2020 China–India skirmishes

The 2020 China–India skirmishes are part of an ongoing military standoff between China and India. Since 5 May 2020, Chinese and Indian troops have reportedly engaged in aggressive melee, face-offs and skirmishes at locations along the Sino-Indian border, including near the disputed Pangong Lake in Ladakh and the Tibet Autonomous Region, and near the border between Sikkim and the Tibet Autonomous Region. Additional clashes are ongoing at locations in eastern Ladakh along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) that has persisted since the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

In late May, Chinese forces objected to Indian road construction in the Galwan River valley.[20][21] According to Indian sources, melee fighting on 15/16 June 2020 resulted in the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers (including an officer)[22] and casualties among 43 Chinese soldiers (including the death of an officer).[lower-alpha 2][24][16][25] Several news outlets stated that 10 Indian soldiers, including 4 officers, were taken captive and then released by the Chinese on 18 June.[9]

Amid the standoff, India reinforced the region with 12,000 additional workers, who would assist India's Border Roads Organisation in completing the development of Indian infrastructure along the Sino-Indian border.[26][27] [28] Experts have postulated that the standoffs are Chinese pre-emptive measures in responding to the Darbuk–Shyok–DBO Road infrastructure project in Ladakh.[29] The Chinese have also extensively developed their infrastructure in these disputed border regions.[30][31] Another reason is China's territory grabbing technique, also referred to as 'salami slicing', which involves encroaching upon small parts of enemy territory over a large period of time.[32][33] The revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, in August 2019, by the Indian government has also troubled the Chinese.[34] However, India and China have both maintained that there are enough bilateral mechanisms to resolve the situation through quiet diplomacy.[35][36]

Following the Galwan Valley skirmish on 15 June, numerous Indian government officials said that border tensions will not impact trade between India and China despite some Indian campaigns about boycotting Chinese products.[37][38] However, in the following days, various types of action were taken on the economic front including cancellation and additional scrutiny of certain contracts with Chinese firms, and calls were also made to stop the entry of the Chinese into strategic markets in India such as the telecom sector.[39][40][41] Much of this was protest restricted to publicity stunts and social media appeals.[42][43]

Background

People's Republic of China is a territorially revisionist power having land and water disputes with Bhutan, Taiwan, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, North Korea, South Korea, Japan, Nepal and India.[44][45]

The border between China and India is disputed at 20 different locations. Since the 1980s, there have been over 20 rounds of talks between the two countries related to these border issues.[46] A study by the Observer Research Foundation points out that only 1 to 2 percent of border incidents between 2010 and 2014 received any form of media coverage.[46][47] In 2019, India reported over 660 LAC violations and 108 aerial violations by the People's Liberation Army which were significantly higher than the number of incidents in 2018.[48] There is "no publicly available map depicting the Indian version of the LAC," and the Survey of India maps are the only evidence of the official border for India.[49] The Chinese version of the LAC mostly consists of claims in the Ladakh region, but China also claims Arunachal Pradesh in northeast India.[49] In 2013, Indian diplomat Shyam Saran claimed that India had lost 640 km2 (247 sq mi) due to "area denial" by Chinese patrolling,[50] but he later retracted his claims about any loss of territory to Chinese incursion.[51] Despite the disputes, skirmishes, and standoffs, no incidence of gunshots being fired has been reported between the two countries along the border for over 50 years.[52]

During Chinese paramount leader Xi Jinping's[6] visit to New Delhi in September 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi discussed the boundary question and urged his counterpart for a solution. Modi also argued that the clarification of the border issues would help the two countries to "realise the potential of our relations".[53] However, in 2017, China and India got into a major standoff in Doklam that lasted 73 days.[54][55] China has since increased its military presence in the Tibetan Plateau, bringing in Type 15 tanks, Harbin Z-20 helicopters, CAIG Wing Loong II UAVs and PCL-181 self-propelled howitzers.[lower-alpha 3][56] China also stationed new Shenyang J-16s and J-11s fighter jets at the Ngari Gunsa Airport, which is 200 kilometres (124 mi) from Pangong Tso, Ladakh.[56][30] China has also been increasing its footprint with India's neighbours – Nepal, Sri Lanka and Pakistan; so from India having a monopoly in the region, China is now posing a direct challenge to New Delhi's influence in South Asia.[57]

Causes

Multiple reasons have been cited as the trigger for these skirmishes. One reason stated by American observers is Chinese land grabbing involving encroaching upon small parts of enemy territory over a large period, a tactic also referred to as salami slicing.[32][33] In mid-June 2020, Bharatiya Janata Party councillor Urgain Chodon from Nyoma, Ladakh, stated that successive Indian governments (including the current Narendra Modi government) have neglected the border areas for decades and turned a 'blind-eye' to Chinese land grabbing in the region. According to her India has failed miserably in the protection of its borders and even this year all along the LAC India has lost land, with her family having lost grazing land to the Chinese in Koyal.[58][59] Other local Ladakhi leaders have also acknowledged similar incursions by the Chinese in the region.[60]

On land, for the sake of grabbing territory, the PLA appears to have instigated the most violent clash between China and India since those nations went to war in 1962

MIT professor, Taylor Fravel, said that the skirmishes were a response from China to the development of Indian infrastructure in Ladakh, particularly the Darbuk–Shyok–DBO Road. He added that it was a show of strength for China amidst the COVID-19 pandemic which had damaged the Chinese economy and its international reputation.[61] Lobsang Sangay, President of the Tibetan-government-in-exile, stated that China is raising border issues due to internal problems within China and the international pressure being exerted on China over COVID-19.[62][63] Jayadeva Ranade, President of the Centre for China Analysis and Strategy and former National Security Advisory Board member, posited that China's current aggression in the region is to protects it's assets and future plans in Ladakh and adjoining regions such as the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor; as such Chinese troops are not going to withdraw.[64]

Wang Shida of China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations linked the current border tensions to India's decision to abrogate Article 370 and change the status of Jammu and Kashmir in 2019.[34] Although, Pravin Sawhney agreed with Wang, he postulated that a parliamentary speech by Amit Shah also could have irked the Chinese. In the speech, Shah had declared that Aksai Chin was part of the Ladakh Union Territory.[65] Furthermore, the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir in 2019 prompted multiple senior Bharatiya Janta Party ministers, most recently in May 2020, to claim that all that now remained was for India to regain Gilgit-Baltistan.[66] Indian diplomat Gautam Bambawale also stated that New Delhi's moves in August 2019 related to Jammu and Kashmir irked Beijing.[66] In 2014, Rajnath Singh, the then Home Minister of India, the Defence Minister during the 2020 skirmishes, had said that 'China has illegally occupied Aksai Chin in Ladakh'.[67]

India's former ambassador to China, Ashok Kantha said that these skirmishes were part of a growing Chinese assertiveness in both the Indo-China border and the South China sea.[61] Indian diplomat Phunchok Stobdan pointed to the occurrence of a larger strategic shift and that India should be alert.[68] Retired Indian Army Lt. Gen. Syed Ata Hasnain said that the skirmishes were post–COVID strategic messages from China to its neighbours which would make India prioritize the Himalayan sector over the maritime Indian Ocean region, a more vulnerable area for the Chinese.[69] Raja Mohan, Director of the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, writes that the growing power imbalance between China and India is the main cause of the dispute, with everything else such as the location of the dispute or international ties of India, being mere detail.[70] These skirmishes have also been linked with the Chinese strategy of Five Fingers of Tibet by Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury (leader of the principal opposition party Indian National Congress in the Lok Sabha),[71] Seshadri Chari (former head of the foreign affairs cell of the ruling Bharatiya Janata party),[72] and Lobsang Sangay (leader of the Central Tibetan Administration).[73]

Incidents

There have been simultaneous efforts by China to occupy land at multiple locations along the Sino-Indian border. Locations where the standoffs and skirmishes have taken place are Pangong Tso, Hot Springs, Galwan Valley and Depsang in Ladakh; and in Sikkim as well.[74]

