Insurgency in Punjab

The insurgency in Punjab originated in the early 1980s, was a rebellion against the government of India by a militant Sikh nationalist group called the Khalistan movement.[14] In the 1980s the movement had developed into a secessionist movement under the leadership of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.[15] The Green revolution brought several socio-economic changes which along with factionalism of the politics in the Punjab state increased tension between a section of Sikhs in Punjab with the union Government of India.[14] Pakistani strategists then began supporting the militant dimension of the Khalistan movement.[14]

| Punjab insurgency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

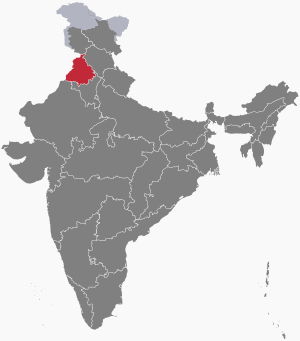

Affected areas coloured in Red | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by:

|

Khalistani militants | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale † Bhai Amrik Singh † Shabeg Singh † Manbir Singh Chaheru † Labh Singh † Kanwaljit Singh Sultanwind Paramjit Singh Panjwar Ranjit Singh Neeta Aroor Singh † Avtar Singh Brahma † Gurjant Singh Budhsinghwala † Navroop Singh † Navneet Singh Khadian † Pritam Singh Sekhon † Gurbachan Singh Manochahal † Balwinder Singh Talwinder Singh Parmar † Sukhdev Singh Babbar † Wadhawa Singh Babbar | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| 30,000 (est.) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,417 security forces killed[10] 249 security forces injured[11][12] | 8,600 Khalistani militants killed[13] | ||||||

| 12,000 civilian deaths[13] | |||||||

In 1972 Punjab state elections, Congress won and Akali Dal was defeated. In 1973 Akali Dal put forward the Anandpur Sahib Resolution to demand more autonomic powers to the state of Punjab.[16] The Congress government considered the resolution a secessionist document and rejected it.[17] Bhindranwale then joined the Akali Dal to launch the Dharam Yudh Morcha in 1982, to implement Anandpur Sahib resolution. Bhindranwale had risen to prominence in the Sikh political circle with his policy of getting the Anandpur Resolution passed, failing which he wanted to declare a separate country of Khalistan as a homeland for Sikhs.[18]

Bhindranwale symbolized the revivalist, extremist and terrorist movement in the 1980s in Punjab.[19] He is credited with the launching the Sikh militancy in Punjab,[15] with training and support from the spy agency ISI of Pakistan.[7] Under Bhindranwale, the number of people initiating into the Khalsa increased. He also increased the level of rhetoric on the perceived "assault" on Sikh values from the Hindu community.[15] Bhindranwale and his followers started carrying firearms at all times.[15] In 1983, to escape arrest, he along with his militant cadre occupied and fortified the Sikh shrine Akal Takht .[20] He made the Sikh religious building his headquarters and led the terrorist campaign in Punjab with the strong backing of Major General Shabeg Singh.[21]

On 1 June Operation Blue Star was launched to remove him and the armed militants from the Golden Temple complex. On 6 June Bhindranwale was killed by military in the operation.[22] The operation carried out in the Gurudwara caused outrage among the Sikhs and increased the support for Khalistan Movement.[14] Four months after the operation, on 31 October 1984, Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi was assassinated in vengeance by her two bodyguards, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh.[23] Public outcry over Gandhi's death led to the slaughter of Sikhs in the ensuing 1984 Sikh Massacre.[24] These events played a major role in the violence by Sikh militant groups supported by Pakistan and consumed Punjab until the early 1990s when the Khalistan movement eventually died out.[25]

The extremist violence had started with targeting of the Nirankaris and followed by attack on the government machinery and the Hindus. Ultimately the Sikh militants also targeted other Sikhs with opposing viewpoints. This led to further loss of public support and the militants were eventually brought under control of law enforcement agencies by 1993.[26]

Background

In the 1950s there was a demand for linguistic reorganisation of the state of Punjab, which the government finally agreed in 1966 after protests and recommendation of the States Reorganisation commission.[14] The state of Punjab was later split into the states of Himachal Pradesh, the new state Haryana and current day Punjab.[27]

While the Green Revolution in Punjab had several positive impacts, the introduction of the mechanised agricultural techniques led to uneven distribution of wealth. The industrial development was not done at the same pace of agricultural development, the Indian government had been reluctant to set up heavy industries in Punjab due to its status as a high-risk border state with Pakistan.[28] The rapid increase in the higher education opportunities without adequate rise in the jobs resulted in the increase in the unemployment of educated youth.[14] The resulting unemployed rural Sikh youth were drawn to the militant groups, and formed the backbone of the militancy.[29]

Anandpur Sahib Resolution and Khalistan

After being routed in 1972 Punjab election, the Akali Dal put forward the Anandpur Sahib Resolution in 1973 to demand more autonomy to Punjab.[16] The resolution included both religious and political issues. It asked for recognising Sikhism as a religion separate from Hinduism. It also demanded that power be generally devoluted from the Central to state governments.[14] The Anandpur Resolution was rejected by the government as a secessionist document. Bhindranwale then joined the Akali Dal to launch the Dharam Yudh Morcha in 1982, to implement Anandpur Sahib resolution. Thousands of people joined the movement, feeling that it represented a real solution to demands such as a larger share of water for irrigation and the return of Chandigarh to Punjab.[30]

Bhindranwale had risen to prominence in the Sikh political circle with his policy of getting the Anandpur Resolution passed, failing which he wanted to declare a separate country of Khalistan as a homeland for Sikhs.[18] Indira Gandhi, the leader of the Akali Dal's rival Congress, considered the Anandpur Sahib Resolution as a secessionist document.[17] The Government was of the view that passing of the resolution would have allowed India to be divided, making a Khalistan.[31]

