TikTok

TikTok (Chinese: 抖音; pinyin: Dǒuyīn) is a Chinese video-sharing social networking service owned by ByteDance, a Beijing-based internet technology company founded in 2012 by Zhang Yiming. It is used to create short dance, lip-sync, comedy and talent videos.[5] ByteDance first launched Douyin for the China market in September 2016. Later, TikTok was launched in 2017 for iOS and Android in most markets outside of China; however, it only became available in the United States after merging with Musical.ly on 2 August 2018. TikTok and Douyin are similar to each other, but run on separate servers and have different content to comply with Chinese censorship restrictions. The application allows users to create short music and lip-sync videos of 3 to 15 seconds[6][7] and short looping videos of 3 to 60 seconds. They also have global offices including Los Angeles, New York, London, Paris, Berlin, Dubai, Mumbai, Singapore, Jakarta, Seoul, and Tokyo.[8] The app is popular in East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the United States, Turkey, Russia, and other parts of the world.[9][10][11] TikTok and Douyin's servers are each based in the market where the respective app is available.[12]

| |

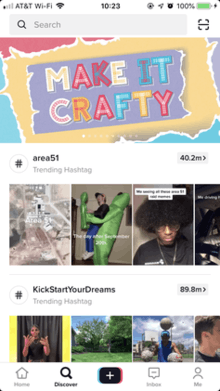

Screenshot  A screenshot of the iOS version of the TikTok app, as seen in the United States. | |

| Developer(s) | ByteDance |

|---|---|

| Initial release | September 2016. Released worldwide after merging with Musical.ly on 2 August 2018. |

| Stable release | 15.5.0

/ 31 March 2020 |

| Operating system | iOS, Android |

| Size | 308.3 MB (iOS)[1]

55.21 MB (Android)[2] |

| Available in | 40 languages[3] |

List of languages Arabic, Bengali, Burmese, Cambodian, Cebuano, Czech, Dutch, English, Filipino, French, German, Greek, Gujarati, Hindi, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Javanese, Kannada, Korean, Malay, Malayalam, Marathi, Oriya, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Romanian, Russian, Simplified Chinese, Spanish, Swedish, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Traditional Chinese, Turkish, Ukrainian, and Vietnamese | |

| Type | Video sharing |

| License | Proprietary software with Terms of Use |

| Alexa rank | |

| Website | tiktok.com douyin.com |

After merging with Musical.ly in August, downloads rose and TikTok became the most downloaded app in the US in October 2018, the first Chinese app to achieve this.[13][14] As of 2018, it was available in over 150 markets and in 75 languages. In February 2019, TikTok, together with Douyin, hit one billion downloads globally, excluding Android installs in China.[15] In 2019, media outlets cited TikTok as the 7th-most-downloaded mobile app of the decade, from 2010 to 2019.[16] It was also the most-downloaded app on the App Store in 2018 and 2019.

Since June 2020, Kevin Mayer is CEO of TikTok and COO of parent company ByteDance.[17] Previously he was chairman of the Walt Disney Direct-to-Consumer & International.[18]

History

Evolution

Douyin was launched by ByteDance in China in September 2016, originally under the name A.me, before rebranding to Douyin in December 2016.[19][20] ByteDance planned on Douyin expanding overseas. The founder of ByteDance, Zhang Yiming, stated that "China is home to only one-fifth of Internet users globally. If we don’t expand on a global scale, we are bound to lose to peers eyeing the four-fifths. So, going global is a must."[21] Douyin was developed in 200 days and within a year had 100 million users, with more than one billion videos viewed every day.[22][23] TikTok was launched in the international market in September 2017.[24] On 23 January 2018, the TikTok app ranked No. 1 among free app downloads on app stores in Thailand and other countries.[25]

TikTok has been downloaded more than 80 million times in the United States, and has reached 2 billion downloads worldwide[26], according to data from mobile research firm Sensor Tower that excludes Android users in China.[27] Many celebrities including Jimmy Fallon and Tony Hawk began using the application in 2018.[28][29] Other celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, Jessica Alba, Will Smith, and Justin Bieber joined TikTok as well and many other celebrities have followed.[30]

On 3 September 2019, TikTok and the US National Football League (NFL) announced a multi-year partnership.[31] The agreement occurred just two days shy of the NFL's 100th season kick off at the Soldier stadium, where TikTok hosted activities for fans in honor of the deal. The partnership entails the launch of an official NFL TikTok account which will bring about new marketing opportunities such as sponsored videos and hashtag challenges.

Musical.ly merger

On 9 November 2017, TikTok's parent company, ByteDance, spent up to $1 billion to purchase musical.ly, a startup based in Shanghai with an office in Santa Monica, California.[32][33] Musical.ly was a social media video platform that allowed users to create short lip-sync and comedy videos, initially released in August 2014. It was well known, especially to the younger audience. Looking forward to leveraging the US digital platform's young user base, TikTok merged with musical.ly on August 2, 2018 to create a larger video community, with existing accounts and data consolidated into one app, keeping the title TikTok. This ended musical.ly and made TikTok a world-wide app, excluding China, since China has Douyin.[33][34][35]

Expansion in other markets

As of 2018, TikTok has been made available in over 150 markets, and in 75 languages.[36][37] TikTok was downloaded more than 104 million times on Apple's App store during the full first half of 2018, according to data provided to CNBC by Sensor Tower. It surpassed Facebook, YouTube and Instagram to become the world's most downloaded iOS app.[38][39]

Douyin

As a separate app from TikTok, Douyin is available from the developer's website. The app can only be downloaded in China and has a slightly older audience than TikTok, as their user base ranges from children to middle-aged adults. The app uses two different types of verification, an influencer personal verification similar to that of TikTok and a business verification requiring a licence and yearly fee. Business verified users can promote to a specific audience, which allows them to choose where they want their video to be seen, such as a specific physical location. Douyin also has its own store, in which users can tag and advertise their products, and users can request to work with an influencer for brand deals.[40] Part of the app's popularity has been attributed to its marketing campaigns that launched several activities with Chinese celebrities to engage their fans' interest.[41]

Features and trends

The TikTok mobile app allows users to create a short video of themselves which often feature music in the background, can be sped up, slowed down or edited with a filter.[42] They can also add their own sound on top of the background music. To create a music video with the app, users can choose background music from a wide variety of music genres, edit with a filter and record a 15-second video with speed adjustments before uploading it to share with others on TikTok or other social platforms.[43] They can also film short lip-sync videos to popular songs.