Pangong Tso

|

with "fingers" – mountain spurs jutting into the lake[76] |

On 5 May, the first standoff began as a clash between Indian and Chinese soldiers at a beach of Pangong Tso, a lake shared between India and Tibet, China, with the Line of Actual Control (LAC) passing through it.[77][78] A video showed soldiers from both nations engaging in fistfights and stone-pelting along the LAC.[79] On 10/11 May, another clash took place.[80] A number of soldiers on both sides had sustained injuries. Indian media reported that around 72 Indian soldiers were injured in the confrontation at Pangong Tso, and some had to be flown to hospitals in Leh, Chandi Mandir and Delhi.[81] According to The Daily Telegraph and other sources, China captured 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi) of Indian-patrolled territory between May and June 2020.[82][83][84]

After the clash, several Chinese military helicopters were spotted flying near the Indian border on at least two occasions. India deployed several Sukhoi Su-30MKI jets to the area. Reports that Chinese helicopters had repeatedly violated Indian airspace were denied by the Indian government.[85][86] There were reports of Chinese soldiers approaching Indian soldiers with improvised weaponry of barbed wire "sticks".[87] By 27 June, the Chinese were reported to have increased military presence on both the northern and southern banks of Pangong Tso, strengthened their positions near Finger 4 (contrary to what the status quo was in April), and had even started construction of a helipad, bunkers and pillboxes.[88]

Sikkim

According to Indian media reports, on 10 May, a spat began when the Chinese intruded into the Muguthang Valley and shouted at the Indian troops: "this is not your land. This is not Indian territory ... so, just go back." An Indian lieutenant responded by punching a Chinese major's nose.[89] The incident developed into a brawl involving 150 soldiers, with opposing sides throwing stones at one another.[54] Seven Chinese and four Indian soldiers were reported to have been injured.[18][90][91] Following the incident, the Indian Army withdrew from the front line the Indian lieutenant that initiated the brawl.[80] A spokesperson from Indian Army's Eastern Command said that the matter had been "resolved after 'dialogue and interaction' at a local level" and that "temporary and short-duration face-offs between border guards do occur as boundaries are not resolved. Troops usually resolve such issues by using mutually established protocols".[54][55] China did not share details about the incident, and the Chinese Ministry of Defense did not comment on the incident.[92] However, the foreign ministry said that the "Chinese soldiers had always upheld peace and tranquillity along the border".[92]

Eastern Ladakh

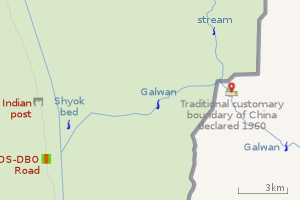

|

(and the traditional customary boundary of China declared 1960).[93] |

On 21 May, the Indian Express reported that Chinese troops had entered the Indian territory in the Galwan River valley and objected to the road construction by India within the (undisputed) Indian territory. The road under construction is a branch of the Darbuk–Shyok–DBO Road (DSDBO) which leads into the Galwan valley.[lower-alpha 5] The report also stated that "the Chinese pitched 70–80 tents in the area and then reinforced the area with troops, heavy vehicles, and monitoring equipment. These all happened not very far from the Indian side."[94] On 24 May, another report said that the Chinese soldiers invaded India at three different places: Hot Springs, Patrol Point 14, and Patrol Point 15. At each of these places, around 800–1,000 Chinese soldiers reportedly crossed the border and settled at a place about 2–3 km (1–2 mi) from the border. They also pitched tents and deployed heavy vehicles and monitoring equipment. The report added that India also deployed troops in the area and stationed them 300–500 metres (984–1,640 ft) from the Chinese.[20][21] According to Indian defence analyst Ajai Shukla, China captured 60 km2 (23 sq mi) of Indian-patrolled territory between May and June 2020.[84][95] According to The Daily Telegraph, China captured 20 km2 (7.7 sq mi) of Indian-patrolled territory in the Galwan valley.[82] According to EurAsian Times, the Chinese have a huge build-up including military-style bunkers, new permanent structures, military trucks, and road-building equipment. It quoted an Indian official who called it "the most dangerous situation since 1962."[96] An official, quoted by The Hindu, stated that "this amounted to a change in the status quo which would never be accepted by India."[97] On 30 May, the Business Standard reported that thousands of Chinese soldiers were "consolidating their positions and digging defences needed to repel Indian attacks." They also reported that there were about 18 guns at Pangong Tso and about 12 guns in the Galwan valley providing fire support for the Chinese. Indian troops had taken up positions to block any further advance by the PLA towards the Darbuk–Shyok–DBO Road.[98]

The Global Times, which is owned by the Chinese government, blamed India for the stand-offs and claimed that India had "illegally constructed defence facilities across the border into Chinese territory in the Galwan Valley region." Long Xingchun, a senior research fellow at the Beijing Foreign Studies University, wrote that the border friction was "an accident". India is definitely aware that the Galwan Valley region is in Chinese territory."[99] On 26 May, paramount leader Xi Jinping[6] urged the military "to prepare for the worst-case scenarios" and "to scale up battle preparedness." Furthermore, he said that the COVID-19 pandemic had brought a profound change on the global landscape about China's security and development.[99] On the same day, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi reviewed the current situation in Ladakh with the National Security Adviser, Ajit Doval and the Chief of Defence Staff, Bipin Rawat.[100] On 27 May 2020, the Chinese Ambassador to India as well as a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman stated that the overall situation was stable.[101] However, news reports continued stating that thousands of Chinese soldiers were moving into the disputed regions in Ladakh. This move prompted India to deploy several infantry battalions from the Leh, the provincial capital of Ladakh and some other units from Kashmir.[102][103]

Hot Springs

Chinese infrastructure development in Hot Springs is mainly in and around Gogra. Tracks in satellite imagery suggest that PLA troops make forays into Indian territory here.[104] A road also connects this area to the Chinese habitat of Wenquan.[104] Hot Springs area is supposed to be rich in minerals such as gold.[105]

Galwan Valley skirmish

|

On 15 June, Indian and Chinese troops clashed for six hours in a steep section of a mountainous region in the Galwan Valley. The immediate cause of the incident is unknown with both sides releasing contradictory official statements in the aftermath.[106] Beijing said that Indian troops had attacked Chinese troops first[107] while on 18 June The Hindu quoted a "senior government official" in the Ministry of External Affairs of India who said their troops were ambushed with dammed rivulets being released and boulders being thrown by Chinese troops.[108] The statement said this happened while they were patrolling a disputed area where Colonel Santosh Babu had destroyed a Chinese tent two days earlier.[108] While soldiers carry firearms, due to decades of tradition designed to reduce the possibility of an escalation, agreements disallow usage of firearms, but the Chinese side is reported to possess iron rods and clubs.[109] As a result, hand-to-hand combat broke out, and the Indians called for reinforcements from a post about 2 miles (3.2 km) away. Eventually, up to 600 men were engaged in combat using stones, batons, iron rods, and other makeshift weapons. The fighting, which took place in near-total darkness, lasted for up to six hours.[110] According to senior Indian military officers, Chinese troops used batons wrapped in barbed wire and clubs embedded with nails.[111]

The fighting resulted in the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers of 16th Bihar Regiment including its commanding officer, Colonel Santosh Babu.[112][113] While three Indian soldiers died on the spot, others died later due to injuries and hypothermia.[114] Most of the soldiers who were killed fell to their deaths after losing their footing or being pushed off the ridge.[110] The clash took place near the fast-flowing Galwan River, and some soldiers from both sides fell into a rivulet and were killed or injured.[114] Bodies were later recovered from the Shyok River.[113] Some Indian soldiers had also been momentarily taken captive.[114] According to Indian media sources, the mêlée resulted in 43 Chinese casualties.[22][115] At a de-escalation meeting following the incident, the Chinese side accepted that the Chinese commanding officer was also killed in the mêlée.[24][116] The Chinese defence ministry confirmed the existence of Chinese casualties but refused to share the number.[117] Later on, when asked about an Indian minister's assertion about the number of Chinese casualties, China refused to comment.[118] U.S. intelligence reportedly concluded that 35 Chinese soldiers were killed.[19][119] Indian media reported that 10 Indian soldiers were released from Chinese custody in 17 June, including four officers.[9][120] Responding to the reports, the Indian army and the Chinese foreign ministry have both denied that any Indian personnel was taken into custody.[121]