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and the Akalis

Attempts were made by the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi to prop up Bhindranwale to undermine the Akali Dal, a Sikh religious political party.[32][21] On 13 April 1978, the day to celebrate the birth of Khalsa, a Sant Nirankari convention was organized in Amritsar, with permission from the Akali state government. The practices of "Sant Nirankaris" sect of Nirankaris was considered as heretics by the orthodox Sikhism expounded by Bhindranwale.[32] From Golden Temple premises,[33] A procession of about two hundred Sikhs led by Bhindranwale and Fauja Singh of the Akhand Kirtani Jatha left the Golden Temple, heading towards the Nirankari Convention. In the ensuing violence seventeen people were killed.[34] A criminal case was filed and accused were acquitted on self defence.[35] The Punjab government Chief Minister Prakash Singh Badal decided not to appeal the decision.[36]

Bhindranwale increased his rhetoric against the enemies of Sikhs. A letter of authority was issued by Akal Takht to ostracize the Sant Nirankaris. A sentiment was created to justify extra judicial killings of the perceived enemies of Sikhism.[37] The chief proponents of this attitude were the Babbar Khalsa founded by the widow, Bibi Amarjit Kaur of the Akhand Kirtani Jatha, whose husband Fauja Singh had been at the head of the march in Amritsar; the Damdami Taksal led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale who had also been in Amritsar on the day of the outrage; the Dal Khalsa, formed with the object of demanding a sovereign Sikh state; and the All India Sikh Students Federation, which was banned by the government.

In the subsequent years following this event, several murders took place in Punjab and the surrounding areas by Bhindranwale's group and the new Babbar Khalsa.[35] The Babbar Khalsa activists took up residence in the Golden Temple, where they would retreat to, after committing "acts of punishment" on people against the orthodox Sikh tenets. Police did not entered the temple complex to avoid hurting the sentiments of Sikhs.[35] On 24 April 1980, The Nirankari head, Gurbachan was murdered.[38] Bhindranwale took residence in Golden Temple to escape arrest when he was accused of the assassination of Nirankari Gurbachan Singh.[39] Three years later, a member of the Akhand Kirtani Jatha, Ranjit Singh, surrendered and admitted to the assassination.

Pakistan involvement

In 1964, Pakistani state owned radio station began airing separatist propaganda targeted for Sikhs in Punjab, which continued during the Indo-Pak war of 1965.[40] Pakistan had been helping the Sikh secessionist movement since the 1970s. The Pakistani prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had politically supported the idea of Khalistan wherever possible. Under Zia ul Haq, this support became even more prominent. The motive for supporting Khalistan was the revenge for India's role in splitting of Pakistan in 1971 and to discredit India's global status by splitting a Sikh state to vindicate Jinnah's Two-nation theory.[6] Zia had seen this as an opportunity to weaken and distract India in another war of insurgency following the Pakistani military doctrine to "Bleed India with a Thousand Cuts". Hamid Gul (who had led ISI) had stated about Punjab insurgency that "Keeping Punjab destabilized is equivalent to the Pakistan Army having an extra division at no cost to the taxpayers."[41]

Punjab Cell of ISI

Since the early 1980s, for the fulfillment of these motives, the spy agency Inter-Service-Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan became involved with the Khalistan movement.[6] ISI created a special Punjab cell in its headquarter to support the militant Sikh followers of Bhindranwale and supply them with arms and ammunitions. Terrorist training camps were set up in Pakistan at Lahore and Karachi to train the young khalistanis. ISI deployed its Field Intelligence Units (FIU) on the Indo-Pak Border. The Bhindranwale Tiger Force, the Khalistan Commando Force, the Khalistan Liberation Force and the Babbar Khalsa were the major insurgent groups that were provided support.[6]

A three phase plan was followed by the Punjab cell of ISI.[6]

- Phase 1 had the objective to initiate alienation of the Sikh people from rest of the people in India.

- Phase 2 worked to subvert government organisation and organize mass agitations opposing the government.

- Phase 3 marked the beginning of a reign of terror in Punjab where the civilians became victims of violence by the militants and counter-violence by the government.[6]

Sikh Religious bodies

The ISI had also included the Panthic Committee in India as an additional partner. The five membered Panthic Committee was elected from among the religious leaders of the Panth, and acted as the upholders of the Sikh religion. Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, which served as the custodians of all Sikh Shrines was also appealed by ISI. SGPC was established through the Gurdwara Act of 1925 and had substantial financial resources. Both these Sikh committee had major political influence over Punjab and New Delhi.[6]

Sikhs in Pakistan were a small minority and the Panthic Committee in Pakistan assisted the propaganda campaign of ISI in its propaganda and psychological warfare. The Sikh community in the country and abroad were its target. Panthic Committee instigated Sikhs by delivering religious speeches and revealing incidents of torture to the Sikhs. Sikhs were instigated to take up arms against the Indian Government "in the name of a hypothetical autonomous Sikh nation".[6]

ISI used Pakistani Sikhs as partners for its operation in the Indian Punjab. The terrorist training program was spread over and the Sikh gurdwaras on both sides of International border were used as place for residence and armoury for storing weapons and ammunitions.[6]

The direct impact of these activities was felt during the Operation Blue Star where the Sikh insurgents fighting against the army were found to be well trained in warfare and had enough supply of ammunitions.[6] After the Operation Blue Star several modern weapons found inside the temple complex with the Pakistan or Chinese markings on them.[42]

Training and infrastructure

Pakistan has been deeply involved in the training, guiding and arming Sikh militants.[6] Wadhawa Singh, Chief Babbar Khalsa International (BKI), Lakhbir Singh Rode, Chief, International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF), Paramjit Singh Panjwar, Chief, Khalstan Commando Force (KCF), Gajinder Singh, Chief, Dal Khalsa International (DKI) and Ranjit Singh Neeta, Chief, Khalistan Zindabad Force (KZF) permanently based in Pakistan, have been coordinating militant activities of their outfits in Punjab and elsewhere in India under the guidance of Pak ISI. Pak ISI agents regularly escort Sikh militants for trans-border movement and provide safe havens for their shelter and dumps for weapons and explosives.

