Rockville, Maryland

| Rockville, Maryland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||||

| The Mayor and Council of Rockville[1] | |||||

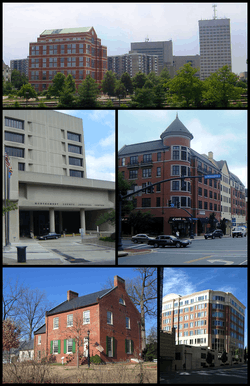

Downtown Rockville in 2001, the Montgomery County Judicial Center in 2010, the Rockville Town Square in 2010, the Beall-Dawson House in 2005, and downtown Rockville in 2008. | |||||

| |||||

| Motto(s): "Get Into It!"[2] | |||||

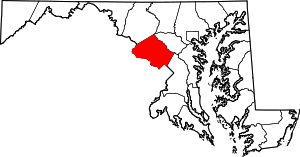

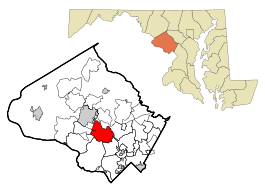

Location in Montgomery County and the U.S. state of Maryland | |||||

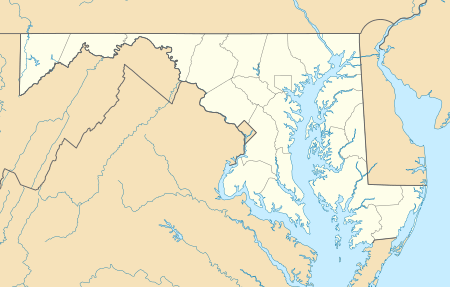

Rockville Location within the U.S. state of Maryland  Rockville Rockville (the US) | |||||

| Coordinates: 39°5′1″N 77°8′54″W / 39.08361°N 77.14833°WCoordinates: 39°5′1″N 77°8′54″W / 39.08361°N 77.14833°W | |||||

| Country |

| ||||

| State |

| ||||

| County |

| ||||

| Settled | 1717 | ||||

| Founded | 1803 | ||||

| Incorporated | 1860 | ||||

| Government | |||||

| • Mayor | Bridget Donnell Newton (I)[3] | ||||

| Area[4] | |||||

| • City | 13.57 sq mi (35.15 km2) | ||||

| • Land | 13.51 sq mi (34.99 km2) | ||||

| • Water | 0.06 sq mi (0.16 km2) | ||||

| Elevation | 451 ft (137 m) | ||||

| Population (2010)[5] | |||||

| • City | 61,209 | ||||

| • Estimate (2017)[6] | 68,401 | ||||

| • Density | 4,500/sq mi (1,700/km2) | ||||

| • Metro | 5,306,565 | ||||

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) | ||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | ||||

| ZIP code | 20847-53 & 20857 | ||||

| Area code(s) | 301, 240 | ||||

| FIPS code | 24-67675 | ||||

| GNIS feature ID | 0586901 | ||||

| Website | www.RockvilleMD.gov | ||||

Rockville is a city and the county seat of Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, part of the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area. The 2010 census tabulated Rockville's population at 61,209, making it one of the largest communities in Maryland[7] and the third largest location in Montgomery County, after Silver Spring and Germantown.[8]

Rockville, along with neighboring Gaithersburg and Bethesda, is at the core of the Interstate 270 Technology Corridor which is home to numerous software and biotechnology companies as well as several federal government institutions. The city also has several upscale regional shopping centers and is one of the major retail hubs in Montgomery County.

History

Early history

Situated in the Piedmont region and crossed by three creeks (Rock Creek, Cabin John Creek, and Watts Branch), Rockville provided an excellent refuge for semi-nomadic Native Americans as early as 8000 BC. By the first millennium BC, a few of these groups had settled down into year-round agricultural communities that exploited the native flora, including sunflowers and marsh elder. By AD 1200, these early groups (dubbed Montgomery Indians by later archaeologists) were increasingly drawn into conflict with the Senecas and Susquehannocks who had migrated south from Pennsylvania and New York. Within the present-day boundaries of the city, six prehistoric sites have been uncovered and documented, along with numerous artifacts several thousand years old. By the year 1700, under pressure from European colonists, the majority of these original inhabitants had been driven away.

