

Global presence

Demography

It is estimated that the church has 500,000 Syriac-Aramean adherents[5][6] in addition to 1.2 million members of the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church in India.[7] Historically, the followers of the church are mainly ethnic Syriacs/Assyrians, who comprise the indigenous pre-Arab populations of modern Syria, Iraq and south eastern Turkey.[42] Additionally, there is also a large Syriac community among Mayan converts in Guatemala. In addition, there are a few other autocephalous (independent) Syriac Orthodox Churches following the same or similar liturgy and the same West Syriac rite Christianity including the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and Mar Thoma Syrian Church, both based in India and followed by ethnic Indian St Thomas Christians.

According to 2001 estimates, around 260,000 ethnic Syriacs live in the Middle East. A similar number live in Western Europe and North America, most notably in Sweden and Germany (100,000), and the Americas (50,000).[43] In terms of specifics, There are 170,000 Syriac Orthodox members in Syria, 50,000 in Iraq and 15,000 in Turkey.[43][44] However, The number of Syriacs in Turkey is rising, due to refugees from Syria and Iraq fleeing ISIS, as well as Syriacs from the Diaspora who fled the region during the Turkey-PKK conflict (which occurred from the late seventies until the late 90s) returning and rebuilding their homes. A specific instance of this occurred in Elbegendi, where a German Syriac returned to his village with a few other families and rebuilt the town together with money earned abroad. In addition to those larger populations of Syriacs, 5,000 live in Palestine (500 in Jerusalem and 5,000 Bethlehem), and around 50,000 are estimated to live in Lebanon.

In the Assyrian/Syriac diaspora, there are approximately 80,000 members in the United States, 80,000 in Sweden, 100,000 in Germany, 15,000 in the Netherlands, 200,000 members in Brazil, Switzerland, and Austria and a large number living in Central America, which is mainly made up of indigenous Mayan converts in Guatemala, in addition to the 1.5 million adherents of the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church and their own ethnic diaspora.[45]

Official name

_-_Copy.jpg)

Since the church has never been the officially adopted religion of a modern-day country, a unique name had long been used to distinguish the church from the polity of Syria in most languages besides English. This includes Arabic (the official language of Syria), where the Church has always been known as the "Syriani" church; the term "Syriani" being the same word used to identify the Syriac language in Arabic. Being the lone exception up until the year 2000, English identified the church mainly as the "Syrian" Orthodox Church; with "Syrian" being derived from the term "Syrian church" used by English-speaking historians to describe the community in ancient Syria prior to the Nestorian/Jacobite split in the 5th century. (see: Christianity in Syria). Syriac-speaking Christians have historically referred to themselves as Suraye/Suryaye, literally "Syriac", leading to most members favoring the term "Syriac Orthodox". However, some Assyrian nationalists have favored the term "Assyrian Orthodox", arguing it was more accurate because the term Syria is now generally accepted as an Indo-European (Luwian) corruption of Assyria (see Name of Syria). The name "Syrian" Orthodox Church failed to distinguish the church in English which uses "Syrian" to designate all things generally related to Syria. In the similar way, the term Assyrian Orthodox Church also led to confusion with the Assyrian Church of the East, itself renamed from the Church of the East in 1976. Hence, in 2000, a Holy Synod ruled that the church should be named after its official liturgical language of Syriac (i.e. Syriac Orthodox Church), as it is in most other languages. The official name of the church in Syriac is pronounced ʿĒdtō Suryōytō Triṣaṯ Šuḇḥō; this name has not changed, nor has it changed in any language other than English.[47] The church is often referred to as Jacobite (after Jacob Baradaeus), but it rejects this name.

Institutions

The church today has two seminaries, and numerous colleges and other institutions. Among those there are several religious institutions which are noteworthy. Patriarch Aphrem I Barsoum (†1957) established St. Aphrem's Clerical School in 1934 in Zahlé, Lebanon. In 1946 it was moved to Mosul, Iraq, where it provided the Church with a good selection of graduates, the first among them being Patriarch Mor Ignatius Zakka I Iwas and many other church leaders. Also the church has an international Christian education centre which is a centre for religious education , The Antioch Syrian University at Maaret Sidnaya, Damascus.[48] . In 1990 he established the Order of St. Jacob Baradaeus for nuns and renovated St. Aphrem's Clerical building in Atshanneh, Lebanon for the new order.[49]

Two new seminaries have been instituted in Sweden and in Salzburg, Austria for the study of the Syriac Church, Syriac theology, Syriac history and Syriac language and culture.