The app's "react" feature allows users to film their reaction to a specific video, over which it is placed in a small window that is movable around the screen.[44] Its "duet" feature allows users to film a video aside another video.[45] The “duet” feature was another trademark of Musical.ly.

Videos that users do not want to post yet can be stored in their "drafts". The user is allowed to see their "drafts" and post when they find it fitting.[46]

The app allows users to set their accounts as "private." When first downloading the app, the user's account is public by default. The user can change to private in their settings. Private content remains visible to TikTok, but is blocked from TikTok users who the account holder has not authorized to view their content.[47] Users can choose whether any other user, or only their "friends", may interact with them through the app via comments, messages, or "react" or "duet" videos.[44] Users also can set specific videos to either “public”, “friends only”, or “private” regardless if the account is private or not.[47]

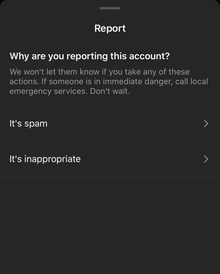

Users are also allowed to report accounts depending on the account's content either being spam or inappropriate. In TikTok's support center under "For Parents", they reassure the parents that inappropriate content for their children can be blocked and reported.[48]

The “For You” page on TikTok is a feed of videos that are recommended to users based on their activity on the app. Content is generated by TikTok's artificial intelligence (AI) depending on what kind of content a user liked, interacted with, or searched. Users can also choose to add to favorites or select "not interested" on videos in their for you page. TikTok combines the user's enjoyed content to provide videos that they would also enjoy. Users and their content can only be featured on the “for you” page if they are 16 or over as per TikTok policy. Users under 16 will not show up under the “for you” page, the sounds page, or under any hashtags.[49]

When users follow other users, a "following" page is located on the left of the "for you" page. This is a page to only see the videos from the user's following.

Users can also add videos, hashtags, filters, and sounds to their “saved” section. When creating a video, they can refer to their saved section, or create a video straight from it. This section is visible only to the user on their profile allowing them to refer back to any video, hashtag, filter, or sound they've previously saved.

Users can also send their friends videos, emojis, and messages with direct messaging.

TikTok has also included a feature to create a video based on the user's comments.

Influencers often use the "live" feature. This feature is only available for those who have at least 1,000 followers and are over 16 years old. If over 18, the user's followers can send virtual "gifts" that can be later exchanged for money.[50][51]

One of the newest features as of 2020 is the "Virtual Items" of "Small Gestures" feature. This is based on China's big practice of social gifting. Since this feature was added, many beauty companies and brands created a TikTok account to participate and advertise this feature. With quarantine in the United States, social gifting has grew in popularity. According to a TikTok representative, the campaign was launched as a result of the lockdown, “to build a sense of support and encouragement with the TikTok community during these tough times.”[52]

TikTok announced a "family safety mode" in February 2020 for parents to be able to control their children's digital well being. There is a screen time management option, restricted mode, and can put a limit on direct messages.[53][54]

Artificial intelligence

TikTok employs artificial intelligence to analyze users' interests and preferences through their interactions with the content, and display a personalized content feed for each user.[55][56] TikTok has an algorithm in which they process the user's preferences based on the videos they "like", comment on, and also how long they watch the video. Compared to other consumer algorithms such as YouTube and Netflix with a list of recommended videos, TikTok interprets the user's individual preferences and provides content that they would enjoy.[57]

Viral trends

There are a variety of trends within TikTok, including memes, lip-synced songs, and comedy videos. Duets, a feature that allows users to add their own video to an existing video with the original content's audio, have sparked most of these trends.

Trends are shown on TikTok's explore page or the page with the search logo. The page enlists the trending hashtags and challenges among the app. Some include #posechallenge, #filterswitch, #dontjudgemechallenge, #homedecor, #hitormiss, #bottlecapchallenge and more. In June 2019, the company introduced the hash tag #EduTok which received 37 billion views. Following this development the company initiated partnerships with edtech start ups to create educational content on the platform.[58]

The app has spawned numerous viral trends, internet celebrities, and music trends around the world.[59] Many stars got their start on musical.ly, which turned into the global platform known as TikTok on August 2, 2018. These users include Loren Gray, Baby Ariel, Kristen Hancher, Zach King, Lisa and Lena, Jacob Sartorius, and many others. Loren Gray remained the most-followed individual on TikTok until Charli D’Amelio surpassed her on March 25, 2020. Loren was the first TikTok account to reach 40 million followers on the platform, and Charli was the first with 60 million.