The indigenous population carved a path on the high ground, known as Sinequa Trail, which is now downtown Rockville. Later, the Maryland Assembly set the standard of 20 feet for main thoroughfares and designated the Rock Creek Main Road or Great Road to be built to this standard. In the mid-18th century, Lawrence Owen opened a small inn on the road. The place, known as Owen's Ordinary, took on greater prominence when, on April 14, 1755, Major General Edward Braddock stopped at Owen's Ordinary on a start of a mission from George Town (now Washington, D.C.) to press British claims of the western frontier. The location of the road, near the present Rockville Pike, was strategically located on higher ground making it dry year-round.[9]:6–9

18th century

The first land patents in the Rockville area were obtained by Arthur Nelson between 1717 and 1735. Within three decades, the first permanent buildings in what would become the center of Rockville were established on this land. Still a part of Prince George's County at this time, the growth of Daniel Dulaney's Frederick Town prompted the separation of the western portion of the county, including Rockville, into Frederick County in 1748.

Being a small, unincorporated town, early Rockville was known by a variety of names, including Owen's Ordinary, Hungerford's Tavern, and Daley's Tavern. The first recorded mention of the settlement which would later become known as Rockville dates to the Braddock Expedition in 1755. On April 14, one of the approximately two thousand men who were accompanying General Braddock through wrote the following: "we marched to larance Owings or Owings Oardianary, a Single House, it being 18 miles and very dirty." Owen's Ordinary was a small rest stop on Rock Creek Main Road (later the Rockville Pike), which stretched from George Town to Frederick Town, and was then one of the largest thoroughfares in the colony of Maryland.

On September 6, 1776,[10] the Maryland Constitutional Convention agreed to a proposal introduced by Thomas Sprigg Wootton wherein Frederick County, the largest and most populous county in Maryland, would be divided into three smaller units. The southern portion of the county, of which Rockville was a part, was named Montgomery County. The most populous and prosperous urban center in this new county was George Town, but its location at the far southern edge rendered it worthless as a seat of local government. Rockville, a small, but centrally located and well-traveled town, was chosen as the seat of the county's government. At the time, Rockville did not have a name; it was generally called Hungerford's Tavern, after the well-known tavern in it.[10] After being named the county seat, the village was referred to by all as Montgomery Court House.[10] The tavern served as the county courthouse, and it held its first such proceedings on May 20, 1777.[10]

In 1784, William Prather Williams, a local landowner, hired a surveyor to lay out much of the town.[10] In his honor, many took to calling the town Williamsburg.[10] In practice, however, Williamsburg and Montgomery Court House were used interchangeably. Rockville came to greater prominence when Montgomery county was created and later when George Town was ceded to the federal government to create the District of Columbia.[9]

19th century

It was first considered to officially name the town Wattsville, after the nearby Watts Branch, but the stream was later considered too small to give its name to the town.[10] On July 16, 1803, when the area was officially entered into the county land records with the name "Rockville," derived from Rock Creek.[10][11] Nevertheless, the name Montgomery Court House continued to appear on maps and other documents through the 1820s.

In November 1833, guests of the Old Hungerford Tavern were playing cards in the card room when they saw the Leonids meteor shower above.[12] The guests through their cards in the fire and knelt in prayer to ask for God's forgiveness.[12]

By petition of Rockville's citizens, the Maryland General Assembly incorporated the village on March 10, 1860. During the American Civil War, General George B. McClellan stayed at the Beall Dawson house in 1862. In addition, General J.E.B. Stuart and an army of 8,000 Confederate cavalrymen marched through and occupied Rockville on June 28, 1863,[13] while on their way to Gettysburg and stayed at the Prettyman house. Jubal Anderson Early had also crossed through Maryland on his way to and from his attack on Washington. In 1913, on the birthday of Jefferson Davis, the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a statue near the Rockville courthouse dedicated to Confederate soldiers from Montgomery County.[14][15] The monument was removed in 2017 as part of a wave of removals of Confederate monuments and memorials in response to the 2015 Charleston church shooting, and is now located in White's Ferry.[16]

In 1873, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad arrived, making Rockville easily accessible from Washington, D.C. (See Metropolitan Branch.) In July 1891, the Tennallytown and Rockville Railway inaugurated Rockville's first trolley service connecting to the Georgetown and Tennallytown Railway terminus at Western Avenue and Wisconsin Avenue.