Jurisdiction of the Patriarchate

The Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch originally covered the whole region of the Middle East and India. However, in recent centuries, its parishioners started to emigrate to other countries all over the world. Today, the Syriac Orthodox Church has several Archdioceses and Patriarchal Vicariates (exarchates) in many countries covering six continents.

Asia

.jpg)

- The Patriarch of Antioch and All the East, the Supreme Head of the Universal Syriac Orthodox Church Ignatius Aphrem II.

- Patriarchal Office Director in Damascus Archbishop Mor Timotheus Matta Al-Khoury.

- Archbishopric of Jazirah and Euphrates under the spiritual guidance and direction of acting Archbishop Mor Timotheus Matta Al-Khoury.

- Archbishopric of Aleppo under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Gregorios Yohanna Ibrahim (de).[note 1]

- Archbishopric of Homs & Hama under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Selwanos Petros AL-Nemeh.

- Patriarchal Vicariate for the Archdiocese of Damascus under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Timothius Matta AlKhouri.

.

- Iraq

- Archbishopric of Baghdad and Basrah under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Severius Jamil Hawa.

- Archbishopric of Mosul, Kirkuk and Kurdistan under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Nicodimus Dawood Sharaf. Served previously by the retired Archbishop but currently Patriarch Advisor Mor Gregorius Saliba Shamoun.

- Archbishopric of St Matthew's Monastery under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Timothius Mousa A. Shamani.

- Iraq

- Lebanon

- Archbishopric of Mount Lebanon under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Theophilos George Saliba.

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Zahle under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Yostinos Boulos Safar.

- Archbishopric of Beirut & Benevolent institutions in Lebanon under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Clemis Daniel Malak Kourieh.

- The Patriarchal Institutions in Lebanon under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Chrysostoms Michael Shimon.

- Lebanon

- Turkey

- Archbishopric of Istanbul and Ankara under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Filüksinos Yusuf Çetin.

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Mardin under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Filüksinos Saliba Özmen.

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Turabdin under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Timothius Samuel Aktaş.

- Archbishopric of Adiyaman under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Gregorius Melki Ürek.[51]

- Turkey

- UAE

- Patriarchal Vicariate of UAE and Arab States of the Persian Gulf under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Bartholomaus Nathanael.

- UAE

- The Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, one of the various Saint Thomas Christian churches in India, is an integral part of the Syriac Orthodox Church, with the Patriarch of Antioch as its supreme head. The local head of the church in Malankara (Kerala) is Baselios Thomas I, ordained by Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas in 2002 and accountable to the Patriarch of Antioch. The headquarters of the church in India is at Puthencruz near Ernakulam in the state of Kerala in South India.

- The Knanaya Syriac Orthodox Church is an archdiocese under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Severious Kuriakose with the same patriarchate as its supreme head.

- Simhasana Churches and Evangelistic Association Of The East (E.A.E) the first missionary association of Syriac Orthodox Church, is under direct control of H.H. Ignatius Aphrem II.

- The Indian or Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, is not affiliated with the Universal Syriac Orthodox Church.

- Unlike most other patriarchal churches abroad, the language of the Syriac Orthodox Divine Liturgy in India is mostly in Malayalam along with Syriac. This is because almost all Syriac Christians in India hail from the State of Kerala, where Malayalam is the mother tongue of the people.

Bethel Suloko Church, Perumbavoor, India

Bethel Suloko Church, Perumbavoor, India

Europe

- Belgium

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Belgium, France and Luxembourg under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor George Kourieh[52]

- Belgium

- Netherlands

- Patriarchal Vicariate of the Netherlands under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Polycarpus Augin (Eugene) Aydın.

- Netherlands

- Sweden

- Archbishopric of Sweden and Scandinavia under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Julius Abdulahad Gallo Shabo.

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Sweden under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Dioskoros Benyamen Atas.

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Switzerland and Austria under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Dionysius Isa Gürbüz.[53]

- Switzerland

- United Kingdom

- Patriarchal Vicariate of the United Kingdom under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Athanasius Toma Dawod.