Charli D'Amelio started her career on TikTok and currently is the most-followed individual on the platform, with more than 62 million followers.[60] Charli D’Amelio rose to fame after duetting another TikTok user that went viral. She is also well known for performing a dance called "The Renegade," to the song "Lottery" by K CAMP. D’Amelio was part of the Hype House, a mansion in Los Angeles with a group of TikTok stars. The Hype House was founded by Daisy Keech, Chase Hudson, Alex Warren, Kouvr Annon, and Thomas Petrou in 2019.[61] Charli D’Amelio and her sister Dixie D'Amelio reportedly left the Hype House, along with Daisy Keech and Addison Rae. Current members of the Hype House are Chase Hudson, Connor Yates, Alex Warren, Avani Gregg, Wyatt Xavier, Ryland Storms, Nick Austin, Ondreaz Lopez, Tony Lopez, Kouvr Annon, Thomas Petrou, Calvin Goldby, James Wright, Jack Wright and Patrick Huston.[62]

Aside from "The Renegade" that had over 29.7 million videos, a notable TikTok trend is the "hit or miss", from a snippet of iLOVEFRiDAY's "Mia Khalifa" (2018), which has been used in over four million TikTok videos. This song helped introduce the app to a larger Western audience.[63][64] Other songs that have gained popularity because of their success on the app include "Roxanne" by Arizona Zervas, "Lalala" by bbno$, "Stupid" by Ashnikko, "Yellow Hearts" by Ant Saunders, "Say So" by Doja Cat, "Truth Hurts" by Lizzo, “Savage” by Megan Thee Stallion, and “Play Date” by Melanie Martinez. TikTok played a major part in making "Old Town Road" by Lil Nas X become one of the biggest songs of 2019, and the longest running #1 song on the Billboard Hot 100.[65][66][67][68][69]

TikTok has allowed bands to get notoriety in places all around the globe. The band Fitz and The Tantrums has developed a large following in South Korea despite never having toured in Asia.[70] "Any Song" by R&B and rap artist Zico became number 1 on the Korean music charts due to the popularity of the #anysongchallenge, where users dance the choreography of "Any Song". The song was on the Billboard Hot 100 chart for 17 weeks, breaking the record for the longest time a song was number 1 on the charts.[71] After his song "Old Town Road" went viral on the app, Lil Nas X received a record deal and the song rose to the top of the Billboard charts. The platform has received some criticism for its lack of royalties towards artists whose music is used on their platform.[64] There is controversy over whether or not this type of promotion is beneficial in the long run for artists since it seems to play as a "one-hit wonder".

In June 2020, TikTok users and K-pop fans "claimed to have registered potentially hundreds of thousands of tickets" for President Trump's campaign rally in Tulsa through communication on TikTok[72], contributing to "rows of empty seats"[73] at the event.

TikTok has banned holocaust denial, but other conspiracy theories have become popular on the platform, such as Pizzagate and QAnon (two conspiracy theories popular among the US alt-right) whose hashtags reached almost 80 million views and 50 million views respectively by June 2020.[74] The platform has also been used to spread misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic, such as clips from the Plandemic video.[74] TikTok removed some of these videos, and has generally added links to accurate COVID-19 information on videos with tags related to the pandemic.[75]

User characteristics and behavior

Users

In the three years after it launched in September 2016, TikTok acquired 800 million active users.[76] Its users include the likes of Zach King, Loren Gray, Baby Ariel, Lisa and Lena, Will Smith, Dwayne Johnson, Brent Rivera, Addison Rae, Jason Derulo, Jennifer Lopez, Camila Cabello, Selena Gomez, and Charli D'Amelio, the most-followed individual on the platform.

Demographics

In the United States, 52% of TikTok users are iPhone users. While TikTok has a neutral gender-bias format, 44% of TikTok users are female while 56% are male.[76] TikTok's geographical use has shown that 43% of new users are from India.[77] TikTok has proven to attract the younger generation, as 41% of its users are between the ages of 16 and 24. Among these TikTok users, 90% say they use the app on a daily basis.[78] As of May 2020, there are 30 million monthly active users in the United States alone.[79]

User engagement

As of July 2018, TikTok users spend an average of 52 minutes a day on the app, and 9 out of 10 users claim to use TikTok on a daily basis.[76]

Reception

TikTok became the world's most downloaded app on Apple's App Store in the first half of 2018 with an estimated 104 million downloads in that time.[38] Studies have shown that in just one year, short videos in China have gone up by 94.8 million.[80]

Cyberbullying

Similar to other platforms,[81] journalists in several countries have raised privacy concerns about the app, because it is popular with children and has the potential to be used by sexual predators.[81][82][83][84]

Several users have reported endemic cyberbullying on TikTok,[85][86] including racism.[87] In December 2019, following a report by German digital rights group Netzpolitik.org, TikTok admitted that it had suppressed videos by disabled users as well as LGBTQ+ users in a purported effort to limit cyberbullying.[88][89] TikTok moderators were also told to suppress users with "abnormal body shape,” "ugly facial looks,” "too many wrinkles,” or in "slums, rural fields” and "dilapidated housing” to prevent bullying.[90]

Addiction concerns

In addition, some users may find it hard to stop using TikTok.[91] In April 2018, an addiction-reduction feature was added to Douyin.[91] This encouraged users to take a break every 90 minutes.[91] Later in 2018, the feature was rolled out to the TikTok app. TikTok uses some of the top influencers such as Gabe Erwin, Alan Chikin Chow, James Henry, and Cosette Rinab to encourage viewers to stop using the app and take a break.[92]

Many were also concerned with users' attention spans with these videos. Users watch short 15-second clips repeatedly and studies say that this could report to a decrease in attention span. This is a concern as many of TikTok's audience is younger children, where their brain is still developing.[93]

User privacy concerns

Privacy concerns have also been brought up regarding the app.[94][95] In its privacy policy, TikTok lists that it collects usage information, IP addresses, a user's mobile carrier, unique device identifiers, keystroke patterns, and location data, among other data.[96][97] Web developers Talal Haj Bakry and Tommy Mysk claimed that allowing videos and other content being shared by the app's users through HTTP puts the users' data privacy at risk.[98]