Twentieth century through today

The newly opened railroad provided service from Georgetown to Rockville, connecting Rockville to Washington, D.C. by trolley. Trolley service operated for four decades, until, eclipsed by the growing popularity of the automobile, service was halted in August 1935. The Blue Ridge Transportation Company provided bus service for Rockville and Montgomery County from 1924 through 1955. After 1955, Rockville would not see a concerted effort to develop a public transportation infrastructure until the 1970s, when the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) began work to extend the Washington Metro into Rockville and extended Metrobus service into Montgomery County. The Rockville station of Washington Metro began service on July 25, 1984, and the Twinbrook station began service on December 15, 1984. Metrobus service was supplemented by Montgomery County's own Ride On bus service starting in 1979. MARC, Maryland's Rail Commuter service, serves Rockville with its Brunswick line. From Rockville MARC provides service to Union Station in Washington D.C. (southbound) and, Frederick and Martinsburg, West Virginia (northbound), as well as intermediate points. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service from Rockville to Chicago and Washington D.C.

The mid-20th century saw substantial growth in Rockville, especially with the annexation of the Twinbrook subdivision in 1949, which added hundreds of new homes and thousands of new residents to the city. In 1954, Congressional Airport closed, and its land was sold to developers to build residences and a commercial shopping center.[17] The shopping center, named Congressional Plaza, opened in 1958.[18] These new areas provided affordable housing and grew quickly with young families eager to start their lives following World War II.

During the Cold War, it was considered safer to remain in Rockville than to evacuate during a hypothetical nuclear attack on Washington, D.C. Bomb shelters were built, including the largest one at Glenview Mansion and 15 other locations. The I-270 highway was designated as an emergency aircraft landing strip. Two Nike missile launcher sites were located on Muddy Branch and Snouffer School Roads until the mid-1970s.[9]:163

From the 1960s, Rockville's town center, formerly one of the area's commercial centers, suffered from a period of decline. Rockville soon became the first city in Maryland to enter into a government funded urban renewal program. This resulted in the demolition of most of the original business district. Included in the plan was the unsuccessful Rockville Mall, which failed to attract either major retailers or customers and was demolished in 1994, various government buildings such as the new Montgomery County Judicial Center, and a reorganization of the road plan near the Courthouse. Unfortunately, the once-promising plan was for the most part a disappointment. Although efforts to restore the town center continue, the majority of the city's economic activity has since relocated along Rockville Pike (MD Route 355/Wisconsin Avenue). In 2004, Rockville Mayor Larry Giammo announced plans to renovate the Rockville Town Square, including building new stores and housing and relocating the city's library. In the past year, the new Rockville Town Center has been transformed and includes a number of boutique-like stores, restaurants, condominiums and apartments, as well as stages, fountains and the Rockville Library.[19] The headquarters of the U.S. Public Health Service is on Montrose Road while the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission's headquarters is just south of the City's corporate limits.

The city is closely associated with the neighboring towns of Kensington and the unincorporated census-designated place, North Bethesda. The Music Center at Strathmore, an arts and theater center, opened in February 2005 in the latter of these two areas and is presently the second home of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and the Fitzgerald Theatre in Rockville Civic Center Park has provided diverse entertainment since 1960. In 1998, Regal Cinemas opened in Town Center[9]:217 and the city annexed 900 acres of land.[20]

The city also has a brass band in the British style.

The R.E.M. song "(Don't Go Back To) Rockville", released in 1984, was written by Mike Mills about not wanting his girlfriend Ingrid Schorr to return to Rockville, Maryland.[21]

In 1975, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Fitzgerald's caskets were reinterred at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Rockville, Maryland where his father, Edward, and a number of Key family members had been buried.[22]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.57 square miles (35.15 km2), of which, 13.51 square miles (34.99 km2) is land and 0.06 square miles (0.16 km2) is water.[4]

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Rockville has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[23] According to the United States Department of Agriculture, Rockville is in hardiness zone 7a,[24] meaning that the average annual minimum winter temperature is 0 to 5 °F (−18 to −15 °C).[25] The average first frost occurs on October 21, and the average final frost occurs on April 16.[26]

Demographics

Income

The median income for a household in the city as of 2015 was $100,239.[27] As of 2007, the median income for a family was $98,257. Males have a median income of $53,764 versus $38,788 for females. In 2015, the per capita income for the city was $49,399.[27] 7.8% of the population and 5.6% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 8.9% of those under the age of 18 and 7.9% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line.

