Allophone

In phonology, an allophone (/ˈæləfoʊn/; from the Greek ἄλλος, állos, "other" and φωνή, phōnē, "voice, sound") is one of a set of multiple possible spoken sounds, or phones, or signs used to pronounce a single phoneme in a particular language.[1] For example, [t] (as in stop [stɑp]) and [ɾ] (as in Letter [ˈɫɛɾɚ]) are allophones for the phoneme /t/ in English, while these two are considered to be different phonemes in Spanish. On the other hand [d] (as in dolor [do̞ˈlo̞r]) and [ð] (as in nada [ˈnaða]) are allophones for the phoneme /d/ in Spanish, while these two are considered to be different phonemes in English.

The specific allophone selected in a given situation is often predictable from the phonetic context, with such allophones being called positional variants, but some allophones occur in free variation. Replacing a sound by another allophone of the same phoneme usually does not change the meaning of a word, but the result may sound non-native or even unintelligible.

Native speakers of a given language perceive one phoneme in the language as a single distinctive sound and are "both unaware of and even shocked by" the allophone variations that are used to pronounce single phonemes.[2][3]

History of concept

The term "allophone" was coined by Benjamin Lee Whorf in the 1940s. In doing so, he placed a cornerstone in consolidating early phoneme theory.[4] The term was popularized by George L. Trager and Bernard Bloch in a 1941 paper on English phonology[5] and went on to become part of standard usage within the American structuralist tradition.[6]

Complementary and free-variant allophones and assimilation

Whenever a user's speech is vocalized for a given phoneme, it is slightly different from other utterances, even for the same speaker. That has led to some debate over how real and how universal phonemes really are (see phoneme for details). Only some of the variation is significant, by being detectable or perceivable, to speakers.

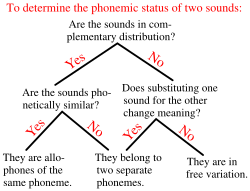

There are two types of allophones, based on whether a phoneme must be pronounced using a specific allophone in a specific situation or whether the speaker has the unconscious freedom to choose the allophone that is used.

If a specific allophone from a set of allophones that correspond to a phoneme must be selected in a given context, and using a different allophone for a phoneme would cause confusion or make the speaker sound non-native, the allophones are said to be complementary. The allophones then complement each other, and one of them is not used in a situation in which the usage of another is standard. For complementary allophones, each allophone is used in a specific phonetic context and may be involved in a phonological process.[7]

In other cases, the speaker can freely select from free variant allophones on personal habit or preference.

Another example of an allophone is assimilation, in which a phoneme is to sound more like another phoneme. One example of assimilation is consonant voicing and devoicing, in which voiceless consonants are voiced before and after voiced consonants, and voiced consonants are devoiced before and after voiceless consonants.

Allotone

An allotone is a term that is sometimes used for a tonic allophone, such as the neutral tone in Standard Mandarin.

Examples

English

There are many allophonic processes in English: lack of plosion, nasal plosion, partial devoicing of sonorants, complete devoicing of sonorants, partial devoicing of obstruents, lengthening and shortening vowels, and retraction.

- Aspiration: In English, a voiceless plosive /p, t, k/ is aspirated (has a string explosion of breath) if it is at the beginning of the first or a stressed syllable in a word. For example, [pʰ] as in pin and [p] as in spin are allophones for the phoneme /p/ because they cannot distinguish words (in fact, they occur in complementary distribution). English-speakers treat them as the same sound, but they are different: the first is aspirated and the second is unaspirated (plain). Many languages treat the two phones differently.

- Nasal plosion – In English, a plosive (/p, t, k, b, d, ɡ/) has nasal plosion if it is followed by a nasal, whether within a word or across a word boundary.

- Partial devoicing of sonorants: In English, sonorants (/j, w, l, r, m, n, ŋ/) are partially devoiced after a voiceless sound in the same syllable.

- Complete devoicing of sonorants: In English, a sonorant is completely devoiced after an aspirated plosive (/p, t, k/).

- Partial devoicing of obstruents: In English, a voiced obstruent is partially devoiced next to a pause or next to a voiceless sound within a word or across a word boundary.

- Retraction: In English, /t, d, n, l/ are retracted before /r/.

Because the choice among allophones is seldom under conscious control, few people realize their existence. English-speakers may be unaware of the differences among six allophones of the phoneme /t/: unreleased [ t̚] as in cat, aspirated [tʰ] as in top, glottalized [ʔ] as in button, flapped [ɾ] as in American English water, nasalized flapped as in winter, and none of the above [t] as in stop. However, they may become aware of the differences if, for example, they contrast the pronunciations of the following words:

- Night rate: unreleased [ˈnʌɪt̚.ɹʷeɪt̚] (without a word space between . and ɹ)

- Nitrate: aspirated [ˈnaɪ.tʰɹ̥eɪt̚] or retracted [ˈnaɪ.tʃɹʷeɪt̚]

A flame that is held before the lips while those words are spoken flickers more for the aspirated nitrate than for the unaspirated night rate. The difference can also be felt by holding the hand in front of the lips. For a Mandarin-speaker, for whom /t/ and /tʰ/ are separate phonemes, the English distinction is much more obvious than for an English-speaker, who has learned since childhood to ignore the distinction.