In January 2020, Check Point Research discovered a security flaw in TikTok which could have allowed hackers access to user accounts using SMS.[99] In February, Reddit CEO Steve Huffman criticised the app, calling it "spyware," and stating "I look at that app as so fundamentally parasitic, that it's always listening, the fingerprinting technology they use is truly terrifying, and I could not bring myself to install an app like that on my phone."[100][101] Responding to Huffman's comments, TikTok stated "These are baseless accusations made without a shred of evidence."[96]

In May 2020, the Dutch Data Protection Authority announced an investigation into TikTok in relation to privacy protections for children.[102][103] In June 2020, the European Data Protection Board announced that it would assemble a task force to examine TikTok's user privacy and security practices.[104]

National security concerns

In January 2019, an investigation by the American think tank Peterson Institute for International Economics described TikTok as a "Huawei-sized problem" that posed a national security threat to the West,[105][106] noting the app's popularity with Western users. They included armed forces personnel and its alleged ability to convey location, image and biometric data to its Chinese parent company, which is legally unable to refuse to share data with the Chinese government under the China Internet Security Law.[106] Observers have also noted that ByteDance's founder and CEO Zhang Yiming issued a letter in 2018 stating that his company would "further deepen cooperation" with Communist Party of China authorities to promote their policies.[107] TikTok's parent company ByteDance claims that TikTok is not available in China and its data is stored outside of China, but its privacy policy has reserved the right to share any information with Chinese authorities.[108] In response to national security, censorship, and anti-boycott compliance concerns, in October 2019, Senator Marco Rubio asked the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States to open an investigation into TikTok and its parent company ByteDance.[109][110] The same month, senators Tom Cotton and Chuck Schumer sent a joint letter to the Director of National Intelligence requesting a security review of TikTok and its parent company.[111][112]

In November 2019, it was reported that the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States opened an investigation into ByteDance's acquisition of Musical.ly.[113] The same month, following a request by Senator Chuck Schumer, U.S. Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy agreed to assess the risks of using TikTok as a recruitment tool.[114][115] Senator Josh Hawley introduced the National Security and Personal Data Protection Act to prohibit TikTok's parent company and others from transferring personal data of Americans to China.[116] Senator Josh Hawley also introduced a bill to ban downloading and using TikTok on government devices because of national security concerns. In December 2019, the United States Navy as well as the U.S. Army banned TikTok from all government-issued devices.[117][118][119] The Transportation Security Administration also prohibited its personnel from posting on the platform for outreach purposes.[120][121] Following its prohibition by the U.S. military, the Australian Defence Force also banned TikTok on its devices.[122] Legislation was subsequently introduced in the U.S. Senate that would prohibit all federal employees from using or downloading TikTok.[123]

Censorship

On 3 July 2018, TikTok was banned in Indonesia after the Indonesian government accused it of promulgating "pornography, inappropriate content and blasphemy."[124][125][126][107][127] Shortly afterwards, TikTok pledged to task 20 staff with censoring TikTok content in Indonesia,[125] and the ban was lifted 8 days later.[124]

In November 2018, the Bangladeshi government blocked the TikTok app's internet access, even though TikTok had no connection to the reason for ban, which was pornography and gambling[128]

Also in 2018, Douyin was reprimanded by Chinese media watchdogs for showing "unacceptable" content, such as videos depicting adolescent pregnancies.[127]

In January 2019, the Chinese government said that it would start to hold app developers like ByteDance responsible for user content shared via apps such as Douyin,[129] and listed 100 types of content that the Chinese government would censor.[130] It was reported that certain content unfavorable to the Communist Party of China has already been limited for users outside of China such as content related to the 2019 Hong Kong protests.[131][132] TikTok has blocked videos about human rights in China, particularly those that reference Xinjiang re-education camps and abuses of ethnic and religious minorities, and disabled the accounts of users who post them.[133][134][135] TikTok's policies also ban content related to a specific list of foreign leaders such as Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Barack Obama, and Mahatma Gandhi because it can stir controversy and attacks on political views.[136] Its policies also ban content critical of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and content considered pro-Kurdish.[137] TikTok was reported to have censored users supportive of the Citizenship Amendment Act protests and those who promote Hindu-Muslim unity.[138]

In February 2019, several Indian politicians called for TikTok to be banned or more tightly regulated, after concerns emerged about sexually explicit content, cyberbullying, and deepfakes. They called it a "cultural degeneration".[90]

In countries where LGBT discrimination is the socio-political norm, TikTok moderators have blocked content that could be perceived as being positive towards LGBT people or LGBT rights, including same-sex couples holding hands, including in countries where homosexuality has never been illegal.[137][139] TikTok worked to create an environment in which their audience is comfortable and enjoy what they are watching. Former U.S. employees of TikTok reported to The Washington Post that final decisions to remove content were made by parent company employees in Beijing.[140]

In response to censorship concerns, TikTok's parent company hired K&L Gates, including former Congressmen Bart Gordon and Jeff Denham, to advise it on its content moderation policies.[141][142] TikTok also hired lobbying firm Monument Advocacy.[143]

In June 2020, The Times of India reported that TikTok was "shadow-banning" videos related to the Sino-Indian border dispute and the 2020 China–India skirmishes.[144]

Propaganda

In 2019, TikTok removed about two dozen accounts that were responsible of posting ISIS propaganda on the app.[145][146]

On 27 November 2019, TikTok temporarily suspended the account of 17-year-old Afghan-American user Feroza Aziz after she posted a video, disguised as a makeup tutorial, drawing attention to the internment camps of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang, China.[147] TikTok later apologized and claimed that her account was suspended as a result of human error, and her account has since been reinstated.[148]