2010 census

As of the census[5] of 2010, there were 61,209 people, 23,686 households, and 15,524 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,530.6 inhabitants per square mile (1,749.3/km2). There were 25,199 housing units at an average density of 1,865.2 per square mile (720.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 60.4% White (52.8% non-Hispanic white), 9.6% African American, 0.3% Native American, 20.6% Asian, 5.3% from other races, and 3.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 14.3% of the population.

There were 23,686 households of which 31.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.3% were married couples living together, 9.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.5% were non-families. 27.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.08.

The median age in the city was 38.7 years. 21.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 31.1% were from 25 to 44; 26.3% were from 45 to 64; and 14% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.9% male and 52.1% female.

Economy

Choice Hotels, Westat, and Bethesda Softworks/ZeniMax Media are headquartered in Rockville.

Largest employers

According to the city's 2012 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[28] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Montgomery County | 4,985 |

| 2 | Montgomery County Public Schools | 2,500 |

| 3 | Lockheed Martin Information Systems | 2,000 |

| 4 | Westat | 2,000 |

| 5 | Booz Allen Hamilton | 1,282 |

| 6 | Montgomery College | 955 |

| 7 | Quest Software | 784 |

| 8 | BAE Systems | 650 |

| 9 | City of Rockville | 537 |

| 10 | Adventist HealthCare | 415 |

Sports

- Rockville Express, a Cal Ripken, Sr. Collegiate Baseball League team, 2007 CRSCBL League Champions

Government

Rockville has a council-manager form of government.[29]

Mayor

The current mayor of Rockville is Bridget Donnell Newton.

Rockville was incorporated in 1860, but its early records were destroyed by Confederate soldiers in July 1864.[30]

Rockville's mayors include:[3]

| Name | Tenure | Party | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William V. Bouic[3] | 1888-1890[3] | Democratic | ||

| Daniel F. Owens[3] | 1890[3] | |||

| William V. Bouic[3] | 1890-1891[3] | |||

| Hattersley W. Talbott[3] | 1892-1893[3] | |||

| Jacob Poss[3] | 1893-1894[3] | |||

| John G. England[3] | 1894-1896[3] | |||

| Joseph Reading[3] | 1896-1898[3] | |||

| Spencer C. Jones[3] | 1898-1901[3] | |||

| Hattersley W. Talbott[3] | 1901-1906[3] | |||

| Lee Offutt[3] | 1906-1916[3] | |||

| Willis Burdette[3] | 1916-1918[3] | |||

| Lee Offutt[3] | 1918-1920[3] | |||

| O. M. Linthicum[3] | 1920-1924[3] | |||

| Charles G. Holland[3] | 1924-1926[3] | |||

| J. Roger Spates[3] | 1926-1932[3] | |||

| Douglas Blandford[3] | 1932-1946[3] | |||

| G. LaMar Kelly[3] | 1946-1952[3] | |||

| Daniel Weddle[3] | 1952-1954[3] | |||

| Dickran Y. Hovsepian[3] | 1954-1958[3] | |||

| Alexander J. Greene[3] | 1958-1962[3] | |||

| Frank A. Ecker[3] | 1962-1968[3] | |||

| Achilles M. Tuchtan[3] | 1968-1972[3] | |||

| Matthew J. McCartin[3] | 1972-1974[3] | |||

| William E. Hanna, Jr.[3] | 1974-1982[3] | |||

| John R. Freeland[3] | 1982-1984[3] | |||

| Viola D. Hovesepian[3] | 1984-1985[3] | Appointed mayor[3] | ||

| Steven Van Grack[3] | 1985-1987[3] | Independent[31] | ||

| Douglas M. Duncan[3] | 1987-1993[3] | Democratic[3] | ||

| James Coyle[3] | 1993-1995[3] | |||

| Rose G. Krasnow[3] | 1995-2001[3] | |||

| Larry Giammo[3] | 2001-2007[3] | Independent[32] | ||

| Susan R. Hoffmann[3] | 2007-2009[3] | |||

| Phyllis R. Marcuccio[3] | 2009-2013[3] | Independent[3] | ||

| Bridget Donnell Newton[3] | 2013–present[3] | Independent[3] | ||

Representative body

Rockville has a four-member City Council, whose members, along with the mayor, serve as the governing body of the city. The councilmembers for the 2015 to 2019 term are Beryl L. Feinberg, Virginia Onley, Julie Palakovich Carr, and Mark Pierzchala.