On 16 June, Chinese Colonel Zhang Shuili, spokesperson for the PLA's Western Command, said that the Indian military violated bilateral consensus. He further remarked that "the sovereignty over the Galwan Valley area had always belonged to China".[113][122][123] On 18 June, India's Minister of External Affairs, S. Jaishankar made a statement saying that China had "unilaterally tried to change the status quo" and that its claims over the Galwan Valley were "exaggerated and untenable" and the violence was "premeditated and planned".[124][125] The same day, US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs David Stilwell said that the Chinese PLA had "invaded" the "contested area" between India and China.[126] On 19 June, however, Prime Minister Modi declared that "neither have they (China) intruded into our border, nor has any post been taken over by them", contradicting multiple previous statements by the Indian government.[106][127] Later the Prime Minister's Office clarified that Narendra Modi wanted to indicate the bravery of 16 Bihar Regiment who had foiled the attempt of the Chinese side.[128][129] On 22 June, U.S. News & World Report reported that U.S. intelligence agencies have assessed that the chief of China's Western Theater Command had sanctioned the skirmish.[130]

In the aftermath of the incident at Galwan in which the Chinese used nailed-spiked rods, the Indian Army decided to equip soldiers along the border with lightweight riot gear as well as spiked clubs.[131][132] The Indian Air Force also started the process for emergency procurement of 12 Sukhoi-30 MKI and 21 Mikoyan MiG-29 from Russia.[133][134] On 20 June, India removed restriction on usage of firearms for Indian soldiers along the LAC.[135] Satellite images analysed by an Australian Strategic Policy Institute's analysis shows that the Chinese have increased construction in the Galwan valley since the 15 June skirmish.[136] The Chinese post that was destroyed by Indian troops on 15 June was reconstructed by 22 June, with an expansion in size and with more military movement. Other new defensive positions by both Indian and Chinese forces have also been built in Galwan.[137]

Depsang plains

Chinese presence, 18 km (11 mi) inside India's side of the LAC, 30 km (19 mi) south-east of DS-DBO road on the Y-junction or Bottleneck at the Depsang Plains, was reported by Indian media on 25 June 2020, who described movements of troops, heavy vehicles and military equipment. The Chinese claim lines are 5 km further west of bottleneck.[138] Indian Patrol Points (PP) 10, 11, 11A, 12 have been blocked by PLA movement and construction at the bottleneck in Depsang. Analyst Praveen Swami reasoned, if the PLA moves additional troops to Raki river then PP 13 is also cut off. China will have claimed more Indian territory.[139] However, Indrani Bagchi, diplomatic editor for The Times of India, described the military buildup of the Chinese in and around Depsang are mere diversionary tactics.[140]

Ongoing construction of Indian infrastructure

Amid the standoff, India decided to move an additional 12,000 workers (approximately) to border regions to help complete Indian road projects.[26][27] Around 8,000 workers would help Border Roads Organisation's (BRO) infrastructure project, Project Vijayak, in Ladakh while some workers would also be allocated to other nearby border areas.[141] The workers would reach Ladakh between 15 June and 5 July.[28] The first train with over 1600 workers left Jharkhand on 14 June 2020 for Udhampur, and from there the workers went on to assist BRO at the Sino-Indian border.[28][142] Apart from completing the DS–DBO Road the workers would also be assisting the BRO in the construction of the following roads: "Phobrang–Masmikla road, Masmikla–Hot Springs road, Chisumle–Demchok road, Koyul–Photile–Chisumle–Zurasar road and Hanle–Photile road."[143] Starting from June, the government announced up to 170% increase in minimum wages for those working along the India-China border, with the highest increase in wages going to employees in Ladakh.[144] Experts state that the development of Indian infrastructure along the border was one of the causes for the standoffs.[29]

Diplomatic response

After the first melee took place, on 5–6 May 2020 at Pangong Tso, Foreign Secretary of India Harsh Vardhan Shringla called Sun Weidong, the Chinese ambassador to India.[145] Then, Ajit Doval has reportedly talked to the CCP Politburo member, Yang Jiechi, who is also a top diplomat under CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping.[145] On 28 May, in a press conference, Indian spokesperson for the Ministry of External Affairs, Anurag Srivastava, maintained that there were enough bilateral mechanisms to solve border disputes diplomatically.[146][35] These agreements encompass:[146]

Five bilateral treaties between India and China to address border disputes

- 1993: Agreement on the maintenance of peace and tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the Sino-Indian Border

- 1996: Agreement between the Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the People's Republic of China on confidence-building Measures in the military field along the Line of Actual Control in the Sino-Indian Border

- 2005: Protocol on the modalities for the implementation of confidence-building measures in the military field along the Line of Actual Control in the Sino-Indian Border

- 2012: Establishment of a working mechanism for consultation and coordination on Sino-Indian border affairs

- 2013: Border defense cooperation agreement between India and China

Additionally there are other agreements related to the border question such as the 2005 "Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question".[147][148] However, some critics say that these agreements are "deeply flawed".[149] The Border personnel meeting (BPM) points have seen rounds of military talks in May–June; first between colonels, then between brigadiers, and then finally, on 2 June, more than three rounds between major generals.[150][151] All these talks were unsuccessful. Some Indian military sources said that India was still unclear with China's demands. "When one wants to stall a process, one makes absurd demands...they purposefully made some unreasonable demands", said the sources.[150] On 6 June 2020, lieutenant general-level talks took place between India and China in Chushul-Moldo.[150][152] The talks involved the Indian commander of Leh-headquartered XIV Corps and the Chinese commander of the Tibet Military District (South Xinjiang Military Region) Maj Gen Liu Lin.[153][152] Prior to talks on 6 June 2016, at lieutenant general-level, the Global Times warned India over American ties.[154]

Following the Galwan clash Chinese flags and effigies of paramount leader Xi Jinping were set afire in various places across India and various groups registered their protests in different ways. The Global Times responded to these protests saying that it is "extremely dangerous for India to allow anti-China groups to stir public opinion".[155][156] On 17 June 2020, Prime Minister Modi addressed the nation regarding the Galwan skirmish, giving a firm message directed at China over the deaths of Indian soldiers.[157][158] The first communication, since the start of the border dispute, between the foreign ministers of China, Wang Yi and of India, S Jaishankar also happened post Galwan skirmish.[157] S Jaishankar accused the Chinese actions in Galwan to be "pre-meditated and planned".[157] On 20 June, Chinese social media platform WeChat removed the Indian Prime Minister's remarks on the Galwan skirmish,[159] which was uploaded by the Indian Embassy in China. The official statements of the Ministry of External Affairs were also removed. WeChat said that it removed the speech and statements because they divulged in state secrets and endangered national security.[160] The MEA spokesperson's statement on the incident was also removed from Weibo. Following this, the Indian embassy in China issued a clarification on its Weibo account that the post wasn't removed by them, and re-published a screenshot of the statement in Chinese.[161]

The second round of commanders meeting was on 22 June. In an 11-hour meeting, the commanders worked out a disengagement outline. On 24 June this disengagement was then diplomatically acknowledged by both sides during the virtual meeting of the "Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on China-India Border Affairs".[136] Chinese spokesperson Zhao Lijian said that India "agreed to and withdrew its cross-border personnel in the Galvan Valley and dismantled the crossing facilities in accordance with China's request".[136][162]