In January 2020, Media Matters for America claimed that TikTok hosted misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic despite a recent policy against misinformation.[149] In April 2020, the government of India asked TikTok to remove users posting misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[150] Some of the misinformation that was given were that the coronavirus is not as bad as claimed. There were also multiple conspiracy theories that the government is involved with the spread of the pandemic.[151] As a response to this, TikTok launched a feature to report content for misinformation.[152]

In March 2020, internal documents leaked to The Intercept revealed that moderators had been instructed to suppress posts created by users deemed "too ugly, poor, or disabled" for the platform, and to censor political speech in livestreams, punishing those who harmed "national honor" or broadcast streams about "state organs such as police" with bans from the platform.[89][153] In June 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported that some previously non-political TikTok users were airing pro-Beijing views for the explicit purpose of boosting subscribers and avoiding "shadow" bans.[154]

Legal issues

Indonesian temporary block

Indonesia temporarily blocked the TikTok app on 3 July 2018 amid public concern about illegal content such as pornography and blasphemy that is not good for the youth. The app was unblocked one week later after TikTok negotiated, making various changes, including removing negative content, opening a government liaison office, and implementing age restrictions as well as security mechanisms.[155][156][157]

Tencent lawsuits

Tencent's WeChat platform has been accused of blocking Douyin's videos.[158][159] In April 2018, Douyin sued Tencent and accused it of spreading false and damaging information on its WeChat platform, demanding CNY one million in compensation and an apology. In June 2018, Tencent filed a lawsuit against Toutiao and Douyin in a Beijing court, alleging they had repeatedly defamed Tencent with negative news and damaged its reputation, seeking a nominal sum of CNY 1 in compensation and a public apology.[160] In response, Toutiao filed a complaint the following day against Tencent for allegedly unfair competition and asking for CNY 90 million in economic losses.[161]

US COPPA fines

On 27 February 2019, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) fined ByteDance US $5.7 million for collecting information from minors under the age of 13 in violation of the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act.[162] ByteDance responded by adding a kids-only mode to TikTok which blocks the upload of videos, the building of user profiles, direct messaging, and commenting on other's videos, while still allowing the viewing and recording of content.[163] In May 2020, an advocacy group filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission claiming that TikTok had violated the terms of the February 2019 consent decree, which sparked subsequent Congressional calls for a renewed FTC investigation.[164][165][166][167]

Brief ban in India

On 3 April 2019, the Madras High Court while hearing a PIL had asked the Government of India to ban the app, citing that it "encourages pornography" and shows "inappropriate content". The court also noted that children and minors using the app were at risk of being targeted by sexual predators. The court further asked broadcast media not to telecast any of those videos from the app. The spokesperson for TikTok stated that they were abiding by local laws and were awaiting the copy of the court order before they take action.[168] On 17 April, both Google and Apple removed TikTok from Google Play and the App Store.[169] As the court refused to reconsider the ban, the company stated that they had removed over 6 million videos that violated their content policy and guidelines.[170]

On 25 April 2019, the ban was lifted after a court in Tamil Nadu reversed its order of prohibiting downloads of the app from the App Store and Google Play, following a plea from TikTok developer Bytedance Technology.[171][172] India's TikTok ban might have cost the app 15 million new users.[173] Yet as of 2020, the number of Indian users have increased and now Indian head of TikTok Nikhil Gandhi expects that TikTok will at least grow by 50% by the end of 2020.[174]

Data transfer class action lawsuit

In November 2019, a class action lawsuit was filed in California that alleged that TikTok transferred personally-identifiable information of U.S. persons to servers located in China owned by Tencent and Alibaba.[175][176][177] The lawsuit also accused ByteDance, TikTok's parent company, of taking user content without their permission. The plaintiff of the lawsuit, college student Misty Hong, downloaded the app but claimed she never created an account. She realized a few months later that TikTok has created an account for her using her information (such as biometric) and made a summary of her information. The lawsuit also alleged that information was sent to Chinese tech giant Baidu.[178]

References

- "TikTok – Real Short Videos". App Store. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "TikTok". Play Store. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- "TikTok - Make Your Day". iTunes. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "tiktok.com Competitive Analysis, Marketing Mix and Traffic - Alexa". alexa.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Schwedel, Heather (4 September 2018). "A Guide to TikTok for Anyone Who Isn't a Teen". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Top 10 TikTok (Musical.ly) App Tips and Tricks". Guiding Tech. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "TikTok – Apps on Google Play". play.google.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "About | TikTok - Real Short Videos". www.tiktok.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Mohsin, Maryam (17 April 2020). "10 TikTok Statistics That You Need to Know in 2020 [Infographic]". oberlo.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "50 TikTok Stats That Will Blow Your Mind [Updated 2020]". Influencer Marketing Hub. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- RouteBot (21 March 2020). "Top 10 Countries with the Largest Number of TikTok Users". routenote.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Forget The Trade War. TikTok Is China's Most Important Export Right Now". Buzz Feed News. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Tik Tok, a Global Music Video Platform and Social Network, Launches in Indonesia-PR Newswire APAC". en.prnasia.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "How Douyin became China's top short-video App in 500 days – WalktheChat". WalktheChat. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "TikTok Pte. Ltd". Sensortower. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Rayome, Alison DeNisco. "Facebook was the most-downloaded app of the decade". CNET. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Zeitchik, Steven (18 May 2020). "In surprise move, a top Disney executive will run TikTok". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Barnes, Brooks (18 May 2020). "Disney's Head of Streaming Is New TikTok C.E.O." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "The App That Launched a Thousand Memes | Sixth Tone". Sixth Tone. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Is Douyin the Right Social Video Platform for Luxury Brands? | Jing Daily". Jing Daily. 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- "(PDF) TIKTOK'S RISE TO GLOBAL MARKETS 1". Researchgate.net. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Graziani, Thomas (30 July 2018). "How Douyin became China's top short-video App in 500 days". WalktheChat. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "8 Lessons from the rise of Douyin (Tik Tok) · TechNode". TechNode. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Tik Tok, a Global Music Video Platform and Social Network, Launches in Indonesia". Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- "Tik Tok, Global Short Video Community launched in Thailand with the latest AI feature, GAGA Dance Machine The very first short video app with a new function based on AI technology". thailand.shafaqna.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/29/21241788/tiktok-app-download-numbers-update-2-billion-users

- Yurieff, Kaya (21 November 2018). "TikTok is the latest social network sensation". Cnn.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019.