Interrogation reports of Sikh militants arrested in India gave details of the training of Sikh youth in Pakistan including arms training in the use of rifle, sniper rifle, light machine gun, grenade, automatic weapons, chemical weapons, demolition of buildings and bridges, sabotage and causing explosions using gunpowder by the Pak-based Sikh militant leaders and Pakistani army officers. A dozen terrorist training camps had been set up in Pakistan along the International border. These camps housed 1500 to 2000 Sikh militants who were imparted guerilla warfare training.[40] These reports also suggest plans of Pak ISI through Pak based terrorists to cause explosions in big cities like Amritsar, Ludhiana, Chandigarh, Delhi and targeting of VVIPs.[43][44]

Militancy

A section of Sikhs turned to militancy in Punjab; some Sikh militant groups aimed to create an independent state called Khalistan through acts of violence directed at members of the Indian government, army or forces. Others demanded an autonomous state within India, based on the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. A large numbers of Sikhs condemned the actions of the militants.[45]

Anthropological studies have identified fun, excitement and expressions of masculinity, as explanations for the young men to join militants and other religious nationalist groups. Puri et al. state that undereducated and illiterate young men, and with few job prospects had joined pro-Khalistan militant groups with “fun” as one of the primary reasons. It mentioned that the pursuit of Khalistan was the motivation for only 5% of “militants”.[46][47] The terrorists captured by the Indian Police had indicated a dominant criminal profile amongst them. Many terrorists were hard core criminals involved in major criminal cases before joining terrorism. Among the arrested terrorists were Harjinder Singh Jinda, who was a convicted bank robber and had escaped from prison, Devinder Singh Bai, a suspect in murder case and was Bhindranwale's close associate, and two drug smugglers, Upkar Singh and Bakshish Singh.[40]

According to Human Rights Watch in the beginning on the 1980s, Sikh separatists in Punjab attacked non-Sikhs in the state.[48] In October 1983, Sikh militants stopped a bus and shot six Hindu passengers. On the same day, in another location a group of militants killed two officials during an attack on a train.[21]:174 Trains were attacked and people were shot after being pulled from buses.

The Congress(I)-led Central Government dismissed its own Punjab's government, declaring a state of emergency, and imposed the President's Rule in the state. During the five months preceding Operation Blue Star, from 1 January 1984 to 3 June 1984, 298 people had been killed in various violent incidents across Punjab. In five days preceding the Operation, 48 people had been killed in the violence.[21]:175

Operation Bluestar

Operation Bluestar was an Indian military operation carried out between 1 and 8 June 1984, ordered by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to remove militant religious leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his armed followers from the buildings of the Harmandir Sahib complex in Amritsar, Punjab.[49] In July 1983, the Sikh political party Akali Dal's President Harcharan Singh Longowal had invited Bhindranwale to take up residence in Golden Temple Complex.[50][23] Bhindranwale later on made the sacred temple complex an armoury and headquarter,[51] for his armed uprising for Khalistan.[52] In the violent events leading up to the Operation Blue Star since the inception of Akali Dharm Yudh Morcha, the militants had killed 165 Hindus and Nirankaris. Even 39 Sikhs opposed to Bhindranwale were killed. The total number of deaths was 410 in violent incidents and riots while 1,180 people were injured.[53]

Counter Intelligence reports of the Indian agencies had reported that three prominent heads of the Khalistan movement Shabeg Singh, Balbier Singh and Amrik Singh had made at least six trips each to Pakistan between the years 1981 and 1983.[6] Intelligence Bureau reported that weapons training was being provided at gurdwaras in Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh. Soviet intelligence agency KGB reportedly tipped off the Indian agency RAW about the CIA and ISI working together on a Plan for Punjab with a code name "Gibraltar". RAW from its interrogation of a Pakistani Army officer received information that over a thousand trained Special Service Group commandos of the Pakistan Army had been dispatched by Pakistan into the Indian Punjab to assist Bhindranwale in his fight against the government. Large number of Pakistani agents also took the smuggling routes in the Kashmir and Kutch region of Gujarat, with plans to sabotage.[6]

On 1 June 1984 Indira Gandhi ordered the army to launch the Operation Blue Star.[54] A variety of army units along with paramilitary forces surrounded the temple complex on 3 June 1984. The army used the public address systems and loudspeakers to encourage the militants to surrender. Requests were also made to the militants to allow the trapped pilgrims to come out of the temple premises, before the clash with the army. However no surrender or release of pilgrims happened till 7 PM on 5 June.[55][55] The fighting started on 5 June with skirmishes and the battle went on for three days ending on 8 June. A clean-up operation codenamed as Operation Woodrose was also initiated throughout Punjab.[6]

The army had grossly underestimated the firepower possessed by the militants. Militants had Chinese made rocket-propelled grenade launchers with armour piercing capabilities. Tanks and heavy artillery were used to attack the militants using anti-tank and machine-gun fire from the heavily fortified Akal Takht. After a 24-hour firefight, the army finally wrested control of the temple complex. Casualty figures for the Army were 83 dead and 249 injured.[56] According to the official estimate presented by the Indian government, 1592 were apprehended and there were 493 combined militant and civilian casualties.[11] High civilian casualties were attributed to militants using pilgrims trapped inside the temple as human shields.[57]

Assassination of Indira Gandhi and anti-Sikh Riots

The Operation Bluestar was criticized by many Sikhs bodies, who interpreted the military action as an assault on Sikh religion.[58] Four months after the operation, on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi was assassinated in vengeance by her two Sikh bodyguards, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh.[23]