Economic response

Initially, India's economic response to China was mainly restricted to patriotic programs on news channels and social media publicity appeals, with very little actual impact on businesses and sales.[42] In May, in response to the border skirmishes, Sonam Wangchuk appealed to Indians to use "wallet power" and boycott Chinese products.[164] This appeal was covered by major media houses and supported by various celebrities.[164][165] Following the Galwan Valley clash on 15 June 2020, there were calls across India to boycott Chinese goods.[38][166] The Indian Railways cancelled a contract with a Chinese firm, while the Department of Telecommunication notified BSNL not to use any Chinese made product in upgradations.[41] Mumbai cancelled a monorail contract where the only bidders were Chinese companies; and alternatively said it would focus on finding an Indian technological partner instead.[167] Numerous Chinese contractors and firms were under enhanced scrutiny following the 2020 border friction. Chinese imports are going through additional checks at Indian customs.[168] (In retaliation, customs in China and Honk Kong held up Indian exports).[169] There are also calls for making sure the Chinese do not have access to strategic markets in India.[39] Swadeshi Jagaran Manch said that if the government was serious about making India self-reliant, Chinese companies should not be given projects such as the Delhi-Meerut RRTS.[40][170] The Haryana government cancelled a tender related to a power project in which Chinese firms had put in bid.[171] The Uttar Pradesh government Special Task Force personnel were given orders to delete 52 apps including TikTok and WeChat for security reasons while officials in Madhya Pradesh Police were given an advisory for the same.[172][173]

Numerous Indian government officials said that border tensions would have no impact on trade between the two countries.[37] Amid the increased visibility of calls for boycotting Chinese goods in the aftermath of the Galwan incidents, numerous industry analysts warned that a boycott would be counter-productive for India, would send out the wrong message to trade partners, and would have very limited impact on China, since both bilaterally as well as globally India is comparatively a much smaller trade power.[174][175][176][177] Experts also stated that while the boycott campaign was a good initiative, replacement products should be available in the immediate future too.[178] An example taken was the pharmaceutical industry in India which meets 70% of its active pharmaceutical ingredient requirements from China. Dumping in this sector is being scrutinized.[179][180] By the end of June, some analysts agreed that the border tensions between India and China would give the Make in India campaign a boost and increase the pace of achieving self-reliance in some sectors.[178] On 21 June 2020, the Global Times wrote in an opinion piece:[181]

Nationalist fever is being fueled. For instance, retired Indian army officer Ranjit Singh told Indians last week to throw Chinese goods out, asserting Indians "can break China's backbone economically". We hope Indian people won't be fooled by the radical elements in their country. India needs China, economically and geopolitically [...] Of the top 30 so-called unicorn startup enterprises in India, 18 have Chinese investments.[lower-alpha 6] And many daily necessities enjoyed by Indians [...] are produced by China. With both affordable prices and good quality, Chinese items are difficult to replace. It seems that extreme nationalist forces in India are again stirring up the "Boycott Made-in-China" message to vent their anger. But they need to look at what they have at home [...] Some claim that they could offload their 4G mobile networks to be replaced with equipment made in India, but in reality, until today there has not been a single Indian telecom maker that is able to manufacture 3G and 4G gears.[181]

The issue of Chinese materials in Indian Army bulletproof vests was again raised in June after the Galwan incidents.[183] A NITI Aayog member said that, it was due to the quality and the pricing that Chinese material was being used instead of Indian products.[184] Bullet-proof vests ordered by the government in 2019 had up to 40% Chinese material. On 20 June 2020, it was reported that development of an Indian bulletproof vest, the "Sarvatra Kavach", that is 100% made in India, is near completion.[185] The Maharashtra government put ₹5,000 crore (US$700 million) worth of Chinese projects on hold.[186] The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade brought out a list of over a 1000 Made in China goods on which the Government of India has sought comments for imposing import restrictions. Previously, the Department had asked private companies to submit a list of Chinese imports.[187][188] Incidents in Ladakh are also being taken as additional reasons to keep India away from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in which China has a big role.[189]

Sales of Chinese smartphones in India were not affected in the immediate aftermath of the skirmishes, despite calls for a boycott. The latest model of Chinese smartphone company OnePlus sold out within minutes in India on 18 June 2020, two days after the Galwan clash.[190][191] Xiaomi India's managing director said that the social media backlash would not affect sales, adding that Xiaomi handsets are "more Indian than Indian handset companies" and that even many non-Chinese phones, including American handsets, are made in and imported from China.[43][192] Following this, the Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT), an apex traders body in India, made a statement sharply criticising Xiaomi's managing director saying that he was "trying to please his Chinese masters by downplaying the mood of the nation".[193][194] TTK Prestige, India's largest kitchen appliances maker, said it would stop all imports from China from 30 September 2020 onwards.[195]

Public response in Kashmir and Ladakh

Following Galwan clash on 17 June, former chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Omar Abdullah tweeted, "Those Kashmiris tempted to look towards China as some sort of saviour need only google the plight of Uighur Muslims. Be careful what you wish for...".[196] He deactivated his twitter account following the tweet.[196] Khalid Shah, a Associate fellow at ORF, writes that at large the Kashmiri population has "left no stone unturned to mock the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi for the Chinese belligerence."[197] Stone pelters in Srinagar used slogans such as "cheen aya, cheen aya" (China has arrived, China has arrived) to make fun of the Indian security forces while a joke going around is "cheen kot woat?" (where has China reached?). Memes show Xi Jingping dressed in Kashmiri attire with others showing him cooking wazwan. Khalid writes that while China has become a part of many conversations, online and offline, India should be worried that "Chinese bullying is compared to the actions of the Government of India".[197] Following the tensions with China, communication lines had been cut in Ladakh in places along the border causing a communication blackout, resulting in local councilors requesting the government for the lines to be restored.[198]

International response

- US President Donald Trump, on 27 May 2020, offered to mediate between China and India. This offer was rejected by both countries. The US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo also raised the issue in a podcast, and referring to China said that these were the kind of actions that authoritarian regimes took and that they can have a real impact.[199] Eliot Engel, chief of the US House Foreign Affairs Committee, also expressed concern with the situation. He said that "China was demonstrating once again that it was willing to bully its neighbors".[200] On 2 June, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Donald Trump discussed the Sino-Indian border situation.[201] In the aftermath of Galwan, the US Secretary of State tweeted condolences to the people of India for the lives lost;[202] while the US Department of State said that the situation was being closely watched.[203]

- On 20 June, US President Donald Trump said that the US is in touch with both China and India to assist them in resolving the tensions.[204] On 25 June, Mike Pompeo stated that American troops were being moved out of Germany and are being redeployed in India and other American allied South East Asian countries because of the recent actions by the Communist Party of China and so as to be appropriately positioned to act as a counter to the PLA.[205] Congressman Ted Yoho made a statement on 27 June saying that, "China's actions towards India fall in line with a larger trend of the Communist Party of China using the confusion of the COVID-19 pandemic as a cover to launch large scale military provocations against its neighbours in the region, including Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Vietnam [...] Now is the time for the world to come together and tell China that enough is enough." Congressman Ami Bera also expressed concern over the situation at the Indo-China border.[206]

- Roman Babushkin, the Russian Deputy Chief of Mission in Delhi, stated on 1 June that Russia maintains that the issue should be solved bilaterally between India and China.[207][208] On 2 June, the Foreign Secretary of India updated and discussed the situation with the Russian Ambassador to India, Nikolay R. Kudashev.[209] Following Galwan, on 17 June, the Ambassador of India in Russia spoke to the Russian Deputy Foreign Minister about the situation.[210] Dmitry Peskov, Press Secretary for the President of Russia, said that the situation was being closely watched.[211]