- Alexander, Julia (15 November 2018). "TikTok surges past 6M downloads in the US as celebrities join the app". The Verge. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Spangler, Todd (20 November 2018). "TikTok App Nears 80 Million U.S. Downloads After Phasing Out Musical.ly, Lands Jimmy Fallon as Fan". Variety. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "A-Rod & J.Lo, Reese Witherspoon and the Rest of the A-List Celebs You Should Be Following on TikTok". PEOPLE.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "The NFL joins TikTok in multi-year partnership". TechCrunch. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Lin, Liza; Winkler, Rolfe (9 November 2017). "Social-Media App Musical.ly Is Acquired for as Much as $1 Billion". wsj.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- "Social video app Musical.ly acquired for up to $1 billion". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Musical.ly Is Going Away: Users to Be Shifted to Bytedance's TikTok Video App". msn.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Kundu, Kishalaya (2 August 2018). "Musical.ly App To Be Shut Down, Users Will Be Migrated to TikTok". Beebom. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "Chinese video sharing app boasts 500 mln monthly active users - Xinhua | English.news.cn". xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Why China's Viral Video App Douyin is No Good for Luxury | Jing Daily". Jing Daily. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Chen, Qian (18 September 2018). "The biggest trend in Chinese social media is dying, and another has already taken its place". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "TikTok surpassed Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat & YouTube in downloads last month". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "A Thorough Guide to Influencing on Douyin - For Individuals and Businesses (2020)". Nanjing Marketing Group. 29 March 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Douyin launches partnership with Modern Sky to monetize music". Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "How to Use TikTok: Tips for New Users". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Matsakis, Louise (6 March 2019). "How to Use TikTok: Tips for New Users". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "TikTok adds video reactions to its newly-merged app". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Tik Tok lets you duet with yourself, a pal, or a celebrity". The Nation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Liao, Christina. "How to make and find drafts on TikTok using your iPhone or Android". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "It's time to pay serious attention to TikTok". TechCrunch. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Support Center | TikTok". support.tiktok.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "TikTok Restricts Users Under 16 From Being Discovered". TikTok. 31 January 2019. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Delfino, Devon. "How to 'go live' on TikTok and livestream video to your followers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "How To Go Live & Stream on TikTok". Tech Junkie. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "TikTok's social gifting campaign attracts beauty brands". Glossy. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Introducing Family Safety Mode and Screentime Management in Feed". Newsroom | TikTok. 16 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "TikTok gives parent remote control of child's app". BBC News. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Tech in Asia – Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem". techinasia.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- BeautyTech.jp (15 November 2018). "How cutting-edge AI is making China's TikTok the talk of town". Medium. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "How is Artificial Intelligence (AI) Making TikTok Tick? | Analytics Steps". analyticssteps.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "TikTok ties up with edtech startups for content creation". ETtech.com. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "How Does Tik Tok Outperform Tencent's Super App WeChat and Become One of China's Most Popular Apps? (Part 1)". kr-asia.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Charli D'Amelio becomes first TikTok star to reach 50 million followers". Metro. 22 April 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- Perrett, Connor. "TikTok's Hype House is home to some of the app's biggest stars, including Charli D'Amelio. Who are the other 20 members?". Insider. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "TikTok Star Charli D'Amelio Officially Leaves the Hype House". PEOPLE.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "TikTok's Renegade dance : An internet success across the United States". Blasting News. 12 March 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "How TikTok Gets Rich While Paying Artists Pennies". Pitchfork. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Coscarelli, Joe (9 May 2019), "How Lil Nas X Took 'Old Town Road' From TikTok Meme to No. 1 | Diary of a Song", The New York Times, YouTube, archived from the original on 10 November 2019, retrieved 26 November 2019

- Koble, Nicole (28 October 2019). "TikTok is changing music as you know it". British GQ. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Leskin, Paige (22 August 2019). "The life and rise of Lil Nas X, the 'Old Town Road' singer who went viral on TikTok and just celebrated Amazon Prime Day with Jeff Bezos". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Spanos, Brittany (December 2019). "How Lil Nas X and 'Old Town Road' Defy Categorization". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Kennedy, Gerrick D. (20 November 2019). "Lil Nas X makes Grammy history as the first openly gay rapper nominated in top categories". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Shaw, Lucas. "TikTok Is the New Music Kingmaker, and Labels Want to Get Paid". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "'Any Song' is a viral hit thanks to TikTok challenge: Rapper Zico's catchy song and dance have become a craze all around the world". koreajoongangdaily.joins.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "TikTok Teens and K-Pop Stans Say They Sank Trump Rally". 21 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "The President's Shock at the Rows of Empty Seats in Tulsa". 21 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Dellinger, A. J. (22 June 2020). "Conspiracy theories are finding a hungry audience on TikTok". Mic. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Strapagiel, Lauren (27 May 2020). "COVID-19 Conspiracy Theorists Have Found A New Home On TikTok". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "10 TikTok Statistics That You Need to Know in 2019 [Infographic]". Oberlo. 22 October 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "13 TikTok Stats for Marketers: TikTok Demographics, Statistics, & Key Data". Mediakix. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Meola, Andrew. "Analyzing Tik Tok user growth and usage patterns in 2020". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "20 Important TikTok Stats Marketers Need to Know in 2020". Hootsuite Social Media Management. 7 May 2020. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Hou. L., M.C.A., October 2018, Graduate School, Bangkok University Study on the Perceived Popularity of Tik Tok (75pp.) Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Rose ChongpornKomolsevin, Ph.D.