Departments and offices

The city manager oversees the following departments:

Law enforcement

The city is served by the Rockville City Police Department and is aided by the Montgomery County Police Department as directed by authority.[34]

Education

Rockville is served by Montgomery County Public Schools. Public high schools in Rockville include Thomas S. Wootton High School, Richard Montgomery High School, and Rockville High School.

Private schools located in Rockville include the Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School, the Melvin J. Berman Hebrew Academy and the Montrose Christian School.

Institutions of higher education in Rockville include Montgomery College (Rockville Campus), The University of Maryland University College (main campus is in Adelphi, Maryland), The Johns Hopkins University Montgomery County Campus (main campus is in Baltimore, Maryland), and the Universities at Shady Grove, a collaboration of nine Maryland public degree-granting institutions, all have Rockville addresses, but are outside the city limits.

Transportation

The Red Line of the Washington Metro rail system serves the Rockville station and the Twinbrook station. The Rockville station is located at Hungerford Drive near Park Road. The Twinbrook station is located near Rockville Pike and Halpine Road with entrances on Chapman Avenue.

At the same location as the Rockville Metro station is Rockville Station on the Brunswick Line of the MARC commuter rail system, which runs to and from Washington, DC.

Public transportation connects Rockville directly to the regional transit hub at BWI Airport, and to downtown Baltimore via the Maryland Transit Administration ICC Bus and the Baltimore Light Rail.

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides intercity train service to Rockville. The city's passenger rail station is located at 251 Hungerford Drive (at Park Road), ZIP code 20850; this is also the location of the MARC station described above.

- Amtrak Train 29, the westbound Capitol Limited, is scheduled to depart Rockville daily with service to Pittsburgh and overnight service to Chicago.

- Amtrak Train 30, the eastbound Capitol Limited, is scheduled to depart Rockville at 12:30pm on its return to Washington Union Station.

Sister cities

Rockville has one sister city:

It has a "friendship relationship" (a step preliminary to a sister-city relationship) with another city:

Notable people

- Jamshid Amouzegar, former Prime Minister of Iran[37]

- Gordy Coleman, Major League Baseball player for Cleveland Indians and Cincinnati Reds

- Jerome Dyson (born 1987), basketball player for Hapoel Jerusalem of Israeli Premier League[38]

- Paul Goldstein (born 1976), tennis player

- Spike Jonze, film director[39]

- Helen Maroulis, Olympic wrestler[40]

- Rachel Parsons, figure skater, 2017 junior national champion[41]

- Josh Tillman ("Father John Misty"), musician

- Sir Robert Bryson Hall II ("Logic"), rapper

- BT, musician

See also

- List of famous people from the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area

- Tower Oaks - a planned community in Rockville

References

- ↑ "Section 1. - City Incorporated; General Powers". Rockville City Code: General Ordinances of the City. Rockville, Maryland: The Mayor and Council of Rockville. February 26, 1990. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

The inhabitants of the City of Rockville, Montgomery County, are a body corporate by the name of 'The Mayor and Council of Rockville,' and by that name may have perpetual succession, sue and be sued, and have and use a common seal. (Res. No. 8-78; Res. No. 24-60)

- ↑ "City of Rockville, Maryland". City of Rockville, Maryland. Archived from the original on June 17, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 State of Maryland (February 25, 2013). "Rockville Mayors, Montgomery County, Maryland". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ↑ US Census Bureau (July 2012). "Maryland: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). 2010 Census of Population and Housing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-19.