- Russia initiated virtual talks between RIC (Russia–India–China) on 22 June.[212][213] Russia had scheduled the RIC trilateral for March but delayed it due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[212] In relation to the border situation between India and China, Foreign Minister of Russia, Sergey Lavrov said that the topics for the meeting were already been agreed upon and "the RIC agenda does not involve discussing issues that are related to bilateral relations of a country with another member."[214] During the trilateral meeting India reminded Russia and China of India's selfless involvement in the Russian and Chinese interests during the World War II, where India helped both the countries by keeping supply lines opened in the Persian Corridor and over the Himalayan Hump.[215]

- Russia argued that a Sino-Indian confrontation would be a "bad idea" for both the countries, for the Eurasian region and the international system. Russia said such confrontation will damage the Chinese legitimacy in the international system and will reduce the existing limited Chinese soft power. It had advised both the countries that it would be a winnable situation for both the countries with no confrontation while giving the example of zero confrontation of the Soviet Union and the US during the Cold War.[216] Russia also proposed to hold the first meeting of the defence chiefs of the three countries which China and India also agreed during the meeting. However, Russia reiterated that China and India can sort out its differences through bilateral means without the involvement of the third party including Russia.[215]

.svg.png)

Media coverage

Chinese media have given little to no attention to the dispute and have downplayed the clashes. In the first month of the standoff, there was only a single editorial piece in the China Daily and the People's Daily.[223] The People's Daily and the PLA Daily did not cover the Galwan clash while the Global Times (Chinese) carried it on page 16.[224] The state broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV) carried the official military statement on social media with no further coverage.[224] The Global Times ran a number of opinion pieces and one editorial which questioned why China did not disclose its death toll publicly.[224][223][225] However, the Chinese media welcomed Prime Minister Modi's 19 June statement.[106] The Global Times quoted Lin Minwang, a professor at Fudan University's Center for South Asian Studies in Shanghai, as saying that "Modi's remarks will be very helpful to ease the tensions because as the Prime Minister of India, he has removed the moral basis for hardliners to further accuse China".[226]

In India, nearly all mainstream newspapers carried front page stories as well as multi-page stories of the incident.[227] Following the June 15 clash in Galwan, Times Now published a list that it said contained the names of the Chinese soldiers who were killed in the clash; multiple sources said that it was fake news.[228][229][230] Another list reported by Indian media that was said to also show Chinese soldiers who were killed in action was described by Chinese spokesperson Zhao Lijian as fake news.[231] Ahead of the commanders' meeting on 6 June, disinformation campaigns were reportedly run by Chinese state-controlled media as well as corporations. The Chinese broadcasters showed military manoeuvres along the border, reportedly designed to frighten the Indians.[232] TikTok was reported to have given "shadow bans" to videos related to the border tension. Statements from India were removed from Chinese social media companies such as Weibo and WeChat.[233][234][235] Following the Galwan clash, international coverage in The New York Times[236] and The Guardian commented on the "nationalistic" character of the leaders of both countries and the "dangers posed by expansionist nationalism".[237] The BBC described the situation in Galwan as "an extraordinary escalation with rocks and clubs".[238][239]

See also

Notes

- Xi Jinping is holding the positions of the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) and the Chinese President, making him the paramount leader of China. However, the Chinese President is a largely a ceremonial office with limited power and not the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces.[6]

- China tends not to officially release these figures immediately, sometimes even only after decades[23]

- As reported by the Global Times, an affiliate of the People's Daily

- The delineation of boundaries on this map must not be considered authoritative

- The Darbuk–Shyok–DBO Road (DSDBO) is the first border road constructed by India in the Shyok River valley. Started in 2000, it was completed recently in April 2019.

- Though overall Chinese investments in India, including startups, is very low compared to other countries[182]

References

- "Galwan Valley face-off: Indian, Chinese military officials meet to defuse tension". Hindustan Times. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Anirban Bhaumik (18 June 2020). "Galwan Valley: Indian, Chinese diplomats to hold video-conference soon". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "IGP Ladakh reviews security arrangements". Daily Excelsior. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "PLA Death Squads Hunted Down Indian Troops in Galwan in Savage Execution Spree, Say Survivors". News18 India.

- "India, Chinese troops face-off at eastern Ladakh; casualties on both sides". 16 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Li, Nan (26 February 2018). "Party Congress Reshuffle Strengthens Xi's Hold on Central Military Commission". The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

Xi Jinping has introduced major institutional changes to strengthen his control of the PLA in his roles as Party leader and chair of the Central Military Commission (CMC)...

- "The Chinese generals involved in Ladakh standoff". Rediff.com. 13 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Michael Safi and Hannah Ellis-Petersen (16 June 2020). "India says 20 soldiers killed on disputed Himalayan border with China". Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Haidar, Suhasini; Peri, Dinakar (18 June 2020). "Ladakh face-off | Days after clash, China frees 10 Indian soldiers". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "76 Soldiers Brutally Injured in Ladakh Face-off Stable And Recovering, Say Army Officials". Outlook. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "China denies detaining Indian soldiers after reports say 10 freed". Al Jazeera. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Roy, Rajesh (19 June 2020). "China Returns Indian Troops Captured in Deadly Clash". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Meyers, Steven Lee; Abi-Habib, Maria; Gettlemen, Jeffrey (17 June 2020). "In China-India Clash, Two Nationalist Leaders With Little Room to Give". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "India, China skirmishes in Ladakh, Sikkim; many hurt", The Tribune, 10 May 2020

- "China suffered 43 casualties in violent face-off in Galwan Valley, reveal Indian intercepts". Asian News International. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "China suffered 43 casualties during face-off with India in Ladakh: Report". India Today. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "'We also released detained Chinese troops, Patrol Point 14 still under India's control': Union Min VK Singh". Times Now. 20 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Vedika Sud; Ben Westcott (11 May 2020). "Chinese and Indian soldiers engage in 'aggressive' cross-border skirmish". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Paul D. Shinkman (16 June 2020). "India, China Face Off in First Deadly Clash in Decades". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Philip, Snehesh Alex (24 May 2020). "Chinese troops challenge India at multiple locations in eastern Ladakh, standoff continues". The Print. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Singh, Sushant (24 May 2020). "Chinese intrusions at 3 places in Ladakh, Army chief takes stock". The Indian Express.

- "India soldiers killed in clash with Chinese forces". BBC News. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Pita, Adrianna; Madan, Tanvi (18 June 2020). "What's fueling the India-China border skirmish?" (PDF). Brookings. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

We do not know the Chinese casualty numbers - they do not tend to officially release this sometimes for decades, for various reasons...

- "At Talks, China Confirms Commanding Officer Was Killed in Ladakh: Sources". NDTV.com. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Commanding Officer of Chinese Unit among those killed in face-off with Indian troops in Galwan Valley". Asian News International. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Singh, Rahul; Choudhury, Sunetra (31 May 2020). "Amid Ladakh standoff, 12,000 workers to be moved to complete projects near China border". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Amid border tension, India sends out a strong message to China". Deccan Herald. 1 June 2020. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Kumar, Rajesh (14 June 2020). "CM flags off train with 1,600 workers for border projects | Ranchi News". The Times of India. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Indian border infrastructure or Chinese assertiveness? Experts dissect what triggered China border moves". The Indian Express. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "China starts construction activities near Pangong Lake amid border tensions with India". Business Today (India). 27 May 2020. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Desai, Shweta (3 June 2020). "Beyond Ladakh: Here's how China is scaling up its assets along the India-Tibet frontier". Newslaundry. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "China's 'salami-slicing tactics' displays disregard for India's efforts at peace". Hindustan Times. 6 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Chinese Army May Have Provoked Clash To 'Grab Indian Territory': US Senator". NDTV. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Krishnan, Ananth (12 June 2020). "Beijing think-tank links scrapping of Article 370 to LAC tensions". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy (29 May 2020). "India-China activate 5 pacts to defuse LAC tensions". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Roche, Elizabeth (8 June 2020). "India, China to continue quiet diplomacy on border dispute". LiveMint.com. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Suneja, Kirtika; Agarwal, Surabhi (17 June 2020). "Is This Hindi-Chini Bye Bye on Trade Front? Maybe Not: No immediate impact likely on business relations, say govt officials" (print version). The Economic Times.

