Croats of Serbia

Flag of National Council of Croat Minority in Serbia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 57,900 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 47,033 | |

| 7,752 | |

| Languages | |

| Croatian and Serbian | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bunjevci, Šokci | |

| Part of a series on |

| Croats |

|---|

|

|

Subgroups |

The Croats of Serbia (Croatian: Hrvati u Srbiji, Serbian: Хрвати у Србији / Hrvati u Srbiji) or Serbian Croats (Croatian: Srpski Hrvati, Serbian: Српски Хрвати / Srpski Hrvati) are the recognized Croat national minority in Serbia, a status they received in 2002.[1] According to the 2011 census, there were 57,900 Croats in Serbia or 0.8% of the region's population.[2] Of these, 47,033 lived in Vojvodina, where they formed the fourth largest ethnic group, representing 2.8% of the population. A further 7,752 lived in the national capital Belgrade, with the remaining 3,115 in the rest of the country.

History

During the 15th century, Croats mostly lived in the Syrmia region. It is estimated that they were a majority in 76 out of 801 villages that existed in the present-day territory of Vojvodina.[3] During the 17th century, Roman Catholic Bunjevci from Dalmatia migrated to Vojvodina, where Šokci had already been living. According to some opinions, Šokci might be descendants of medieval Slavic population of Vojvodina where their ancestors might lived since the 8th century. According to other opinions, medieval Slavs of Vojvodina mainly spoke ikavian dialect, which is today rather associated with standard Croatian. Between 1689, when the Habsburg Monarchy conquered parts of Vojvodina, and the end of the 19th century, a small number of Croats from Croatia also migrated to the region.

Before the 20th century, most of the Bunjevac and Šokac populations living in Habsburg Monarchy haven't been nationally awakened yet. Some of their leaders (like Ivan Antunović, Blaško Rajić, Petar Pekić, Pajo Kujundžić, Mijo Mandić, Lajčo Budanović, Stipan Vojnić Tunić, Vranje Sudarević, etc.) worked hardly to awake their Croatian or Yugoslav national feelings.

According to 1851 data, it is estimated that the population of the Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar, the historical province that was predecessor of present-day Vojvodina, included, among other ethnic groups, 62,936 Bunjevci and Šokci and 2,860 Croats.[4] Subsequent statistical estimations from the second half of the 19th century (conducted during Austro-Hungarian period) counted Bunjevci and Šokci as "others" and presented them separately from Croats (in 1910 Austro-Hungarian census, 70,000 Bunjevci were categorized as "others").[5]

The 1910 Austro-Hungarian census also showed large differences in the numbers of those who considered themselves Bunjevci and Šokci, and those who considered themselves Croats. According to the census, in the city of Subotica there were only 39 citizens who declared Croatian as their native language, while 33,390 citizens were listed as speakers of "other languages" (most of them declared Bunjevac as their native language).[6] In the city of Sombor, 83 citizens declared Croatian language, while 6,289 citizens were listed as speakers of "other languages" (mostly Bunjevac).[7] In the municipality of Apatin, 44 citizens declared Croatian and 7,191 declared "other languages" (mostly Bunjevac, Šokac and Gypsy).[6]

In Syrmia, which was then part of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, according to the 1910 census results[8] Croats were a relative or absolute majority in Gibarac (843 Croats or 86.46% out of total population), Kukujevci (1,775 or 77.61%), Novi Slankamen (2,450 or 59.22%), Petrovaradin (3,266 or 57.02%), Stari Slankamen (466 or 48.19%), Hrtkovci (1,144 or 45.43% ) and Morović (966 or 41.67%). Other places which had a significant minority of Croats included Novi Banovci (37.70%), Golubinci (36.86%), Sremska Kamenica (36.41%), Sot (33.01%), Sremska Mitrovica (30.32%), Sremski Karlovci (29.94%) and Ljuba (29.86%).

In 1925, Bunjevac-Šokac Party and Pučka kasina organized in Subotica the 1000th anniversary celebration of the establishment of Kingdom of Croatia, when in 925 Tomislav of Croatia became first king of the Croatian Kingdom. On the King Tomislav Square in Subotica a memorial plaque was unveiled with the inscription "The memorial plaque of millennium of Croatian Kingdom 925-1925. Set by Bunjevci Croats".[9] Besides Subotica, memorial plaques of King Tomislav were also revealed in Sremski Karlovci and Petrovaradin.

In 1990s, during the war in Croatia, members of Serbian Radical Party organized and participated in the expulsion of the Croats in some places in Vojvodina. The President of the Serbian Radical Party, Vojislav Šešelj is indicted for participation in these events.[10] According to some estimations, the number of Croats which have left Serbia under political pressure of the Milošević's regime might be between 20,000 and 40,000.[11]

Demographics

The number of Croats in Serbia was somewhat larger in previous censuses that were conducted between 1948 and 1991. However, the real number of declared Croats in the time when these censuses were conducted may have been smaller because the communist authorities counted those citizens who declared themselves Bunjevci or Šokci as Croats. Today, most members of the Šokci community consider themselves Croats, while large part of the Bunjevci population see themselves as members of the distinct Bunjevci ethnicity, while smaller part sees themselves as Croats.