Public outcry over Gandhi's death led to the killings of more than 3,000 Sikhs in the ensuing 1984 anti-Sikh riots.[24] In the aftermath of the riots, the government reported that 20,000 had fled the city; the People's Union for Civil Liberties reported "at least" 1,000 displaced persons.[59] The most-affected regions were the Sikh neighbourhoods of Delhi. Human rights organisations and newspapers across India believed that the massacre was organised.[60][61][62] The collusion of political officials in the violence and judicial failure to penalise the perpetrators alienated Sikhs and increased support for the Khalistan movement.[63]

Rise in Sikh militancy

The Operation Blue Star and Anti-Sikh riots across Northern India were crucial events in evolution of the Khalistan movement. The extremist groups grew in numbers and strength.[6] The financial funding from the Sikh diaspora sharply increased and the Sikhs in US, UK and Canada donated thousands of dollars every week for the insurgency. Manbir Singh Chaheru the chief of Sikh militant group Khalistan Commando Force admitted that he had received more than $60,000 from Sikh organisations operating in Canada and Britain. One of the militant stated, "All we have to do is commit a violent act and the money for our cause increased drastically."[64] Indira Gandhi's son and political successor, Rajiv Gandhi, tried unsuccessfully to bring peace to Punjab.[51]

The opportunity that the government had after 1984 was lost and by March 1986, the Golden temple was back in control of extremist Sikh organisation Damdami Taksal.[6] By 1985, the situation in Punjab had become highly volatile. In December 1986, a bus was attacked by Sikh militants in which 24 Hindus were shot dead and 7 were injured and shot near Khuda in the Hoshiarpur district of Punjab.[65]

Weapons from Pakistan

By providing military support and modern sophisticated weapons to the Sikh extremists, the Pakistani ISI caused a large number of casualties in Punjab.[6] AK-47 provided by ISI was primarily used by the militants as an ideal weapon in their guerilla warfare, based on its superior performance in comparison to other weapons. While the Indian policemen fighting the militants had .303 Lee–Enfield rifles that were popular in the World war II and only a few of them had 7.62 1A self loading rifles. These weapons were outmatched by automatic AK-47s. Modern explosive arms were also supplied by the ISI. According to KPS Gill the terrorists mainly used crude bombs but since 1990s more modern explosives supplied by Pakistan had become widespread in usage among them. The number of casualties also increased with more explosives usage by the terrorists.[6]

A terrorist from Babbar Khalsa who had been arrested in early 1990s had informed Indian authorities about Pakistani ISI plans to use aeroplanes for Kamikaze attacks on Indian installations. The Sikhs however refused to participate in such operations on religious grounds as Sikhism prohibits suicide assassinations.[6] Between 1981 and 1984 the Sikh terrorists had undertaken several aircraft hijackings. In a hijacking in 1984 a German manufactured pistol was used and during the investigations, the German Intelligence Service BND confirmed that the weapon was part of a weapon consignment for Pakistani government. The American government had then issued warnings over the incident after which the series of hijackings of Indian aeroplanes had stopped.[6]

End of Violence

Between 1987 and 1991, Punjab was placed under an ineffective President's rule and was governed from Delhi. Elections were eventually held in 1992 but the voter turnout was poor. A new Congress(I) government was formed and it gave the police chief of the state K.P.S. Gill a free hand.

The extremist violence had started with targeting of the Nirankaris and followed by attack on the government machinery and the Hindus. Ultimately the Sikh terrorists also targeted other Sikhs with opposing viewpoints. This led to further loss of public support and the militants were eventually brought under control of law enforcement agencies by 1993.[26] Since 1993, the Punjab insurgency has petered out, with a last major incident being the Assassination of Chief Minister Beant Singh occurring in 1995.[6]

Timeline

| Date | Event | Source |

|---|---|---|

| March 1972 | Akalis routed in Punjab elections, Congress wins | |

| 17 October 1973 | Akalis ask for their rights through Anandpur Sahib Resolution | |

| 25 April 1980 | Gurbachan Singh of Sant Nirankari sect shot dead. | |

| 2 June 1980 | Akalis lose election in Punjab | [66] |

| 16 Aug 1981 | Sikhs in Golden Temple meet foreign correspndents | [67] |

| 9 Sep 1981 | Jagat Narain, Editor, Hind Samachar group murdered. | [68] |

| 29 Sep 1981 | Separatists killed on Indian Jetliner to Pakistan | [69] |

| 11 Feb 1982 | US gives Visa to Jagjit Singh Chauhan | [70] |

| 11 Apr 1982 | US Khalistani G.S. Dhillon Barred From India | [71] |

| July 1982 | Armed Sikh militants storm the parliament in a protest related to the deaths of 34 Sikhs in police custody | [72] |

| 4 Aug 1982 | Akalis demand autonomy and additional regions for Punjab | [73] |

| 11 Oct 1982 | Sikh stage protests at the Indian Parliament | [72] |

| Nov 1982 | Longowal threatens to disrupt Asian Games | [74] |

| 27 Feb 1983 | Sikhs permitted to carry daggers in domestic flights | [75] |

| 23 April 1983 | Punjab Police Deputy Inspector General A. S. Atwal was shot dead as he left the Harmandir Sahib compound by a gunman from Bhindranwale's group | [34] |

| 3 May 1983 | Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, talks of violence being perpetuated against Sikhs and for India to understand | [76] |

| 18 June 1983 | A detective Inspector from Punjab police killed by Sikh militants | [77] |

| 14 July 1983 | Four policemen killed by Sikh militants | [77] |

| 21 September 1983 | Senior superintendent of Police wounded and his guard killed Sikh militants | [77] |

| 29 September 1983 | 5 Police constables killed by Sikh militants in a week since 22 | [77] |

| 14 Oct 1983 | 3 people killed at a Hindu festival in Chandigarh | [78] |

| 5 Oct 1983 | 6 Hindu passengers killed in 1983 Dhilwan bus massacre | [79][77] |