- Pandey, Neelam (16 June 2020). "Traders' body calls for boycott of 3,000 Chinese products over 'continued' border clashes". ThePrint. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Ninan, T. N. (20 June 2020). "To hit China, aim carefully. Don't shoot yourself in the foot". ThePrint. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Arnimesh, Shanker (15 June 2020). "RSS affiliate wants Modi govt to cancel Chinese firm's bid for Delhi-Meerut RRTS project". ThePrint. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Dastidar, Avishek G; Tiwari, Ravish (18 June 2020). "Chinese firms to lose India business in Railways, telecom". The Indian Express. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Taskin, Bismee (18 June 2020). "Breaking TV sets to boycotting Chinese goods – India's RWAs wage 'war' against Xi's China". ThePrint. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Anti-China sentiment may not hit business; Xiaomi India MD tells why". Business Today. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Gupta, Shishir (20 June 2020). "Not just India's Galwan, China has a long list of territorial disputes". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Sitaraman, Srini (9 June 2020). "China's Salami Slicing Tactics and The Latest India-China Border Standoff". Security Nexus. Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. 21 - 2020.

- Ladwig, Walter (21 May 2020). "Not the 'Spirit of Wuhan': Skirmishes Between India and China". Royal United Services Institute. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Bhonsale, Mihir (12 February 2018). "Understanding Sino-Indian border issues: An analysis of incidents reported in the Indian media". Observer Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Smith, Jeff M. (13 June 2020). "The Simmering Boundary: A "new normal" at the India–China border? | Part 1". ORF. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Singh, Sushant (2 June 2020). "Line of Actual Control: Where it is located, and where India and China differ". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Stobdan, P (26 May 2020). "As China intrudes across LAC, India must be alert to a larger strategic shift". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Shyam Saran: Shyam Saran denies any report on Chinese incursions". The Times of India. 6 September 2013. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Lau, Staurt (6 July 2017). "How a strip of road led to China, India's worst stand-off in years". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Lt Gen Vinod Bhatia (2016). China's Infrastructure in Tibet And Pok – Implications And Options For India (PDF) (Report). Centre for Joint Warfare Studies, New Delhi.

- France-Presse, Agence (11 May 2020). "Indian and Chinese soldiers injured in cross-border fistfight, says Delhi". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Som, Vishnu (10 May 2020). Sanyal, Anindita (ed.). "India, China troops clash in Sikkim, pull back after dialogue". NDTV. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Chan, Minnie (4 June 2020). "China flexing military muscle in border dispute with India". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Abi-Habib, Maria (19 June 2020). "Will India Side With the West Against China? A Test Is at Hand". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Wallen, Joe (24 June 2020). "Modi is standing aside as China seizes our land, says furious BJP politician from border region". The Telegraph. Yahoo News. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Rashid, Hakeem Irfan (24 June 2020). "Successive govts have neglected border areas of Ladakh: Nyoma's BDC chair". The Economic Times. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Dasgupta, Sravasti (28 June 2020). "Flagging Chinese incursions for long, Galwan flare-up was waiting to happen: Ladakh leaders". ThePrint. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Singh, Sushant (26 May 2020). "Indian border infrastructure or Chinese assertiveness? Experts dissect what triggered China border moves". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020.

- "China raking border issue to curb internal issues, COVID-19 paranoia: Lobsang Sangay". The Statesman. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "LAC stand-off will go on unless Tibet issue is resolved, says exiled govt". Hindustan Times. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Sreevatsan, Ajai (18 June 2020). "Beijing is not going to withdraw its soldiers: Jayadeva Ranade". Livemint. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Sawhney, Pravin (10 June 2020). "Here's Why All's Not Well for India on the Ladakh Front". The Wire. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Wahid, Siddiq (11 June 2020). "There is a Global Dimension to the India-China Confrontation in Ladakh". The Wire. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "China has illegally occupied Aksai Chin: Rajnath". Hindustan Times. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Stobdan, Phunchok (26 May 2020). "As China intrudes across LAC, India must be alert to a larger strategic shift". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Action on the LAC | Blitzkrieg with Major Gaurav Arya. Republic TV. 6 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Raja Mohan (9 June 2020). "China now has the military power to alter territorial status quo". The Indian Express. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Chowdhury, Adhir Ranjan (17 June 2020). "Chinese intrusion in Ladakh has created a challenge that must be met". The Indian Express. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Chari, Seshadri (12 June 2020). "70 yrs on, India's Tibet dilemma remains. But 4 ways Modi can achieve what Nehru couldn't". ThePrint. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Siddiqui, Maha (18 June 2020). "Ladakh is the First Finger, China is Coming After All Five: Tibet Chief's Warning to India". CNN-News18. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Tellis, Ashley J. (June 2020). "Hustling in the Himalayas: The Sino-Indian Border Confrontation" (PDF). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

-

India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press, Chinese Report, Part 1 (PDF) (Report). pp. 4–5.

The location and terrain features of this traditional customary boundary line are now described as follows in three sectors, western, middle and eastern. ... From Ane Pass southwards, the boundary line runs along the mountain ridge and passes through peak 6,127 (approximately 78° 46' E, 38° 50' N) [sic] and then southwards to the northern bank of the Pangong Lake' (approximately 78° 49' E, 33° 44' N). It crosses this lake and reaches its southern bank at approximately 78° 43' E, 33° 40' N. Then it goes in a south-easterly direction along the watershed dividing the Tongada River and the streams flowing into the Spanggur Lake until it reaches Mount Sajum. - Lt Gen HS Panag (Retd) (4 June 2020). "India's Fingers have come under Chinese boots. Denial won't help us". The Print.

- "India and China face off along disputed Himalayan border". The Nikkei. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Singh, Sushant (22 May 2020). "India-China conflict in Ladakh: The importance of Pangong Tso lake". The Indian Express. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "'All-out combat' feared as India, China engage in border standoff". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Bhaumik, Subir (11 May 2020). "Sikkim & Ladakh face-offs: China ups ante along India-Tibet border". The Quint. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Roy, Sukanya (27 May 2020). "All you need to know about India-China stand-off in Ladakh". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Wallen, Joe; Yan, Sophia; Farmer, Ben (12 June 2020). "China annexes 60 square km of India in Ladakh as simmering tensions erupt between two superpowers". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Ajai Shukla (8 June 2020). "China has captured 60 sq km of Indian land!". Rediff. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Biswas, Soutik (16 June 2020). "An extraordinary escalation 'using rocks and clubs'". BBC News. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "Chinese helicopters spotted along Sino-India border in Eastern Ladakh: Sources". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 12 May 2020. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "No airspace violation by China: Govt sources". The Times of India. 12 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "'Unprofessional' Chinese Army used sticks, clubs with barbed wires and stones in face-off near Pangong Tso". The Times of India. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Singh, Sushant (27 June 2020). "Chinese building helipad in Pangong Tso, massing troops on southern bank of lake". The Indian Express. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Bhaumik, Subir (11 May 2020). "Sikkim clash: 'Small' Indian lt who punched a 'big' Chinese major". The Quint. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Army confirms India-China face-off, minor injuries to both sides". Hindustan Times. 10 May 2020. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Peri, Dinakar (10 May 2020). "India, China troops face off at Naku La in Sikkim, several injured". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Patranobis, Sutirtho (11 May 2020). Tripathi, Ashutosh (ed.). "'Should work together, fight Covid-19': China to India after Sikkim face-off". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press, Chinese Report, Part 1 (PDF) (Report). pp. 4–5.