- ↑ "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Maryland's 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting - 2010 Census". Census.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- 1 2 3 4 McGuckian, Eileen S. (2001). Rockville: Portrait of a City. Franklin, Tennessee: Hillsboro Press. ISBN 1-57736-235-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Proctor, John Clagett (May 20, 1934). "Rockville Among Old Maryland Towns". Washington Evening Star. p. 76.

- ↑ "Profile for Rockville Maryland, MD". ePodunk. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- 1 2 Maryland Writer's Project, Works Project Administration. Maryland: A Guide to the Old Line State. Oxford University Press. August 1940. p. 512.

- ↑ "Capture of a Wagon Train: One Hundred and Seventy-eight Wagons and Over One Thousand Mules Gobbled Up: The Rebels in Possession of Rockville". Washington Evening Star. June 29, 1863. p. 2.

- ↑ "The Confederate Monument, a War Memorial". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ↑ Mark Walston (July 21, 2017). "Looking Back at the Creation of the County's Confederate Memorials". Bethesda Beat.

- ↑ Bill Turque (July 24, 2017). "Confederate statue moved from Rockville courthouse over the weekend". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Congressional Airport Sold For Dwellings". The Washington Post. April 4, 1954. p. M6.

- ↑ Goodman, S. Oliver (May 1, 1958). "New Rockville Shop Center Is Dedicated". The Washington Post. p. C14.

- ↑ Archived June 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Rockville City Police Department". 2 September 1999. Archived from the original on 2 September 1999.

- ↑ Black, Johnny (2004). Reveal: The Story of R.E.M. Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-776-5.

- ↑ "Scott and Zelda: Fractious in life, but together in death in a Rockville cemetery plot". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ "Rockville, Maryland Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- ↑ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zones: Maryland & District of Columbia". Agricultural Research Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ↑ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". Agricultural Research Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Freeze / Frost Occurrence Data" (PDF). National Climatic Data Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- 1 2 "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts selected: Rockville city, Maryland". www.census.gov.

- ↑ "City of Rockville CAFR". p. 104. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ↑ "FAQ - Council-Manager Form of Government". City of Rockville. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ↑ "Rockville Mayors, Montgomery County, Maryland". Maryland State Archives. November 18, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ↑ Kaiman, Beth. "Rockville Fund Raising Uneven". The Washington Post. October 8, 1987. p. MDB12.

- ↑ Wagner, John; Craig, Tim. "Duncan Rebukes O'Malley Over Crime: Mayor Accused of Distorting Baltimore Statistics to Create a Rosier Picture". The Washington Post. February 14, 2006. p. B1.

- ↑ "Rockville City Government Organization". City of Rockville. Archived from the original on 2007-07-27. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ↑ "Rockville, MD - Official Website - Police". Rockvillemd.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ "RSCC-HomePage". Rocknet.org. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ Contessa Crisostomo (2008-12-24). "Rockville to welcome another Sister City: Jiaxing, China". Gazette.net. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ Matt Schudel (19 October 2016). "Jamshid Amouzegar, former Iranian prime minister, dies at 93". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Jerome Dyson basketball-reference.com profile". basketball-reference.com. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ↑ Keane, Katharine (April 20, 2015). "15 Celebrities Who Grew Up Here". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Athlete Bio: Helen Maroulis". TeamUSA.org. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Competition Results: Rachel PARSONS / Michael PARSONS". International Skating Union.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rockville, Maryland. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Rockville. |

- Official website

- The Washington Post's Guide to Rockville

- City of Rockville at the Wayback Machine (archived February 19, 1998)

- City of Rockville at the Wayback Machine (archived November 14, 1996)

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baltimore  Columbia |

1 | Baltimore | Independent city | 620,961 | Germantown .jpg) Silver Spring | ||||

| 2 | Columbia | Howard | 99,615 | ||||||

| 3 | Germantown | Montgomery | 86,395 | ||||||

| 4 | Silver Spring | Montgomery | 71,452 | ||||||

| 5 | Waldorf | Charles | 67,752 | ||||||

| 6 | Glen Burnie | Anne Arundel | 67,639 | ||||||

| 7 | Ellicott City | Howard | 65,834 | ||||||

| 8 | Frederick | Frederick | 65,239 | ||||||

| 9 | Dundalk | Baltimore | 63,597 | ||||||

| 10 | Rockville | Montgomery | 61,209 | ||||||

.png)