- Gallery

- United Kingdom

St.Kuriakose Church, Vallby, Västerås

St.Kuriakose Church, Vallby, Västerås- Monastery of Mor Ya`qub of Sarug in Warburg

Interior of Saint Stephen church in Gütersloh, Germany

Interior of Saint Stephen church in Gütersloh, Germany- St.Avgin Monastery,Arth,Switzerland

North America

- United States

- Patriarchal Vicariate of the Eastern United States under the spiritual guidance and direction of the Patriarch Ignatius Aphrem II and assisted by Archbishop Mor Dionysius Jean Kawak.

- Patriarchal Vicariate of the Western United States under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Clemis Eugene Kaplan.

- Malankara Archdiocese of North America under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Titus Yeldho Pathickal.

- United States

Central America, the Caribbean Islands, and Venezuela

- Guatemala

- Archdiocese of Central America, the Caribbean Islands and Venezuela under the spiritual guidance and direction of Archbishop Mor Yaqub Eduardo Aguirre Oestmann.

- Guatemala

South America

Oceania

- Australia and New Zealand

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Australia and New Zealand under Archbishop Mor Malatius Malki Malki [55]

- Australia and New Zealand

- St. Ephraim Church, Lidcombe

Gallery

Peshitta Bible at Mor Hananyo Monastery

Peshitta Bible at Mor Hananyo Monastery Syrian orthodox church Al-Hasakah

Syrian orthodox church Al-Hasakah Rasal-Ain Church

Rasal-Ain Church Syriac Orthodox abbey in Mardin

Syriac Orthodox abbey in Mardin Church Destroyed during War

Church Destroyed during War- 1915 Sayfo Monument

See also

- List of Syriac Orthodox Patriarchs of Antioch

- Syriac Orthodox Church in the Middle East

- Dioceses of the Syriac Orthodox Church

- Council of Capharthutha

Syriac Christianity in India

- Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church

- Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Indian Orthodox Church)

Ethnic Communities

- Syriac Orthodox Christians (Middle East)

- Nasranis

- Guatemalans (recent convert activity)

Other

Notes

- ↑ In 2013, Mor Gregorios Yohanna Ibrahim along with Paul (Yazigi) was abducted by militants in the Syrian Civil War, his whereabouts is currently unknown.[50]

References

- ↑ "Cave Church of St. Peter - Antioch, Turkey". www.sacred-destinations.com.

- ↑ "Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East — World Council of Churches". Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ↑ "History of Syriac Orthodox Church". Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch.

- ↑ https://www.oikoumene.org/en/member-churches/syrian-orthodox-patriarchate-of-antioch-and-all-the-east

- 1 2 3 "CNEWA - The Syrian Orthodox Church". www.cnewa.org.

- 1 2 "Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch - Dictionary definition of Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch - Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ "Adherents.com". www.adherents.com.

- ↑ Taylor, William (2014). Narratives of Identity: The Syrian Orthodox Church and the Church of England 1895-1914. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443869461.

- ↑ "Syriac Orthodox Church - A Brief Overview". sor.cua.edu. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ Gregorios, Paulos (1999). Introducing the Orthodox Churches. ISPCK. ISBN 9788172144876.

- ↑ "Saint James apostle, the Lord's brother". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ "The Hidden Pearl: The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage". Trans World Film Italia. 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Lukenbill, W. Bernard (2012). Research in Information Studies: A Cultural and Social Approach. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781469179612.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Evodius". www.newadvent.org.

- ↑ Theophilus of Antioch (Roberts-Donaldson).

- ↑ Eduard Syndicus; Early Christian Art; p. 73; Burns & Oates, London, 1962

- ↑ Sellers, Robert Victor (1927). "Eustathius of Antioch and His Place in the History of Early Christian Doctrine".

- ↑ Stillingfleet, Edward (1685). Origines Britannicæ [i.e., Britannicae], Or, The Antiquities of the British Churches: With a Preface Concerning Some Pretended Antiquities Relating to Britain, in Vindication of the Bishop of St. Asaph. M. Flesher.

- ↑ "Meletian Schism | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ General History of the Christian Religion and Church. Crocker & Brewster. 1855.

- ↑ Menze, Volker L. (2008). Justinian and the Making of the Syrian Orthodox Church. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191560095.

- ↑ "Severus of Antioch | Greek theologian". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ HONIGMANN, ERNEST (1947). "THE PATRIARCHATE OF ANTIOCH: A Revision of Le Quien and the Notitia Antiochena". Traditio. pp. 135–161.