The location and terrain features of this traditional customary boundary line are now described as follows in three sectors, western, middle and eastern. ... The portion between Sinkiang and Ladakh for its entire length runs along the Karakoram Mountain range. Its specific location is as follows: From the Karakoram Pass it runs eastwards along the watershed between the tributaries of the Yarkand River on the one hand and the Shyok River on the other to a point approximately 78° 05' E, 35° 33' N, turns southwestwards and runs along a gully to approximately 78° 01' E, 35° 21' N; where it crosses the Chipchap River. It then turns south-east along the mountain ridge and passes through peak 6,845 (approximately 78° 12' E, 34° 57' N) and peak 6,598 (approximately 78° 13' E, 34° 54' N). From peak 6,598 it runs along the mountain ridge southwards until it crosses the Galwan River at approximately 78° 13' E, 34° 46' N. Thence it passes through peak 6,556 (approximately 78° 26' E, 34° 32' N), and runs along the watershed between the Kugrang Tsangpo River and its tributary the Changlung River to approximately 78° 53' E, 34° 22' N. where it crosses the Changlung River. - Singh, Sushant (21 May 2020). "India builds road north of Ladakh lake, China warns of 'necessary counter-measures'". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Ajai Shukla (8 June 2020). "China has captured 60 sq km of Indian land!". Rediff. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Ticku, Nitin J. (24 May 2020). "India, China Border Dispute in Ladakh as Dangerous as 1999 Kargil Incursions – Experts". EurAsian Times.

- Peri, Dinakar (25 May 2020). "Deliberations on to resolve LAC tensions". The Hindu.

- Shukla, Ajai (30 May 2020). "Defence minister Rajnath Singh speaks to US on China's LAC intrusion". Business Standard.

- Krishnan, Ananth (26 May 2020). "Chinese President Xi Jinping meets PLA, urges battle preparedness". The Hindu.

- Peri, Dinakar (26 May 2020). "India-China LAC standoff | Narendra Modi reviews situation with NSA, CDS and 3 Service Chiefs". The Hindu.

- "'Differences Should Not Overshadow Relations': China Downplays Border Standoff, Says Situation Controllable". News18. 27 May 2020. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "China and India move troops as border tensions escalate". The Guardian. 27 May 2020.

- "Army Sends Reinforcements from Kashmir to Ladakh as China Tries to Bully India Amid Cold War With US". News18. 1 June 2020.

- Ruser, Nathan (18 June 2020). "Satellite images show positions surrounding deadly China–India clash". The Strategist. Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Pubby, Manu (1 June 2020). "Amid standoff, China builds road to mineral rich area". The Economic Times. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "'China did not enter our territory, no posts taken': PM at all-party meet on Ladakh clash". Hindustan Times. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Agencies (17 June 2020). "China blames Indian troops for deadly border clash". DAWN. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Singh, Vijaita (18 June 2020). "Ladakh face-off: China's People's Liberation Army meticulously planned attack in Galwan, says senior government official". The Hindu. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Tripathi, Ashutosh, ed. (18 June 2020). "'All border troops carry arms': Jaishankar responds to Rahul Gandhi on Ladakh standoff". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Safi, Michael; Ellis-Petersen, Hannah; Davidson, Helen (17 June 2020). "Soldiers fell to their deaths as India and China's troops fought with rocks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Haltiwanger, John (18 June 2020). "Hundreds of Chinese troops reportedly hunted down dozens of Indian soldiers and beat them with batons wrapped in barbed wire". Business Insider. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Peri, Dinakar; Krishnan, Ananth (16 June 2020). "India-China standoff | Army officer, two jawans killed in Ladakh scuffle; casualties on Chinese side also". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Pubby, Manu (17 June 2020). "Over 20 soldiers, including Commanding Officer killed at Galwan border clash with China". The Economic Times. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Pandit, Rajat (17 June 2020). "LAC standoff: 20 Indian Army soldiers die in worst China clash in 53 years | India News". The Times of India. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Ghosh, Deepshikha, ed. (16 June 2020). "Updates: 20 Indian Soldiers Killed; 43 Chinese Casualties In Ladakh, Says ANI". Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Commanding Officer of Chinese Unit among those killed in face-off with Indian troops in Galwan Valley". Asian News International. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "China State Media Plays Down India Clash, No Mention Of Casualties". NDTV.com.

- Service, Tribune News. "China declines to react to VK Singh's remark that 40 PLA soldiers killed in Galwan Valley clash". The Tribune. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "China India clashes: China suffered 35 casualties during Galwan clash: US intelligence reports | India News". The Times of India.

- Singh, Sushant (19 June 2020). "Hectic negotiations lead to return of 10 Indian soldiers from Chinese custody". The Indian Express. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "China denies detaining Indian soldiers after reports say 10 freed". Al Jazeera. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Chinese military demands Indian border troops stop infringing and provocative actions". Ministry of National Defense of the People's Republic of China. China Military Online. 16 June 2020.

- Khaliq, Riyaz ul (16 June 2020). "Indian troops violated agreements along LAC: China". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "'Exaggerated': India's late night rebuttal to China's new claim over Galwan Valley". Hindustan Times. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Haidar, Suhasini (17 June 2020). "Chinese troops tried to change status quo: India". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Jones, Keith. "US stokes India-China conflict, blames Chinese "aggression" for border clash". wsws.org. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Modi's 'No Intrusion' by China Claim Contradicts India's Stand, Raises Multiple Questions". The Wire. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "PMO issues clarification over Modi's comments that no one entered Indian territory". Time of India. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "PMO issues clarification over Modi's comments that no one entered Indian territory". The Economic Times. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Shinkman, Paul D. (22 June 2020). "U.S. Intel: China Ordered Attack on Indian Troops in Galwan River Valley". U.S. News & World Report.

- "India recovers from the shock of nail-studded clubs, gets ready to get even". The Economic Times. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Unnithan, Sandeep (18 June 2020). "A new arms race?". India Today. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Negi, Manjeet Singh (18 June 2020). "India to buy 12 Sukhoi, 21 MiG-29s amid India-China standoff". India Today. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Indian Air Force plans to buy 12 Sukhoi, 21 MiG-29s amid India-China standoff". Business Today. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Singh, Rahul (20 June 2020). "'No restrictions on using firearms': India gives soldiers freedom along LAC in extraordinary times". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "China Ups Rhetoric, Warns India of 'Severe Consequences' for Violent Clash". The Wire. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Ladakh face-off | Destroyed Chinese post back in Galwan Valley". The Hindu. Special Correspondent. 24 June 2020. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 25 June 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Singh, Sushant (25 June 2020). "Closer to strategic DBO, China opens new front at Depsang". The Indian Express. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Swami, Praveen (24 June 2020). "As PLA Seeks to Cut Off Indian Patrol Routes on LAC, 'Bottleneck' Emerges as Roadblock in Disengagement". News18. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Bagchi, Indrani (26 June 2020). "India China stand-off: Not just a border conflict, there's much more to it". The Times of India. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Unfazed by China Threat, 10k Men Working on BRO Projects in Ladakh". The Quint. 21 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Special Train Carrying Construction Workers For BRO Work in Ladakh Reaches J&K's Udhampur". CNN-News18. PTI. 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Gurung, Shaurya Karanbir (13 June 2020). "3,500 Jharkhand workers to be hired for Ladakh road projects". The Economic Times. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Chaturvedi, Amit, ed. (26 June 2020). "Govt gives salary hike of upto 170% to people working on building roads in border areas: Report". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Bagchi, Indrani (15 June 2020). "Jaishankar to meet China FM in virtual RIC meet on June 22". The Times of India. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Gill, Prabhjote (29 May 2020). "India says there are five treaties to push the Chinese army behind the Line of Actual Control – while experts tell Modi to remain cautious". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Agreement between the Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the People's Republic of China on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question". Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Sino-India relations including Doklam, Situation and Cooperation in International Organizations (2017-18) (PDF) (Report). Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

- Sudarshan, V. (1 June 2020). "A phantom called the Line of Actual Control". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Mitra, Devirupa (6 June 2020). "Ahead of Border Talks With China, India Still Unclear of Reason Behind Troops Stand-Off". The Wire. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

On Saturday, Indian and Chinese military officials of Lieutenant General-rank are likely to meet at a border personnel meeting (BPM)... The various BPM meetings – led first by colonels, then brigadiers and then finally over three rounds by major general-rank officers – have until now yielded no results.