- "Les dangers de Tik Tok pour vos enfants et comment s'en prémunir". CNET France. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- WSPA (20 September 2018). "Tik Tok app raises concerns for young users". WNCT. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Zhang, Karen. "Tik Tok, currently the world's most popular iPhone app, under fire over lack of privacy settings – Tech News – The Star Online". scmp.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Koebler, Jason; Cox, Joseph (6 December 2018). "TikTok, the App Super Popular With Kids, Has a Nudes Problem". Vice. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "TikTok Creators Say They Are Being Bullied And The Company Isn't Helping". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Clock is ticking: Experts urge caution as popularity of TikTok surges". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "What is TikTok and is it safe?". The Week UK. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Lao, David (3 December 2019). "TikTok admits to suppressing videos from some persons with disabilities, LGBTQ2 community". Global News. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Biddle, Sam; Ribeiro, Paulo Victor; Dias, Tatiana (16 March 2020). "Invisible Censorship – TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by "Ugly" People and the Poor to Attract New Users". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Biddle, Sam; Ribeiro, Paulo Victor; Dias, Tatiana (16 March 2020). "Invisible Censorship: TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by "Ugly" People and the Poor to Attract New Users". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Lip syncing, finger dancing – Hong Kong kids go crazy for Tik Tok". South China Morning Post. 19 May 2018. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Stokel-Walker, Chris. "TikTok influencers are telling people to stop using the app". Input. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Su, Xiaochen (8 May 2020). "The Trouble With TikTok's Global Rise". The News Lens International Edition. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Wong, Queenie (2 December 2019). "TikTok accused of secretly gathering user data and sending it to China". CNET. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Bergman, Ronen; Frenkel, Sheera; Zhong, Raymond (8 January 2020). "Major TikTok Security Flaws Found". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Mahadevan, Tara C. (27 February 2020). "TikTok Responds After Reddit CEO Calls It 'Fundamentally Parasitic'". Complex. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Privacy Policy (If you are a user having your usual residence in the US)". TikTok. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Army joins Navy in banning TikTok". SC Media. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "TikTok flaws could have allowed hackers access to user accounts through an SMS". Hindustan Times. 8 January 2020. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Hamilton, Isobel Asher (27 February 2020). "Reddit's CEO described TikTok as 'parasitic' and 'spyware'". Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Matney, Lucas (27 February 2020). "Reddit CEO: TikTok is 'fundamentally parasitic'". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Deutsch, Anthony (8 May 2020). "Dutch watchdog to investigate TikTok's use of children's data". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Bodoni, Stephanie (8 May 2020). "TikTok Faces Dutch Privacy Probe Over Children's Data". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Yun Chee, Foo (10 June 2020). "EU watchdog sets up TikTok task force, warns on Clearview AI software". Reuters. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "The Growing Popularity of Chinese Social Media Outside China Poses New Risks in the West". PIIE. 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Report warns of security concerns amid sudden..." Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Spence, Philip (16 January 2019). "ByteDance Can't Outrun Beijing's Shadow". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "The Kids Use TikTok Now Because Data-Mined Videos Are So Much Fun". Bloomberg News. 18 April 2019. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Romm, Tony; Harwell, Drew (9 October 2019). "Sen. Rubio: U.S. government should probe TikTok over Chinese censorship concerns". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Nicas, Jack; Isaac, Mike; Swanson, Ana (1 November 2019). "TikTok Said to Be Under National Security Review". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Thorbecke, Catherine (25 October 2019). "Lawmakers say Chinese-owned app TikTok could pose 'national security risks'". ABC News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Pham, Sherisse (25 October 2019). "TikTok could threaten national security, US lawmakers say". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- Roumeliotis, Greg (1 November 2019). "U.S. opens national security investigation into TikTok – sources". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Bartz, Diane (12 November 2019). "U.S. Army should assess security risks of using TikTok for recruitment: Sen. Schumer". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Frazin, Rachel (22 November 2019). "Army taking security assessment of TikTok after Schumer warning". The Hill. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Harding McGill, Margaret (18 November 2019). "Hawley bill targets Apple and TikTok ties to China". Axios. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Bell, M.B.; Wang, Echo (20 December 2019). "U.S. Navy bans TikTok from government-issued mobile devices". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Calma, Justine (31 December 2019). "US Army bans soldiers from using TikTok". The Verge. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Harwell, Drew; Romm, Tony (31 December 2019). "U.S. Army bans TikTok on military devices, signaling growing concern about app's Chinese roots". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Balsamo, Michael (23 February 2020). "TSA halts employees from using TikTok for social media posts". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "Unpacking TikTok, Mobile Apps and National Security Risks". Lawfare. 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Bogle, Ariel (16 January 2020). "Soldiers are getting famous on TikTok, but the US and Australian military aren't fans". ABC News. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Baksh, Mariam (13 March 2020). "Senators Propose Barring TikTok from Government Devices". Nextgov.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- hermesauto (11 July 2018). "Indonesia overturns ban on Chinese video app Tik Tok". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Chinese video app Tik Tok to set up Indonesia censor team to..." Reuters. 5 July 2018. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019 – via uk.reuters.com.

- "Indonesia blocks 'pornographic' Tik Tok app". DW.COM. 7 May 2018. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "TikTok parent ByteDance sues Chinese news site that exposed fake news problem". TechCrunch.