- ↑ "General History". Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. 1 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Syriac Orthodox Church Today". sor.cua.edu.

- ↑ BARRATT, PETER J. H. (2014). Absentis: St Peter, the Disputed Site of His Burial Place and the Apostolic Succession. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781493168392.

- ↑ Gould, Sabine Baring (1872). The lives of the saints. 12 vols. [in 15].

- 1 2 Chaillot, Christine. The Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch and All the East. Geneva: Inter-Orthodox Dialogue, 1988.

- ↑ Wordsworth, Christopher (1881). A Church History to the Council of Nicaea, A.D. 325. Rivingtons.

- ↑ Theodoret, Book 1, Chapter 7

- ↑ Neale, John Mason (2008). A History of the Holy Eastern Church: The Patriarchate of Antioch: The Patriarchate of Antioch. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781606083307.

- ↑ Markessini, Joan (2012). Around the World of Orthodox Christianity - Five Hundred Million Strong: The Unifying Aesthetic Beauty. Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 9781434914866.

- ↑ From the common declaration of Pope John Paul II and Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, 23 June 1984

- ↑ "Psalm 119:164 Seven times a day I praise you for your righteous laws". Bible.cc. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Beth Gazo D-ne`motho http://sor.cua.edu/bethgazo

- ↑ Brock, Sebastian P. The Bible in Syriac Bible. Kottayam: SEERI.

- ↑ Corepiscopos, Kuriakose M. A Guide to the Altar Assistants. Changanacherry: Mor Adai Study Center, 2005.

- ↑ Detailed explanation of vestments of Syriac Orthodox Church http://sor.cua.edu/Vestments/index.html

- ↑ Wright, Colin. "A Glossed Page of Aldhelm's 'De Virginitate'". www.bl.uk.

- ↑ Primacy of St. Peter by Mor Athanasius of Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, Malankara Syriac Christian Resources

- ↑ Gall, Timothy L. (ed). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Culture & Daily Life: Vol. 3 – Asia & Oceania. Cleveland, OH: Eastword Publications Development (1998); pg. 720–721.

- 1 2 Murre-van den Berg, Heleen (2011). "Syriac Orthodox Church". In Kurian, George Thomas. The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 2304. ISBN 978-1-4051-5762-9.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld – World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Turkey : Syriacs". Refworld. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ↑ "Adherents.com". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ "Church of the Syrian Christians in India". Wesleyan Juvenile Offering. London: Wesleyan Missionary Society. XII: 115. October 1855. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "SOCNews - The Holy Synod approves the name "Syriac Orthodox Church"". sor.cua.edu.

- ↑ "Antioch Syrian University". asu.edu.sy.

- ↑ "Patriarchate of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch". Archived from the original on 18 April 2008.

- ↑ News Regarding the April 2013 Abductions of Bishops in Syria.

- ↑ "İstanbul - Ankara Süryani Ortodoks Metropolitliği". www.suryanikadim.org.

- ↑ "Reception in the Honor of His Holiness in Brussels". Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch. 7 September 2017.

- ↑ Rabo, Gabriel. "Mor Augin Monastery in Switzerland Consecrated". www.suryoyo.uni-goettingen.de.

- ↑ "Igreja Sirian Ortodoxa de Antioquia no Brasil". Igreja Sirian Ortodoxa de Antioquia no Brasil (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Australia & New Zealand". 22 November 2014.

Sources

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). Syriac Studies: A Classified Bibliography, 1960-1990. Kaslik: Parole de l'Orient.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1997). A Brief Outline of Syriac Literature. Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- European Centre for Law and Justice (2011): The Persecution of Oriental Christians, what answer from Europe?

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syriac Orthodox Church. |

Official websites

Ecumenical relations with the Catholic Church

- Pope Benedict XIV, Allatae Sunt (On the observance of Oriental Rites), Encyclical, 1755

- Addresses of Pope Paul VI and His Holiness Mar Ignatius Jacob III, 1971

- Common Declaration of Pope John Paul II and His Holiness Mar Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, 1984

- Address of John Paul II on Occasion of the Visit to the Catholicos of the Malankarese Syrian Orthodox Church, 1986

- Address of His Holiness Pope Francis to His Holiness Mor Ignatius Aphrem II Syriac orthodox patriarch of Antioch and all the East, 19 June 2015

Media

- Syriac religious TV channel of Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch

- Syriac Liturgy description and photos

- Syriac Music Online