| 6 Oct 1983 | President's rule imposed in Punjab | [77] |

| Oct 1983 | Hindus pulled off a train and bus and killed | [80] |

| 21 Oct 1983 | A passenger trained was derailed and 19 agricultural labourers travelling were killed by Sikh militants | [77] |

| 18 Nov 1983 | A bus was hijacked and 4 Hindu passengers were killed by Sikh militants | [77] |

| 9 Feb 1984 | A wedding procession bombed | [81] |

| 14 Feb 1984 | Six policemen abducted from a post near Golden Temple and one of them killed by Bhindranwale's men | [34] |

| 14 Feb 1984 | More than 12 people killed in Sikh - Hindu riots in Punjab and Haryana | [77] |

| 19 Feb 1984 | Sikh-Hindu clashes spread in North India | [82] |

| 23 Feb 1984 | 11 Hindus killed and 24 injured by Sikh militants | [83] |

| 25 Feb 1984 | 6 Hindus killed in by Sikh militants, total 68 people killed over last 11 days | [84] |

| 29 Feb 1984 | By this time, the Temple had become the centre of the 19-month-old uprising by the separatist Sikhs | [85] |

| 28 March 1984 | Harbans Singh Manchanda, the Delhi Sikh Gurudwara Management Committee (DSGMC) president murdered. He had demanded ouster of Bhindranwale from Akal Takht few days back | [86] |

| 3 April 1984 | Militants cause fear and instability in Punjab | [87] |

| 8 April 1984 | Longowal writes – he cannot control Bhindranwale anymore | [88] |

| 14 April 1984 | Surinder Singh Sodhi, follower of Bhindranwale shot dead at the temple by a man and a women | [89] |

| 17 April 1984 | Deaths of 3 Sikh Activists in factional fighting | [90] |

| 27 May 1984 | Ferosepur politician killed after confessing to fake police encounters with "terrorist" killings | [91] |

| 2 June 1984 | Total media and the press black out in Punjab, the rail, road and air services in Punjab suspended. Foreigners' and NRIs' entry was also banned and water and electricity supply cut off. | [92][93][94] |

| 3 June 1984 | Army takes controls Punjab's security | [95] |

| 5 June 1984 | Operation Blue Star to remove militants from Harmandir Sahib commences, Punjab shut-down from outside world. | [96] |

| 6 June 1984 | Daylong battle in temple | [97][98] |

| 7 June 1984 | Harmandir Sahib over taken by army | [99] |

| 7 June 1984 | Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale dead | [100] |

| 8 June 1984 | 27 Sikhs killed in protests in Srinagar, Ludhiana, Amritsar after Government forces fired on protesters | [101] |

| 9 June 1984 | Weapons seized, troops fired on | [102] |

| 10 June 1984 | Reports of anti-Sikh riots and killings in Delhi | [103] |

| 11 June 1984 | Negotiators close to a settlement on waters | [104] |

| 24 August 1984 | 7 Sikh terrorists abduct 100 passengers in 1984 Indian Airlines Airbus A300 hijacking | [105] |

| 31 October 1984 | Indira Gandhi assassinated | [106] |

| 1 November 1984 | 1984 anti-Sikh riots begin in Delhi | [60] |

| 3 November 1984 | Anti Sikh Violence a total of 2,733 Sikhs were killed | [60] |

| 23 June 1985 | Air India Flight 182 was bombed by Sikh terrorists killing 329 people (including 22 crew members); almost all of them Hindus | |

| 20 August 1985 | Harcharan Singh Longowal assassinated | [107] |

| 29 September 1985 | 60% vote, Akali Dal won 73 of 115 seats, Barnala CM | [108] |

| 26 January 1986 | Sikhs have a global meeting and the rebuilding of Akal Takht declared as well as the five member Panthic Committee selected and have draft of the Constitution of Khalistan written | [109] |

| 29 April 1986 | Resolution of Khalistan passed by Sarbat Khalsa and Khalistan Commando Force also formed at Akal Takht with more than 80,000 Sikhs present. | [110] |

| 25 July 1986 | 14 Hindus and one Sikh passenger killed in the 1986 Muktsar Bus massacre by Sikh terrorists | [111] |

| 30 November 1986 | 24 Hindu passengers killed in the 1986 Hoshiarpur Bus massacre by Sikh terrorists | [112] |

| 19 May 1987 | State Committee Member CPI(M) Comrade Deepak Dhawan was murdered at Village Sangha, Tarn Taran | [113] |

| 7 July 1987 | Sikh terrorists from Khalistan Commando Force attacked two buses. They singled out and killed 34 Hindu bus passengers in 1987 Haryana killings | [114] |

| 12 May 1988 | Operation Black Thunder II to remove militants from Harmandir Sahib | [115] |

| 10 January 1990 | Senior Superintendent of Batala Police Gobind Ram killed in bomb blast in retaliation of police gang raping Sikh woman of Gora Choor village | [116][117] |

| 16 June 1991 | 80 people killed on two trains by extremists | [118] |

| 17 October 1991 | 1991 Rudrapur bombings | |

| 25 February 1992 | Congress sweeps Punjab Assembly elections | [119] |

| 7 January 1993 | Punjab's Biggest encounter done in village Chhichhrewal Tehsil Batala, 11 terrorists were encountered | |

| 3 September 1995 | CM Beant Singh killed in bomb blast | [121] |

See also

- 1984 Anti-Sikh riots

- Operation Blue Star

- Khalistan

- 1991 Punjab killings

- 1987 Punjab killings

- List of Victims of Terrorism in Indian Punjab

References

- Gates, Scott; Roy, Kaushik (17 February 2016). "Unconventional Warfare in South Asia: Shadow Warriors and Counterinsurgency". Routledge. p. 163. Retrieved 10 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- "SAS involvement in Punjab insurgency, says experts". Kim Sengupta. The Independent. 15 January 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Brar, K.S. (July 1993). Operation Blue Star: the true story. UBS Publishers' Distributors. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-81-85944-29-6.