- "Bangladesh 'anti-porn war' bans blogs and Google books". DW.COM. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Chinese government to start blaming social apps for what their users' post". Metro. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Davis, Rebecca; Davis, Rebecca (18 January 2019). "Farewell to Concubines: China Tightens Restrictions on Short-Form Videos". Variety. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Harwell, Drew; Romm, Tony (15 September 2019). "TikTok's Beijing roots fuel censorship suspicion as it builds a huge U.S. audience". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 September 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Hern, Alex (25 September 2019). "Revealed: how TikTok censors videos that do not please Beijing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Cockerell, Isobel (25 September 2019). "TikTok – Yes, TikTok – Is the Latest Window Into China's Police State". Wired. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Chan, Holmes; Grundy, Tom (27 November 2019). "'Suspension won't silence me': Teen speaks out after embedding message about Xinjiang Uyghurs in TikTok make-up vid". Hong Kong Free Press. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Handley, Erin (28 November 2019). "TikTok parent company complicit in censorship and Xinjiang police propaganda: report". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Hern, Alex (25 September 2019). "Revealed: how TikTok censors videos that do not please Beijing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Hern, Alex (26 September 2019). "TikTok's local moderation guidelines ban pro-LGBT content". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Christopher, Nilesh (31 January 2020). "Censorship claims emerge as TikTok gets political in India". BBC News. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Criddle, Cristina (12 February 2020). "Transgender users accuse TikTok of censorship". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Harwell, Drew; Romm, Tony (5 November 2019). "Inside TikTok: A culture clash where U.S. views about censorship often were overridden by the Chinese bosses". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Li, Jane (16 October 2019). "TikTok wants to prove it's not a new front in China's information war". Quartz. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Lee, Cyrus (16 October 2019). "TikTok hires legal experts for content moderation amid censorship concerns". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Brody, Ben; Wilson, Megan (12 November 2019). "TikTok Revamps Lobbying as Washington Targets Chinese Ownership". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Banerjee, Chandrima (6 June 2020). "Does TikTok censor content that's critical of China?". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Feuer, William (22 October 2019). "TikTok removes two dozen accounts used for ISIS propaganda". CNBC. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Wells, Georgia (23 October 2019). "Islamic State's TikTok Posts Include Beheading Videos". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Lee, David; Tannahill, Jordan (28 November 2019). "TikTok apologises and reinstates banned teen". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "TikTok Denies Censoring A Teen Who Criticized China's Concentration Camps – They Said They Banned Her After A Joke About Osama Bin Laden Thirst". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Kaplan, Alex (28 January 2020). "TikTok is hosting videos spreading misinformation about the coronavirus, despite the platform's new anti-misinformation policy". Media Matters for America. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Kalra, Aditya (7 April 2020). "India asks TikTok, Facebook to remove users spreading coronavirus misinformation". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Dickson, E. J.; Dickson, E. J. (13 May 2020). "On TikTok, COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories Flourish Amid Viral Dances". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Our efforts towards fighting misinformation in times of COVID-19". Newsroom | TikTok. 16 August 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Hern, Alex (17 March 2020). "TikTok 'tried to filter out videos from ugly, poor or disabled users'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Xiao, Eva (17 June 2020). "TikTok Users Gush About China, Hoping to Boost Views". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Indonesia overturns ban on Tik Tok after video streaming service agrees to increase security controls". South China Morning Post. Reuters. 11 July 2018. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Tech in Asia - Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem". www.techinasia.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Indonesia lifted the ban on Tik Tok after one-week Negotiation". Pandaily. 16 July 2018. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Tencent and Toutiao come out swinging at each other". Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Tencent sues Toutiao for alleged defamation, demands 1 yuan and apology". TODAYonline. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Jiang, Sijia (1 June 2018). "Tencent sues Toutiao for alleged defamation, demands 1 yuan and apology". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Tencent and Toutiao sue each other in escalating legal battle". Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Lieber, Chavie (28 February 2019). "TikTok is the latest social media platform accused of abusing children's privacy – now it's paying up". Vox. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "TikTok stops young users from uploading videos after FTC settlement". Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Bartz, Diane (14 May 2020). "Advocacy group says TikTok violated FTC consent decree and children's privacy rules". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Spangler, Todd; Spangler, Todd (14 May 2020). "TikTok Is Still Violating U.S. Child-Privacy Law, Groups Charge". Variety. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- May 14, Dan Clark |; PM, 2020 at 04:55. "Advocacy Groups Ask FTC to Reinvestigate TikTok Over Alleged COPPA Violations". Corporate Counsel. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Miller, Maggie (28 May 2020). "Democrats call on FTC to investigate allegations of TikTok child privacy violations". The Hill. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "'It Encourages Pornography': Madras High Court Asks Government to Ban Video App TikTok". News18. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Apple, Google Block TikTok in India After Court Order". NDTV. 17 April 2019. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- Chandrashekhar, Anandi (17 April 2019). "TikTok no longer available on Google and Apple stores". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "TikTok ban lifted in India but it has lost at least 2 million users". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "TikTok Ban in India Lifted by Madras High Court". beebom.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "India's TikTok Ban Might Have Cost the App 15 Million New Users". beebom.com. 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "TikTok expects to have 300m users in India by end of 2020 - Music Ally". Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "TikTok sent user data to China, US lawsuit claims". BBC News. 3 December 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Montgomery, Blake (2 December 2019). "California Class-Action Lawsuit Accuses TikTok of Illegally Harvesting Data and Sending It to China". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Chen, Angela (5 December 2019). "TikTok's second lawsuit in a week brings a US ban a shade closer". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Narendra, Meera (4 December 2019). "#Privacy: TikTok found secretly transferring user data to China".

External links

- Official website (in English)

- ByteDance official website (in English)

- Douyin (in Chinese)