The largest recorded number of Croats in a census was in 1961 when there were 196,409 Croats (including Bunjevci and Šokci) in the Socialist Republic of Serbia (around 2.57% of the total population of Serbia at the time). Since 1961 census, the Croat population in Serbia is in a constant decrease. This is caused by various reasons, including economic emigration, and ethnic tensions of the Yugoslav wars during the 1990s, more specifically the 1991-1995 War in Croatia.[12] During this war-time period, Croats in Serbia were under pressure from the Serbian Radical Party[13][14] and some Serb refugees from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to move to Croatia. In that time, a transfer of population occurred between Croats from Serbia and Serbs from Croatia.[15][16] Based on an investigation by the Humanitarian Law Fund from Belgrade in the course of June, July, and August 1992, more than 10,000 Croats from Vojvodina exchanged their property for the property of Serbs from Croatia, and altogether about 20,000 Croats left Serbia.[17] According to Petar Kuntić of Democratic Alliance of Croats in Vojvodina, 50,000 Croats moved out from Serbia during the Yugoslav wars.[18][19]

| Year | Croats | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 169,864 | 2.6% |

| 1953 | 173,246 | 2.4% |

| 1961 | 196,409 | 2.5% |

| 1971 | 184,913 | 2.1% |

| 1981 | 149,368 | 1.6% |

| 1991 | 105,406 | 1.0% |

| 1991* | 97,344 | 1.2% |

| 2002* | 70,602 | 0.9% |

| 2011* | 57,900 | 0.8% |

* - excluding Kosovo

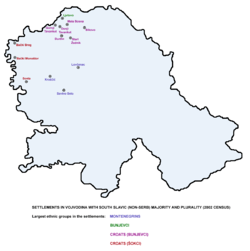

Croats in Vojvodina

Croats are the fourth largest ethnic group in the Vojvodina province. According to the 2011 census, there are 47,033 Croats living in Vojvodina.[20] The Croatian language is one of the official languages of provincial administration of Vojvodina.

About two thirds of all Croats in Vojvodina have Bunjevci or Šokci origins.[21] Those of Bunjevci origin constituting the largest part of population in several villages in the Subotica municipality: Bikovo, Gornji Tavankut, Donji Tavankut, Đurđin, Mala Bosna, Ljutovo and Stari Žednik.

Croats of Šokci origin constituting the largest part of population in three villages: Sonta (in the municipality of Apatin), Bački Breg and Bački Monoštor (both in the municipality of Sombor).[22]

| Year | Croats | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1495 | 7,500 | 3.9% |

| 1787 | 38,161 | 8.0% |

| 1828 | 67,692 | 7.8% |

| 1840 | 66,362 | 7.3% |

| 1857 | 60,690 | 5.9% |

| 1880 | 72,298 | 6.1% |

| 1890 | 80,404 | 6.0% |

| 1900 | 81,198 | 5.7% |

| 1910 | 91,366 | 6.0% |

| 1921 | 129,788 | 8.5% |

| 1931 | 132,517 | 8.2% |

| 1940 | 101,035 | 6.1% |

| 1948 | 134,232 | 8.1% |

| 1953 | 128,054 | 7.5% |

| 1961 | 145,341 | 7.8% |

| 1971 | 138,561 | 7.1% |

| 1981 | 109,203 | 5.4% |

| 1991 | 74,226 | 3.7% |

| 2002 | 56,546 | 2.7% |

| 2011 | 47,033 | 2.4% |

source:[23]

note1: The numbers were adjusted for the present borders of Vojvodina.

note2: Croats are counted together with Bunjevci and Šokci for data before 1991.

Politics

The Croats of Serbia are politically represented by several political parties, including: Democratic League of Croats in Vojvodina, Demokratska zajednica Hrvata (Democratic Union of Croats), Hrvatska bunjevačko-šokačka stranka (Croatian Bunjevac-Šokac Party), Hrvatski narodni savez (Croatian national alliance) and Hrvatska srijemska inicijativa (Croatian Syrmian Initiative).

The Croat National Council is, according to its Statute, a body of self-government of Croat minority in Serbia. On 11 June 2005 the Council adopted the historical coat of arms of Croatia, a checkerboard consisting of 13 red and 12 white fields (the difference with the Croatian coat of arms being the crown on top).[24]

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of Croats of Serbia is one of the symbols of the Croatian minority in Serbia. The coat of arms of Croats of Serbia is actually the historical coat of arms of Croatia. It is a checkerboard (Croatian: Šahovnica) that consists of 13 red and 12 white fields. The difference between this coat of arms and the coat of arms of Croatia is in the crown on top, which this coat of arms does not have, but the coat of arms of Croatia has.[25] It is situated on the center of flag of Croats of Serbia.