Allophones of English /l/ may be noticed if the 'light' [l] of leaf [ˈliːf] is contrasted with the 'dark' [ɫ] of feel [ˈfiːɫ]. Again, the difference is much more obvious to a Turkish-speaker, for whom /l/ and /ɫ/ are separate phonemes, than to an English speaker, for whom they are allophones of a single phoneme.

Other languages

There are many examples for allophones in languages other than English. Typically, languages with a small phoneme inventory allow for quite a lot of allophonic variation: examples are Hawaiian and Toki Pona. Here are some examples (the links of language names go to the specific article or subsection on the phenomenon):

- Consonant allophones

- Final devoicing particularly final-obstruent devoicing: Arapaho, English, Nahuatl, and many others

- Voicing of initial letter

- Anticipatory assimilation

- Aspiration changes: Algonquin

- Frication between vowels: Dahalo

- Lenition: Manx

- Voicing of clicks: Dahalo

- Allophones for /b/: Arapaho, Xavante

- Allophones for /d/: Xavante

- Allophones for /f/: Bengali

- Allophones for /j/: Xavante

- Allophones for /k/: Manam

- Allophones for /pʰ/: Garhwali

- [g] and [q] as allophones: a number of Arabic dialects

- [l] and [n] as allophones: Some dialects of Hawaiian

- Allophones for /n/

- [ŋ]: Finnish and many more.

- wide range of variation in Japanese (as archiphoneme /N/)

- Allophones for /r/: Xavante

- Allophones for /ɽ/: Bengali

- Allophones for /s/: Bengali, Taos

- [t] and [k] as allophones: Hawaiian

- Allophones for /w/:

- [v] and [w]: Hindustani, Hawaiian

- fricative [β] before unrounded vowels: O'odham

- Allophones for /z/: Bengali

- Vowel allophones

- [e] and [o] are allophones of /i/ and /u/ in closed final syllables in Malay and [ɪ] and [ʊ] are allophones of /i/ and /u/ in Indonesian.

- [ʉ, ʊ, o̞, o] as allophones for short /u/, and [ɨ, ɪ, e̞, e] as allophones for short /i/ in various Arabic dialects (long /uː/, /oː/, /iː/, /eː/ are separate phonemes in most Arabic dialects).

- Polish

- Russian

- Allophones for /i/, /a/ and /u/: Nuxálk

- Vowel/consonant allophones

- Vowels become glides in diphthongs: Manam

Representing a phoneme with an allophone

Since phonemes are abstractions of speech sounds, not the sounds themselves, they have no direct phonetic transcription. When they are realized without much allophonic variation, a simple broad transcription is used. However, when there are complementary allophones of a phoneme, the allophony becomes significant and things then become more complicated. Often, if only one of the allophones is simple to transcribe, in the sense of not requiring diacritics, that representation is chosen for the phoneme.

However, there may be several such allophones, or the linguist may prefer greater precision than that allows. In such cases, a common convention is to use the "elsewhere condition" to decide the allophone that stands for the phoneme. The "elsewhere" allophone is the one that remains once the conditions for the others are described by phonological rules.

For example, English has both oral and nasal allophones of its vowels. The pattern is that vowels are nasal only before a nasal consonant in the same syllable; elsewhere, they are oral. Therefore, by the "elsewhere" convention, the oral allophones are considered basic, and nasal vowels in English are considered to be allophones of oral phonemes.

In other cases, an allophone may be chosen to represent its phoneme because it is more common in the languages of the world than the other allophones, because it reflects the historical origin of the phoneme, or because it gives a more balanced look to a chart of the phonemic inventory.

An alternative, which is commonly used for archiphonemes, is to use a capital letter, such as /N/ for [m], [n], [ŋ].

In rare cases, a linguist may represent phonemes with abstract symbols, such as dingbats, to avoid privileging any particular allophone.

See also

References

- ↑ R. Jakobson, Structure of Language and Its Mathematical Aspects: Proceedings of symposia in applied mathematics, AMS Bookstore, 1980, ISBN 978-0-8218-1312-6,

...An allophone is the set of phones contained in the intersection of a maximal set of phonetically similar phones and a primary phonetically related set of phones....

- ↑ B.D. Sharma, Linguistics and Phonetics, Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., 2005, ISBN 978-81-261-2120-5,

... The ordinary native speaker is, in fact, often unaware of the allophonic variations of his phonemes ...

- ↑ Y. Tobin, Phonology as human behavior: theoretical implications and clinical applications, Duke University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8223-1822-4,

...always found that native speakers are clearly aware of the phonemes of their language but are both unaware of and even shocked by the plethora of allophones and the minutiae needed to distinguish between them....

- ↑ Lee, Penny (1996). The Whorf Theory Complex — A Critical Reconstruction. John Benjamins. pp. 46, 88.

- ↑ Trager, George L. (1959). "The Systematization of the Whorf Hypothesis". Anthropological Linguistics. Operational Models in Synchronic Linguistics: A Symposium Presented at the 1958 Meetings of the American Anthropological Association. 1 (1): 31–35. JSTOR 30022173.

- ↑ Hymes, Dell H.; Fought, John G. (1981). American Structuralism. Walter de Gruyter. p. 99.

- ↑ Barbara M. Birch, English L2 reading: getting to the bottom, Psychology Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-8058-3899-2,

...When the occurrence of one allophone is predictable when compared to the other, as in this case, we call this complementary distribution. Complementary distribution means that the allophones are 'distributed' as complements....