- Dogra, Cander Suta. "Operation Blue Star - the Untold Story". The Hindu, 10 June 2013. Web. 9 Aug 2013.

- Cynthia Keppley Mahmood (1 January 2011). Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Defenders. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. Title, 91, 21, 200, 77, 19. ISBN 978-0-8122-0017-1. Retrieved 9 August 2013

- Kiessling, Hein (2016). Faith, Unity, Discipline: The Inter-Service-Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849048637. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Martin 2013, p. 190.

- "Pakistan supporting Sikh militants, say fresh intelligence inputs". Hindustan Times. 2 September 2017.

- "Punjab Military Conflict" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 12 December 2000. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- "Operation Bluestar". DNA. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- White Paper on the Punjab Agitation. Shiromani Akali Dal and Government of India. 1984. p. 169. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- "The Official Home Page of the Indian Army". Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- "Punjab Militant attacks". One India. 27 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007). Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. Pearson Education India. p. 484. ISBN 9788131708347. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Mahmood, Cynthia Keppley (1996). Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780812215922. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Singh, Khushwant. "The Anandpur Sahib Resolution and Other Akali Demands". oxfordscholarship.com/. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- Giorgio Shani (2008). Sikh nationalism and identity in a global age. Routledge. pp. 51–60. ISBN 978-0-415-42190-4.

- Joshi, Chand, Bhindranwale: Myth and Reality (New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1984), p. 129.

- Crenshaw, Martha (1 November 2010). Terrorism in Context. Penn State Press. p. 381. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Muni, S. D. (2006). Responding to Terrorism in South Asia. Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 2006. p. 36. ISBN 9788173046711. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Robert L. Hardgrave; Stanley A. Kochanek (2008). India: Government and Politics in a Developing Nation. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-00749-4. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- June 15, Asit Jolly; June 25, 2012 ISSUE DATE:; June 24, 2012UPDATED:; Ist, 2012 15:45. "The Man Who Saw Bhindranwale Dead: Col Gurinder Singh Ghuman". India Today. Retrieved 13 February 2020.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Operation Blue Star: India's first tryst with militant extremism - Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". Dnaindia.com. 5 November 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- Singh, Pritam (2008). Federalism, Nationalism and Development: India and the Punjab Economy. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-415-45666-1. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- Documentation, Information and Research Branch, Immigration and Refugee Board, DIRB-IRB. India: Information from four specialists on the Punjab, Response to Information Request #IND26376.EX, 17 February 1997 (Ottawa, Canada).

- "Why Osama resembles Bhindranwale". Rediff News. 9 June 2004. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Singh, Atamjit. "The Language Divide in Punjab". South Asian Graduate Research Journal, Volume 4, No. 1, Spring 1997. Apna. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Sumit Ganguly; Larry Diamond; Marc F. Plattner (13 August 2007). The State of India's Democracy. JHU Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8018-8791-8. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Alvin William Wolfe; Honggang Yang (1996). Anthropological Contributions to Conflict Resolution. University of Georgia Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8203-1765-6. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Akshayakumar Ramanlal Desai (1 January 1991). Expanding Governmental Lawlessness and Organized Struggles. Popular Prakashan. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-81-7154-529-2.

- "34 Years On, A Brief History About Operation Bluestar, And Why It Was Carried Out". NDTV. 6 June 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Mahmood, Cynthia Keppley (1996). Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780812215922. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Guha, Ramachandra (2008). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy (illustrated, reprint ed.). Excerpts: Macmillan. ISBN 9780330396110. Retrieved 10 July 2018.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Gill, Kanwar Pal Singh (1997). Punjab, the Knights of Falsehood. Har-Anand Publications.

- Mahmood, Cynthia Keppley (1996). Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780812215922. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Cynthia Keppley Mahmood, Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996, pp. 58–60; Gopal Singh, A History of the Sikh People, New Delhi, World Book Center, 1988, p. 739.

- Singh (1999), pp. 365–66.

- Gill, K.P.S. and Khosla, S (2017). Punjab: The Enemies Within : Travails of a Wounded Land Riddled with Toxins. Excerpt: Bookwise (India) Pvt. Limited. ISBN 9788187330660.CS1 maint: location (link)

- India in 1984: Confrontation, Assassination, and Succession, by Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr. Asian Survey, 1985 University of California Press

- "Pakistan involvement in Sikh terrorism in Punjab based on solid evidence: India". India Today. 15 May 1986. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Sirrs, Owen L. (2016). Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert Action and Internal Operations. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 9781317196099. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "Operation Bluestar". India Today. 1999.

- "Pakistan's Involvement in Terrorism against India".

- "CIA, ISI encouraged Sikh terrorism: Ex-R&AW official". Rediff News. 26 July 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- J. C. Aggarwal; S. P. Agrawal (1992). Modern History of Punjab. Concept Publishing Company. p. 117. ISBN 978-81-7022-431-0. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- Puri et al., Terrorism in Punjab, pp. 68–71

- Van Dyke 2009, p. 991.

- "India: Time to Deliver Justice for Atrocities in Punjab (Human Rights Watch, 18-10-2007)".

- Swami, Praveen (16 January 2014). "RAW chief consulted MI6 in build-up to Operation Bluestar". Chennai, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Volume II: 1839-2004, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 337.

- "Sikh Leader in Punjab Accord Assassinated". LA Times. Times Wire Services. 21 August 1985. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Operation Bluestar, 5 June 1984 Archived 8 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Mark Tully, Satish Jacob (1985). "deaths+in+violent" Amritsar; Mrs. Gandhi's Last Battle (e-book ed.). London. p. 147, Ch. 11.