Flag and coat of arms of Croats of Serbia were adopted on 11 June 2005 in a session of the Croat National Council, in Subotica.[25]

Organizations

- Institute for Culture of Croats of Vojvodina

- Croatian Community in Belgrade “Tin Ujević”

Notable people

- Marijan Beneš, former boxer born in Belgrade to a Croat father and a Serb mother

- Ivan Ćurković, football player and President of the Olympic Committee of Serbia

- Novak Djoković, professional tennis player, born in Belgrade to a Serb father and a Croat mother

- Ivana Dulić-Marković, Deputy Prime Minister of Serbia and Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management

- Oliver Dulić, politician with Bunjevac Croat ancestry

- Stjepan Filipović, People's Hero of Yugoslavia

- Josip Jelačić, Ban of Croatia

- Mirna Jukić, Austrian swimmer

- Josip Leko, Speaker of the Croatian Parliament

- Franjo Mihalić, long-distance runner and Olympic silver medalist

- Jovan Mikić Spartak, triple jumper

- Slavoljub Muslin, former football expert

- Ilija Okrugić, poet and play wright

- Marko Penov, woodcarver of Croat descent

- Ratko Rudić, water polo coach and a former water polo player

- Franko Simatović, head of Slobodan Milošević's secret police

- Marko Šimić, Croatian footballer born in Valjevo

- Vanja Udovičić, politician and a former water polo player born in Belgrade to a Croat father and a Serb mother

- Ivica Vrdoljak, Croatian football player

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Hrvatska manjina u Republici Srbiji". rs.mvp.hr (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Republic of Croatia. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ "Official Census 2011 Results". Republički zavod za statistiku. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Károly Kocsis, Saša Kicošev: Changing ethnic patterns on the present territory of Vojvodina

- ↑ Dr Dušan J. Popović, Srbi u Vojvodini, knjiga 3, Novi Sad, 1990.

- ↑ Juraj Lončarević: Hrvati u Mađarskoj i Trianonski ugovor, Školske novine, Zagreb, 1993, ISBN 953-160-004-X

- 1 2

- ↑ http://www.talmamedia.com/php/district/district.php?county=B%E1cs-Bodrog

- ↑ A magyar szent korona országainak 1910. évi népszámlálása; Budapest 1912

- ↑ Mario Bara: Hrvatska seljačka stranka u narodnom preporodu bačkih Hrvata (The Croatian Pesants Party in the national movement of Bačka Croats), p. 63

- ↑ Vojislav Seselj indictment

- ↑ Hrvatska nacionalna manjina u Srbiji Archived March 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (in Croatian) Pismo prognanih Hrvata Josipoviću

- ↑ July 13, 1992 Vreme News Digest Agency No 42, Hrtkovci, The Moving Out Continues, by Jasmina Teodosijevic

- ↑ Serbia Facing Chauvinism Again, Awakening of rats

- ↑ (in Croatian) Oko stotinu protjeranih Hrvata iz Vojvodine stiglo u Hrvatsku 10 August 1995

- ↑ (in Croatian) Dom i svijet - Broj 220, Kako su Hrvati protjerani iz Vojvodine bolji zivot pronasli u Hrvatskoj, Hrtkovci u Slavoniji

- ↑ Croats in Serbia which is not in war with Croatia, With head stuck into sand

- ↑ (in Serbian) Sedamnaest godina od proterivanja Hrvata iz Hrtkovaca, Zoran Glavonjić

- ↑ "Anniversary of SRS rally in Vojvodina town". Archived from the original on 2010-05-10. Retrieved 2011-05-01.

- ↑ Republički zavod za statistiku Republike Srbije

- ↑ Lazo M. Kostić, Vojvodina i njene manjine, Novi Sad, 1999.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva, domaćinstva i stanova u 2002, Stanovništvo - nacionalna ili etnička pripadnost, podaci po naseljima, knjiga 1, Republički zavod za statistiku, Beograd, Februar 2003.

- ↑ Tóth Antal: Magyarország és a Kárpát-medence regionális társadalomföldrajza, 2011, p. 67-68

- ↑ http://www.hnv.org.rs/obiljezja.php (in Croatian)

- 1 2 http://www.hnv.org.rs/obiljezja.php (in Croatian)

References

- (PDF, English)

- Croats in Vojvodina

- (in Croatian) Hrvati Bunjevci traže da se prekinu podjele hrvatske etničke zajednice

- (in Croatian) Proslava 250. obljetnice doseljavanja veće skupine Bunjevaca (1686.-1936.)

- (in Croatian) Tko su Šokci?

External links

- (in Croatian) Hrvatska riječ weekley

- (in Croatian) Zajednica protjeranih Hrvata iz Srijema Bačke i Banata

- (in Croatian) Hrvati Vojvodine: Josipoviću i Tadiću, zaštitite nas! Otvoreno pismo. Published 17 Feb 2011 by Večernji list.

.png)