- Gupta, Shishir (5 June 2020). "Ahead of today's meet over Ladakh standoff, India signals a realistic approach". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Talks over between military commanders of India, China". The Economic Times. ANI. 6 June 2020. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Som, Vishnu (6 June 2020). "India, China Top Military-Level Talks Amid Stand-Off in Ladakh". NDTV. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Ray, Meenakshi, ed. (6 June 2020). "Chinese mouthpiece shrills the pitch on Ladakh standoff, warns India over US ties". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Srinivasan, Chandrashekar, ed. (17 June 2020). "Anti-China Protests Across India, Delhi's Defence Colony Declares "War"". NDTV.com. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "UP: Anti-China protests across Gorakhpur-Basti zone, Chinese president's effigy burnt". India Today. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Laskar, Rezaul H; Singh, Rahul; Patranobis, Sutirtho (18 June 2020). "India warns China of serious impact on ties, Modi talks of 'befitting' reply". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Myers, Steven Lee; Abi-Habib, Maria; Gettleman, Jeffrey (17 June 2020). "In China-India Clash, Two Nationalist Leaders With Little Room to Give". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- BeijingJune 20, Press Trust of India; June 20, 2020UPDATED:; Ist, 2020 20:28. "Chinese social media deletes PM Modi, MEA's statements on India-China standoff". India Today. Retrieved 20 June 2020.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "India posts PM Modi's remarks on Ladakh face-off, China's WeChat app deletes it". Hindustan Times. 20 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Mankani, Prachi (20 June 2020). "Amid border row, Chinese social media deletes PM Modi's statement on the Galwan clash". Republic World. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "2020年6月24日外交部发言人赵立坚主持例行记者会 – 中华人民共和国外交部". fmprc.gov.cn. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Kumar, Ravi Prakash (19 June 2020). "India-China News: Boycotting China is like curing cancer, says Sonam Wangchuk on Galwan Valley clash". Livemint. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Ganai, Naseer (30 May 2020). "Magsaysay Awardee Sonam Wangchuk Calls For 'Boycott Made in China'". Outlook India. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "'Boycott Chinese products': Milind Soman quits TikTok after 3 Idiots' inspiration Sonam Wangchuk's call". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "China reacts cautiously to mounting boycott calls of its products in India, says it values ties". India Today. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Thomas, Tanya (19 June 2020). "MMRDA cancels ₹500 crore monorail tender which had only Chinese bidders". Livemint. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Sikarwar, Deepshikha (26 June 2020). "100% physical check of imports: Non-Chinese companies like Apple may be exempt". The Economic Times. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Raghavan, Prabha (27 June 2020). "Now, Indian exporters complain shipments stuck at China ports". The Indian Express. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Shrivastava, Rahul (16 June 2020). "Chinese firm bids lowest for Delhi-Meerut project, RSS affiliate asks Modi govt to scrap company's bid". India Today. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Haryana cancels tender after Chinese firms submitted bids". The Hindu. Special Correspondent. 21 June 2020. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 June 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Delete 52 apps, from phones, UP STF personnel told". The Indian Express. 20 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "After Galwan clash, states look to end contracts with Chinese firms". Hindustan Times. 21 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Easier said". The Indian Express. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Kaul, Vivek (7 June 2020). "It's impossible to boycott Chinese products and brands". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Shenoy, Sonia (15 June 2020). "Banning Chinese imports or raising tariffs on them will hurt industry, consumer, say Maruti, Bajaj Auto". cnbctv18.com. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Sen, Sesa (18 June 2020). "LAC standoff: Boycott of China products a tall order, trade unlikely to be hurt". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Pengonda, Pallavi (29 June 2020). "Key sectors caught in crossfire as tensions rise on China border". Livemint. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Dey, Sushmi (23 June 2020). "China Import to India: Government to curb pharma imports from China". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Government may extend anti-dumping duty on Chinese chemical". The Economic Times. Press Trust of India. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "India must not let border scuffle fray economic relations with China - Global Times". Global Times. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- howindialives.com (26 June 2020). "Despite hype about billion-dollar deals, China is a minor investor in India". Livemint. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Sarin, Ritu (21 June 2020). "Army's protective gear has Made in China link, Niti member says relook". The Indian Express. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "No Quality Issues in Army Bulletproof Jacket Material Imported From China, Says Niti Aayog Member". The Wire. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Bali, Pawan (20 June 2020). "Indian Army to get 100 per cent Made in India 'Sarvatra Kavach' body armour". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Sharma, Samrat (22 June 2020). "Maharashtra puts Chinese deals on hold, Yogi Adityanath's UP takes tough stand on imports from China". The Financial Express. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Bhuyan, Rituparana (23 June 2020). "Chinese imports curbs: DPIIT shares second list of 1172 items; India Inc worried about supply chain". CNBC TV18. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Mankotia, Anandita Singh (20 June 2020). "Industry told to submit list of Chinese imports". The Economic Times. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Pattanayak, Banikinkar (24 June 2020). "Point of no return? China border row adds to India's unease over RCEP". The Financial Express. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Kotoky, Anurag (18 June 2020). "Border Conflict Does Little to Damp Chinese Phone Sales in India". BloombergQuint. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "As Boycott China Trends on Social Media, OnePlus 8 Pro Sells Out Within Minutes". News18. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Lohchab, Himanshi; Guha, Romit (25 June 2020). "Boycott China: Xiaomi more Indian than local handset companies, says India MD". The Economic Times. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Banerjee, Prasid (27 June 2020). "CAIT condemns Jain for saying anti-China sentiments are on social media only". Livemint. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "CAIT condemns Xiaomi India head comment". The Financial Express. PTI. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Chandramouli, Rajesh (28 June 2020). "TTK Prestige to stop imports from China". The Times of India. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "'Google Uighur Muslims': Why Omar doesn't want Kashmiris to see China as saviour". The Week. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Shah, Khalid. "Kashmir's odd reaction to the Ladakh standoff". ORF. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Ganai, Naseer (25 June 2020). "'Always With Indian Army, But Restore Communication Services': Ladakh Councillors To Govt". Outlook India. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Westcott, Ben; Sud, Vedika (4 June 2020). "Indian defense minister admits large Chinese troop movements on border". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Roy, Divyanshu Dutta, ed. (2 June 2020). "US Foreign Affairs Panel Chief Slams 'Chinese Aggression' Against India". NDTV. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Sharma, Akhilesh (2 June 2020). "PM Modi, Trump Discuss India-China Border Tension, George Floyd Protests". NDTV. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Galwan valley clash: Mike Pompeo extends deepest condolences to Indians for loss of soldiers' lives in clashes with Chinese". The Times of India. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "India-China face-off: US, France, Japan and others mourn soldiers' death". The Economic Times. 20 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Ladakh face-off | U.S. talking to India and China, will try and help them out, says Donald Trump". The Hindu. PTI. 21 June 2020. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 June 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Bagchi, Indrani (26 June 2020). "Mike Pompeo: Moving Europe troops to counter China threat to India: US". The Times of India. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Jha, Lalit K (27 June 2020). "China's actions in Ladakh part of large-scale military provocations against neighbours: US lawmaker". Outlook India. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Confident India and China Will Find Way Out, Says 'Worried' Russia". The Wire. 1 June 2020. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Sino-Indian military face-off in Ladakh worries Russia". Deccan Chronicle. 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Basu, Nayanima (5 June 2020). "India discussed China border tensions also with Russia, the same day Modi and Trump spoke". ThePrint. Retrieved 6 June 2020.