- Wolpert, Stanley A., ed. (2009). "India". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Amberish K Diwanji (4 June 2004). "'There is a limit to how much a country can take'". The Rediff Interview/Lieutenant General Kuldip Singh Brar (retired). Rediff.com. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- "Army reveals startling facts on Bluestar". Tribune India. 30 May 1984. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Kiss, Peter A. (2014). Winning Wars amongst the People: Case Studies in Asymmetric Conflict (Illustrated ed.). Potomac Books. p. 100. ISBN 9781612347004. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Westerlund, David (1996). Questioning The Secular State: The Worldwide Resurgence of Religion in Politics. C. Hurst & Co. p. 1276. ISBN 1-85065-241-4.

- Mukhoty, Gobinda; Kothari, Rajni (1984), Who are the Guilty ?, People's Union for Civil Liberties, retrieved 4 November 2010

- Bedi, Rahul (1 November 2009). "Indira Gandhi's death remembered". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

The 25th anniversary of Indira Gandhi's assassination revives stark memories of some 3,000 Sikhs killed brutally in the orderly pogrom that followed her killing

- "1984 anti-Sikh riots backed by Govt, police: CBI". IBN Live. 23 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Swadesh Bahadur Singh (editor of the Sher-i-Panjâb weekly): "Cabinet berth for a Sikh", The Indian Express, 31 May 1996.

- Watch/Asia, Human Rights; (U.S.), Physicians for Human Rights (May 1994). Dead silence: the legacy of human rights abuses in Punjab. Human Rights Watch. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-56432-130-5. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- Pruthi, Raj (2004). Sikhism and Indian Civilization. Discovery Publishing House. p. 162. ISBN 9788171418794. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Tempest, Rone (1 December 1986). "Sikh Gunmen Kill 24 Hindus, Wound 7 on Punjab Bus". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Mrs. Gandhi's Party Wins Easily In 8 of 9 States Holding Elections, The New York Times, 3 June 1980

- IN INDIA, SIKHS RAISE A CRY FOR INDEPENDENT NATION, MICHAEL T. KAUFMAN, THE NEW YORK TIMES, 16 August 1981

- GUNMEN SHOOT OFFICIAL IN A TROUBLED INDIAN STATE, THE NEW YORK TIMES, 18 October 1981

- Sikh Separatists murdered on Indian Jetliner to Pakistan, MICHAEL T. KAUFMAN, The New York Times 30 September 1981

- Two Visa Disputes Annoy and Intrigue India, MICHAEL T. KAUFMAN, The New York Times, 11 February 1982

- Sikh Separatist Is Barred From Visiting India, The New York Times, 11 April 1982

- ANGRY SIKHS STORM INDIA'S ASSEMBLY BUILDING, WILLIAM K. STEVENS, THE NEW YORK TIMES, 12 October 1982

- The Sikh Diaspora: The Search for Statehood By Darshan Singh Tatla

- Sikhs Raise the Ante at A Perilous Cost to India, WILLIAM K. STEVENS, The New York Times, 7 November 1982

- Concessions Granted to Sikhs By Mrs. Gandhi's Government, The New York Times, 28 February 1983

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F6071FF73E5C0C708CDDAC0894DB484D81&scp=8&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt SIKH HOLY LEADER TALKS OF VIOLENCE, WILLIAM K. STEVENSS, The New York Times, 3 May 1983

- Jeffrey, Robin (2016). What’s Happening to India?: Punjab, Ethnic Conflict, and the Test for Federalism (2, Illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 167. ISBN 9781349234103. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- Mrs. Gandhi Says Terrorism Will Fail, WILLIAM K. STEVENS, The New York Times, 16 October 1983

- INDIAN GOVERNMENT TAKES OVER A STATE SWEPT BY RELIGIOUS STRIFE, WILLIAM K. STEVENS, 7 October 1983

- 11 PEOPLE KILLED IN PUNJAB UNREST, WILLIAM K. STEVENS, The New York Times, 23 February 1984

- General Strike Disrupts Punjab By SANJOY HAZARIKA, The New York Times, 9 February 1984;

- Sikh-Hindu Clashes Spread in North India, The New York Times, 19 February 1984

- "11 HINDUS KILLED IN PUNJAB UNREST". New York Times. 23 February 1984. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Sikh-Hindu Violence Claims 6 More Lives". New York Times. 25 February 1984. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10C17FE3F5D0C7A8EDDAB0894DC484D81&scp=14&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt Sikh Temple: Words of Worship, Talk of Warfare, The New York Times, 29 February 1984

- "DSGMC president Harbans Singh Manchanda murder in Delhi sends security forces in a tizzy". India Today. 30 April 1984. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- Stevens, William K. (3 April 1984). "With Punjab the Prize, Sikh Militants Spread Terror". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- SIKH WARNS NEW DELHI ABOUT PUNJAB STRIFE, The New York Times, 8 April 1984

- "Around the World". The New York Times. 15 April 1984. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- 3 Sikh Activists Killed In Factional Fighting, The New York Times, 17 April 1984

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40616FE3F5F0C748EDDAC0894DC484D81&scp=22&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt 5 MORE DIE IN CONTINUING INDIAN UNREST, The New York Times, 17 April 1984

- Hamlyn, Michael (6 June 1984). "Journalists removed from Amritsar: Army prepares to enter Sikh shrine". The Times. p. 36.

- Tully, Mark (1985). Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi's Last Battle. Jonathan Cape.

- "Gun battle rages in Sikh holy shrine". The Times. 5 June 1984. p. 1.

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FB0A11FB3E5F0C708CDDAF0894DC484D81&scp=9&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt INDIAN ARMY TAKES OVER SECURITY IN PUNJAB AS NEW VIOLENCE FLARES, The New York Times, 3 June 1984

- HEAVY FIGHTING REPORTED AT SHRINE IN PUNJAB, The New York Times, 5 June 1984

- Stevens, William K.; Times, Special To the New York (6 June 1984). "Indians Report Daylong Battle at Sikh Temple". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Correcting Previous Statement on Golden Temple". Congressional Record – Senate (US Government). 17 June 2004. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70914FB395F0C748CDDAF0894DC484D81&scp=3&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt 308 PEOPLE KILLED AS INDIAN TROOPS TAKE SIKH TEMPLE, The New York Times, 7 June 1984

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50A1FF8395F0C7B8CDDAF0894DC484D81&scp=2&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt, SIKH CHIEFS: FUNDAMENTALIST PRIEST, FIREBRAND STUDENT AND EX-GENERAL New York Times, 8 June 1984

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10D11F9395F0C7B8CDDAF0894DC484D81&scp=4&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt SIKHS PROTESTING RAID ON SHRINE; 27 DIE IN RIOTS, The New York Times, 8 June 1984

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10D11F9395F0C7B8CDDAF0894DC484D81&scp=4&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt SIKHS IN TEMPLE HOLD OUT: MORE VIOLENCE IS REPORTED; 27 DIE IN RIOTS, The New York Times, 9 June 1984

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10911FE385F0C738DDDAF0894DC484D81&scp=8&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt INDIAN GOVERNMENT TAKES ON SIKHS IN A BLOODY ENCOUNTER, The New York Times, 10 June 1984

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F00B14FB385F0C718DDDAF0894DC484D81&scp=4&sq=Bhindranwale&st=nyt, The New York Times, 12 June 1984

- "INDIAN JET CARRYING Z264 HIJACKED TO PAKISTAN, REPORTEDLY BY SIKHS". New York Times. 1984. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F1091FFF385D0C728CDDA80994DC484D81&scp=5&sq=Indira+gandhi+killed&st=nyt, GANDHI, SLAIN, IS SUCCEEDED BY SON; KILLING LAID TO 2 SIKH BODYGUARDS New York Times, 1 November 1984

- Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab, By Harnik Deol, Routledge, 2000

- Freudenheim, Milt; Levine, Richard; Giniger, Henry (29 September 1985). "THE WORLD; Gandhi Hails A Loss in Punjab". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- Tatla, Darsham (2009). The Sikh Diaspora: The Search For Statehood. London: Routledge. p. 277. ISBN 9781135367442.

- Mandair, Arvind-Pal (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. p. 103. ISBN 9781441102317.

- Tempest, Rone (26 July 1986). "Suspected Sikh Terrorists Kill 15 on India Bus". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "TEMPLE SIKH EXTREMISTS HIJACK PUNJAB BUS AND KILL 24 PEOPLE". The New York Times. 1 December 1986. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Deepak Dhawan gunned down by Extremists. Institute for Defence Studies. 1987. p. 987,994.

- Hazarika, Sanjoy (8 July 1987). "34 Hindus Killed in New Bus Raids; Sikhs Suspected". New York Times. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Singh, Sarabjit (2002). Operation Black Thunder: An Eyewitness Account of Terrorism in Punjab. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9780761995968.

- Mahmood, Cynthia (2011). Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780812200171.

- Ghosh, S. K. (1995). Terrorism, World Under Siege. New Delhi: APH Publishing. p. 469. ISBN 9788170246657.

- Crossette, Barbara (16 June 1991). "Extremists in India Kill 80 on 2 Trains As Voting Nears End". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- The Punjab Elections 1992: Breakthrough or Breakdown? Gurharpal Singh, Asian Survey, Vol. 32, No. 11 (Nov. 1992), pp. 988–999 JSTOR 2645266

- Gurharpal Singh, Asian Survey, Vol. 32, No. 11 (Nov. 1992), pp. 988–999 JSTOR 2645266

- Burns, John F. (3 September 1995). "Assassination Reminds India That Sikh Revolt Is Still a Threat". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Sources

Bibliography

- The Punjab Mass Cremations Case: India Burning the Rule of Law (PDF). Ensaaf. January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- Kaur, Jaskaran; Sukhman Dhami (October 2007). "Protecting the Killers: A Policy of Impunity in Punjab, India" (PDF). 19 (14). New York: Human Rights Watch. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lewis, Mie; Kaur, Jaskaran (5 October 2005). Punjab Police: Fabricating Terrorism Through Illegal Detention and Torture (PDF). Santa Clara: Ensaaf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- Martin, Gus (2013), Understanding Terrorism: Challenges, Perspectives, and Issues, Sage, p. 174, ISBN 978-1-4522-0582-3

- Silva, Romesh; Marwaha, Jasmine; Klingner, Jeff (26 January 2009). Violent Deaths and Enforced Disappearances During the Counterinsurgency in Punjab, India: A Preliminary Quantitative Analysis (PDF). Palo Alto: Ensaaf and the Benetech Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- Cry, the beloved Punjab: a harvest of tragedy and terrorism, by Darshan Singh Maini. Published by Siddharth Publications, 1987.

- Genesis of terrorism: an analytical study of Punjab terrorists, by Satyapal Dang. Published by Patriot, 1988.

- Combating Terrorism in Punjab: Indian Democracy in Crisis, by Manoj Joshi. Published by Research Institute for the Study of Conflict and Terrorism, 1993.

- Politics of terrorism in India: the case of Punjab, by Sharda Jain. Published by Deep & Deep Publications, 1995. ISBN 81-7100-807-0.

- Terrorism: Punjab's recurring nightmare, by Gurpreet Singh, Gourav Jaswal. Published by Sehgal Book Distributors, 1996.

- Terrorism in Punjab: understanding grassroots reality, by Harish K. Puri, Paramjit S. Judge, Jagrup Singh Sekhon. Published by Har-Anand Publications, 1999.

- Terrorism in Punjab, by Satyapal Dang, V. D. Chopra, Ravi M. Bakaya. Published by Gyan Books, 2000. ISBN 81-212-0659-6.

- Rise and Fall of Punjab Terrorism, 1978–1993, by Kalyan Rudra. Published by Bright Law House, 2005. ISBN 81-85524-96-3.

- The Long Walk Home, by Manreet Sodhi Someshwar. Harper Collins, 2009.

- Global secutiy net 2010, Knights of Falsehood by KPS Gill, 1997